Abstract

Diatoms are among the most common epibionts and have been recorded on the surfaces of various living substrates, either plants or animals. However, studies on them are still scarce in view of the many substrata available. In this study, epibiotic diatoms living on Callinectes bellicosus were identified for the first time from a subtropical coastal lagoon in Northwest Mexico. We tested the null hypothesis that the diatom flora living on the carapaces of C. bellicosus would not be similar to that recorded for mangrove sediments, its typical habitat. The epibiotic diatoms were brushed off from the carapaces of two specimens, acid-cleaned, mounted in synthetic resin, and identified based on frustule morphology. This way, 106 taxa from 46 genera were recorded, including 25 singletons, and 6 new records for the Mexican northwest region. The best-represented genera were Nitzschia (10 taxa), Mastogloia (9), Diploneis (8), Navicula (7), Amphora (5), Cocconeis (5), Tryblionella (4), and Gyrosigma (4). Species composition included 93% of local taxa, thus refuting the proposed hypothesis and supporting the alternate one. Although the estimated species richness was lower than that in sediments, it deems the green crab carapace a favorable substrate for the growth of benthic diatoms.

1. Introduction

The interaction between an organism (basibiont) and those that live on it (epibionts) is known as epibiosis. This type of relationship has been documented as a common phenomenon in aquatic ecosystems, especially in marine environments [1], and the phenomenon of adhesion of microalgae (including diatoms) to living substrata is well studied [2]. Diatoms represent a principal constituent of microphytobenthos, and a common habitat of theirs is living substrata, sometimes plants and algae (epiphytic diatoms) and other times animals (epizoic diatoms) [2,3]. In this vein, the importance of the epizoic growth of diatoms has been described for many types of hosts, including insects, turtles, diving birds, marine mammals [4,5,6,7,8,9], and crustaceans, such as amphipoda, cladocerans, copepods, decapods, and hoplocarids [10,11,12,13,14]. Studies on crabs’ epibiota have focused on the macro-epibionts, seeking to elucidate their masking behavior [1,15]. In the Gulf of California, the type and quantity of pieces used by decorator crabs (Majidae) was studied [16], observing the dominance of macroalgae and sponges. Others have focused on the adherence capability of epibionts such as diatoms. However, little was hitherto known about the species composition, seasonality, or types of habitats in which epizoic diatoms occur on green swimming crabs in any area. Moreover, further ecological research on the interactive relations between epibiotic diatoms and their basibionts requires basic floristic information in order to carry out formal biodiversity or ecological studies related to the consequences of using animal surfaces as substrates by benthic diatoms. Given the challenge that this presents, in general, there is scarce information on diatom epibiosis with crabs [17,18], in that the species composition and richness of epibiotic diatoms have received very little attention.

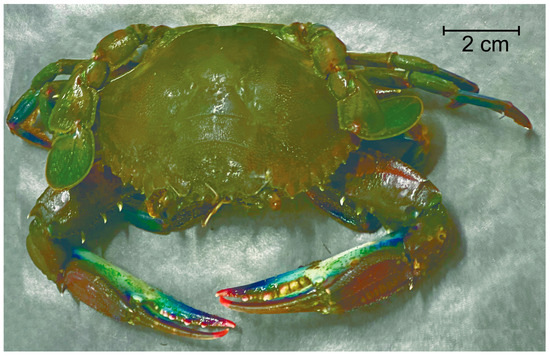

The green swimming crab Callinectes bellicosus Stimpson 1859 (Decapoda: Portunidae) is distributed along the Eastern Pacific, ranging from California, USA, to the Tehuantepec Gulf, Oaxaca, Mexico. It inhabits estuaries, coastal lagoons, and soft bottoms up to 90 m deep [19,20], and adults can live for 3–4 years [19,21]. The species is omnivorous, and it is an opportunistic predator, often burrowing down superficially in the sediments to wait for its prey [22]. This behavior makes green swimming crabs not only accessible but suitable as a substrate for a variety of small marine biota, which they may carry on their carapaces, such as various algal forms [23,24], including benthic diatoms. However, up to now, the species composition of epibiotic diatoms of green swimming crabs has remained unexplored. Thus, it is unknown how many diatom species or forms may be found that are either truly epizoic or just opportunistic, and the differential benefits that these may have in terms of survival, reproduction, or dispersal also have yet to be revealed. The basic floristics of epibiotic diatoms will surely provide a reliable platform to undertake further ecological studies between them and this basibiont.

According to the above, in the present study, the epibiotic diatom flora living on carapaces of C. bellicosus from the subtropical coastal lagoon of La Paz, BCS, Mexico, was investigated. The relevant background on this flora shows that the benthic diatom flora from the northwest region of Mexico has been previously studied in several localities including mangrove environments [25]. In these and later investigations around 1500, benthic diatom taxa were recorded, providing a reliable reference for our work. Moreover, the structure of the benthic diatom assemblages has been described based on the characteristic taxa in such a way that a typical benthic diatom flora can be recognized for the region. Thus, considering the observed distribution of the benthic diatom taxa on the various substrates inspected in said works, we asked if the diatom flora living on the carapaces of green swimming crabs would be similar to that recorded for mangrove sediments, its typical habitat in the northwest region of Mexico. Thus, we tested the null hypothesis that the diatom flora living on the carapaces of green swimming crabs would not be similar to that recorded historically for the mangrove sediments in the southern Baja California Peninsula (northwest region of Mexico). This abduction (Ho) responds to the influence of the mobility of the basibiont and constant exposure of the colonized surface, plus discrete temporal sampling, which could exhibit a seasonal variation in the species composition of the colonizing diatoms, that may result in a difference in species composition between the typical diatom flora and that living on the inspected green crab specimens.

2. Materials and Methods

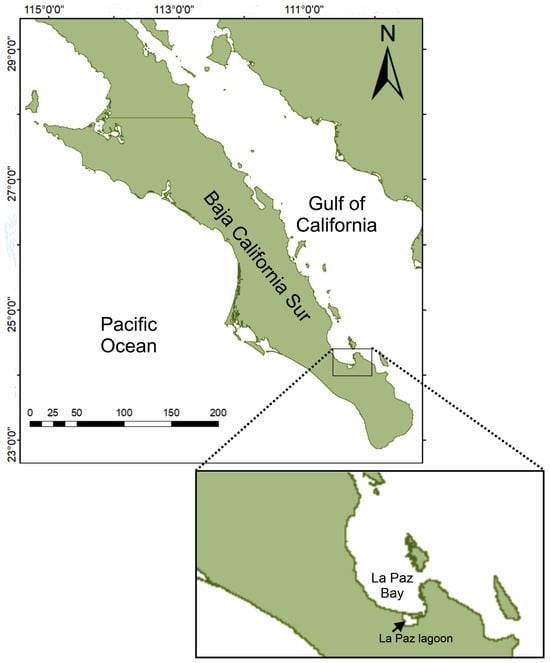

The La Paz coastal lagoon forms part of La Paz Bay, a shallow-bottom water body that reaches 10 m deep with a dominant soft bottom. In the northwest part of the lagoon, the mangrove swamp of Zacatecas Estuary is located (24°10′27″ N, 110°26′ 06″ W) (Figure 1). There, in September 2022, two male specimens of C. bellicosus (Figure 2) were captured using a hand net and identified according to [20].

