Abstract

In areas of high human-elephant conflict, cultivating crops that are less attractive to elephants can be a viable strategy for coexistence. Farmers in these regions often grow crops like pineapple, which are palatable to elephants and attract them into human-dominated landscapes. This study, conducted in Ruam Thai Village, adjacent to Kuiburi National Park in Thailand, evaluated the socio-economic factors affecting farmers’ interest in alternative crop cultivation and assessed the impact of elephants and environmental threats on plots containing pineapple and alternative crops. Our findings revealed that 70% of households (N = 239) rely on pineapple cultivation as their primary source of income. However, 49% of interviewed pineapple farmers reported that their cultivation was not profitable, largely owing to the high costs of agro-chemical inputs. The majority (91%) of farmers experienced negative consequences from living near wild elephants, and 50% expressed interest in cultivating alternative crops. Farmers who frequently experienced elephant visits, felt they could coexist with elephants, and perceived both positive and negative consequences from them were more likely to be interested in alternative crop cultivation. Elephants eliminated over 80% of the pineapple but less than 6% of any alternative crop species across all test plots. Using a crop scoring system based on ecological, economic, and social factors, we identified lemongrass and citronella as the most suitable alternative crop species for the study site. This multidisciplinary study highlights interventions needed to reduce barriers and increase motivators for local farmers to adopt elephant-friendly agriculture as a sustainable human–elephant coexistence strategy.

1. Introduction

Asian elephants (Elephas maximus) are threatened by a multitude of anthropogenic factors [1]. Suitable habitat is increasingly fragmented as conversion to agriculture occurs around protected areas [2,3]. Elephants venture into agricultural plantations as they adapt to fragmented ecosystems, resulting in increasing human-elephant conflict (HEC). The impacts of HEC include damage to crops and property and lethal interactions between humans and elephants [4,5,6]. HEC threatens local livelihoods and the future survival of the endangered Asian elephant [7]. With fewer than 52,000 individuals remaining in the wild [1,8], sustainable solutions that achieve human–elephant coexistence are urgently needed.

In Asia, various local and regional HEC-mitigation strategies have been implemented; however, no single deterrent presents an effective long-term solution [9,10]. Human-made barriers are costly to build and maintain, contributing to a top-down system that lacks community involvement and ownership, ultimately leading to failure or abandonment [11]. These artificial barriers fragment habitat and restrict gene flow between populations [12,13]. Affordable and accessible deterrents are perceived as only somewhat effective, so farmers engage in crop guarding to protect their yield from elephant damage [14,15]. Because most HEC incidents occur at night, farmers responsible for crop guarding often lose sleep, increasing susceptibility to illness and other psycho-social problems [16]. Several studies evaluating the impacts of HEC conclude that adopting land use practices that reduce elephant visitation, such as conversion to less attractive or unpalatable crops, can be a key component in reducing elephant-caused crop damage [11,14,17,18].

In Thailand, suitable habitat has decreased by over half since 1700, with much of that loss recorded between 1950 and 1990 [3]. The country’s remaining elephant population, approximately 4013–4422 individuals, is confined to forest patches surrounded by highly attractive crops and agricultural water supply [19]. When elephants venture into human-dominated landscapes, they encounter active deterrents, such as firecrackers and gunshots, and passive deterrents, such as electric fences and spotlights [20]. However, they are willing to engage in this high-risk behavior to access the calorie-dense, high-quality nutrition that cultivated crops provide [21,22]. The use of pesticides, herbicides and other chemical treatments is pervasive in Thailand’s industrial agricultural production [23]. The negative impacts of chemical-intensive agriculture on farmers’ health and the quality of their local soil, air and water are well-documented [24,25]. Direct and indirect exposure to these chemicals affects invertebrates and thereby threatens birds, amphibians and mammals higher on the trophic chain [26], but little is known about how elephants are impacted by continuous consumption of chemically treated crops. Crop species defended by antifeedants, naturally-occurring chemical compounds that inhibit predation, are less attractive to elephants and other large herbivorous mammals [27,28]. The cultivation of crop species less attractive to elephants could disincentivize visitation and thereby decrease elephant-caused crop damage. Elephants’ crop preferences have been surveyed in both Africa [22,27,29,30] and Asia [28,31,32], but this study represents the first systematic experiment to determine crop palatability to wild elephants in Thailand. The cultivation of less palatable species (hereafter called “alternative crops”) in previous experiments not only disincentivized crop consumption but also presented an economically viable alternative to commonly planted monocrop species [27,28,30].

The adoption of agricultural interventions and HEC mitigation strategies is motivated not only by economics but also by social, psychological and ecological factors [33,34,35]. While previous studies have identified species that are less attractive to elephants, little is known about the barriers that preclude widespread conversion to elephant-friendly agriculture. This dissonance between conservation science and practical implementation may stem from ineffective information transfer and insufficient demonstration of an intervention’s efficacy [36]. When developing and implementing a novel technique, failure to engage end users, in this case, farmers experiencing elephant-caused crop damage, negatively influences adaptive management and adoption [36,37]. Further, farmers are more likely to adopt novel interventions when they are presented by fellow agriculturalists and when several members in their social network adopt first [38]. Understanding the factors that shape the profile of “early adopters” is key to successful diffusion of a novel intervention [39]. Through an intimate understanding of the target demographic, behavior change strategies can be tailored to that group’s experiences and thereby increase the likelihood of project success [40]. Identifying economically viable, ecologically appropriate alternative crop species is important, but elephant-friendly agriculture will only be implemented when the intervention addresses farmers’ perceived motivators, barriers and constraints [35].

We present the first multidisciplinary investigation into the potential for alternative crop cultivation to increase social, ecological and economic resilience in communities coexisting with elephants. We outline a replicable set of steps that can be conducted in other regions experiencing HEC to determine the demographic of farmers who are most interested in adopting this method, the most ecologically appropriate alternative crop species and the agro-economic viability of these species as replacements for those preferred by elephants. Specifically, this study evaluates: (1) which factors shape the profile of farmers who are interested in transitioning to alternative crops, (2) which crop species are least susceptible to elephant-caused elimination, and (3) whether the cultivation of alternative crops is an economically viable alternative to conventional crops.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Site

Ruam Thai Village, located in Kui Buri District, Prachuap Khiri Khan Province, has a population of 2061 individuals and 738 households [41]. The village shares a long, unfenced border with Kuiburi National Park (969 sq km) and is the region’s epicenter of HEC [42]. Local farmers in this region have a complex history with elephants. Before Kuiburi National Park was gazetted in 1999, elephants in this region experienced capture for captivity, poaching and retaliatory killings [42]. In 2003, CITES declared it a Monitoring the Illegal Killing of Elephants (MIKE) target site [20]. Most people cultivate pineapple (Ananas comosus) for their main source of income, and other commonly-grown crops include Pará rubber (Hevea brasiliensis), mango (Mangifera indica), jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) and oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) [14]. Elephant-caused crop damage occurs throughout the year, at all stages of crop maturity, in plots protected by various mitigation methods [14]. The majority of this region’s agricultural zone exists within two kilometers from the forest edge, and the year-round presence of palatable crops means that there is no “safe zone” that is unaffected by elephants [14].

Thailand is the world’s largest producer of pineapple products, exporting over two million tons in 2020 and accounting for almost a third (USD 345 million) of the global canned pineapple market [43]. Most canning factories are in Prachuap Khiri Khan province, providing a guaranteed local market for Ruam Thai farmers’ pineapple yield [42]. However, oversaturation spurs volatility in the crop’s market value, making pineapple farming a precarious and financially unstable livelihood [44]. Further, the village is situated in the rain shadow of the Tenasserim Mountain Range and therefore experiences low rainfall. Water scarcity restricts farmers’ crop species selection, so they choose drought-resistant pineapple despite its palatability to elephants [20]. The economics of pineapple farming is central to elephant conservation and land use planning in this region. Historically, retaliatory killings increased when the pineapple price was high; conversely, farmers abandoned their plots and elephants had unmitigated access to these fallow zones when the pineapple price was low [42]. In this region, human–elephant interactions are a product of socio-economic stability in agriculture-based livelihoods.

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Household Survey and Early Adopter Profile

A 25-question randomly distributed survey (N = 239) was conducted in Ruam Thai Village between 11 October 2021 and 12 December 2021 (Protocol ID: 03868e) (Section S1: household survey template). The survey assessed participants’ demographic information and experiences with elephants and alternative crops. First, participants were asked general information about their current farming practices, including number of plots, land size, ownership, and crop species (Q.3–6). Then, their experiences with elephants were assessed, including their perceived ability to coexist with elephants (Q.7), the frequency that they see elephants (Q.8), the benefits and negative consequences experienced from living nearby elephants (Q.9–14) and the crops cultivated, deterrents deployed and elephant-caused crop damage incurred on their farm (Q.15). Participants’ interest in planting alternative crops as a means of reducing crop damage or elephant visits (Q.16–17), experience with trying this intervention (Q.18–19) and satisfaction with their results (Q.20) were assessed to understand local experiences with alternative crop cultivation. Finally, participants were asked why they had or had not tried alternative crop planting (Q.21–24) to determine the barriers and motivators perceived by farmers.

