1. Introduction

TIGIT (T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains) and its ligand CD155 (PVR) function as immune checkpoint molecules [

1]. TIGIT is an inhibitory receptor expressed on the surface of distinct immune cell subsets, mainly T cells, such as CD8

+, CD4

+, and regulatory T cells (Tregs), and also Natural Killer (NK) cells [

1,

2,

3]. TIGIT primarily interacts with four ligands, among which CD155 is considered the dominant binding partner [

4,

5]. CD155 is a nectin-like adhesion molecule, lowly expressed at endothelial, epithelial, and immune cells [

6,

7]. CD155 expression can be markedly increased in specific settings, including stimulation by inflammatory cytokines, cellular stress, heightened proliferative activity, and conditions present within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [

8,

9,

10]. Through multiple downstream mechanisms, the TIGIT/CD155 interaction suppresses the function of T cells and NK cells, thereby attenuating antitumor immunity and promoting tumor development and progression [

11,

12]. Accordingly, therapeutic blockade of the TIGIT/CD155 axis is being actively investigated to restore effective antitumor immunity, improve responses to existing immune checkpoint inhibitors, and increase the number of patients who benefit from immunotherapy [

13]. However, CD155 is not exclusively linked to the inhibitory TIGIT pathway. It also binds DNAM-1 (CD226), an activating receptor expressed on NK and T cells that promotes antitumor effector functions, as well as CD96 (TACTILE), which is commonly described as inhibitory but may exert activating or context-dependent effects in selected settings [

14,

15]. Collectively, signaling through the CD96/TIGIT/CD226 receptor axis reflects a dynamic balance between inhibitory and activating cues in NK and T cells, shaped by competing receptor–ligand interactions and reciprocal receptor cross-regulation within the TME [

16].

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is characterized by a complex pathogenic landscape, with diverse genetic alterations that differentially shape the TME, including the density and composition of tumor-infiltrating immune cell subsets, local cytokine and chemokine profiles, and the expression of immunoregulatory molecules [

17]. These molecular features, including mismatch repair (MMR) status,

RAS/BRAF mutations, and other defining alterations, strongly influence sensitivity to systemic therapies, particularly immunotherapy [

18,

19,

20]. In CRC, immune checkpoint blockade targeting PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 has demonstrated clinical efficacy mainly in tumors with high microsatellite instability and deficient mismatch repair (MSI-H/dMMR) [

21,

22]. However, MSI-H/dMMR tumors account for only approximately 10–15% of all CRC cases, and both primary and acquired resistance to checkpoint inhibition are common [

23,

24]. As a result, only a minority of patients currently gain durable benefit from approved immunotherapies. This gap underscores the need to broaden immunotherapeutic strategies beyond established checkpoints and to identify novel targets and combinations that can overcome therapeutic resistance [

24]. In this context, inhibitory pathways such as TIGIT/CD155 are of particular interest, as they may modulate responses to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade and provide additional opportunities to reinvigorate antitumor immunity. As clinical development of TIGIT/CD155-directed therapies progresses, a more precise understanding of how TIGIT and CD155 expression relates to clinically relevant mutations in CRC, including

KRAS,

NRAS,

BRAF, and

PIK3CA mutations, and to key features of the TME will be crucial for the implementation of personalized treatment strategies.

KRAS,

NRAS,

BRAF, and

PIK3CA mutations occur at different frequencies in CRC and exert distinct effects on tumor biology, including the composition and functional properties of the TME, particularly its immune component. Oncogenic mutations in

KRAS occur in ~35–45% of CRC cases, whereas

NRAS mutations are found in ~5–10% [

25,

26]. From a clinical perspective,

KRAS and

NRAS represent the most relevant members of the RAS family, which regulate key signaling cascades controlling cell proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, programmed cell death, and migration. Beyond their well-established oncogenic functions,

KRAS mutations can also reshape the immune TME, promoting an immunosuppressive TME through multiple mechanisms [

27,

28,

29].

BRAF mutations are present in about 10% of CRCs, more than 90% of which are accounted for by the

BRAF V600E variant.

BRAF-mutant CRCs frequently co-occur with MSI-H/dMMR status, increased expression of immune checkpoint-related genes, and an altered immune infiltrate characterized by higher densities of certain immune cell populations [

30,

31,

32,

33].

PIK3CA mutations occur in approximately 15–20% of CRC cases.

PIK3CA mutation or overexpression has been associated with resistance to immunotherapy [

34,

35]. Collectively,

KRAS,

NRAS,

BRAF, and

PIK3CA mutations, together with MSI status, differentially modulate intracellular signaling networks and the immunological and stromal composition of the TME, thereby influencing prognosis and shaping therapeutic opportunities. In line with this, the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology advise evaluating mutations in

KRAS,

NRAS, and

BRAF, as well as MSI status, to enable personalized therapy selection and improve patient stratification in CRC [

36].

Given the pivotal impact of these molecular alterations in defining the CRC immune landscape, it is likely that they also shape the activity of additional checkpoint axes beyond the canonical PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 pathways. In particular, the TIGIT/CD155 axis has gained attention as a critical regulator of T cell and NK cell function within the TME and as a promising target for next-generation immunotherapeutic approaches. The genomic background of CRC, including alterations in KRAS, NRAS, PIK3CA, AKT1, BRAF, and the tumor’s MSI status, may modulate both the abundance and biological relevance of the immune regulators TIGIT and CD155, thereby affecting immune evasion and clinical outcome. Accordingly, this study quantified TIGIT and CD155 expression in CRC specimens and paired adjacent non-malignant mucosa, and examined how their expression relates to the examined major oncogenic mutations and MSI status. In addition, we assessed the associations between TIGIT/CD155 levels and a set of chosen 48 cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors measured in tumor tissue to clarify how this checkpoint axis is integrated into the CRC TME and to identify potential biomarkers to support personalized immunotherapeutic strategies.

3. Discussion

TIGIT was identified in 2009 as a coinhibitory receptor that serves as a key modulator of both adaptive and innate immune responses via diverse molecular mechanisms. It is expressed on selected NK cell subsets and B cells, particularly those with regulatory properties, as well as on various T cell subsets, such as regulatory T cells (Tregs), Tr1 cells, T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, and exhausted or dysfunctional CD8

+ T cells. Moreover, TIGIT expression has also been reported on various innate-like lymphocyte populations, such as mucosa-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells, invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells, innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), and macrophages, where its engagement can contribute to amplified immunosuppressive responses within the TME. TIGIT interacts with several nectin and nectin-like ligands, most prominently CD155 (PVR), and also CD112 and CD113. Ligation of TIGIT on dendritic cells (DCs) induces CD155 phosphorylation and triggers downstream MAPK/ERK signaling, promoting the development of immunoregulatory DCs marked by diminished IL-12 production and elevated IL-10 levels, consequently impairing T cell and NK cell activity. In addition, binding of TIGIT to CD155 inhibits IFN-g secretion through β-arrestin-2-dependent suppression of NF-κB signaling and reduces the cytotoxic capacity of NK cells. Elevated expression of TIGIT and CD155 has been demonstrated in multiple human cancers, including melanoma [

37], lung adenocarcinoma [

38], hepatocellular carcinoma [

39], pancreatic cancer [

40], and gastric cancer [

12], among other types of cancer, supporting the relevance of this immune axis as a therapeutic target in oncology.

In CRC, increased expression of TIGIT and CD155 has also been reported, and several studies have suggested a potential prognostic relevance of these molecules. However, the available data on their prognostic significance are still evolving and are not entirely consistent. Kitsou et al. observed that high TIGIT expression tended to be associated with improved overall survival (OS) [

41]. Similarly, in the study by Meyiah et al., which examined combined expression patterns of multiple immune checkpoints rather than single markers, higher frequencies of PD-1

+TIGIT

+ and PD-1

+TIGIT

+ CD8

+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were significantly correlated with longer disease-free survival (DFS) compared with lower frequencies of these subsets. In the same work, the authors validated their findings by analyzing disease-free survival (DFS) and OS according to TIGIT gene expression levels in bulk tumors from the TCGA CRC cohort, showing that patients with high TIGIT expression had better DFS and OS [

42]. By contrast, numerous other studies have linked TIGIT overexpression to unfavorable prognosis and more advanced disease. Cao et al., analyzing transcriptomic data from CRC patients, reported that elevated TIGIT expression was associated with poorer OS and DFS [

43]. In line with this, Shao et al. demonstrated that increased frequencies of CD3

+TIGIT

+ T cells in both peripheral blood and tumor tissue of CRC patients were associated with worse clinical outcome, and that these cells were more abundant than in healthy donors [

44]. Consistently, Liang and Zhu et al. reported higher TIGIT expression in 139 tumor samples compared with 68 normal tissues, along with increased proportions of TIGIT

+CD3

+, TIGIT

+CD4

+, TIGIT

+CD8

+ T cells, and elevated TIGIT expression in NK cells within tumor tissue relative to normal mucosa. Moreover, TIGIT expression was further increased in lymph node and liver metastases compared with primary tumors [

45]. Murakami et al. similarly found elevated levels of both TIGIT and CD155 in cancerous versus normal tissue. In their study, the proportions of TIGIT

+CD3

+, TIGIT

+CD4

+, and TIGIT

+CD8

+ T cells in the peripheral blood of CRC patients were higher than in healthy donors, and these subsets were even more enriched in tumor tissue than in matched blood samples. TIGIT

+CD3

+ T cell infiltration was also greater in tumor tissue than in adjacent normal mucosa, and TIGIT overexpression correlated with tumor progression and adverse prognosis [

46]. In dMMR CRC, both TIGIT protein and mRNA levels were higher in tumor tissue than in adjacent mucosa and were associated with a higher TNM stage [

47]. CD155 expression was shown to be upregulated in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) derived from CRC tissue compared with adjacent non-malignant tissue, and this increase was linked to advanced tumor stage and reduced OS [

48]. Likewise, Liang and Liu et al. reported elevated CD155 expression at both the mRNA and protein levels, with higher expression correlating with poorer prognosis [

49].