Figure 1.

Sampling site where two green swimming crabs were captured in the La Paz coastal lagoon, southeast of Bahia de La Paz, Mexico.

Figure 2.

Captured specimen of green swimming crab (Callinectes bellicosus) at Estero Zacatecas, La Paz lagoon, B.C.S., Mexico, from which the identified epibiotic diatoms were sampled.

Diatoms were separated from the cephalothoraxes and chelae of the swimming crabs using a toothbrush to generate a compound sample of the two specimens. The brushed-off material was placed in a 250 mL flask and preserved in commercial 70% ethanol. Afterward, to eliminate organic matter that would obstruct the visibility of the diatom frustules, the compound sample was oxidized by adding 3 mL of 70% nitric acid to 2 mL of sample and then heating the mixture with a burner to the boiling point, where it was held until the emission of gas subsided, indicating the end of the reaction (ca. 3 min). The oxidized sample was rinsed repeatedly with deionized water until it reached a circumneutral pH. Then, six mounted slides were inspected under a Zeiss® Axio Lab A1 (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) compound microscope equipped with phase contrast and a Canon 5D Mark II camera (Canon, Tokyo, Japan). Diatoms were identified based on frustule morphology using classic and recent references [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45].

A systematic list of the diatom taxa was constructed following practical formats [46,47,48,49]. Nomenclatural updates for the identified taxa were performed based on www.algaebase.org [50] and www.marinespecies.org (accessed on 1 December 2023) [51]. This was complemented by an iconographic catalog of all the recorded taxa.