Questions and response variables were formed in Thai language by co-authors and participants of a Participatory Action Research (PAR) workshop [45] conducted by Bring The Elephant Home and Ruam Thai Village community members before the study began. This participatory approach produced an instrument containing context-appropriate terminology and variables from inception, eliminating the need for translation and back translation.

One representative of each randomly selected household was asked to complete the survey, which took approximately 30 min. Participants had to be above the age of 18 and farm on owned or rented land situated less than two kilometers from the forest edge. Participants completed surveys independently, but a trained enumerator was present to provide instruction if requested.

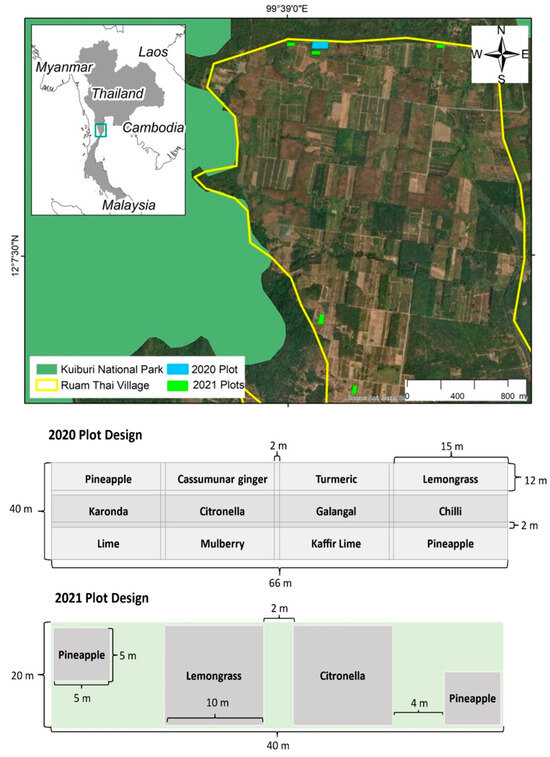

2.2.2. Experiments to Assess Crop Elimination and Elephant Activity

Experimental crop species, planting and cultivation methods and number of crops per rai (1600 sq m) were determined by 19 local farmers during the PAR workshop. A 1.7 rai (2640 sq m) experimental plot (hereafter called the “2020 test plot”) was divided into 12 equally sized sub-plots, each separated by a 2 m-wide walkway (Figure 1). The 2020 test plot was situated less than 20 m from the forest edge, and had pineapple, Pará rubber, and oil palm plantations within 200 m of its east, south and west borders. In this plot, we surveyed elimination of pineapple and 10 experimental crop species: chili (Capsicum frutescens), lemongrass (Cymbopogon flexuosus), kaffir lime (Citrus hystrix), karonda (Carissa carandas), lime (Citrus aurantifolia), mulberry (Morus alba L.), citronella (Cymbopogon nardus), Cassumunar ginger (Zingiber cassumunar), galangal (Alpinia galanga), and turmeric (Curcuma longa). Pineapple was planted in both the closest and farthest sub-plot from the forest edge. Although participating farmers included galangal, Cassumunar ginger and turmeric in the experiment, these species were excluded from data collection and analysis owing to the challenge of assessing the health and condition of these below-ground crops throughout the study period.

Figure 1.

Study site. Top: Kuiburi National Park in southwestern Thailand borders the study site, Ruam Thai Village, where elephant activity was monitored in six test plots located within 125 m from the forest edge. Bottom: The 2020 test plot (1.7 rai/2640 sq m) contained 10 experimental crop species planted in equally sized sub-plots. The five 2021 test plots (0.5 rai/800 sq m) contained lemongrass and citronella. Pineapple was planted in all test plots for comparative analysis. The 2020 test plot and five 2021 test plots were monitored for 22 months and 12 months, respectively.

In 2021, we replicated the experiment focusing on citronella and lemongrass, as preliminary data from the 2020 test plot indicated that these crop species had a shorter crop cycle and were more resistant to elimination by elephants and environmental threats. An equal number (n = 200) of lemongrass, citronella and pineapple crops was planted in five plots (hereafter called the “2021 test plots”). Lemongrass and citronella were planted at a density of one meter by one meter [46,47] and pineapple was planted at the standard density of a commercial farm (3.6 plants per sq m). A 4 m gap was left between the pineapple and experimental crop sub-plots to minimize the risk of incidental damage from elephants. Local farmers and the field staff from Bring The Elephant Home maintained all plots, including monthly weed removal. The 2020 test plot was irrigated weekly in the dry season (November–June) and not irrigated in the wet season (July–October). The 2021 test plots were not irrigated. Agro-chemical inputs were not used in any of the plots.

Upon planting, we randomly selected and marked a subset of individual crops, representing 10% of each species’ sub-plot, for monitoring purposes. Each month, we recorded the height (cm), condition (type and/or cause of damage/elimination), and health (1–5) of each of the pre-selected crops as well as the yield (kg), number of maintenance hours (weeding, irrigation, applying fertilizer), and number of individual crops remaining in each sub-plot (Appendix A).

Further, elephant activity was recorded throughout 428 nights in the 2020 test plot and 365 nights in the 2021 test plots to assess how frequently elephants approached (within 50 m), entered (crossed the plot’s perimeter), and damaged (any interference, including breaking, trampling, uprooting, consuming) the plots. Between 6 September 2020 and 19 June 2022, the 2020 test plot was assessed through direct observations and post-event signs such as dung or footprints. Between 19 June 2021 and 19 June 2022, we recorded the frequency that elephants approached and entered the 2021 test plots through weekly meetings with neighboring guards. As pineapple was fully eliminated in the 2020 test plot after 11 months, we examined whether the frequency that elephants approached, entered or damaged the plot differed when pineapple was present and absent.

In collaboration with PAR workshop attendees, we identified seven criteria to determine the suitability of alternative crop species for the ecological, economic and social contexts in Ruam Thai Village (Appendix B). Ecological criteria included resilience to elephants, resilience to environmental threats and crop health. Scores were determined from total crop elimination by elephants and environmental threats and mean health recorded in the 2020 test plot. Economic criteria included input requirements and profit potential, and scores were determined based on the treatments that each species required and the yield/profit that was produced in the 2020 test plot. Social criteria included labor investment and local familiarity. The labor investment score was determined by the maintenance hours recorded in the 2020 test plot and substantiated by personal communication with farmers managing the plots. Local familiarity was determined by household survey responses for crop species currently grown in plantations (Q.6) and alternative crops that had been planted in plantations (Q.19) and substantiated by personal communication. We scored each species from 1–3 on each criterion, with a score of 1 indicating low suitability, 2 indicating moderate suitability and 3 indicating high suitability. The mean scores from the ecological, economic and social categories were summed for each crop, allowing a maximum possible score of 9.

2.2.3. Farmer Interview and Agro-Economic Viability

To determine the profitability of pineapple cultivation, we conducted structured interviews (N = 71) with randomly selected pineapple farmers with farms located within two kilometers of the forest edge (Section S2: pineapple farmer interview template). While household survey participants included people who farmed any crop species, this interview only included pineapple farmers. Interviews were conducted between 19 July 2022 and 14 October 2022. Participants had to be above the age of 18 and were not asked to give their name or other identifying information. Only one participant per household was asked to respond to interview questions, and no financial compensation was offered.

The interview consisted of two sections. First, demographic data about farmers and their plots were gathered through multiple-choice and open-ended questions. Second, data on financial investment into planting, maintenance, elephant deterrents and harvesting were collected using a comprehensive list of expense items, including pineapple cultivars, equipment (irrigation systems, electric fencing), agricultural supplies (fertilizer, herbicide, induction hormone), labor (hired day laborers to plant, water, weed and/or harvest), transportation (cultivar delivery or yield transport to sales point) and other expenses incurred by the participant. Participants were asked to distinguish between “hired labor” and “farm owner labor” when describing their investment costs. Then, participants estimated economic loss from elephant-caused damage. Revenue was assessed by multiplying farmers’ combined yield by the market value at the time of sale. To reduce recall bias, farmers were asked to provide investment, elephant-caused damage and revenue data from their most recent planting period [48], which can contain up to three pineapple harvests.

We assessed the profitability of lemongrass and citronella using data from this study’s 2021 test plots. Since each of the five 2021 test plots contained 200 sq m sub-plots of both lemongrass and citronella, we multiplied the mean results by eight to compare the economics of cultivation within 1 rai (1600 sq m) plots.

