Diversity and Biosynthetic Activities of Agarwood Associated Fungi

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Agarwood-Producing Trees and Their Geographical Distribution

1.2. Fragrant Purposes and Medicinal Uses of Agarwood

1.3. Three Methods That Induce the Production of Agarwood

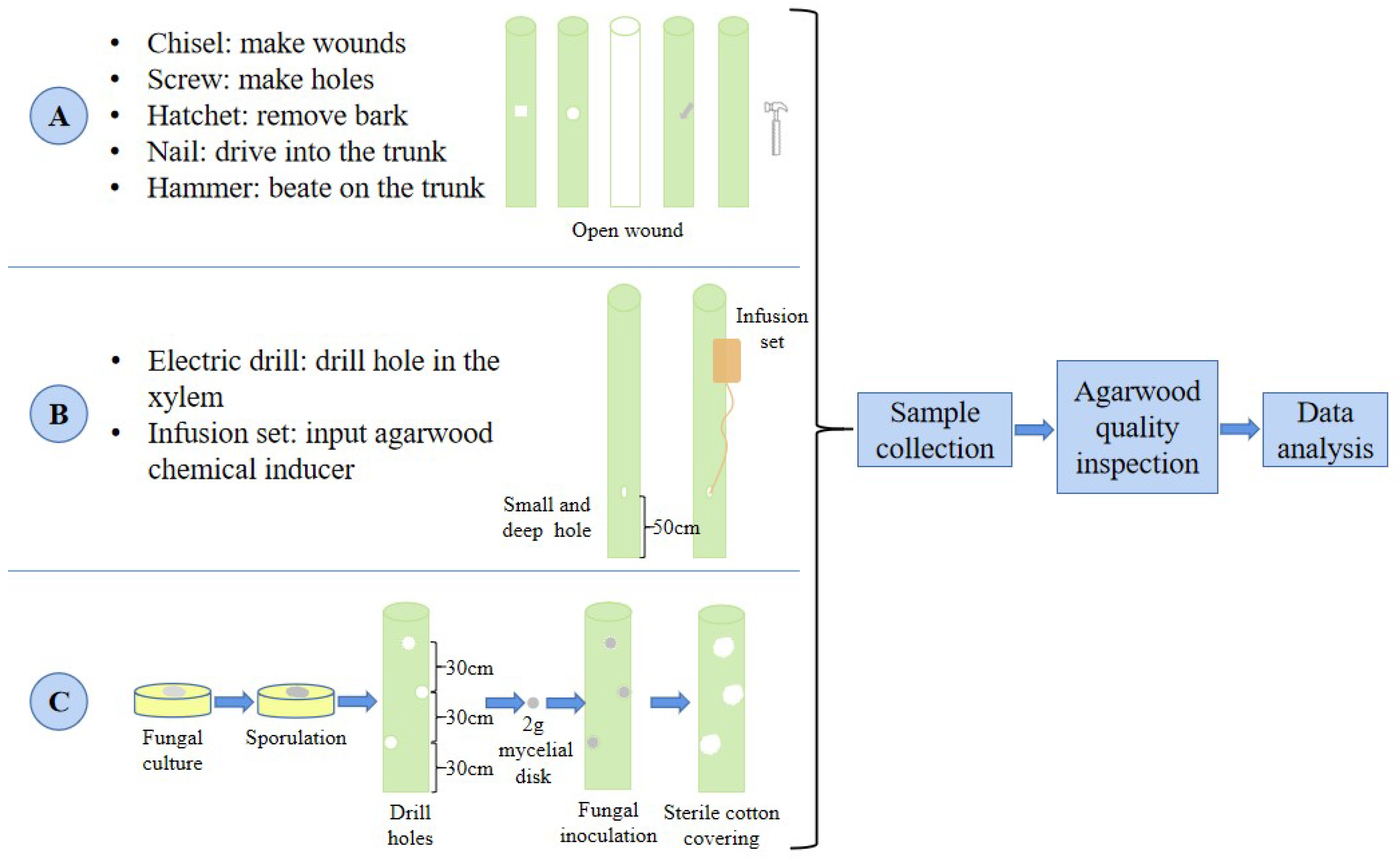

1.3.1. Physical Injury

1.3.2. Chemical Inducer

1.3.3. Biological Inoculation (Fungal Inoculation)

| Endophytic Fungi | Agarwood-Producing Tree Species | Isolation Source | The Ability to Induce Agarwood | Bioactivity/Important Metabolites | Country | References |

| Aspergillus sp. | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | Y | N/A | India | [58] |

| Botryodyplodis | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | Y | N/A | India | [58] |

| Botryosphaeria dothidea | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | Y | N/A | India | [58] |

| Diplodia sp. | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | Y | N/A | India | [58] |

| Several fungi isolated from Aquilaria agallocha | Aquilaria agallocha | N/A | N | N/A | N/A | [59] |

| Epicoccum granulatum | Aquilaria agallocha | N/A | Y | N/A | India | [60] |

| Cladosporium sp. | Aquilaria agallocha | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [61] |

| Torula sp. | Aquilaria agallocha | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [61] |

| Phialophora parasitica | Aquilaria agallocha | N/A | N | N/A | N/A | [62] |

| Aspergillus sp. | Aquilaria agallocha | infected wood | N | N/A | N/A | [37] |

| Aspergillus tamarii | Aquilaria agallocha | infected wood | N | N/A | N/A | [37] |

| Botryodiplodia theobromae | Aquilaria agallocha | infected wood | N | N/A | N/A | [37] |

| Fusarium solani | Aquilaria agallocha | infected wood | N | N/A | N/A | [37] |

| Penicillium citrinum | Aquilaria agallocha | infected wood | N | N/A | N/A | [37] |