3. Results

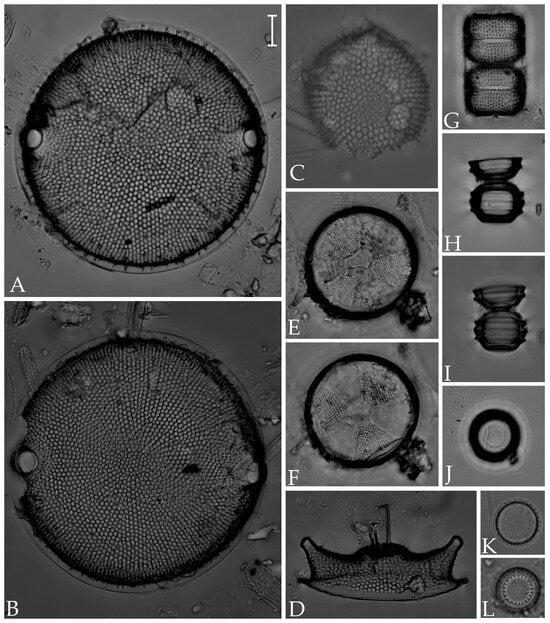

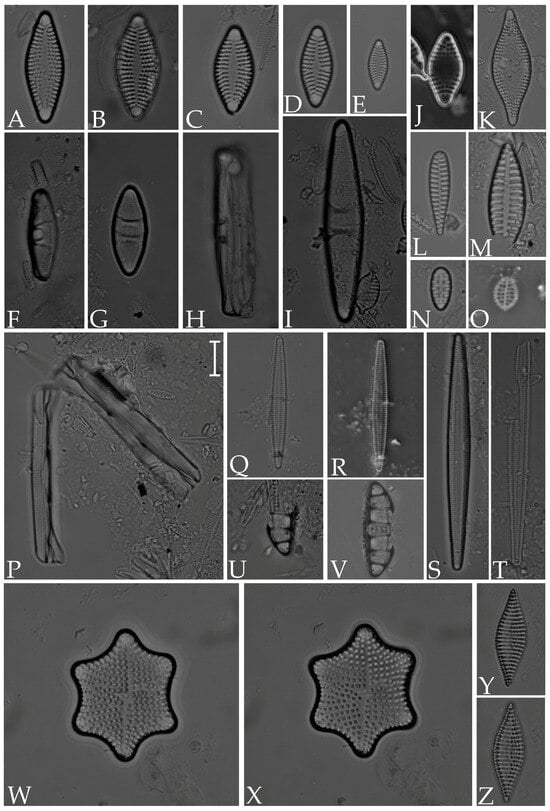

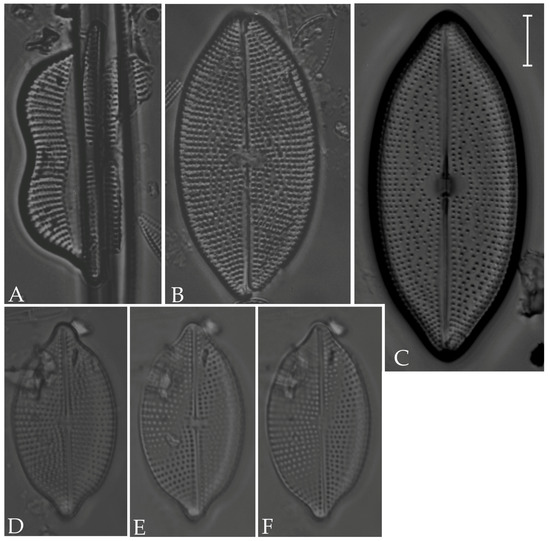

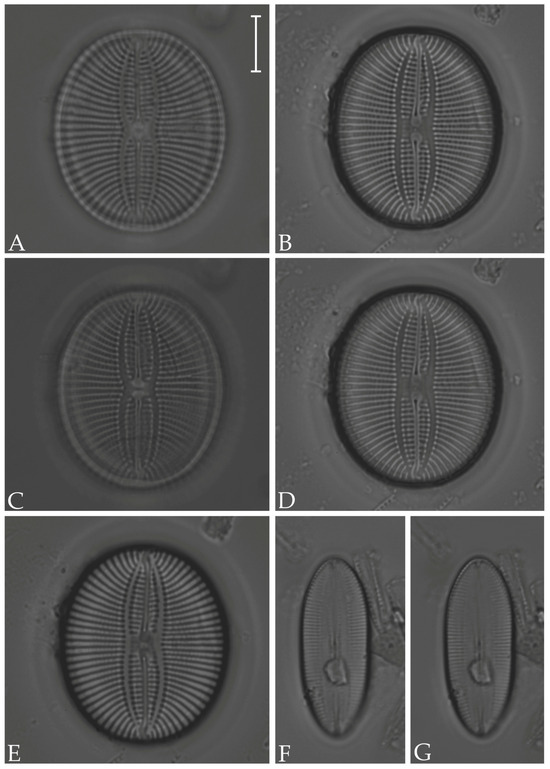

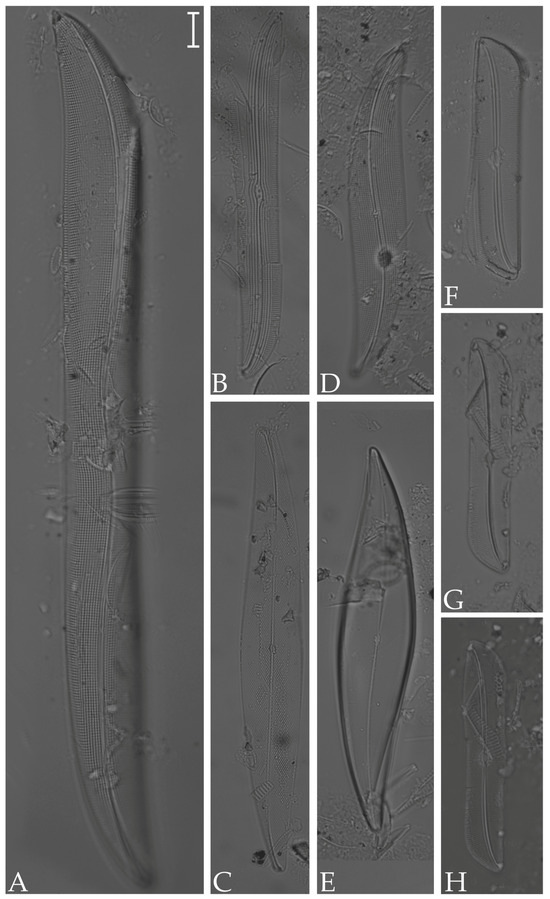

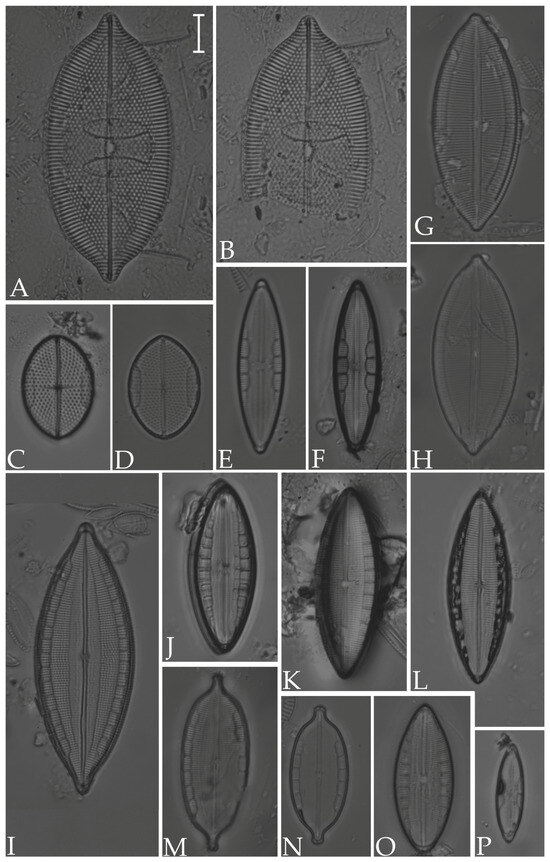

The inspection of the brushed-off material from the green crab’s carapaces yielded 106 diatom taxa belonging to 46 genera (Table 1; Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18). At the class level, 91% (97 taxa) were Bacillariophyceae, 5% (5) were Coscinodiscophyceae, and 4% (4) were Mediophyceae. The taxonomic families with most species were Bacillariaceae (with 17), Mastogloiaceae (9), Naviculaceae (9), and Diploneidaceae (8). Meanwhile, the highest-represented genera in terms of the number of species were Nitzschia (10), Mastogloia (9), Diploneis (8), Navicula (7), Amphora (5), Cocconeis (5), Tryblionella (4), and Gyrosigma (4), which accounted for 49% of all taxa. We found that 25 genera were singletons, i.e., they included a single taxon, representing 23% of all the records (Table 1). The most frequent species were Navicula normaloides (Figure 13E) and N. platyventris (Figure 13H–K). Meanwhile, Biddulphia californica (Figure 3A,B), Campylodiscus subangularis (Figure 18L,O), Melosira westii var. quadrata (Figure 3H,I), Nitzschia ligowskii (Figure 17M,N), Petroneis besarensis (Figure 9D–F), and Tryblionella pararostrata (Figure 16N) are new records for the study area and the northwestern Mexican region. This means that 93% of the diatom taxa that we found on the carapace of the green crabs were also characteristic or typical of the local epipelic diatom flora recorded for mangrove sediments in the region. This constitutes evidence that refutes the proposed null hypothesis, thus supporting an alternate hypothesis.

Table 1.

Systematic list of epibiotic diatom taxa found on carapaces of green swimming crabs (Callinectes bellicosus) from La Paz lagoon, Mexico. * = new record for the Mexican northwestern; SG = singleton (genus).

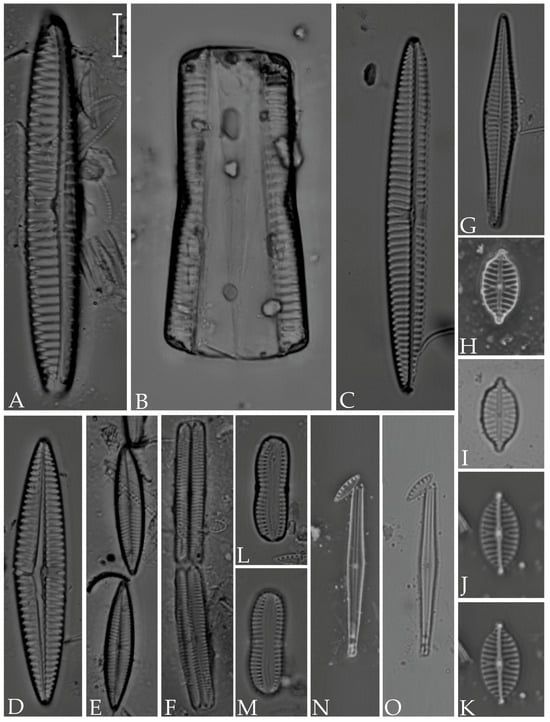

Figure 3.

