Two New Species of Hymenogaster (Hymenogastraceae, Agaricales) from China Based on Morphological and Molecular Markers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Morphological Studies

2.2. DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, Sequencing and Nucleotide Alignment

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

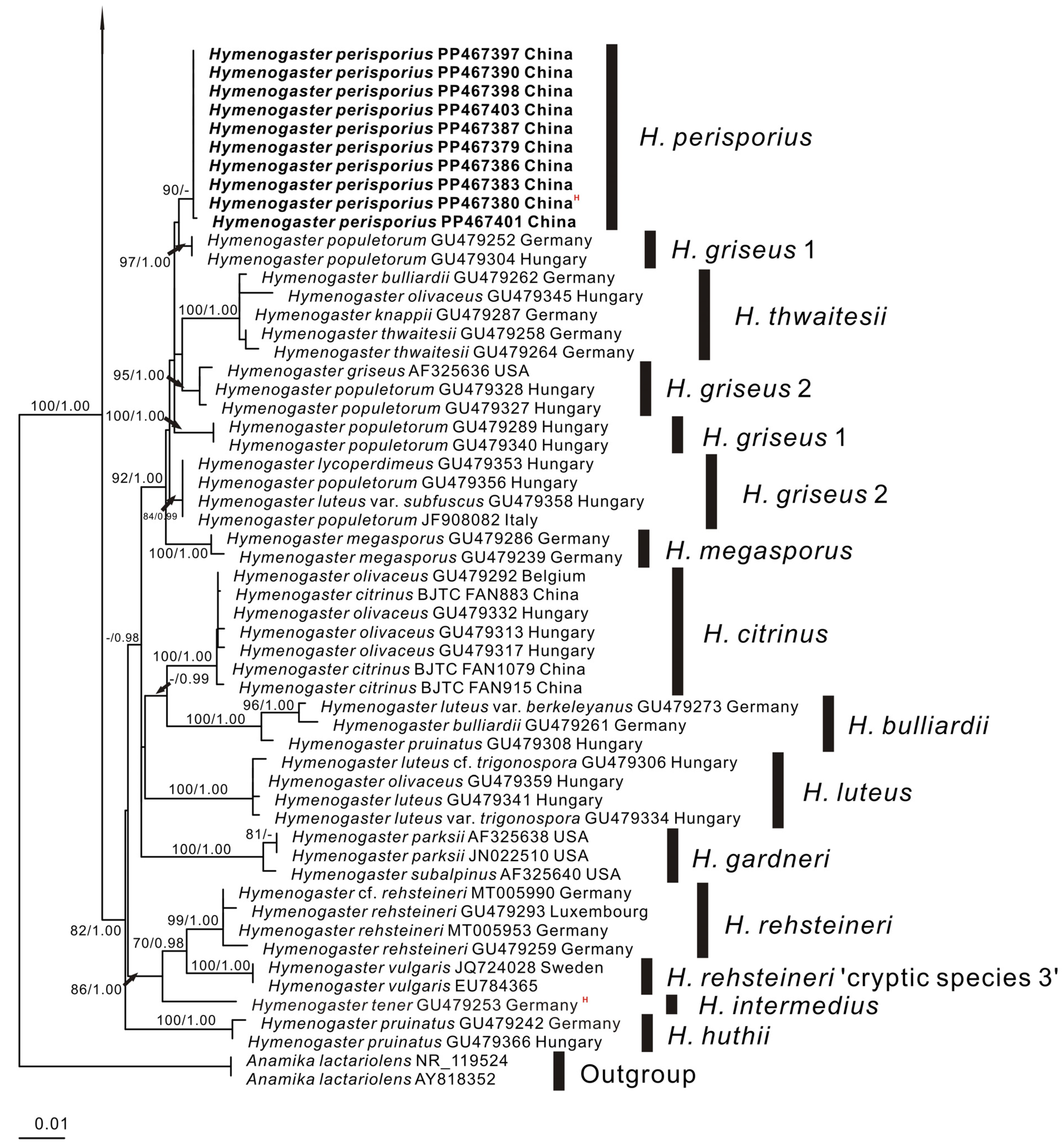

3.1. Molecular Phylogenetics

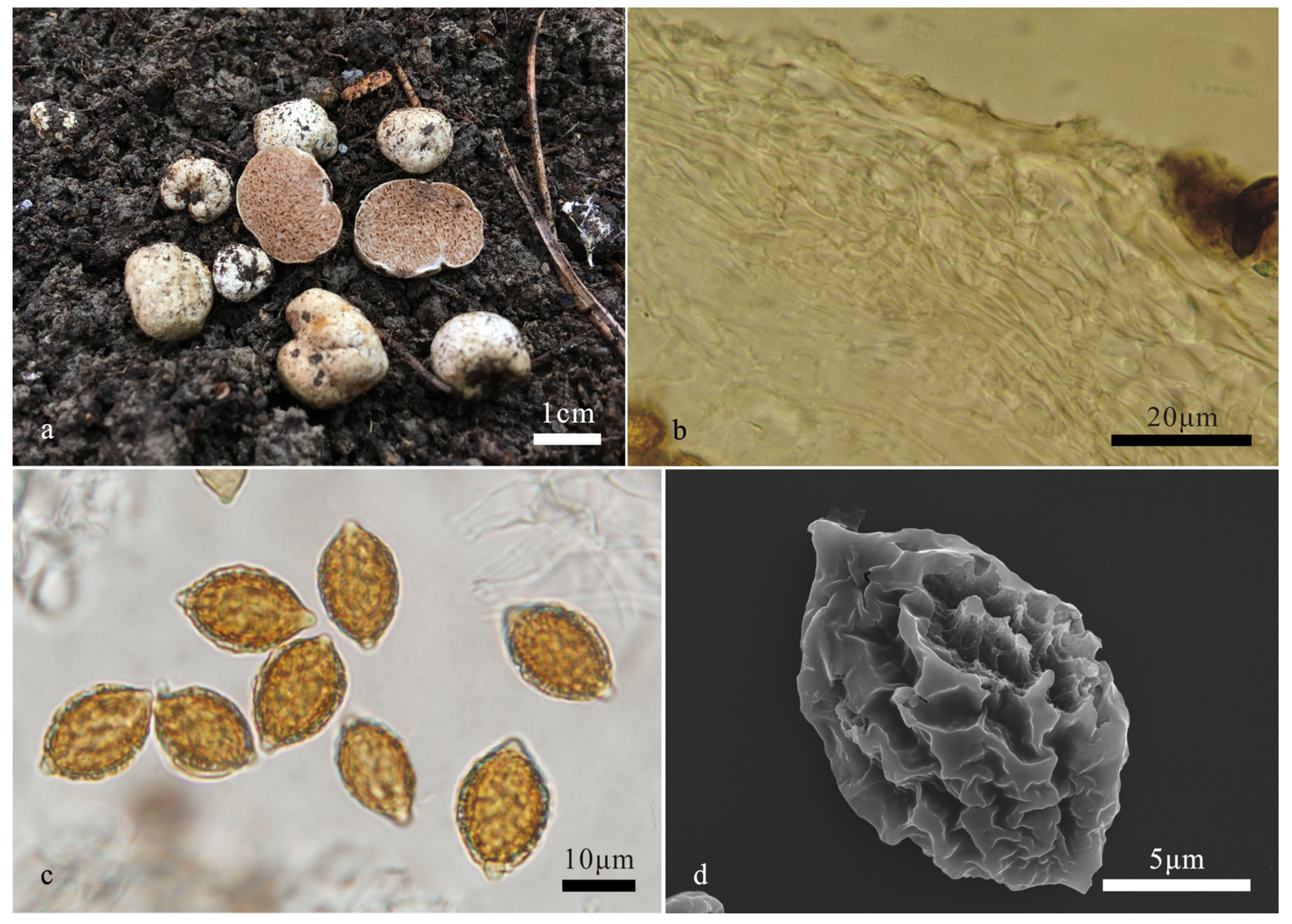

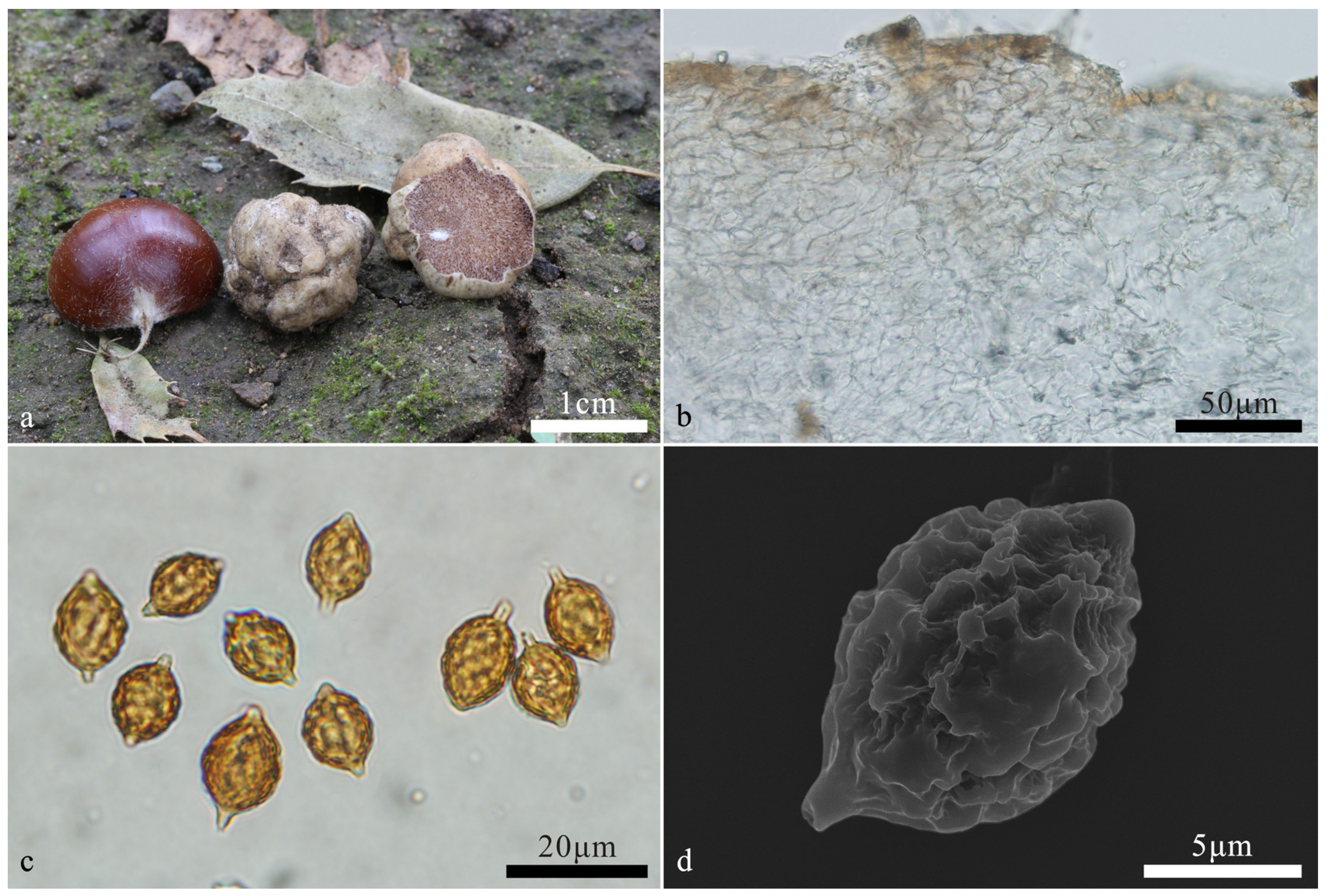

3.2. Taxonomy

4. Discussion

| 1. Basidiome pale yellow, white to dirty white when fresh | 2 |

| 1. Basidiome earth yellow to yellow brown when fresh | 6 |