| Fusarium bulbigenium | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [63] |

| Fusarium lateritium | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [63] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [63] |

| Melanotus flavolivens | Aquilaria sinensis | N/A | Y | N/A | China | [30] |

| Chaetomium globosum | Aquilaria agallocha | N/A | Y | N/A | India | [47] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Aquilaria agallocha | N/A | Y | N/A | India | [47] |

| Fusarium sp. | Aquilaria sp. | Agarwood samples | Y | N/A | Indonesia | [48] |

| Fusarium sp. | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | Y | N/A | Sumatra island | [48] |

| Fusarium sp. | Gyrinops versteegii | Agarwood samples | Y | N/A | Indonesia | [48] |

| Chaetomium globosum | Aquilaria agallocha | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [49] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Aquilaria agallocha | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [49] |

| Acremonium sp. | Aquilaria microcarpa | N/A | Y | N/A | Malaysia | [50] |

| Botryosphaeria rhodina | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Cephalosporium sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Cladophialophora sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Cladosporium edgeworthrae | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Colletotrichum sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Epicoccum sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Fusarium sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Geotrichum sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Glomerularia sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Gonytrichum sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Guignardia manqiferae | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Monilia sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Mortierella sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Mycelia sterilia sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Ovulariopsis sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Penicillium sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Pleospora sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Rhinocladiella sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | Antimicrobial activity | China | [64] |

| Fusarium moniliforme | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [51] |

| Fusarium sambucinum | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [51] |

| Fusarium solani | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [51] |

| Fusarium tricinctum | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [51] |

| Melanotus flavolivens | Aquilaria sinensis | N/A | Y | Sesquiterpenes, aromatic constituents, and fatty acids | China | [65] |

| Fusarium solani | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood chips | N | N/A | Malaysia | [66] |

| Fusarium sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood chips | N | N/A | Malaysia | [66] |

| Hypocrea lixii | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood chips | N | N/A | Malaysia | [66] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood chips | N | N/A | Malaysia | [66] |

| Cochliobolus lunatus | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood chips | N | N/A | Malaysia | [66] |

| Cunninghamella bainieri | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood chips | N | N/A | Malaysia | [66] |

| Curvularia sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood chips | N | N/A | Malaysia | [66] |

| Trichoderma sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood chips | N | N/A | Malaysia | [66] |

| Nodulisporium sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem | N | Isofuranonaphthalenone, and benzopyran | China | [67] |

| Cladosporium tenuissimum | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [68] |

| Coniothyrium nitidae | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [68] |

| Epicoccum nigrum | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [68] |

| Fusarium equiseti | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [68] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [68] |

| Fusarium solani | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [68] |

| Hypocrea lixii | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [68] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [68] |

| Leptosphaerulina chartarum | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [68] |

| Paraconiothyrium variabile | Aquilaria sinensi | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [68] |

| Phaeoacremonium rubrigenum | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [68] |

| Phoma herbarum | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [68] |

| Rhizomucor variabilis | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [68] |

| Fusarium sp. | Aquilaria microcarpa | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [52] |

| Fimetariella rabenhorstii | Aquilaria sinensis | N/A | N | Frabenol (Sesquiterpene alcohol) | China | [69] |

| Fusarium sp. | Aquilaria beccariana | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [53] |

| Trichoderma spirale | Aquilaria sinensis | N/A | N | Trichodermic acid A, trichodermic acid B, known trichodermic acid and trichodermamide A | China | [70] |

| Lasiodiplodia sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Natural agarwood | Y | N/A | China | [45] |

| Xylaria sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Natural agarwood | Y | N/A | China | [45] |

| Paraconiothyrium variabile | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | Y | N/A | China | [71] |

| Alternaria sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood samples | N | N/A | India | [72] |

| Cladosporium cladosporoides | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood samples | N | N/A | India | [72] |

| Cladosporium sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood samples | N | N/A | India | [72] |

| Curvularia sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood samples | N | N/A | India | [72] |

| Davidiella tassiana | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood samples | N | N/A | India | [72] |

| Fusarium solani | Aquilaria malaccensis | Agarwood samples | N | N/A | India | [72] |

| Hypocrea fairnosa | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood samples | N | N/A | India | [72] |

| Massarina albocarnis | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood samples | N | N/A | India | [72] |

| Phaeoacremonium | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood samples | N | N/A | India | [72] |

| Pichia sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood samples | N | N/A | India | [72] |

| Trichoderma sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Wood samples | N | N/A | India | [72] |

| Alternaria sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (nonresinous trees) | Leaves | N | N/A | China | [32] |

| Botryosphaeria sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (agarwood-producing wounded tree) | Leaves | Y | Sesquiterpenes, 2-(2-phenylethyl) chromanone, aromatics, fatty acids and esters | China | [32] |

| Chaetomium sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (agarwood-producing wounded tree) | N/A | N | N/A | China | [32] |

| Colletotrichum gleosporiodes | Aquilaria sinensis (agarwood-producing wounded tree) | Leaves | N | N/A | China | [32] |

| Cylindrocladium sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (agarwood-producing wounded tree) | Leaves | N | N/A | China | [32] |

| Fusarium sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (agarwood-producing wounded tree) | N/A | Y | Sesquiterpenes, 2-(2-phenylethyl) chromanone, aromatics, fatty acids and esters | China | [32] |

| Mycosphaerella sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (nonresinous trees) | Leaves | N | Sesquiterpenes, 2-(2-phenylethyl) chromanone, aromatics, fatty acids and esters | China | [32] |