(A,B) Biddulphia californica; (C) Ralfsiella smithii; (D) Odontella aurita; (E,F) Actinoptychus senarius; (G) Melosira distans var. lyrata; (H,I) M. westii var. quadrata; (J) M. nummuloides; (K,L) Paralia sulcata. Scale bar = 10 µm.

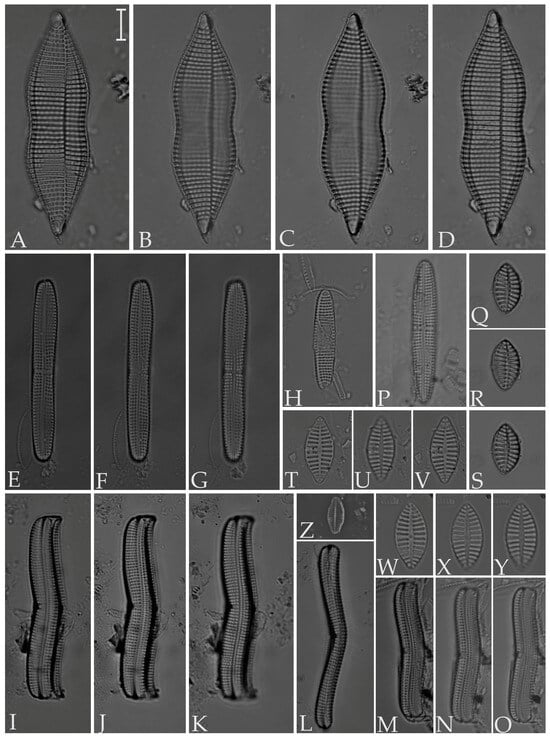

Figure 4.

(A–E) Plagiogramma minus; (F–I) P. tenuistriatum; (J,K) Dimeregramma maculatum; (L) Opephora mutabilis; (M) O. pacifica; (N) Staurosirella martyi; (O) Delphineis minutissima; (P) Grammatophora oceanica; (Q–S) Tabularia fasciculata; (T) T. tabulata; (U,V) Eunotogramma laeve; (W,X) Rhaphoneis castracanei; (Y,Z) Nitzschia fusoides. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Figure 5.

(A–D) Achnanthes yaquinensis; (E–P) A. brevipes var. angustata; (Q–S) Planothidium delicatulum var.?; (T–Y) P. hauckianum. (Z) Karayevia cf. amoena. Scale bar = 10 µm.

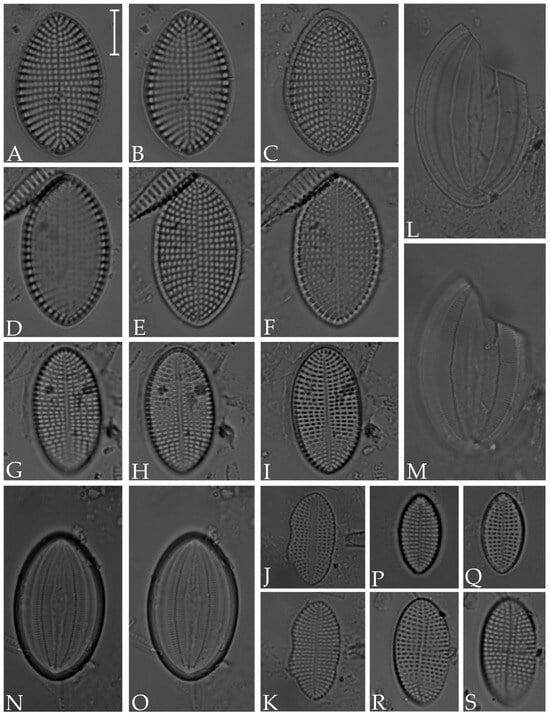

Figure 6.

(A–F) Cocconeis scutellum; (G–K) C. cf. euglypta; (L–O) C. pseudomarginata; (P,Q) C. cf. pseudolineata; (R,S) C. pseudodiruptoides. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Figure 7.

(A–C) Caloneis linearis; (D–G) Seminavis robusta; (H) Parlibellus rhombicula. Scale bar = 10 µm.

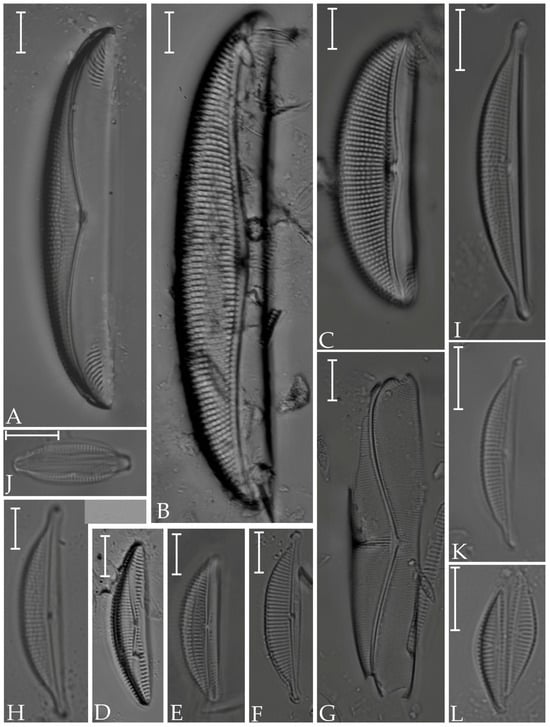

Figure 8.

(A,F) Diploneis gruendleri; (B–E) D. gravelleana; (G,H) D. obliqua; (I) D. coffeiformis; (J) D. interrupta; (K) D. vacillans; (L–P) D. smithii. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Figure 9.

(A) Lyrella exsul; (B,C) Petroneis granulata; (D–F) P. besarensis. Scale bar = 10 µm.

