Bats of Bangladesh—A Systematic Review of the Diversity and Distribution with Recommendations for Future Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

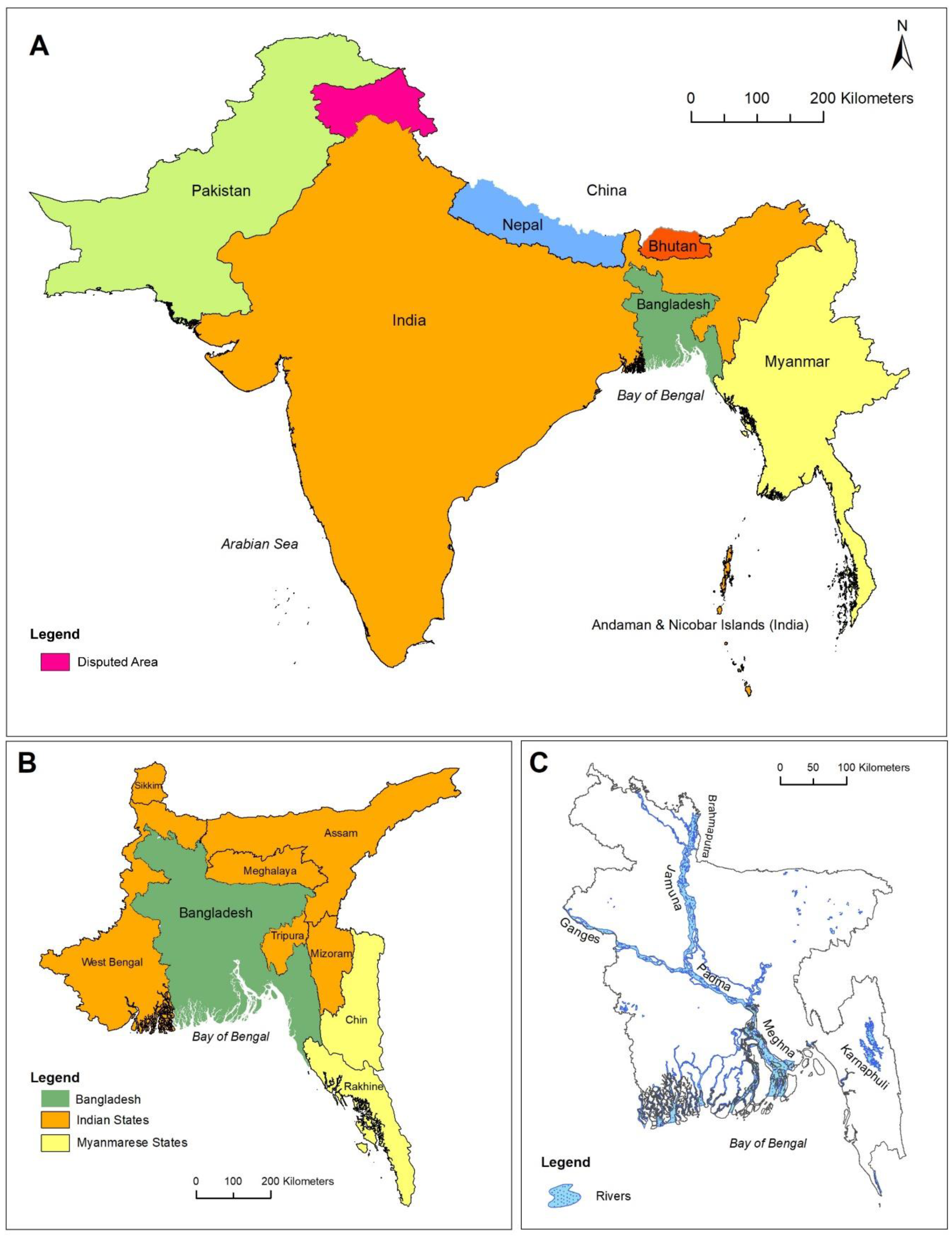

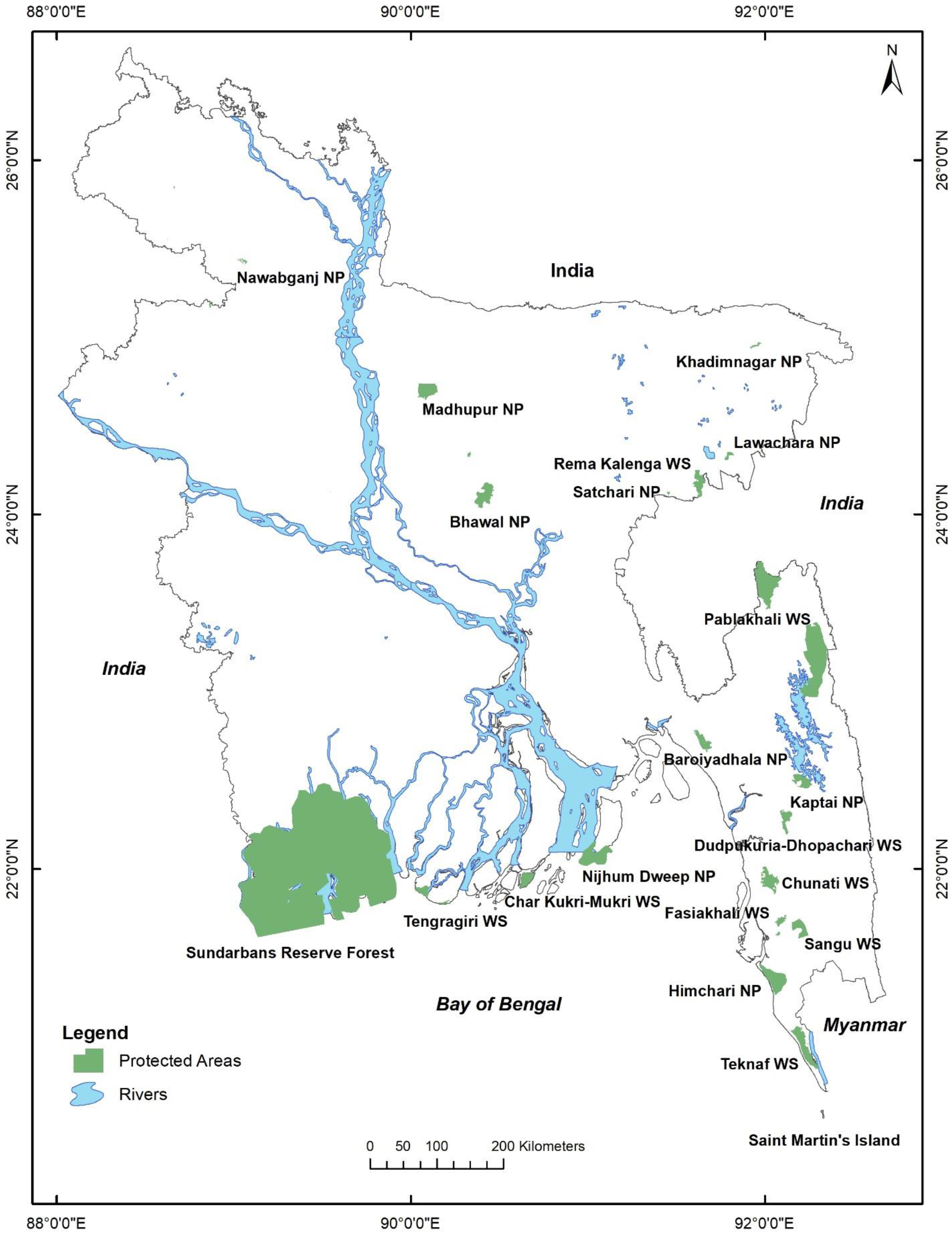

2.1. Study Countries and Regions

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Extraction from Records

- (1)

- Locality information with latitude and longitude (fine-scale distribution) given in the record.

- (2)

- Locality information with latitude and longitude estimated from capture site descriptions. For many records, capture coordinates were not given, but the capture area, forest, sub-district, district, or a definite direction were listed (e.g., Netrokona, Modhupur forest, Mawsmai cave, 30 km north of Dhaka). We used Google Maps to identify the mentioned area or measured distance (e.g., 30 km north of Dhaka) and then selected a coordinate for the locality (fine-scale distribution).

- (3)

- State-wide distributions (coarse-scale distribution) if no specific coordinates or locality descriptions were provided but the state was named (e.g., Meghalaya, Rakhine).

- (4)

- Catalog number if the data were extracted from a museum database or GBIF.

- (5)

- Capture methods (e.g., mist nets, harp traps).

- (6)

- Basis of records, following Darwin Core terms. Specifically, whether a record was based on a preserved specimen (Darwin Core term “PreservedSpecimen”), tissues or organs (skulls, jaws) taken from an individual and preserved (MaterialSample), still image (“MachineObservation”) or human observation (“HumanObservation). However, any information related to body measurement, that did not fall under the Darwin Core basis of record, was referred to as measurement or fact (Darwin Core term “MeasurementOrFact”) [58].

- (7)

- Habitat type where the species was captured. If this was not mentioned, we collected required habitat information (e.g., caves, tropical dry forest, deciduous forest, evergreen/semi-evergreen/mixed evergreen forest, bamboo forest, mangrove forest, agricultural lands, human settlements) from the IUCN Red List species assessment [2].