| Nodulisporium sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (agarwood-producing wounded tree) | N/A | N | N/A | China | [32] |

| Penicillium sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (agarwood-producing wounded tree) | N/A | N | N/A | China | [32] |

| Pestalotiopsis sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (agarwood-producing wounded tree) | N/A | N | N/A | China | [32] |

| Phoma sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (nonresinous trees) | Leaves | N | N/A | China | [32] |

| Phomopsis sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (agarwood-producing wounded tree) | Leaves | N | N/A | China | [32] |

| Ramichloridium sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (nonresinous trees) | Leaves | N | N/A | China | [32] |

| Sagenomella sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (nonresinous trees) | Leaves | N | N/A | China | [32] |

| Xylaria mali | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | China | [32] |

| Xylaria sp. | Aquilaria sinensis (agarwood-producing wounded tree) | N/A | N | N/A | China | [32] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Aquilaria sinensis | Diseased branch | Y | Jasmonates, JAs | China | [29] |

| Nigrospora oryzae | Aquilaria sinensis | Stem, root and leaves | N | 11-Hydroxycapitulatin B and Capitulatin B | China | [73] |

| Unidentified five fungi belonging to the Deuteromycetes and Ascomycetes | Aquilaria malaccensis | N/A | Y | Benzylacetone, anisylacetone, guaiene and palustrol | Malaysia | [54] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | Y | Sesquiterpenes (agarospirol), aromatics compounds and alkanes | China | [74] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | Y | Sesquiterpenes (agarospirol), aromatics compounds and alkanes | China | [74] |

| Acremonium sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Agarwood samples pre-inoculated with Fusarium | N | N/A | N/A | [55] |

| Alternaria sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Agarwood samples pre-inoculated with Fusarium | N | N/A | N/A | [55] |

| Cladosporium sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Agarwood samples pre-inoculated with Fusarium | N | N/A | N/A | [55] |

| Fusarium sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Agarwood samples pre-inoculated with Fusarium | Y | N/A | N/A | [55] |

| Mucor sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Agarwood samples pre-inoculated with Fusarium | N | N/A | N/A | [55] |

| Nigrospora sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Agarwood samples pre-inoculated with Fusarium | N | N/A | N/A | [55] |

| Scopulariopsis sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Agarwood samples pre-inoculated with Fusarium | N | N/A | N/A | [55] |

| Scytalidium sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Agarwood samples pre-inoculated with Fusarium | N | N/A | N/A | [55] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Aquilaria sp. | Agarwood samples | N | N/A | Indonesia | [75] |

| Fusarium solani | Aquilaria sp. | Agarwood samples | N | N/A | Indonesia | [75] |

| Fusarium sp. | Aquilaria sp. | Agarwood samples | N | N/A | Indonesia | [75] |

| Fusarium verticillioides | Aquilaria crassna | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial activity | Vietnam | [76] |

| Geotrichum candium | Aquilaria crassna | Agarwood samples | N | Antimicrobial activity | Vietnam | [76] |

| Acremonium sp. | Aquilaria crassna | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [56] |

| Fusarium sp. | Aquilaria crassna | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | [56] |

| Fusarium solani | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | Y | N/A | China | [24] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | Y | N/A | China | [24] |

| Fusarium solani | Aquilaria malaccensis | From wild Aquilaria malaccensis | Y | Tridecanoic acid, a-santalol, and spathulenol | Indonesia | [44] |

| Fusarium sp. | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | Y | N/A | China | [77] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Aquilaria sinensis | Y | N/A | China | [77] | |

| Arthrinium sp. | Aquilaria subintegra | Fresh heartwood stems | N | β-agarofuran, α-agarofuran, δ-eudesmol, oxo-agarospirol, and β-dihydro agarofuran | Thailand | [31] |

| Colletotrichum sp. | Aquilaria subintegra | Fresh heartwood stems | N | β-agarofuran, α-agarofuran, δ-eudesmol, oxo-agarospirol, and β-dihydro agarofuran | Thailand | [31] |

| Diaporthe sp. | Aquilaria subintegra | Fresh heartwood stems | N | Excellent antioxidant capacity | Thailand | [31] |

| Fusarium sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Agarwood samples | Y | N/A | India | [78] |

| Rigidoporus vinctus | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | Y | N/A | China | [46] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Aquilaria sinensis | N/A | Y | N/A | China | [79] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Aquilaria sinensis | N/A | Y | N/A | China | [79] |

| Nigrospora oryzae | Aquilaria sinensis | N/A | Y | β-phenylethyl alcohol | China | [80] |

| Fusarium solani | Gyrinops versteegii | N/A | Y | Sesquiterpen, chromones, aromatic, fatty acid, triterpen | Indonesia | [81] |

| Fusarium solani | Aquilaria malaccensis | N/A | Y | Sesquiterpen, chromones, aromatic, fatty acid, triterpen | Indonesia | [81] |

| Aspergillus niger | Gyrinops walla | Agarwood samples | Y | Jinkohol, agarospirol and 2(2-phenyl) chromone derivatives, b-Seline, γ-eudesmol and valerenal, γ-Elemene | Sri Lanka | [28] |

| Fusarium solani | Gyrinops walla | Agarwood samples | Y | Jinkohol, agarospirol and 2(2-phenyl) chromone derivatives, b-Seline, γ-eudesmol and valerenal, γ-Elemene | Sri Lanka | [28] |

| Lasiodiplodia aquilariae | Aquilaria crassna | Agarwood samples | N | N/A | Laos | [3] |

| Lasiodiplodia brasiliensis | Aquilaria crassna | Agarwood samples | N | N/A | Laos | [3] |

| Lasiodiplodia curvata | Aquilaria crassna | Agarwood samples | N | N/A | Laos | [3] |