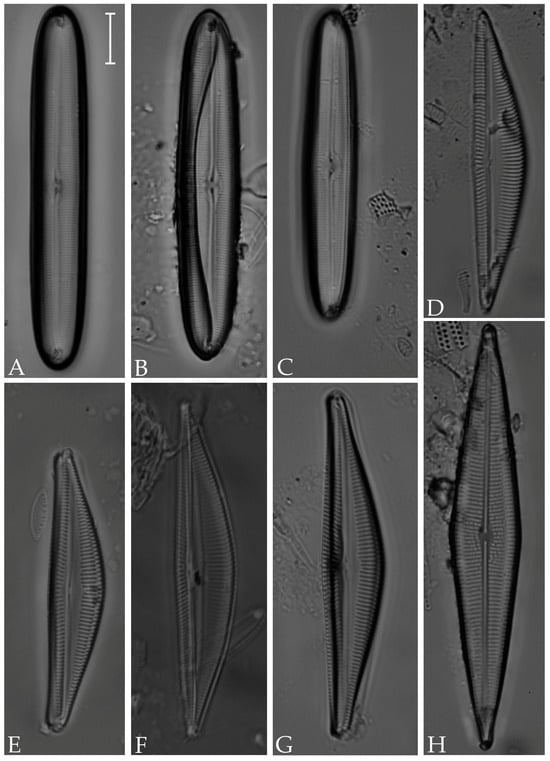

Figure 10.

(A–E) Fallacia nummularia; (F,G) F. litoricola. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Figure 11.

(A) Gyrosigma balticum; (B) G. variistriatum; (C) Pleurosigma salinarum; (D) Gyrosigma peisonis; (E) Pleurosigma diversestriatum; (F–H) Gyrosigma eximium. Scale bar = 10 µm.

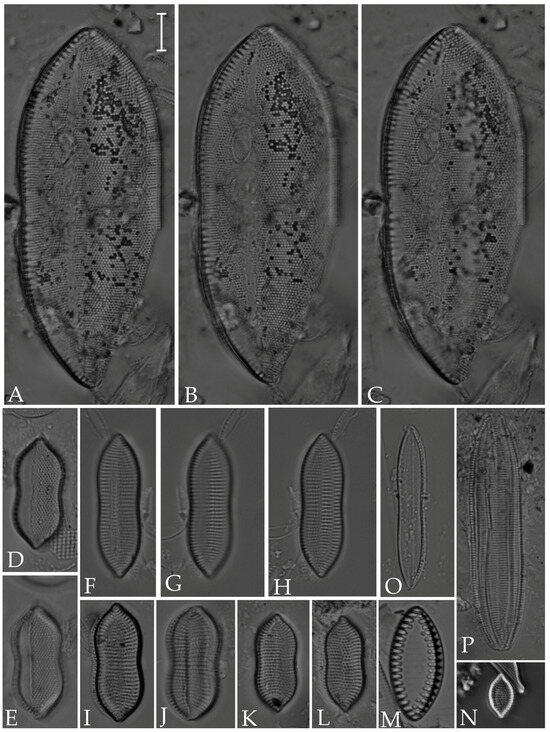

Figure 12.

(A,B) Mastogloia angulata; (C,D) M. binotata; (E,F) M. exigua; (G,H) M. apiculata; (I) M. pisciculus; (J,O) M. braunii; (K,L) M. robusta; (M,N) M. acutiuscula var. elliptica; (P) M. gieskesii. Scale bar = 10 µm.

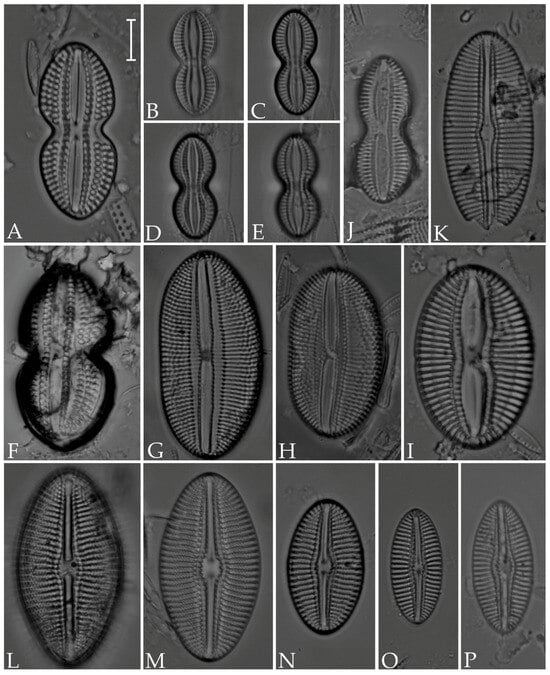

Figure 13.

(A,B) Navicula cancellata; (C) N. longa var. irregularis; (D) N. pennata; (E) N. normaloides; (F) N. cincta; (G) N. abunda; (H–K) N. platyventris; (L,M) Biremis ridicula (N,O) Brachysira cf. estoniarum. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Figure 14.

(A,B). Amphora proteus var. proteus; (C) A. proteus var. contigua; (D,E) A. marina; (F) A. holsaticoides; (G) A. cingulata; (H) Halamphora holsatica; (I,J) H. coffeiformis; (K) H. acutiuscula; (L) Navicymbula pusilla var. lata. Scale bars = 10 µm.

Figure 15.

(A) Plagiotropis pusilla; (B,C) Trachyneis velata; (D,E) T. aspera; (F,G) Entomoneis paludosa. Scale bars = 10 µm.

Figure 16.

(A–C) Psammodictyon panduriforme; (D,E) P. constrictum; (F–L) Tryblionella coarctata; (M) T. hyalina; (N) T. pararostrata; (O,P) T. hungarica. Scale bar = 10 µm.

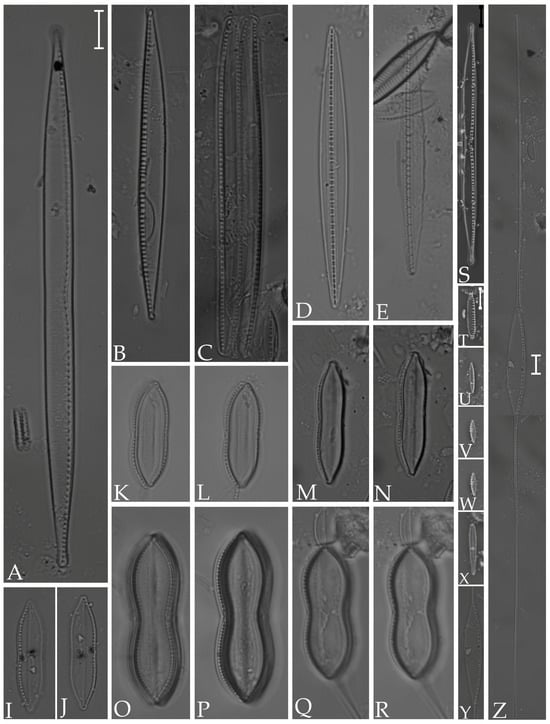

Figure 17.