Both lemongrass and citronella produce stalk and leaf yield. Lemongrass stalk is commercially processed into culinary, aromatherapy, cosmetic and pharmaceutical products [49,50]. Citronella is predominantly grown for its leaf yield, but the stalks are sold for propagation. Lemongrass and citronella leaf yield is used to produce essential oils. To monitor market fluctuation and determine the mean market value, we recorded the minimum and maximum market value for pineapple, lemongrass and citronella on a weekly basis throughout the 2021 planting season (19 June 2021–19 June 2022). Market values were collected by contacting local purchasing centers and factories and referencing national agricultural pricing websites (https://talaadthai.com; https://www.kasetprice.com/; https://www.simummuangmarket.com/en/ (accessed on 19 June 2021)).

We used a 25 L pressurized distiller at Kasetsart University’s Faculty of Agriculture to extract essential oils from 6.5 kg samples of our lemongrass and citronella leaf yield (Figure 2). We calculated potential essential oil revenue based on published economic data for lemongrass oil (USD 6.2/kg) and citronella oil (USD 8.6/kg) extracted from yield cultivated in conditions similar to our experimental plots [49].

Figure 2.

Harvesting and processing stages. (a) Mature citronella leaf yield is harvested from the 2020 test plot using a sickle. (b) Stalk yield is then unearthed, cleaned, and tied in bundles containing equal stalks in preparation for sale or replanting. (c) An industrial hydrodistillation machine is used to extract essential oil from leaf yield. (d) The essential oil, valuable, concentrated oil extracted from plant matter is separated from hydrosol, a diluted byproduct from the distillation process that can be used in cosmetic and aromatherapy products.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.3.1. Household Survey and Early Adopter Profile

To evaluate which factors influence farmers’ interest in alternative crop planting, we conducted a binomial logistic regression analysis. Five variables were assessed from the household survey data (N = 239): frequency of elephant visits to the farm (never, less than once per month, once per month, once per week, several times per week, every night), perceived benefits from elephants (no, yes), total land size (rai) (1–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16+), age (18–35, 36–45, 46–55, 56–65, 66+) and gender (male, female). We used the best subset selection method to determine variables that shape the profile of farmers who are interested in alternative crop planting. We fit separate models for each possible combination of predictors. We used Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) to choose the best overall model and selected the model with the lowest BIC (Appendix C).

Initially, we included perceived ability to coexist with elephants (no, yes) and perceived negative consequences from elephants (no, yes). However, we excluded these parameters from the logistic regression analysis because a Cramer’s V test revealed that benefits from elephants had a strong association with perceived ability to coexist (Χ2 = 38.9, p < 0.0001; Cramer’s V = 0.4137) and frequency of elephant visits had a strong association with negative consequences (Χ2 = 49.0, p < 0.0001; Cramer’s V = 0.4527). Though we removed them from the logistic regression analysis, we used a chi-square test to assess the relationship between each of them and participants’ interest in alternative crop planting. Tests were performed using R version 4.2.0 [51].

2.3.2. Crop Elimination and Elephant Activity

To determine the overall influence of pineapple presence on elephant activity in and around the plots, we used a chi-square goodness of fit test to assess differences in the frequency that elephants approached, entered and caused damage in the 2020 test plot before and after pineapple was eliminated from the plot. Tests were performed using R version 4.2.0 [51].

2.3.3. Farmer Interview and Agro-Economic Viability

We determined each species’ profitability by subtracting all investment costs (planting, maintenance, elephant deterrents and harvest) and elephant-caused crop damage from revenue. We divided all investments and revenue by the number of rai cultivated to standardize comparisons between participants with varying plot sizes. Since each species varies in duration from planting to harvest, we divided the profit per rai by the species’ crop cycle length (months). We excluded farm owner labor from the analysis, as is standard practice in agro-economic analyses [38]. We divided elephant deterrents into recurring costs, such as firecrackers, and non-recurring costs, such as electric fencing and spotlights. We only included non-recurring costs in profitability analyses for farmers who reported economic data from their plot’s first crop cycle, so as to represent investments consistent with those incurred during the establishment of their plot. Recurring costs were factored into each participants’ analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Household Survey and Early Adopter Profile

The majority of farmers plant pineapple as their main source of income (69.9%), with Pará rubber (29.7%), mango (23.4%), jackfruit (16.3%) and 12 other species cultivated in the region. While monocrop farming is standard (47.3%), some farmers cultivate two species (37.2%), three species (10.5%), or more than three species (5.0%). Farmers reported seeing elephants in and around their farms to varying degrees of frequency, ranging from at least once per week (37.2%), less than once per month (27.2%), and once per month (18.8%), and an equal number of participants reported never being visited as those who are visited every night (8.4%).

The majority (90.8%) of participants reported negative consequences from living near wild elephants. These consequences include worry that elephants might damage crops or property (77.4%); economic losses from crop damage (77.0%); risk, fear, worry or stress while traveling to/from night guarding (70.0%); injury or loss of life to themself or someone in their community (62.7%); loss of sleep (59.0%); sadness, embarrassment, disappointment, or hopelessness when discovering crop damage (45.2%); property damage (36.9%); and isolation or loss of social time with family/friends (31.8%). Economic losses from crop damage were perceived to have the greatest impact on quality of life (35.9%), followed by injury or loss of life to themself or someone in their community (21.2%) and risk, fear, worry and/or stress while traveling to/from night guarding (17.1%).

Only one-third of participants (35.6%) reported experiencing benefits from living nearby elephants. These benefits included financial benefits from elephant-related tourism, employment, events, or other activities associated with wild elephants (71.8% of those reporting benefits), pride, joy, excitement, and/or interest when seeing wild elephants (30.6%), social cohesion, teamwork, and/or community spirit in working with neighbors on elephant-related events or initiatives (27.1%), participating in or hosting trips, meetings, and/or skill development workshops relating to elephant conservation or HEC mitigation (20.0%), and cultural, religious and/or spiritual benefits from being around wild elephants (16.5%). The majority of participants who reported experiencing benefits of living near elephants indicated that financial benefits were the most important to them (67.1%).

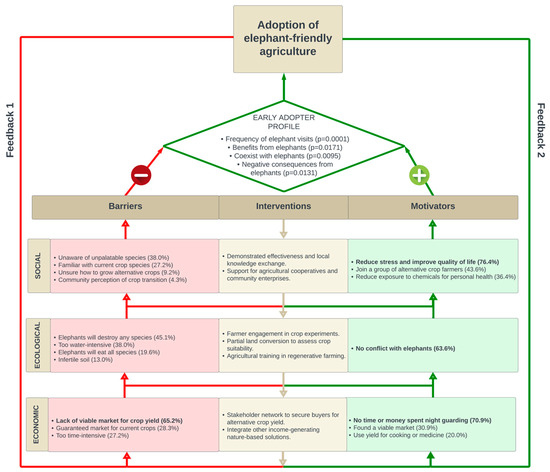

Half of the household survey participants (50.2%) were interested in alternative crop planting as a means of reducing crop damage and elephant presence on their farms. The absence of a viable economic market is a clear barrier to adopting alternative crops, as 65.2% of farmers cite this as a reason for not trying alternative crop planting, while almost every farmer (98.3%) interested in alternative crop planting indicated that a guaranteed market is vital to adoption. Further, 51.7% require more training, resources and information about farming techniques and viability of their soil/land before planting, 24.2% are willing to plant crops that have a lower economic value if they decrease elephant presence and damage, and 23.3% want others to adopt the method before implementing it themselves. Some farmers (23.0%) had tried alternative crop planting, and 47.3% of that group were satisfied with their results. The main reasons for planting alternative crops were reducing stress and worry and improving quality of life (76.4%), no longer wanting to spend time or money guarding crops at night (70.9%), and no longer wanting to be in conflict with elephants (63.6%). Those who were not interested in alternative crop planting (49.8%) reported that the main barriers to planting alternative crops were a lack of viable market for crop yield (65.2%), their belief that even if elephants do not eat the crops, they will still trample and uproot them (45.1%), that crop species that elephants do not eat require too much water (38.0%) or that they were not aware of any crop species that elephants do not eat (38.0%).

Farmers were more likely to be interested in alternative crop planting when their farms were visited more frequently by elephants (Table 1). Though all frequency categories were significantly associated, the likelihood was higher for farmers who were visited by elephants at least once per week. Farmers who experienced benefits from living near elephants were more likely to be interested in alternative crop planting than those who did not perceive benefits (1.92 [95% CI: 1.05, 3.57]). Though excluded from logistic regression analysis, chi-square tests determined significant associations between interest in planting alternative crops and perceived ability to coexist with elephants (p = 0.0095) and perceived negative consequences from living nearby elephants (p = 0.0131).

