Exploratory Cytokine and Bone-Marker Patterns in a Proteoglycan-Induced Spondyloarthritis Mouse Model: Th1/Th2 Strain Comparison and TLR2/3/4 Knockout Readouts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

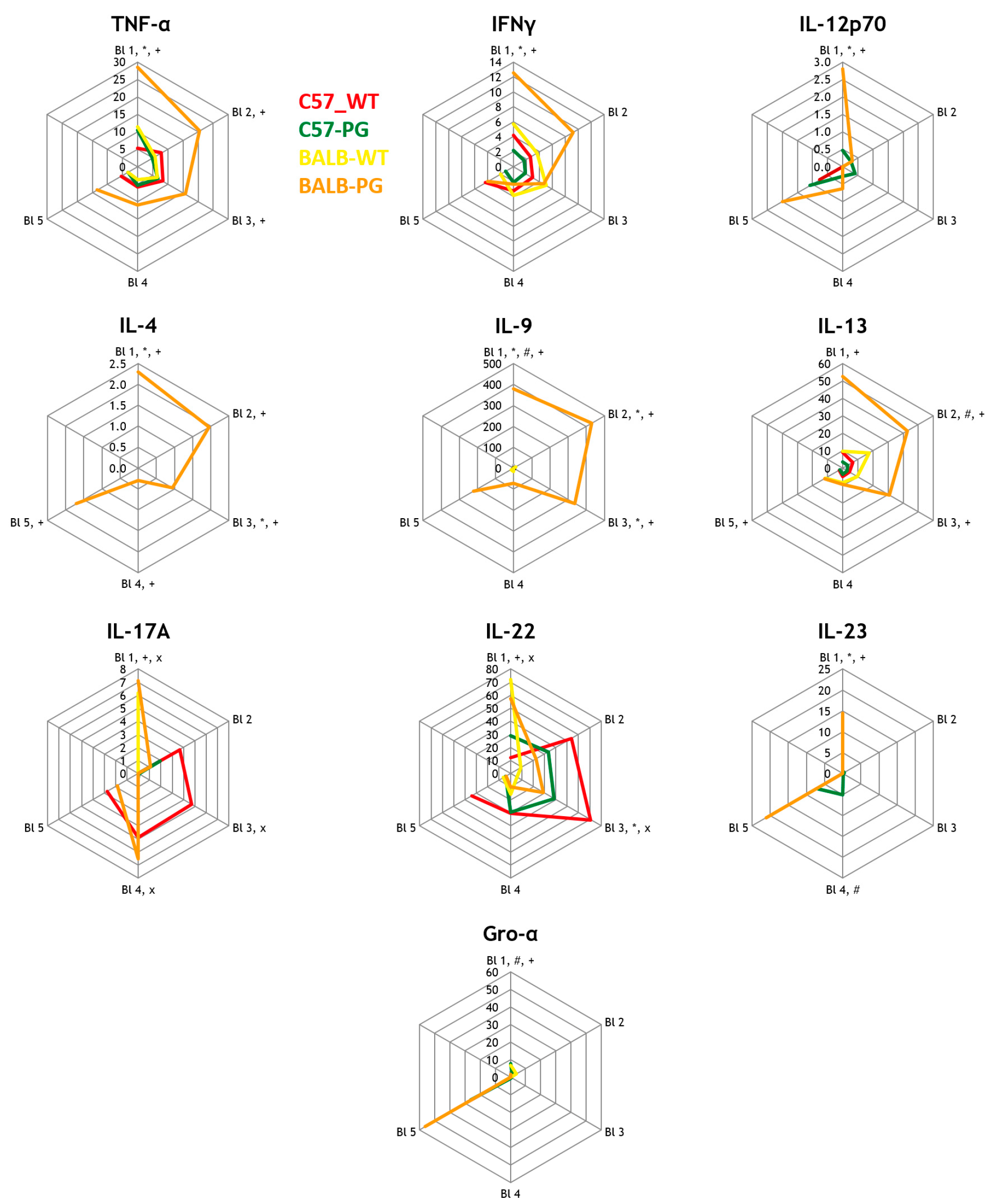

2.1. Strain Effect (Immunized): C57-PG vs. BALB-PG (With Non-Immunized Controls)—Th1/Th2/Th17 Cytokines

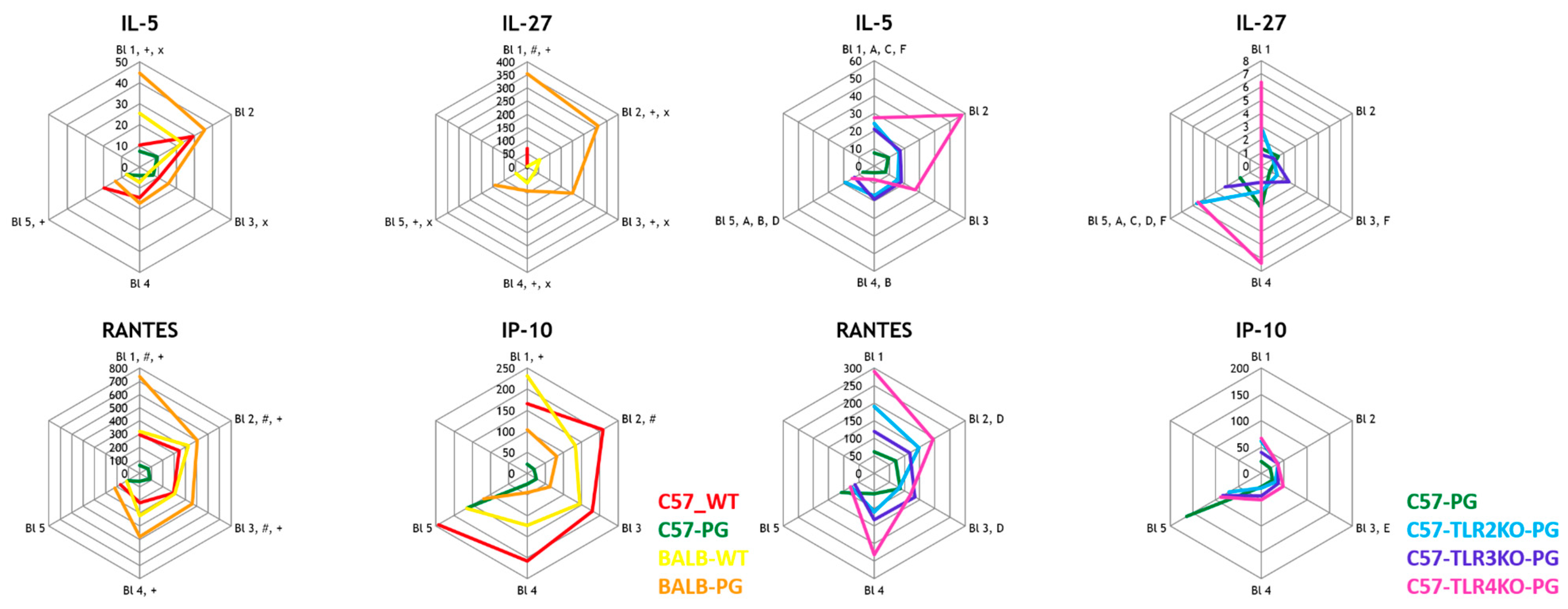

2.2. Strain Effect (C57-PG vs. BALB-PG) and TLR Effect (C57-PG vs. C57-TLRxKO-PG) on Eosinophil-Associated Cytokines

2.3. TLR Effect (Immunized C57 Background): C57-PG vs. C57-TLR2/3/4KO-PG—Adaptive Cytokines

2.4. Strain Effect (C57-PG vs. BALB-PG) and TLR Effect (C57-PG vs. C57-TLRxKO-PG) on Macrophage-Associated Cytokines

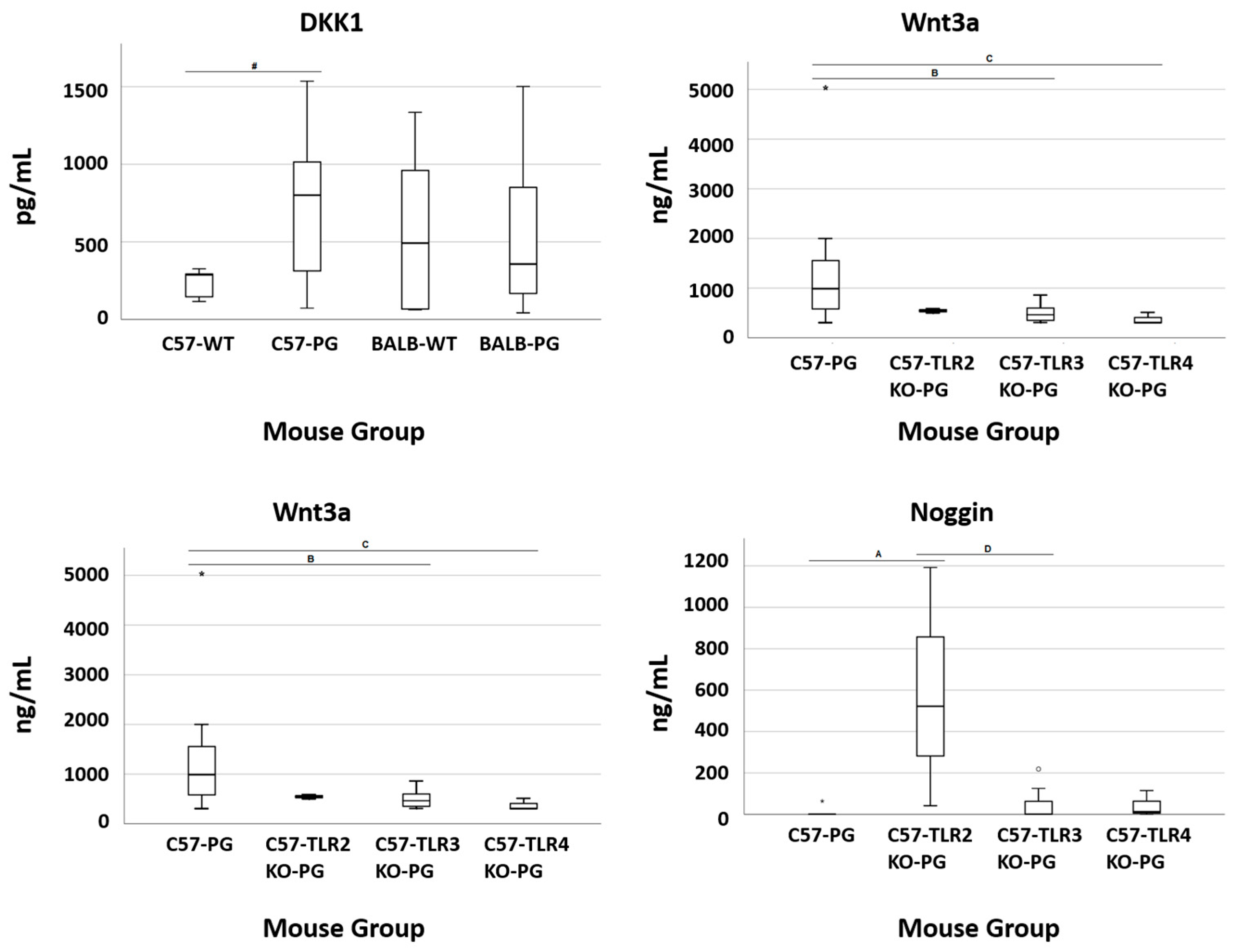

