Exurbia East and West: Responses of Bird Communities to Low Density Residential Development in Two North American Regions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Locations

2.2. Bird Sampling

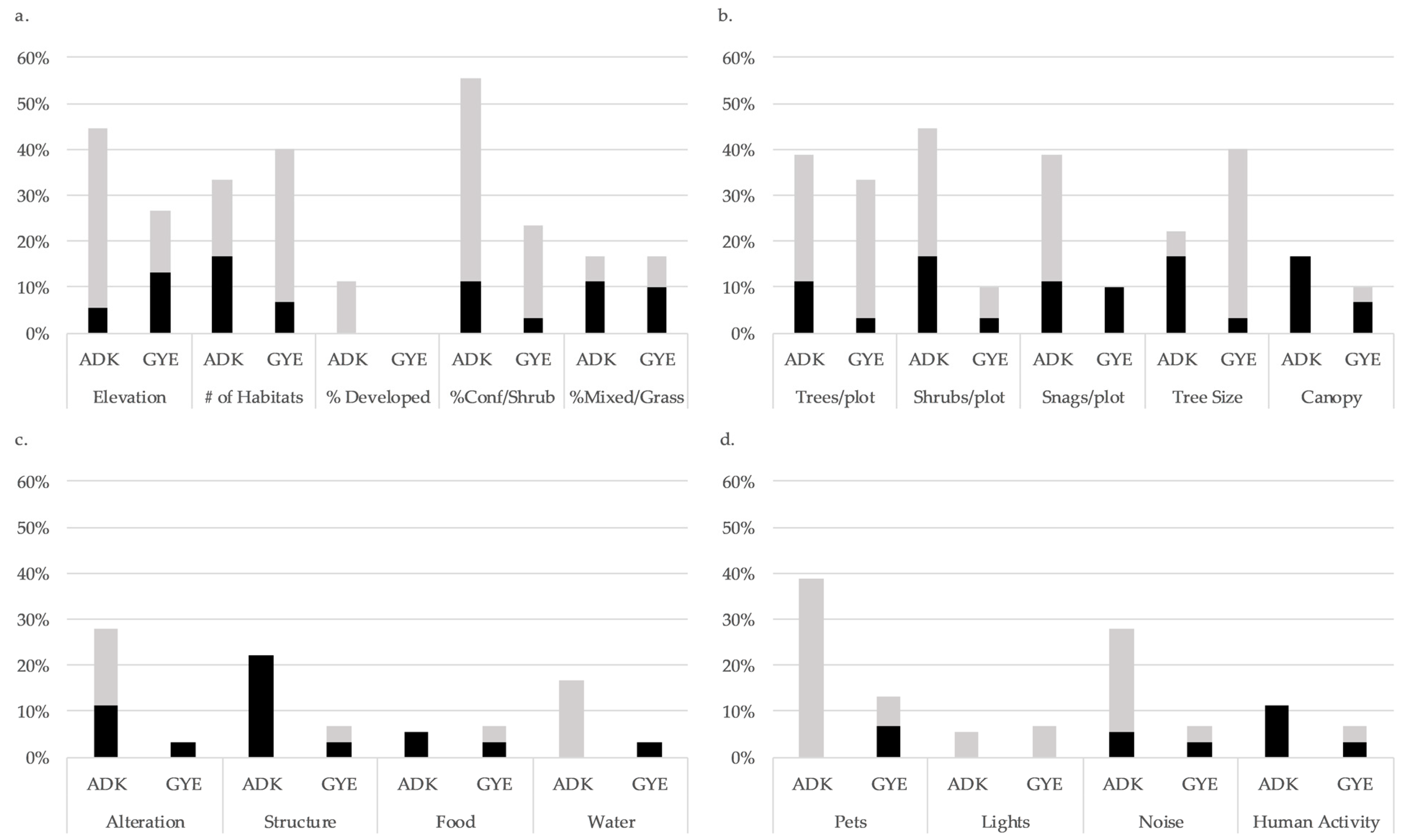

2.3. Habitat Context

2.4. Habitat Structure

2.5. Resource Provision/Alteration

2.6. Potential Disturbance

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cross-Site Comparison

3.2. Social Survey and Potential Disturbance

3.3. Habitat Use

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Covariate | Species | ß(SE) | Species | ß(SE) |

