Effects of Salinity on the Growth, Biochemical Components, and Epiphytic Bacterial Community of Desmodesmus intermedius

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultivation of D. intermedius and Salinity Experiments

2.2. Determination of Chlorophyll a Content and Protein Content

2.3. Determination of Total Carbohydrate Content and Total Lipid Content

2.4. Sample Processing and Sequencing for Microbial Diversity Analysis

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Variations in D. intermedius Cell Density, Chlorophyll a, Protein, Total Carbohydrate, and Total Lipid Under Different Salinity Conditions

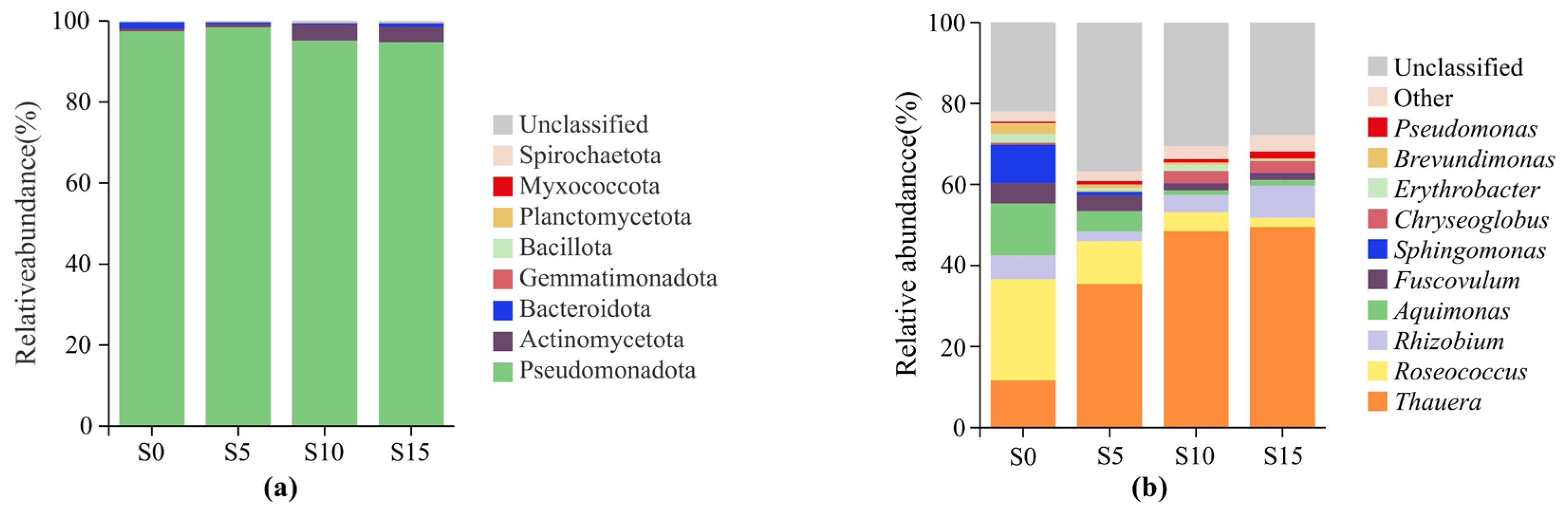

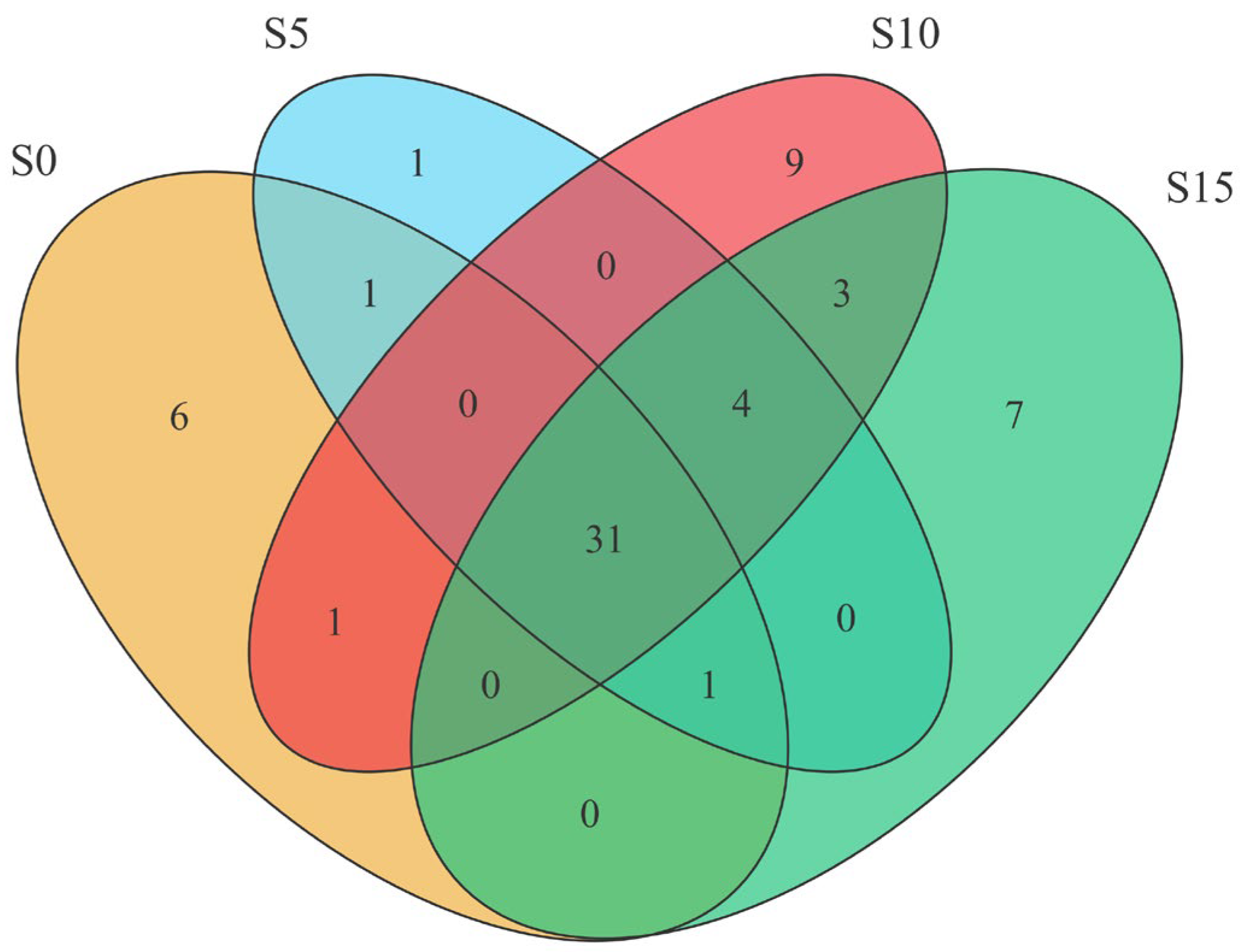

3.2. ASV Analysis and Taxonomic Composition Profiling of Epiphytic Bacterial Communities Associated with D. intermedius

