Sub-Internal Limiting Membrane Hemorrhage: Molecular Microenvironment and Review of Treatment Modalities

Abstract

1. Introduction

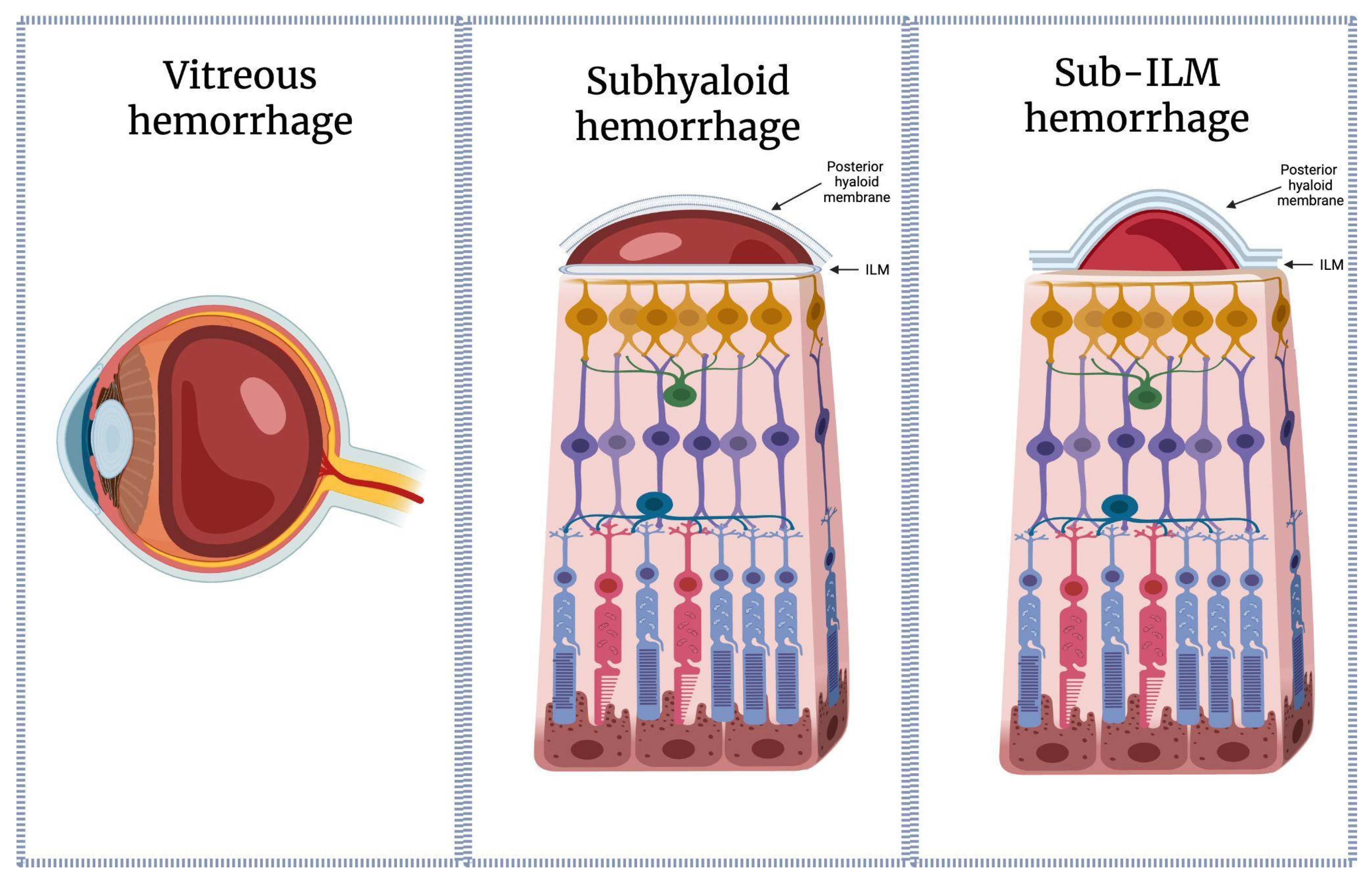

1.1. Definition and Clinical Importance of Sub-ILM Hemorrhage

1.2. Distinction Between Sub-ILM, Subhyaloid, and Intravitreal Hemorrhages

1.3. Rationale for Focusing on Molecular and Microenvironmental Aspects

1.4. Scope and Structure of the Review

2. Anatomy and Molecular Structure of the Internal Limiting Membrane

2.1. Structural Components (Collagen IV, Laminins, Nidogens, Proteoglycans)

2.2. Barrier Properties and Permeability Characteristics