| Adirondack Park | Greater Yellowstone | |||

| Habitat Context | ||||

| Developed cover | AMGO | 1.81(2.20) | ||

| BLJA | 0.41 (0.58) | |||

| Conifer or Shrub cover | AMGO | 2.56 (3.20) | BRSP | 1.03 (0.36) |

| BHVI | 0.69 (0.74) | GTTO | 0.54 (0.31) | |

| BLBW | 1.62 (0.95) | MOBL | 1.51 (0.57) | |

| BLJA | 3.29 (4.08) | ROWR | 0.90 (0.37) | |

| DEJU | 0.63 (0.67) | SAVS | 0.69 (0.30) | |

| MAWA | 0.89 (0.27) | VESP | 1.83 (0.54) | |

| WIWR | 0.82 (0.51) | BHCO | −0.60 (0.46) | |

| WTSP | 1.18 (0.84) | |||

| BAWW | −0.90 (0.39) | |||

| YBSA | −0.92 (0.32) | |||

| Mixed or Grass cover | BLBW | 6.57 (4.49) | CORA | 6.48 (11.67) |

| CEDW | −0.68 (0.31) | WEME | 1.76 (0.67) | |

| DEJU | −0.48 (0.28) | GTTO | −0.33 (0.30) | |

| HOWR | −0.88 (0.29) | |||

| NOFL | −0.86 (0.34) | |||

| Elevation | AMGO | 0.71 (0.47) | HOWR | 0.98 (0.30) |

| BTBW | 1.20 (0.33) | NOFL | 1.29 (2.84) | |

| CEDW | 0.64 (0.43) | PISI | 2.75 (1.86) | |

| DEJU | 0.83 (0.48) | WCSP | 2.63 (0.65) | |

| HETH | 1.48 (0.59) | BBMA | −1.32 (0.45) | |

| MAWA | 1.37 (0.44) | GTTO | −0.15 (0.31) | |

| BLJA | −0.07 (0.39) | HOLA | −2.62 (0.63) | |

| RWBL | −0.92 (0.29) | |||

| Number of Habitats | BLBW | 1.31 (0.58) | BHCO | 0.81 (0.53) |

| BLJA | 0.94 (0.68) | DEJU | 1.83 (0.56) | |

| PIWO | 1.86 (1.77) | HOWR | 1.23 (0.43) | |

| BAWW | −0.64 (0.37) | PISI | 1.76 (0.59) | |

| CEDW | −0.54 (0.34) | RBNU | 4.42 (2.09) | |

| HAWO | −1.13 (0.46) | RCKI | 1.45 (0.37) | |

| WAVI | 1.78 (0.46) | |||

| WETA | 1.30 (0.47) | |||

| WEWP | 1.72 (0.74) | |||

| YEWA | 1.25 (0.39) | |||

| MOBL | −1.47 (0.49) | |||

| SAVS | −0.55 (0.28) | |||

| Habitat Structure | ||||

| Trees per plot | AMGO | 2.12 (1.50) | CLNU | 13.25 (9.25) |

| BHVI | 0.57 (0.69) | DEJU | 13.53 (5.48) | |

| BLJA | 0.37 (0.49) | DUFL | 14.51 (12.37) | |

| WIWR | 0.53 (0.33) | HOWR | 6.02 (3.65) | |

| WTSP | 0.72 (0.51) | MOCH | 566.42 (1.07) | |

| CEDW | −0.33 (0.26) | PISI | 15.28 (9.59) | |

| CHSP | −0.47 (0.25) | RCKI | 12.25 (4.61) | |

| WAVI | 15.69 (6.25) | |||

| YRWA | 22.98 (9.32) | |||

| SAVS | −0.61 (0.41) | |||

| Mean tree size | BLJA | 0.05 (0.39) | BHCO | 1.20 (0.84) |

| BAWW | −1.51 (2.23) | CHSP | 2.51 (2.39) | |

| BHVI | −0.35 (0.40) | CLNU | 1.64 (0.42) | |

| DEJU | −0.46 (0.30) | DUFL | 1.71 (0.53) | |

| HOWR | 1.38 (0.48) | |||

| MOCH | 3.19 (2.20) | |||

| NOFL | 1.48 (0.91) | |||

| PISI | 2.04 (0.99) | |||

| RCKI | 1.53 (0.38) | |||

| WAVI | 2.01 (0.62) | |||

| YRWA | 2.62 (1.03) | |||

| SAVS | −0.49 (0.27) | |||

| Shrubs per plot | AMCR | 1.54 (0.75) | BRSP | 2.08 (0.91) |

| AMGO | 1.04 (0.62) | GTTO | 0.61 (0.35) | |

| BLJA | 0.25 (0.43) | RWBL | −0.99 (0.40) | |

| CEDW | 0.61 (0.60) | |||

| DEJU | 0.83 (1.03) | |||

| BHVI | −0.73 (0.36) | |||

| BLBW | −0.84 (0.29) | |||

| PIWO | −0.99 (0.99) | |||

| Snags per plot | BHVI | 1.21 (1.12) | CORA | −1.01 (0.44) |

| BLBW | 1.72 (0.70) | GTTO | −0.32 (0.36) | |

| BLJA | 0.05 (0.39) | SAVS | −0.58 (0.39) | |

| WIWR | 0.92 (0.56) | |||

| WTSP | 1.06 (0.68) | |||

| BAWW | -1.04 (0.72) | |||

| CHSP | -1.07 (0.55) | |||

| Canopy cover | BLJA | −0.61 (0.43) | WETA | 292.41 (1.28) |

| CEDW | −0.50 (0.42) | CORA | −0.63 (0.41) | |

| DEJU | −0.94 (0.56) | SAVS | −0.58 (0.34) | |

| Resource Provision | ||||

| Structures | BHVI | −0.59 (0.50) | GTTO | 0.49 (0.31) |

| BLJA | −0.08 (0.39) | SAVS | −0.68 (0.31) | |

| DEJU | −0.70 (0.44) | |||

| Food | BLJA | −0.33 (0.37) | GTTO | 0.30 (0.26) |

| SAVS | −0.43 (0.28) | |||