Table 1.

Logistic regression results with a 95% confidence interval (CI) on odds ratio. “*” indicates outcomes that were significantly (p < 0.05) associated with interest in planting alternative crops as a means of reducing crop damage and elephant presence in farms (household survey, Q.16).

3.2. Crop Elimination and Elephant Activity

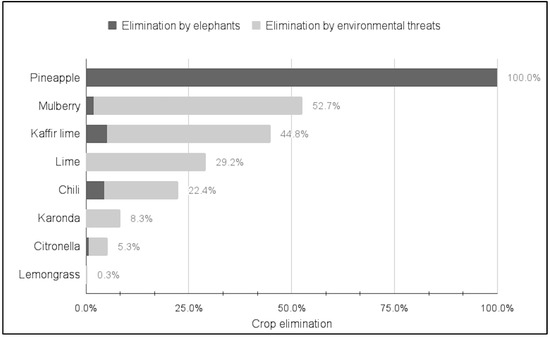

In the 2020 test plot, elephants eliminated 96.5% of the pineapple within two months and completely eliminated the pineapple within 11 months (Figure 3). All pineapple crops were eliminated through full or partial consumption. Elephants did not consume or uproot any of the experimental species, but kaffir lime (5.2%), chili (4.4%) and mulberry (1.8%) experienced some elimination by trampling. Environmental threats such as drought, invertebrate depredation, and insect-transmitted diseases caused some elimination in all experimental species (Appendix D). Farmers attributed elimination from environmental threats in kaffir lime (39.7%), lime (29.2%) and chili (18.0%) to the chemical-free cultivation practices, reporting that applying insecticides to immature crops would be standard practice to reduce invertebrate depredation in these species. Mulberry elimination (50.9%) was predominantly due to unsuccessful germination, likely resulting from poor-quality cultivars.

Figure 3.

Crop elimination. In the 2020 test plot, pineapple elimination was primarily due to elephants, while alternative crop loss was mainly due to environmental threats such as drought, invertebrate depredation, and insect-transmitted diseases, though to a lesser extent. Elephants entered the plot on 64 nights and did not consume or uproot any experimental species, although some were eliminated by trampling. Pineapple was fully eliminated by elephants and lime, karonda and lemongrass did not experience elephant-caused elimination.

Throughout 428 observation nights in the 2020 test plot, elephants approached the plot on 157 nights (36.7%), entered on 64 nights (15.0%) and caused damage on 25 nights (5.8%) (Appendix E). Most damage events (88.0%) occurred while pineapple was still present. Once all pineapple crops had been eliminated, the frequency that elephants approached (χ2(1) = 22.17, df = 1, p =< 0.001), entered (χ2(1) = 22.56, df = 1, p =< 0.001) and damaged (χ2(1) = 14.44, df = 1, p =< 0.001) the plot significantly decreased. Elephant-caused crop damage only occurred on three occasions following the elimination of pineapple. Elephant dung and footprints were often found beside alternative crops in the pathways between species or space between crop rows (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Elephant activity. Elephant dung and footprints in the 2020 test plot revealed that elephants navigated the plot using pathways and crop rows, infrequently trampling experimental crops despite the recurring presence of elephants in the plot. These observations differ from hypotheses set by farmers during the pre-planting Participatory Action Research (PAR) workshop, which reflected a widely held notion that elephants would eliminate just as much alternative crop yield by trampling and uprooting as they eliminate in pineapple plots by consumption.

Across all five 2021 test plots, elephants eliminated 80.8% of the pineapple but only 1.8% and 1.7% of the lemongrass and citronella, respectively. All pineapple elimination was caused by partial or full consumption, and all lemongrass and citronella loss was caused by trampling. Elephants eliminated all pineapple crops in two of the five test plots. Environmental threats (drought) eliminated 2.4% and 3.9% of the lemongrass and citronella, respectively. Throughout 365 observation nights, elephants approached on 131.4 nights (36.0%) and entered on 46.6 nights (12.8%).

The crop scoring system determined that lemongrass is the most suitable alternative crop in the local context of Ruam Thai Village, closely followed by citronella (Table 2). Their resilience to both elephants and environmental threats, short crop cycle with a competitive market value, and minimal startup investment and maintenance time all contribute to these species’ ecological, economic and social suitability as a viable alternative to pineapple in Ruam Thai Village. Lime and kaffir lime scored the lowest owing to the long period before financial return (approximately three years until first yield), intensive investment needed to irrigate and prevent invertebrate depredation, and lack of local familiarity with large-scale cultivation practices for these species.

Table 2.

Alternative crop scoring. Each crop species was scored on seven criteria to assess their suitability for the ecological, economic and social contexts in Ruam Thai Village, Thailand. Scores were assigned based on data collected in the 2020 test plot throughout the 22-month study period, household survey responses and personal communication with farmers involved in plot maintenance. A score of 1 indicates low suitability, 2 indicates moderate suitability and 3 indicates high suitability. The maximum possible score for each species is 9.

3.3. Farmer Interview and Agro-Economic Viability

The comparative economic analysis revealed that both lemongrass and citronella are more profitable than pineapple (Table 3). Investment and revenue data were reported from 104 harvest cycles of 71 farmers. Investments exceeded revenue in 41.3% of harvest cycles, and nearly half (49.2%) of the interviewed farmers’ cultivation was not profitable in their most recent planting period. Pineapple farmers cultivated a mean land size of 7.7 rai (SD = 7.6) located 966.3 m (SD = 665.2) from the forest edge. The mean crop cycle was 13.3 months (SD = 2.2), during which farmers planted 5762 pineapple trees (SD = 1106.1) and yielded 2366.7 kg/rai of fruit (SD = 1758.7). The mean market value at sale time was USD 0.17/kg (SD = 0.05), providing a mean total revenue of USD 416.6 (SD = 334.6). Per rai, farmers spent USD 161.7 on maintenance, USD 100.9 on planting, USD 49.3 on harvesting and USD 38.3 on elephant deterrents. Elephant-caused crop damage accounted for further economic loss of USD 38.5/rai. The mean profitability of pineapple cultivation was USD 27.8/rai or USD 2.1/rai per month throughout the crop cycle.

Table 3.

Agro-economic analysis. Our analysis compared the profitability of lemongrass and citronella, the two most suitable alternative crops, to that of pineapple, the most commonly grown commercial crop in Ruam Thai Village, Thailand. Economic data for pineapple were collected in farmer interviews (N = 71), and lemongrass and citronella data were based on investment/loss and yield from this study’s 2021 test plots. These data represent the mean investments, loss, revenue and profit per rai (1600 sq m) and were collected in Thai Baht (THB) and converted to US dollars (USD) (USD 1 = THB 36.63).

Maintenance was the highest investment category for most pineapple farmers owing to the cost of chemical fertilizer and herbicide. In response to the question “what are the main challenges of your job as a pineapple farmer?” 24.0% reported high fertilizer prices and investment costs, which was the second most frequent theme mentioned following elephant-related challenges (29.0%). Farmers lost a mean of 9.2% of their yield to elephant-caused crop damage, and it accounted for over 30% yield loss for 10 farmers and over 90% yield loss for two farmers. Farmers spent a mean of 31.7% of their nights guarding their farms. Even though immature pineapple is susceptible to elephant-caused crop damage, some farmers only guard when mature pineapple is nearing harvest. Over two thirds (69.0%) of farmers guarded their pineapple at some point during the crop cycle and 26.8% of farmers guarded their crops every night. All interview data were included in our analysis.

We planted 200 lemongrass and citronella plants in 200 sq m sub-plots in each of the five 2021 test plots, totaling 1000 plants of each species. After 12 months of observation, 95.8% of the lemongrass and 94.4% of the citronella had survived and was harvested. Lemongrass plots generated 1938.5 kg of stalk yield and 829.5 kg of leaf yield. Citronella plots generated 1888.0 kg of stalk yield and 868.5 kg of leaf yield. Throughout this 12-month period, the mean market value of lemongrass and citronella stalk yield was USD 0.48/kg and USD 0.33/kg, respectively. The yield from these test plots was not sold commercially but was used for propagation in Ruam Thai Village; however, our results suggest the potential revenue from lemongrass and citronella stalk yield to be USD 1490.3/rai and USD 989.6/rai, respectively. In addition to commercial sales, these results highlight the long-term self-sufficiency accessible to farmers through lemongrass and citronella cultivation. Based on our study’s yield, harvesting 1 rai of lemongrass and citronella can generate enough cultivars to propagate 22.9 rai and 20.1 rai of these species, respectively. Given that pineapple farmers currently cultivate a mean 7.7 rai, the need to purchase and transport cultivars could be eliminated within one crop cycle should farmers decide to transition. Our hydrodistillation trial yielded 2.9 mL/kg of lemongrass oil and 7.5 mL/kg of citronella oil. While this was just a sample of our yield, applying this output ratio to the total leaf yield from our plots suggests an extraction potential of 3.8 L/rai (USD 23.8/rai) and 10.4 L/rai (USD 89.4/rai) of lemongrass and citronella oil, respectively. Including the sale of stalks and essential oil, the projected revenue from lemongrass and citronella cultivation was USD 1514.0/rai and USD 1079.0/rai, respectively.

