A Hydrolase-Rich Venom Beyond Neurotoxins: Integrative Functional Proteomic and Immunoreactivity Analyses Reveal Novel Peptides in the Amazonian Scorpion Brotheas amazonicus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

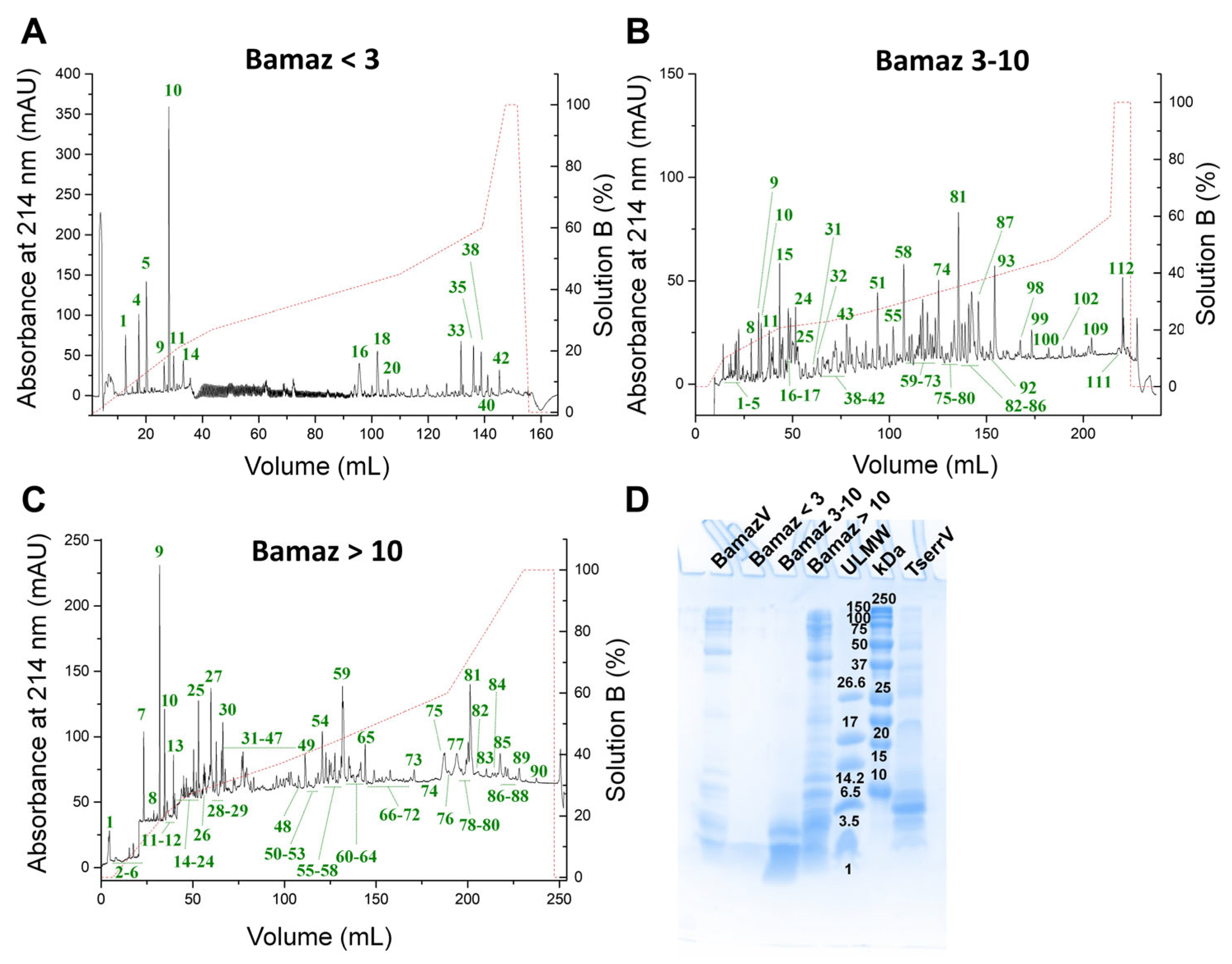

2.1. Molecular Fractionation Reveals Compositional Complexity

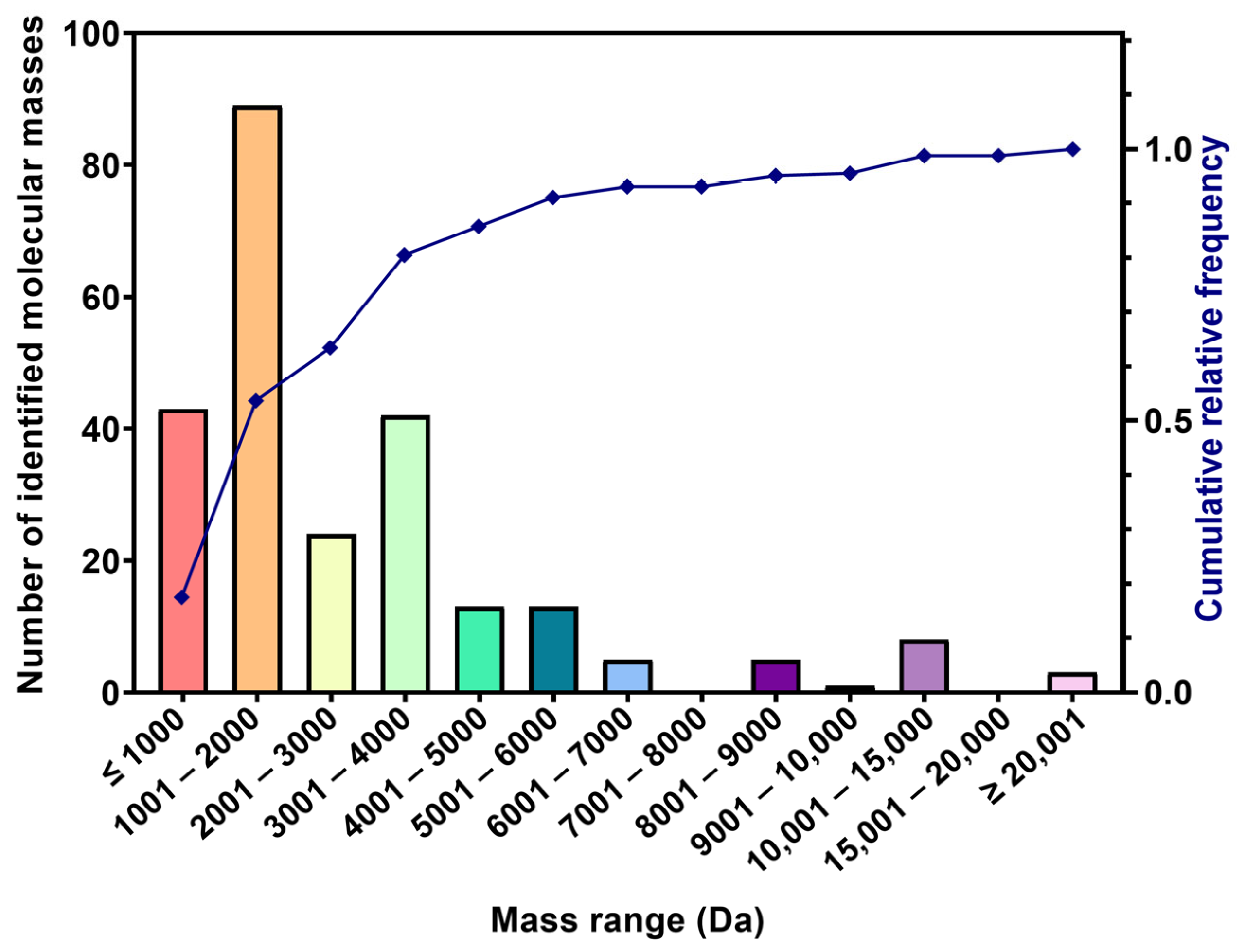

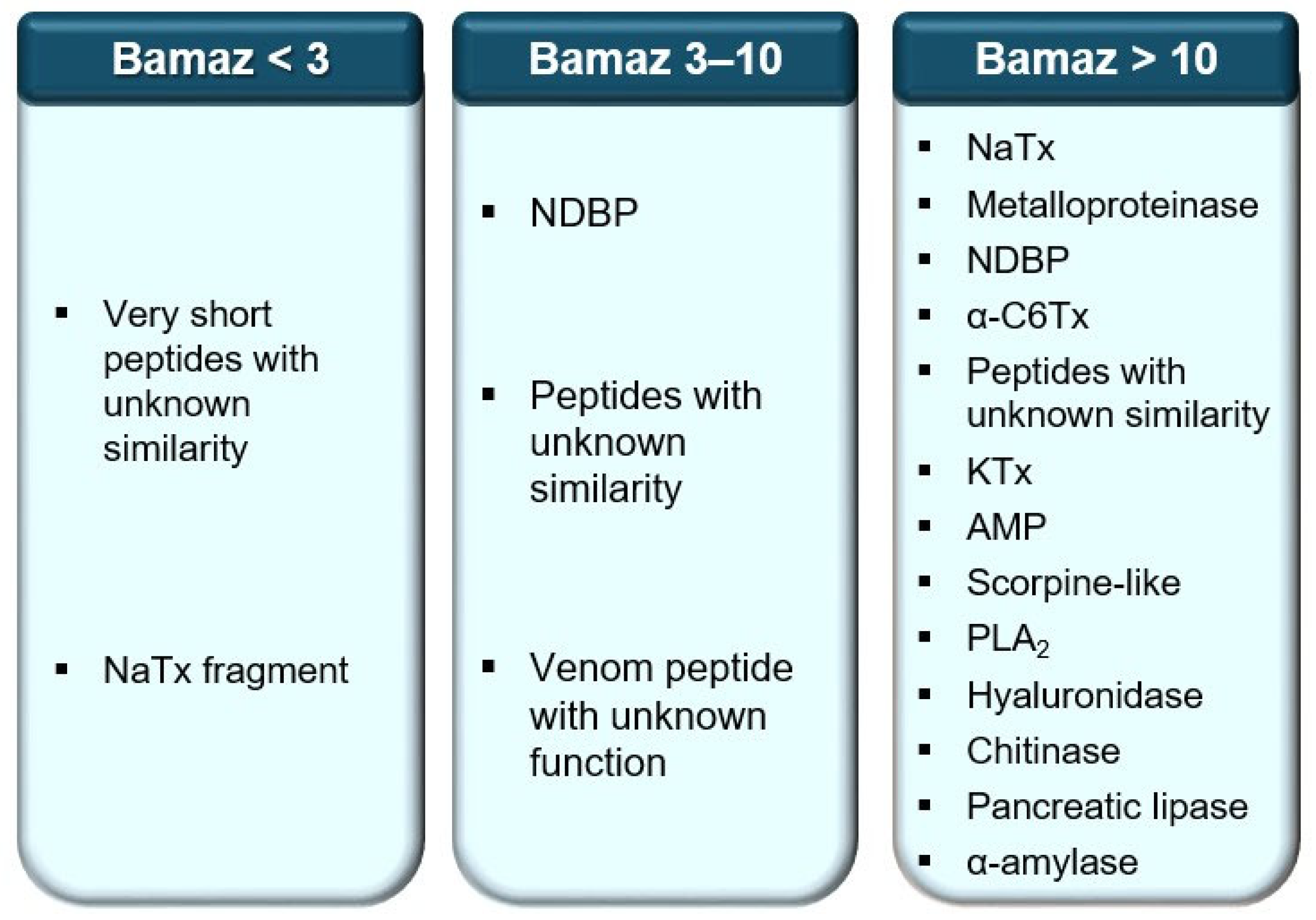

2.2. Proteomic Identification Unveils Novel Peptides

2.2.1. Predominance of Low-Molecular-Mass Peptides

2.2.2. Novelty and Database Coverage

2.2.3. Evidence for Proteolytic Processing and Post-Translational Modifications

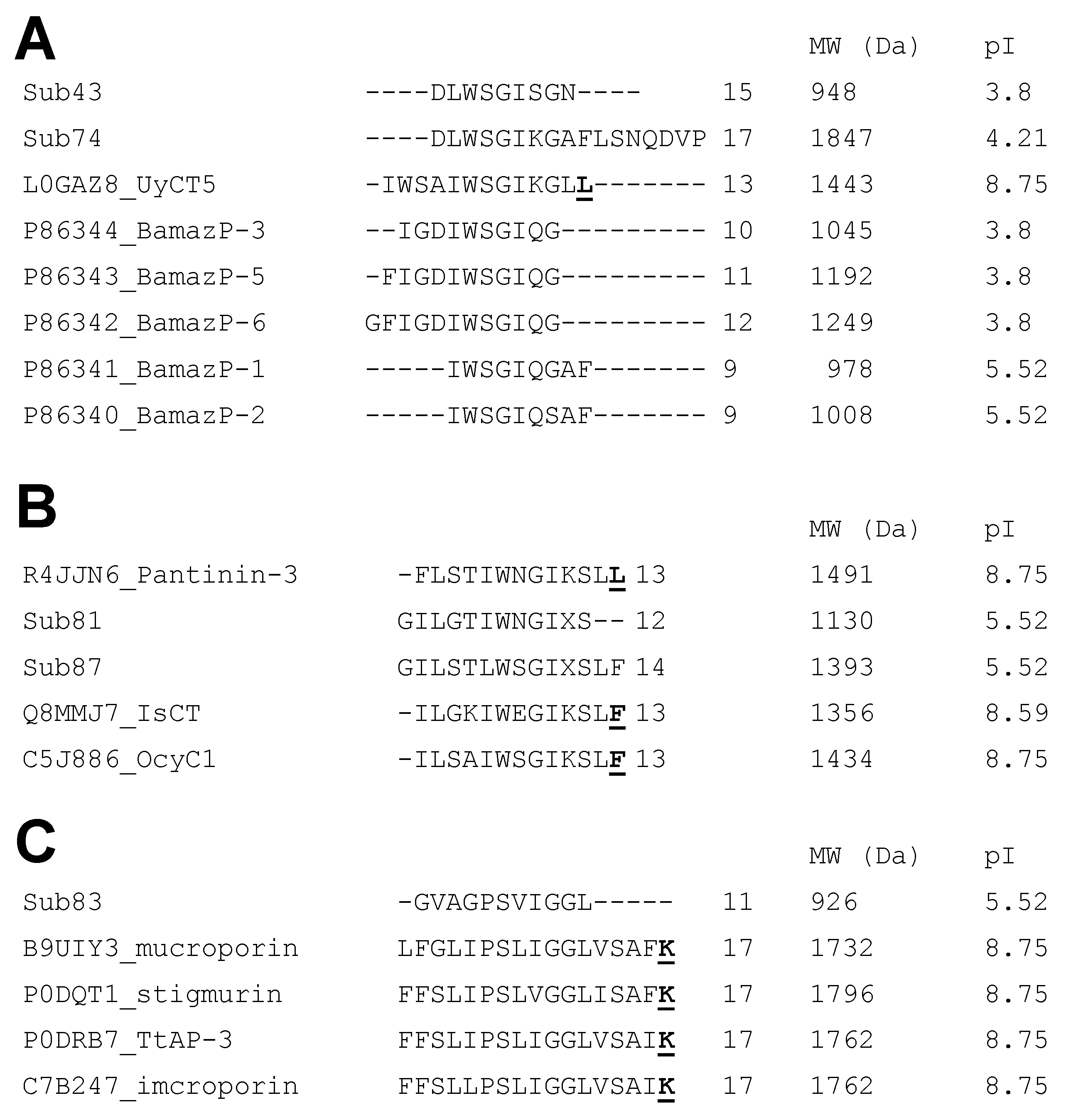

2.2.4. Putative Functional Classes

2.3. Post-Translational Diversity and Evolutionary Convergence Buthid Toxins

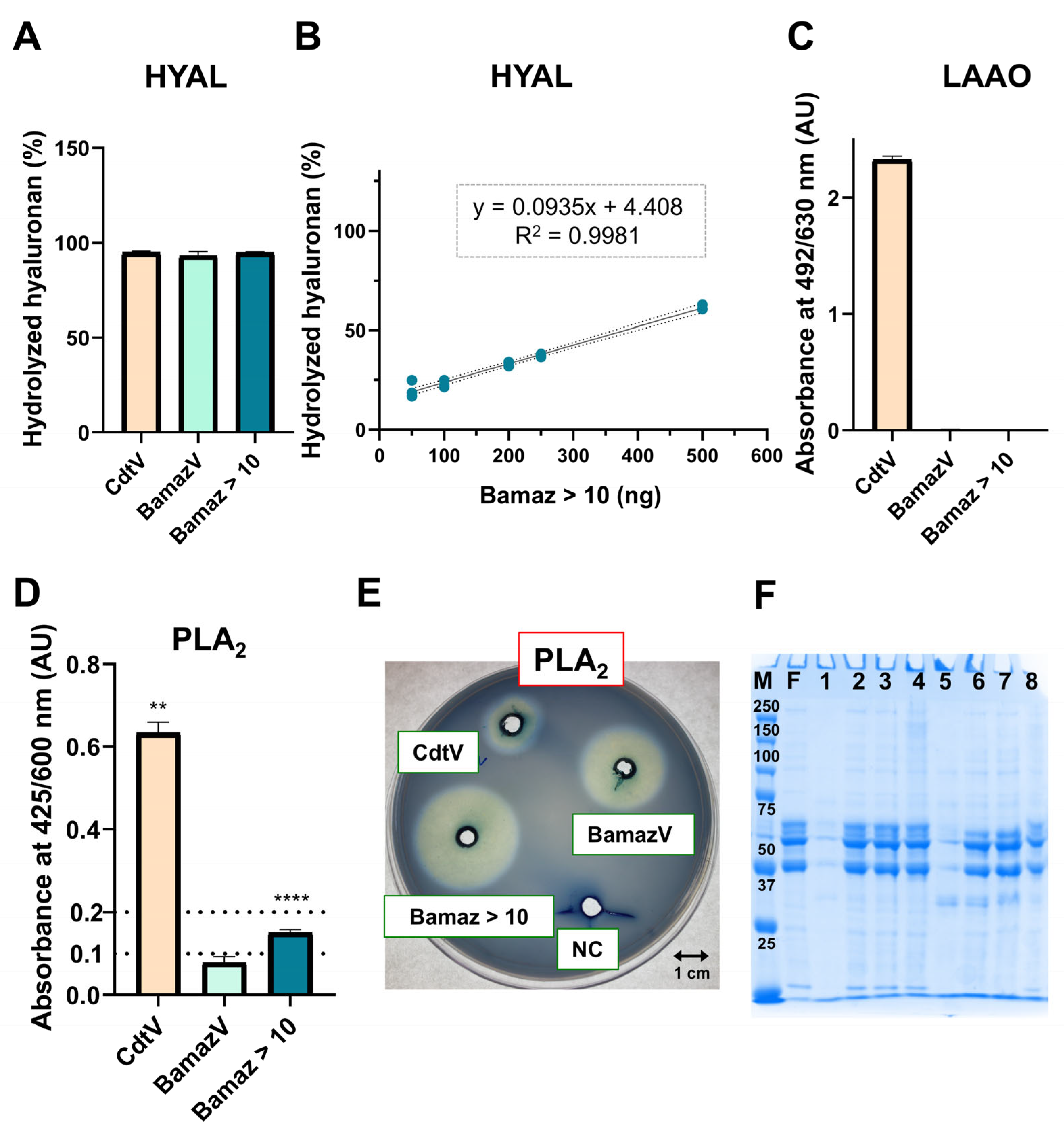

2.4. Enzymatic Repertoire Highlights Potential Spreading and Inflammatory Roles

2.4.1. Spreading Enzymes

2.4.2. Inflammatory/Cytolytic Enzymes

2.4.3. Absent or Reduced Enzymes (Oxidases/Proteases)

2.4.4. Ecological and Functional Interpretation

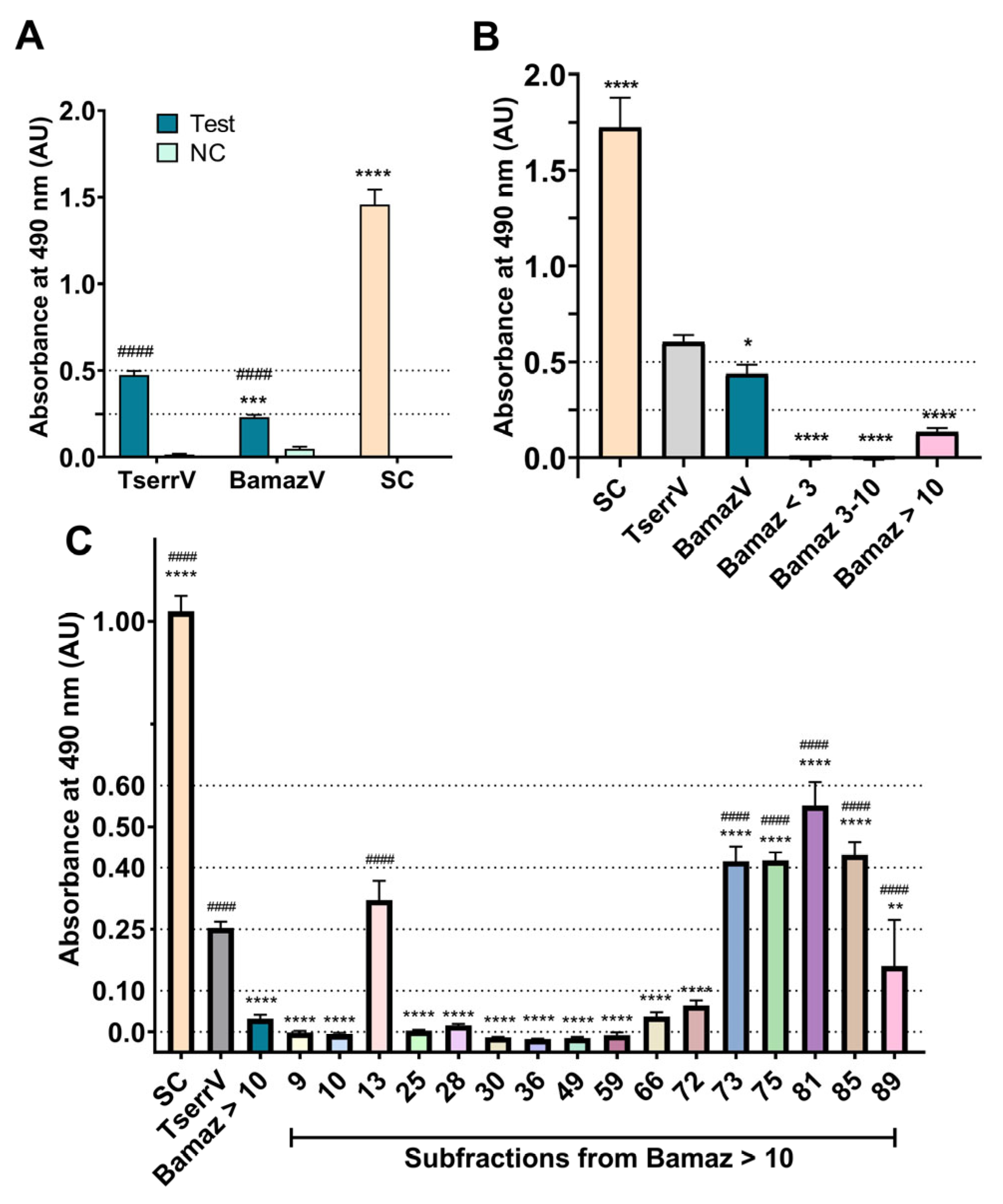