The apparent discrepancies between studies reporting either favorable or unfavorable associations of high TIGIT or CD155 expression with clinical outcome in CRC are likely multifactorial. First, TIGIT and CD155 are expressed on phenotypically and functionally diverse cell populations, including tumor cells, tumor-associated macrophages, NK cells, and multiple T cell subsets. Their presence in the TME may be associated with an inflammatory antitumor response, which may result in improved DFS and OS. In contrast, when TIGIT and/or CD155 upregulation predominates on immunosuppressive cell types—such as Tregs or TAMs—or on tumor cells themselves, it may reflect a more advanced state of immune escape and thus associate with poor prognosis. Considerable methodological heterogeneity likely further contributes to these divergent results, as studies differ in analytical methods, such as bulk transcriptomics, IHC, flow cytometry, or ELISA. Tumor-intrinsic features such as MSI status, mutational burden, co-expression of other immune checkpoints, and differences in treatment exposure may also modulate the biological and clinical significance of the TIGIT/CD155 axis. Together, these considerations suggest that the prognostic value of TIGIT and CD155 may be highly context dependent.

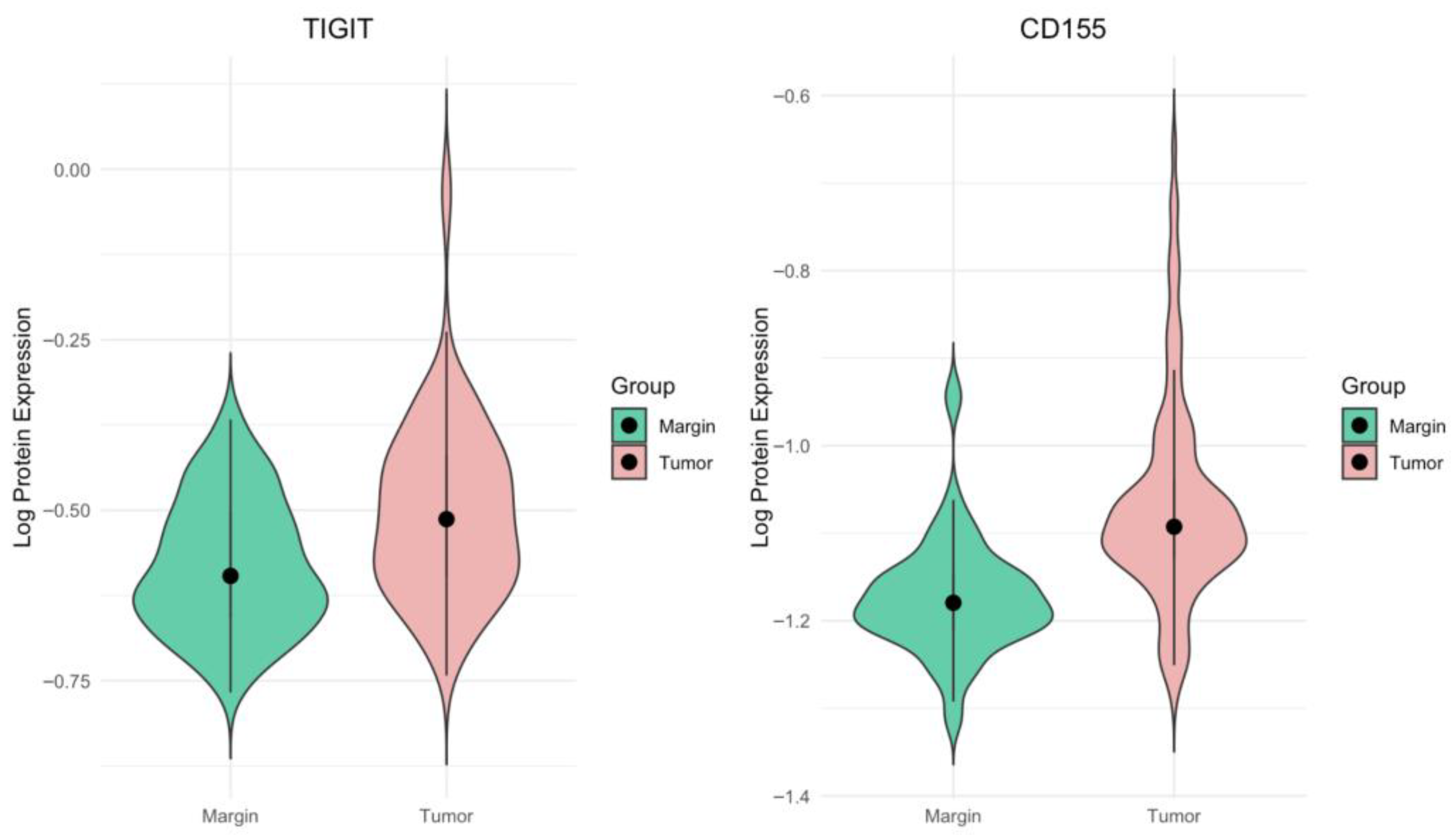

In the present study, we observed a significantly higher expression of both TIGIT and CD155 proteins in CRC tissues compared with matched non-malignant surgical margin samples. The clinical distribution of the patients was similar to that described previously for this cohort, with most cases classified as intermediate stages of disease (stage II and III: 25.19% and 45.80%, respectively), and thus broadly representative of the general CRC population. In our cohort, TIGIT and CD155 protein levels were quantified in tissue homogenates using an ELISA-based approach, providing a measure of their overall abundance within the tumor compartment rather than cell-type-specific or spatially resolved expression. In this setting, we did not detect any significant associations between TIGIT or CD155 concentrations and TNM classification, clinical stage, or histological grade. These findings indicate that, at the level of whole-tissue protein content, upregulation of the TIGIT/CD155 axis appears to be a relatively common feature of CRC that does not segregate with conventional indicators of tumor stage. Methodologically, the use of tissue homogenates integrates signals from tumor cells, stromal elements, and multiple immune cell subsets, which may mask opposing effects exerted by distinct cellular compartments. Thus, the absence of correlations with examined clinicopathological parameters in our study is in line with the notion that the clinical relevance of TIGIT and CD155 likely depends on their distribution across specific immune and tumor cell subsets.

MMR is a highly conserved cellular process that involves a set of proteins responsible for the recognition and subsequent repair of mismatched bases, which arise during DNA replication, genetic recombination, or as a consequence of chemical or physical DNA damage [

50]. MSI is a hypermutable phenotype that results from the loss of DNA mismatch repair activity [

51,

52]. CRC can be broadly categorized into two discrete groups on the basis of mutation patterns: tumors with deficient mismatch repair (dMMR) or a microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) signature and a high overall mutation burden, and tumors with proficient mismatch repair (pMMR) or microsatellite-stable (MSS) status and a much lower mutation burden [

53]. CRCs with MSI-H status demonstrate divergent clinicopathological characteristics, particularly a predilection for the proximal colon, mucinous phenotype, poor differentiation, lower frequencies of KRAS and TP53 mutations, increased immune cell infiltrates, and a reduced rate of metastasis. The majority (~85%) of CRCs are pMMR or MSS and derive little or no benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) monotherapy. The remaining (~15%) of CRCs exhibit MSI, which is characterized by elevated rates of small insertion-deletion mutations and point mutations within microsatellites [

23,

54]. In sporadic CRC, MSI is predominantly caused by epigenetic silencing of MLH1 due to promoter hypermethylation [

55].