| 2. Gleba reddish brown to brown when fresh | 3 |

| 2. Gleba light brown when fresh | H. minisporus |

| 3. Basidiospores length >17 μm | 4 |

| 3. Basidiospores length ≤17 μm | 5 |

| 4. Basidiospores 21–25.5 × 14–18.5 μm | H. citrinus |

| 4. Basidiospores 17–22 × 12–15 μm | H. perisporius |

| 5. Basidiospores 10–13.5 × 8–11.5 μm | H. zunhuaensis |

| 5. Basidiospores 13–17 × 10–13 μm | H. pseudoniveus |

| 6. Peridium exhibits substantial variation in thickness, differing by at least 120 μm | 7 |

| 6. Peridium exhibits substantial variation in thickness, differing by at the most 120 μm | 8 |

| 7. Basidiospores broad ellipsoidal to subglobose, Q = 1.1–1.3 | H. variabilis |

| 7. Basidiospores broad fusiform to broad citriform, Q = 1.3–1.4 | H. papilliformis |

| 8. Basidiospores fusiform, Q = 1.2–1.4 | H. arenarius |

| 8. Basidiospores broadly ellipsoidal to subglobose, Q = 1.1–1.3 | H. latisporus |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pegler, D.N.; Spooner, B.M.; Young, T.W.K. British truffles: A revision of British Hypogeous fungi. Kew Bull. 1993, 49, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Montecchi, A.; Sarasini, M. Funghi Ipogei d’Europa; AMB Fondazione Centro Studi Micologici: Vicenza, Italy, 2000; pp. 452–501. [Google Scholar]