| Lasiodiplodia irregularis | Aquilaria crassna | Healthy tissue | N | N/A | Laos | [3] |

| Lasiodiplodia laosensis | Aquilaria crassna | Healthy tissue | N | N/A | Laos | [3] |

| Lasiodiplodia lignicola | Aquilaria crassna | Agarwood samples | N | N/A | Laos | [3] |

| Lasiodiplodia macroconidica | Aquilaria crassna | Agarwood samples | N | N/A | Laos | [3] |

| Lasiodiplodia microcondia | Aquilaria crassna | Healthy tissue | N | N/A | Laos | [3] |

| Lasiodiplodia pseudotheobromae | Aquilaria crassna | Healthy tissue and Agarwood samples | N | N/A | Laos | [3] |

| Lasiodiplodia sp. | Aquilaria crassna | Healthy tissue and Agarwood samples | N | N/A | Laos | [3] |

| Lasiodiplodia tenuiconidia | Aquilaria crassna | Agarwood samples | N | N/A | Laos | [3] |

| Lasiodiplodia tropica | Aquilaria crassna | Healthy tissue | N | N/A | Laos | [3] |

| Fusarium solani | Aquilaria sinensis | N/A | Y | N/A | China | [82] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Aquilaria sinensis | N/A | Y | N/A | China | [82] |

| Fusarium solani | Gyrinops versteegii | N/A | Y | (1) alloaromadendrene. (2) β-eudesmol. (3) β-selinene. (4) chromone derivatives 2-(2-phenylethyl) chromen-4-one. (5) 6-methoxy-2-(2-phenylethyl) chromen-4-one. (6) 6,7-dimethoxy-2-(2-phenylethyl) chromen-4-one. | Indonesia | [26] |

| Alternaria sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Juvenile (1-year-old) woods | N | N/A | India | [83] |

| Cladosporium sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Agarwood samples | N | Antibacterial effect against Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis | India | [83] |

| Curvularia sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Juvenile (1-year-old) woods | N | N/A | India | [83] |

| Fusarium sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Agarwood samples | N | N/A | India | [83] |

| Penicillium sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Agarwood samples | N | N/A | India | [83] |

| Rhizopus sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Juvenile (1-year-old) woods | N | N/A | India | [83] |

| Sterilia sp. | Aquilaria malaccensis | Juvenile (1-year-old) woods | N | N/A | India | [83] |

| Nemania aquilariae | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | (1) Bicyclo[3.1.1]hept-3-ene-2-acetaldehyde, 4,6,6-trime-thyl-, (1R,2R,5S) rel-. (2) Naphthalene,1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,7-octahydro-4a,8-dimethyl-2-(1-meth-ylethenyl)-. (3) Alloaromadendrene. (4) Valencen. (5) α-Selinene. (Antibacterial and antimicrobial) | China | [25] |

| Nemania yunnanensis | Aquilaria sinensis | Agarwood samples | N | N/A | China | [25] |