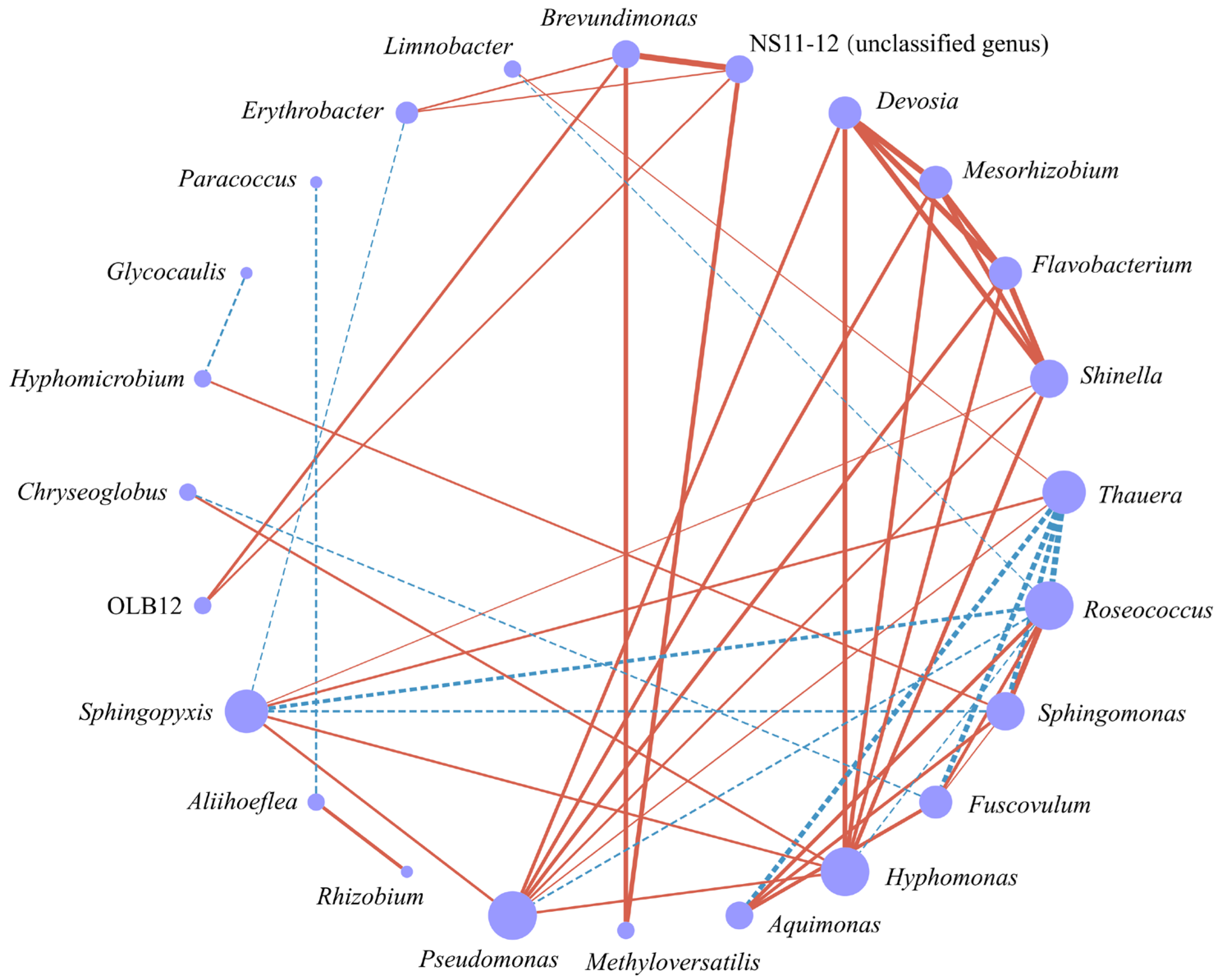

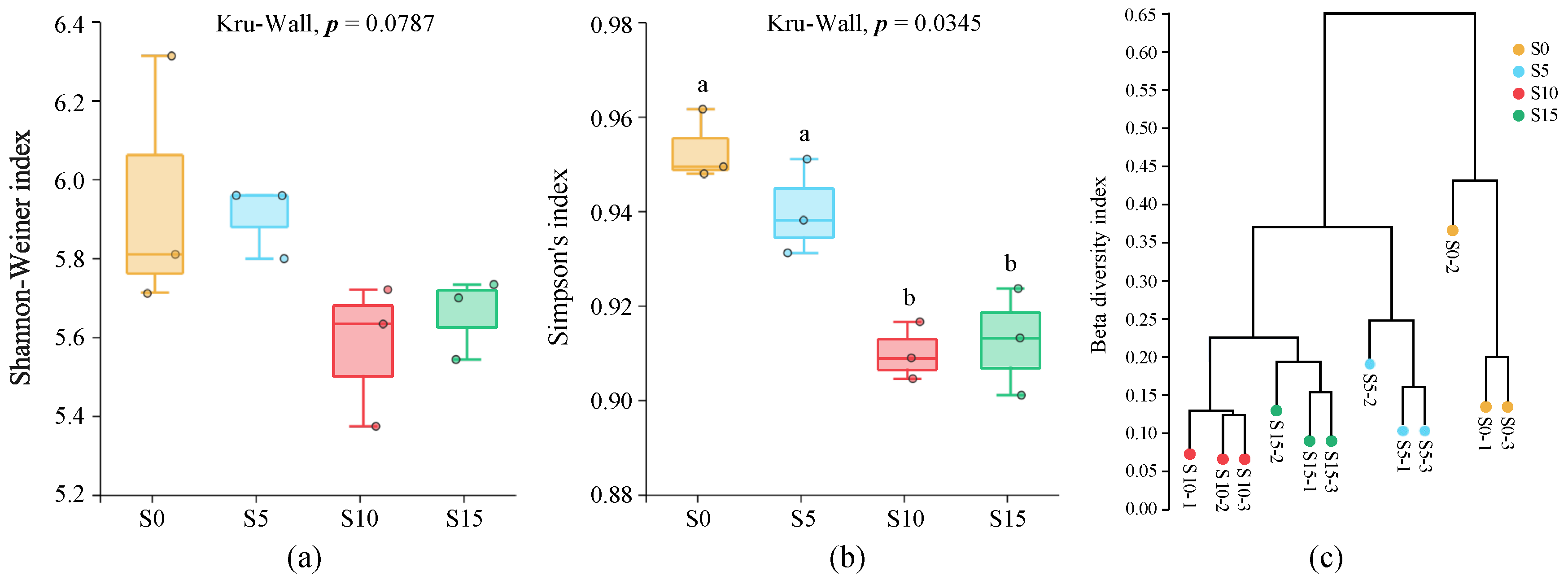

3.3. Genus Diversity Analysis of the Epiphytic Bacterial Community in D. intermedius

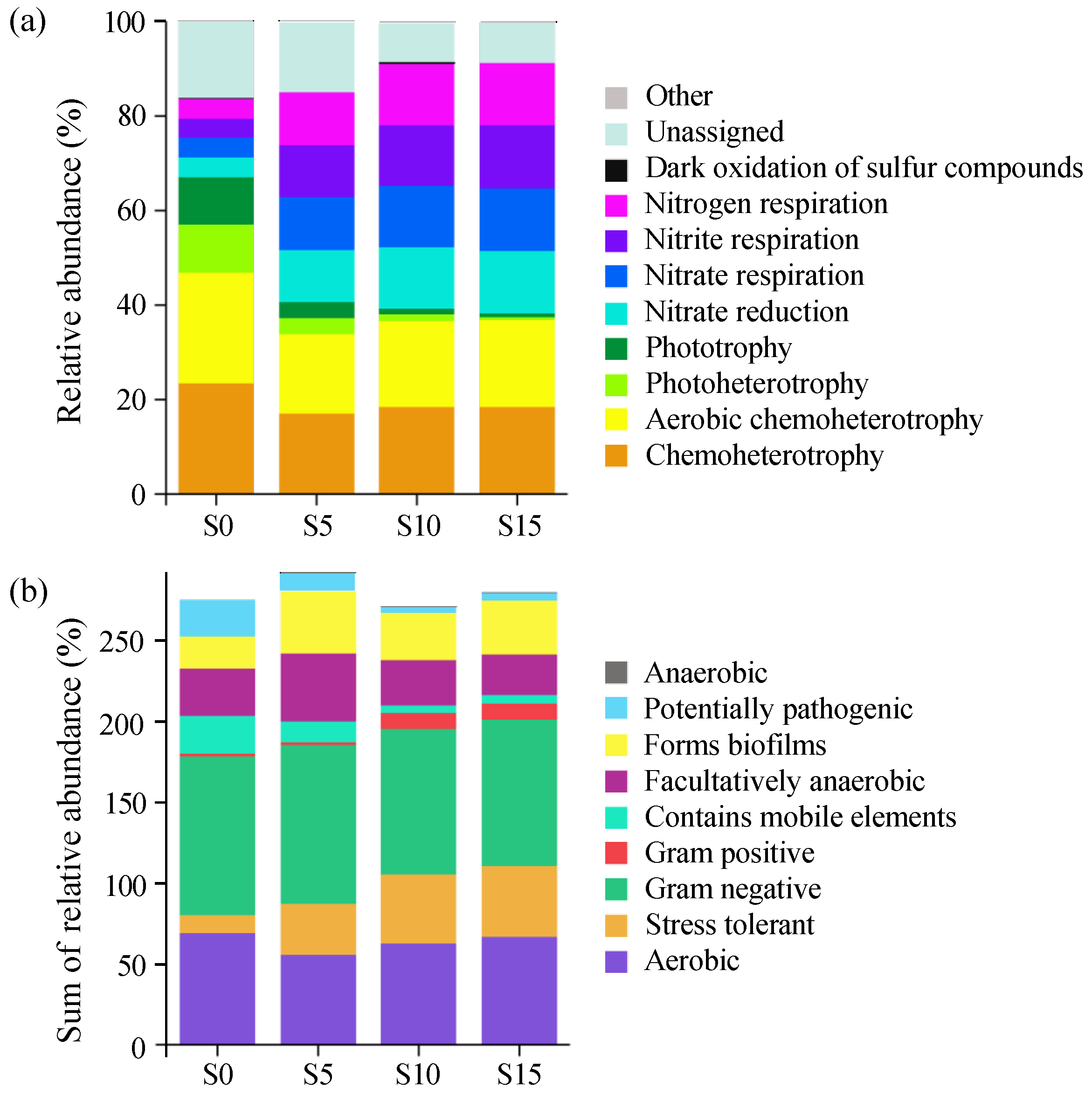

3.4. Functional Prediction Analysis of the Epiphytic Bacterial Community in D. intermedius