2.5. TLR Effect (Terminal Serum Bone Markers): C57-PG vs. C57-TLR2/3/4KO-PG

3. Discussion

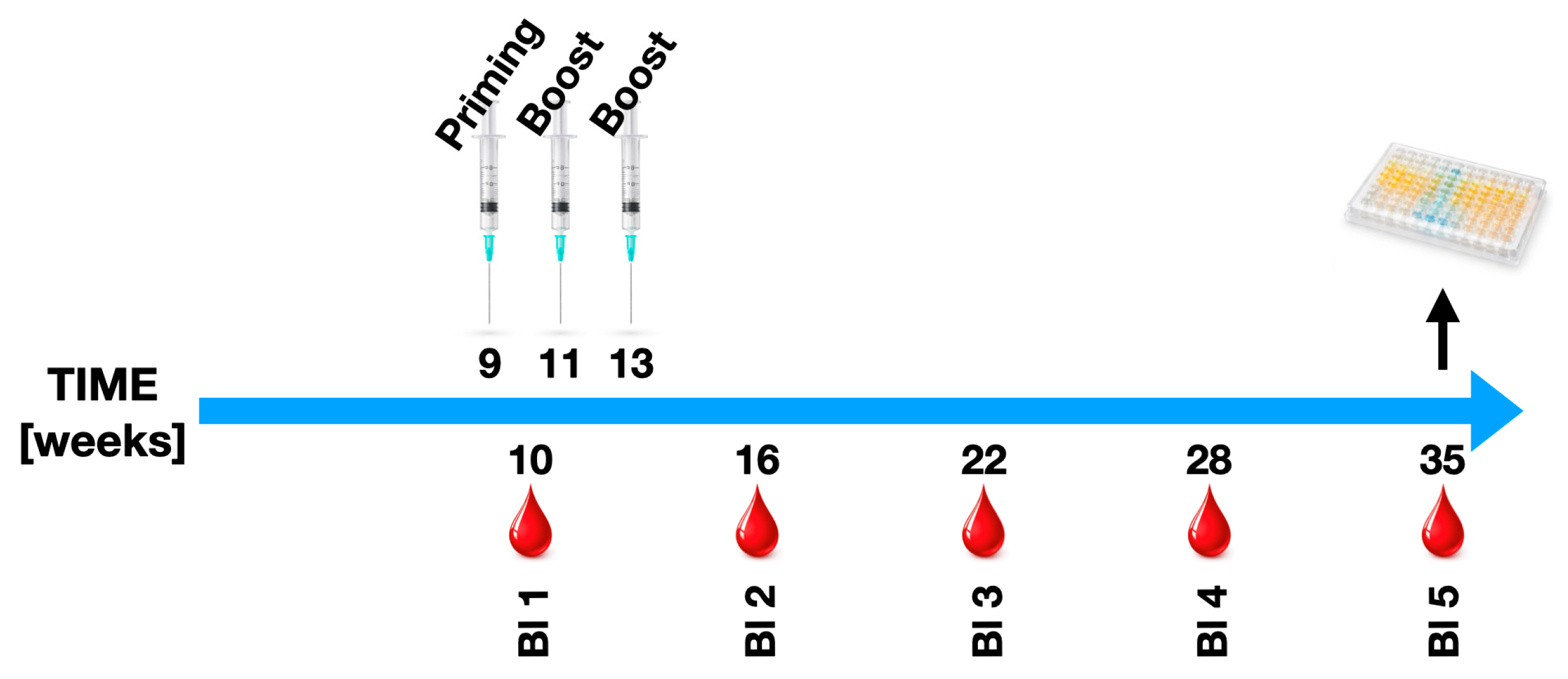

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Mouse Models for Spondyloarthritis

4.2. Quantification of Cytokines and Other Biomarkers

4.3. Statistical Considerations

4.4. Ethical Considerations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AS | Ankylosing Spondylitis |

| AUC | Area Under the-Curve |

| BALB/c | Bagg Albino Laboratory-Bred Strain c (Th2-prone mouse strain) |

| BMP | Bone Morphogenetic Protein |

| C57BL/6J | Inbred C57 Black 6J Mouse Strain (Th1-prone) |

| CFA/IFA | Complete/Incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CXCL1/Gro-α | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) Ligand 1/Growth-Regulated Oncogene Alpha |