2.5. Limited Cross-Recognition of B. amazonicus Venom and Its Fractions by Commercial Scorpion Antivenom

2.6. Antivenom Recognition Correlates with Enzyme-Rich Subfractions

2.7. Integrative Interpretation: B. amazonicus Venom as an Enzyme-Dominant, Reduced-Neurotoxic Proteome

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Venom and Its Fractions

3.2. Tris-Tricine SDS-PAGE

3.3. B. amazonicus Venom Fractionation by Reversed-Phase Chromatography

3.4. Identification of B. amazonicus Venom Components

3.4.1. Mass Spectrometry

3.4.2. N-Terminal Sequencing

3.5. Evaluation of the Enzymatic Activity of BamazV and Bamaz > 10

3.5.1. Sample Preparation

3.5.2. PLA2 Enzymatic Activity

3.5.3. L-Amino Acid Oxidase Activity

3.5.4. Hyaluronidase Activity

3.5.5. Fibrinogenolytic Activity

3.6. Evaluation of the Recognition of BamazV and Its Fractions and Subfractions by CommercialScorpion Antivenom

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ac | N-terminal acetylation |

| ALC | Average local confidence |

| Am | Amidation |

| Amm | Ammonia loss |

| AMP | Antimicrobial peptide |

| BamazV | Brotheas amazonicus venom |

| Bamaz < 3 | Brotheas amazonicus venom fraction with components shorter than 3 kDa |

| Bamaz 3–10 | Brotheas amazonicus venom fraction with components between 3 and 10 kDa |

| Bamaz > 10 | Brotheas amazonicus venom fraction with components higher than 10 kDa |

| CdtV | Crotalus durissus terrificus venom |

| CTAB | Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide |

| D | Dehydration |

| EDTA | Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| F | Bovine fibrinogen |

| HCCA | α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid |

| KTx | potassium channel toxins |

| LAAO | L-amino acid oxidase |

| M | Molecular weight marker |

| MALDI | Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization |

| MIC | Minimal inhibitory concentration |

| MPBS | Phosphate-buffered saline with milk |

| MW | Molecular weight |

| NaTx | Sodium channel toxins |

| NC | Negative control |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| NDBP | Non-disulfide bridge peptide |

| NOB | 4-nitro-3-(octanoyloxy)benzoic acid |

| OPD | o-phenylenediamine |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| pI | Isoeletric point |