- Pietras, M.; Rudawska, M.; Leski, T.; Karliński, L. Diversity of ectomycorrhizal fungus assemblages on nursery grown European beech seedlings. Ann. For. Sci. 2013, 70, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, V.N.; Perez, J.B. Contribution to the knowledge of hypogeous fungi in the Lyonnais area. Bull. Soc. Linn. Lyon 2018, 87, 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.E.; Schmull, M. Tropical truffles: English translation and critical review of F. von Höhnel’s truffles from Java. Mycol. Prog. 2011, 10, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkoğlu, A.; Castellano, M.A. New records of truffle fungi (Basidiomycetes) from Turkey. Turk. J. Bot. 2013, 37, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, W.C.; Couch, J.N. The Gasteromycetes of the Eastern United States and Canada, Republication of original 1928 version; Dover Publications Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1974; p. 201. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, R. Mycoflora Australis. Nova Hedwig. 1969, 29, 1–405. [Google Scholar]

- Beaton, G.; Pegler, D.N.; Young, T.W.K. Gasteroid Basidiomycotina of Victoria State, Australia. 3. Cortinariales. Kew Bull. 1985, 40, 167–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, M.A.; Trappe, J.M. Australasian truffle-like fungi. I. Nomenclatural bibliography of type descriptions of Basidiomycotina. Aust. Syst. Bot. 1990, 3, 653–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halling, R.E. Thaxter’s Thaxterogasters and other Chilean hypogeous fungi. Mycologia 1981, 73, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, M.A.; Verbeken, A.; Walleyn, R.; Thoen, D. Some new or interesting sequestrate Basidiomycota from African woodlands. Karstenia 2000, 40, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Liu, Y.H.; Liu, J.H. Hypogeous fungi in China. Edible Fungi China 2002, 21, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Mao, N.; Fu, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Fan, L. Five new species of the Genus Hymenogaster (Hymenogastraceae, Agaricales) from Northern China. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harkness, H.W. Californian hypogaeous fungi. Calif. Acad. Sci. 1899, 1, 241–291. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.H. Notes on Dendrogaster, Gymnoglossum, Protoglossum and species of Hymenogaster. Mycologia 1966, 58, 100–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cázares, E.; Trappe, J.M. Alpine and subalpine fungi of the Cascade Mountains. I. Hymenogaster glacialis sp. nov. Mycotaxon 1990, 38, 245–249. [Google Scholar]

- Fogel, R.; States, J. Materials for a hypogeous mycoflora of the Great Basin and adjacent cordilleras of the western United States VI: Hymenogaster rubyensis sp. nov. (Basidiomycota, Cortinariaceae). Mycotaxon 2001, 80, 333–337. [Google Scholar]

- Julou, T.; Burghardt, B.; Gebauer, G.; Berveiller, D.; Damesin, C.; Selosse, M.A. Mixotrophy in orchids: Insights from a comparative study of green individuals and nonphotosynthetic individuals of Cephalantera damasonium. New Phytol. 2005, 166, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trappe, J.M.; Molina, R.; Luoma, D.L.; Cázares, E.; Pilz, D.; Smith, J.E.; Castellano, M.A.; Miller, S.L.; Trappe, J.M. Diversity, Ecology, and Conservation of Truffle Fungi in Forests of the Pacific Northwest; Pacific Northwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2009; pp. 1–194.

- Pecoraro, L.; Huang, L.; Caruso, T.; Perotto, S.; Girlandam, M.; Cai, L.; Liu, Z.J. Fungal diversity and specificity in Cephalanthera damasonium and C. longifolia (Orchidaceae) mycorrhizas. J. Syst. Evol. 2017, 55, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudawska, M.; Kujawska, M.; Leski, T.; Janowski, D.; Karliński, L.; Wilgan, R. Ectomycorrhizal community structure of the admixture tree species Betula pendula, Carpinus betulus, and Tilia cordata grown in bare-root forest nurseries. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 437, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teron, J.N.; Hutchison, L.J. Consumption of truffles and other fungi by the American Red Squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) and the Eastern Chipmunk (Tamias striatus) (Sciuridae) in northwestern Ontario. Can. Field-Nat. 2013, 127, 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.T.; Weir, A.; Horton, T.R. Small mammal consumption of hypogeous fungi in the central Adirondacks of New York. Northeast. Nat. 2015, 22, 648–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuske, S.J.; Vernes, K.; May, T.W.; Claridge, A.W.; Congdon, B.C.; Krockenberger, A.; Abell, S.E. Data on the fungal species consumed by mammal species in Australia. Data Brief 2017, 12, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komur, P.; Chachuła, P.; Kapusta, J.; Wierzbowska, I.A.; Rola, K.; Olejniczak, P.; Mleczko, P. What determines species composition and diversity of hypogeous fungi in the diet of small mammals? A comparison across mammal species, habitat types and seasons in central European mountains. Fungal Ecol. 2020, 50, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.Q.; Zhao, R.L.; Hyde, K.D.; Begerow, D.; Kemler, M.; Yurkov, A.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Raspé, O.; Kakishima, M.; Sánchez-Ramírez, S.; et al. Notes, outline and divergence times of Basidiomycota. Fungal Divers. 2019, 99, 105–367. [Google Scholar]