| Water | BLJA | 0.53 (0.82) | GTTO | −0.53 (0.32) |

| DEJU | 0.36 (0.49) | |||

| RBNU | 0.85 (0.72) | |||

| Alteration | BLJA | 0.13 (0.38) | GTTO | −0.40 (0.29) |

| WIWR | 0.47 (0.27) | |||

| WTSP | 0.56 (0.33) | |||

| BHVI | −0.55 (0.72) | |||

| CEDW | −0.47 (0.34) | |||

| Disturbance | ||||

| Pets | AMCR | 0.81 (0.74) | BHCO | 0.15 (0.12) |

| AMGO | 0.81 (0.74) | GTTO | 0.16 (0.09) | |

| BLJA | 0.03 (0.17) | SAVS | −0.15 (0.09) | |

| MAWA | 0.42 (0.14) | WEME | −0.30 (0.10) | |

| RBNU | 0.30 (0.16) | |||

| WIWR | 0.18 (0.13) | |||

| WTSP | 0.26 (0.18) | |||

| Noise | AMCR | 0.28 (0.16) | BHCO | 0.19 (0.17) |

| AMGO | 0.28 (0.16) | GTTO | −0.11 (0.12) | |

| BLJA | 0.12 (0.15) | |||

| CEDW | 0.22 (0.19) | |||

| BHVI | −0.24 (0.37) | |||

| Lights | BLJA | 0.19 (0.16) | CORA | 0.42 (0.31) |

| SOSP | 3.52 (1.37) | |||

| Humans | BHVI | −0.12 (0.10) | BHCO | 0.17 (0.11) |

| BLJA | −0.03 (0.08) | MODO | −0.21 (0.08) | |

References

- Struyk, R.; Angelici, K. The Russian dacha phenomenon. Hous. Stud. 1996, 11, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.G.; Johnson, K.M.; Loveland, T.R.; Theobald, D.M. Rural land–use trends in the conterminous United States, 1950–2000. Ecol. Apps. 2005, 15, 1851–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odell, E.A.; Knight, R.L. Songbird and medium-sized mammal communities associated with exurban development in Pitkin County, Colorado. Conserv. Biol. 2001, 15, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odell, E.A.; Theobald, D.M.; Knight, R.L. Incorporating ecology into land use planning: The songbird’s case for clustered development. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 2003, 69, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.J.; Knight, R.; Marzluff, J.; Powell, S.; Brown, K.; Gude, P.; Jones, K. Effects of exurban development on biodiversity: Patterns, mechanisms, and research needs. Ecol. Apps. 2005, 15, 1893–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.K.; McChesney, R.; Munroe, D.K.; Irwin, E.G. Spatial characteristics of exurban settlement pattern in the United States. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 90, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.W.; O’Conner, R.J. Hierarchical correlates of bird assemblage structure on northeastern USA lakes. Environ. Monitor. Assess. 2000, 62, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cam, E.; Nichols, J.D.; Sauer, J.R.; Hines, J.E.; Flather, C.H. Relative species richness and community completeness: Birds and urbanization in the Mid-Atlantic states. Ecol. Apps. 2000, 10, 1196–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluza, D.A.; Griffin, C.R.; DeGraaf, R.M. Housing developments in rural New England: Effects on forest birds. Anim. Conserv. 2000, 3, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, R.B. Birds and butterflies along urban gradients in two ecoregions of the United States: Is urbanization creating a homogeneous fauna? In Biotic Homogenization: The Loss of Diversity through Invasion and Extinction; Lockwood, J.L., McKinney, M.L., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chace, J.F.; Walsh, J.J. Urban effects on native avifauna: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 74, 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimlich, R.E.; Anderson, W.D. Development at the Urban Fringe and Beyond: Impacts on Agriculture and Rural Land; Agricultural Economic Report No. 803; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2001.