| PLA2 | Phospholipase A2 |

| PMSF | Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride |

| PTM | Post-translational modification |

| SA | Sinapinic acid |

| SC | Secondary antibody control |

| SDS-PAGE | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis |

| SISBIO | Brazilian Biodiversity Information and Authorization System |

| SISGEN | National System for Management of Genetic Heritage and Associated Traditional Knowledge |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

| TOF | Time-of-flight |

| TRU | Turbidity reducing units |

| TserrV | Tityus serrulatus venom |

| ULMW | Ultra-low molecular weight marker |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Evans, E.R.J.; Northfield, T.D.; Daly, N.L. Venom costs and optimization in scorpions. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintero-Hernández, V.; Jiménez-Vargas, J.M.; Gurrola, G.B.; Valdivia, H.H.; Possani, L.D. Scorpion venom components that affect ion-channels function. Toxicon 2013, 76, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Prudencio, G.; Cid-Uribe, J.I.; Morales, J.A.; Possani, L.D.; Ortiz, E.; Romero-Gutiérrez, T. The Enzymatic Core of Scorpion Venoms. Toxins 2022, 14, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiezel, G.A.; Oliveira, I.S.; Reis, M.B.; Ferreira, I.G.; Cordeiro, K.R.; Bordon, K.C.F.; Arantes, E.C. The complex repertoire of Tityus spp. venoms: Advances on their composition and pharmacological potential of their toxins. Biochimie 2024, 220, 144–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, S.; Borges, A.; Sahyoun, C.; Nasr, R.; Roufayel, R.; Legros, C.; Sabatier, J.M.; Fajloun, Z. Scorpion Venom as a Source of Antimicrobial Peptides: Overview of Biomolecule Separation, Analysis and Characterization Methods. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.G.; Santos, G.C.; Procópio, R.E.L.; Arantes, E.C.; Bordon, K.C.F. Scorpion species of medical importance in the Brazilian Amazon: A review to identify knowledge gaps. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 27, e20210012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.; Graham, M.R.; Cândido, D.M.; Pardal, P.P.O. Amazonian scorpions and scorpionism: Integrating toxinological, clinical, and phylogenetic data to combat a human health crisis in the world’s most diverse rainfores. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 27, e20210028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Duarte, C.; Saavedra-Langer, R.; Matavel, A.; Oliveira-Mendes, B.B.R.; Chavez-Olortegui, C.; Paiva, A.L.B. Scorpion envenomation in Brazil: Current scenario and perspectives for containing an increasing health problem. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanan da Cruz, J.; Bulet, P.; Mendonça de Moraes, C. Exploring the potential of Brazilian Amazonian scorpion venoms: A comprehensive review of research from 2001 to 2021. Toxicon X 2024, 21, 100182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, A.K.; Caricati, C.P.; Lima, M.L.; Dos Santos, M.C.; Kipnis, T.L.; Eickstedt, V.R.; Knysak, I.; Da Silva, M.H.; Higashi, H.G.; Da Silva, W.D. Antigenic cross-reactivity among the venoms from several species of Brazilian scorpions. Toxicon 1994, 32, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.B.; Martins, J.G.; Bordon, K.C.F.; de Campos Fraga-Silva, T.F.; de Lima Procópio, R.E.; de Almeida, B.R.R.; Bonato, V.L.D.; Arantes, E.C. Pioneering in vitro characterization of macrophage response induced by scorpion venoms from the Brazilian Amazon. Toxicon 2023, 230, 107171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, D.B.; Martins, J.G.; Oliveira, M.S.; Lima-Júnior, R.S.; Rocha, L.C.; Andrade, S.L.; Procópio, R.E.L. Leishmanicidal activity of the venoms of the Scorpions Brotheas amazonicus and Tityus metuendus. Braz. J. Biol. 2023, 83, e276872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höfer, H.; Wollscheid, E.; Gasnier, T.R.J. The relative abundance of Brotheas amazonicus (Chactidae, Scorpiones) in different habitat types of a central Amazon rainforest. J. Arachnol. 1996, 24, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Higa, A.; Noronha, M.d.D.; López-Lozano, J.L. Degradation of Aa and Bb chains from bovine fibrinogen by serine proteases of the Amazonian scorpion Brotheas amazonicus. BMC Proc. 2014, 8, P12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.F.; Carvalho, L.S.; Carvalho, M.A.; Schneider, M.C. Chromosome diversity in Buthidae and Chactidae scorpions from Brazilian fauna: Diploid number and distribution of repetitive DNA sequences. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2023, 46, e20220083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, B.; Malcher, S.; Costa, M.; Martins, J.; Procópio, R.; Noronha, R.; Nagamachi, C.; Pieczarka, J. High Chromosomal Reorganization and Presence of Microchromosomes in Chactidae Scorpions from the Brazilian Amazon. Biology 2023, 12, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, G.; Borges, A. A checklist of the scorpions of Ecuador (Arachnida: Scorpiones), with notes on the distribution and medical significance of some species. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 21, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.B.; De Castro Figueiredo Bordon, K.; Martins, J.G.; Wiezel, G.A.; Cipriano, U.G.; Emerson de Lima Procópio, R.; Deperon Bonato, V.L.; Arantes, E.C. A novel scorpine-like peptide from the amazonian scorpion Brotheas amazonicus with cytolytic activity. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1652614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordon, K.C.F.; Santos, G.C.; Martins, J.G.; Wiezel, G.A.; Amorim, F.G.; Crasset, T.; Redureau, D.; Quinton, L.; Procópio, R.E.L.; Arantes, E.C. Pioneering Comparative Proteomic and Enzymatic Profiling of Amazonian Scorpion Venoms Enables the Isolation of Their First α-Ktx, Metalloprotease, and Phospholipase A2. Toxins 2025, 17, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verano-Braga, T.; Dutra, A.A.; León, I.R.; Melo-Braga, M.N.; Roepstorff, P.; Pimenta, A.M.; Kjeldsen, F. Moving pieces in a venomic puzzle: Unveiling post-translationally modified toxins from Tityus serrulatus. J. Proteome Res. 2013, 12, 3460–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, A.M.; Stöcklin, R.; Favreau, P.; Bougis, P.E.; Martin-Eauclaire, M.F. Moving pieces in a proteomic puzzle: Mass fingerprinting of toxic fractions from the venom of Tityus serrulatus (Scorpiones, Buthidae). Rapid Commun. Mass. Spectrom. 2001, 15, 1562–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, C.V.F.; Roman-Gonzalez, S.A.; Salas-Castillo, S.P.; Zamudio, F.Z.; Gomez-Lagunas, F.; Possani, L.D. Proteomic analysis of the venom from the scorpion Tityus stigmurus: Biochemical and physiological comparison with other Tityus species. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C-Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2007, 146, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, U.C.; Candido, D.M.; Dorce, V.A.; Junqueira-de-Azevedo, I.e.L. The transcriptome recipe for the venom cocktail of Tityus bahiensis scorpion. Toxicon 2015, 95, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beraldo-Neto, E.; Vigerelli, H.; Coelho, G.R.; da Silva, D.L.; Nencioni, A.L.A.; Pimenta, D.C. Unraveling and profiling Tityus bahiensis venom: Biochemical analyses of the major toxins. J. Proteom. 2023, 274, 104824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, U.C.; Nishiyama, M.Y.; Dos Santos, M.B.V.; Santos-da-Silva, A.P.; Chalkidis, H.M.; Souza-Imberg, A.; Candido, D.M.; Yamanouye, N.; Dorce, V.A.C.; Junqueira-de-Azevedo, I.L.M. Proteomic endorsed transcriptomic profiles of venom glands from Tityus obscurus and T. serrulatus scorpions. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalapothakis, Y.; Miranda, K.; Pereira, A.H.; Witt, A.S.A.; Marani, C.; Martins, A.P.; Leal, H.G.; Campos-Júnior, E.; Pimenta, A.M.C.; Borges, A.; et al. Novel components of Tityus serrulatus venom: A transcriptomic approach. Toxicon 2021, 189, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomonte, B.; Calvete, J.J. Strategies in ‘snake venomics’ aiming at an integrative view of compositional, functional, and immunological characteristics of venoms. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 23, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S. Proteome and peptidome profiling of spider venoms. Expert. Rev. Proteom. 2008, 5, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rates, B.; Ferraz, K.K.; Borges, M.H.; Richardson, M.; De Lima, M.E.; Pimenta, A.M. Tityus serrulatus venom peptidomics: Assessing venom peptide diversity. Toxicon 2008, 52, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalapothakis, Y.; Miranda, K.; Molina, D.A.M.; Conceição, I.M.C.A.; Larangote, D.; Op den Camp, H.J.M.; Kalapothakis, E.; Chávez-Olórtegui, C.; Borges, A. An overview of Tityus cisandinus scorpion venom: Transcriptome and mass fingerprinting reveal conserved toxin homologs across the Amazon region and novel lipolytic components. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 225, 1246–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireno, I.C.; Rates, B.A.; Pimenta, A.M.C. Brazilian scorpion Brotheas amazonicus venom peptidomics. UniProtKB. 2009. Available online: https://www.uniprot.org/citations/CI-D1ICQ9T2GOU31 (accessed on 20 January 2026).