Investments totaled USD 421.6/rai and USD 363.9/rai to cultivate lemongrass and citronella, respectively. Though elephants only eliminated minimal amounts of lemongrass (1.8%) and citronella (1.7%), the value of each individual crop is higher for these species, which cause elephant-caused damage to appear comparable to pineapple in our analysis. The profit potential of lemongrass is USD 1092.5/rai, and based on the seven-month crop cycle [47], this equates to a monthly profit of USD 156.1/rai. Citronella’s four-month crop cycle [46,52] gives this species the highest profit potential, generating USD 715.1/rai and a monthly profit of USD 178.8/rai.

We evaluated the economic equivalent of farm owners’ personal time invested into cultivation as well as the cost of hiring additional laborers. We calculated farm owners’ labor costs by multiplying 8 h of labor by the region’s standard daily wage for agricultural labor (USD 8.2) and nightly wage for crop guarding (USD 5.5). Farm owners’ mean time spent cultivating (planting, maintaining and harvesting) their pineapple equated to USD 78.8/rai, and time spent night guarding equated to USD 158.6/rai. However, farm owners’ labor was excluded from the profitability analysis. Notably, this study’s lemongrass and citronella plots were managed by hired laborers, which increased the investment reported in the analysis. If farm owners adopt elephant-friendly agriculture and manage their own plantations, they would experience lower investment, and therefore higher profit, than reported in this study.

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that intangible costs from living nearby elephants motivate interest in adopting elephant-friendly agriculture. The desire to reduce stress and improve quality of life and reduce time and money spent night guarding were the most common motivators for those who had tried alternative crop planting. Given that “worry that elephants might damage crops/property” and “economic losses from crop damage” are experienced almost equally (77.4% and 77.0%, respectively), our results emphasize the need for holistic strategies that go beyond the mitigation of tangible costs (crop damage) and address intangible costs experienced by farmers coexisting with elephants [53,54]. Unsurprisingly, our results indicate a unified need for a reliable buyer before farmers transition their agricultural practices. Though a transition could simultaneously reduce tangible and intangible costs of coexisting with elephants, crop selection in Ruam Thai Village is not determined by profitability but by certainty of sale. Although the economic analysis revealed pineapple farmers’ poor return on investment, their proximity to pineapple processing factories provides much-needed assurance to farmers experiencing diminished socio-economic resilience.

The household survey revealed that over half of the participants (52.7%) are currently farming more than one crop species and that fifteen different crop species are grown at commercial scale in the study site. While monocrop pineapple cultivation is the norm, variation in crop selection and configuration is already practiced in the study site. Therefore, adopting a new crop may not be as difficult as previously anticipated. In fact, our results suggest that low alternative crop adoption rates are attributed to local misconceptions about how elephants will interact with these alternative species and a lack of awareness about which species are unpalatable to elephants. Though it should be noted that demonstration does not necessarily lead to adoption, the lack of visible efficacy of alternative crop planting may be impacting farmers’ uptake [34]. Upon harvesting the test plots, eight farmers who joined the PAR workshop or participated in data collection and plot maintenance requested lemongrass and citronella cultivars from the 2020 test plot landowner. These farmers may have perceived the same barriers as other survey respondents before the crop trials, but their involvement in monitoring crop health, survival and yield removed these barriers and motivated adoption. This highlights the importance of participatory and community-based study designs with local people involved in every step of the scientific process [35].

Our results suggest that the early adopter profile is shaped by experiencing both costs and benefits from elephants. In Ruam Thai Village, interest in alternative crop planting is motivated by the high frequency of elephant visits, perceived negative consequences as well as access to benefits from elephants and perceived ability to coexist with elephants (Figure 5). Nearly half (45.6%) of surveyed farmers see elephants in/around their farms at least weekly, resulting in the majority (90.8%) experiencing negative consequences. Conversely, only a third (35.6%) of farmers experience benefits from elephants, and less than a quarter (22.6%) feel they can coexist with elephants. These findings align with other social studies of communities coexisting with elephants, where costs, such as a high frequency and severity of elephant-caused crop damage, prompted negative attitudes towards elephants [55,56] and access to benefits motivated tolerance and willingness to coexist [5,54]. Our results illustrate that early adopters are farmers who experience sufficient costs from elephants to motivate a transition, while simultaneously experiencing benefits that foster willingness to adopt strategies that enable coexistence. Determining the factors that shape the early adopter profile enables community-based conservation planning among farmers who have similar experiences with elephants. More participants and higher crop yield allow farmers to negotiate more competitive prices from buyers, coordinate shipments to reduce delivery costs and benefit from increased social resilience as a result of a collective approach.

Figure 5.

Early adopter profile. The profile of an early adopter, a farmer most interested in elephant-friendly agriculture, is shaped by four parameters determined from the household survey responses. Farmers experience barriers and motivators in social, ecological and economic domains, and the presence and absence of both barriers and motivators affects interest in elephant-friendly agriculture. The interventions in each domain are key to minimizing the barriers and maximizing the motivators, so more farmers adopt and experience success, which contributes to the positive feedback loop that enables more widespread adoption. Barriers and motivators in bold were reported by the majority of participants.

Following the experimental crop trials, farmers in Ruam Thai Village formed a community enterprise to synchronize the cultivation and sale of alternative crop yield. The group is pursuing both Fair Trade and Good Agricultural Practices certifications and has coordinated training workshops and site visits with industrial buyers, university professors and Department of Agriculture representatives. This collective action may be perceived as onerous, but our observations align with other studies that suggest that community collaboration to mitigate HEC is perceived positively by farmers [57] and that the shared challenges of coexistence can even foster social connections [16,58]. These findings demonstrate that a community-based model is vital to farmer adoption and sustained satisfaction. Further research is needed to identify and align stakeholder objectives in order to remove social, ecological and economic barriers to alternative crop cultivation in communities seeking human-elephant coexistence.

This study represents the first assessment of crop palatability to wild elephants in Thailand, and the results suggest that several alternative crop species are not attractive to elephants. Our results were consistent with studies in other regions; however, elephants entered the six test plots a combined 297 times throughout the study period, which is higher than the 11 visits in Nepal [28], 13 visits in Vietnam [32], 18 visits in Zambia [27], and 43 visits in Botswana [22]. Using camera traps and individual elephant identification to analyze the demographic diversity of elephant visitors would provide more detailed insight into different elephants’ interaction with these species.

Elephants are highly adaptable, generalist foragers [59]. They may begin to consume crops that were previously believed to be unpalatable, as observed in coffee plantations in India [60]. Monitoring elephant interaction with experimental species of varying morphologies throughout their growth cycle is key, since the seasonality and maturity of the crop affects its palatability to elephants [22,31]. Elephants are known to target both native and cultivated fruit-producing trees [14,61]; however, kaffir lime, karonda, and lime, did not reach full maturity or produce fruit during the study period. Similarly, while they were excluded from the crop comparison analysis, galangal, turmeric, and Cassumunar ginger were not consumed by elephants, perhaps owing to the morphological characteristics of these species’ below-ground yield [18,22]. A longer study period and increased plot replication would inform how elephants interact with these species throughout their crop cycle.

Localized crop trials are important before large-scale conversion to ensure selected species are unattractive to elephants and ecologically appropriate in the target landscape [22]. For example, African elephants consume both lemongrass [27,29] and citrus fruits [62], but these were avoided in our experiment and others situated in Asian range countries [28,32,63]. Elimination by environmental threats exceeded elimination by elephants in experimental species, owing to drought, invertebrate depredation and insect-transmitted diseases. Further study is needed to identify locally accessible and ecologically suitable solutions that mitigate these environmental threats. Farmers should be engaged in alternative crop selection, and native species that are resilient to local ecological conditions and require minimal inputs should be prioritized.

Evaluating the relationship between crop species and soil health was beyond the scope of our study, but this is vital to the success of agricultural transitions. Long-term pineapple cultivation and exposure to agricultural chemicals deteriorate soil quality and fertility [24,64]. Some household survey respondents (13%) cited infertile soil as a barrier to alternative crop cultivation. Partnerships between local farmers, agricultural scientists and government entities are needed to incentivize regenerative agricultural practices and support farmers as they transition crop species. Future studies should investigate the influence of alternative crop cultivation on soil health and other biodiversity indicators to determine suitable replacements for elephant-preferred crop species.

