Monitoring Nanoparticle Interaction with Murine Breast Cancer Cells Using Multimodal Fluorescence Lifetime Microscopy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Inorganic-Organic Hybrid Nanoparticles (IOH-NPs)

1.2. Multimodal Fluorescence Lifetime Microscopy

2. Results

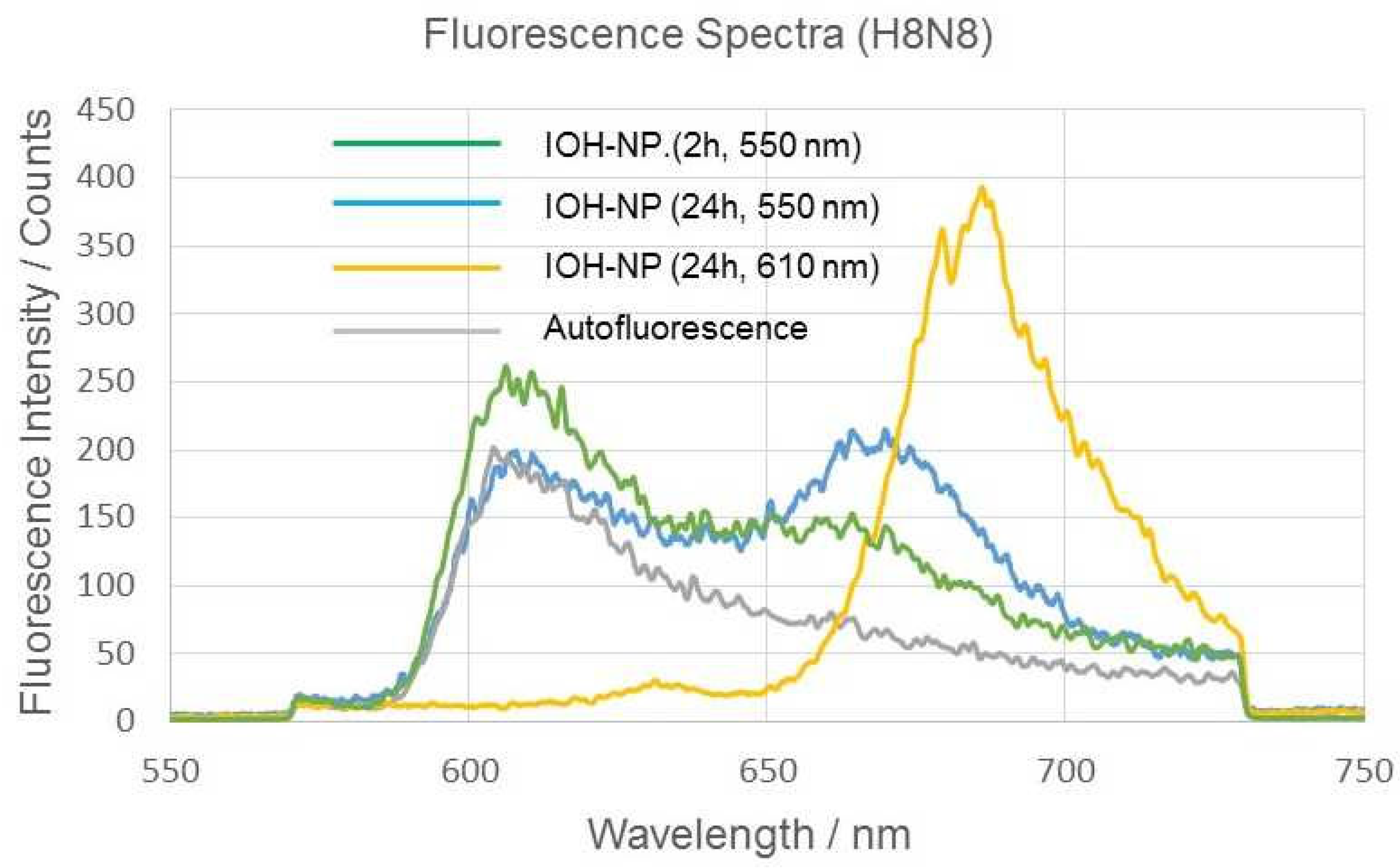

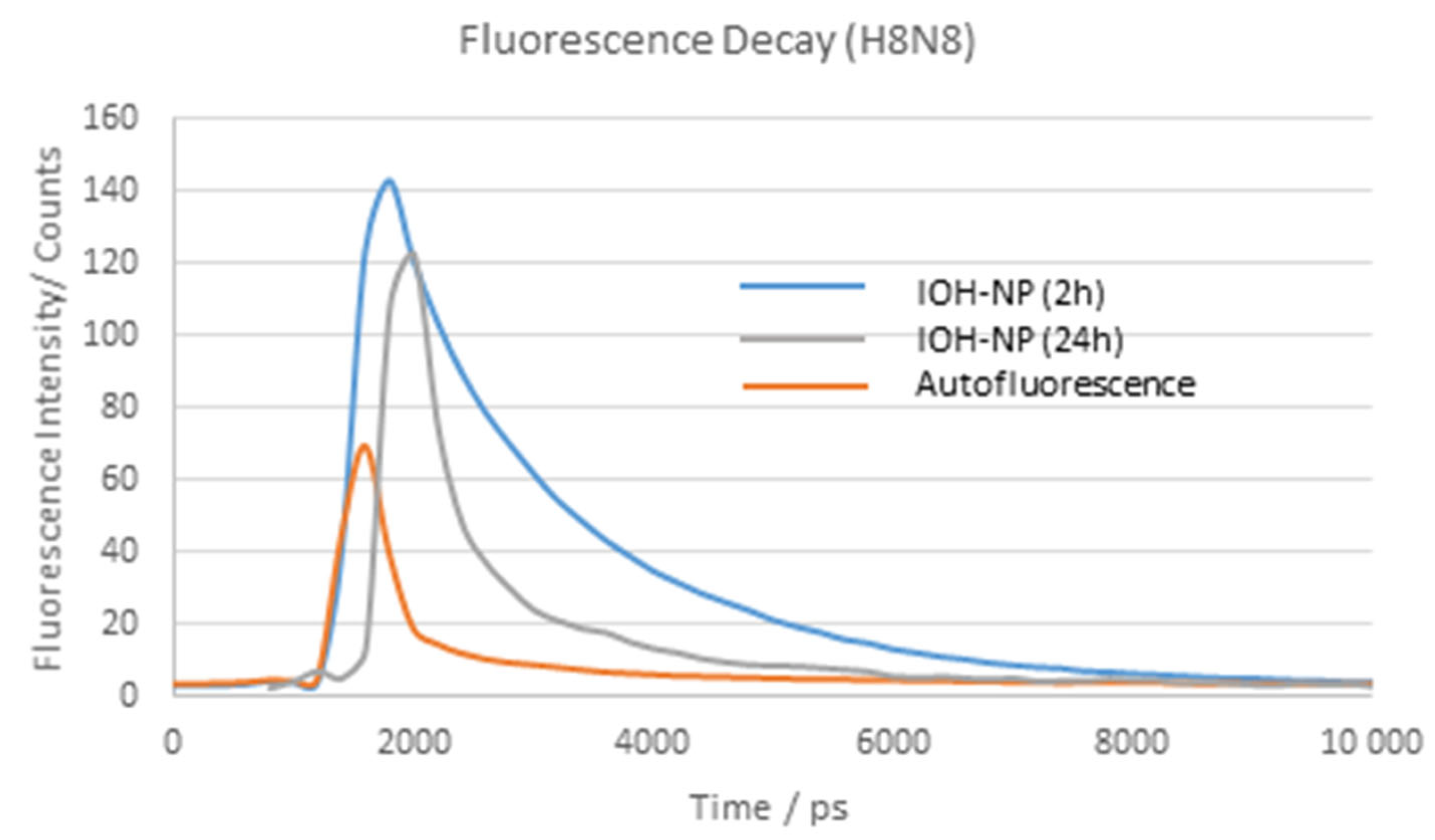

2.1. Time-Dependent Fluorescence Lifetime and Spectroscopy Experiments

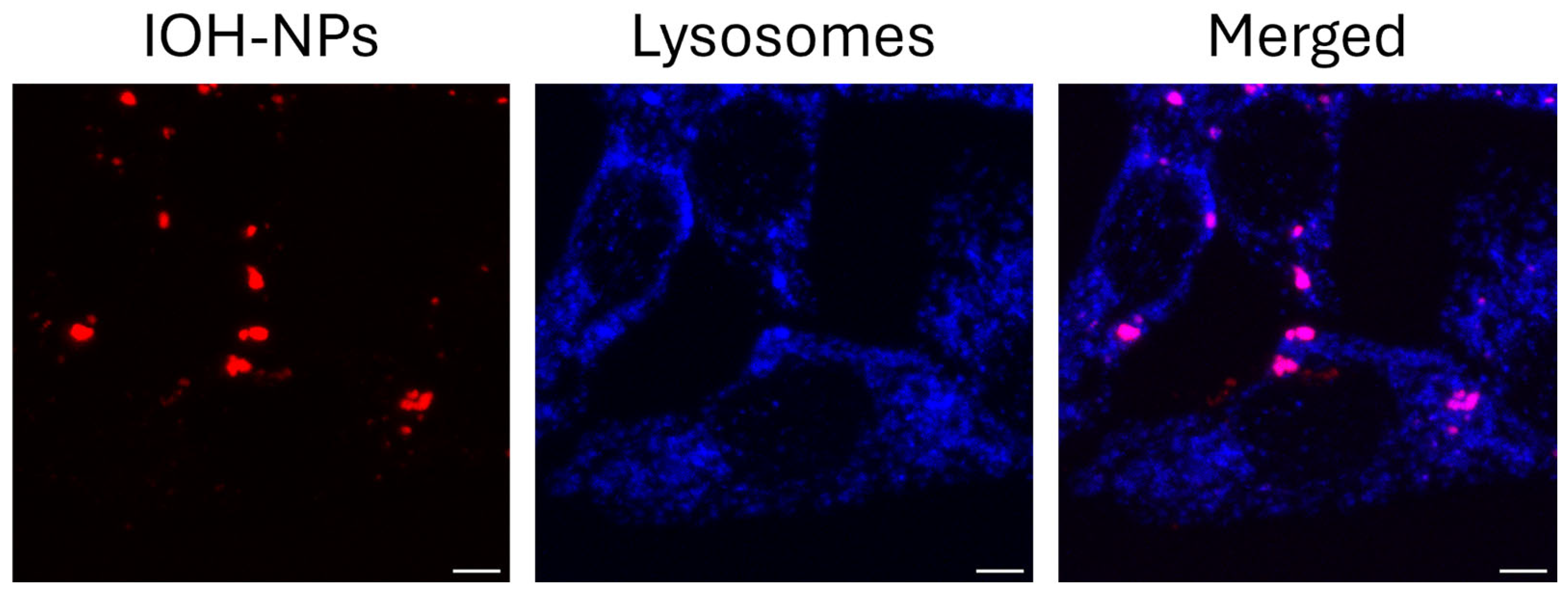