(A) Nitzschia vidovichii; (B,C) N. sigma; (D,E) Homoeocladia distans; (I,J) Nitzschia subconstricta; (K,L) N. persuadens; (M,N) N. ligowskii; (O–R) N. carnicobarica; (S) N. scalpelliformis; (T–W) N. frustulum; (Y,Z) N. longissima; (X) Gomphoseptatum aestuarii. Scale bars = 10 µm.

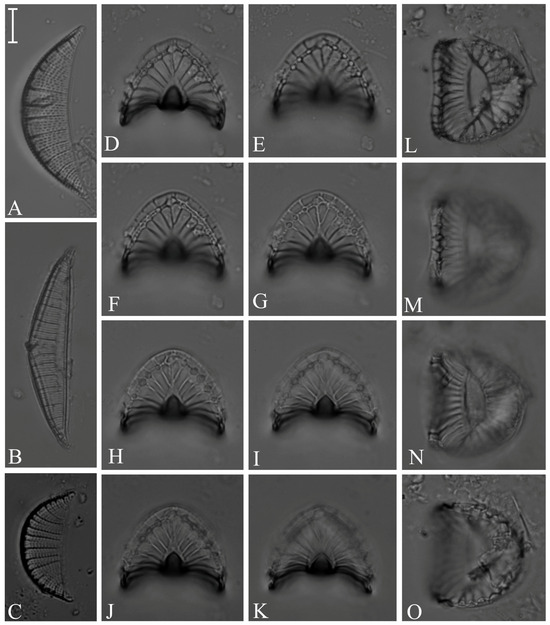

Figure 18.

(A) Rhopalodia gibberula; (B) R. acuminata; (C) R. musculus; (D–K) Coronia ambigua; (L–O) Campylodiscus subangularis. Scale bars = 10 µm.

4. Discussion

The study area consists mainly of mangrove swamps; thus, soft sediments dominate the bottom substrate, with a low availability of hard substrate. This means that hard-shell organisms (such as green swimming crabs) may serve as an alternate substrate for the colonization and settlement of multiple forms of benthic diatoms [17]. In fact, our species richness estimation bears the closest resemblance to the estimated values in previous studies of benthic diatom taxocoenoses from mangrove environments in the La Paz coastal lagoon [52,53,54]; the latter study yielded 150 taxa recorded overall on several pro-thrombolytic platforms, of which 42% were also found on the inspected green swimming crabs’ carapaces. That is, at 53 taxa per crab-specimen, the species richness falls within the interval estimated for samples of benthic diatom assemblages from mangrove (productive) environments [55].

Although studies on benthic diatoms in the northwest Mexican region are scarce and recent, several have been carried out expressly in the mangrove environments and have yielded a high species richness of diatoms thriving in the sediments [55]. Epipelic diatoms from these environments may constitute a reserve of potential colonizers for various basibionts, including the highly motile green crab, which may also represent a small-scale dispersion vehicle for benthic diatoms.

When comparing the species richness value estimated in our work (106 taxa) with those of similar studies with other crab species, we found that species richness estimations in said studies were reported to be lower. However, no comparison can be made between this diatom flora and those from other studies with the green swimming crab (or even other crabs from the same genus) because none have been conducted. The closest reference is a study by the authors of [18], which inspected basibiotic diatoms on a quite-different marine arthropod, albeit with what seems to be a similar adhesion surface, the horseshoe crab (Tachypleus gigas O. F. Müller 1785), a species that dwells in moderately deep waters and migrates nearshore for breeding. These authors recorded 17 and 20 diatom taxa living on female and male specimens, respectively, while considering studies with crabs in general, 65 diatom taxa were recorded as epibionts from 25 genera living on spider crabs (Schizophrys dahlak Griffin & Tranter 1986), confirming that the number of epizoic diatom taxa are normally much lower than in our study (less than half, in this case). However, life habits between these crab species are quite different, and the comparison may just be related to the composition of the carapace.

Beyond this, there is great potential before further studies to be added to the literature. For instance, eventhough the floristic reference for the northwestern Mexican region is considerable, the epibiotic taxocenosis on green swimming crabs rendered six new records. This does not necessarily mean that these are epizoic forms, but it supports the premise that continuous and extensive sampling—including various substrates and unexplored areas—along with exhaustive floristic inspection of the samples will enrich the benthic diatom species list, even at a global scale. This was earlier observed by the authors of [56], who recorded thirty diatom epizoic taxa on specimens of stone fish (Scorpaena mystes Jordan and Starks 1895), from the central Gulf of California, which were new for Mexican littorals, and out of which twelve had not hitherto been recorded for American coasts. As such, evidently, floristic records of benthic diatoms for the La Paz lagoon are far from complete. Furthermore, the records that are currently available are the products of discrete sampling, both spatially and temporally, as is the case for epibiotic taxa on green swimming crabs. They are also limited by sampling size; for instance, the authors of [56] inspected twenty specimens of stone fish, while for the present study, only two specimens of Callinectes bellicosus were used.

In this study, 93% of the diatom taxa found on the carapace of the green crabs are typical of the local epipelic diatom flora, a degree of similarity that refuted our null hypothesis, i.e., supporting the alternate hypothesis that the epibiotic diatom assemblages living on the carapaces of green crabs are composed mainly of typical or characteristic taxa found in mangrove sediments or from neighbor sites in northwestern Mexico. With respect to the significance of said similarity, in our own experience, even replicas or repetitions of samples may vary in similarity from 70 to 80% vs. the main sample when using similarity indices [57]. However, because differences in species richness affect the similarity value, the approach that we used was direct.