2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.Y.; Wei, J.H.; Gao, Z.H.; Zhang, Z.; Lyu, J.C. A review of quality assessment and grading for agarwood. Chin. Herb. Med. 2017, 9, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, Z.X.; Wang, C.H.; Wu, C.M.; Guo, P.; Wei, J.H. Chemical constituents and pharmacological activity of agarwood and Aquilaria plants. Molecules 2018, 23, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, S.; Zhao, L.; Sun, X.; He, W.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Y.C. Lasiodiplodia spp. associated with Aquilaria crassna in Laos. Mycol. Prog. 2019, 18, 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.S.; Isa, N.M.; Ismail, I.; Zainal, Z. Agarwood induction: Current developments and future perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.Q.; Wei, J.H.; Yang, J.S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Z.H.; Sui, C.; Gong, B. Chemical constituents of agarwood originating from the endemic genus Aquilaria plants. Chem. Biodivers. 2012, 9, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.; Mohamed, R. Understanding agarwood formation and its challenges. In Agarwood; Mohamed, R., Ed.; Tropical Forestry: Berlin, Germany; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 39–56, Chapter 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhipa, H.; Chowdhary, K.; Kaushik, N. Artificial production of agarwood oil in Aquilaria sp. by fungi: A review. Phytochem. Rev. 2017, 16, 835–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.H.; Liao, Y.C.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Sun, P.W.; Gao, Z.H.; Sui, C.; Wei, J.H. Jasmonic acid is a crucial signal transducer in heat shock induced sesquiterpene formation in Aquilaria sinensis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azren, P.D.; Lee, S.Y.; Emang, D.; Mohamed, R. History and perspectives of induction technology for agarwood production from cultivated Aquilaria in Asia: A review. J. For. Res. 2018, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persoon, G.A. Agarwood: The Life of a Wounded Tree; IIAS: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.L.; Liu, Y.Y.; Wei, J.H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.Q.; Chen, H.Q.; Liu, Y.J. Production of high-quality agarwood in Aquilaria sinensistrees via whole-tree agarwood-induction technology. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2012, 23, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Chen, H.Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, J.; Meng, H.; Chen, W.P.; Feng, J.D.; Gan, B.C.; Chen, X.Y.; et al. Whole-tree agarwood-inducing technique: An efficient novel technique for producing high-quality agarwood in cultivated Aquilaria sinensis trees. Molecules 2013, 18, 3086–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Pharmacopoeia Committee. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China; 2015 Version; Chinese Medical Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 185–186. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hindi, R.R.; Aly, S.E.; Hathout, A.S.; Alharbi, M.G.; Al-Masaudi, S.; Al-Jaouni, S.K.; Harakeh, S.M. Isolation and molecular characterization of mycotoxigenic fungi in agarwood. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 1781–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, R.; Kaushik, N. A review of chemistry, quality and analysis of infected agarwood tree (Aquilaria sp.). Phytochem. Rev. 2017, 16, 1045–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Islam, M.T.; Zulkefeli, M.; Khan, S.I. Agarwood production—A multidisciplinary field to be explored in Bangladesh. Int. Pharm. Life Sci. 2013, 2, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, K.; Kumar, A.; Menon, V. Trade in Agarwood; Traffic: New Delhi, India, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Barden, A.; Anak, N.A.; Mulliken, T.; Song, M. Heart of the Matter: Agarwood Use and Trade and CITES Implementation for Aquilaria Malaccensis; Traffic International: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, J.; Ishihara, A. The Use and Trade of Agarwood in Japan; Southeast Asia and East Asia-Japan, Traffic: 2006. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.459.1016&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- López-Sampson, A.; Page, T. History of use and trade of agarwood. Econ. Bot. 2018, 72, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turjaman, M.; Hidayat, A.; Santoso, E. Development of agarwood induction technology using endophytic fungi. In Agarwood; Mohamed, R., Ed.; Tropical Forestry; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Singapore, 2016; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CITES Secretariat Convention on international trade in endangered species of Wild Fauna and Flora. CoP13 Prop. 49. Consideration of proposals for amendment of Appendices I and II-Aquilaria spp. and Gyrinops spp. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties, Bangkok, Thailand, 2–14 October 2004; International Environment House: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. Appendices I, II, and III of CITES, UNEP; CITES: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; Liu, P.W.; Peng, D.Q.; Wei, J.H. Study on biological characteristics of two strains of Lasiodiplodia theobromae promoting agarwood formation. Acta Agric. Jiangxi 2017, 29, 95–98. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tibpromma, S.; Zhang, L.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Du, T.Y.; Wang, Y.H. Volatile constituents of endophytic fungi isolated from Aquilaria sinensis with descriptions of two new species of Nemania. Life 2021, 11, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faizal, A.; Azar, A.W.P.; Turjaman, M.; Esyanti, R.R. Fusarium solani induces the formation of agarwood in Gyrinops versteegii (Gilg.) Domke branches. Symbiosis 2020, 81, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurence, W.V.A. Isolation and Characterization of Endophytes Isolated from Akar Gaharu. Bachelor’s Research Dissertation, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Sarawak, Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Subasinghe, S.M.C.U.P.; Hitihamu, H.I.D.; KMEP, F. Use of two fungal species to induce agarwood resin formation in Gyrinops walla. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.M.; Liang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.J.; Yang, Y.; Meng, H.; Gao, Z.H.; Xu, Y.H. Sesquiterpenes induced by Chaetoceros cocoa on white wood incense. Chin. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2014, 39, 192. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qi, S.Y.; Lin, L.D.; Ye, Q.F. Benzylacetone in agarwood and its biotransformation by Melanotus flavolivens. Chin. J. Biotechnol. 1998, 14, 464–467. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Monggoot, S.; Popluechai, S.; Gentekaki, E.; Pripdeevech, P. Fungal endophytes: An alternative source for production of Volatile compounds from agarwood oil of Aquilaria subintegra. Microb. Ecol. 2017, 74, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.J.; Gao, X.X.; Zhang, W.M.; Wang, L.; Qu, L.H. Molecular identification of endophytic fungi from Aquilaria sinensis and artificial agarwood induced by pinholes-infusion technique. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 12, 3115–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Mohamed, R. The origin and domestication of Aquilaria, an important agarwood-producing genus. In Agarwood; Mohamed, R., Ed.; Tropical Forestry: Berlin, Germany; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 1–20, Chapter 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, H.Y.; Kerr, P.G.; Abbas, P.; Salleh, H.M. Aquilaria spp. (agarwood) as source of health beneficial compounds: A review of traditional use, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 189, 331–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anon. The Ayurvedic Formulary of India; The Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Department of Indian Systems of Medicine Homeopathy: New Delhi, India, 1978; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Wang, W.; Fang, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, W. United State Patent: Agarofuan Derivatives, Their Preparation, Pharmaceutical Composition Containing Them and Their Use as Medicine. U.S. Patent 6486201b1, 26 November 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, I.A.S. The role of fungi in the origin of oleoresin deposits (agaru) in the wood of Aquilaria agallocha Roxb. Bano Biggyan Patrika 1977, 6, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pojanagaroon, S.; Kaewrak, C. Mechanical methods to stimulate aloes wood formation in Aquilaria crassna Pierre ex h.lec. (kritsana) trees. Acta Hortic. 2005, 676, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirth, F.; Rockhil, W.W. Chau Ju-Kua: His Work on the Chinese and Arab Trade in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, Entitled Chu-Fan-Chi; Imperial Academy of Sciences: St. Petersberg, FL, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, M.; Okimoto, K.I.; Yagura, T.; Honda, G.; Kiuchi, F.; Shimada, Y. Induction of sesquiterpenoid production by methyl jasmonate in Aquilaria sinensis cell suspension culture. J. Essen. Oil Res. 2005, 17, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Q.; Yang, Y.; Xue, J.; Wei, J.H.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.J. Comparison of compositions and antimicrobial activities of essential oils from chemically stimulated agarwood, wild agarwood and healthy Aquilaria sinensis (Lour.) Gilg trees. Molecules 2011, 16, 4884–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Meng, H.; Gao, Z.H.; Chen, W.P.; Feng, J.D.; Chen, H.Q. An Agarwood Induction Agent and Its Preparation Method. Patent CN101731282B, 21 March 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Wei, J.H.; Meng, H.; Gao, Z.h.; Xu, Y.h. Hydrogen peroxide induces vessel occlusions and stimulates sesquiterpenes accumulation in stems of Aquilaria sinensis. Plant Growth Regul. 2014, 72, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faizal, A.; Esyanti, R.R.; Aulianisa, E.N.; Santoso, E.; Turjaman, M. Formation of agarwood from Aquilaria malaccensis in response to inoculation of local strains of Fusarium solani. Trees 2017, 31, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.L.; Guo, S.X.; Fu, S.B.; Xiao, P.G.; Wang, M.L. Effects of inoculating fungi on agilawood formation in Aquilaria sinensis. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2013, 58, 3280–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Liu, Y.Y.; Yang, Y.; Feng, J.; Liu, P.W.; Sui, C.; Wei, J.H. Trunk surface agarwood-inducing technique with Rigidoporus vinctus: An efficient novel method for agarwood production. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamuli, P.; Boruah, P.; Nath, S.C.; Samanta, R. Fungi from disease agarwood tree (Aquilaria agallocha Roxb): Two new records. Adv. For. Res. India 2000, 22, 182–187. [Google Scholar]