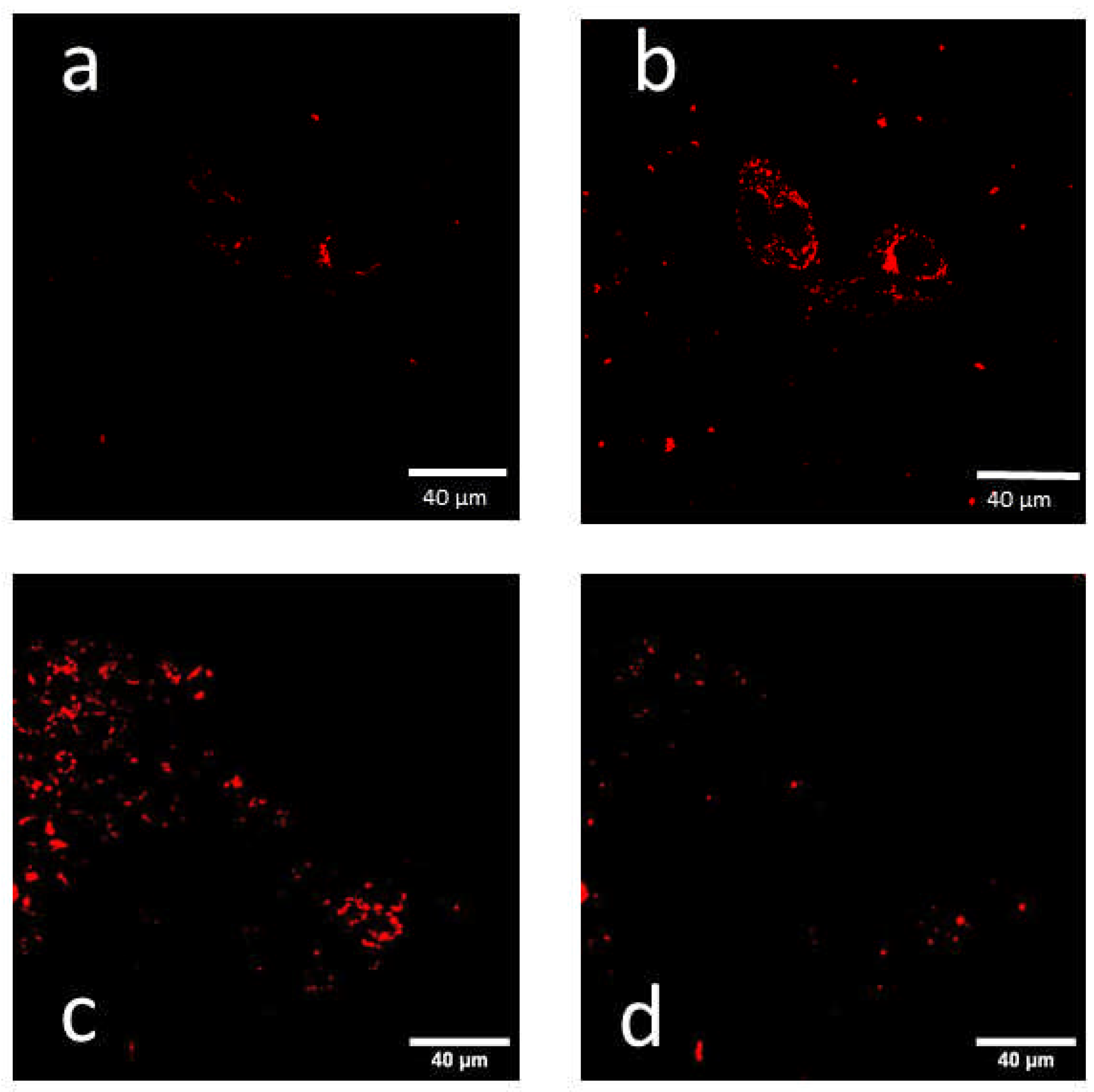

2.2. Fluorescence Lifetime Images

2.3. Influence of the LysoTracker Green on IOH-NPs

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture of H8N8 Cells

4.2. IOH-NPs