2.4. Inferring Possible Occurrence of Species in Bangladesh

2.5. Occurrence Maps

3. Results

4. Discussion

| Families and Species | Confirmed Records (See Table S1) | Species Reported in the Literature | Red List Threat Category (IUCN 2022) [2] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Museum Records | GBIF | Literature Records | IUCN Red List 2022 [2] | Srinivasulu et al., 2021 [4] | Khan 2018 [7] | IUCN Bangladesh 2015 [9] | Srinivasulu and Srinivasulu 2012 [29] | Sarker and Sarker 2005 [27] | Molur et al., 2002 [25] | Khan 2001 [10] | |||

| Pteropodidae | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Pteropus medius Temminck, 1825 | 1A | 1A | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC |

| 2 | Rousettus leschenaultii (Desmarest, 1820) | 1A | 1B | 1B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NT |

| 3 | Cynopterus sphinx (Vahl, 1797) | 1A | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |

| 4 | Cynopterus brachyotis (Mȕller, 1838) | 1A | Y | LC | |||||||||

| 5 | Eonycteris spelaea (Dobson, 1871) | 1B | Y | Y | LC | ||||||||

| 6 | Megaerops niphanae Yenbutra & Felten, 1983 | 1A | Y | LC | |||||||||

| 7 | Macroglossus sobrinus K. Andersen, 1911 | 1A | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||||||

| Rhinolophidae | |||||||||||||

| 8 | Rhinolophus pusillus Temminck, 1834 | 1A | Y | Y | LC | ||||||||

| 9 | Rhinolophus lepidus Blyth, 1844 | 1B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | ||

| 10 | Rhinolophus luctus Temminck, 1834 | 1A | 1B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | ||||

| 11 | † Rhinolophus subbadius Blyth, 1844 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||

| 12 | * Rhinolophus pearsonii Horsfield, 1851 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||||

| 13 | * Rhinolophus macrotis Blyth, 1844 | Y | Y | Y | LC | ||||||||

| 14 | Rhinolophus affinis Horsfield, 1823 | 1B | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||||||

| Hipposideridae | |||||||||||||

| 15 | Hipposideros cineraceus Blyth, 1853 | 1B | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||||||

| 16 | Hipposideros lankadiva Kelaart, 1850 | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||

| 17 | Hipposideros larvatus (Horsfield, 1823) | 1B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | ||

| 18 | § Hipposideros galeritus Cantor, 1846 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||||

| 19 | Hipposideros pomona K. Andersen, 1918 | 1A | Y | Y | Y | EN | |||||||

| 20 | Coelops frithii Blyth, 1848 | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NT | ||

| Megadermatidae | |||||||||||||

| 21 | Lyroderma lyra (E. Geoffroy, 1810) | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | ||

| 22 | Megaderma spasma (Linnaeus, 1758) | 1B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||

| Emballonuridae | |||||||||||||

| 23 | Saccolaimus saccolaimus (Temminck, 1838) | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | ||

| 24 | Taphozous longimanus Hardwicke, 1825 | 1A | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |

| 25 | * Taphozous melanopogon Temminck, 1841 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | ||||

| Molossidae | |||||||||||||

| 26 | Mops plicatus (Buchannan, 1800) | 1B | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | ||||||

| 27 | † Tadarida aegyptiaca (E. Geoffroy, 1818) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | ||||

| Rhinopomatidae | |||||||||||||

| 28 | * Rhinopoma hardwickii Gray, 1831 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||||

| 29 | § Rhinopoma microphyllum (Brȕnnich, 1782) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||||

| Vespertilionidae | |||||||||||||

| 30 | Scotophilus heathii (Horsfield, 1831) | 1A | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |

| 31 | Scotophilus kuhlii Leach, 1821 | 1A | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |

| 32 | * Scotozous dormeri Dobson, 1875 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||

| 33 | Pipistrellus pipistrellus (Schreber, 1774) | 1A | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||||||

| 34 | Pipistrellus javanicus (Gray, 1838) | 1A | 1A | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||

| 35 | Pipistrellus coromandra (Gray, 1838) | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | ||

| 36 | Pipistrellus tenuis (Temminck, 1840) | 1A | 1A | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC |

| 37 | Pipistrellus ceylonicus (Kelaart, 1852) | 1B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||

| 38 | †† Hypsugo savii (Bonaparte, 1837) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||||

| 39 | † Hypsugo affinis (Dobson, 1871) | Y | LC | ||||||||||

| 40 | Kerivoula picta (Pallas, 1767) | 1B | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NT | ||

| 41 | * Kerivoula papillosa (Temminck, 1840) | Y | Y | Y | LC | ||||||||

| 42 | † Eptesicus pachyotis (Dobson, 1871) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | ||||

| 43 | * Scotomanes ornatus (Blyth, 1851) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||||

| 44 | * Myotis formosus (Hodgson, 1835) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NT | |||||

| 45 | Hesperoptenus tickelli (Blyth, 1851) | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | |||||

| 46 | Tylonycteris pachypus (Temminck, 1840) | 1A | Y | Y | Y | Y | LC | ||||||

| Confirmed 1A = 22, 1B = 9. Total 31 | Species reported in literature based on 1A, 1B and expert opinion = 46 | ||||||||||||