- Barcus, H. Urban-rural migration in the USA: An analysis of residential satisfaction. Reg. Stud. 2004, 38, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeloff, V.C.; Stewart, S.I.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Gimmi, U.; Pidgeon, A.M.; Flather, C.H.; Hammer, R.B.; Helmers, D.P. Housing growth in and near United States protected areas limits their conservation value. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 940–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.M.; Davis, F.W.; McGhie, R.G.; Wright, R.G.; Groves, C.; Estes, J. Nature reserves: Do they capture the full range of America’s biological diversity? Ecol. Apps. 2001, 11, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glennon, M.J.; Curran, R.P. How much is enough? Distribution and protection status of habitats in the Adirondacks. Adirondack J. Environ. Stud. 2013, 19, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.S.; Nelson, A.C. The new “burbs”. The exurbs and their implications for planning policy. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 1994, 60, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairncross, F. The Death of Distance; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, A.J.; Rasker, R.; Maxwell, B.; Rotella, J.J.; Johnson, J.D.; Parmenter, A.W.; Langner, U.; Cohen, W.B.; Lawrence, R.L.; Kraska, M.P.V. Ecological causes and consequences of demographic change in the new west. Bioscience 2002, 52, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilty, J.A.; Merenlender, A.M. Studying biodiversity on private lands. Cons. Biol. 2003, 17, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.A.; Marvin, S.J.; Fortmann, L.P. Landscape changes in Nevada County reflect social and ecological transitions. Calif. Agric. 2003, 57, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.E. Nature, affordability, and privacy as motivations for exurban living. Urban Geogr. 2008, 29, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretser, H.E.; Hilty, J.; Glennon, M.; Burrell, J.; Smith, Z.; Knuth, B.A. Challenges of governance and land management on the exurban/wilderness frontier in the USA. In Beyond the Urban-rural Divide; Andersson, K., Eklund, E., Lehtola, M., Salmi, P., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing, Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, R.F.; Trombulak, S.C.; Baldwin, E.D. Assessing risk of large–scale habitat conversion in lightly settled landscapes. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2009, 91, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcove, D.; Bean, M.; Bonnie, R.; McMillan, M. Rebuilding the Arc: Toward a More Effective Endangered Species Act for Private Land; Environmental Defense Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.R.; Hobbs, R.J. Conservation where people live and work. Conserv. Biol. 2002, 16, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinerstein, E.; Vynne, C.; Sala, E.; Joshi, A.R.; Fernando, S.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Mayorga, J.; Olson, D.; Asner, G.P.; Baillie, J.E.M.; et al. A global deal for nature: Guiding principles, milestones, and targets. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaw2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Res. 372. A Resolution Expressing the Sense of the Senate that the Federal Government Should Establish a National Goal of Conserving at Least 30 Percent of the Land and Ocean of the United States by 2030. 116th Congress. Available online: https://congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-resolution/372/ (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- H. Res. 835. A Resolution Expressing the Sense of the House of Representatives that the Federal Government Should Establish a National Goal of Conserving at Least 30 Percent of the Land and Ocean of the United States by 2030. 116th Congress. Available online: https://congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-resolution/835/ (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Maestas, J.D.; Knight, R.L.; Gilgert, W.C. Biodiversity and land use change in the American mountain west. Geogr. Rev. 2001, 91, 509–524. [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, J.P.; Berger, J. Rapid ecological and behavioral changes in carnivores: The response of black bears (Ursus americanus) to altered food. J. Zool. 2003, 261, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, D. Beast in the Garden; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J.C.; Klemens, M.W. Primary and secondary effects of habitat alteration. In Turtle Conservation; Klemens, M.W., Ed.; Smithsonsian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pidgeon, A.M.; Radeloff, V.C.; Flather, C.H.; Lepczyk, C.A.; Clayton, M.K.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Hammer, R.B. Associations of forest bird species richness with housing and landscape patterns across the USA. Ecol. Appl. 2007, 17, 1989–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraterrigo, J.M.; Wiens, J.A. Bird communities of the Colorado Rocky Mountains along a gradient of exurban development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 71, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glennon, M.J.; Porter, W.F. Effects of land use management on biotic integrity: An investigation of bird communities. Biol. Cons. 2005, 126, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, R.T.T. Land Mosaics: The Ecology of Landscapes and Regions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Benton, T.; Vickery, J.A.; Wilson, J.D. Farmland biodiversity: Is habitat heterogeneity the key? Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003, 18, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dover, J.; Settele, J. The influences of landscape structure on butterfly distribution and movement: A review. J. Insect Conserv. 2009, 13, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoto, M.; Heikkinen, R.K. Disregarding topographical heterogeneity biases species turnover assessments based in bioclimate models. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2008, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindvall, O. Habitat heterogeneity and survival in a bush cricket metapopulation. Ecology 1996, 77, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piha, H.; Luoto, M.; Piha, M.; Merilä, J. Anuran abundance and persistence in agricultural landscapes during a climatic extreme. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2007, 13, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, T.; Roy, D.B.; Hill, J.K.; Brereton, T.; Thomas, C.D. Heterogeneous landscapes promote population stability. Ecol. Lett. 2010, 13, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, T.L.; Dobkin, D.S. Introduction: Habitat fragmentation and western birds. In Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Birds in Western Landscapes: Contrasts with Paradigms from the Eastern United States, Studies in Avian Biology No. 25; George, T.L., Dobkin, D.S., Eds.; Cooper Ornithological Society, Allen Press, Inc: Lawrence, KS, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Glennon, M.J.; Kretser, H.E.; Hilty, J.A. Identifying common patterns in diverse systems: Effects of exurban development on birds of the Adirondack Park and the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, USA. Environ. Manag. 2014, 55, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glennon, M.J.; Kretser, H.E. Size of the ecological effect zone associated with exurban development in the Adirondack Park, N.Y. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 112, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, D.M.; Miller, J.R.; Hobbs, N.T. Estimating the cumulative effects of development on wildlife habitat. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1997, 39, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, M.D.; Manley, P.N.; Holyoak, M. Distinguishing stressors acting on land bird communities in an urbanizing environment. Ecology 2008, 89, 2302–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gude, P.H.; Hansen, A.J.; Rasker, R.; Maxwell, B. Rates and drivers of rural residential development in the Greater Yellowstone. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 77, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, E.G.; Geoghegan, J. Theory, data, methods: Developing spatially explicit economic models of land use change. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2001, 85, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, G.C.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Sanchez–Azofeifa, G.A. Countryside biogeography: Use of human-dominated habitats by the avifauna of southern Costa Rica. Ecol. Apps. 2001, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricketts, T.H.; Daily, G.C.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Fay, J.P. Countryside biogeography of moths in a fragmented landscape: Biodiversity in native and agricultural habitats. Conserv. Biol. 2001, 15, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner-Devine, M.C.; Daily, G.C.; Ehrlich, P.R. Countryside biogeography of tropical butterflies. Cons. Biol. 2003, 17, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, A. A Sand County Almanac: And Sketches Here and There; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.G.; Clark, M.; Ferree, C.E.; Jospe, A.; Olivero Sheldon, A.; Weaver, K.J. Northeast Habitat Guides: A Companion to the Terrestrial and Aquatic Habitat Maps; The Nature Conservancy, Eastern Conservation Science, Eastern Regional Office: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.conservationgateway.org/ConservationByGeography/NorthAmerica/UnitedStates/edc/reportsdata/hg/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- LANDFIRE Remap 2016 Existing Vegetation Type (EVT) CONUS. U.S. Geological Survey. Available online: https://www.landfire.gov/evt.php (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- Theobald, D.M. Placing exurban land-use change in a human modification framework. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2004, 2, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New York State Constitution; Article XIV; Section 1; State of New York: New York, NY, USA, 1938.