4.3. Confocal Imaging

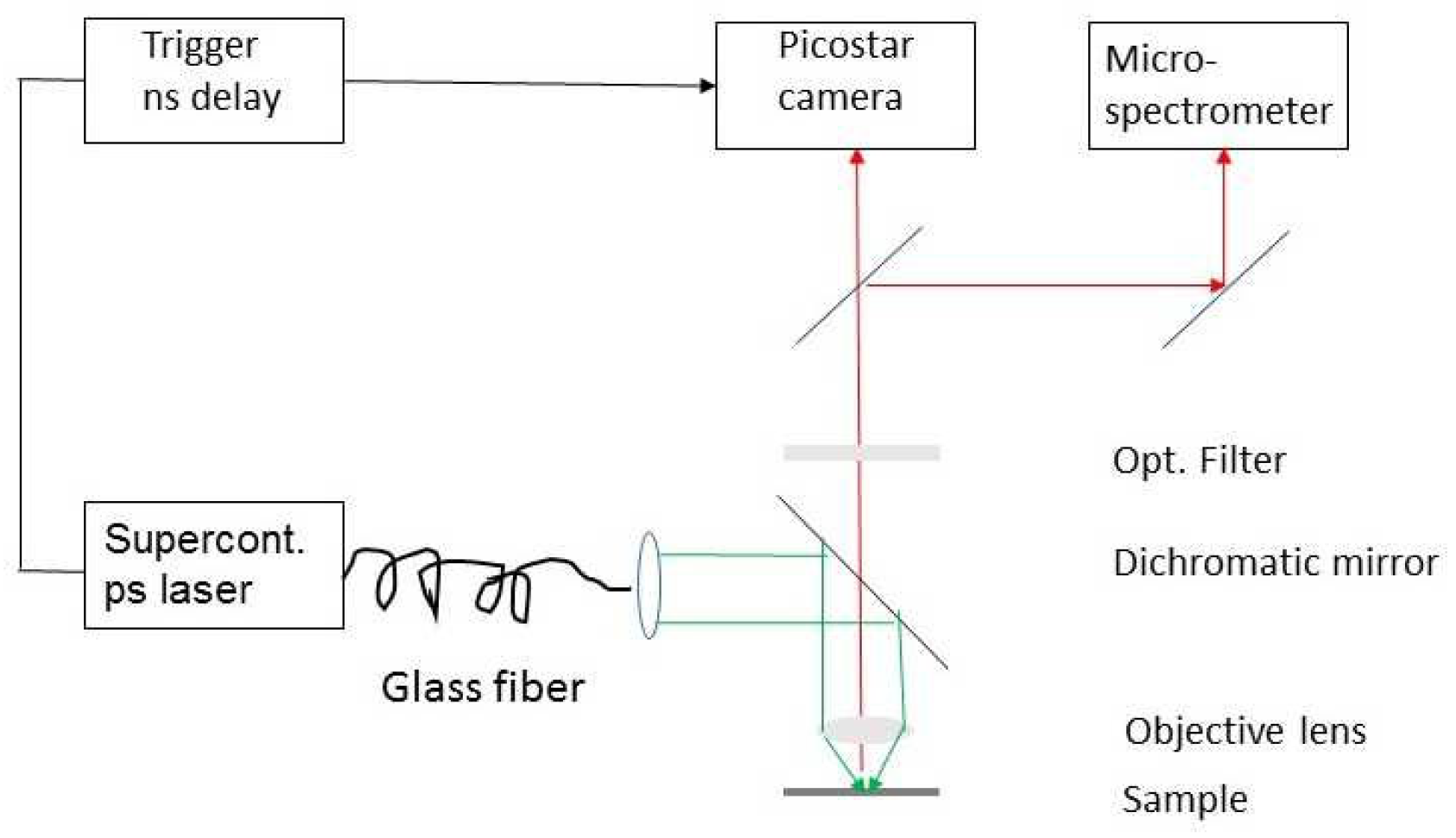

4.4. Fluorescence Lifetime and Microspectrometry Experiments

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IOH-NPs | Inorganic–organic hybrid nanoparticles |