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statements

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simmons, N.B.; Cirranello, A.L. Bat Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Database. Available online: https://batnames.org (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- IUCN 2022. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2021-3. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Bates, P.J.J.; Harrison, D.L. Bats of the Indian Subcontinent; Harrison Zoological Museum Publication: Sevenoaks, Kent, UK, 1997; p. 258. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasulu, C.; Srinivasulu, A.; Srinivasulu, B. Checklist of the Bats of South Asia (v1.4). Available online: https://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/checklists/bats/southasia (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Stanford, C.B. The Capped Langur in Bangladesh: Behavioral Ecology and Reproductive Tactics; Karger Medical and Scientific Publishers: Basel, Switzerland, 1991; Volume 26, pp. 1–179. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.R. Wildlife of Bangladesh—A Checklist; Dhaka University: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1982; pp. iv+174. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.M.H. Photographic Guide to the Wildlife of Bangladesh; Arannayk Foundation: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2018; p. 488. [Google Scholar]

- Azam, M.G.; Rahman, M.M. Assessing Spatial Vulnerability of Bangladesh to Climate Change and Extreme: A Geographic Information System Approach. Res. Sq. 2022, 11, 342–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN Bangladesh. Mammals. In Red Book of Bangladesh; International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2015; Volume 2, pp. i-xvi+232. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.R. Status and Distribution of Bats in Bangladesh with Notes on Their Ecology. Zoos’ Print J. 2001, 16, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Kalam, M.A.; Alam, M.; Shano, S.; Faruq, A.A.; Hossain, M.S.; Islam, M.N.; Khan, S.A.; Islam, A. Understanding the Community Perceptions and Knowledge of Bats and Transmission of Nipah Virus in Bangladesh. Animals 2020, 10, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, N.; Asaduzzaman, M.; Mandal, U.K.; Rimi, N.A.; Gurley, E.S.; Rahman, M.; Garcia, F.; Zimicki, S.; Sultana, R.; Luby, S.P. Hunting for Human Consumption in Bangladesh. Ecohealth 2020, 17, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Hasan, M.K.; Feeroz, M.M. Diversity and Morphometry of Chiropteran Fauna in Jagangirnagar University Campus, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Zool. 2015, 43, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kunz, T.H.; de Torrez, E.B.; Bauer, D.; Lobova, T.; Fleming, T.H. Ecosystem Services Provided by Bats. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1223, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchannan, F. Description of The Vespertilio plicatus. Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. 1800, 5, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Blyth, E. Description of Three Indian Species of Bat, of the Genus Taphozous. J. Asiafic Soc. Bengal 1841, 10, 971–977. [Google Scholar]

- Blyth, E. Notice of a Collection of Mammalia, Birds, and Reptiles Procured at or Near the Station of Cherrapunji in The Khasia Hills, North of Sylhet. J. Asiafic Soc. Bengal 1852, 20, 517–524. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasulu, C.; Srinivasulu, B. A Review of Chiropteran Diversity of Bangladesh. BAT Net-CCINSA Newsl. 2005, 6, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi, M.S.U. Checklist of Mammals of Pakistan with Particular Reference to the Mammalian Collection in the British Museum (Natural History), London. Biologia 1961, 7, 93–225. [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed, S.K. Bats of Bangladesh. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh, Unpublished work. 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.K. Bats of Bangladesh (with Notes on Field Observation). M.Sc. Thesis, Dhaka University, Dhaka, Bangladesh, Unpublished work. 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Husain, K.Z. Bats of Bangladesh. J. Asiat. Soc. Bangladesh Sci. 1982, 8, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, S.U.; Sarker, N.J. Wildlife of Bangladesh (a Systematic List with Status, Distribution and Habitat); The Rico Printers: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1988; pp. xix+59. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN Bangladesh. Red Book of Threatened Mammals of Bangladesh; International Union for Conservation of Nature: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2000; p. 71. [Google Scholar]

