The Role of Vitamin D in Autoimmune Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

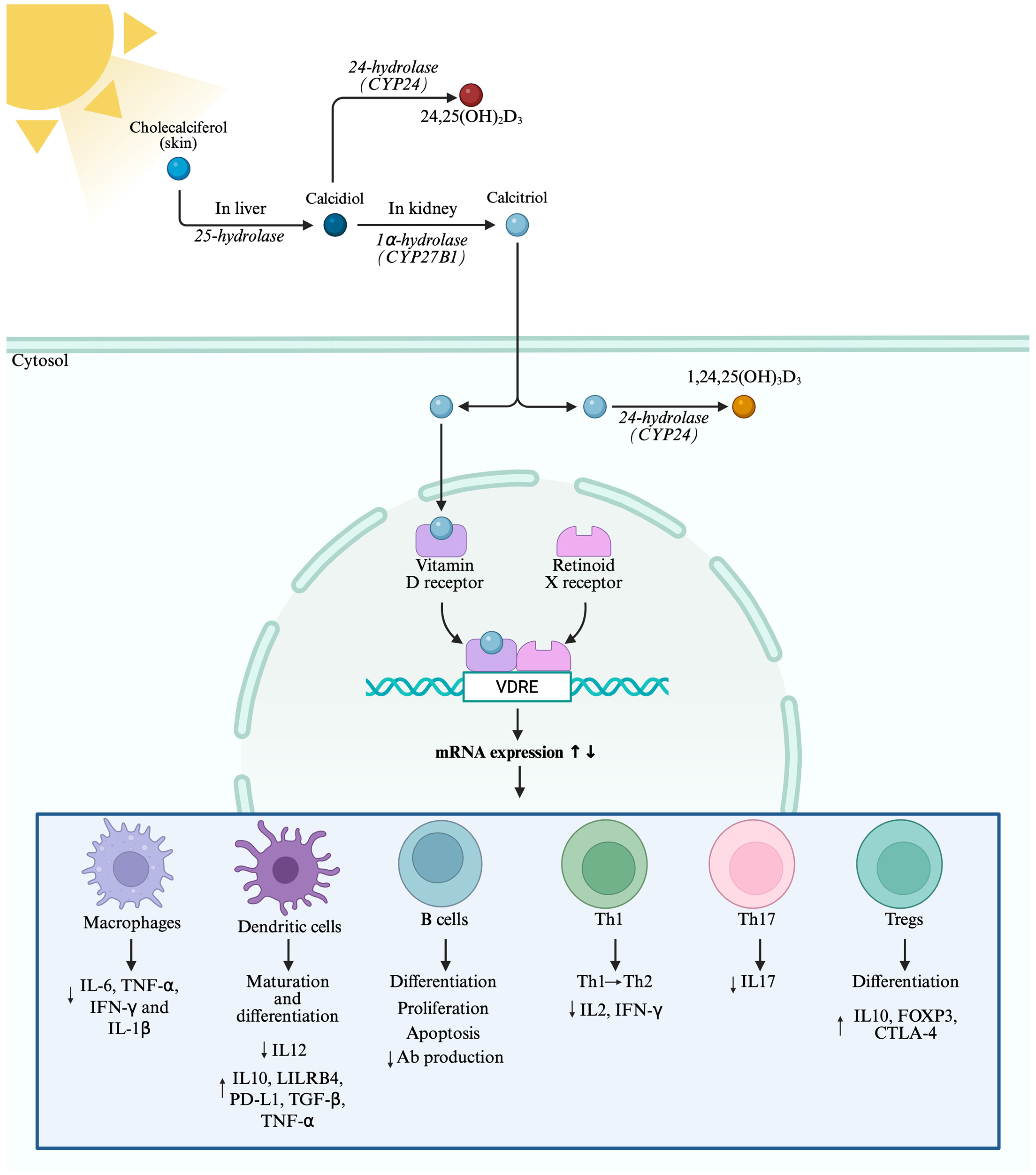

2. Vitamin D Metabolism and Function

3. Vitamin D and Innate Immunity

3.1. Macrophages

3.2. Dendritic Cell Modulation

4. Vitamin D and Adaptive Immunity

4.1. B Cells

4.2. T Cells

5. Vitamin D in Autoimmune Diseases

5.1. Multiple Sclerosis

5.2. Rheumatoid Arthritis

5.3. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

5.4. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

6. Translational Gap Between Pre-Clinical Models and Human Autoimmune Diseases

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 1,24,25(OH)3D3 | 1,24,25-Trihydroxycholecalciferol |

| 24,25(OH)2D3 | 24,25-Dihydroxycholecalciferol |

| 3D HR-pQCT | 3-Dimensional High-Resolution Peripheral Quantitative Computed Tomography |

| Ab | Antibody |

| ACPA | Anti-Citrullinated Protein Antibodies |

| anti-C1q | Anti-Complement Component 1q |

| anti-dsDNA | Anti-Double-Strand DNA |

| AP-1 | Activator Protein 1 |

| ARR | Annualized Relapse Rate |

| BACH | BTB Domain And CNC Homolog 1 |

| BALB | Bagg’s Albino |

| BAX | BCL2 Associated X, Apoptosis Regulator (Bax) |

| BBB | Blood–Brain Barrier |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic Acid |

| BCL-2 | B Cell Lymphoma 2 |

| C57BL/6 | Black 6 |

| CatG | Cathepsin G |

| CD | Cluster Differentiation |

| CIS | Clinically Isolated Syndrome |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CT | Conventional Therapy |