- Dring, D.M. Techniques for microscopic preparation. In Methods in Microbiology; Booth, C., Ed.; Academic Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1971; pp. 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- Gardes, M.; Bruns, T.D. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for Basidiomycetes—Application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 1993, 2, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols, A Guide to Methods and Applications; Seliger, H., Gelfand, D.H., Sinsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys, R.; Hester, M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Frith, M.C. Adding unaligned sequences into an existing alignment using MAFFT and LAST. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 3144–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A. Estimating the rate of molecular evolution: Incorporating non-contemporaneous sequences into maximum likelihood phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2000, 16, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A.; Ludwig, T.; Meier, H. RAxML-III: A fast program for maximum likelihood-based inference of large phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML-VI-HPC: Maximum likelihood based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 2688–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nylander, J. MrModeltest, Version 2.2. Computer Software distributed by the University of Uppsala. Evolutionary Biology Centre: Uppsala, Sweden, 2004.

- Page, R.D.M. TreeView; Glasgow University: Glasgow, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis, D.M.; Bull, J.J. An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Syst. Biol. 1993, 42, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, F.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 1572–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaro, M.E.; Zoller, S.; Lutzoni, F. Bayes or bootstrap? A simulation study comparing the performance of Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling and bootstrapping in assessing phylogenetic confidence. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003, 20, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. Flore fungorum sinicorum Vol. 7. Hymenogastrales, Melanogastrales and Gautieriales; Science and Technology of China Press: Beijing, China, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, C.W.; Zeller, S.M. Hymenogaster and related genera. Ann. Mo. Gard. 1934, 21, 625–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Taxon Name in Analysis | Taxon Name | Collection | Country | GenBank Accession Number | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | nrLSU | ||||

| Anamika lactariolens AY818352 | Anamika lactariolens | taxon:301353 | AY818352 | - | |

| Anamika lactariolens NR_119524 | Anamika lactariolens | HC 88/95 | NR_119524 | - | |

| Hymenogaster arenarius BJTC FAN786 China | Hymenogaster arenarius | BJTC FAN786 | China | PP467413 | PP467449 |

| Hymenogaster arenarius BJTC FAN856 China | Hymenogaster arenarius | BJTC FAN856 | China | PP467414 | PP467450 |

| Hymenogaster arenarius GU479233 Germany | Hymenogaster arenarius | it10_26_2 | Germany | GU479233 | - |

| Hymenogaster arenarius GU479272 Germany | Hymenogaster arenarius | it5_2 | Germany | GU479272 | - |

| Hymenogaster arenarius GU479278 Germany | Hymenogaster arenarius | it6_3 | Germany | GU479278 | - |

| Hymenogaster bulliardii GU479261 Germany | Hymenogaster bulliardii | it20_4 | Germany | GU479261 | - |

| Hymenogaster bulliardii GU479262 Germany | Hymenogaster thwaitesii | it20_4_1 | Germany | GU479262 | - |

| Hymenogaster cf. niveus MT005942 Germany | Hymenogaster xxx | KR-M-0044217 | Germany | MT005942 | - |

| Hymenogaster cf. niveus MT005967 Germany | Hymenogaster niveus c ‘ryptic species 3’ | KR-M-0044314 | Germany | MT005967 | - |

| Hymenogaster cf. rehsteineri MT005990 Germany | Hymenogaster rehsteineri | KR-M-0044423 | Germany | MT005990 | - |

| Hymenogaster citrinus BJTC FAN1079 China | Hymenogaster citrinus | BJTC FAN1079 | China | PP467412 | PP467448 |

| Hymenogaster citrinus BJTC FAN883 China | Hymenogaster citrinus | BJTC FAN883 | China | PP467410 | PP467446 |

| Hymenogaster citrinus BJTC FAN915 China | Hymenogaster citrinus | BJTC FAN915 | China | PP467411 | PP467447 |