Our results suggest that alternative crops are not repellent or deterrent by nature, but that replacing attractive species with alternative crops disincentivizes the presence of elephants and decreases elephant-caused crop damage if and when elephants do enter farms. However, to revitalize the agro-ecological system at a landscape level, shifting from one monocrop to another is not the ultimate solution. Polycropping and agroforestry models can mitigate elephant-caused crop damage while simultaneously increasing a farm’s economic viability [32] and regenerating degraded land [65]. Implementing buffer crops (planting alternative crops around the perimeter of palatable species) has decreased elephant-caused crop damage in other regions [22,58], which may allow farmers to assess the economic and ecological suitability of alternative species before a full transition. However, monitoring elephant activity in the 2020 test plot revealed that elephants approach, enter and cause damage more frequently when palatable crops are present. We anticipate that tangible and intangible costs are inevitable while commercial production of palatable crops continues.

Given that input costs and market value are constantly fluctuating, the results of our economic analysis are not meant to represent a fixed definition of pineapple’s profitability. However, these results underscore perpetual challenges faced by this region’s pineapple farmers, including the high cost of chemical inputs [23,25], financial vulnerability caused by agro-industrial market oversaturation [43] and unpredictable trends in elephant-caused crop damage [14]. Thailand is one of the leading consumers of agro-chemical inputs, and pesticide intoxication and other illnesses stemming from exposure to agro-chemicals have become a public health concern for Thai farmers [23,25]. The household survey revealed that of those that had already tried alternative crop planting, 36.4% selected “I wanted to cultivate crops which do not require chemical fertilizers or sprays out of concern for my health” as a motivator for attempting the transition. Several of the alternative crop species surveyed in this study can be grown without the use of chemical inputs. Agricultural certifications can incentivize farmers to decrease reliance on costly inputs while simultaneously increasing the value and marketability of their yield [66].

The potential for market diversification makes lemongrass and citronella viable economic alternatives to pineapple. Globally, the essential oil market exceeded USD 7.51 billion in 2018 with a projected annual growth of over 9% [67]. Some of the most widely-produced oils, including peppermint, lemon and citronella, are extracted from species that happen to be unpalatable to Asian elephants [28,58]. The revenue described in our analysis for lemongrass and citronella represents only a fraction of these species’ economic potential. Other experiments using similar growing conditions, crop maturity, and extraction methods yielded 5.5 times more citronella oil [52] and 4.4 times more lemongrass oil [50] than yielded in our study. This is likely because our 2021 test plots were unirrigated, which can reduce essential oil yield by up to 50% [49]. Also, our samples were distilled eight hours post-harvest, and increasing time from harvest to distillation decreases essential oil yield [50].

Their short crop cycle further amplifies the economic potential of lemongrass and citronella [28]. Irrigated citronella reaches optimum quality four months after planting [46,52], so citronella can produce three yields within the same timeframe as the average pineapple cycle (13.3 months). The cost of purchasing an industrial hydrodistillation machine was not factored into the economic analysis. Thailand hosts a vast network of community agricultural cooperatives, and these groups of smallholder farmers leverage collectivism to scale their production, negotiate yield price and access education and training opportunities [23]. If cooperatives can share these startup costs to secure processing equipment, it could increase profitability, create job opportunities and foster social cohesion [46,49].

In addition to poor return on investment, our results underscore the hidden costs of cultivating palatable species, namely the sustained need for resource-intensive crop guarding [68]. Nightly guarding leads to opportunity costs for pineapple farmers, impacting their ability to engage in income-generating activities [54,69]. A transition to alternative crops holds the potential to increase the profitability of production, but once farmers are unburdened from night guarding responsibilities, increased capacity to pursue meaningful employment and livelihood diversification opportunities may also contribute to financial wellbeing. Combining elephant-friendly agriculture with other nature-based solutions can deter elephants and generate additional socio-economic benefits. During the study, local farmers who joined the PAR workshop and plot maintenance activities established a social enterprise called the Tom Yum Project, named after a popular Thai soup that contains several of the experimental crop species profiled in this study. The group incentivizes local cultivation of alternative crops by purchasing yields from participating farmers, processing them into “elephant-friendly” products, and selling them locally and internationally. This community-driven initiative has been acknowledged internationally for fostering skill development, capacity building and alternative livelihoods that catalyze human–elephant coexistence [70]. Further, bees inhabiting beehive fences could pollinate alternative crops, simultaneously boosting the farm’s yield and local biodiversity [29] while deterring elephants from entering farmland [10]. The 2020 test plot landowner observed an increase in native bees owing to the presence of flowering crops and chemical-free cultivation practices (Phibunwattanakon, T. 19 June 2022. Personal communication). The presence of native pollinators, such as the Asiatic honeybee (Apis cerana) and stingless bees (Trigona laeviceps) can increase yields of diverse, marketable products such as beehive fence honey and chili [71]. Chili itself is unpalatable to elephants [29,30], and chili-based deterrents such as spicy beehive fences [72] and chili fences and briquettes [73,74] hold the potential to decrease elephant-caused crop damage through locally accessible interventions. Combining these nature-based solutions promotes a holistic approach to coexistence that reconciles the needs of humans, elephants and the ecosystems they share.

5. Conclusions

This study presents novel insight into the potential for alternative crop planting to bring social, ecological and economic benefits to farmers coexisting with elephants by concurrently increasing psycho-social well-being, crop yields’ resilience to elephants, and financial return on investment. It outlines a sustainable, community-based intervention that gives local people the agency to disincentivize the presence of elephants in their own farms and access benefits from elephants through elephant-friendly land-use practices. Our findings suggest that alternative crop adoption hinges on reliable and equitable markets for farmers’ yield and systems that support farmers’ capacity for adaptive management. Therefore, a transition to elephant-friendly agriculture depends on a robust multi-level stakeholder network and government-issued policies that incentivize agricultural practices with positive outcomes for local livelihoods, human health, ecosystem restoration and, in turn, elephant conservation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d16090519/s1: Supplementary materials including the household survey template (Section S1), the pineapple farmer interview template (Section S2) and a Thai-language abstract (Section S3).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.O., A.v.d.W., S.S. and K.M.; methodology, A.O., A.v.d.W., N.S., N.T., S.S., A.R. and K.M.; project administration, A.O., A.v.d.W., N.S., N.T. and S.S.; data curation, A.O., N.S., S.S., A.R. and K.M.; formal analysis, A.O., A.R. and K.M.; visualization, A.O., A.v.d.W. and N.S.; supervision, A.v.d.W., N.T. and K.M.; writing—original draft, A.O.; writing—reviewing and editing A.O., A.v.d.W., N.S., N.T., S.S., A.R. and K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Bring The Elephant Home, Fondation Ensemble (grant number: n° PP/EAD/2021/03), LUSH Charity Pot, Marjo Hoedemaker Elephant Foundation, Nonthaburi Neighborhood Reach and Franci Blanco.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This experiment’s crop damage enumeration methods were approved by Miami University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Project Number: 897_2022_Oct) and Institutional Review Board (Protocol ID: 03558e, 10 June 2020). Data collection involving human subjects was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Miami University’s Institutional Review Board (Protocol ID: 03868e, 11 June 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participating human subjects.

Data Availability Statement

The data reported in this study are available from the corresponding author (AO) upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ruam Thai Village community members who joined participatory activities to design the experimental plots, select crop species, collect data, and maintain and harvest the crop yield, namely Thanasit Phibunwattanakon, who inspired the study and welcomed the 2020 test plot to be planted on his land. We thank Nitiphat Nenkwen, Ruam Thai Village chief, for approving the study methods and offering vital insight on the study’s objectives. Students and faculty members of Miami University’s Project Dragonfly, namely Lily Maynard, Katie Feilen and Karen Plucinski, are due thanks for providing insight and support throughout the study. We also thank Eva Gross for sharing experiences from alternative cropping experiments in other range countries and Khamarat Chorchuvong for sharing product-making expertise with the Tom Yum Project’s members.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The data collection sheet used to conduct monthly surveys to evaluate each experimental species’ susceptibility to elimination by elephants and environmental threats.

Table A1.

The data collection sheet used to conduct monthly surveys to evaluate each experimental species’ susceptibility to elimination by elephants and environmental threats.

| Condition | Code |

| Partly Consumed. Eliminated | PCE |

| Partly Consumed. Intact | PCI |

| Fully Consumed | FC |

| Uprooted. Not consumed | UNC |

| Trampled/Broken. Eliminated | TE |

| Trampled/Broken. Intact | TI |

| Missing | MI |

| Eliminated. Drought | ED |

| Eliminated. Invertebrate depredation | EP |

| Eliminated. Other environmental threats | EE |

| Disease | DI |

| Health | Score |

| Eliminated—completely dead/dried up, missing. | 1 |

| Poor—withered, fallen/drooping, all leaves are dry. | 2 |

| Average—standing, partially dry, no new growth. | 3 |

| Good—green/new growth/shoots, some fruiting or flowering. | 4 |

| Thriving—entire plant green, many shoots, fruiting, flowering. | 5 |

| Maintenance | Hours |

| Weeding, watering, mulching, applying fertilizer | |

| Height | Centimeters |

| From base of the plant to the top of the tallest leaf |

Appendix B

Table A2.