| CLEM | Correlative light and electron microscopy |

| FRET | Förster resonance energy transfer |

| FLIM | Fluorescence lifetime imaging (microscopy) |

| C-LSM | Confocal laser scanning microscopy |

| TIR(FM) | Total internal reflection (fluorescence microscopy) |

| MADs | Median absolute deviations |

References

- Heck, J.G.; Napp, J.; Simonato, S.; Möllmer, J.; Lange, M.; Reichardt, H.M.; Staudt, R.; Alves, F.; Feldmann, C. Multifunctional phosphate-based inorganic-organic hybrid nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7329–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ischyropoulou, M.; Sabljo, K.; Schneider, L.; Niemeyer, C.M.; Napp, J.; Feldmann, C.; Alves, F. High-Load Gemcitabine Inorganic-Organic Hybrid Nanoparticles as an Image-Guided Tumor-Selective Drug-Delivery System to Treat Pancreatic Cancer. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2305151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorenko, M.; Pfeifer, J.; Napp, J.; Meschkov, A.; Alves, F.; Schepers, U.; Feldmann, C. Theranostic inorganic-organic hybrid nanoparticles with a cocktail of chemotherapeutic and cytostatic drugs. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 3635–3649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabljo, K.; Ischyropoulou, M.; Napp, J.; Alves, F.; Feldmann, C. High-load nanoparticles with a chemotherapeutic SN-38/FdUMP drug cocktail. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 14853–14860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbsleb, L.; Wild, D.; Gröger, H.; Schubert, T.; Steyer, A.M.; Hennies, J.; Alves, F.; Feldmann, C.; Walter, A. 3D correlative light and electron microscopy reveals the uptake and processing of inorganic-organic hybrid nanoparticles into cancer cells. Nanomedicine 2025, 70, 102872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, S.; Rogers, D.; Kobylynska, M.; Geraets, J.A.; Thaysen, K.; Egebjerg, J.M.; Brink, M.C.; Herbsleb, L.; Salakova, M.; Fuchs, L.; et al. Demonstrating soft X-ray tomography in the lab for correlative cryogenic biological imaging using X-rays and light microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 45491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokke Rudraiah, P.; Herbsleb, L.; Salakova, M.; Gröger, H.; Steyer, A.M.; Alves, F.; Feldmann, C.; Walter, A. Combining Correlative Cryogenic Fluorescence and Electron Microscopy and Correlative Cryogenic Super-Resolution Fluorescence and X-Ray Tomography-Novel Complementary 3D Cryo-Microscopy Across Scales to Reveal Nanoparticle Internalization Into Cancer Cells. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2025, 89, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneckenburger, H.; Wagner, M.; Kretzschmar, M.; Strauss, W.S.L.; Sailer, R. Laser-assisted fluorescence microscopy for measuring cell membrane dynamics. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2004, 3, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhling, K.; French, P.M.; Phillips, D. Time-resolved fluorescence microscopy. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2005, 4, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, W. Fluorescence lifetime imaging--techniques and applications. J. Microsc. 2012, 247, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thermo Fisher Scientific. Spectraviewer. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/order/fluorescence-spectraviewer/?SID=srch-svtool&UID=7525moh#!/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Förster, T. Zwischenmolekulare Energiewanderung und Fluoreszenz. Ann. Phys. 1948, 437, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, B.R. Paths to Förster’s resonance energy transfer (FRET) theory. Eur. Phys. J. H 2014, 39, 87–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneckenburger, H. Förster resonance energy transfer—What can we learn and how can we use it? Methods Appl. Fluoresc. 2019, 8, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, D.W. A note on preliminary tests of equality of variances. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2004, 57, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutros, M.; Heigwer, F.; Laufer, C. Microscopy-Based High-Content Screening. Cell 2015, 163, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xia, M. Review of high-content screening applications in toxicology. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 3387–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadlbauer, V.; Lanzerstorfer, P.; Neuhauser, C.; Weber, F.; Stübl, F.; Weber, P.; Wagner, M.; Plochberger, B.; Wieser, S.; Schneckenburger, H.; et al. Fluorescence microscopy-based quantitation of GLUT4 translocation: High-throughput or high-content? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, V.; Lanzerstorfer, P.; Weghuber, J.; Schneckenburger, H. Super-Resolution Live Cell Microscopy of Membrane-Proximal Fluorophores. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, J.J.A.; Mostaço-Guidolin, L.B. Optical Microscopy and the Extracellular Matrix Structure: A Review. Cells 2021, 10, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cainero, I.; Cerutti, E.; Faretta, M.; Dellino, G.I.; Pelicci, P.G.; Bianchini, P.; Vicidomini, G.; Diaspro, A.; Lanzanò, L. Chromatin investigation in the nucleus using a phasor approach to structured illumination microscopy. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 2566–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleksiievets, N.; Thiele, J.C.; Weber, A.; Gregor, I.; Nevskyi, O.; Isbaner, S.; Tsukanov, R.; Enderlein, J. Wide-Field Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging of Single Molecules. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 3494–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, J.C.; Helmerich, D.A.; Oleksiievets, N.; Tsukanov, R.; Butkevich, E.; Sauer, M.; Nevskyi, O.; Enderlein, J. Confocal Fluorescence-Lifetime Single-Molecule Localization Microscopy. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 14190–14200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, L.A.; Dunlap, M.K.; Ryan, D.P.; Werner, J.H.; Goodwin, P.M.; Green, C.M.; Díaz, S.A.; Medintz, I.L.; Susumu, K.; Stewart, M.H.; et al. Super-Resolved Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging of Single Cy3 Molecules and Quantum Dots Using Time-Correlated Single Photon Counting with a Four-Pixel Fiber Optic Array Camera. J. Phys. Chem. A 2025, 129, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masullo, L.A.; Steiner, F.; Zähringer, J.; Lopez, L.F.; Bohlen, J.; Richter, L.; Cole, F.; Tinnefeld, P.; Stefani, F.D. Pulsed Interleaved MINFLUX. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radmacher, N.; Chizhik, A.I.; Nevskyi, O.; Gallea, J.I.; Gregor, I.; Enderlein, J. Molecular Level Super-Resolution Fluorescence Imaging. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2025, 54, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneckenburger, H.; Cremer, C. Keeping cells alive in microscopy. Biophysica 2025, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, D. Cell-substrate contacts illuminated by total internal reflection fluorescence. J. Cell Biol. 1981, 89, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, J.S.; Truskey, G.A.; Reichert, W.M. Quantitative analysis of variable-angle total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (VA-TIRFM) of cell/substrate contacts. J. Microsc. 1994, 173, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Weber, P.; Baumann, H.; Schneckenburger, H. Nanotopology of cell adhesion upon Variable-Angle Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence Microscopy (VA-TIRFM). J. Vis. Exp. 2012, 68, e4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddie, C.J.; Genoud, C.; Kreshuk, A.; Meechan, K.; Micheva, K.D.; Narayan, K.; Pape, C.; Parton, R.G.; Schieber, N.L.; Schwab, Y.; et al. Volume electron microscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2022, 2, 51, Correction in Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2022, 2, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Section | Sample | Fluorescence Decay Kinetics | Fluorescence Spectra | LSM Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1 | H8N8 | 3 exponential components (Figure 3) | Autofluorescence + IOH-NPs (Figure 2) | Ref. [5] |