Further hypothesis-driven studies on the ecological relations and small-scale dispersion of benthic diatoms by means of green crab transportation will provide fertile grounds for improving our understanding of the interactive dynamics of epibionts and basibionts. In the case of Callinectes bellicosus and diatoms, this research should also help to complete our knowledge of those diatom taxa that are either epizoic or opportunistic, by working to overcome the evident spatial and temporal limitations of the existing contributions to floristic records for the Mexican coasts. In this manner, it may be explored if the species composition or the structure of the epibiotic assemblages aligns with the theoretical patchy distribution typical of benthic diatoms. Furthermore, considering the limited displacement capability of this basibiont, the inspection of specimens of green crab collected in other locations of the La Paz lagoon could broaden our knowledge by yielding distinct epibiotic diatom taxa.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.O.L.-F. and D.A.S.B.; internal funding acquisition, L.H. and S.F.-R.; investigation, F.O.L.-F., D.A.S.B., L.H. and S.F.-R.; resources, L.H. and S.F.-R.; writing—original draft, F.O.L.-F.; writing—review and editing, D.A.S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The green swimming crab specimens were collected by Claudia Yamilet Pinto Pimentel, Marcela Adriana Coronado Guillén, Camila Rebolledo Landero, Aleana Isabel Nazario Peña, Karin Victoria Burkart Jiménez, Catherine Naholi Montenegro Lagunas and Sebastián Aguirre. D.A.S.B. is a COFAA and EDI fellow of the IPN. F.O.L.F. Thanks are due for the support of the PRODEP and SNII-CONAHCYT programs. We sincerely acknowledge the efforts by two anonymous reviewers for the improvement of our manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dvoretsky, A.G.; Dvoretsky, V.G. Epibiotic communities of common crab species in the coastal Barents Sea: Biodiversity and infestation patterns. Diversity 2022, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totti, C.; Romagnoli, T.; De Stefano, M.; Camillo, D.C.G.; Bavestrello, G. The diversity of epizoic Diatoms. In All Flesh Is Grass. Cellular Origin, Life in Extreme Habitats and Astrobiology; Dubinsky, Z., Seckbach, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiffany, M.A. Epizoic and Epiphytic Diatoms. In The Diatom World; Seckbach, J., Kociolek, J.P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wujek, D.E. Epizoic Diatoms on the cerci of Ephemenoptera (Caenidae) Naiads. Great Lakes Entomol. 2013, 46, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribb, A.B. Algae on the Hawks-Bill turtle. Qsl. Nat. 1969, 19, 108–109. [Google Scholar]

- Croll, D.A.; Holmes, R.-W. A note on the occurrence of diatoms on the feathers of diving seabirds. Auk 1982, 99, 765–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denys, L. Morphology and taxonomy of epizoic diatoms (Epiphalaina and Tursiocola) on a sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) stranded on the coast of Belgium. Diatom. Res. 1997, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, T.J. On the diatoms of the skin film of whales, and their possible bearing on problems of whale movements. Discov. Rep. 1935, 10, 247–282. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, R.W. The Morphology of diatoms epizoic on Cetaceans and their transfer from Cocconeis to two new genera, Bennettella and Epipellis. Br. Phycol. J. 1985, 20, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K. Epibionts on carapaces of some Malacostracans from the Gulf of Thailand. J. Crustac. Biol. 1996, 16, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiser, E.E.; Bachmann, R.W. The ecology and taxonomy of epizoic diatoms on Cladocera. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1993, 38, 628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R.A. Pseudohimantidium pacificum, an epizoic diatom new to the Florida current (western North Atlantic Ocean). J. Phyc. 1978, 14, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.K.S.K.; Livingston, R.J.; Ray, G.L. The marine epizoic diatom Falcula hyaline from Chactawatchee Bay, the northeastern Gulf of Mexico: Frustule morphology and ecology. Diatom. Res. 1989, 4, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.J.; Norris, R.E. Ecology and taxonomy of an epizoic diatom. Pac. Sci. 1971, 25, 357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Key, M.M.; Winston, J.E.; Volpe, J.W.; Jeffries, W.B.; Voris, H.K. Briozoan fouling of the blue crab Callinectes sapidus at Beaufort, North Caroline. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1999, 64, 513–533. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Vargas, D.P.; Hendrickx, M.E. Utilization of algae and sponges by tropical decorating crabs (Majidae) in the Southeastern Gulf of California. Rev. Biol. Trop. 1987, 35, 161–164. [Google Scholar]

- Madkour, F.F.; Sallam, W.S.; Wicksten, M.K. Epibiota of the spider crab Schizophrys dahlak (Brachyura: Majidae) from the Suez Canal with special reference to epizoic diatoms. Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 2012, 5, e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, J.S.; Anil, A.C. Epibiotic community of the horseshoe crab Tachypleus gigas. Mar Biol. 2000, 136, 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Montes, R.; De la Cruz-Agüero, G.; Villalejo-Fuerte, M.T.; Duarte-Plata, G. Fecundidad de Callinectes arcuatus (Ordway, 1863) y C. bellicosus (Stimpson, 1859) (Decapoda: Brachyura: Portunidae) en la Ensenada de La Paz, Golfo de California, México. Univ. Cienc. 2013, 29, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx, M.E. Cangrejos. In Guía FAO para la Identificación de Especies para los Fines de la Pesca. Pacífico Centro-Oriental. Volumen, I. In Plantas e Invertebrados; Fischer, W., Krupp, F., Schneider, W., Sommer, C., Carpenter, K.E., Niem, V.H., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1995; Volume I, pp. 565–636. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, L.; Arreola-Lizárraga, J.A. Estructura de tallas y crecimiento de los cangrejos Callinectes arcuatus y C. bellicosus (Decapoda: Portunidae) en la laguna costera Las Guásimas, México. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2007, 55, 225–233. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=44955124 (accessed on 1 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Hines, A.H.; Lipcius, R.N.; Haddon, A.M. Population dynamics and habitat partitioning by size, sex and molt stage of blue crab Callinectes sapidus in a subestuary of central Chesapeake Bay. Mar. Ecol. 1987, 36, 55–64. Available online: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles/1982 (accessed on 1 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- McLay, C.L. Dispersal and use of sponges and ascidian camouflage by Cryptodromia hilgendorfi (Brachyura: Decapoda). Mar. Biol. 1983, 76, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Wada, K. Resource utilization for decorating in three intertidal Majidae crabs (Brachyura: Majidae). Mar. Biol. 2000, 137, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fuerte, F.O.; Siqueiros Beltrones, D.A. A checklist of marine benthic diatoms (Bacillariophyta) from Mexico. Phytotaxa 2016, 283, 201–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleve-Euler, A. Die Diatomeen von Schweden und Finnland. Part V. (Schluss.). K. Sven. Vetensk. Akad. Handl. Ser. 4 1952, 3, 1–153. [Google Scholar]

- Cleve-Euler, A. Die Diatomeen Von Schweden und Finnland. Teil II. Araphideae, Brachyraphideae. Mit 35 Tafeln; Almqvist & Wiksells Boktryckeri Ab: Stockholm, Sweden, 1953; p. 158. [Google Scholar]

- Cleve-Euler, A. Die Diatomeen von Schweden und Finnland. Part III. Monoraphideae, Biraphideae 1; Kongliga Svenska Vetenskaps Akademiens Handligar: Stockholm, Sweden, 1953; p. 255. [Google Scholar]

- Cleve-Euler, A. Die Diatomeen von Schweden und Finnland. Part IV. Biraphideae 2. K. Sven. Vetensk. Akad. Handl. Ser. 4 1955, 5, 1–232. [Google Scholar]