Regionalized promoter hypermethylation is a common feature of sporadic MSI-H CRC and is closely associated with the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) [

52,

56]. Hypermethylation of CpG islands (CpGIs) plays a major role in gene inactivation within the TME [

57]. Nair et al. performed a study to analyze whether the promoter methylation profiles of selected immune checkpoint genes, including TIGIT, differ significantly between CRC tumor and non-tumor colorectal tissues [

58]. They demonstrated that the mean demethylation percentage of the TIGIT promoter in CRC tumor tissue was significantly higher than in non-tumor tissue. Moreover, the abundance of the repressive histone mark H3K9me3 in the promoter regions of TIGIT was significantly lower in CRC tumors compared with non-tumor tissues. These findings indicate that transcriptional upregulation driven by promoter demethylation, together with a reduced abundance of repressive histone marks in the TIGIT promoter region, may play an important role in regulating TIGIT expression in the CRC TME [

58]. Although CIMP-high is defined on the basis of focal, high-level hypermethylation of CpG islands, these tumors, like other cancers, also display elements of global hypomethylation in selected genomic regions [

57,

59]. Such a disturbed epigenetic landscape may favor both the silencing of tumor suppressor genes and the derepression of immune-regulatory genes, including TIGIT. In line with the findings of Nair et al., upregulation of TIGIT expression may, therefore, occur via this epigenetic mechanism. Although Nair et al. did not analyze MSI-H and MSS tumors separately, their data support a model of epigenetic derepression of TIGIT that, in the epigenetically unstable context of MSI-H tumors, might be expected to occur more frequently [

58]. By contrast, Kitsou et al. demonstrated that increased TIGIT expression correlated significantly with tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) load, whereas no association was found between high mutational burden and dysregulated TIGIT expression [

41].

Only a limited number of studies have examined the association between TIGIT expression and direct MSI/dMMR status. Zhou et al. analyzed a cohort of 60 dMMR colorectal tumors and showed that TIGIT expression was increased on regulatory T cells (Tregs), but remained low on activated T cells, when compared with normal colonic mucosa [

47]. They also reported higher TIGIT mRNA levels in dMMR tumors relative to matched non-neoplastic tissue. However, this study did not compare TIGIT expression between dMMR/MSI and pMMR/MSS tumors; the analyses were limited to dMMR tumors and normal mucosa as the control group [

47]. Using a different approach, Wen et al. analyzed TCGA data from 33 cancer types and demonstrated that, in CRC, TIGIT expression correlated positively with MSI-related genes and with tumor mutational burden [

60]. Subsequently, Zaravinos et al. based conducted a TCGA analysis, found that high TIGIT expression correlated significantly with increased immune cytolytic activity (CYT) in CRC [

61]. CYT-high tumors exhibited elevated TIGIT expression in both colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) and rectal adenocarcinoma (READ) datasets. TCGA-based analyses from the same study also showed that MSI CRCs have higher expression of several immune checkpoint molecules, including TIGIT, compared with MSS tumors. Zaravinos et al. also demonstrated that CYT is associated with distinct mutational profiles characteristic of CRC, with mutation load being significantly higher in MSI tumors. They also observed that high CYT was significantly associated with BRAF mutations, while no such association was found for KRAS or PIK3CA mutations, which were also evaluated in our study. In addition to these in silico findings, the authors assessed TIGIT expression by RT-qPCR in a cohort of 72 CRC tumors, comprising 12 MSI-H, 13 MSI-L and 47 MSS cases, and demonstrated significantly higher TIGIT expression in MSI-H tumors than in both MSI-L and MSS groups [

61]. The association between CD155 expression and MSI status has been less reported in current data. Zhang et al., using TCGA data, reported negative correlations between CD155 expression and both tumor mutational burden and MSI in CRC [

62].

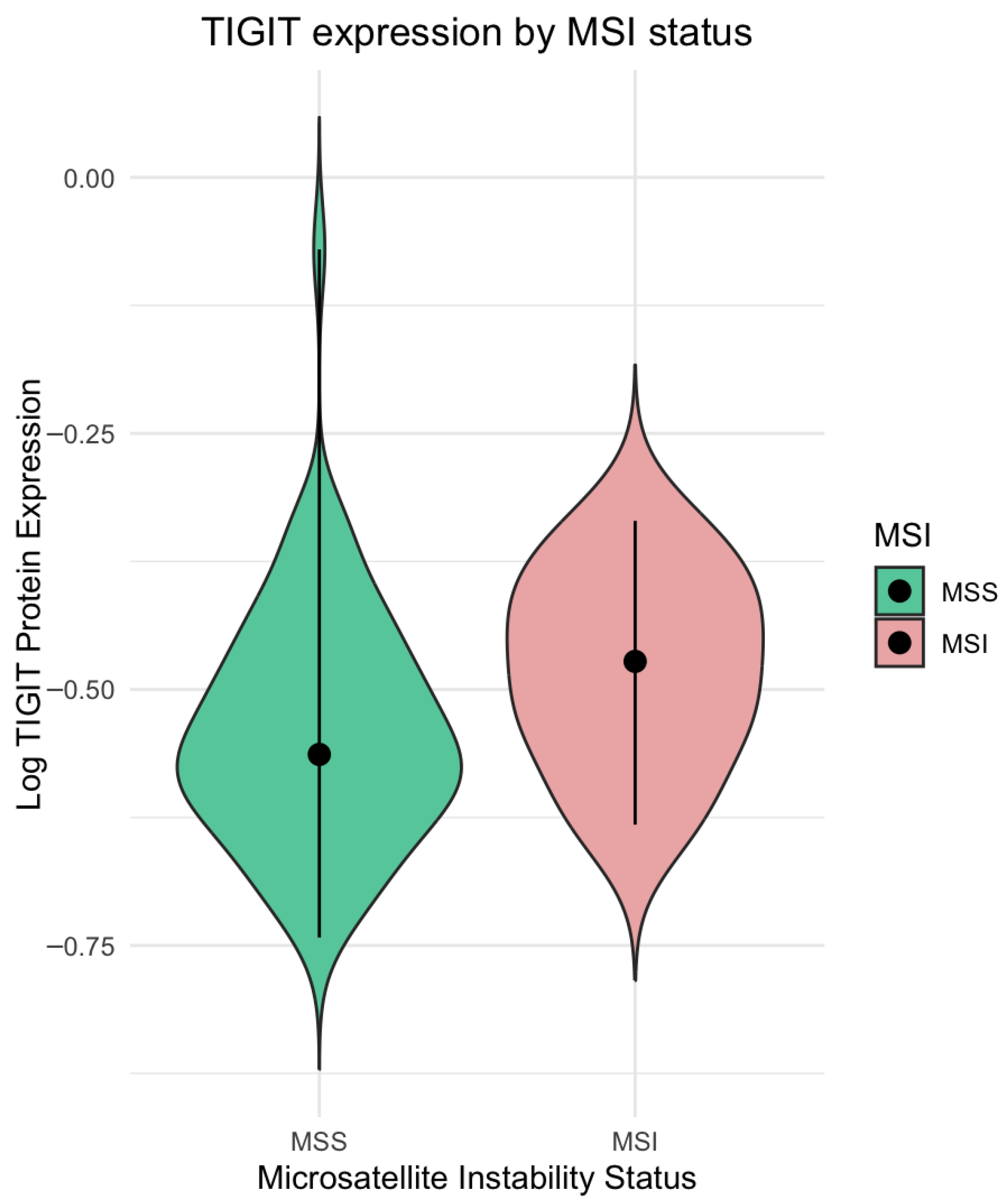

In line with the above findings, our results further support that MSI status is associated with enhanced immune checkpoint expression in CRC. In our cohort, tumors classified as MSI on the basis of IHC assessment of MMR protein loss showed significantly higher TIGIT protein levels compared with the MSS tumor group. These data are consistent with transcriptomic observations from the analyses by Wen et al. and Zaravinos et al., who reported positive associations between TIGIT expression, MSI-related signatures, tumor mutational burden, and immune cytolytic activity in CRC [

34,

35]. Together with the epigenetic data of Nair et al. showing promoter demethylation and reduced H3K9me3 at the TIGIT locus in CRC tissue [

30], our findings support a model in which MSI-driven genomic instability and deregulated epigenetic landscape act in concert with a highly inflamed TME to promote upregulation of TIGIT and other immune checkpoint molecules in MSI CRC. By contrast, we did not observe significant differences in CD155 protein concentrations between MSI and MSS tumors, despite the weak negative correlations between CD155 expression, tumor mutational burden, and MSI reported at the transcriptomic level by Zhang et al. [

36]. This discrepancy may reflect differences between mRNA and protein regulation of CD155. Overall, our data suggest that, within the TIGIT/CD155 axis, TIGIT expression is associated with MSI status at the protein level in CRC, reinforcing the concept that MSI-associated epigenetic and immunological alterations preferentially favor the derepression and induction of immune checkpoint receptors such as TIGIT.