| 2 h | τ2 = (1.70 ± 0.10) ns (λex = 550/610 nm) | IOH-NP band at 670/680 nm | I555 nm ≤ I639 nm | |

| 24 h | τ2 = (1.40 ± 0.24) ns (λex = 550/610 nm) Hypothesis: Shortening after cellular/lysosomal uptake | IOH-NP band increasing | I555 nm ≤ I639 nm (Figure 4) | |

| Medium 0 h | τ2 = (1.68 ± 0.08) ns (λex = 550/610 nm) | IOH-NP band at 670/680 nm | ||

| 24 h | τ2 = (1.47 ± 0.14) ns (λex = 550/610 nm) Hypothesis: Minor intrinsic change in fluorescence lifetime | IOH-NP band at 670/680 nm | ||

| Buffer pH 7.0 | τ2 = (1.80 ± 0.29) ns (median) τ2 = (2.667 ± 1.517) ns (mean value) | IOH-NP band at 670/680 nm | ||

| pH 4.0 | τ2 = (1.81 ± 0.26) ns (median) τ2 = (1.885 ± 0.466) ns (mean value) Mean values indicate shortening of τ2 with decreasing pH. | IOH-NP band at 670/680 nm; No spectral shift with pH | ||

| 2.2 | H8N8 | τeff = 2.5–3.5 ns all over the cells (FLIM); (λex = 610 nm) (Supplementary Figure S1) | ||

| 2.3 | LysoTr. | τ1 = 0.5–0.7 ns τ2 = (4.36 ± 0.20) ns (λex = 470 nm) | Broad spectral band with maximum at 530–535 nm and long-wave tail up to 730 nm | |

| LysoTr. + IOH-NPs | τ1 = 0.5–0.7 ns τ2 = (4.05 ± 0.30) ns (λex = 470 nm), Shortening explained by FRET LysoTracker ⟶ IOH-NPs | I555 nm ≥ I639 nm indicating additional excitation via FRET (Figure 4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Eckstein, S.; Herbsleb, L.; Gröger, H.; Feldmann, C.; Alves, F.; Walter, A.; Schneckenburger, H. Monitoring Nanoparticle Interaction with Murine Breast Cancer Cells Using Multimodal Fluorescence Lifetime Microscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031339

Eckstein S, Herbsleb L, Gröger H, Feldmann C, Alves F, Walter A, Schneckenburger H. Monitoring Nanoparticle Interaction with Murine Breast Cancer Cells Using Multimodal Fluorescence Lifetime Microscopy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031339

Chicago/Turabian StyleEckstein, Steven, Louisa Herbsleb, Henriette Gröger, Claus Feldmann, Frauke Alves, Andreas Walter, and Herbert Schneckenburger. 2026. "Monitoring Nanoparticle Interaction with Murine Breast Cancer Cells Using Multimodal Fluorescence Lifetime Microscopy" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031339

APA StyleEckstein, S., Herbsleb, L., Gröger, H., Feldmann, C., Alves, F., Walter, A., & Schneckenburger, H. (2026). Monitoring Nanoparticle Interaction with Murine Breast Cancer Cells Using Multimodal Fluorescence Lifetime Microscopy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1339. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031339