2.3. ILM–Müller Cell Interface

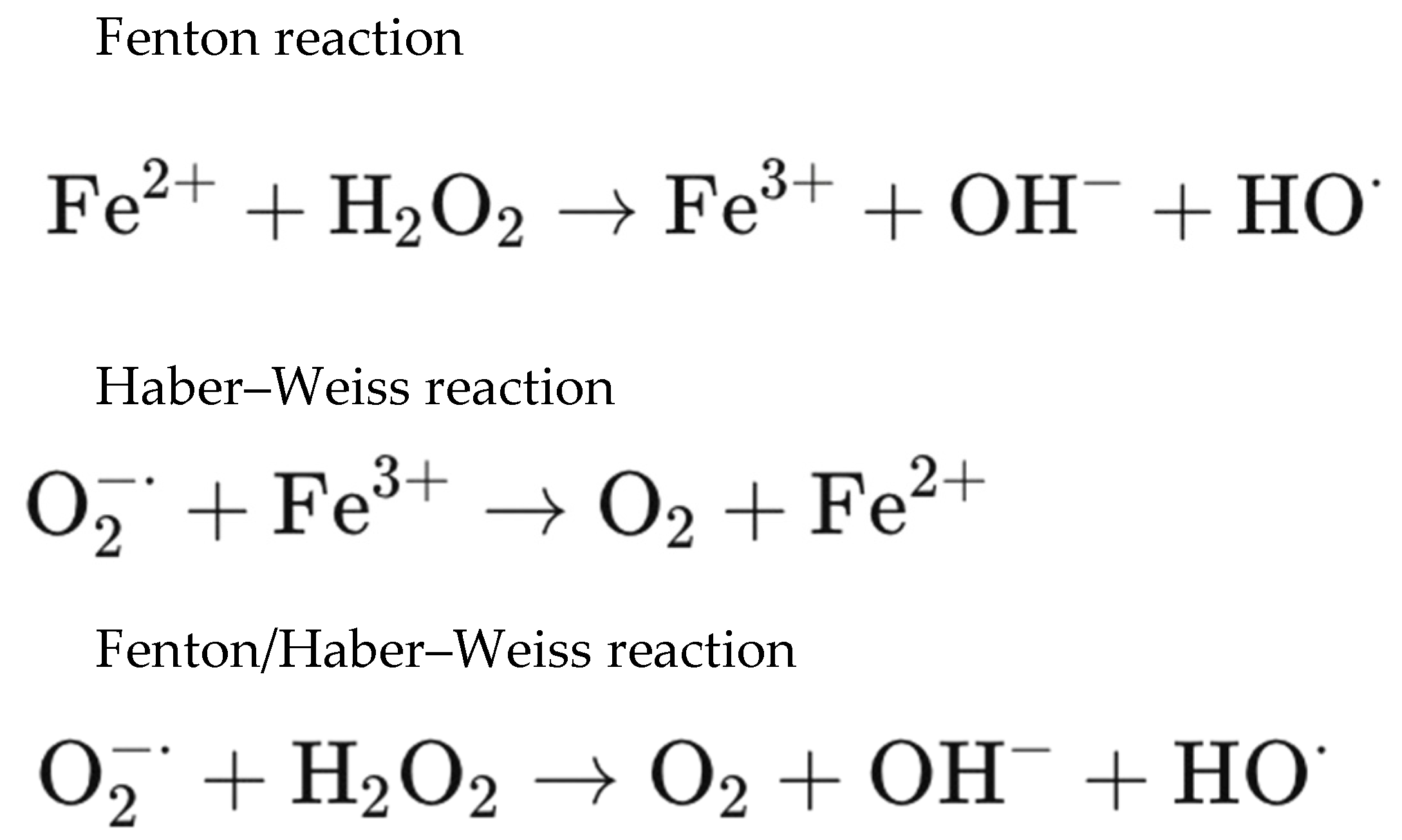

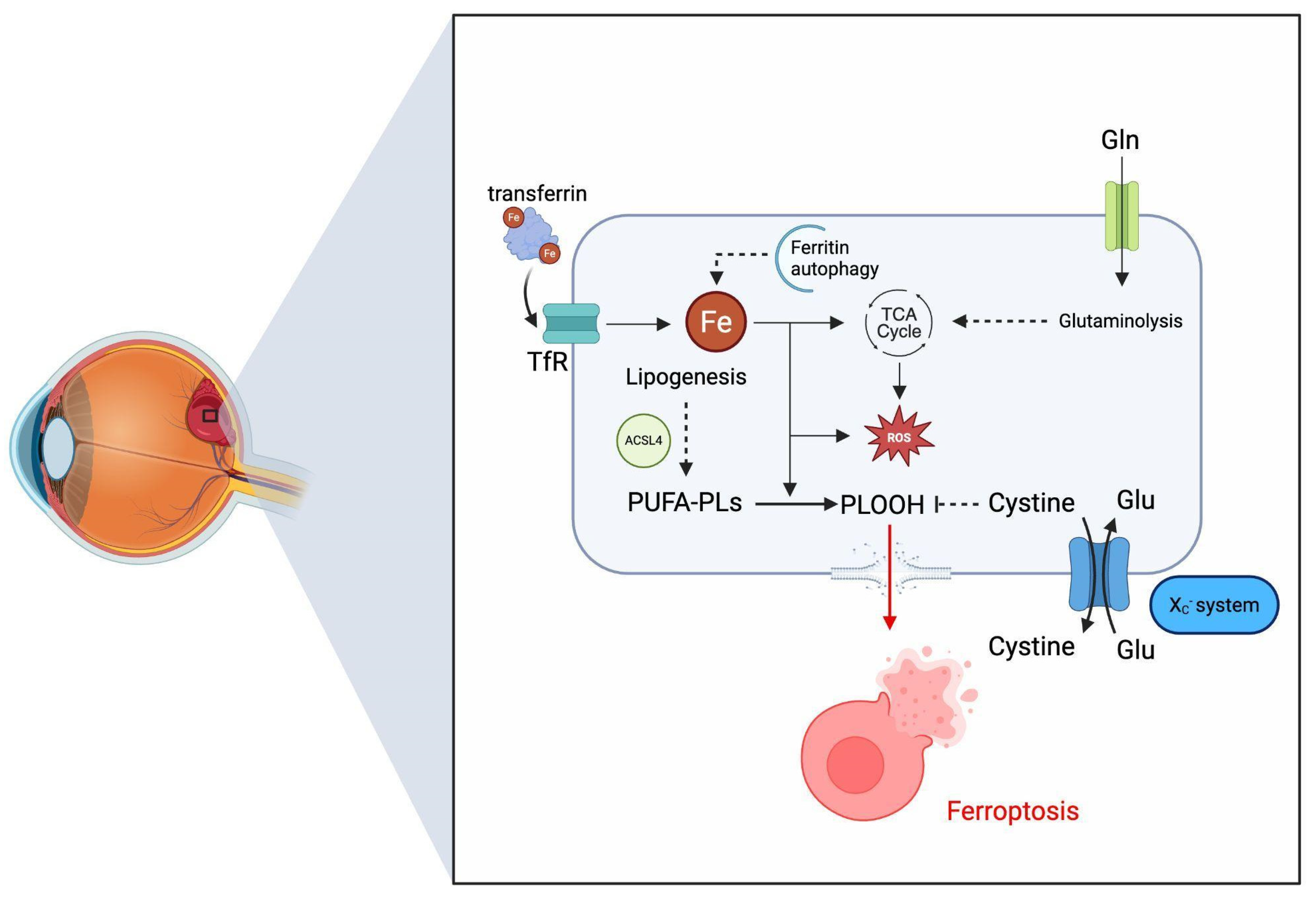

3. Molecular Microenvironment of Blood Entrapment Under the ILM

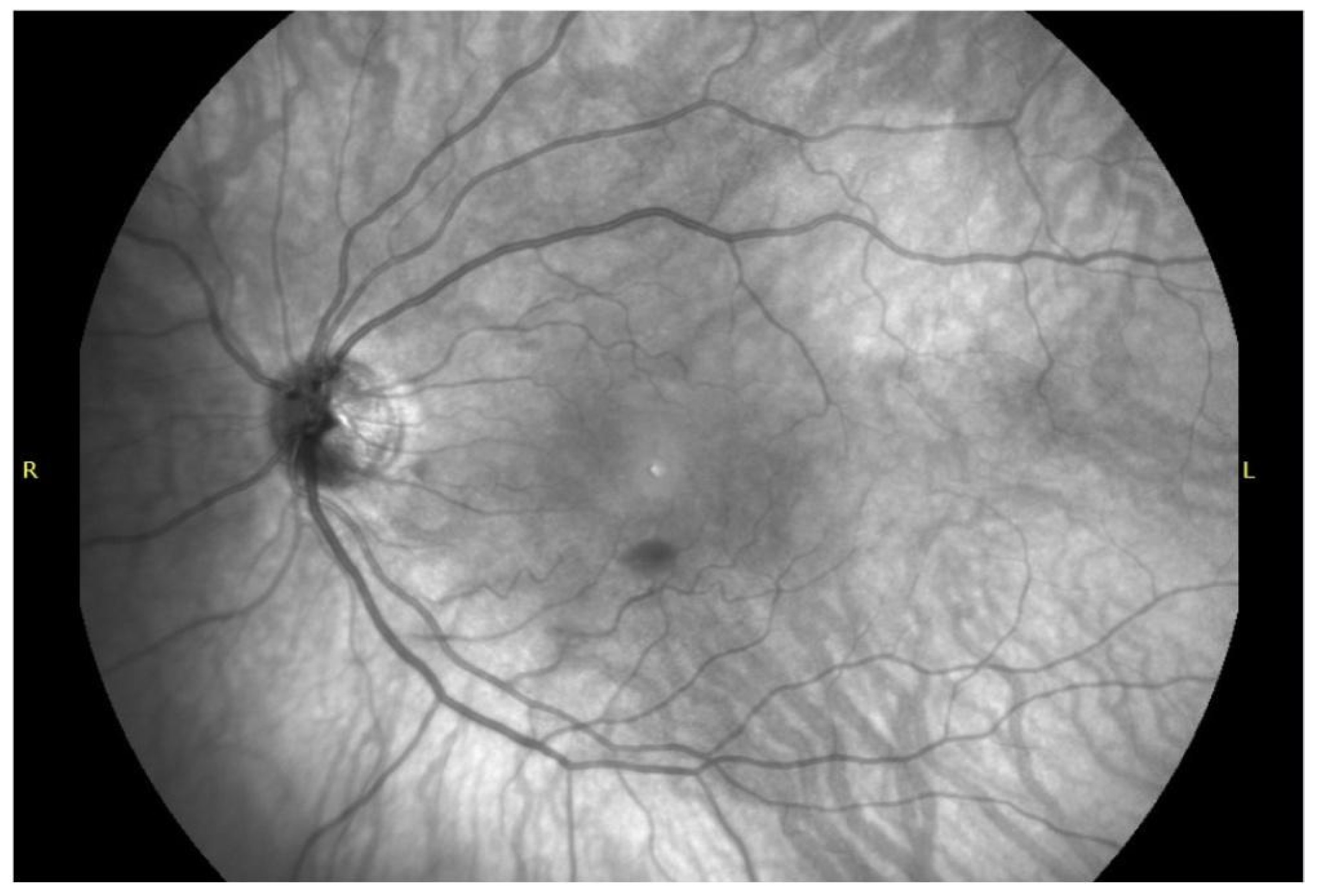

4. Diagnostic Features and Imaging Biomarkers

4.1. Sub-ILM Hemorrhage SD-OCT Imaging Characteristics

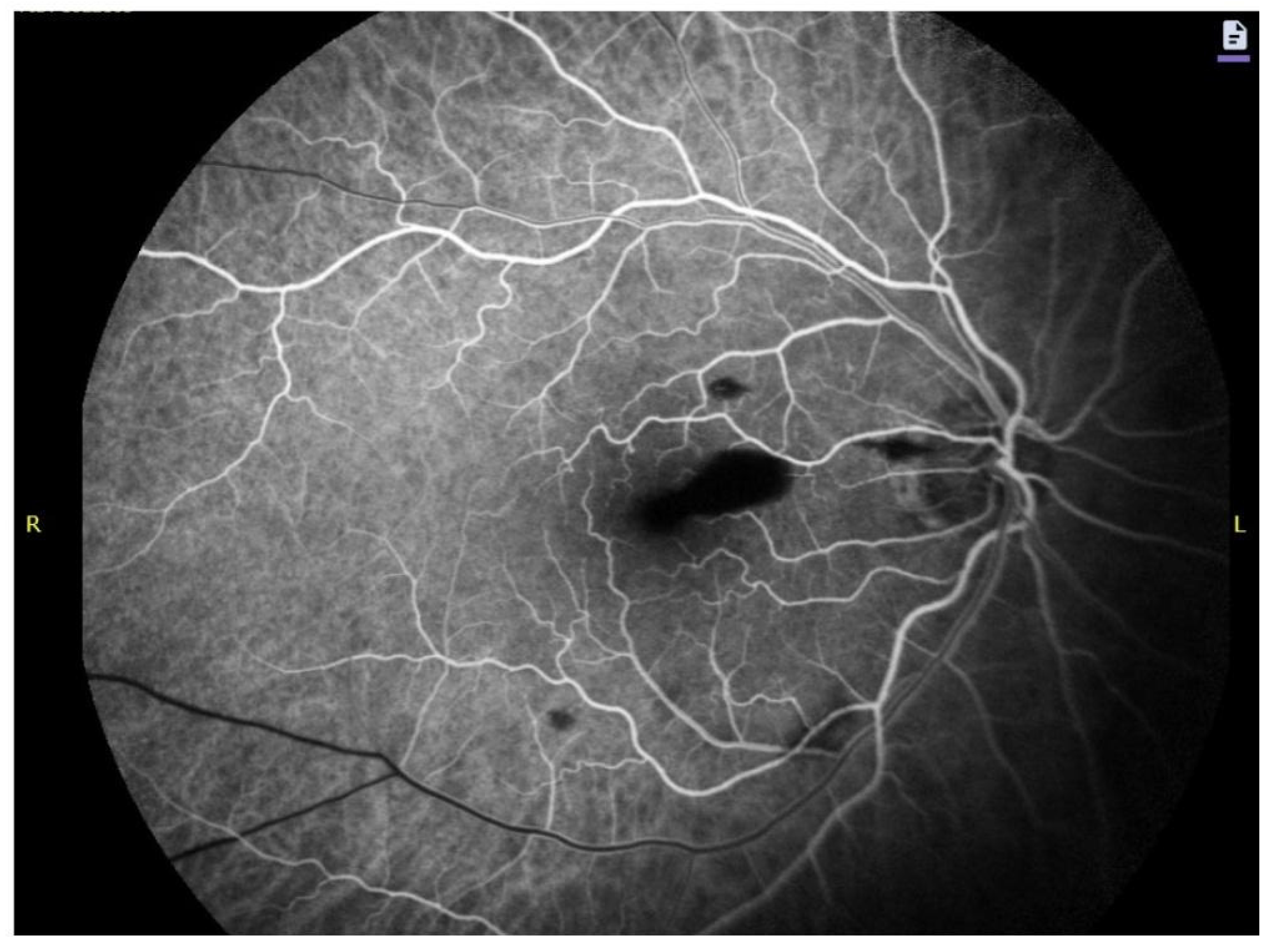

4.2. Autofluorescence, Fluorescein Angiography and Near-Infrared Signatures

4.3. Imaging Biomarkers of Hemoglobin Breakdown and Chronology

5. Review of Available Treatment Modalities

5.1. Molecular Rationale for Early vs. Delayed Intervention

5.2. Immediate Intervention Overview: ILM Puncture, Pneumatic Displacement, or Vitrectomy

5.3. Potential for Preventing Inner-Retinal Toxicity

6. Future Directions

6.1. Gaps in Understanding Sub-ILM Biochemical Dynamics

6.2. Need for Molecular Biomarkers and Imaging Correlates

6.3. Research Priorities for Optimizing Treatment Timing

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Autofluorescence |

| cGMP | Cyclic Guanosine Monophosphate |

| EAAT | Excitatory Amino Acid Transporter |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ILM | Internal limiting membrane |

| Nd: YAG | Neodymium: yttrium–aluminum–garnet laser |

| NIR | Near-infrared reflectance |

| NFL | Nerve fiber layer |

| SD-OCT | Spectral domain optical coherence tomography |

| PPV | Pars plana vitrectomy |

| PVD | Posterior vitreous detachment |

| PVR | Proliferative vitreoretinopathy |

| RAM | Retinal arterial macroaneurysm |

| RD | Retinal detachment |

| RGC | Retinal ganglion cell |

| RNFL | Retinal nerve fiber layer |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SAH | Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| tPA | Tissue Plasminogen Activator |