- Tabata, Y.; Widjaja, E.; Mulyaningsih, T.; Parman, I.; Wiriadinata, H.; Mandang, Y.I.; Itoh, T. Structural survey and artificial induction of aloeswood. Wood Res. 2003, 90, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tamuli, P.; Boruah, P.; Nath, S.C.; Leclercq, P. Essential oil of eaglewood tree: A product of pathogenesis. J. Essent. Oil. Res. 2005, 17, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, G.; Putridan Juliarni, A.L. Acremonium and methyl-jasmonate induce terpenoid formation in agarwood tree (Aquilaria crassna). In Proceedings of the Makalahdi Presenta Sikandalam 3rd Asian Conference on Crop Protection, Jogyakarta, Indonesia, 22–24 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Budi, S.; Santoso, E.; Wahyudi, A. Identification of potential types of fungi on establishment agarwood stem of Aquilaria spp. Jurnal Silvikultur Tropika 2010, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Santoso, E.; Irianto, R.S.B.; Turjaman, M.; Sitepu, I.R.; Santosa, S.; Najmulah; Yani, A.; dan Aryanto. Gaharu-Producing Tree Induction Technology. In Development of Gaharu Production, Technology; Turjaman, M., Ed.; Ministry of Forestry: Bogor, Indonesia, 2011; pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Iskandar, D.; Suhendra, A. Uji inokulasi Fusarium sp. Untuk produksi gaharu pada budidaya A. beccariana. J. Sains dan Teknol. Indones. 2012, 14, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, R.; Jong, P.L.; Kamziah, A.K. Fungal inoculation induces agarwood in young Aquilaria malaccensis trees in the nursery. J. For. Res. 2014, 25, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisdayani, L.; Anna, N.; Siregar, E.B.M. Isolation and identifying of fungi from the stem of agarwood (Aquilaria malaccensis Lamk.) was had been inoculation. Peronema For. Sci. 2015, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Triadiati, T.; Carolina, D.A.; Miftahudin. Induksi pembentukan gaharu menggunakan berbagai media tanam dan cendawan Acremonium sp. dan Fusarium sp. pada Aquilaria crassna. J. Sumberd. Hayati 2016, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novriyanti, E.; Santosa, E.; Syafii, W.; Turjaman, M.; Sitepu, I.R. Anti-fungal activity of wood extract of Aquilaria crassna Pierre ex Lecomte against agarwood-inducing fungi, Fusarium solani. Indones. J. For. Res. 2010, 7, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.R. The nature of ‘Agaru’ formation. Sci. Cult. 1938, 4, 89–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, S.R. Agaru production by fungal inoculation in Aquilaria agallocha trees in Assam. In Proceedings of the 30th Indian Scientific Congress, Kolkata, India, 2–8 January 1943. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, B. On the formation and development of agaru in Aquilaria agallocha. Sci. Cult. 1952, 18, 240–243. [Google Scholar]