- Ralph, C.G.; Droege, S.; Sauer, J.R. Managing and monitoring birds using point counts: Standards and applications. In Monitoring Bird Populations by Point Counts; Sauer, J.R., Droege, S., Eds.; Technical Report PSW-GTR-149; United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service: Albany, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, T.E.; Paine, C.R.; Conway, C.J.; Hochachka, W.M.; Jenkins, W. BBIRD Field Protocol; Montana Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit, University of Montana: Missoula, MT, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smith, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Mail, and Mixed–mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rinehart, K.A.; Donovan, T.M.; Mitchell, B.R.; Long, R.A. Factors influencing occupancy patterns of Eastern newts across Vermont. J. Herpetol. 2009, 43, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWan, A.A.; Sullivan, P.J.; Lembo, A.J.; Smith, C.R.; Maerz, J.C.; Lassoie, J.P.; Richmond, M.E. Using occupancy models of forest breeding birds to prioritize conservation planning. Biol. Cons. 2009, 142, 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, G.; Nichols, J.D.; Hines, J.E.; Stouffer, P.C.; Bierregaard, R.O., Jr.; Lovejoy, T.E. A large–scale deforestation experiment: Effects of patch area and isolation on Amazon birds. Science 2007, 315, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, J.A. PRESENCE2–Software to Estimate Patch Occupancy and Related Parameters; United States Geological Survey Patuxent Wildlife Research Center: Denver, CO, USA, 2006. Available online: https://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/software/presence.html (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- MacKenzie, D.I. Modeling the probability of resource use: The effect of, and dealing with, detecting a species imperfectly. J. Wildl. Manag. 2006, 70, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, D.I.; Nichols, J.D.; Royle, J.A.; Pollock, K.H.; Bailey, L.L.; Hines, J.E. Occupancy Estimation and Modeling: Inferring Patterns and Dynamics of Species Occurrence; Elsevier: Burlington, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chesser, R.T.; Billerman, S.M.; Burns, K.J.; Cicero, C.; Dunn, J.L.; Kratter, A.W.; Lovette, I.J.; Mason, N.A.; Rasmussen, P.C.; Remsen, J.V., Jr.; et al. Sixty–first supplement to the American Ornithological Society’s checklist of North American birds. Auk 2020, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, K.P.; Anderson, D.R.; Huyvaert, K.P. AIC model selection and multimodel inference in behavioral ecology: Some background, observations, and comparisons. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2011, 65, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, C.M.; Pejchar, L.; Reed, S.E. Subdivision design and stewardship affect bird and mammal use of conservation developments. Ecol. Apps. 2017, 27, 1236–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, C.E.; Bock, J.H. Biodiversity and residential development beyond the urban fringe. In The Planner’s Guide to Natural Resource Conservation: The Science of Land Development Beyond the Metropolitan Fringe; Esparza, A.X., McPherson, G., Eds.; Springer Nature: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, C.E.; Jones, Z.F.; Bock, J.H. The oasis effect: Response of birds to exurban development in a southwestern savanna. Ecol. Apps. 2008, 18, 1093–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morelli, T.L.; Smith, A.B.; Kastely, C.R.; Mastroserio, I.; Moritz, C.; Beissinger, S.R. Anthropogenic refugia ameliorate the severe climate-related decline of a montane mammal along its trailing edge. Proc. R. Soc. B 2012, 279, 4279–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhning–Gaese, K. Determinants of avian species richness at different spatial scales. J. Biogeogr. 2007, 24, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groffman, P.M.; Cavender–Bares, J.; Bettez, N.D.; Grove, J.M.; Hall, S.J.; Heffernan, J.B.; Hobbie, S.E.; Larson, K.L.; Morse, J.L.; Neill, C.; et al. Ecological homogenization of urban USA. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 12, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glennon, M.J.; Kretser, H.E. State of the birds in exurbia. Adirondack J. Environ. Stud. 2016, 20, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, K.V.; Dokter, A.M.; Blancher, P.J.; Sauer, J.R.; Smith, A.C.; Smith, P.A.; Stanton, J.C.; Panjabi, A.; Helft, L.; Parr, M.; et al. Decline of the North American Avifauna. Science 2019, 366, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avian Conservation Assessment Database. Partners in Flight c2019. Available online: http://pif.birdconservancy.org/files/US_Canada%20Regional%20ACAD%206–03–20.xlsx (accessed on 21 November 2020).