- Molur, S.; Marimuthu, G.; Srinivasulu, C.; Mistry, S.; Hutson, A.M.; Bates, P.J.J.; Walker, S.; Padmapriya, K.; Binupriya, A.R. Status of South Asian Chiroptera: Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) Workshop Report; Zoo Outreach Organization/CBSG-South Asia: Coimbatore, India, 2002; p. 317. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, S.U.; Sarker, N.J. Habitat Use and Conservation Issues of Bats of Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the 5th European Bat Detector Workshop, Foret de Trncais, France, 21–25 August 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, S.U.; Sarker, N.J. Bats of Bangladesh with Notes on the Status, Distribution and Habitat. BAT Net-CCINSA Newsl. 2005, 6, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasulu, C.; Racey, P.A.; Mistry, S. A Key to the Bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) of South Asia. J. Threat. Taxa 2010, 2, 1001–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasulu, C.; Srinivasulu, B. South Asian Mammals: Their diversity, Distribution and Status; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. xi+467. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.A.R. Wildlife of Bangladesh: Checklist and Guide; Chayabithi: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2015; p. 568. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.N.; Shaikat, A.M.; Islam, K.M.F.; Shil, S.K.; Akter, S.; Rahman, M.M.; Hassan, M.M.; Islam, A.; Khan, S.A.; Furey, N. First record of Ratanaworabhans’s Fruit Bat Megaerops niphanae Yenbutra & Felten, 1983 (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) from Bangladesh. J. Threat. Taxa 2015, 7, 7821–7824. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, A.; Hasan, M.K.; Feeroz, M.M. Cryptic Rhinolophus pusillus Temminck, 1834 (Chiroptera, Rhinolophidae): A New Distribution Record from the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. Check List 2017, 13, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saha, A.; Hasan, M.K.; Feeroz, M.M. Recent Record of Javan pipistrelle (Pipistrellus javanicus, Grey 1838) from Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), Bangladesh. Bat Res. Conserv. 2017, 10, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, A.; Hasan, M.K.; Feeroz, M.M. Andersen’s Leaf-nosed Bat (Hipposideros pomona) is Still Living in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh. Mammalia 2018, 82, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, M.; Saha, A.; Feeroz, M.M.; Hasan, M.K. Greater Long-nosed Bat Macroglossus sobrinus: A New Distribution Record in Bangladesh. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 2019, 116, 72–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, T.; Hasan, S.; Naher, H.; Muzaffar, S.B. Record of Great Woolly Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus luctus, Temmick 1834) in Northeast Bangladesh. Bat Res. Conserv. 2020, 13, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasulu, C. South Asian Mammals: An Updated Checklist and Their Scientific Names, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; p. 374. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, J.J.M.; Santos, J.C.; Urso-Guimaraes, M.V. On the Use of Photography in Science and Taxonomy: How Images Can Provide a Basis for Their Own Authentication. Bionomina 2017, 12, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, C.; Ahyong, S.T.; Boyko, C.B.; D’Udekem D’Acoz, C.; Noreña, C.; Macpherson, E. Images are Not and Should Not be Type Specimens: A Rebuttal to Garraffoni & Freitas. Zootaxa 2017, 4269, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Reza, A.A.; Hasan, M.K. Forest Biodiversity and Deforestation in Bangladesh: The Latest Update. In Forest Degradation Around the World; Suratman, M.N., Latif, Z.A., De Oliveira, G., Brunsell, N., Shimabukuro, Y., Santos, C.A.C.D., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, K.R.; Weil, R.R. Land Use Effects on Soil Quality in a Tropical Forest Ecosystem of Bangladesh. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2000, 79, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.S.; Pasha, S.V.; Jha, C.S.; Diwakar, P.G.; Dadhwal, V.K. Development of National Database on Long-term Deforestation (1930–2014) in Bangladesh. Glob. Planet. 2016, 139, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zzaman, R.U.; Nowreen, S.; Billah, M.; Islam, A.S. Flood Hazard Mapping of Sangu River Basin in Bangladesh Using Multi-criteria Analysis of Hydro-geomorphological Factors. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2021, 14, e12715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Islam, R.I.; Rahman, M.S.; Ibrahim, M.; Shamsuzzoha, M.; Khanam, R.; Zaman, A.K.M.M. Analysis of Land Use and Land Cover Changing Patterns of Bangladesh Using Remote Sensing Technology. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 17, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, K.; Gurung, D.R. Land Cover Change in Bangladesh—A Knowledge Base Classification Approach. In Grazer Schriften der Geographie und Raumforschung, Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on High Mountain Remote Sensing Cartography, Kathmandu, Nepal, 8–11 September; Kaufmann, V., Sulzer, W., Eds.; Karl-Franzens University of Graz: Graz, Austria, 2010; pp. 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sultana, M.S.; Gazi, M.Y.; Mia, M.B. Multiple Indices Based Agricultural Drought Assessment in the Northwestern Part of Bangladesh Using Geospatial Techniques. Environ. Chall. 2021, 4, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, S.G.; Platt, K.; Khaing, L.L.; Yu, T.T.; Soe, M.M.; Nwe, S.S.; Naing, T.Z.; Rainwater, T.R. Heosemys depressa in the Southern Chin Hills of Myanmar: A significant Range Extension and Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 2014, 13, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, N.C.; Chennaiah, G.C. Land-use and Land-cover Mapping and Change Detection in Tripura Using Satellite LANDSAT Data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1985, 6, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, J.; Majumder, K.; Bhattacharjee, P.P.; Agarwal, B.K. Inventory of Mammals in Protected Reserves and Natural Habitats of Tripura, Northeast India with Notes on Existing Threats and New Records of Large Footed Mouse-eared Bat and Greater False Vampire Bat. Check List 2015, 11, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neha, S.A.; Khatun, U.H.; Ul Hasan, M.A. Resource Partitioning and Niche Overlap between Hoolock Gibbon (Hoolock hoolock) and Other Frugivorous Vertebrates in a Tropical Semi-evergreen Forest. Primates 2021, 62, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, J.; Raman, T.R.S. Shifting Agriculture Supports More Tropical Forest Birds than Oil Palm or Teak Plantations in Mizoram, northeast India. Ornithol. Appl. 2016, 118, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, N.; Garkoti, S.C. Tree Species composition, Diversity, and Regeneration Patterns in Undisturbed and Disturbed Forests of Barak Valley, South Assam, India. Intl. J. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2011, 37, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Haridarshan, K.; Rao, R.R. Forest Flora of Meghalaya; Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh: Dehra Dun, India, 1985; p. 937. [Google Scholar]