| VA | Visual acuity |

| VH | Vitreous hemorrhage |

References

- Brar, A.S.; Ramachandran, S.; Takkar, B.; Narayanan, R.; Mandal, S.; Padhy, S.K. Characterization of retinal hemorrhages delimited by the internal limiting membrane. Indian. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 72, S3–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazar, Z.; Şevik, Ö.; Gürsel, E. Valsalva Retinopathy (Valsalva Retinopatisi). J. Retin.-Vitr. 2005, 13, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, J.; Eagle, R.; Levin, A. Peripheral hemorrhagic detachment of the internal limiting membrane in abusive head trauma. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 6177. [Google Scholar]

- Mennel, S. Subhyaloidal and macular haemorrhage: Localisation and treatment strategies. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 850–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwase, T.; Ra, E.; Ito, Y.; Terasaki, H. Multiple sub–internal limiting membrane hemorrhages with double ring sign in eyes with Valsalva retinopathy. Retina 2018, 38, e1–e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.N.; Stappler, T.; Hiscott, P.; Wong, D. Histopathological changes and clinical outcomes following intervention for sub-internal limiting membrane haemorrhage. Ophthalmologica 2020, 243, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotani, Y.; Imai, H.; Kishi, M.; Yamada, H.; Matsumiya, W.; Miki, A.; Kusuhara, S.; Nakamura, M. Removal of sub-internal limiting membrane hemorrhage secondary to Valsalva retinopathy using a fovea-sparing internal limiting membrane fissure creation technique. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. Med. 2024, 2774155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.S.; Walter, S.D.; Fekrat, S. Bilateral prefoveal sub-internal limiting membrane hemorrhage in autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Ophthalmic Surg. Lasers Imaging Retin. 2016, 47, 1151–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, Y.; Shimada, H.; Kawamura, A.; Kaneko, H.; Tanaka, K.; Nakashizuka, H. Differentiation of premacular hemorrhages with niveau formation. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 15, 2037–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Y.; Johnson, T.V. The internal limiting membrane: Roles in retinal development and implications for emerging ocular therapies. Exp. Eye Res. 2021, 206, 108545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramov, A.Y.; Scorziello, A.; Duchen, M.R. Three distinct mechanisms generate oxygen free radicals in neurons and contribute to cell death during anoxia and reoxygenation. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beebe, D.C.; Shui, Y.-B.; Siegfried, C.J.; Holekamp, N.M.; Bai, F. Preserve the (intraocular) environment: The importance of maintaining normal oxygen gradients in the eye. Jpn. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 58, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filas, B.A.; Shui, Y.-B.; Beebe, D.C. Computational model for oxygen transport and consumption in human vitreous. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 6549–6559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Vishwanath, S.; Azad, S.V.; Aggarwal, V. Intraoperative optical coherence tomography–guided identification of resolved sub-internal limiting membrane hemorrhage in leukemic retinopathy. Indian J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2021, 1, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manayath, G.J.; Verghese, S.; Ranjan, R.; Narendran, V. Sub-internal limiting membrane hemorrhage as an unusual presentation of polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy. Oman J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 14, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giblin, F.J.; Quiram, P.A.; Leverenz, V.R.; Baker, R.M.; Dang, L.; Trese, M.T. Enzyme-induced posterior vitreous detachment in the rat produces increased lens nuclear pO2 levels. Exp. Eye Res. 2009, 88, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xiao, C.; Tao, H.; Tang, X. Research progress of iron metabolism in retinal diseases. Adv. Ophthalmol. Pract. Res. 2023, 3, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseyev, G.; Takahashi, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gentleman, S.; Redmond, T.M.; Crouch, R.K.; Ma, J.X. RPE65 Is an Iron(II)-dependent Isomerohydrolase in the Retinoid Visual Cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 2835–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yefimova, M.G.; Jeanny, J.-C.; Guillonneau, X.; Keller, N.; Nguyen–Legros, J.; Sergeant, C.; Guillou, F.; Courtois, Y. Iron, Ferritin, Transferrin, and Transferrin Receptor in the Adult Rat Retina. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000, 41, 2343–2351. [Google Scholar]

- Yefimova, M.G.; Jeanny, J.-C.; Keller, N.; Sergeant, C.; Guillonneau, X.; Beaumont, C.; Courtois, Y. Impaired Retinal Iron Homeostasis Associated with Defective Phagocytosis in Royal College of Surgeons Rats. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2002, 43, 537–545. [Google Scholar]