- Bollinger, E.K.; Peak, R.G. Depredation of artificial avian nests: A comparison of forest–field and forest–lake edges. Am. Midl. Nat. 1995, 143, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heske, E.J.; Robinson, S.K.; Brawn, J.D. Predator activity and predation on songbird nests on forest–field edges in east–central Illinois. Landsc. Ecol. 1999, 14, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goad, E.H.; Pejchar, L.; Reed, S.E.; Knight, R.L. Habitat use by mammals varies along an exurban development gradient in northern Colorado. Biol. Cons. 2014, 176, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, V.; Fuller, T.K.; Sauvajot, R.M. Activity and distribution of gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) in southern California. Southwest. Nat. 2012, 57, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita, R.; Mira, A.; Moreira, F.; Morgado, R.; Beja, P. Influence of landscape characteristics on carnivore density and abundance in Mediterranean farmland. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2009, 132, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glennon, M.J.; Porter, W.F. Impacts of land use management on small mammals in the Adirondack Park, New York. Northeast. Nat. 2007, 14, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpass, J.S.; Rodewald, A.D.; Matthews, S.N. Species-dependent effects of bird feeders on nest predators and nest survival of urban American robins and northern cardinals. Condor 2017, 119, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, C.E.; Bock, J.H. Abundance and variety of birds associated with point sources of water in southwestern New Mexico, USA. J. Arid Environ. 2015, 116, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulé, M.E.; Bolger, D.T.; Alberts, A.C.; Wright, J.; Sorice, M.; Hill, S. Reconstructed dynamics of rapid extinctions of chaparral-requiring birds in urban habitat islands. Conserv. Biol. 1988, 2, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, E.G.; Dickman, C.R.; Letnic, M.; Vanak, A.T. Dogs as predators and trophic regulators. In Free-Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation; Gompper, M.E., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, P.B.; Bryant, J.V. Four–legged friend or foe? Dog walking displaces native birds from natural areas. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 611–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Length, B.E.; Knight, R.L.; Brennan, M.E. The effects of dogs on wildlife communities. Nat. Areas J. 2008, 28, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, C.; Longcore, T. (Eds.) Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.W. Apparent effects of light pollution on singing behavior of American robins. Condor 2006, 108, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, J.R.; Crooks, K.J.; Fristrup, K.M. The costs of chronic noise exposure for terrestrial organisms. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 25, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, J.; Nakagawa, S.; Cleasby, I.R.; Burke, T. Passerine birds breeding under chronic noise experience reduced fitness. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijnen, R.; Foppen, R.; Terbraak, C.; Thissen, J. The effects of car traffic on breeding bird populations in woodland. 3. Reduction of density in relation to proximity of the main roads. J. Appl. Ecol. 1995, 32, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, C.D.; Ortega, C.P.; Cruz, A. Noise pollution changes avian communities and species interactions. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 1415–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, C.D.; Ortega, C.P.; Kennedy, R.I.; Nylander, P.J. Are nest predators absent from noisy areas or unable to locate nests? Ornithol. Monogr. 2012, 74, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kight, C.R.; Hinders, M.K.; Swaddle, J.P. Acoustic space is affected by anthropogenic habitat features: Implications for avian vocal communication. Ornithol. Monogr. 2012, 74, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Golding, S.A.; Winkler, R.L. Tracking urbanization and exurbs: Migration across the rural-urban continuum, 1990–2016. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2020, 39, 835–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C.J. Coronavirus Escape: To the Suburbs. New York Times. 8 May 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/08/realestate/coronavirus–escape–city–to–suburbs.html (accessed on 23 November 2020).

- Hostetler, M. Beyond design: The importance of construction and post–construction phases in green developments. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1128–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostetler, M. The Green Leap: A Primer for Conserving Biodiversity in Subdivision Development; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler, M.; Drake, D. Conservation subdivisions: A wildlife perspective. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 90, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.E.; Hilty, J.A.; Theobald, D.M. Guidelines and incentives for conservation development in local land-use regulations. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretser, H.E.; Dale, E.; Karasin, L.; Reed, S.E.; Goldstein, L.J. Factors influencing adoption and implementation of conservation development ordinances in the rural United States. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 9, 1021–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, S.H.; Turner, V.K.; Bang, C. Homeowner associations as a vehicle for promoting native urban biodiveristy. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Structures | Habitat Alteration |