| Hymenogaster glacialis AF325634 | Hymenogaster sp. | GP 5302 | - | AF325634 | - |

| Hymenogaster griseus AF325636 USA | Hymenogaster griseus 2 | Trappe 12841 | USA | AF325636 | - |

| Hymenogaster knappii GU479287 Germany | Hymenogaster thwaitesii | it9_2 | Germany | GU479287 | - |

| Hymenogaster latisporus BJTC FAN1134 China | Hymenogaster latisporus | BJTC FAN1134, holotype | China | PP467404 | PP467440 |

| Hymenogaster luteus cf. trigonospora GU479306 Hungary | Hymenogaster luteus | zb1457 | Hungary | GU479306 | - |

| Hymenogaster luteus GU479341 Hungary | Hymenogaster luteus | zb2603 | Hungary | GU479341 | - |

| Hymenogaster luteus var. berkeleyanus GU479273 Germany | Hymenogaster bulliardii | it5_21 | Germany | GU479273 | - |

| Hymenogaster luteus var. subfuscus GU479358 Hungary | Hymenogaster griseus 2 | zb37 | Hungary | GU479358 | - |

| Hymenogaster luteus var. trigonospora GU479334 Hungary | Hymenogaster luteus | zb235 | Hungary | GU479334 | - |

| Hymenogaster lycoperdineus GU479353 Hungary | Hymenogaster griseus 2 | zb3533 | Hungary | GU479353 | - |

| Hymenogaster megasporus GU479239 Germany | Hymenogaster megasporus | it12_1 | Germany | GU479239 | - |

| Hymenogaster megasporus GU479286 Germany | Hymenogaster megasporus | it8_5_1 | Germany | GU479286 | - |

| Hymenogaster minisporus BJTC FAN1244 China | Hymenogaster minisporus | BJTC FAN1244, holotype | China | PP467407 | PP467443 |

| Hymenogaster niveus GU479255 Germany | Hymenogaster niveus c ‘ryptic species 1’ | it17_3 | Germany | GU479255 | - |

| Hymenogaster niveus GU479307 Hungary | Hymenogaster xxx | zb1461 | Hungary | GU479307 | - |

| Hymenogaster niveus GU479344 Hungary | Hymenogaster niveus c ‘ryptic species 3’ | zb28 | Hungary | GU479344 | - |

| Hymenogaster niveus KU878613 USA | Hymenogaster xxx | SC14_3 | USA | KU878613 | - |

| Hymenogaster olivaceus GU479292 Belgium | Hymenogaster citrinus | dt8293 | Belgium | GU479292 | - |

| Hymenogaster olivaceus GU479313 Hungary | Hymenogaster citrinus | zb1645 | Hungary | GU479313 | - |

| Hymenogaster olivaceus GU479317 Hungary | Hymenogaster citrinus | zb1817 | Hungary | GU479317 | - |

| Hymenogaster olivaceus GU479332 Hungary | Hymenogaster citrinus | zb2300 | Hungary | GU479332 | - |

| Hymenogaster olivaceus GU479345 Hungary | Hymenogaster thwaitesii | zb2804 | Hungary | GU479345 | - |

| Hymenogaster olivaceus GU479359 Hungary | Hymenogaster luteus | zb3721 | Hungary | GU479359 | - |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN1002 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN1002 | China | PP467396 | PP467432 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN1070 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN1070 | China | PP467399 | PP467435 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN1074 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN1074, holotype | China | PP467400 | PP467436 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN1109 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN1109 | China | PP467402 | PP467438 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN1156 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN1156 | China | PP467406 | PP467442 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN1266 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN1266 | China | PP467408 | PP467444 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN1267 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN1267 | China | PP467409 | PP467445 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN655 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN655 | China | PP467381 | PP467417 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN807 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN807 | China | PP467384 | PP467420 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN820 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN820 | China | PP467385 | PP467421 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN891 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN891 | China | PP467388 | PP467424 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN944 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN944 | China | PP467389 | PP467425 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN958 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN958 | China | PP467391 | PP467427 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN960 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN960 | China | PP467392 | PP467428 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN980 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN980 | China | PP467393 | PP467429 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN983 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN983 | China | PP467394 | PP467430 |

| Hymenogaster papilliformis BJTC FAN992 China | Hymenogaster papilliformis | BJTC FAN992 | China | PP467395 | PP467431 |

| Hymenogaster parksii AF325638 USA | Hymenogaster gardneri | Trappe 13296 | USA | AF325638 | - |

| Hymenogaster parksii JN022510 USA | Hymenogaster gardneri | SOC1643 | USA | JN022510 | - |