- Shahandeh, A.; Bui, B.V.; Finkelstein, D.I.; Nguyen, C.T.O. Effects of Excess Iron on the Retina: Insights From Clinical Cases and Animal Models of Iron Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 794809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hahn, P.; Iacovelli, J.; Wong, R.; King, C.; Bhisitkul, R.; Massaro-Giordano, M.; Dunaief, J.L. Iron homeostasis and toxicity in retinal degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2007, 26, 649–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, E.; Daruich, A.; Youale, J.; Courtois, Y.; Behar-Cohen, F. From Rust to Quantum Biology: The Role of Iron in Retina Physiopathology. Cells 2020, 9, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guajardo, M.H.; Terrasa, A.M.; Catalá, A. Lipid-protein modifications during ascorbate-Fe2+ peroxidation of photoreceptor membranes: Protective effect of melatonin. J. Pineal Res. 2006, 41, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akeo, K.; Hiramitsu, T.; Yorifuji, H.; Okisaka, S. Membranes of Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells In Vitro are Damaged in the Phagocytotic Process of the Photoreceptor Outer Segment Discs Peroxidized by Ferrous Ions. Pigment. Cell Res. 2002, 15, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, K.; Kim, H.J.; Zhao, J.; Song, Y.; Dunaief, J.L.; Sparrow, J.R. Iron promotes oxidative cell death caused by bisretinoids of retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4963–4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zastawny, T.H.; Altman, S.A.; Randers-Eichhorn, L.; Madurawe, R.; Lumpkin, J.A.; Dizdaroglu, M.; Rao, G. DNA base modifications and membrane damage in cultured mammalian cells treated with iron ions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995, 18, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Lukas, T.J.; Du, N.; Suyeoka, G.; Neufeld, A.H. Dysfunction of the retinal pigment epithelium with age: Increased iron decreases phagocytosis and lysosomal activity. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 1895–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Li, S.; Wu, H.; Wei, D.; Pu, N.; Wang, K.; Liu, Y.; Tao, Y.; Song, Z. Ferroptosis: An Energetic Villain of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.-G.; Yu, S.-Q.; Chen, X.; Zhu, J.; Chen, F. Macular hole secondary to Valsalva retinopathy after doing push-up exercise. BMC Ophthalmol. 2014, 14, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibran, S.K.; Kenawy, N.; Wong, D.; Hiscott, P. Changes in the retinal inner limiting membrane associated with Valsalva retinopathy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 701–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodake, A.; Das, D.; Bhattacharjee, H.; Barman, M.J.; Magdalene, D.; Ghosh, R.; Mishra, S. Bilateral sub-internal limiting membrane hemorrhage in a COVID-19 patient. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 70, 3141–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Goel, N. “Arcus retinalis”: A novel clinical marker of sub-internal limiting membrane hemorrhage. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 31, 1986–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conci, L.; Pereira, E.; Navajas, S.; Silva Neto, E.; Pimentel, S.; Zacharias, L. Valsalva retinopathy presenting as subretinal hemorrhage. Case Rep. Ophthalmol. Med. 2024, 2024, 4865222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayamizu, R.; Totsuka, K.; Azuma, K.; Sugimoto, K.; Toyama, T.; Araki, F.; Shiraya, T.; Ueta, T. Optical coherence tomography findings after surgery for sub-inner limiting membrane hemorrhage due to ruptured retinal arterial macroaneurysm. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.C.F.; Miranda, R.S.; Zacharias, L.C.; Monteiro, M.L.R.; Takahashi, W.Y. Novel outer retinal optical coherence tomography hyperreflective abnormality associated with sub–internal limiting membrane hemorrhage. Retina 2015, 35, 1713–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, S.; Fukuyama, H.; Araki, T.; Kimura, N.; Gomi, F. Sub–internal limiting membrane foveal hemorrhage under tension: Optical coherence tomography biomarkers predicting macular hole formation after submacular hemorrhage. Retina 2025, 45, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.-Y.; Wang, J.-K.; Yang, C.-H. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography findings of subinternal limiting membrane hemorrhage in the macula before and after Nd:YAG laser treatment. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 5, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumdar, A.; Balaji, A.; Shaikh, N.F. Persistent pre-macular cavity post-laser membranotomy for Valsalva retinopathy. Indian J. Ophthalmol. Case Rep. 2025, 5, 368–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, P.K.; Mohanty, L.; Thareja, J. Resolving sub-internal limiting membrane haemorrhage mimicking as endogenous endophthalmitis. J. Clin. Sci. Res. 2024, 13, S22–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Fernández, M.; Navarro, J.C.; Castaño, C.G. Long-term evolution of Valsalva retinopathy: A case series. J. Med. Case Rep. 2012, 6, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, O.S.; Alsulami, R.E.; Alqahtani, B.S.; Alqahtani, A. Spontaneous Resolution of Foveal Sub-internal Limiting Membrane Hemorrhage with Excellent Visual and Anatomical Outcome in a Patient with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Middle East Afr. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 27, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováčová, M.; Kousal, B.; Meliška, M.; Fichtl, M.; Dušková, J.; Kalvodová, B. Treatment options for premacular and sub-internal limiting membrane hemorrhage. Česka A Slov. Oftalmol. 2021, 77, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, J.S.; Seo, Y.; Koh, H.J.; Lee, S.C. YAG laser membranotomy for sub-internal limiting membrane hemorrhage. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2015, 92, e154–e157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, D.; Bhandari, S.; Bajimaya, S.; Thapa, R.; Paudyal, G.; Pradhan, E. Nd: YAG laser hyaloidotomy in the management of premacular subhyaloid hemorrhage. BMC Ophthalmol. 2016, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Han, G.H.; Chung, Y.R. Traumatic subhyaloid hemorrhage treated with argon laser-assisted hyaloidotomy. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 18, 562–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Cao, X.; Zhou, H.; Jia, L.; Gao, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; She, H.; Ma, K.; et al. Efficiency and complication of 577-nm laser membranotomy for the treatment of retinal sub-inner limiting membrane hemorrhage. Front. Ophthalmol. 2022, 2, 935188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, Y.K.; Huang, Y.M.; Lin, P.K. Sub-internal limiting membrane hemorrhage treated with intravitreal tissue plasminogen activator followed by octafluoropropane gas injection. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 5, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jilani, T.N.; Siddiqui, A.H. Tissue Plasminogen Activator. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Xuan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Xu, G. Bilateral macular holes and a new onset vitelliform lesion in Best disease. Ophthalmic Genet. 2017, 38, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, H.; Guo, H.; Han, H.; Zhou, F.; Wang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yan, H. Vitrectomy combined with internal limiting membrane peeling for the treatment of hemorrhagic retinal arterial macroaneurysm with “multilayered” hemorrhages. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2025, 40, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tian, B.; Wei, W. Timely vitrectomy and inner limiting membrane peeling is effective and safe for Terson syndrome with vitreous hemorrhage and sub–inner limiting membrane hemorrhage. Asia-Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 11, 392–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Maeyer, K.; Van Ginderdeuren, R.; Postelmans, L.; Stalmans, P.; Van Calster, J. Sub-inner limiting membrane haemorrhage: Causes and treatment with vitrectomy. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 869–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, F.; Morris, R.; Witherspoon, C.D.; Mester, V. Terson syndrome: Results of vitrectomy and the significance of vitreous hemorrhage in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ophthalmology 1998, 105, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, A.; Imai, H.; Iwane, Y.; Kishimoto, M.; Sotani, Y.; Yamada, H.; Matsumiya, W.; Miki, A.; Kusuhara, S.; Nakamura, M. Removal of Sub-Internal Limiting Membrane Hemorrhage Secondary to Retinal Arterial Macroaneurysm Rupture: Internal Limiting Membrane Non-Peeling Technique. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, W.; Kim, W.; Lee, S. Comparison of fovea-sparing (button-hole) and conventional internal limiting membrane peeling in retinal arterial macroaneurysm rupture: Visual and anatomical outcomes. Retina 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, N.; Kohli, P.; Rajan, R.P.; Ramasamy, K. Inverse drainage Nd: YAG membranotomy for pre-macular hemorrhage. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 33, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.C.; Hsieh, Y.T.; Yang, C.M.; Berrocal, M.H.; Dhawahir-Scala, F.; Ruamviboonsuk, P.; Pappuru, R.R.; Dave, V.P. Vitrectomy for diabetic retinopathy: A review of indications, techniques, outcomes, and complications. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 14, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stappler, T.; Hussain, R.; Pappas, G.; Hiscott, P.; Wong, D. Sub-internal limiting membrane haemorrhage: A clinico-pathological study to guide the timing of surgical intervention. ARVO Annual Meeting Abstracts. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 5258. [Google Scholar]