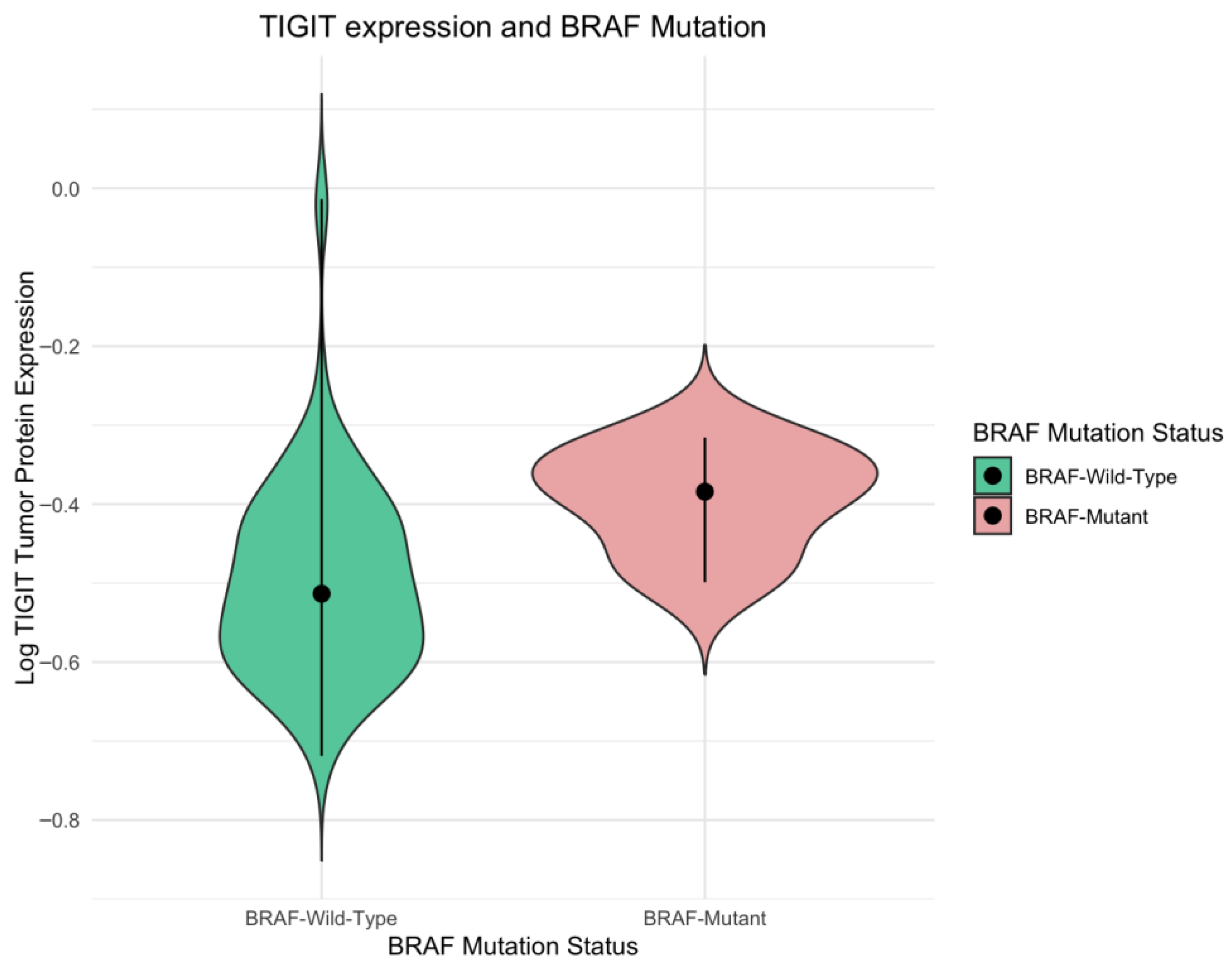

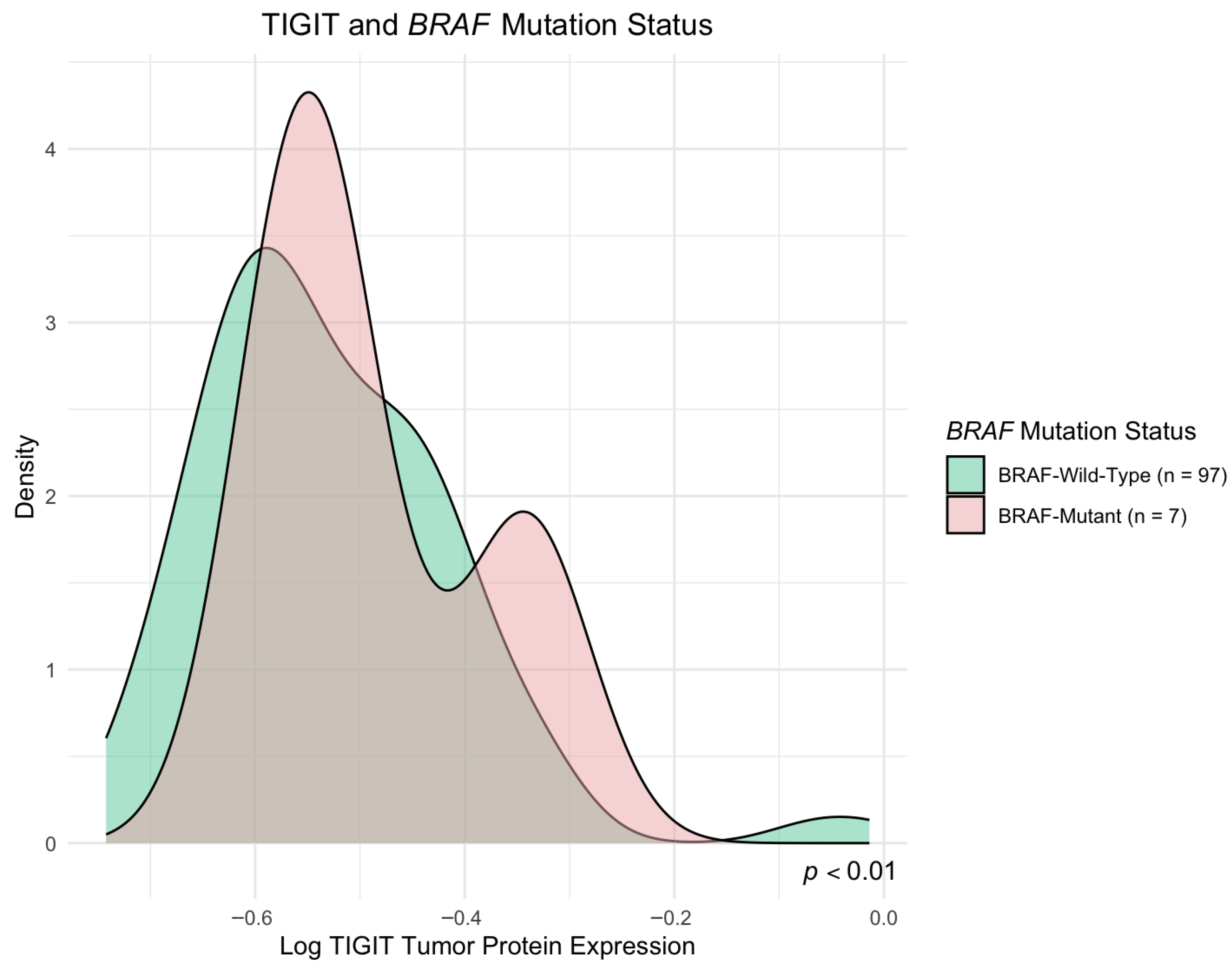

In our study, we observed increased TIGIT protein levels in

BRAF-mutated tumor group compared with the

BRAF wild-type CRC tumor group, whereas no similar association was found for CD155 concentrations. To the best of our knowledge, no previous experimental work has evaluated the associations between

BRAF mutational status and TIGIT/CD155 expression directly. Nevertheless, the influence of

BRAF mutations on the immune TME in CRC is well documented.

BRAF mutations occur in approximately 10% of CRC cases, with over 90% corresponding to the

BRAF V600E variant, and are frequently associated with poor differentiation, advanced T stage, and an elevated risk of metastasis [

30,

31,

63]. Functionally, oncogenic

BRAF drives persistent activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway, which attenuates upstream EGFR/RAS signaling and thereby perturbs antitumor immune surveillance at multiple stages of the cancer-immunity mechanisms [

32,

33,

64]. Moreover,

BRAF mutations often co-occur with MSI status in CRC and, according to the consensus molecular subtype (CMS) classification, define the MSI-immune CMS1 subtype, which is characterized by pronounced immune cell infiltration and activation [

17]. In this context, the elevated expression of immune checkpoint molecules such as TIGIT in

BRAF-mutated tumors is not unexpected. Our findings are thus in line with established pathogenetic evidence in

BRAF-mutated, MSI-immune CRC and reinforce the concept of TIGIT as a relevant immunoregulatory checkpoint that may constitute a particularly promising therapeutic target within this molecular subset of CRC.

KRAS is mutated in approximately 35–45% of sporadic CRC cases and is associated with an unfavorable prognosis [

25,

27,

28,

65].