| DKK-1 | Dickkopf-related Protein 1 |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| ERAP1/2 | Endoplasmic Reticulum Aminopeptidase 1 and 2 |

| ESR | Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| GEE | Generalized Estimating Equation |

| HLA-B27 | Human Leukocyte Antigen B27 |

| HR-pQCT | High-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography |

| IFA | Incomplete Freund’s Adjuvant |

| IFNγ | Interferon Gamma |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IL-23R | Interleukin-23 Receptor |

| IP-10 | Interferon Gamma-Induced Protein 10 (CXCL10) |

| KO | Knockout |

| MCP-1/3 | Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1 and 3 |

| MHC | Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| MIP-1α/β/2 | Macrophage Inflammatory Protein 1 alpha, 1 beta, and 2 |

| MΦ | Macrophage |

| NK | Natural Killer (cell) |

| pg/mL | Picogram per Milliliter |

| pQCT | Peripheral Quantitative Computed Tomography |

| RANTES | Regulated upon Activation, Normal T Cell Expressed and Secreted (CCL5) |

| RORγt | Retinoic Acid Receptor-Related Orphan Receptor Gamma t |

| SEM | Standard Error of the Mean |

| SpA | Spondyloarthritis |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor Beta |

| Th1/Th2/Th17 | T-helper Cell Type 1, 2, and 17 |

| TLR | Toll-like Receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| UPR | Unfolded Protein Response |

| WT | Wild-Type |

| Wnt3a | Wingless-Type MMTV Integration Site Family Member 3A |

Appendix A. Power Considerations (Minimal Detectable Effects)