- Sadgopal, V.B. Exploratory studies in the development of essential oils and their constituents in aromatic plants. Part I. Oil of agarwood. Soap Perfum. Cosmet. 1960, 33, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hawksworth, D.L.; Gibson, I.A.S. Phialophora parasitica. In C.M.I. Descriptions of Pathogenic Fungi and Bacteria; Commonwealth Mycological Institute: Kew, UK, 1976; p. 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, E. Pembentukan gaharu dengan cara inokulasi. In Proceedings of the Makalah Diskusi Hasil Penelitian Dalam Menunjang Pemanfaatan Hutan Yang Lestari, Bogor, Indonesia, 11–12 March 1996; Turjaman, M., Ed.; Pusat Litbang Hutan dan Konservasi Alam: Bogor, Indonesia, 1996; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, L.; Guo, S. Endophytic fungi from Dracaena cambodiana and Aquilaria sinensis and their antimicrobial activity. Afri. J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 731–736. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F.; Mei, W.L.; Wu, J.; Dai, H.F. GC-MS analysis of Volatile constituents from Chinese eaglewood produced by artificial methods. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2010, 33, 222–225. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, R.; Jong, P.L.; Zali, M.S. Fungal diversity in wounded stems of Aquilaria malaccensis. Fungal Divers. 2010, 43, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.C.; Li, D.L.; Chen, Y.C.; Zhang, W.M. A new isofuranonaphthalenone and benzopyrans from the endophytic fungus Nodulisporium sp. A4 from Aquilaria sinensis. Helv. Chim. Acta 2010, 93, 920–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.L.; Guo, S.X.; Xiao, P.G. Antitumor and antimicrobial activities of endophytic fungi from medicinal parts of Aquilaria sinensis. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. B (Biomed. Biotechnol.) 2011, 12, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.H.; Yan, J.; Wei, X.Y.; Li, D.L.; Zhang, W.M.; Tan, J.W. A novel sesquiterpene alcohol from Fimetariella rabenhorstii, an endophytic fungus of Aquilaria sinensis. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2011, 6, 763–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.L.; Chen, Y.C.; Tao, M.H.; Li, H.H.; Zhang, W.M. Two new octahydro naphthalene derivatives from Trichoderma spirale, an endophytic fungus derived from Aquilaria sinensis. Helv. Chim. Acta 2012, 95, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.L.; Wang, C.L.; Guo, S.X.; Yang, L.; Xiao, P.G.; Wang, M.L. Evaluation of fungus-induced agilawood from Aquilaria sinensis in China. Symbiosis 2013, 60, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premalatha, K.; Kalra, A. Molecular phylogenetic identification of endophytic fungi isolated from resinous and healthy wood of Aquilaria malaccensis, a red listed and highly exploited medicinal tree. Fungal Ecol. 2013, 6, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.L.; Chen, Y.C.; Pan, Q.L.; Tao, M.H.; Zhang, W.M. A new eudesmane sesquiterpene from Nigrospora oryzae, an endophytic fungus of Aquilaria sinensis. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2014, 8, 330–333. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Han, X.M.; Wei, J.H.; Xue, J.; Yang, Y.; Liang, L.; Li, X.J.; Guo, Q.M.; Xu, Y.H.; Gao, Z.H. Compositions and antifungal activities of essential oils from agarwood of Aquilaria sinensis (Lour.) Gilg induced by Lasiodiplodia theobromae (Pat.) Griffon; Maubl. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2014, 25, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunarsih, F.; Rahayu, G.; Hidayat, I. Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis of Indonesian Fusarium Isolates from Different Lifestyles, based on ITS Sequence Data. Plant Pathol. Quar. 2015, 5, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.K.; Cuong, L.H.; Hang, T.T.N.; Luyen, N.D.; Huong, L.M. Biological characterization of fungal endophytes isolated from agarwood tree Aquilaria crassna pierre ex lecomte. Vietnam. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 14, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huang, J.Q.; Liao, Y.C.; Chen, H.J.; Zhang, Z. Chemical solution is an efficient method to induce the formation of 2-(2-phenylethyl) chromone derivatives in Aquilaria sinensis. Phytochem. Lett. 2017, 19, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Dehingia, M.; Talukdar, N.C.; Khan, M. Chemometric analysis reveals links in the formation of fragrant bio-molecules during agarwood (Aquilaria malaccensis) and fungal interactions. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.P.; Zheng, K.; Liu, Y.R.; Ma, H.F.; Xiao, Z.Y. Effects of two fungi on xylem tissue structure of white wood incense. West. For. Sci. 2018, 47, 141–144. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.Q.; Guo, H.; Chen, X.Y.; Zhong, Z.J.; Li, H.H.; Zhang, W.M.; Gao, X.X. Analysis of secondary metabolites of rice black spore A8 and its induced artificial agarwood. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2018, 41, 1662–1667. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Nasution, A.A.; Siregar, U.J.; Miftahudin; Turjaman, M. Identification of chemical compounds in agarwood-producing species Aquilaria malaccensis and Gyrinops versteegii. J. For. Res. 2019, 31, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Gu, L.P.; Xiao, Z.Y.; Ma, H.F. Study on the effects of Fusarium oxysporum and Dichromium cocoanum on the chemical composition of balsam wood xylem. For. Investig. Plan. 2019, 44, 27–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S.; Thomas, S.; Mochahari, D.; Kharnoir, S. Isolation of endophytic fungi from juvenile Aquilaria malaccensis and their antimicrobial properties. J. Trop. For. Sci. 2020, 32, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; He, R.; Cui, Y.; Li, Y.; Ge, X. Saprophytic Bacillus Accelerates the Release of Effective Components in Agarwood by Degrading Cellulose. Molecules 2022, 27, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Endophytic Fungi Species | Endophytic Fungi Family | Agarwood-Producing Trees | Country | References |

| Acremonium sp. | Incertae sedis | Aquilaria crassna | N/A | [56] |

| Acremonium sp. | Incertae sedis | Aquilaria microcarpa | Malaysia | [50] |

| Aspergillus niger | Aspergillaceae | Gyrinops walla | Sri Lanka | [28] |

| Aspergillus sp. | Aspergillaceae | Aquilaria sp. | India | [58] |

| Botryodyplodis | N/A | Aquilaria sp. | India | [58] |

| Botryosphaeria dothidea | Botryosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sp. | India | [58] |

| Botryosphaeria sp. | Botryosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [32] |

| Chaetomium globosum | Chaetomiaceae | Aquilaria agallocha | India | [47] |

| Chaetomium globosum | Chaetomiaceae | Aquilaria agallocha | N/A | [49] |

| Cladosporium sp. | Cladosporiaceae | Aquilaria agallocha | N/A | [61] |

| Diplodia sp. | Botryosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sp. | India | [58] |

| Epicoccum granulatum | Didymellaceae | Aquilaria agallocha | India | [60] |

| Fusarium bulbigenium | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | [63] |

| Fusarium lateritium | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | [63] |

| Fusarium moniliforme | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | [51] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria agallocha | India | [47] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria agallocha | N/A | [49] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [74] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [79] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | [63] |

| Fusarium sambucinum | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | [51] |

| Fusarium solani | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria malaccensis | Indonesia | [44] |

| Fusarium solani | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria malaccensis | Indonesia | [81] |