- Delgado-Prudencio, G.; Becerril, B.; Possani, L.D.; Ortiz, E. New proposal for the systematic nomenclature of scorpion peptides. Toxicon 2025, 253, 108192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cologna, C.T.; Rodrigues, R.S.; Santos, J.; de Pauw, E.; Arantes, E.C.; Quinton, L. Peptidomic investigation of Neoponera villosa venom by high-resolution mass spectrometry: Seasonal and nesting habitat variations. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 24, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdez-Cruz, N.A.; Batista, C.V.; Possani, L.D. Phaiodactylipin, a glycosylated heterodimeric phospholipase A2 from the venom of the scorpion Anuroctonus phaiodactylus. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004, 271, 1453–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cologna, C.T.; Peigneur, S.; Rosa, J.C.; Selistre-de-Araujo, H.S.; Varanda, W.A.; Tytgat, J.; Arantes, E.C. Purification and characterization of Ts15, the first member of a new alpha-KTX subfamily from the venom of the Brazilian scorpion Tityus serrulatus. Toxicon 2011, 58, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Ramírez, K.; Quintero-Hernández, V.; Vargas-Jaimes, L.; Batista, C.V.; Winkel, K.D.; Possani, L.D. Characterization of the venom from the Australian scorpion Urodacus yaschenkoi: Molecular mass analysis of components, cDNA sequences and peptides with antimicrobial activity. Toxicon 2013, 63, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santibáñez-López, C.E.; Aharon, S.; Ballesteros, J.A.; Gainett, G.; Baker, C.M.; González-Santillán, E.; Harvey, M.S.; Hassan, M.K.; Abu Almaaty, A.H.; Aldeyarbi, S.M.; et al. Phylogenomics of Scorpions Reveal Contemporaneous Diversification of Scorpion Mammalian Predators and Mammal-Active Sodium Channel Toxins. Syst. Biol. 2022, 71, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunagar, K.; Undheim, E.A.; Chan, A.H.; Koludarov, I.; Muñoz-Gómez, S.A.; Antunes, A.; Fry, B.G. Evolution stings: The origin and diversification of scorpion toxin peptide scaffolds. Toxins 2013, 5, 2456–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, D.; Bonilla, E.; Vega, C. Scorpion venom and its adaptive role against pathogens: A case study in Centruroides granosus Thorell, 1876 and Escherichia coli. Front. Arachn. Sci. 2023, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiming, Z.; Yibao, M.; Yawen, H.; Zhiyong, D.; Yingliang, W.; Zhijian, C.; Wenxin, L. Comparative venom gland transcriptome analysis of the scorpion Lychas mucronatus reveals intraspecific toxic gene diversity and new venomous components. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goméz-Mendoza, D.P.; Lemos, R.P.; Jesus, I.C.G.; Gorshkov, V.; McKinnie, S.M.K.; Vederas, J.C.; Kjeldsen, F.; Guatimosim, S.; Santos, R.A.; Pimenta, A.M.C.; et al. Moving Pieces in a Cellular Puzzle: A Cryptic Peptide from the Scorpion Toxin Ts14 Activates AKT and ERK Signaling and Decreases Cardiac Myocyte Contractility via Dephosphorylation of Phospholamban. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 3467–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo-Braga, M.N.; Moreira, R.D.S.; Gervásio, J.H.D.B.; Felicori, L.F. Overview of protein posttranslational modifications in Arthropoda venoms. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 28, e20210047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerni, F.A.; Pucca, M.B.; Amorim, F.G.; Bordon, K.D.F.; Echterbille, J.; Quinton, L.; De Pauw, E.; Peigneur, S.; Tytgat, J.; Arantes, E.C. Isolation and characterization of Ts19 Fragment II, a new long-chain potassium channel toxin from Tityus serrulatus venom. Peptides 2016, 80, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Eauclaire, M.; Céard, B.; Ribeiro, A.; Diniz, C.; Rochat, H.; Bougis, P. Biochemical, pharmacological and genomic characterisation of Ts IV, an α-toxin from the venom of the South American scorpion Tityus serrulatus. FEBS Lett. 1994, 342, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.; Zeng, X.C.; Zeng, X.; Nie, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S.; Bao, A. Transcriptomic analysis of the venom glands from the scorpion Hadogenes troglodytes revealed unique and extremely high diversity of the venom peptides. J. Proteom. 2017, 150, 40–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Lei, Y.; Qin, H.; Cao, Z.; Kwok, H.F. Deciphering Scorpion Toxin-Induced Pain: Molecular Mechanisms and Ion Channel Dynamics. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2025, 21, 2921–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L.C.; Viana, G.M.M.; Nencioni, A.L.A.; Pimenta, D.C.; Beraldo-Neto, E. Scorpion Peptides and Ion Channels: An Insightful Review of Mechanisms and Drug Development. Toxins 2023, 15, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, R.; Zamudio, F.Z.; Rodríguez, M.H.; Possani, L.D. Scorpine, an anti-malaria and anti-bacterial agent purified from scorpion venom. FEBS Lett. 2000, 471, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Giraldo, E.; Carrillo, E.; Titaux-Delgado, G.; Cano-Sánchez, P.; Colorado, A.; Possani, L.D.; Río-Portilla, F.D. Structural and functional studies of scorpine: A channel blocker and cytolytic peptide. Toxicon 2023, 222, 106985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuzita, F.J.; Pinkse, M.W.; Patane, J.S.; Juliano, M.A.; Verhaert, P.D.; Lopes, A.R. Biochemical, transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of digestion in the scorpion Tityus serrulatus: Insights into function and evolution of digestion in an ancient arthropod. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.H.; Bjourson, A.J.; Orr, D.F.; Shaw, C.; McClean, S. Amphibian skin secretomics: Application of parallel quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry and peptide precursor cDNA cloning to rapidly characterize the skin secretory peptidome of Phyllomedusa hypochondrialis azurea: Discovery of a novel peptide family, the hyposins. J. Proteome Res. 2007, 6, 3604–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim-Carmo, B.; Parente, A.M.S.; Souza, E.S.; Silva-Junior, A.A.; Araújo, R.M.; Fernandes-Pedrosa, M.F. Antimicrobial Peptide Analogs From Scorpions: Modifications and Structure-Activity. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 887763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, V.A.; Cremonez, C.M.; Anjolette, F.A.; Aguiar, J.F.; Varanda, W.A.; Arantes, E.C. Functional and structural study comparing the C-terminal amidated β-neurotoxin Ts1 with its isoform Ts1-G isolated from Tityus serrulatus venom. Toxicon 2014, 83, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinnar, A.E.; Butler, K.L.; Park, H.J. Cathelicidin family of antimicrobial peptides: Proteolytic processing and protease resistance. Bioorg Chem. 2003, 31, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.M.; Di, L. Strategies to optimize peptide stability and prolong half-life. In Peptide Therapeutics: Fundamentals of Design, Development, and Delivery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 163–182. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Prudencio, G.; Possani, L.D.; Becerril, B.; Ortiz, E. The Dual α-Amidation System in Scorpion Venom Glands. Toxins 2019, 11, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, R.J.; Serem, J.C.; Oosthuizen, C.B.; Semenya, D.; Serian, M.; Lorenz, C.D.; Mason, A.J.; Bester, M.J.; Gaspar, A.R.M. Carboxy-Amidated AamAP1-Lys has Superior Conformational Flexibility and Accelerated Killing of Gram-Negative Bacteria. Biochemistry 2025, 64, 841–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Gómez, S.; Vargas-Muñoz, L.J.; Saldarriaga-Córdoba, M.M.; van der Meijden, A. MS/MS analysis of four scorpion venoms from Colombia: A descriptive approach. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 27, e20200173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Mendes, B.B.R.; Miranda, S.E.M.; Sales-Medina, D.F.; Magalhães, B.F.; Kalapothakis, Y.; Souza, R.P.; Cardoso, V.N.; de Barros, A.L.B.; Guerra-Duarte, C.; Kalapothakis, E.; et al. Inhibition of Tityus serrulatus venom hyaluronidase affects venom biodistribution. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu, C.B.; Bordon, K.C.F.; Cerni, F.A.; Oliveira, I.S.; Balenzuela, C.; Alexandre-Silva, G.M.; Zoccal, K.F.; Reis, M.B.; Wiezel, G.A.; Peigneur, S.; et al. Pioneering study on Rhopalurus crassicauda scorpion venom: Isolation and characterization of the major toxin and hyaluronidase. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, A.C.M.; de Santana, C.J.C.; Melani, R.D.; Domont, G.B.; Castro, M.S.; Fontes, W.; Roepstorff, P.; Júnior, O.R.P. Exploring the biological activities and proteome of Brazilian scorpion Rhopalurus agamemnon venom. J. Proteom. 2021, 237, 104119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, C.; Rivera, J.; Lomonte, B.; Bonilla, F.; Diego-García, E.; Camacho, E.; Tytgat, J.; Sasa, M. Venom characterization of the bark scorpion Centruroides edwardsii (Gervais 1843): Composition, biochemical activities and in vivo toxicity for potential prey. Toxicon 2019, 171, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ravelo, R.; Coronas, F.I.; Zamudio, F.Z.; González-Morales, L.; López, G.E.; Urquiola, A.R.; Possani, L.D. The Cuban scorpion Rhopalurus junceus (Scorpiones, Buthidae): Component variations in venom samples collected in different geographical areas. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 19, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedian, R.; Pipelzadeh, M.H.; Jalali, A.; Kim, E.; Lee, H.; Kang, C.; Cha, M.; Sohn, E.T.; Jung, E.S.; Rahmani, A.H.; et al. Enzymatic analysis of Hemiscorpius lepturus scorpion venom using zymography and venom-specific antivenin. Toxicon 2010, 56, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costal-Oliveira, F.; Duarte, C.G.; Machado de Avila, R.A.; Melo, M.M.; Bordon, K.C.F.; Arantes, E.C.; Paredes, N.C.; Tintaya, B.; Bonilla, C.; Bonilla, R.E.; et al. General biochemical and immunological characteristics of the venom from Peruvian scorpion Hadruroides lunatus. Toxicon 2012, 60, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Tobar, L.L.; Clement, H.; Arenas, I.; Sepulveda-Arias, J.C.; Vargas, J.A.G.; Corzo, G. An overview of some enzymes from buthid scorpion venoms from Colombia: Centruroides margaritatus, Tityus pachyurus, and Tityus n. sp. aff. metuendus. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2024, 30, e20230063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venancio, E.J.; Portaro, F.C.; Kuniyoshi, A.K.; Carvalho, D.C.; Pidde-Queiroz, G.; Tambourgi, D.V. Enzymatic properties of venoms from Brazilian scorpions of Tityus genus and the neutralisation potential of therapeutical antivenoms. Toxicon 2013, 69, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, R.B.; Kurup, P.A. Investigations on the venom of the South Indian scorpion Heterometrus scaber. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1975, 381, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutti, R.; Tamascia, M.L.; Hyslop, S.; Rocha-E-Silva, T.A. Purification and characterization of a hyaluronidase from venom of the spider Vitalius dubius (Araneae, Theraphosidae). J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas-Ruiz, D.E.; Gonzalez-Kozlova, E.E.; Delgadillo, J.; Palermo, P.M.; Sandoval, G.A.; Lazo, F.; Rodríguez, E.; Chávez-Olórtegui, C.; Yarlequé, A.; Sanchez, E.F. Biochemical and molecular characterization of the hyaluronidase from Bothrops atrox Peruvian snake venom. Biochimie 2019, 162, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessini, A.C.; Takao, T.T.; Cavalheiro, E.C.; Vichnewski, W.; Sampaio, S.V.; Giglio, J.R.; Arantes, E.C. A hyaluronidase from Tityus serrulatus scorpion venom: Isolation, characterization and inhibition by flavonoids. Toxicon 2001, 39, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Gao, R.; Gopalakrishnakone, P. Isolation and characterization of a hyaluronidase from the venom of Chinese red scorpion Buthus martensi. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C-Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008, 148, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morey, S.S.; Kiran, K.M.; Gadag, J.R. Purification and properties of hyraluronidase from Palamneus gravimanus (Indian black scorpion) venom. Toxicon 2006, 47, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada-Gómez, S.; Vargas Muñoz, L.J.; Saldarriaga-Córdoba, M.; Quintana Castillo, J.C. Venom from Opisthacanthus elatus scorpion of Colombia, could be more hemolytic and less neurotoxic than thought. Acta Trop. 2016, 153, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalapothakis, Y.; Miranda, K.; Aragão, M.; Larangote, D.; Braga-Pereira, G.; Noetzold, M.; Molina, D.; Langer, R.; Conceição, I.M.; Guerra-Duarte, C.; et al. Divergence in toxin antigenicity and venom enzymes in Tityus melici, a medically important scorpion, despite transcriptomic and phylogenetic affinities with problematic Brazilian species. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltan-Alinejad, P.; Alipour, H.; Meharabani, D.; Azizi, K. Therapeutic Potential of Bee and Scorpion Venom Phospholipase A2 (PLA2): A Narrative Review. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 47, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, É.R.; Mendes, T.M.; Magalhães, B.F.; Siqueira, F.F.; Dantas, A.E.; Barroca, T.M.; Horta, C.C.; Kalapothakis, E. Transcriptome analysis of the Tityus serrulatus scorpion venom gland. Open J. Genet. 2012, 2, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, D.A.; Dennis, E.A. The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A2 enzymes: Classification and characterization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1488, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jridi, I.; Catacchio, I.; Majdoub, H.; Shahbazzadeh, D.; El Ayeb, M.; Frassanito, M.A.; Solimando, A.G.; Ribatti, D.; Vacca, A.; Borchani, L. The small subunit of Hemilipin2, a new heterodimeric phospholipase A2 from Hemiscorpius lepturus scorpion venom, mediates the antiangiogenic effect of the whole protein. Toxicon 2017, 126, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incamnoi, P.; Patramanon, R.; Thammasirirak, S.; Chaveerach, A.; Uawonggul, N.; Sukprasert, S.; Rungsa, P.; Daduang, J.; Daduang, S. Heteromtoxin (HmTx), a novel heterodimeric phospholipase A2 from Heterometrus laoticus scorpion venom. Toxicon 2013, 61, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariprasad, G.; Singh, B.; Das, U.; Ethayathulla, A.S.; Kaur, P.; Singh, T.P.; Srinivasan, A. Cloning, sequence analysis and homology modeling of a novel phospholipase A2 from Heterometrus fulvipes (Indian black scorpion). DNA Seq. 2007, 18, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamudio, F.Z.; Conde, R.; Arévalo, C.; Becerril, B.; Martin, B.M.; Valdivia, H.H.; Possani, L.D. The mechanism of inhibition of ryanodine receptor channels by imperatoxin I, a heterodimeric protein from the scorpion Pandinus imperator. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 11886–11894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, R.; Zamudio, F.Z.; Becerril, B.; Possani, L.D. Phospholipin, a novel heterodimeric phospholipase A2 from Pandinus imperator scorpion venom. FEBS Lett. 1999, 460, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louati, H.; Krayem, N.; Fendri, A.; Aissa, I.; Sellami, M.; Bezzine, S.; Gargouri, Y. A thermoactive secreted phospholipase A₂ purified from the venom glands of Scorpio maurus: Relation between the kinetic properties and the hemolytic activity. Toxicon 2013, 72, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Meijden, A.; Coelho, P.; Rasko, M. Variability in venom volume, flow rate and duration in defensive stings of five scorpion species. Toxicon 2015, 100, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui Wen, F.; Monteiro, W.M.; Moura da Silva, A.M.; Tambourgi, D.V.; Mendonça da Silva, I.; Sampaio, V.S.; dos Santos, M.C.; Sachett, J.; Ferreira, L.C.; Kalil, J.; et al. Snakebites and scorpion stings in the Brazilian Amazon: Identifying research priorities for a largely neglected problem. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, W.M.; de Oliveira, S.S.; Pivoto, G.; Alves, E.C.; de Almeida Gonçalves Sachett, J.; Alexandre, C.N.; Fé, N.F.; Barbosa Guerra, M.; da Silva, I.M.; Tavares, A.M.; et al. Scorpion envenoming caused by Tityus cf. silvestris evolving with severe muscle spasms in the Brazilian Amazon. Toxicon 2016, 119, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.V.; Fé, N.F.; Santos, H.L.R.; Jung, B.; Bisneto, P.F.; Sachett, A.; de Moura, V.M.; Mendonça da Silva, I.; Cardoso de Melo, G.; Pereira de Oliveira Pardal, P.; et al. Clinical profile of confirmed scorpion stings in a referral center in Manaus, Western Brazilian Amazon. Toxicon 2020, 187, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, W.M.; Gomes, J.; Fé, N.; Mendonça da Silva, I.; Lacerda, M.; Alencar, A.; Seabra de Farias, A.; Val, F.; de Souza Sampaio, V.; Cardoso de Melo, G.; et al. Perspectives and recommendations towards evidence-based health care for scorpion sting envenoming in the Brazilian Amazon: A comprehensive review. Toxicon 2019, 169, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrez, P.P.; Quiroga, M.M.; Abati, P.A.; Mascheretti, M.; Costa, W.S.; Campos, L.P.; França, F.O. Acute cerebellar dysfunction with neuromuscular manifestations after scorpionism presumably caused by Tityus obscurus in Santarém, Pará/Brazil. Toxicon 2015, 96, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dintzis, H.M.; Dintzis, R.Z.; Vogelstein, B. Molecular determinants of immunogenicity: The immunon model of immune response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1976, 73, 3671–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higa, A.M. Propriedades Moleculares, Atividades Biológicas e Imunológicas das Toxinas Protéicas do Veneno de Brotheas amazonicus Lourenço, 1988 (Chactidae, Scorpiones); Universidade do Estado do Amazonas: Manaus, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schägger, H.; von Jagow, G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 166, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edman, P.; Begg, G. A Protein Sequenator. Eur. J. Biochem. 1967, 1, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consortium, U. UniProt: A hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D204–D212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiezel, G.A.; Oliveira, I.S.; Arantes, E.C. Simplifying traditional approaches for accessible analysis of snake venom enzymes. Toxicon 2025, 255, 108255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovic, N.; Grove, C.; Langton, P.E.; Misso, N.L.A.; Thompson, P.J. A simple assay for a human serum phospholipase A2 that is associated with high-density lipoproteins. J. Lipid Res. 2001, 42, 1706–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiezel, G.A.; Oliveira, I.S.; Ferreira, I.G.; Bordon, K.C.F.; Arantes, E.C. Hyperglycosylation impairs the inhibitory activity of rCdtPLI2, the first recombinant beta-phospholipase A2 inhibitor. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 280, 135581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, M.; Takahashi, T. A spectrophotometric microplate assay for L-amino acid oxidase. Anal. Biochem. 2001, 298, 136–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pukrittayakamee, S.; Warrell, D.; Desakorn, V.; McMichael, A.; White, N.; Bunnag, D. The hyaluronidase activities of some Southeast Asian snake venoms. Toxicon 1988, 26, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, W.; Prentice, C.R.M. The proteolytic action of ancrod on human fibrinogen and its polypeptide chains. Thromb. Res. 1973, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.S.; Pucca, M.B.; Wiezel, G.A.; Cardoso, I.A.; Bordon, K.C.F.; Sartim, M.A.; Kalogeropoulos, K.; Ahmadi, S.; Baiwir, D.; Nonato, M.C.; et al. Unraveling the structure and function of CdcPDE: A novel phosphodiesterase from Crotalus durissus collilineatus snake venom. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 178, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fraction | Subfraction | m/z * |