- C57BL/6J WT immunized (n = 16) vs. BALB/c WT immunized (n = 9): d ≈ 1.22

- TLR2-KO (n = 7) vs. C57BL/6J WT immunized (n = 16): d ≈ 1.33

- TLR3-KO (n = 8) vs. C57BL/6J WT immunized (n = 16): d ≈ 1.27

- TLR4-KO (n = 3) vs. C57BL/6J WT immunized (n = 16): d ≈ 1.87

References

- Stolwijk, C.; van Onna, M.; Boonen, A.; van Tubergen, A. Global Prevalence of Spondyloarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2016, 68, 1320–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parma, A.; Cometi, L.; Leone, M.C.; Lepri, G.; Talarico, R.; Guiducci, S. One year in review 2016: Spondyloarthritis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2017, 35, 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Colbert, R.A.; Tran, T.M.; Layh-Schmitt, G. HLA-B27 misfolding and ankylosing spondylitis. Mol. Immunol. 2014, 57, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravallese, E.M.; Schett, G. Effects of the IL-23-IL-17 pathway on bone in spondyloarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2018, 14, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duftner, C.; Goldberger, C.; Falkenbach, A.; Würzner, R.; Falkensammer, B.; Pfeiffer, K.P.; Maerker-Hermann, E.; Schirmer, M. Prevalence, clinical relevance and characterization of circulating cytotoxic CD4+CD28- T cells in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2003, 5, R292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantino, F.; Breban, M.; Garchon, H.J. Genetics and Functional Genomics of Spondyloarthritis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdaca, G.; Negrini, S.; Magnani, O.; Penza, E.; Pellecchio, M.; Gulli, R.; Mandich, P.; Puppo, F. Update upon efficacy and safety of etanercept for the treatment of spondyloarthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Mod. Rheumatol. 2018, 28, 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, A.B.; Deodhar, A.; McInnes, I.B.; Baraliakos, X.; Reich, K.; Schreiber, S.; Bao, W.; Marfo, K.; Richards, H.B.; Pricop, L.; et al. Long-term Safety of Secukinumab Over Five Years in Patients with Moderate-to-severe Plaque Psoriasis, Psoriatic Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis: Update on Integrated Pooled Clinical Trial and Post-marketing Surveillance Data. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2022, 102, adv00698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchlin, C.; Rahman, P.; Kavanaugh, A.; McInnes, I.B.; Puig, L.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y.K.; Doyle, M.K.; Mendelsohn, A.M.; et al. Efficacy and safety of the anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite conventional non-biological and biological anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy: 6-month and 1-year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised PSUMMIT 2 trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 990–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherlock, J.P.; Joyce-Shaikh, B.; Turner, S.P.; Chao, C.C.; Sathe, M.; Grein, J.; Gorman, D.M.; Bowman, E.P.; McClanahan, T.K.; Yearley, J.H.; et al. IL-23 induces spondyloarthropathy by acting on ROR-γt+ CD3+CD4-CD8- entheseal resident T cells. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zayadi, A.A.; Jones, E.A.; Churchman, S.M.; Baboolal, T.G.; Cuthbert, R.J.; El-Jawhari, J.J.; Badawy, A.M.; Alase, A.A.; El-Sherbiny, Y.M.; McGonagle, D. Interleukin-22 drives the proliferation, migration and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells: A novel cytokine that could contribute to new bone formation in spondyloarthropathies. Rheumatology 2017, 56, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauli, A.; Mathieu, A. Th17 and interleukin 23 in the pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis and spondyloarthritis. J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 2012, 89, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duftner, C.; Dejaco, C.; Kullich, W.; Klauser, A.; Goldberger, C.; Falkenbach, A.; Schirmer, M. Preferential type 1 chemokine receptors and cytokine production of CD28- T cells in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2006, 65, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westendorf, J.J.; Kahler, R.A.; Schroeder, T.M. Wnt signaling in osteoblasts and bone diseases. Gene 2004, 341, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiland, G.R.; Appel, H.; Poddubnyy, D.; Zwerina, J.; Hueber, A.; Haibel, H.; Baraliakos, X.; Listing, J.; Rudwaleit, M.; Schett, G.; et al. High level of functional dickkopf-1 predicts protection from syndesmophyte formation in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2012, 71, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lories, R.J.; Luyten, F.P.; de Vlam, K. Progress in spondylarthritis. Mechanisms of new bone formation in spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2009, 11, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, K. Toll-like receptors in immunity and inflammatory diseases: Past, present, and future. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 59, 391–412, Correction in Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 62, 338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2018.03.002. [Google Scholar]