- An, J.H.; Jang, J.H. Macular hole formation following vitrectomy for ruptured retinal arterial macroaneurysm. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 35, 248–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Etiology | Estimated Frequency (% of Reported Sub-ILM Cases) | Pathophysiological Mechanism | Typical Patient Profile | Clinical Features | Prognostic Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valsalva retinopathy | 35–45% | Sudden venous pressure rise, leading to a rupture of a superficial retinal vessel beneath ILM. | Usually overall healthy young adults with a history of heavy lifting/coughing/vomiting. | Sudden painless central scotoma; usually unilateral. | Excellent prognosis with decompression; Nd: YAG or PPV effective if dense. |

| Retinal arterial macroaneurysm (RAM) rupture | 20–30% | Rupture of arterial macroaneurysm causing hemorrhage including sub-ILM. | Older hypertensive patients. | Acute unilateral vision loss; may show multilayer hemorrhage. | ILM-sparing PPV may preserve fovea; prognosis depends on hemorrhage layers. |

| Terson syndrome | 10–15% | Acute intracranial pressure surge, causing cranial venous congestion, resulting in retinal vessel rupture under ILM. | Patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) or severe head trauma; occurs often bilaterally. | Severe vision loss; often with associated vitreous hemorrhage. | More persistent hemorrhage; PPV commonly indicated. |

| Ocular trauma | 10–20% | Blunt trauma, leading to shearing of the ILM and vessel rupture. | Often younger individuals; sports or accidents. | Acute visual acuity (VA) drop with coexisting traumatic signs. | Elevated risk of macular hole formation; PPV often required. |

| Blood dyscrasias (leukemia, anemia, thrombocytopenia) | 3–8% | Vessel fragility or coagulopathy. | Patients with systemic hematologic disease. | Variable presentation; may be bilateral. | Management influenced by the degree of systemic stability. |

| Fragile neovascularization, e.g., proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) | 5–10% | Rupture of neovascular fronds. | Diabetic or ischemic retinopathy patients. | Acute/subacute VA loss; bleeding often multilayered. | Requires control of underlying neovascular disease; PPV if dense. |

| Idiopathic cases | <3% | Spontaneous microvascular rupture without clear underlying cause. | Any age; no systemic association. | Mild to moderate VA decline. | Often small and self-limiting. |

| Hemorrhage Stage | Time Window | OCT Biomarkers | Biochemical State | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh hemorrhage | 0–3 days | Smooth dome-shaped ILM elevation; homogeneous hyperreflective blood; intact ILM line. | Intact erythrocytes; oxyhemoglobin predominates; minimal iron release or reactive oxygen species (ROS) creation. | Best timing for Nd: YAG membranotomy with rapid visual recovery expected. |