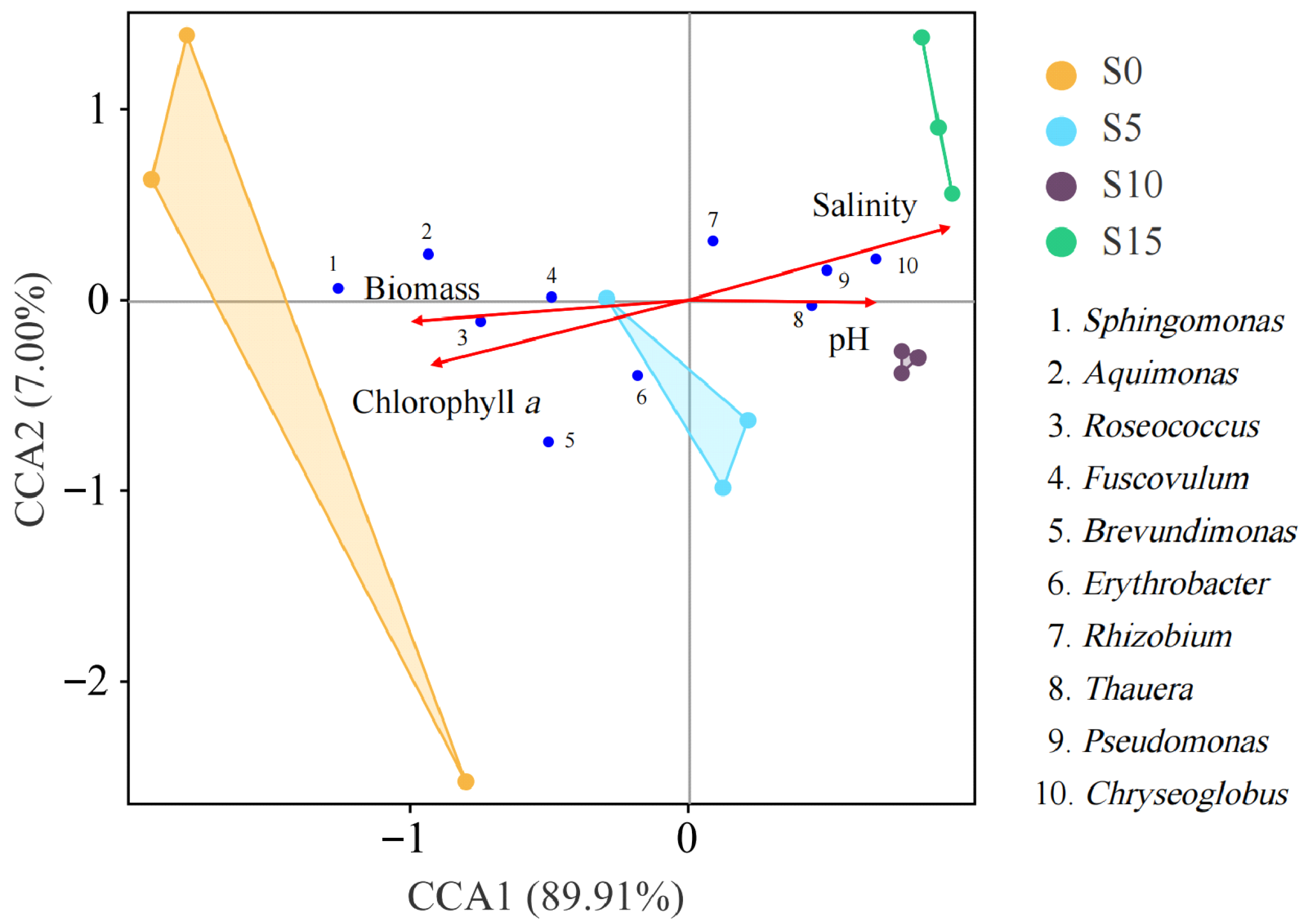

3.5. Environmental Factor Analysis of the Epiphytic Bacterial Community in D. intermedius

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Salinity on Growth and Biochemical Composition