| Hymenogaster perisporius BJTC FAN1038 China | Hymenogaster perisporius | BJTC FAN1038 | China | PP467397 | PP467433 |

| Hymenogaster perisporius BJTC FAN1049 China | Hymenogaster perisporius | BJTC FAN1049 | China | PP467398 | PP467434 |

| Hymenogaster perisporius BJTC FAN1076 China | Hymenogaster perisporius | BJTC FAN1076 | China | PP467401 | PP467437 |

| Hymenogaster perisporius BJTC FAN1126 China | Hymenogaster perisporius | BJTC FAN1126 | China | PP467403 | PP467439 |

| Hymenogaster perisporius BJTC FAN606 China | Hymenogaster perisporius | BJTC FAN606 | China | PP467379 | PP467415 |

| Hymenogaster perisporius BJTC FAN651 China | Hymenogaster perisporius | BJTC FAN651, holotype | China | PP467380 | PP467416 |

| Hymenogaster perisporius BJTC FAN768 China | Hymenogaster perisporius | BJTC FAN768 | China | PP467383 | PP467419 |

| Hymenogaster perisporius BJTC FAN846 China | Hymenogaster perisporius | BJTC FAN846 | China | PP467386 | PP467422 |

| Hymenogaster perisporius BJTC FAN850 China | Hymenogaster perisporius | BJTC FAN850 | China | PP467387 | PP467423 |

| Hymenogaster perisporius BJTC FAN952 China | Hymenogaster perisporius | BJTC FAN952 | China | PP467390 | PP467426 |

| Hymenogaster populetorum GU479252 Germany | Hymenogaster griseus 1 | it16_1_1 | Germany | GU479252 | - |

| Hymenogaster populetorum GU479289 Hungary | Hymenogaster griseus 1 | aszodvt_1991 | Hungary | GU479289 | - |

| Hymenogaster populetorum GU479304 Hungary | Hymenogaster griseus 1 | zb1436 | Hungary | GU479304 | - |

| Hymenogaster populetorum GU479327 Hungary | Hymenogaster griseus 2 | zb2097 | Hungary | GU479327 | - |

| Hymenogaster populetorum GU479328 Hungary | Hymenogaster griseus 2 | zb2105 | Hungary | GU479328 | - |

| Hymenogaster populetorum GU479340 Hungary | Hymenogaster griseus 1 | zb2576 | Hungary | GU479340 | - |

| Hymenogaster populetorum GU479356 Hungary | Hymenogaster griseus 2 | zb3594 | Hungary | GU479356 | - |

| Hymenogaster populetorum JF908082 Italy | Hymenogaster griseus 2 | 17022 | Italy | JF908082 | - |

| Hymenogaster pruinatus GU479242 Germany | Hymenogaster huthii | it12_3_1 | Germany | GU479242 | - |

| Hymenogaster pruinatus GU479308 Hungary | Hymenogaster bulliardii | zb1485 | Hungary | GU479308 | - |

| Hymenogaster pruinatus GU479366 Hungary | Hymenogaster huthii | zb95 | Hungary | GU479366 | - |

| Hymenogaster pseudoniveus BJTC FAN874 China | Hymenogaster pseudoniveus | BJTC FAN874 | China | PP622380 | PP622367 |

| Hymenogaster pseudoniveus BJTC FAN916 China | Hymenogaster pseudoniveus | BJTC FAN916 | China | PP622383 | PP622370 |

| Hymenogaster pseudoniveus BJTC FAN967 China | Hymenogaster pseudoniveus | BJTC FAN967 | China | PP622382 | PP622369 |

| Hymenogaster pseudoniveus BJTC FAN1069 China | Hymenogaster pseudoniveus | BJTC FAN1069 | China | PP622379 | PP622366 |

| Hymenogaster pseudoniveus BJTC FAN1075 China | Hymenogaster pseudoniveus | BJTC FAN1075, holotype | China | PP622378 | PP622365 |

| Hymenogaster pseudoniveus BJTC FAN1238 China | Hymenogaster pseudoniveus | BJTC FAN1238 | China | PP622384 | - |

| Hymenogaster pseudoniveus BJTC FAN1251 China | Hymenogaster pseudoniveus | BJTC FAN1251 | China | PP622381 | PP622368 |

| Hymenogaster rehsteineri GU479259 Germany | Hymenogaster rehsteineri | it2_4_1 | Germany | GU479259 | - |

| Hymenogaster rehsteineri GU479293 Luxembourg | Hymenogaster rehsteineri | dt8455 | Luxembourg | GU479293 | - |