| Fusarium solani | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [24] |

| Fusarium solani | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [82] |

| Fusarium solani | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | [51] |

| Fusarium solani | Nectriaceae | Gyrinops versteegii | Indonesia | [81] |

| Fusarium solani | Nectriaceae | Gyrinops versteegii | Indonesia | [26] |

| Fusarium solani | Nectriaceae | Gyrinops walla | Sri Lanka | [28] |

| Fusarium sp. | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria beccariana | N/A | [53] |

| Fusarium sp. | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria crassna | N/A | [56] |

| Fusarium sp. | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria malaccensis | India | [78] |

| Fusarium sp. | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria malaccensis | N/A | [55] |

| Fusarium sp. | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria microcarpa | N/A | [52] |

| Fusarium sp. | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [32] |

| Fusarium sp. | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [77] |

| Fusarium sp. | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sp. | Indonesia | [48] |

| Fusarium sp. | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sp. | Sumatra island | [48] |

| Fusarium sp. | Nectriaceae | Gyrinops versteegii | Indonesia | [48] |

| Fusarium tricinctum | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sp. | N/A | [51] |

| Lasiodiplodia sp. | Botryosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [45] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Botryosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [29] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Botryosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [74] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Botryosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [24] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Botryosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [77] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Botryosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [79] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Botryosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [82] |

| Melanotus flavolivens | Strophariaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [30] |

| Melanotus flavolivens | Strophariaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [65] |

| Nigrospora oryzae | Incertae sedis | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [80] |

| Paraconiothyrium variabile | Didymosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [71] |

| Rigidoporus vinctus | Meripilaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [46] |

| Torula sp. | Torulaceae | Aquilaria agallocha | N/A | [61] |

| Unidentified five fungi belonging to the Deuteromycetes and Ascomycetes groups | N/A | Aquilaria malaccensis | Malaysia | [54] |

| Xylaria sp. | Xylariaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | China | [45] |

| Endophytic Fungi Species | Endophytic Fungi Family | Isolation Source | Bioactivity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Botryosphaeria rhodina | Botryosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Cephalosporium sp. | Incertae sedis | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Cladophialophora sp. | Herpotrichiellaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Cladosporium edgeworthrae | Cladosporiaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Cladosporium sp. | Cladosporiaceae | Aquilaria malaccensis | Antibacterial effect against Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis | [83] |

| Cladosporium tenuissimum | Cladosporiaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [68] |

| Colletotrichum sp. | Glomerellaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Coniothyrium nitidae | Coniothyriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [68] |

| Diaporthe sp. | Diaporthaceae | Aquilaria subintegra | Excellent antioxidant capacity | [31] |

| Epicoccum nigrum | Didymellaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [68] |

| Epicoccum sp. | Didymellaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Fusarium equiseti | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [68] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [68] |

| Fusarium solani | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [68] |

| Fusarium sp. | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Fusarium verticillioides | Nectriaceae | Aquilaria crassna | Antimicrobial activity | [76] |

| Geotrichum candium | Dipodascaceae | Aquilaria crassna | Antimicrobial activity | [76] |

| Geotrichum sp. | Dipodascaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Glomerularia sp. | Platygloeaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Gonytrichum sp. | Chaetosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Guignardia manqiferae | Phyllostictaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Hypocrea lixii | Hypocreaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [68] |

| Lasiodiplodia theobromae | Botryosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [68] |

| Leptosphaerulina chartarum | Didymellaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [68] |

| Monilia sp. | Sclerotiniaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Mortierella sp. | Mortierellaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Mycelia sterilia sp. | N/A | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Nemania aquilariae | Xylariaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antibacterial and antimicrobial | [25] |

| Ovulariopsis sp. | Erysiphaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Paraconiothyrium variabile | Didymosphaeriaceae | Aquilaria sinensi | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [68] |

| Penicillium sp. | Aspergillaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Phaeoacremonium rubrigenum | Togniniaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [68] |

| Phoma herbarum | Didymellaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [68] |

| Pleospora sp. | Pleosporaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Rhinocladiella sp. | Herpotrichiellaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial activity | [64] |

| Rhizomucor variabilis | Lichtheimiaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [68] |

| Xylaria mali | Xylariaceae | Aquilaria sinensis | Antimicrobial and antitumor activity | [32] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, T.-Y.; Dao, C.-J.; Mapook, A.; Stephenson, S.L.; Elgorban, A.M.; Al-Rejaie, S.; Suwannarach, N.; Karunarathna, S.C.; Tibpromma, S. Diversity and Biosynthetic Activities of Agarwood Associated Fungi. Diversity 2022, 14, 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14030211

Du T-Y, Dao C-J, Mapook A, Stephenson SL, Elgorban AM, Al-Rejaie S, Suwannarach N, Karunarathna SC, Tibpromma S. Diversity and Biosynthetic Activities of Agarwood Associated Fungi. Diversity. 2022; 14(3):211. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14030211

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Tian-Ye, Cheng-Jiao Dao, Ausana Mapook, Steven L. Stephenson, Abdallah M. Elgorban, Salim Al-Rejaie, Nakarin Suwannarach, Samantha C. Karunarathna, and Saowaluck Tibpromma. 2022. "Diversity and Biosynthetic Activities of Agarwood Associated Fungi" Diversity 14, no. 3: 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14030211

APA StyleDu, T.-Y., Dao, C.-J., Mapook, A., Stephenson, S. L., Elgorban, A. M., Al-Rejaie, S., Suwannarach, N., Karunarathna, S. C., & Tibpromma, S. (2022). Diversity and Biosynthetic Activities of Agarwood Associated Fungi. Diversity, 14(3), 211. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14030211