We used data collected from experimental crop trials, the household survey and the pineapple farmer interview to score each species on seven criteria and determine their overall suitability in the local context of Ruam Thai Village, Thailand.

Table A2.

We used data collected from experimental crop trials, the household survey and the pineapple farmer interview to score each species on seven criteria and determine their overall suitability in the local context of Ruam Thai Village, Thailand.

| Category | Criteria | Score Descriptions | Score | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological | Elephant resilience | The two species that experienced the most elimination by elephants. | 1 | 2020 test plot data |

| The two species that experienced some elimination by elephants. | 2 | |||

| No elimination by elephants. | 3 | |||

| Environmental resilience | >30% of the crops in the sub-plot were eliminated due to environmental threats. | 1 | 2020 test plot data | |

| 10–30% of the crops in the sub-plot were eliminated due to environmental threats. | 2 | |||

| <10% of the crops in the sub-plot were eliminated due to environmental threats. | 3 | |||

| Crop health | <3 average health. | 1 | 2020 test plot data | |

| 3–4 average health. | 2 | |||

| 4 or higher average health. | 3 | |||

| Economic | Input requirements | Treatment is required to assist the crop’s growth and protect it from depredation. | 1 | 2020 test plot data, personal communication |

| Treatment is required to assist the crop’s growth or protect it from depredation. | 2 | |||

| Little or no treatment is required to assist the crop’s growth or protect it from depredation. | 3 | |||

| Profit potential | Did not produce yield by the end of the study period. | 1 | 2020 test plot data | |

| Produced yield, but overall, the sub-plot was not profitable by the end of the study period. | 2 | |||

| Produced yield, and overall, the sub-plot was profitable by the end of the study period. | 3 | |||

| Social | Labor investment | Requires weekly maintenance and treatment application. | 1 | 2020 test plot data, personal communication |

| Requires monthly maintenance and treatment application. | 2 | |||

| Requires maintenance and treatment application only a few times per year or not at all. | 3 | |||

| Local familiarity | Cultivated in household gardens, likely a few individual crops for personal use or consumption. | 1 | Household survey, pineapple farmer interview | |

| Cultivated at a commercial scale for sale to local shops and markets. | 2 | |||

| Cultivated at a commercial scale for sale to factories, agro-industrial buyers, etc. | 3 |

Appendix C

Table A3.

The proportions, sample sizes, and results from individual chi-square tests. Frequency of elephant visits and benefits from living nearby elephants were significantly (p =< 0.05) associated with interest in planting alternative crops to reduce crop damage and elephant presence in farms (household survey, Q.16).

Table A3.

The proportions, sample sizes, and results from individual chi-square tests. Frequency of elephant visits and benefits from living nearby elephants were significantly (p =< 0.05) associated with interest in planting alternative crops to reduce crop damage and elephant presence in farms (household survey, Q.16).

| Variables | Categories | Total (n = 239) | Not Interested (n = 119) | Interested (n = 120) | χ2 (p-Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elephant frequency | 1—Never | 8.4 (n = 20) | 7.9 (n = 19) | 0.4 (n = 1) | 23.1 (0.0003) |

| 2—Less than once per month | 27.2 (n = 65) | 15.1 (n = 36) | 12.1 (n = 29) | ||

| 3—Once per month | 18.8 (n = 45) | 8.8 (n = 21) | 10.0 (n = 24) | ||

| 4—Once per week | 19.2 (n = 46) | 7.1 (n = 17) | 12.1 (n = 29) | ||

| 5—Several times per week | 18.0 (n = 43) | 6.7 (n = 16) | 11.3 (n = 27) | ||

| 6—Every Night | 8.4 (n = 20) | 4.2 (n = 10) | 4.2 (n = 10) | ||

| Benefits from elephants | 0—No | 64.4 (n = 154) | 36.0 (n = 86) | 28.5 (n = 68) | 5.7 (0.0170) |

| 1—Yes | 35.6 (n = 85) | 13.8 (n = 33) | 21.8 (n = 52) | ||

| Total land (rai) | 1—(1–5) | 10.5 (n = 25) | 5.0 (n = 12) | 5.4 (n = 13) | 0.2 (0.9760) |

| 2—(6–10) | 43.1 (n = 103) | 22.2 (n = 53) | 20.9 (n = 50) | ||

| 3—(11–15) | 25.1 (n = 60) | 12.1 (n = 29) | 13.0 (n = 31) | ||

| 4 (>16) | 21.3 (n = 51) | 10.5 (n = 25) | 10.9 (n = 26) | ||

| Age | 1—(18–35) | 10.5 (n = 25) | 7.5 (n = 18) | 2.9 (n = 7) | 8.9 (0.0647) |

| 2—(36–45) | 25.1 (n = 60) | 13.0 (n = 31) | 12.1 (n = 29) | ||

| 3—(46–55) | 34.7 (n = 83) | 13.8 (n = 33) | 20.9 (n = 50) | ||

| 4—(56–65) | 21.8 (n = 52) | 10.9 (n = 26) | 10.9 (n = 26) | ||

| 5—(66+) | 7.9 (n = 19) | 4.6 (n = 11) | 3.3 (n = 8) | ||

| Gender | 0—Female | 43.5 (n = 104) | 21.8 (n = 52) | 21.8 (n = 52) | 0.0 (1.0000) |

| 1—Male | 56.5 (n = 135) | 28.0 (n = 67) | 28.5 (n = 68) |

Appendix D

Table A4.

The elimination by elephants and environmental threats recorded in each experimental species and pineapple in the 2020 test plot and the five 2021 test plots. Pineapple was fully eliminated by elephants in the 2020 test plot and two of the 2021 test plots (plots 2 and 5) by partial or full consumption, while elephants eliminated no more than 6.0% of any experimental crop species’ sub-plot by trampling.

Table A4.

The elimination by elephants and environmental threats recorded in each experimental species and pineapple in the 2020 test plot and the five 2021 test plots. Pineapple was fully eliminated by elephants in the 2020 test plot and two of the 2021 test plots (plots 2 and 5) by partial or full consumption, while elephants eliminated no more than 6.0% of any experimental crop species’ sub-plot by trampling.

| Species | Planted | Eliminated | Eliminated: Elephants | Eliminated: Environmental Threats | Total Eliminated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 test plot | |||||

| Pineapple | 400 | 400 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Mulberry | 112 | 59 | 1.8% | 50.9% | 52.7% |

| Kaffir lime | 58 | 26 | 5.2% | 39.7% | 44.8% |

| Lime | 24 | 7 | 0.0% | 29.2% | 29.2% |

| Chili | 295 | 66 | 4.4% | 18.0% | 22.4% |

| Karonda | 12 | 1 | 0.0% | 8.3% | 8.3% |

| Citronella | 300 | 16 | 0.7% | 4.7% | 5.3% |

| Lemongrass | 309 | 1 | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| 2021 test plot #1 | |||||

| Pineapple | 200 | 180 | 90.0% | 0.0% | 90.0% |

| Lemongrass | 200 | 2 | 1.8% | 2.4% | 4.2% |

| Citronella | 200 | 11 | 1.7% | 3.9% | 5.6% |

| 2021 test plot #2 | |||||

| Pineapple | 200 | 200 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Lemongrass | 200 | 2 | 0.0% | 1.0% | 1.0% |

| Citronella | 200 | 1 | 0.0% | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| 2021 test plot #3 | |||||

| Pineapple | 200 | 63 | 31.5% | 0.0% | 31.5% |

| Lemongrass | 200 | 16 | 6.0% | 2.0% | 8.0% |

| Citronella | 200 | 37 | 5.0% | 13.5% | 18.5% |

| 2021 test plot #4 | |||||

| Pineapple | 200 | 165 | 82.5% | 0.0% | 82.5% |

| Lemongrass | 200 | 10 | 2.0% | 3.0% | 5.0% |

| Citronella | 200 | 1 | 0.0% | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| 2021 test plot #5 | |||||

| Pineapple | 200 | 200 | 100.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% |

| Lemongrass | 200 | 12 | 1.0% | 5.0% | 6.0% |

| Citronella | 200 | 6 | 1.0% | 2.0% | 3.0% |

Appendix E

Table A5.