- Saikia, U.; Thabah, A.; Chachula, O.M.; Ruedi, M. The Bat Fauna of Meghalaya, Northeast India: Diversity and Conservation. In Indian Hotspots; Sivaperuman, C., Venkataraman, K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 263–286. [Google Scholar]

- Sathyakumar, S.; Bashir, T.; Bhattacharya, T.; Poudyal, K. Assessing Mammal Distribution and Abundance in Intricate Eastern Himalaya Habitats of Khangchendzonga, Sikkim, India. Mammalia 2011, 75, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, J.K. Mammals of Kalimpong Hills, Darjeeling District, West Bengal, India. J. Threat. Taxa 2012, 4, 3103–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, J.; Bloom, D.; Guralnick, R.; Blum, S.; Döring, M.; Giovanni, R.; Robertson, T.; Vieglais, D. Darwin Core: An Evolving Community-Developed Biodiversity Data Standard. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, N.B. Order Chiroptera. In Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd ed.; Wilson, D.E., Reeder, D.M., Eds.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2005; p. 2142. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanin, A.; Khouider, S.; Gembu, G.; Goodman, S.M.; Kadjo, B.; Nesi, N.; Pourrut, X.; Nakoune, E.; Bonillo, C. The Comparative Phylogeography of Fruit Bats of the Tribe Scotonycterini (Chiroptera, Pteropodidae) Reveals Cryptic Species Diversity Related to African Pleistocene Forest Refugia. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2015, 338, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baki, M.A.; Al-Razi, H.; Alam, S.M.I. Mating Behaviour of the Indian Flying Fox (Chiroptera) in Southern Bangladesh. Tabrobanica 2015, 7, 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Razi, H.; Shahadat, O.; Hasan, A.U.; Neha, S.A. On the Roosting and Mating of Saccolaimus saccolaimus (Chiroptera) in Bangladesh. Taprobanica 2015, 7, 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.K.; Feeroz, M.M.; Datta, A.K.; Saha, A.; Ahmed, T. Indian Flying Fox (Pteropus giganteus) roosts in north Bengal of Bangladesh. In The Festschrift on the 50th Anniversary of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; Ali, M.S., Feeroz, M.M., Naser, M.N., Eds.; IUCN Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shihan, T.R. Roost of Indian Flying Fox Pteropus giganteus in Badurtola, Chuadanga District, Bangladesh. Small Mammal. 2014, 5, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shihan, T.R. Unexpected Death of Indian Flying Foxes Pteropus giganteus in Jahangirnagar University Campus, Savar, Bangladesh. Small Mammal. 2014, 6, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Homaira, N.; Rahman, M.; Hossain, M.J.; Epstein, J.H.; Sultana, R.; Khan, M.S.U.; Podder, G.; Nahar, K.; Ahmed, B.; Gurley, E.S.; et al. Nipah Virus Outbreak with Person-to-Person Transmission in a District of Bangladesh. Epidemol. Infect. 2010, 138, 1630–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, A.; Mikolon, A.; Mikoleit, M.; Ahmed, D.; Khan, S.U.; Sharker, M.A.Y.; Hossain, M.J.; Islam, A.; Epstein, J.H.; Zeidner, N.; et al. Isolation of Salmonella Virchow from a Fruit Bat (Pteropus giganteus). Ecohealth 2013, 10, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, J.H.; Anthony, S.J.; Islam, A.; Kilpatrick, A.M.; Ali Khan, S.; Balkey, M.D.; Ross, N.; Smith, I.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Tao, Y.; et al. Nipah Virus Dynamics in Bats and Implications for Spillover to Humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 17, 117, 29190–29201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.Z.; Islam, M.M.; Hossain, M.E.; Rahman, M.M.; Islam, A.; Siddika, A.; Hossain, M.S.S.; Sultana, S.; Islam, A.; Rahman, M.; et al. Genetic Diversity of Nipah Virus in Bangladesh. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 102, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, C.D.; Islam, A.; Rahman, M.Z.; Khan, S.U.; Rahman, M.; Satter, S.M.; Islam, A.; Yinda, C.K.; Epstein, J.H.; Daszak, P.; et al. Nipah Virus Detection at Bat Roosts after Spillover Events, Bangladesh, 2012–2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 1384–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, V.C.; Bhattacharyya, T.P. Report on a Collection of Mammals from Tripura. Rec. Zool. Surv. India 1977, 73, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Vogt, K.; Feeroz, M.M.; Hasan, M.K. A Re-discovery of Coelops frithii (Chiroptera, Hipposideridae) from Its Type Locality after One and A Half Century. Mammalia 2022, 86, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, C.C.; Kingston, T. Bats in the Anthropocene. In Bats in the Anthropocene: Conservation of Bats in a Changing World, 1st ed.; Voigt, C.C., Kingston, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, M.A.; Ali Reza, A.H.M.; Hasan, M.K.; Tonchangya, P.K.; Sarker, A.; Atiquzzaman, K.M.; Dutta, S.; Makayching; Rahman, K.M.Z. Some Noted on Three Species of Bats of Jahangirnagar University, Bangladesh. Zoos’ Print J. 2007, 22, 2729–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Rahman, F.; Aziz, M.A. Investigating the Least Known Small Mammals of Jahangirnagar University Campus, Bangladesh. Small Mammal. 2013, 5, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, A.; Hasan, M.K.; Feeroz, M.M. Indian Roundleaf Bat Hipposideros lankadiva: First Record for Bangladesh. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 2015, 112, 165–193. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, A.; Hasan, M.K.; Feeroz, M.M. The Confirmed Record of Pouched Tomb Bat (Saccolaimus saccolaimus) in Bangladesh with Notes on Morphometry. In The Festschrift on the 50th Anniversary of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; Ali, M.S., Feeroz, M.M., Naser, M.N., Eds.; IUCN Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, F.; Alam, S.M.I. Mating Behavior and Habitat Preference of Taphozous longimanus (Chiroptera) in Bangladesh. J. Biodivers. Bioprospect. Dev. 2018, 5, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painted Bat Found in Bangladesh After 133 Years. Available online: https://bangladeshpost.net/posts/painted-bat-found-in-bangladesh-after-133-years-63964 (accessed on 25 December 2021).

- Francis, C.M. A Comparison of Mist Nets and Two Designs of Harp Traps for Capturing Bats. J. Mammal. 1989, 70, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanshi, I.; Kingston, T. Introduction and Implementation of Harp Traps Signal a New Era in Bat Research. In 50 Years of Bat Research. Fascinating Life Sciences, 1st ed.; Lim, B.K., Fenton, M.B., Brigham, R.M., Mistry, S., Kurta, A., Gillam, E.H., Russell, A., Ortega, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 255–270. [Google Scholar]

- Tanshi, I.; Obitte, B.C.; Monadjem, A.; Kingston, T. Hidden Afrotropical Bat Diversity in Nigeria: Ten New Country Records from a Biodiversity Hotspot. Acta Chiropterol. 2021, 23, 313–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, T.; Francis, C.M.; Akbar, Z.; Kunz, T.H. Species Richness in an Insectivorous Bat Assemblage from Malaysia. J. Trop. Ecol. 2003, 19, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, T. Response of Bat Diversity to Forest Disturbance in Southeast Asia: Insights from Long-Term Research in Malaysia. In Bat Evolution, Ecology and Conservation, 1st ed.; Adams, R.A., Pedersen, S.C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; p. 547. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, T. Bats. In Core Standardized Methods for Rapid Biological Field Assessment; Larsen, T.H., Ed.; Conservation International: Arlington, VA, USA; pp. 59–82.