KRAS mutations are linked to dysregulation of the EGFR and MAPK signaling pathways, which are critically involved in the control of cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and senescence [

27]. Beyond these well-established oncogenic functions,

KRAS mutation may also exert an impact on the immunological landscape of the CRC TME. According to Lal et al.,

KRAS mutation in CRC is associated with a globally more immunosuppressed TME, characterized by attenuation of Th1/cytotoxic immunity.

KRAS-mutant tumors have reduced expression of a Th1-centric co-ordinate immune response cluster (CIRC), with particularly lower infiltration of cytotoxic T cells, Th1 cells, and neutrophils, and broad downregulation of multiple immune-related Hallmark pathways, most notably the interferon-g pathway [

66]. Moreover, according to a study by Edin et al.,

KRAS mutation in CRC is consistently associated with a less inflamed, more immunosuppressed TME. Using the IHC method on tumor front and center, the authors show that

KRAS-mutated tumors have significantly lower infiltration of CD8

+ cytotoxic T cells and T-bet

+ Th1 cells compared with

KRAS wild-type cases, particularly at the tumor front, where immune-tumor interactions are most critical. In the tumor center, similar but weaker patterns are seen, and

KRAS mutation is additionally linked to increased regulatory T cell (FoxP3

+) infiltration, further supporting an immunosuppressive phenotype [

67].

KRAS-driven tumors also show broader metabolic and signaling changes (including dysregulated glucose/glutamine/fatty acid metabolism and activation of MAPK and HIF-1-related cascades) that support tumor growth and indirectly reinforce immune escape [

29]. Taken together, the available data indicate that oncogenic

KRAS does not simply reduce the quantity of TILs but qualitatively remodels the immune landscape in a way that is highly relevant for immune checkpoint regulation. When integrating these data with our own results, it is important to note that, despite the strong mechanistic basics for

KRAS-driven immune remodeling, we did not observe significant differences in TIGIT or CD155 protein levels between

KRAS-mutant and

KRAS-wild-type tumors in our cohort, as measured by ELISA in tissue homogenates. In our study, we have observed significantly higher CD155 concentration in

KRAS codon 146 mutated tumors. However, given the limited number of cases harboring the

KRAS codon 146 mutation in our cohort, the observed association with CD155 should be considered exploratory, and it warrants validation in larger, independent cohort. This apparent discrepancy suggests that the impact of

KRAS on immune checkpoint regulation may be more qualitative and compartment-specific than reflected by total tissue concentrations. In particular,

KRAS mutation has been linked to shifts in the composition and functional state of tumor-infiltrating immune cells rather than to a uniform increase or decrease in global TIGIT/CD155 expression across the entire tissue. These observations underscore the need for cell type-resolved and spatially approaches, to more precisely dissect how

KRAS mutations reshape TIGIT-dependent regulatory molecules within the CRC TME.

TIGIT

+CD8

+ T cells have been shown to secrete lower levels of IFN-g, IL-2, and TNF compared to TIGIT

−CD8

+ T cells, highlighting how TIGIT can impair CD8

+ T cell function. Furthermore, TIGIT was found to modulate the expression of receptors such as TIGIT, LAG-3, and PD-1 on CD8

+ T cells, contributing to T cell exhaustion [

45]. As reported by Li et al., blocking TIGIT increases the percentage of cytokine-secreting CD8

+ T cells and activates the NF-κB pathway [

68]. Huang et al. demonstrated the role of TIGIT and CD155 in regulating CD8

+ T cell glucose metabolism via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, resulting in subsequent modifications in the TME and cytokine production [

69]. TIGIT has also been shown to play a crucial role in other types of cancer. In gastric cancer, CD8

+ T cells expressing the TIGIT receptor were involved in regulating a number of different processes within the TME, including proliferation, metabolism, and cytokine secretion. TIGIT signaling reduced AKT/mTOR pathway activation through decreased phosphorylation [

12]. In castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), TIGIT inhibition increased NK cell-mediated chemotaxis of T cells, improved cytotoxicity against CRPC cells, and cytokine production. Additionally, the MEK/ERK and NF-κB signaling pathways were shown to be involved in these changes [

70]. CD155 can regulate cell motility and proliferation in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. It increases platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-mediated Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK activation by acting downstream of the PDGF receptor and upstream of Ras [

71]. In ESCA, CD155 expression was found to be correlated with PD-1 and PD-L1. Furthermore, CD155 was associated with cell proliferation, and its downregulation led to decreased proliferation by disrupting the cell cycle and inducing apoptosis, supposedly through the inhibition of the PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways [

72]. CD155 was suggested to be involved in angiogenesis. It may regulate VEGF-meditated angiogenesis through modulation of the interaction between VEGFR2 and integrin avβ3. It was reported to be involved in regulation of the VEGFR2-mediated Rap1-Akt signaling pathway [

73]. Briukhovetska et al. reported that IL-22 can induce the expression of CD155, which binds to CD226, activating NK cells. However, excessive activation led to decreased CD226 expression, altered NK cell activity, and reduced IFN-g secretion, ultimately increasing the metastatic properties of lung cancer cells [

74].