- Foged, N. Some littoral diatoms from the coasts of Tanzania. Biblioth. Phycol. 1975, 16, 1–127. [Google Scholar]

- Foged, N. Diatoms in Eastern Australia. Biblioth. Phycol. 1978, 41, 1–243. [Google Scholar]

- Foged, N. Freshwater and littoral diatoms from Cuba. Biblioth. Diatom. 1984, 5, 1–242. [Google Scholar]

- Hustedt, F. Die kieselalgen Deutschlands, Osterreichs and der Schweis, Bacillariophyta (Diatomae) Heft 10. In Die Süsswasser-Flora Mitteleuropas; Pascher, A., Ed.; Gustav Fischer: Jena, Germany, 1930; p. 466. [Google Scholar]

- Hustedt, F. Die kieselalgen Deutschlands, Osterreichs and der Schweis. In Kryptogammen-Flora; VII Band, II Teil; Rabenhorts, L., Ed.; Koeltz Scientific Book: Leipzig, Germany, 1959; p. 845. [Google Scholar]

- Hustedt, F. Die kieselalgen Deutschlands, Osterreichs and der Schweis. In Kryptogammen-Flora; VII Band, III Teil; Rabenhorst, L., Ed.; Koeltz Scientific Book: Leipzig, Germany, 1966; p. 816. [Google Scholar]

- Krammer, K.; Lange-Bertalot, H. Bacillariophyceae 3. Teil: Centrales, Fragilariaceae, Eunotiaceae. In Suesswasserflora von Mitteleuropa 2 (3); Gustav Fisher: Jena, Germany, 1991; 576p. [Google Scholar]

- Lange-Bertalot, H.; Krammer, K. Bacillariaceae, Epithemiaceae, Surirellaceae. Neue und wenig bekannte Taxa, neue Kombinationen und Synonyme sowie Bemerkungen und Ergänzungen zu den Naviculaceae. Biblioth. Diatom. 1987, 15, 1–289. [Google Scholar]

- Lange-Bertalot, H.; Kulbs, K.; Lauser, T.; Norpel-Schempp, M.; Willmann, M. Diatom taxa introduced by Georg Krasske: Documentation and revision. In Iconographia Diatomologica; Lange-Bertalot, H., Ed.; Koeltz Scientific Books: Konigstein, Germany, 1996; Volume 3, 358p. [Google Scholar]

- Lobban, C.S.; Schefter, M.; Jordan, R.W.; Arai, Y.U.; Sasaki, A.S.; Theriot, E.C.; Ashworth, M.A.; Ruck, E.C.; Pennesi, C.H. Coral-reef diatoms (Bacillariophyta) from Guam: New records and preliminary checklist, with emphasis on epiphytic species from farmer-fish territories. Micronesica 2012, 43, 237–479. [Google Scholar]

- Loir, M.; Novarino, G. Marine Mastogloia Thwaites ex W. Sm. and Stigmaphora Wallich Species from the French Lesser Antille; Diatom Monographs, Koeltz Scientific Books: Königstein, Germany, 2013; Volume 16, p. 133. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J.L.; Licea, S.; Santoyo, H. Diatomeas del Golfo de California; Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur-SEP-FOMESPROMARCO: Tijuana, Mexico, 1996; p. 273. [Google Scholar]

- Peragallo, H.; Peragallo, M. Diatomées Marines de France et des Districts Maritimes Voisins; Tempère, J., Ed.; Micrographe-Editeur: À Grez-sur-Loing, France, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A.; Schmidt, M.V.; Fricke, F.V.; Heiden, H.; Muller, O.; Hustedt, F. Atlas der Diatomaceenkunde; Heft 1–120, Tafeln 1–460; Reisland: Leipzig, Germany, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Stidolph, S.R.; Sterrenburg, F.A.S.; Smith, K.E.L.; Kraberg, A.; Stuart, R. Stidolph Diatom Atlas. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2012-1163. Available online: http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1163/ (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Witkowski, A.; Lange-Bertalot, H.; Metzeltin, D. Diatom Flora of Marine Coasts. In Iconographia Diatomologica; Lange-Bertalot, H., Ed.; Koeltz Scientific Books: Königstein, Germany, 2000; pp. 1–925. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, J.C. Araphid and monoraphid diatoms. In Freshwater Algae of North America, Ecology and Classification; Wehr, J.D., Sheath, R.G., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 595–636. [Google Scholar]

- Kociolek, J.P.; Spaulding, S.A. Symmetrical naviculoid diatoms. In Freshwater Algae of North America, Ecology and Classification; Wehr, J.D., Sheath, R.G., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 637–654. [Google Scholar]

- Medlin, L.K.; Kaczmarska, I. Evolution of the diatoms: V. Morphological and cytological support for the major clades and a taxonomic revision. Phycologia 2004, 43, 245–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Round, F.E.; Crawford, R.M.; Mann, D.G. The Diatoms: Biology & Morphology of the Genera; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; p. 747. [Google Scholar]

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. Algaebase. World-Wide Electronic Publication; National University of Ireland: Galway, Ireland; Available online: http://www.algaebase.org (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- WoRMS Editorial Board. World Register ofMarine Species. Available online: http://www.marinespecies.org (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Siqueiros Beltrones, D.A. Diatomeas bentónicas asociadas a trombolitos vivos registrados por primera vez en México. CICIMAR Oceán. 2006, 21, 113–143. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueiros Beltrones, D.A.; Morzaria Luna, H. New records of marine benthic diatom species for the north-western Mexican region. Oceánides 1999, 14, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueiros Beltrones, D.A.; Sánchez-Castrejón, E. Structure of benthic diatom assemblages from a mangrove environment in a Mexican Subtropical Lagoon. Biotropica 1999, 31, 48–70. [Google Scholar]

- López-Fuerte, F.O.; Siqueiros Beltrones, D.A.; Navarro, J.N. Benthic Diatoms Associated with Mangrove Environments in the Northwest Region of Mexico; CONABIO-UABCS-IPN: La Paz, Mexico, 2010; p. 217. [Google Scholar]

- López-Fuerte, F.; Siqueiros-Beltrones, D.; Jakes-Cota, U.; Tripp-Valdéz, A. New Records of Marine Diatoms for the American Continent Found on Stone Scorpionfish Scorpaena mystes. Open J. Mar. Sci. 2019, 9, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueiros Beltrones, D.A.; López-Fuerte, F.O.; Martínez, Y.J.; Altamirano-Cerecedo, M.C. A first estimate of species diversity for benthic diatom assemblages from the Revillagigedo Archipelago, Mexico. Diversity 2021, 13, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).