|---|---|

| House | Lawn |

| Barn | Pasture |

| Shed | Logging/Forestry |

| Closed garage | Landscaping |

| Other outbuilding | Rock |

| Fence | |

| Powerline | Transportation |

| Satellite dish | Primary road |

| Picnic table | Secondary road |

| Outdoor seating | Dirt road |

| Playset | Recreational trail/use |

| Target (shooting) | Vehicle(s) |

| Deck/Gazebo | Motorcycle |

| Firepit | ATV |

| Birdhouse(s) | Snowmobile |

| Golf cart | |

| Food Sources | |

| Flower garden(s) | Disturbance |

| Vegetable garden(s) | Cat |

| Fruiting shrubs/trees | Dog |

| Bird feeder | Cattle |

| Grill | Horses |

| Compost | Other livestock |

| Pet food | Outdoor lights |

| Open garbage | Evidence of outdoor lights on at night |

| Lawnmower | |

| Water sources | Snowblower |

| Bird bath | Chainsaw |

| Pool | Power tools |

| Water trough | Active construction |

| Stock tank | Kid toys |

| Hot tub | |

| Other water sources |

| Model |

|---|

| ψ (.), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (trees per plot), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (shrubs per plot), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (snags per plot), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (mean tree size), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (canopy cover), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (developed cover), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (conifer cover 1), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (mixed forest cover 1), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (number of habitats), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (mean elevation), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (structure), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (alteration), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (food), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (water), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (pets), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (noise), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (lights), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| ψ (humans), p (date, time, temperature, wind, sky, observer) |

| Common Name | Scientific Name | AOU | Ψs | SE | Ψc | SE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adirondack Park | ||||||

| American crow | Corvus brachyrhynchos | AMCR | 0.90 | 0.04 | 0.72 | 0.05 |

| American goldfinch | Spinus tristis | AMGO | 0.79 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.07 |

| Black-and-white warbler | Mniotilta varia | BAWW | 0.60 | 0.06 | 0.60 | 0.06 |

| Blue-headed vireo | Vireo solitaries | BHVI | 0.95 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.04 |

| Blackburnian warbler | Setophaga fusca | BLBW | 0.79 | 0.04 | 0.81 | 0.04 |

| Blue jay | Cyanocitta cristata | BLJA | 0.91 | 0.03 | 0.93 | 0.03 |

| Black-thr. blue warbler | Setophaga caerulescens | BTBW | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.05 |

| Cedar waxwing | Bombycilla cedrorum | CEDW | 0.84 | 0.08 | 0.68 | 0.09 |

| Chipping sparrow | Spizella passerina | CHSP | 0.65 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| Dark-eyed junco | Junco hyemalis | DEJU | 0.80 | 0.07 | 0.55 | 0.07 |

| Hairy woodpecker | Dryobates villosus | HAWO | 0.85 | 0.14 | 0.85 | 0.13 |

| Hermit thrush | Catharus guttatus | HETH | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.94 | 0.03 |

| Magnolia warbler | Setophaga magnolia | MAWA | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.05 |

| Pileated woodpecker | Dryocopus pileatus | PIWO | 0.88 | 0.12 | 0.84 | 0.11 |

| Red-breasted nuthatch | Sitta canadensis | RBNU | 0.69 | 0.06 | 0.89 | 0.05 |

| Winter wren | Troglodytes hiemalis | WIWR | 0.54 | 0.05 | 0.84 | 0.04 |

| White-throated sparrow | Zonotrichia albicollis | WTSP | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.38 | 0.05 |

| Yellow-bell. sapsucker | Sphyrapicus varius | YBSA | 0.67 | 0.06 | 0.80 | 0.06 |

| Greater Yellowstone | ||||||

| Black-billed magpie | Pica hudsonia | BBMA | 0.66 | 0.06 | 0.43 | 0.06 |

| Brown-headed cowbird | Molothrus ater | BHCO | 0.88 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.04 |

| Brewer’s sparrow | Spizella breweri | BRSP | 0.81 | 0.04 | 0.81 | 0.04 |

| Chipping sparrow | Spizella passerina | CHSP | 0.82 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 0.04 |

| Clark’s nutcracker | Nucifraga columbiana | CLNU | 0.44 | 0.10 | 0.59 | 0.11 |

| Common raven | Corvus corax | CORA | 0.95 | 0.04 | 0.96 | 0.04 |

| Dark-eyed junco | Junco hyemalis | DEJU | 0.52 | 0.05 | 0.55 | 0.05 |

| Dusky flycatcher | Empidonax oberholseri | DUFL | 0.59 | 0.06 | 0.60 | 0.06 |

| Green-tailed towhee | Pipilo chlorurus | GTTO | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 0.05 |

| Horned lark | Eremophila alpestris | HOLA | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.35 | 0.06 |

| House wren | Troglodytes aedon | HOWR | 0.67 | 0.06 | 0.54 | 0.07 |

| Mountain bluebird | Sialia currucoides | MOBL | 0.88 | 0.04 | 0.57 | 0.06 |

| Mountain chickadee | Poecile gambeli | MOCH | 0.69 | 0.05 | 0.69 | 0.05 |

| Mourning dove | Zenaida macroura | MODO | 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 0.07 |