|---|---|---|

| 3–10 kDa | 8 | 688.0; 726.4; 766.5; 792.4; 845.4; 865.4; 909.0; 942.6; 966.5; 1005.7; 1049.7; 1129.7; 1157.8; 1181.8; 1225.8; 1269.8; 1313.9; 1357.9; 1397.9; 1446.0; 1490.0; 1528.0; 1556.1; 1572.0; 1600.1; 1618.1; 1644.1; 1660.1; 1688.2; 1704.1; 1732.2; 1748.2; 1792.1; 1837.2 |

| 9 | 866.5; 950.5; 972.5; 988.4; 1340.5; 1356.5; 1362.5; 1378.5; 1394.5; 1421.7 | |

| 24 | 790.5; 812.4; 828.4; 834.4; 850.4; 866.4; 877.1; 881.3; 919.5; 938.5; 957.5; 1075.7; 1110.7; 1132.7; 1148.7; 1163.7; 1189.6; 1215.9; 1230.7; 1237.8; 1253.8; 1387.8; 1403.7; 1413.7; 1423.8; 1651.9; 1673.9; 1689.8; 1705.8; 1711.8 | |

| 43 | 877.5; 887.7; 897.6; 913.6; 935.6; 951.6; 957.6; 973.6; 979.7; 993.8; 1002.7; 1084.7; 1126.8; 1191.0; 1213.0; 1228.9; 1247.9; 1269.8; 1275.8; 1285.8; 1402.9; 1413.9; 1420.9; 1440.9; 1442.9; 1458.9; 2013.5; 2058.6; 2072.5; 2169.7; 2994.8; 3321.4; 3321.7; 3337.4; 3337.7; 3463.8; 3464.1; 3634.3; 3634.6; 3704.7; 3720.5; 3720.8; 4159.9 | |

| 51 | 3003.0; 3304.4; 3359.9; 3445.8; 3671.7; 4154.7; 5567.7; 5556.8; 8357.6 | |

| 58 | 3072.1; 3089.1; 5727.7; 5742.9; 5754.9; 8617.5; 5731.1; 5744.0; 5757.9 (+2); 8617.2 | |

| 74 | 3302.2; 3055.5; 3968.9; 4064.0; 4673.4 | |

| 79 | 3413.9; 3643.6; 3655.8 | |

| 81 | 3089.1; 3089.3; 3378.9; 3379.2; 3394.0; 3596.6; 3610.6; 3845.4; 4179.2 | |

| 85 | 3421.0; 3433.0; 4319.1; 4333.1 | |

| 93 | 3878.8; 3894.7; 4063.1 | |

| >10 kDa | 5 | 800.3 |

| 9 | 794.5; 816.4; 832.4; 1165.7; 1177.7 | |

| 25 | 739.4; 761.4; 777.4; 993.6; 1304.7; 1417.7; 1455.7; 2275.4; 2407.4; 2468.8 (+2) | |

| 28 | 1427.7; 1449.7; 2316.3; 2331.1; 2353.1 | |

| 29 | 993.6; 1246.6; 1355.3 (+2); 1415.7; 1439.7; 1455.7; 2479.6; 2494.5; 2694.7; 2709.6; 2857.7; 2872.7; 3243.7 (+2) | |

| 30 | 1247.7; 1269.7; 1275.7; 1285.6; 1388.7; 1399.7; 1416.8; 1433.8; 1436.8 (+2); 1439.7; 1454.7; 1512.8; 1563.8; 2382.7; 2562.5; 2620.5; 2686.7; 2857.8; 2872.7 | |

| 59 | 3888.1; 4086.4 | |

| 6791.8; 9192.6; 13,382.9; 13,568.1; 13,582.6; 13,791.7 | ||

| 27,155.2; 27,384.1; 40,747.1 | ||

| 66 | 3325.3; 3335.6; 3350.6; 3367.6; 3789.8; 4270.8; 6250.0 | |

| 5565.5; 6252.9; 6597.9; 8099.3; 8108.8; 13,567.8; 13,583.8 | ||

| 81 | 4271.1; 4287.0; 5043.5; 5059.6; 5048.8; 5064.2; 5488.5; 13,581.5 | |

| 85 | no results |

| UniProt ID # | Previous Nomenclature * | Updated Nomenclature ** | Sequence 1234567890123 | Theoretical Molecular Mass (Da) ## |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P86341 | BaP-1 | BamazP-1 | IWSGIQGAF | 978 |

| P86340 | BaP-2 | BamazP-2 | IWSGIQSAF | 1008 |

| P86344 | BaP-3 | BamazP-3 | IGDIWSGIQG | 1045 |

| P86339 | BaP-4 | BamazP-4 | IIDFIPQIE | 1087 |

| P86343 | BaP-5 & | BamazP-5 | FIGDIWSGIQG | 1192 |

| P86342 | BaP-6 | BamazP-6 | GFIGDIWSGIQG | 1249 |

| P86338 | BaP-7 & | BamazP-7 | VAIRIIWSDIQD | 1429 |

| P86337 | BaP-8 & | BamazP-8 | ISDDIQSIIQGIF | 1449 |

| Subfraction | Automated de Novo Sequenced Peptide & | Deep Novo Score (%) | ALC (%) | Precursor | Precursor Mass Error (ppm) ## | PTM ** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m/z | z | ||||||

| 3–10 kDa | |||||||

| 9 | Q(+42.01)HGCGRAPT(−18.01) | 77 | 77 | 950.48 | 1 | 56.8 | Ac, D |

| 24 | SET(−18.01)ST(−18.01)PRS | 76.1 | 76.1 | 828.41 | 1 | 35.8 | D |

| 24 | FEFMWT(−18.01)P(−0.98) | 70.2 | 70.2 | 938.52 | 1 | 100.1 | Am, D |

| 24 | AAS(−18.01)EAALLLNR | 81.1 | 81.1 | 1110.69 | 1 | 61.4 | D |

| >10 kDa * | |||||||

| 9 | T(−17.03)PKRSLQ(−18.01) | 77.5 | 77.5 | 794.46 | 1 | 6.6 | Amm, D |

| 25 | E(−18.01)PRFLP(−0.98) | 86 | 86 | 739.42 | 1 | −8.1 | Am |

| 29 | CSGQTQFLVYEY(−18.01) | 75 | 75 | 1419.70 | 1 | 50.2 | D |

| Subfraction | Toxin Name | Protein Family | Sequence | Similarity [Accession Number] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <3 kDa | ||||