The frequency that elephants approached, entered and caused damage in the 2020 test plot and the five 2021 test plots. In the 2020 test plot, pineapple was eliminated 11 months into the 22-month study period. The frequency that elephants approached, entered and caused damage significantly decreased once pineapple was eliminated and only experimental crops remained.

Table A5.

The frequency that elephants approached, entered and caused damage in the 2020 test plot and the five 2021 test plots. In the 2020 test plot, pineapple was eliminated 11 months into the 22-month study period. The frequency that elephants approached, entered and caused damage significantly decreased once pineapple was eliminated and only experimental crops remained.

| Plot | Forest Edge (m) | Observation Nights | Approached | Approached (%) | Entered | Entered (%) | Caused Damage | Caused Damage (%) | Elephant Elimination: Pineapple | Elephant Elimination: Lemongrass | Elephant Elimination: Citronella |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 test plot: pineapple present | 20 | 263 | 108 | 41.1% | 51 | 19.4% | 22 | 8.4% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.7% |

| 2020 test plot: pineapple absent | 165 | 49 | 29.7% | 13 | 7.9% | 3 | 1.8% | NA | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| 2020 test plot: total | 428 | 157 | 36.7% | 64 | 15.0% | 25 | 5.8% | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.7% | |

| 2021: plot 1 | 55 | 365 | 115 | 31.5% | 43 | 11.8% | - | 90.0% | 1.8% | 1.7% | |

| 2021: plot 2 | 10 | 365 | 102 | 27.9% | 40 | 11.0% | - | 100.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| 2021: plot 3 | 10 | 365 | 121 | 33.2% | 26 | 7.1% | - | 31.5% | 6.0% | 5.0% | |

| 2021: plot 4 | 125 | 365 | 156 | 42.7% | 55 | 15.1% | - | 82.5% | 2.0% | 0.0% | |

| 2021: plot 5 | 10 | 365 | 163 | 44.7% | 69 | 18.9% | - | 100.0% | 1.0% | 1.0% |

References

- Menon, V.; Tiwari, S.K. Population status of Asian elephants Elephas maximus and key threats. Int. Zoo. Yearb. 2019, 53, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimgruber, P.; Gagnon, J.B.; Wemmer, C.; Kelly, D.S.; Songer, M.A.; Selig, E.R. Fragmentation of Asia’s remaining wildlands: Implications for Asian elephant conservation. Anim. Conserv. 2003, 6, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Silva, S.; Wu, T.; Nyhus, P.; Weaver, A.; Thieme, A.; Johnson, J.; Wadey, J.; Mossbrucker, A.; Vu, T.; Neang, T.; et al. Land-use change is associated with multi-century loss of elephant ecosystems in Asia. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalam, T.; Baishya, H.K.; Smith, D. Lethal fence electrocution: A major threat to Asian elephants in Assam, India. SAGE J. 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Water, A.; Matteson, K. Human-elephant conflict in western Thailand: Socio-economic drivers and potential mitigation strategies. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongtawan, T. Wild elephant-human conflicts in Thailand: The analysis from the media (2014–2018). In Proceedings of the KUVIC 2019 Conference, Huahin, Thailand, 13–14 June 2019; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C.; Tiwari, S.K.; Goswami, V.R.; de Silva, S.; Kumar, A.; Baskaran, N.; Yoganand, K.; Menon, V. Elephas maximus. IUCN Red List. Threat. Species 2020, T7140A45818198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, P.; Pastorini, J. Range-wide status of Asian elephants. Gajah 2011, 35, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, L.J.; Khadka, K.K.; Van Den Hoek, J.; Naithani, K.J. Human-elephant conflict: A review of current management strategies and future directions. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 6, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Water, A.; King, L.E.; Arkajak, R.; Arkajak, J.; van Doormaal, N.; Ceccarelli, V.; Sluiter, L.; Doornwaard, S.M.; Praet, V.; Owen, D.; et al. Beehive fences as a sustainable local solution to human-elephant conflict in Thailand. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2020, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, E.M.; Lahkar, B.P.; Subedi, N.; Nyirenda, V.R.; Lichtenfeld, L.L.; Jakoby, O. Does traditional and advanced guarding reduce crop losses due to wildlife? A comparative analysis from Africa and Asia. J. Nat. Conserv. 2019, 50, 125712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, M.W.; Kerley, G.I.H. Fencing for conservation: Restriction of evolutionary potential or a riposte to threatening processes? Bol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekor, A.; Miller, J.R.B.; Flyman, M.V.; Kasiki, S.; Kesch, M.K.; Miller, S.M.; Uiseb, K.; van der Merve, V.; Lindsey, P.A. Fencing Africa’s protected areas: Costs, benefits, and management issues. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 229, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochprapa, P.; Savini, C.; Ngoprasert, D.; Savini, T.; Gale, G.A. Spatio-temporal dynamics of human−elephant conflict in a valley of pineapple plantations. Integr. Conserv. 2023, 2, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitati, N.W.; Walpole, M.J. Assessing farm-based measures for mitigating human-elephant conflict in Transmara District, Kenya. Oryx 2006, 40, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, C.; Rodriguez, S.L.; Leimgruber, P.; Huang, Q.; Tonkyn, D. A quantitative assessment of the indirect impacts of human-elephant conflict. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiyo, P.I.; Cochrane, E.P.; Naughton, L.; Basuta, G.I. Temporal patterns of crop raiding by elephants: A response to changes in forage quality or crop availability? Afr. J. Ecol. 2005, 43, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, E.C.; Sereivathana, T.; Maltby, M.P.; Lee, P.C. Elephant crop-raiding and human-elephant conflict in Cambodia: Crop selection and seasonal timings of raids. Oryx 2011, 45, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmasuang, R.; Phumpakphan, N.; Deungkae, P.; Chaiyarat, R.; Pla-Ard, M.; Khiowsree, N.; Charaspet, K.; Paansrri, P.; Noowong, J. Review: Status of wild elephant, conflict and conservation actions in Thailand. Biodiversitas 2024, 25, 1479–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, J.W.K.; Jitvijak, S.; Saranet, S.; Buathong, S. Exploratory co-management interventions in Kuiburi National Park, Central Thailand, including human-elephant conflict mitigation. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 7, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiyo, P.I.; Lee, P.C.; Moss, C.J.; Archie, E.A.; Hollister-Smith, J.A.; Alberts, S.C. No risk, no gain: Effects of crop raiding and genetic diversity on body size in male elephants. Behav. Ecol. 2011, 22, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsika, T.A.; Adjetey, J.A.; Obopile, M.; Songhurst, A.C.; McCulloch, G.; Stronza, A. Alternative crops as a mitigation measure for elephant crop raiding in the eastern Okavango Panhandle. Pachyderm 2020, 61, 140–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. In the era of climate change: Moving beyond conventional agriculture in Thailand. Asian J. Agric. Dev. 2021, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, L.A.; Brye, K.R. Soil chemical property changes in response to long-term pineapple cultivation in Costa Rica. Agrosystems Geosci. Environ. 2019, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawatsin, A.; Thavara, U.; Siriyasatien, P. Pesticides used in Thailand and toxic effects to human health. Med. Res. Arch. 2015, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayo, F. Impacts of agricultural pesticides on terrestrial ecosystems. In Ecological Impacts of Toxic Chemicals; Sánchez-Bayo, F., van den Brink, P.J., Mann, R.M., Eds.; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2011; pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, E.M.; McRobb, R.; Gross, J. Cultivating alternative crops reduces crop losses due to African elephants. J. Pest Sci. 2016, 89, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, E.M.; Drouet-Hoguet, N.; Subedi, N.; Gross, J. The potential of medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs) to reduce crop damages by Asian Elephants (Elephas maximus). Crop Prot. 2017, 100, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, M.D.; Cook, R.M.; Bedetti, A.; Wilmot, J.; Roode, A.; Pereira, C.L.; Almeida, J.; Alverca, A. A phased approach to increase human tolerance in elephant corridors to link protected areas in southern Mozambique. Diversity 2023, 15, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.E.; Osborn, F.V. Investigating the potential for chilli (Capsicum annum) to reduce human-wildlife conflict in Zimbabwe. Oryx 2006, 40, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, E.M.; Lahkar, B.P.; Subedi, N.; Nyirenda, V.R.; Lichtenfeld, L.L.; Jakoby, O. Seasonality, crop type and crop phenology influence crop damage by wildlife herbivores in Africa and Asia. Biodivers. Conserv. 2018, 27, 2029–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, C.; Hung, V.; Anh, N.C.; Bao, H.D.; Quoc, P.D.; Khanh, H.T.; Van Minh, N.; Cam, N.T.; Cuong, C.D. A pilot study of cultivating non-preferred crops to mitigate human-elephant conflict in the buffer zone of Yok Don National Park, Vietnam. Gajah 2020, 51, 4–9. [Google Scholar]