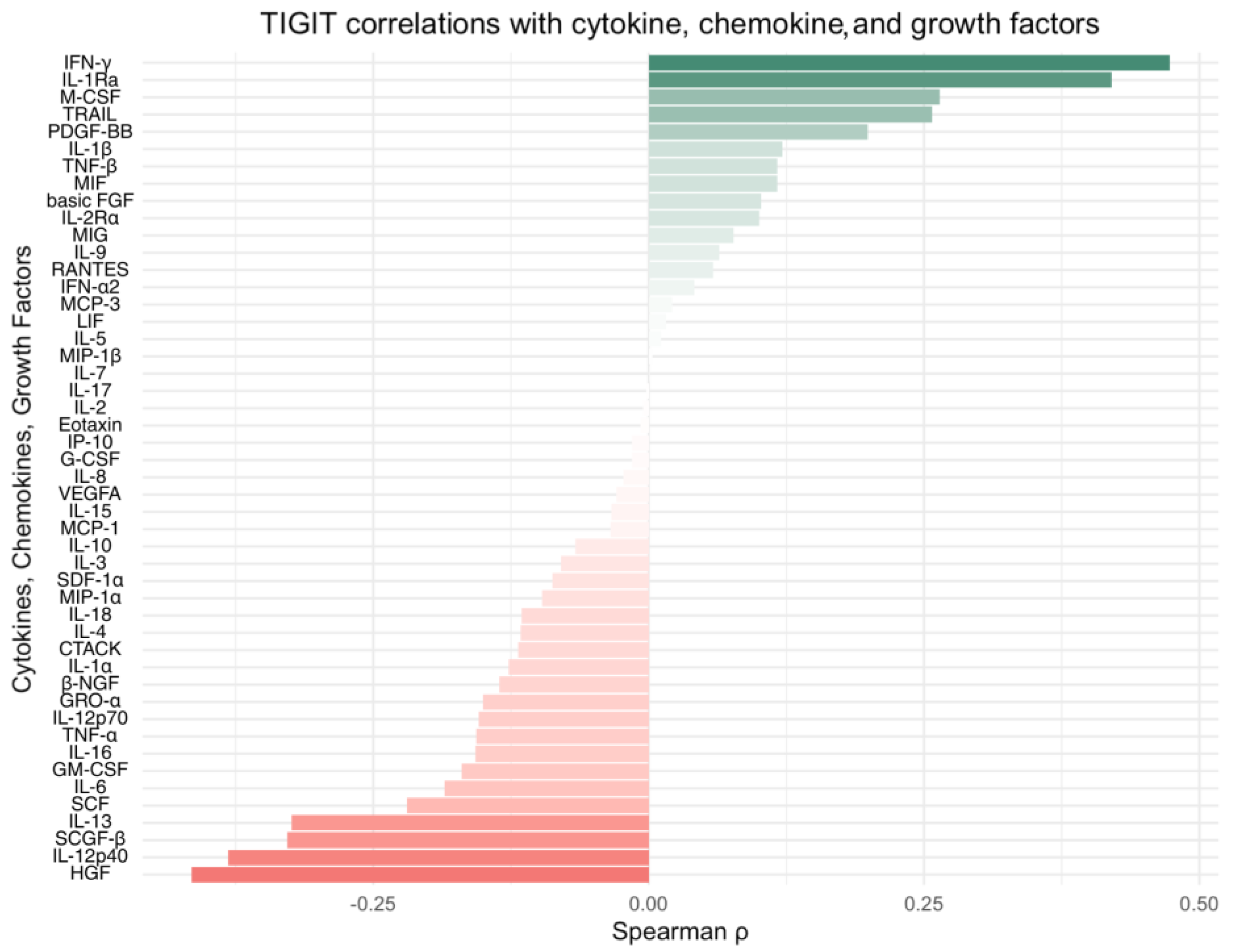

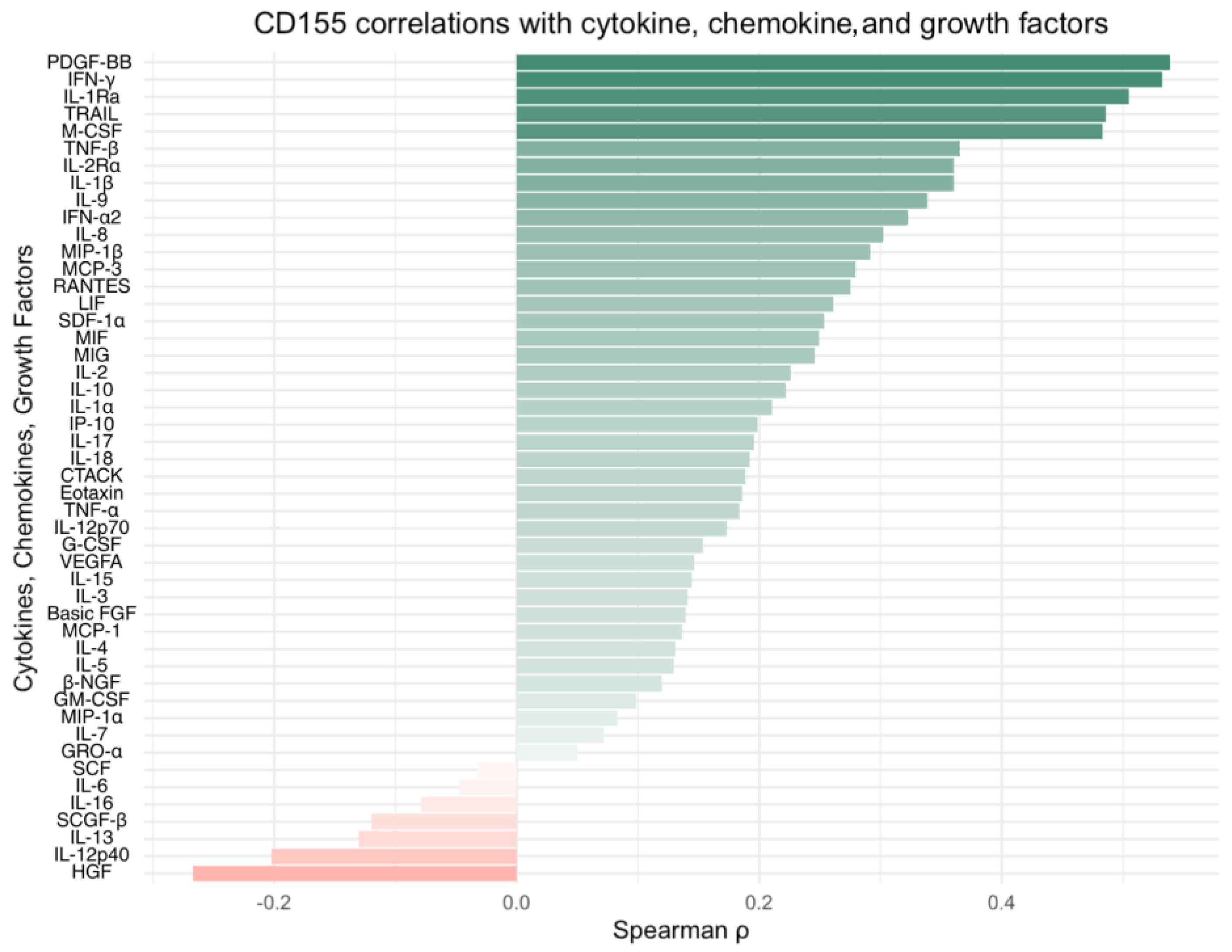

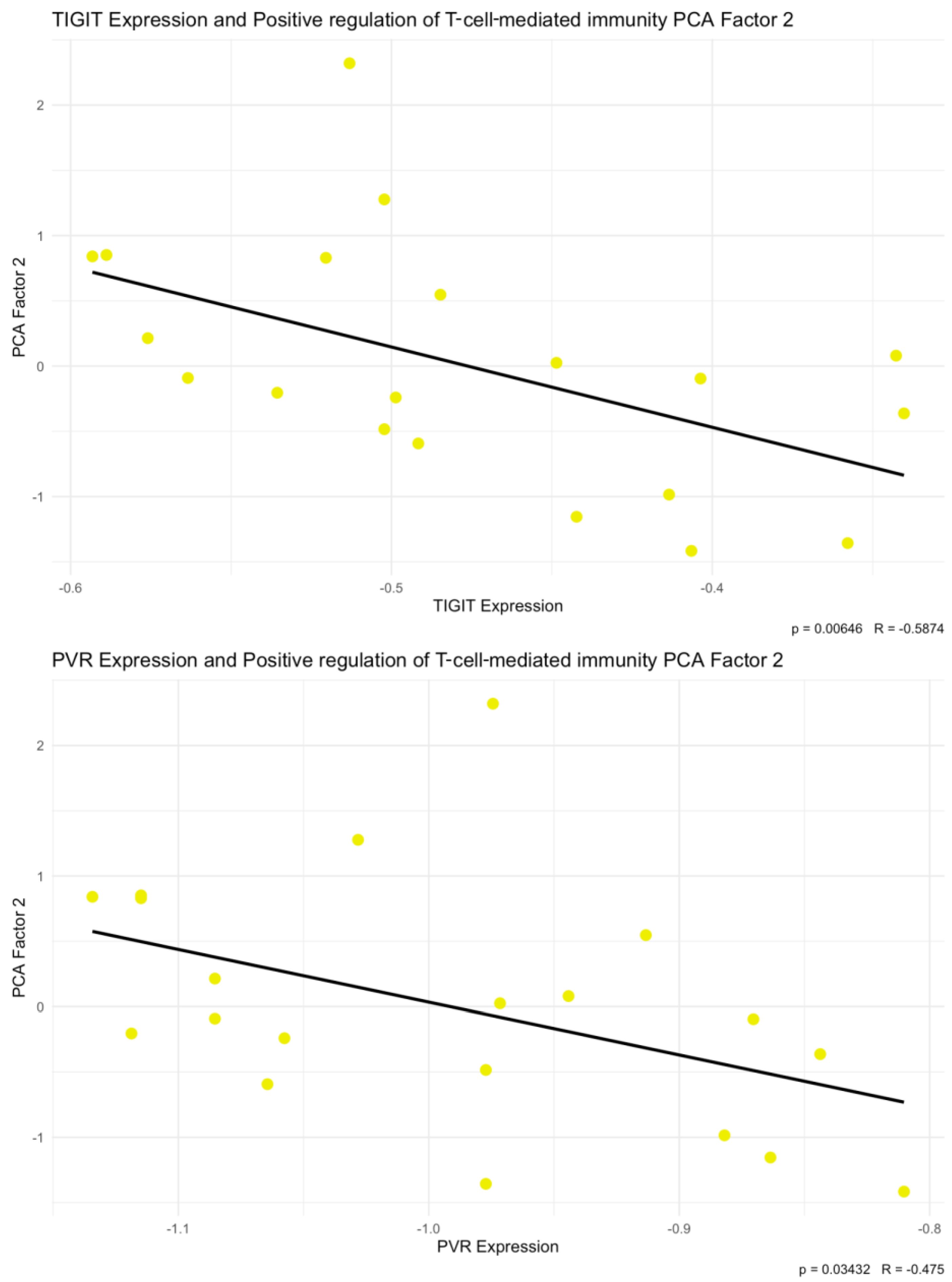

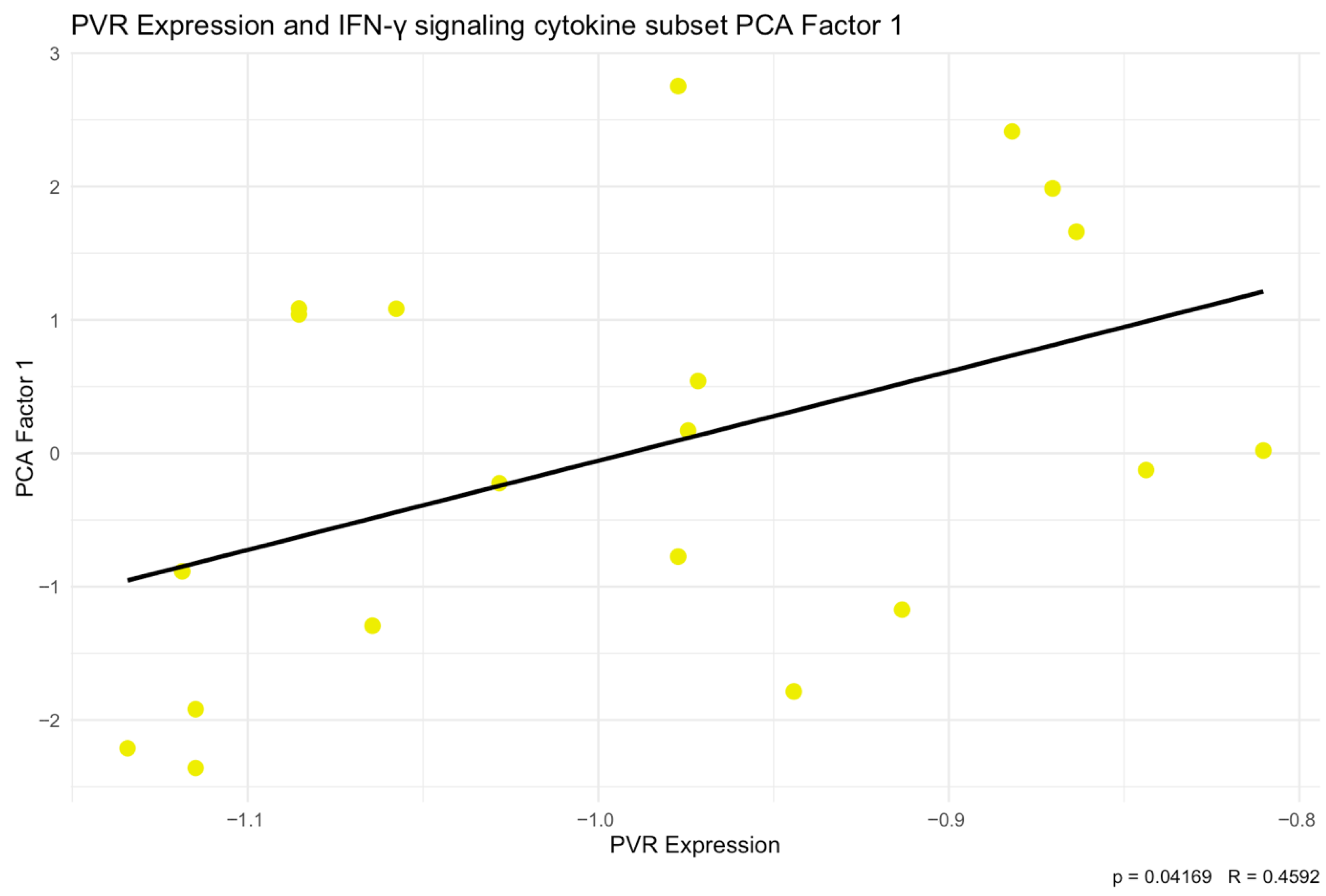

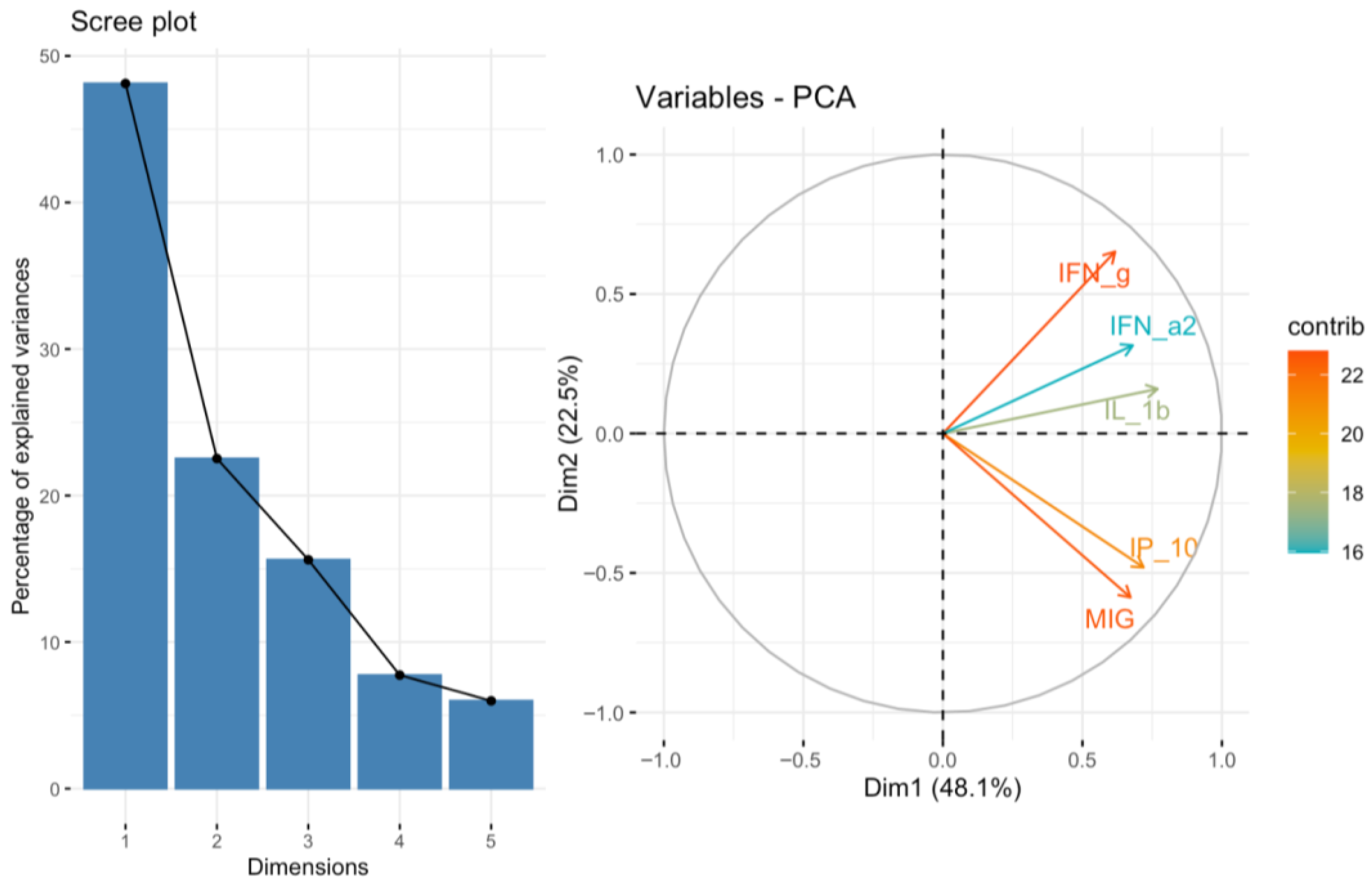

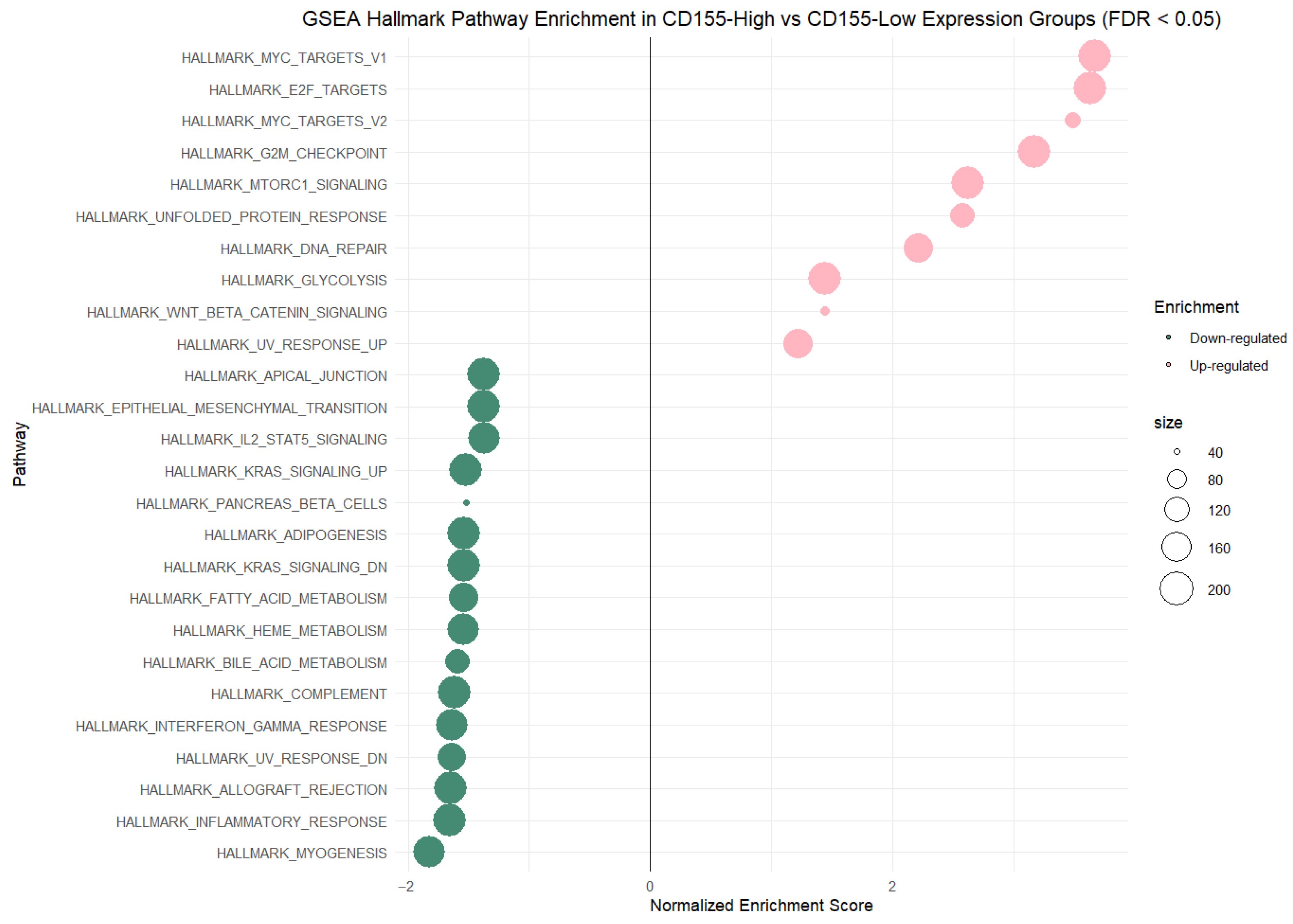

Integration of our own cytokine correlation analysis and GSEA results suggests that the TIGIT/CD155 immune checkpoint axis may be associated with multiple immune-related pathways in CRC tumor tissues. In our protein measurements of selected 48 cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, only a few significant correlations were detected, but IFN-g distinguish as a shared correlate, showing positive associations with TIGIT and CD155. CD155 was also positively correlated with TRAIL, IL-1Ra, M-CSF, and PDGF-bb, suggesting that higher CD155 can accompany a broader inflammatory or growth-factor tumor milieu. These experimental findings fit well with the indicated GSEA results: TIGIT-high samples were enriched for immune and inflammation-related pathways, including the IFN-g response, consistent with TIGIT marking a more immune-inflamed TME in tumor tissues. In contrast, CD155-high samples were enriched mainly for proliferation and growth programs (MYC/E2F/G2M signatures), while immune/inflammatory pathways (including IFN-related programs) were more prominent in CD155-low, producing an apparent opposite pattern between TIGIT and CD155 at the pathway level. Importantly, this does not conflict with previous functional studies showing that TIGIT/CD155 signaling can reduce IFN-g production by T and NK cell [

45,

74]. In bulk CRC tumors, positive correlations can still occur because immune-inflamed samples often show both higher IFN-g and higher checkpoint molecules, reflecting immune activation together with feedback inhibition, which means that higher immune checkpoint expression may reduce further immune activation and cytokine production in consequence. Moreover, integrating our experimental PCA/correlation results with the GSEA findings places TIGIT in CRC firmly in the context of an IFN-g-driven, immune-inflamed TME, where active antitumor immunity coexists with checkpoint-mediated restraint. As an inhibitory receptor on T and NK cells, TIGIT is plausibly induced as part of adaptive immune resistance: sustained IFN-g signaling and downstream IFN-g–dependent cytokine programs reflect immune engagement, while concomitant TIGIT upregulation may potentially represent a compensatory inhibition that can limit cytotoxic effector function and promote functional exhaustion. Translationally, this co-occurrence suggests that TIGIT-high/IFN-g-high CRC tumors may define a clinically actionable subgroup characterized by pre-existing immune activation but incomplete tumor rejection, in which a therapeutic strategy based on inhibitory signaling could be potentially beneficial. In contrast, CD155 showed a broader association pattern that included growth-factor and myeloid/stromal mediators, such as PDGF-bb, M-CSF, and TRAIL and, at the pathway level, preferential enrichment of proliferative programs (MYC/E2F/G2M), suggesting that CD155 abundance in bulk tissue may more strongly reflect