| Early lysis phase | 3–14 days | Increasing signal granularity; early internal heterogeneity or layering. | Hemoglobin oxidation to methemoglobin; onset of iron release; early ROS generation. | Toxicity begins to rise; pneumatic displacement ± tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) administration still feasible. |

| Oxidative/toxic phase | 2–6+ weeks | Markedly heterogeneous or clotted appearance; persistent ILM elevation. | High Fe2+ load; Fenton reaction with ROS; marked Müller and retinal ganglion cell (RGC) oxidative stress. | Significant risk of inner retinal injury; PPV with ILM peeling increasingly favored. |

| Fibrotic/late stage | >6 weeks | Irregular ILM contour; tractional changes; organized clot. | Macrophage, fibroblast, and RPE-like cell proliferation; chronic degradation products present. | Lower visual prognosis; PPV often required; risk of PVR-like sequelae formation. |

| Treatment Modality | Mechanism of Action | Ideal Indications | Contraindications/Limitations | Typical Clearance Time | Expected Visual Outcome | Advantages | Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | Slow spontaneous erythrocyte lysis and absorption without any iatrogenic intervention. | Small, extrafoveal hemorrhages with minimal visual impairment in medically fragile patients (e.g., leukemia). | Very slow clearance; prolonged exposure to iron/ROS-related retinal damage; increased risk of PVR-like changes. | Weeks–months. | Lowest mean VA improvement. | Non-invasive; no procedural risks. | Higher retinal toxicity risk; poor outcomes in dense or foveal hemorrhage. |

| Nd: YAG membranotomy | Creates focal ILM perforation which decompresses the sub-ILM compartment; blood drains into the vitreous. | Fresh (<1–2 weeks), non-clotted foveal hemorrhage with good posterior vitreous visualization. | Clotted or organized blood; very thick ILM; risk of off-target retinal impact. | Hours–days. | Rapid VA improvement. | Minimally invasive; immediate decompression. | Potential ILM/retinal injury; incomplete drainage; persistent premacular cavity possible. |

| Pneumatic displacement (±tPA) | Intravitreal gas shifts blood away from fovea; tPA dissolves clot when present. | Recent hemorrhage; moderately dense collections in patients with ability to hold posture. | Thick, chronic, highly organized clot (if no tPA); limited by need for patient positioning. | Days to 1–2 weeks. | Good VA recovery when performed early. | Minimally invasive; avoids vitrectomy; tPA effective for semi-clotted blood. | Gas-related complications; inconsistent efficacy; patient-dependent posturing adherence affecting outcome. |

| PPV without ILM peeling | Vitrectomy with mechanical evacuation of sub-ILM blood via incision/aspiration while preserving ILM. | Cases where ILM preservation is desirable, e.g., thin fovea, high macular hole (MH); some retinal arterial macroaneurysm (RAM) ruptures. | Residual blood/toxic products may remain; less complete decompression than ILM peel. | Immediate. | Good VA improvement; inferior to peeling in chronic or dense cases. | Protects native ILM; reduces risk of peeling-related trauma. | Persistent dome, incomplete clearance, possible need for secondary surgery. |

| PPV with buttonhole (fovea-sparing) ILM peeling | Selective ILM opening with “buttonhole” sparing of the foveal ILM while removing adjacent ILM to release hemorrhage. | RAM rupture; cases where preserving foveal ILM architecture is critical. | Technically demanding; not ideal for chronic or multilayer hemorrhage. | Immediate. | Reported to yield better foveal structural and visual outcomes than full peeling. | Decompresses hemorrhage while sparing fovea; reduces risk of iatrogenic MH. | Requires surgical expertise; may not fully clear toxic compartment if bleeding is chronic. |

| PPV with conventional ILM peeling | Complete removal of ILM and evacuation of the blood; completely eliminates confined compartment and toxic breakdown products. | Dense or long-standing, clotted macular hemorrhage; chronic or recuring cases; multilayer hemorrhages; Terson syndrome. | Surgical risks; not preferred when foveal ILM preservation is needed. | Immediate. | Highest and most reliable VA gains; most complete anatomic result. | Definitive clearance of iron/ROS burden; prevents PVR-like sequelae; effective regardless of chronicity. | Risk of retinal trauma, macular hole, retinal detachment (RD), cataract; most invasive option. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Eder, K.; Langosz, P.; Danikiewicz-Zagała, M.; Leszczyński, R.; Wyględowska-Promieńska, D. Sub-Internal Limiting Membrane Hemorrhage: Molecular Microenvironment and Review of Treatment Modalities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031336

Eder K, Langosz P, Danikiewicz-Zagała M, Leszczyński R, Wyględowska-Promieńska D. Sub-Internal Limiting Membrane Hemorrhage: Molecular Microenvironment and Review of Treatment Modalities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(3):1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031336

Chicago/Turabian StyleEder, Krzysztof, Paulina Langosz, Marta Danikiewicz-Zagała, Rafał Leszczyński, and Dorota Wyględowska-Promieńska. 2026. "Sub-Internal Limiting Membrane Hemorrhage: Molecular Microenvironment and Review of Treatment Modalities" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 3: 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031336

APA StyleEder, K., Langosz, P., Danikiewicz-Zagała, M., Leszczyński, R., & Wyględowska-Promieńska, D. (2026). Sub-Internal Limiting Membrane Hemorrhage: Molecular Microenvironment and Review of Treatment Modalities. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(3), 1336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27031336