- Raffeiner, B.; Dejaco, C.; Duftner, C.; Kullich, W.; Goldberger, C.; Vega, S.C.; Keller, M.; Grubeck-Loebenstein, B.; Schirmer, M. Between adaptive and innate immunity: TLR4-mediated perforin production by CD28null T-helper cells in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2005, 7, R1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, M.; Jorgensen, A.L.; Kolamunnage-Dona, R. Biomarker-Guided Adaptive Trial Designs in Phase II and Phase III: A Methodological Review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benfaremo, D.; Luchetti, M.M.; Gabrielli, A. Biomarkers in Inflammatory Bowel Disease-Associated Spondyloarthritis: State of the Art and Unmet Needs. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 8630871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.A.; Colbert, R.A. Review: The interleukin-23/interleukin-17 axis in spondyloarthritis pathogenesis: Th17 and beyond. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.K.; Choi, J.; Lee, S.Y.; Seo, H.B.; Jung, K.; Na, H.S.; Ryu, J.G.; Kwok, S.K.; Cho, M.L.; Park, S.H. Protein inhibitor of activated STAT3 reduces peripheral arthritis and gut inflammation and regulates the Th17/Treg cell imbalance via STAT3 signaling in a mouse model of spondyloarthritis. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breban, M.; Araujo, L.M.; Chiocchia, G. Animal models of spondyloarthritis: Do they faithfully mirror human disease? Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014, 66, 1689–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glant, T.T.; Mikecz, K.; Arzoumanian, A.; Poole, A.R. Proteoglycan-induced arthritis in BALB/c mice. Clinical features and histopathology. Arthritis Rheum. 1987, 30, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feltelius, N.; Hallgren, R.; Venge, P. Raised circulating levels of the eosinophil cationic protein in ankylosing spondylitis: Relation with the inflammatory activity and the influence of sulphasalazine treatment. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1987, 46, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargin, G.; Senturk, T.; Yavasoglu, I. The relationship between blood eosinophil count and disease activity in ankylosing spondylitis patients treated with TNF-alpha inhibitors. Saudi Pharm. J. 2018, 26, 943–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, J.; Rothenberg, M.E. Eosinophils in mucosal immune responses. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 464–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, M.E.; Munitz, A.; Ackerman, S.J.; Drake, M.G.; Jackson, D.J.; Wardlaw, A.J.; Dougan, S.K.; Berdnikovs, S.; Schleich, F.; Matucci, A.; et al. Eosinophils in Health and Disease: A State-of-the-Art Review. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 2694–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, H.F.; Dyer, K.D.; Foster, P.S. Eosinophils: Changing perspectives in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárdos, T.; Szabó, Z.; Czipri, M.; Vermes, C.; Tunyogi-Csapó, M.; Urban, R.M.; Mikecz, K.; Glant, T.T. A longitudinal study on an autoimmune murine model of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005, 64, 981–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynn, T.A. Type 2 cytokines: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouro, T.; Takatsu, K. IL-5- and eosinophil-mediated inflammation: From discovery to therapy. Int. Immunol. 2009, 21, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Guo, S.; Hibbert, J.M.; Jain, V.; Singh, N.; Wilson, N.O.; Stiles, J.K. CXCL10/IP-10 in infectious diseases pathogenesis and potential therapeutic implications. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011, 22, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Xu, F.; Huang, S.; Xiang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Ren, G. IL-27 Is Elevated in Patients With COPD and Patients With Pulmonary TB and Induces Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells to Produce CXCL10. Chest 2012, 141, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, L.F.; Mathiak, G.; Bagasra, O. The immunobiology of interferon-gamma inducible protein 10 kD (IP-10): A novel, pleiotropic member of the C-X-C chemokine superfamily. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997, 8, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudwaleit, M.; Andermann, B.; Alten, R.; Sörensen, H.; Listing, J.; Zink, A.; Sieper, J.; Braun, J. Atopic disorders in ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2002, 61, 968–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, F.; Deodhar, A. Treatment of spondyloarthritis beyond TNF-alpha blockade. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2014, 28, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.J.; Maksymowych, W.P. The Pathogenesis of Ankylosing Spondylitis: An Update. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2019, 21, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, Y.; Pan, F.; Gao, J.; Ge, R.; Duan, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Liao, F.; Xia, G.; Wang, S.; Xu, S.; et al. Increased serum IL-17 and IL-23 in the patient with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2011, 30, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, H.; Koca, S.S.; Ozgen, M.; Isik, A. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies reduce serum macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha in ankylosing spondylitis. J. Rheumatol. 2010, 37, 1073–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekpa, F.K.; Poulain, C.; Wendling, D.; Soubrier, M.; De Bandt, M.; Berthelot, J.M.; Gaudin, P.; Toussirot, E.; Goupille, P.; Pham, T.; et al. Is IL-6 an appropriate target to treat spondyloarthritis patients refractory to anti-TNF therapy? A multicentre retrospective observational study. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012, 14, R53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocturne, G.; Pavy, S.; Boudaoud, S.; Seror, R.; Goupille, P.; Chanson, P.; van der Heijde, D.; van Gaalen, F.; Berenbaum, F.; Mariette, X.; et al. Increase in Dickkopf-1 Serum Level in Recent Spondyloarthritis. Data from the DESIR Cohort. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozato, K.; Tsujimura, H.; Tamura, T. Toll-like receptor signaling and regulation of cytokine gene expression in the immune system. Biotechniques 2002, 33, S66–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulendran, B.; Kumar, P.; Cutler, C.W.; Mohamadzadeh, M.; Van Dyke, T.; Banchereau, J. Lipopolysaccharides from distinct pathogens induce different classes of immune responses in vivo. J. Immunol. 2001, 167, 5067–5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, K.; Pallua, J.D.; Degenhart, G.; De Zordo, T.; Kremser, C.; Reif, C.; Streif, W.; Schirmer, M. Reduced Bone Quality of Sacrum and Lumbal Vertebrae Spongiosa in Toll-like Receptor 2- and Toll-like Receptor 4-Knockout Mice: A Blinded Micro-Computerized Analysis. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strain | Genotype | Immunization | Size (n) | Sex (M/F) | Purpose of Inclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | WT | No | 7 | 7/0 | Th2-prone control group as baseline reference |