tumor/stromal remodeling and tumor cell–intrinsic programs than immune activation alone. Importantly, this divergence implies that interpreting the TIGIT/CD155 axis and prioritizing TIGIT-directed immunotherapy strategies may require patient stratification by immune context (MSI/BRAF-associated immune-inflamed subsets) because TIGIT-high tumors could represent settings where combination checkpoint blockade is biologically more plausible, whereas CD155-high tumors may indicate a proliferative, microenvironmentally remodeled state that could benefit from different or additional combinatorial approaches. The precise associations between the TIGIT/CD155 axis proteins and interferon-related signaling in CRC require further investigation. Future studies using approaches that resolve cell-type specificity and enable functional testing will be needed to determine whether these associations reflect a direct regulatory link or are driven primarily by differences in CRC TME composition.

The TIGIT/CD155 axis is considered as a potential therapeutic target in many solid tumors. In Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC), both in vitro and in vivo blockade of TIGIT increased antitumor immune responses. In vitro studies showed decreased immunosuppressive ability of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), supposedly achieved by decreased expression of Arg1, and Tregs by decreased TGFβ1 secretion. In vivo studies showed that blockade of TIGIT results in activation of CD8

+ T cells, increasing their effector function and lowering number of Tregs [

75]. In an ovarian cancer (OC) mouse model, TIGIT function was blocked using Anti-TIGIT monoclonal antibodies. This resulted in decreased proportion of CD4

+ Tregs, while no effect was observed on CD4

+ and CD8

+ T cells or NK cells. TIGIT inhibition diminished the immunosuppressive activity of splenic CD4

+ Tregs. Moreover, anti-TIGIT treatment improved the survival rate of OC mice [

76]. Johnston et al. reported that blockade of both TIGIT and PDL1 in CT26 tumor-bearing mice significantly reduced tumor growth and led to complete responses in most mice. Similar results were observed in other tumor models [

77]. First-in-human phase 1 study of anti-TIGIT antibody vibostolimab plus pembrolizumab was well tolerated in advanced solid tumors and demonstrated antitumor activity [

78]. In the CITYSCAPE study, 135 patients with chemotherapy-naive, PD-L1-positive, recurrent or metastatic NSCLC received tiragolumab plus atezolizumab or placebo plus atezolizumab. It was observed that the group of tiragolumab plus atezolizumab had higher response rates and progression-free survival in comparison to placebo plus atezolizumab. The combination was tolerated, with a safety profile similar to atezolizumab in monotherapy, supporting its potential as a promising treatment option [

79]. Overall, anti-TIGIT antibodies show limited efficacy in terms of monotherapy. However, its combination with anti-PD-(L)1 shows better results. Lack of biomarkers, which could predict efficacy of such treatment strategy, limits possible optimization of such immune therapies [

80,