| 1 | - | - | LP ! | * |

| 4 | - | - | FGDS ! | * |

| 5 | - | - | F | * |

| 10 | BamazP-9 | NaTx | WAAIWXAW | putative Td8 [Q1I163|T. discrepans] |

| 3–10 kDa | ||||

| 43 | BamazP-10 | - | DLWSGISGN | BaP-3 [P86344|B. amazonicus]; BaP-5 [P86343|B. amazonicus]) |

| 51 | BamazP-11 BamazP-12 | - | YIPQDRFINWPVRGNPGVVHLHQ ! VGDEWTGRDGD | * transketolase 1 [GFR20058.1|Trichonephila clavata] |

| 58 | BamazP-13 | - | YIPQDDFFNNPVVGGNNPVVFHL | * |

| 67 | BamazP-14 | - | YIAELNNYVXPLTGIYXILA | * |

| 74 | BamazP-15 | - | DLWSGIKGAFLSNQDVP | Venom peptide 1 (BaP-1) [P86341|B. amazonicus] |

| 81 | BamazP-16 | NDBP | GILGTIWNGIXS | Pantinin-3 [R4JJN6|Pandinus imperator] |

| 83 | BamazP-17 | NDBP | GVAGPSVIGGL | Peptide TtAP-3 [P0DRB7|T. trinitatis] |

| 85 | BamazP-18 | lipase | TVWCPFKLGCMGTGTGTFPGFF ! | pancreatic lipase-related protein 2-like [XP_023235945.1|C. sculpturatus] |

| 87 | BamazP-19 | NDBP | GILSTLWSGIXSLF | Amphipathic peptide OcyC1 [C5J886|Opisthacanthus cayaporum] |

| 93 | BamazP-20 | - | VEFPLSVLXGXIXLS | * |

| >10 kDa | ||||

| 9 | BamazP-21 BamazP-35 | NaTx - | DCKYYGGXLNS RDVIES | Insectotoxin I2 (Toxin BeI2) [P15221|Mesobuthus eupeus] * |

| 13 | BamazMP-1 BamazMP-2 BamazP-26 | MP MP NDBP | QPNFLRNYDYKKYIPNNSVSYENNGTT GFTMNKYKQPFIPNNVVVYVSGGEERG ARDREIHAQIEQ | Tcis_Metallo_12 [WDU65926|T. cisandinus] Tcis_Metallo_11 [WDU65925|T. cisandinus] TsAP-1 [S6CWV8|T. serrulatus] |

| 25 | BamazP-32 BamazP-33 | - - | GKVGEFXVFNKQTLHGAPENAEQE LTAQKVANAAGDAYAYREYENQAQ | * * |

| 28 | BamazScplp2 | Sclp | HKISKMTEGFGCMANMDTRG SKMTEGFGCMANMDTRG | Scorpine [P56972|P. imperator] |

| 29 | BamazP-23 BamazP-24 | α-C6Tx α-C6Tx | FECEEXGNFQDPDDXSXFIXCDNNXK FECEEXGHFQDPDDXSXFIXCDNNXK (equitable isoforms) | venom peptide HtC6Tx2 [AOF40177|Hadogenes troglodytes] |

| 30 | BamazP-25 BamazSclp3 | KTx Sclp | VLFETKPETQG ! (determined through MS spectrum) GKLSKMTEGFGCMANMDVMG ! | putative KTx [WLF82719|T. melici] Scorpine [P56972|P. imperator] |

| 32 | BamazP-27 | - | AELSWMTEGFGA | * |

| 36 | BamazP-28 BamazP-29 BamazP-30 BamazP-31 | KTx KTx KTx KTx | GLTELGVQDYICNCFPAALQRPA GLTEKGVQDYICNCFPAALQRPA GLTELNVQDYICNCFPAALQYPA GLTEKNVQDYICNCFPAALQYPA | U9-buthitoxin-Hj2a [ADY39508|Hottentotta judaicus] U9-buthitoxin-Hj2a [ADY39508|Hottentotta judaicus] |

| 49 | BamazMP-5 BamazMP-6 | MP MP | TMLTGITKMYNELGARILKAGAAGNI GKRGSYFGAVICSIRVLNIEKQKKG | Tcis_Meta llo_6 [WDU65920|T. cisandinus] disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10-like [XP_023240311.1|C. sculpturatus] |

| 54 | BamazP-22 BamazP-36 | - - | AMVSQIPKLYKEITNMILQAVKAVGKMDMALSMGMISDFR TLXDEXDGVPRIVGRRMHEXAXKEAIDPADXTKEXGYALV | * * |

| 59 | BamazScplp1 BamazPLA2 | Sclp PLA2 | GLIKEQYFHKANDSLSYLIPKPVVNKLVGNAAXQMIHXIGXVQ TVWGTXWCGAGNESTDYXELGYFNDADRCCRXH | C0HME9 C0HMF5 |

| 59E | BamazP-39 | - | XEICLQYFTGE | Venom protein 214 [P0CJ10|Lychas mucronatus] |

| 66 | BamazMP-8 BamazMP-9 | MP MP | GFDXXSNIGSALREFIMSMGVATLAGQAL DLCXXTDASLMENXSYVAYAKGNYPNEVA | A disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs 5 [GBM47826.1|A. ventricosus] |

| 70 | BamazP-38 BamazMP-7 | - MP | GILRIIWSDIRDVFGCQGLRN FWGRIAWEATEERPRCE | BaP-7 [P86338|B. amazonicus] astacin-like metalloprotease toxin 5 [XP_023232131.1|C. sculpturatus] |

| 71–72 | BamazP-34 BamazAmy | AMP Amylase | AKVMLVCLAIXIIPGLVGGLISAXK !** WVVRVYW ! | Con22 precursor [L0GBQ6|Urodacus yaschenkoi]; ToAP3 [P0DQT2|T. obscurus] α-amylase-like [XP_067140601.1|C. vittatus] |

| 73 | - | - | # | * |

| 74 | - | - | # | * |

| 75 | - | - | # | * |

| 77 | BamazP-37 | NDBP | PKKYKYK | Venom protein 22.1 [P0CJ04|Lychas mucronatus] |

| 81 | BamazMP-4 | MP | KLIRDENQAREFHLNLDEKMVKA | disintegrin and metalloproteinase [AMO02516|T. serrulatus] |

| 83 | - | - | # | * |

| 85 | BamazMP-3 | MP | QDVDSCNSYTRFV | astacin-like metalloprotease toxin 1 [XP_023230424|Centruroides sculpturatus] |

| 89 | BamazChi | Chitinase | DDVDP | probable chitinase 10 [XP_023236728|C. sculpturatus] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wiezel, G.A.; Bordon, K.d.C.F.; Martins, J.G.; Custódio, V.I.d.C.; Matsuno, A.K.; Procópio, R.E.d.L.; Arantes, E.C. A Hydrolase-Rich Venom Beyond Neurotoxins: Integrative Functional Proteomic and Immunoreactivity Analyses Reveal Novel Peptides in the Amazonian Scorpion Brotheas amazonicus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031475

Wiezel GA, Bordon KdCF, Martins JG, Custódio VIdC, Matsuno AK, Procópio REdL, Arantes EC. A Hydrolase-Rich Venom Beyond Neurotoxins: Integrative Functional Proteomic and Immunoreactivity Analyses Reveal Novel Peptides in the Amazonian Scorpion Brotheas amazonicus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031475

Chicago/Turabian StyleWiezel, Gisele Adriano, Karla de Castro Figueiredo Bordon, Jonas Gama Martins, Viviane Imaculada do Carmo Custódio, Alessandra Kimie Matsuno, Rudi Emerson de Lima Procópio, and Eliane Candiani Arantes. 2026. "A Hydrolase-Rich Venom Beyond Neurotoxins: Integrative Functional Proteomic and Immunoreactivity Analyses Reveal Novel Peptides in the Amazonian Scorpion Brotheas amazonicus" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031475

APA StyleWiezel, G. A., Bordon, K. d. C. F., Martins, J. G., Custódio, V. I. d. C., Matsuno, A. K., Procópio, R. E. d. L., & Arantes, E. C. (2026). A Hydrolase-Rich Venom Beyond Neurotoxins: Integrative Functional Proteomic and Immunoreactivity Analyses Reveal Novel Peptides in the Amazonian Scorpion Brotheas amazonicus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031475