| BALB/c | WT | Yes * | 9 | 9/0 | Th2-prone model of induced SpA |

| C57BL/6J | WT | No | 8 | 8/0 | Th1-prone control group as baseline reference |

| C57BL/6J | WT | Yes * | 16 | 16/0 | Th1-prone model of induced SpA |

| C57BL/6J | TLR2-KO | Yes * | 7 | 7/0 | Th1-prone TLR2-KO mice to study role of TLR2 |

| C57BL/6J | TLR3-KO | Yes * | 8 | 8/0 | Th1-prone TLR3-KO mice to study role of TLR3 |

| C57BL/6J | TLR4-KO | Yes * | 3 | 3/0 | Th1-prone TLR4-KO mice to study role of TLR4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pallua, J.D.; Schirmer, M. Exploratory Cytokine and Bone-Marker Patterns in a Proteoglycan-Induced Spondyloarthritis Mouse Model: Th1/Th2 Strain Comparison and TLR2/3/4 Knockout Readouts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031337

Pallua JD, Schirmer M. Exploratory Cytokine and Bone-Marker Patterns in a Proteoglycan-Induced Spondyloarthritis Mouse Model: Th1/Th2 Strain Comparison and TLR2/3/4 Knockout Readouts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031337

Chicago/Turabian StylePallua, Johannes Dominikus, and Michael Schirmer. 2026. "Exploratory Cytokine and Bone-Marker Patterns in a Proteoglycan-Induced Spondyloarthritis Mouse Model: Th1/Th2 Strain Comparison and TLR2/3/4 Knockout Readouts" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031337

APA StylePallua, J. D., & Schirmer, M. (2026). Exploratory Cytokine and Bone-Marker Patterns in a Proteoglycan-Induced Spondyloarthritis Mouse Model: Th1/Th2 Strain Comparison and TLR2/3/4 Knockout Readouts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1337. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031337