81]. In terms of CD155 inhibition, there are limited studies. However, recombinant nonpathogenic polio-rhinovirus chimera (PVSRIPO), which targets CD155, was shown to be a possible therapeutic option in GBM [

82].

Our findings have potential implications for TIGIT/CD155-directed immunotherapy in CRC, particularly in molecularly defined subgroups. We observed higher TIGIT protein levels in MSI tumors and in BRAF-mutant CRC, suggesting that TIGIT upregulation may mark an immune-inflamed context in which checkpoint blockade strategies could be especially relevant. In line with this, our cytokine analysis identified IFN-g as a shared positive associate of both TIGIT and CD155, which is consistent with the idea that immune activation and compensatory checkpoint upregulation can co-occur in tumor tissue. Given that anti-TIGIT monotherapy has generally shown limited efficacy, while combinations with anti-PD-(L)1 perform better in several settings, our data support the rationale for exploring TIGIT blockade as an add-on strategy, potentially with greatest value in MSI and/or BRAF-mutant CRC, where TIGIT/CD155 expression could be significantly upregulated.

Despite the results we observed in this study, there are significant limitations of this study, stemming from the methods used, that should be noted. An important limitation of this study is that TIGIT and CD155 were quantified in whole-tissue homogenates, which integrate signals from tumor cells, stromal elements, and multiple immune cell subsets. As a result, this approach cannot resolve the cellular source or spatial localization of the measured proteins: whether CD155 derives predominantly from malignant epithelial cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts/endothelium, or tumor-associated macrophages, and whether TIGIT reflects exhausted CD8+ T cells, Tregs, or other lymphocyte compartments. It may, therefore, mask opposing effects occurring in distinct TME niches. A second key limitation is that we assessed only TIGIT and CD155 without parallel evaluation of CD226 (DNAM-1) and CD96 (TACTILE), which compete for CD155 binding and can deliver signals with different (activating vs. inhibitory and context-dependent) functional consequences. Accordingly, we could not quantify the counterbalance within the CD155-(TIGIT/CD226/CD96) receptor network that ultimately shapes immune responses. The lack of in situ analyses, such as IHC/IF or cell-based profiling, further limits interpretation by precluding direct attribution of expression patterns to specific compartments and by not accounting for CRC tumors’ heterogeneity. For instance, CD155 expression may arise from non-mutant tumor subclones or from non-malignant stromal cells, which complicates mutation-expression associations in bulk tissue. Finally, our conclusions are based on cross-sectional measurements and correlations without functional validation of how the TIGIT/CD155 axis affects effector activity in CRC, and differences between mRNA and protein regulation, as well as pre-analytical factors (tissue composition, variable stromal content, and protein stability) may influence protein concentrations measured in homogenates.