- Jones, G.; Van Parijs, S.M. 1993Bimodal Echolocation in Pipistrelle Bats: Are Cryptic Species Present? Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 1993, 251, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, T.; Lara, M.C.; Jones, G.; Schneider, C.J.; Akbar, Z.; Kunz, T.H. Acoustic Divergence in Two Cryptic Hipposideros Species: A Role for Social Selection? Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 2001, 268, 1381–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.L.; Britzke, E.R.; Handley, B.M.; Robbins, L.W. Surveying Bat Communities: A Comparison Between Mist Nets and The Anabat II Bat Detector System. Acta Chiropterol. 1999, 1, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- O’Farrell, M.J.; Gannon, W.L. A Comparison of Acoustic Versus Capture Techniques for The Inventory of Bats. J. Mammal. 1999, 80, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, D.; Armstrong, M.; Fisher, A.; Flores, A.; Pavey, C. A Comparison of Three Survey Methods for Collecting Bat Echolocation Calls and Species-Accumulation Rates from Nightly Anabat Recordings. Wildl. Res. 2004, 31, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wordley, C.F.R.; Sankaran, M.; Mudappa, D.; Altringham, J.D. Landscape Scale Habitat Suitability Modelling of Bats in the Western Ghats of India: Bats Like Something in Their Tea. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 191, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wordley, C.F.R.; Sankaran, M.; Mudappa, D.; Altringham, J.D. Bats in The Ghats: Agricultural Intensification Reduces Functional Diversity and Increases Trait Filtering in A Biodiversity Hotspot in India. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 210, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wordley, C.F.R.; Sankaran, M.; Mudappa, D.; Altringham, J.D. Heard but Not Seen: Comparing Bat Assemblages and Study Methods in A Mosaic Landscape in The Western Ghats of India. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 3883–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, J.T.; Monadjem, A.; Order, T.; McCleery, R.A. Response of Bat Activity to Land Cover and Land Use in Savannas is Scale-, Season-, and Guild-Specific. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görföl, T.; Huang, J.C.; Csorba, G.; Győrössy, D.; Estók, P.; Kingston, T.; Szabadi, K.L.; McArthur, E.; Senawi, J.; Furey, N.M.; et al. ChiroVox: A Public Library of Bat Calls. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemers, B.M. Bats in the Field and in A Flight Cage: Recordings and Analysis of Their Echolocation Calls and Behavior. In Bat Echolocation Research: Tools, Techniques and Analysis; Brigham, R.M., Kalko, E.K.V., Jones, G., Parsons, S., Limpens, H.J.G.A., Eds.; Bat Conservation International: Austin, TX, USA, 2004; pp. 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, E.E.; Silvis, A.; Brigham, R.M.; Czenze, Z.J. Bat Echolocation Research: A Handbook for Planning and Conducting Acoustic Studies, 2nd ed.; Bat Conservation International: Austin, TX, USA, 2020; p. 122. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, J.; Boller, M.; Erhardt, A.; Schwanghart, W. Spatial Bias in the GBIF Database and Its Effect on Modeling Species’ Geographic Distributions. Ecol. Inform. 2014, 19, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakes, E.H.; McGowan, P.J.; Fuller, R.A.; Chang-Qing, D.; Clark, N.E.; O’Connor, K.; Mace, G.M. Distorted Views of Biodiversity: Spatial and Temporal Bias in Species Occurrence Data. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher-Phelps, M.; Cao, G.; Wilson, R.M.; Kingston, T. Protecting Bias: Across Time and Ecology, Open-source Bat Locality Data Are Heavily Biased by Distance to Protected Area. Ecol. Inform. 2017, 40, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D.S.; Eick, G.N.; Schoeman, M.C.; Matthee, C.A. Cryptic Species in An Insectivorous Bat, Scotophilus dinganii. J. Mammal. 2006, 87, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ul Hasan, M.A.; Kingston, T. Bats of Bangladesh—A Systematic Review of the Diversity and Distribution with Recommendations for Future Research. Diversity 2022, 14, 1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14121042

Ul Hasan MA, Kingston T. Bats of Bangladesh—A Systematic Review of the Diversity and Distribution with Recommendations for Future Research. Diversity. 2022; 14(12):1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14121042

Chicago/Turabian StyleUl Hasan, Md Ashraf, and Tigga Kingston. 2022. "Bats of Bangladesh—A Systematic Review of the Diversity and Distribution with Recommendations for Future Research" Diversity 14, no. 12: 1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14121042

APA StyleUl Hasan, M. A., & Kingston, T. (2022). Bats of Bangladesh—A Systematic Review of the Diversity and Distribution with Recommendations for Future Research. Diversity, 14(12), 1042. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14121042