4.2. Effects of Salinity on Diversity, Abundance, and Function of Epiphytic Bacteria

4.3. Relationships Between Epiphytic Bacterial Communities and Environmental Factors

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bell, W.; Mitchell, R. Chemotactic and Growth Responses of Marine Bacteria to Algal Extracellular Products. Biol. Bull. 1972, 143, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yu, S.; Yu, Z.; Ma, M.; Liu, M.; Pei, H. Phycoremediation Potential of Salt-Tolerant Microalgal Species: Motion, Metabolic Characteristics, and Their Application for Saline–Alkali Soil Improvement in Eco-Farms. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafana, A. Characterization and Optimization of Production of Exopolysaccharide from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 95, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, Z.; Miao, X. Lipid Droplets Mediate Salt Stress Tolerance in Parachlorella kessleric. Plant Physiol. 2019, 181, 510–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamoto, K.; Shiraiwa, Y. Salt-Regulated Mannitol Metabolism in Algae. Mar. Biotechnol. 2005, 7, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oslan, S.N.H.; Shoparwe, N.F.; Yusoff, A.H.; Rahim, A.A.; Chang, C.S.; Tan, J.S.; Oslan, S.N.; Arumugam, K.; Ariff, A.B.; Sulaiman, A.Z.; et al. A Review on Haematococcus pluvialis Bioprocess Optimization of Green and Red Stage Culture Conditions for the Production of Natural Astaxanthin. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ge, H.; Liu, T.; Tian, X.; Wang, Z.; Guo, M.; Chu, J.; Zhuang, Y. Salt Stress Induced Lipid Accumulation in Heterotrophic Culture Cells of Chlorella protothecoides: Mechanisms Based on the Multi-Level Analysis of Oxidative Response, Key Enzyme Activity and Biochemical Alteration. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 228, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Peng, S.; Li, Q.; Wei, S.; Zhang, Q.; An, X.; Li, H. Exploration of Two-Stage Cultivation Strategy Using Nitrogen Limited and Phosphorus Sufficient to Simultaneously Improve the Biomass and Lipid Productivity in Desmodesmus intermedius Z8. Fuel 2023, 338, 127306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Peng, S.; Zhang, Q.; Long, H.; Li, H. Enhancement of Lipid Production in Desmodesmus intermedius Z8 by Ultrasonic Stimulation Coupled with Nitrogen and Phosphorus Stress. Biochem. Eng. J. 2021, 172, 108061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samo, T.J.; Rolison, K.A.; Swink, C.J.; Kimbrel, J.A.; Yilmaz, S.; Mayali, X. The Algal Microbiome Protects Desmodesmus intermedius from High Light and Temperature Stress. Algal Res. 2023, 75, 103245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yue, Z.; Wen, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M. Strong Inhibitory Effects of Desmodesmus sp. on Microcystis Blooms: Potential as a Biological Control Agent in Aquaculture. Aquac. Rep. 2025, 40, 102579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Alwathnani, H.A.; Usman, M.; Mohamed, B.A.; Abomohra, A.E.-F.; Salama, E.-S. Cultivation of Freshwater Microalgae in Wastewater under High Salinity for Biomass, Nutrients Removal, and Fatty Acids/Biodiesel Production. Waste Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 3245–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanier, R.Y.; Kunisawa, R.; Mandel, M.; Cohen-Bazire, G. Purification and Properties of Unicellular Blue-Green Algae (Order Chroococcales). Bacteriol. Rev. 1971, 35, 171–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.-B.; Zhu, Y.-R.; Wang, W.-J.; Bai, Y.-L.; Wang, Y. Cell Line Screening of Catharanthus roseus for High Yield Production of Ajmalicine. J. Med. Plants Res. 2011, 3, 420–424. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, V.; Karibasappa, G.; Dodamani, A.; Mali, G. Estimating the Carbohydrate Content of Various Forms of Tobacco by Phenol-Sulfuric Acid Method. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2017, 6, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izard, J.; Limberger, R.J. Rapid Screening Method for Quantitation of Bacterial Cell Lipids from Whole Cells. J. Microbiol. Methods 2003, 55, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpy, F.; Lucas, Y.; Merdy, P. Evaluation of Roundup® Effects on Chlorella vulgaris through Spectral Changes in Photosynthetic Pigments in Fresh and Marine Water. Environ. Adv. 2022, 8, 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Li, D.; Tian, X.; Huang, G.; He, M.; Wang, C.; Kumbhar, A.N.; Woldemicael, A.G. Mitigating Salinity Stress through Interactions between Microalgae and Different Forms (Free-Living & Alginate Gel-Encapsulated) of Bacteria Isolated from Estuarine Environments. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chokshi, K.; Pancha, I.; Ghosh, A.; Mishra, S. Salinity Induced Oxidative Stress Alters the Physiological Responses and Improves the Biofuel Potential of Green Microalgae Acutodesmus dimorphus. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244, 1376–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, P.; Yan, D.; Sun, R.; Song, X.; Lin, T.; Yi, Y. Community Composition and Correlations between Bacteria and Algae within Epiphytic Biofilms on Submerged Macrophytes in a Plateau Lake, Southwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 727, 138398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florez, J.Z.; Camus, C.; Hengst, M.B.; Buschmann, A.H. A Functional Perspective Analysis of Macroalgae and Epiphytic Bacterial Community Interaction. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Wijffels, R.H.; Smidt, H.; Sipkema, D. The Effect of the Algal Microbiome on Industrial Production of Microalgae. Microb. Biotechnol. 2018, 11, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Camejo, J.; Barat, R.; Pachés, M.; Murgui, M.; Seco, A.; Ferrer, J. Wastewater Nutrient Removal in a Mixed Microalgae–Bacteria Culture: Effect of Light and Temperature on the Microalgae–Bacteria Competition. Environ. Technol. 2018, 39, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tec-Campos, D.; Tibocha-Bonilla, J.D.; Jiang, C.; Passi, A.; Thiruppathy, D.; Zuñiga, C.; Posadas, C.; Zepeda, A.; Zengler, K. A Genome-Scale Metabolic Model for the Denitrifying Bacterium Thauera sp. MZ1T Accurately Predicts Degradation of Pollutants and Production of Polymers. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2025, 21, e1012736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voolstra, C.R.; Ziegler, M. Adapting with Microbial Help: Microbiome Flexibility Facilitates Rapid Responses to Environmental Change. BioEssays 2020, 42, 2000004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Garcia, L.; Gariépy, Y.; Barnabé, S.; Raghavan, G.S.V. Effect of Environmental Factors on the Biomass and Lipid Production of Microalgae Grown in Wastewaters. Algal Res. 2019, 41, 101521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, S.; Lu, Y.; Sun, K.; Jia, J.; Wang, Y. Phytoplankton Community Response to Nutrients along Lake Salinity and Altitude Gradients on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 128, 107848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Xiong, J.; Wang, X.C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhou, B.; Pan, P.; Liu, Y.; Ding, F. Relationship between Phytoplankton Community and Environmental Factors in Landscape Water with High Salinity in a Coastal City of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 28460–28470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Bai, J.; Tebbe, C.C.; Zhao, Q.; Jia, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Yu, L. Salinity Controls Soil Microbial Community Structure and Function in Coastal Estuarine Wetlands. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 1020–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, C.S.; Crump, B.C. Microbial Gene Abundance and Expression Patterns across a River to Ocean Salinity Gradient. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.; Li, W.; Lin, B.; Zhan, M.; Liu, C.; Chen, B.-Y. Deciphering the Effect of Salinity on the Performance of Submerged Membrane Bioreactor for Aquaculture of Bacterial Community. Desalination 2013, 316, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remonsellez, F.; Castro-Severyn, J.; Pardo-Esté, C.; Aguilar, P.; Fortt, J.; Salinas, C.; Barahona, S.; León, J.; Fuentes, B.; Areche, C.; et al. Characterization and Salt Response in Recurrent Halotolerant Exiguobacterium sp. SH31 Isolated from Sediments of Salar de Huasco, Chilean Altiplano. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chen, J.; Su, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhang, A. Utilization of Indole-3-Acetic Acid–Secreting Bacteria in Algal Environment to Increase Biomass Accumulation of Ochromonas and Chlorella. Bioenerg. Res. 2022, 15, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Environmental Protection by Aerobic Granular Sludge Process; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-3-7258-0302-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Bo, G.; Shen, M.; Shen, G.; Yang, J.; Dong, S.; Shu, Z.; Wang, Z. Differences in Microbial Diversity and Environmental Factors in Ploughing-Treated Tobacco Soil. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 924137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Xu, Y.-M.; Liang, J.-H.; Huang, W.; Chen, J.-D.; Wu, S.-T.; Huang, X.-H.; Huang, Y.-H.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Sun, H.-Y.; et al. Relationship of Environmental Factors in Pond Water and Dynamic Changes of Gut Microbes of Sea Bass Lateolabrax japonicus. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1086471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, T.; Cai, X.; Li, J.; Zeng, F.; Chen, W.; Wu, Y.; Putri, S.C.D.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Salinity on the Growth, Biochemical Components, and Epiphytic Bacterial Community of Desmodesmus intermedius. Diversity 2025, 17, 751. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110751

Li T, Cai X, Li J, Zeng F, Chen W, Wu Y, Putri SCD, Zhang N, Zhang Y. Effects of Salinity on the Growth, Biochemical Components, and Epiphytic Bacterial Community of Desmodesmus intermedius. Diversity. 2025; 17(11):751. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110751

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Tong, Xiaoyan Cai, Junting Li, Fuyuan Zeng, Wentao Chen, Yangxuan Wu, Shafira Citra Desrika Putri, Ning Zhang, and Yulei Zhang. 2025. "Effects of Salinity on the Growth, Biochemical Components, and Epiphytic Bacterial Community of Desmodesmus intermedius" Diversity 17, no. 11: 751. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110751

APA StyleLi, T., Cai, X., Li, J., Zeng, F., Chen, W., Wu, Y., Putri, S. C. D., Zhang, N., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Effects of Salinity on the Growth, Biochemical Components, and Epiphytic Bacterial Community of Desmodesmus intermedius. Diversity, 17(11), 751. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17110751