| Northern flicker | Colaptes auratus | NOFL | 0.72 | 0.05 | 0.68 | 0.06 |

| Pine siskin | Spinus pinus | PISI | 0.79 | 0.04 | 0.77 | 0.05 |

| Red-breasted nuthatch | Sitta canadensis | RBNU | 0.41 | 0.07 | 0.49 | 0.07 |

| Ruby-crowned kinglet | Regulus calendula | RCKI | 0.52 | 0.05 | 0.53 | 0.05 |

| Rock wren | Salpinctes obsoletus | ROWR | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.07 |

| Red-winged blackbird | Agelaius phoeniceus | RWBL | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.04 |

| Savannah sparrow | Passerculus sandwichensis | SAVS | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.51 | 0.05 |

| Song sparrow | Melospiza melodia | SOSP | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.06 |

| Vesper’s sparrow | Pooecetes gramineus | VESP | 0.84 | 0.04 | 0.66 | 0.06 |

| Warbling vireo | Vireo gilvus | WAVI | 0.61 | 0.05 | 0.65 | 0.05 |

| White-crowned sparrow | Zonotrichia leucophrys | WCSP | 0.59 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 0.06 |

| Western meadowlark | Sturnella neglecta | WEME | 0.76 | 0.06 | 0.65 | 0.06 |

| Western tanager | Piranga ludoviciana | WETA | 0.62 | 0.10 | 0.73 | 0.11 |

| Western wood-pewee | Contopus sordidulus | WWPE | 0.56 | 0.07 | 0.51 | 0.07 |

| Yellow warbler | Setophaga petechia | YEWA | 0.54 | 0.05 | 0.52 | 0.05 |

| Yellow-rumped warbler | Setophaga coronata | YRWA | 0.67 | 0.04 | 0.67 | 0.04 |

| Pets 1 | ADK (n = 114) | GYE (n = 97) |

|---|---|---|

| Horses live on my land | 2.5% | 16.5% |

| Chickens live on my land | 1.6% | 8.2% |

| Cats live on my land | 9.8% | 24.7% |

| Dogs live on my land | 41% | 67% |

| A dog went outside during the day | 2.88 | 3.74 |

| A dog went outside during the night | 2.48 | 2.83 |

| A dog chased or killed wildlife | 1.15 | 1.30 |

| A cat went outside during the day | 1.25 | 1.87 |

| A cat went outside during the night | 1.15 | 1.74 |

| A cat chased or killed wildlife | 1.13 | 1.27 |

| Noise 1 | ADK (n = 117) | GYE (n = 9 7) |

| Mowed the lawn with a gas or electric lawnmower | 2.54 | 2.62 |

| Listened to music outside my house | 1.87 | 2.01 |

| Worked on a small construction project around my house (painting, installing new windows, etc.) | 2.46 | 2.82 |

| Used power tools (e.g., chainsaw, leaf blower) | 2.51 | 2.40 |

| Worked on large construction project around my house (room addition, constructed outbuilding, etc.) | 21% | 26% |

| Human Activity on Property 1 | ADK (n = 117) | GYE (n = 97) |

| Used a grill outside | 2.79 | 3.11 |

| Ate meals outside my house (e.g., on a porch, by a fire pit, etc.) | 2.97 | 3.02 |

| Had kids playing in my yard | 2.27 | 2.59 |

| Engaged in non-motorized winter recreation on my property | 2.41 | 1.86 |

| Walked dogs on my property | 2.71 | 3.27 |

| Hiked trails | 2.98 | 3.01 |

| Mountain biked | 1.47 | 1.53 |

| Went horseback riding | 1.04 | 1.73 |

| Went off-roading (i.e., with an ATV, dirt bike, snowmobile) | 1.15 | 1.77 |

| Used a trail camera or wildlife camera | 24% | 15% |

| Went birdwatching | 57% | 60% |

| Lights 2 | ADK (n = 119) | GYE (n = 97) |

| About how many outdoor lights do you have affixed to various places outside of your house or other buildings on your property? | 4.67 | 4.03 |

| At what times do you have these (outdoor) lights on? | ||

| Evenings (after sundown) | 73.8% | 55.7% |

| Overnight | 2.5% | 4.1% |

| Mornings (before sunrise) | 3.3% | 6.2% |

| How frequently are these outdoor lights on? | 9% | 10.3% |

| About how many indoor lights do you have on at night that shine through your windows without curtains? | 5.10 | 3.05 |

| At what times do you have these (indoor) lights on? | ||

| Evenings (after sundown) | 82% | 79.4% |

| Overnight | 4.1% | 4.1% |

| Mornings (before sunrise) | 11.5% | 6.2% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Glennon, M.J.; Kretser, H.E. Exurbia East and West: Responses of Bird Communities to Low Density Residential Development in Two North American Regions. Diversity 2021, 13, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13020042

Glennon MJ, Kretser HE. Exurbia East and West: Responses of Bird Communities to Low Density Residential Development in Two North American Regions. Diversity. 2021; 13(2):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13020042

Chicago/Turabian StyleGlennon, Michale J., and Heidi E. Kretser. 2021. "Exurbia East and West: Responses of Bird Communities to Low Density Residential Development in Two North American Regions" Diversity 13, no. 2: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13020042

APA StyleGlennon, M. J., & Kretser, H. E. (2021). Exurbia East and West: Responses of Bird Communities to Low Density Residential Development in Two North American Regions. Diversity, 13(2), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13020042