| Hymenogaster rehsteineri MT005953 Germany | Hymenogaster rehsteineri | KR-M-0044018 | Germany | MT005953 | - |

| Hymenogaster rubyensis AY945303 USA | Hymenogaster sp. | Fogel 2698 | USA | AY945303 | - |

| Hymenogaster sp. MK027200 Slovenia | Hymenogaster niveus c ‘ryptic species 1’ | FV4_04 | Slovenia | MK027200 | - |

| Hymenogaster subalpinus AF325640 USA | Hymenogaster gardneri | Trappe 22752 | USA | AF325640 | - |

| Hymenogaster tener EU784363 UK | Hymenogaster tener | RBG Kew K(M)102406 | UK | EU784363 | - |

| Hymenogaster tener GU479250 Germany | Hymenogaster tener | it15_3 | Germany | GU479250 | - |

| Hymenogaster tener GU479253 Germany | Hymenogaster intermedius | it16_2, holotype | Germany | GU479253 | - |

| Hymenogaster thwaitesii GU479258 Germany | Hymenogaster thwaitesii | it2_2 | Germany | GU479258 | - |

| Hymenogaster thwaitesii GU479264 Germany | Hymenogaster thwaitesii | it3_2 | Germany | GU479264 | - |

| Hymenogaster variabilis BJTC FAN1141 China | Hymenogaster variabilis | BJTC FAN1141 | China | PP467405 | PP467441 |

| Hymenogaster variabilis BJTC FAN656 China | Hymenogaster variabilis | BJTC FAN656, holotype | China | PP467382 | PP467418 |

| Hymenogaster vulgaris EU784365 | Hymenogaster rehsteineri c ‘ryptic species 3’ | RBG Kew K(M)27363 | - | EU784365 | - |

| Hymenogaster vulgaris JQ724028 Sweden | Hymenogaster rehsteineri c ‘ryptic species 3’ | GN_4d_I | Sweden | JQ724028 | - |

| Hymenogaster zunhuaensis BJTC FAN1061 China | Hymenogaster zunhuaensis | BJTC FAN1061 | China | PP622373 | PP622361 |

| Hymenogaster zunhuaensis BJTC FAN1062 China | Hymenogaster zunhuaensis | BJTC FAN1062, holotype | China | PP622376 | PP622363 |

| Hymenogaster zunhuaensis BJTC FAN1083 China | Hymenogaster zunhuaensis | BJTC FAN1083 | China | PP622374 | PP622362 |

| Hymenogaster zunhuaensis BJTC FAN1105 China | Hymenogaster zunhuaensis | BJTC FAN1105 | China | PP622372 | PP622360 |

| Hymenogaster zunhuaensis BJTC FAN1162 China | Hymenogaster zunhuaensis | BJTC FAN1162 | China | PP622375 | - |

| Hymenogaster zunhuaensis BJTC FAN1249 China | Hymenogaster zunhuaensis | BJTC FAN1249 | China | PP622377 | PP622364 |

| Hymenogaster zunhuaensis BJTC FAN1259 China | Hymenogaster zunhuaensis | BJTC FAN1259 | China | PP622371 | PP622359 |

| Uncultured Agaricales HM105539 China | Hymenogaster minisporus | QL054 | China | HM105539 | - |

| Uncultured fungus EU554705 Canada | Hymenogaster sp. | A2N_88 | Canada | EU554705 | - |

| Uncultured fungus EU554717 Canada | Hymenogaster sp. | A3E_60 | Canada | EU554717 | - |

| Uncultured Hymenogaster LT980461 China | Hymenogaster minisporus | taxon:522720 | China | LT980461 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, T.; Mao, N.; Fu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, L. Two New Species of Hymenogaster (Hymenogastraceae, Agaricales) from China Based on Morphological and Molecular Markers. Diversity 2024, 16, 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16050303

Li T, Mao N, Fu H, Zhang Y, Fan L. Two New Species of Hymenogaster (Hymenogastraceae, Agaricales) from China Based on Morphological and Molecular Markers. Diversity. 2024; 16(5):303. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16050303

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ting, Ning Mao, Haoyu Fu, Yuxin Zhang, and Li Fan. 2024. "Two New Species of Hymenogaster (Hymenogastraceae, Agaricales) from China Based on Morphological and Molecular Markers" Diversity 16, no. 5: 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16050303

APA StyleLi, T., Mao, N., Fu, H., Zhang, Y., & Fan, L. (2024). Two New Species of Hymenogaster (Hymenogastraceae, Agaricales) from China Based on Morphological and Molecular Markers. Diversity, 16(5), 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16050303