| CTLA-4 | Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4 |

| CUA | Combined Unique Active |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 |

| CYP27B1 | 1α-Hydroxylase |

| DCs | Dendritic Cells |

| DKA | Diabetic Ketoacidosis |

| EAE | Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis |

| ECLAM | European Consensus Lupus Activity Measurement |

| EDSS | Expanded Disability Status Scale |

| ERK | Extracellular-Signal-Regulated Kinases |

| F | Female |

| FOXP3 | Forkhead Box P3 |

| FSMC | Fatigue Scale for Motor and Cognitive Functions |

| GADA | Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase Autoantibodies |

| GATA-3 | GATA Binding Protein 3 |

| Gfi1 | Growth Factor Independent 1 Transcriptional Repressor |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte–Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| HbA1c | Glycated Hemoglobin |

| HE | Hematoxylin–Eosin |

| HPCs | Immortalized Human Podocytes |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| IFN | Interferon |

| Ig | Immunoglobulin |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| IKKβ | Inhibitor Of Nuclear Factor Kappa B Kinase Subunit Beta |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IRF4 | Interferon Regulatory Factor 4 |

| IU | International Units |

| IκBα | Nuclear Factor Of Kappa Light Polypeptide Gene Enhancer in B cells Inhibitor Alpha |

| JAK | Janus Kinase |

| JNK | c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase |

| LILRB4 | Leukocyte Immunoglobulin-Like Receptor Subfamily B member 4 |

| LN | Lupus Nephritis |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| M | Male |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| mDCs | Myeloid-Derived DCs |

| MHC | Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| miR | Micro-RNA |

| MMTT | Mixed-Meal Tolerance Test |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MRL/lpr | Murphy Roths Large/lymphoproliferation |

| mRTECs | Mouse Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells |

| MS | Multiple Sclerosis |

| MTX | Methotrexate |

| NEDA-3 | No Evidence of Disease Activity-3 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells |

| NFAT | Nuclear Factor of Activated T cells |

| NLRP3 | NLR Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 |

| NOD | Non-Obese Diabetic |

| NZB × W F1 | New Zealand Black x New Zealand White F1 |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| PBMCs | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| pDCs | Plasmacytoid DCs |

| PIL | Pristane-induced Lupus |

| PTH | Parathyroid Hormone |

| qPCR | Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RA | Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| RF | Rheumatoid Factor |

| RRMS | Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RXR | Retinoid-X-Receptor |

| sh-CatG | Short-Hairpin RNA against CatG |

| SLE | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus |

| SLEDAI | Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index |

| SNPs | Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms |

| SOCS | Suppressor of Cytokine Signaling |

| STAT | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| T1D | Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus |

| T2w | T2-weighted |

| tDCs | Tolerogenic DCs |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| TGF | Transforming Growth Factor |

| Th | T Helper Cells |

| TLR | Toll-Like Receptors |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| Tregs | Regulatory T Cells |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| VDBP | Vitamin D Binding Protein |

| VDR | Vitamin D Receptor |

| VDR−/− hTNFtg | VDR Knockout Human Tumor Necrosis Factor α Transgenic |

| VDREs | Vitamin D Response Elements |

| WB | Western Blot |

References

- Papagni, R.; Pellegrino, C.; Di Gennaro, F.; Patti, G.; Ricciardi, A.; Novara, R.; Cotugno, S.; Musso, M.; Guido, G.; Ronga, L.; et al. Impact of Vitamin D in Prophylaxis and Treatment in Tuberculosis Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, R.F.; Liu, P.T.; Modlin, R.L.; Adams, J.S.; Hewison, M. Impact of Vitamin D on Immune Function: Lessons Learned from Genome-Wide Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Arbesman, J.; Piliang, M. Vitamin D. Autoimmunity and Immune-Related Adverse Events of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2021, 313, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formisano, E.; Proietti, E.; Borgarelli, C.; Pisciotta, L. Psoriasis and Vitamin D: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brożyna, A.A.; Slominski, R.M.; Nedoszytko, B.; Zmijewski, M.A.; Slominski, A.T. Vitamin D Signaling in Psoriasis: Pathogenesis and Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernia, F.; Valvano, M.; Longo, S.; Cesaro, N.; Viscido, A.; Latella, G. Vitamin D in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Implications. Nutrients 2022, 14, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorini, F.; Tonacci, A. Vitamin D: An Essential Nutrient in the Dual Relationship between Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases and Celiac Disease-A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infantino, C.; Francavilla, R.; Vella, A.; Cenni, S.; Principi, N.; Strisciuglio, C.; Esposito, S. Role of Vitamin D in Celiac Disease and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durá-Travé, T.; Gallinas-Victoriano, F. Autoimmune Thyroiditis and Vitamin D. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Resurrection of Vitamin D Deficiency and Rickets. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 2062–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakos, S.; Dhawan, P.; Verstuyf, A.; Verlinden, L.; Carmeliet, G. Vitamin D: Metabolism, Molecular Mechanism of Action, and Pleiotropic Effects. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 96, 365–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Gordon, C.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Heaney, R.P.; Murad, M.H.; Weaver, C.M. Evaluation, Treatment, and Prevention of Vitamin D Deficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930, Erratum in J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, e1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D Deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 357, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, G.; Prosser, D.E.; Kaufmann, M. Cytochrome P450-Mediated Metabolism of Vitamin D. J. Lipid Res. 2014, 55, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dusso, A.S.; Brown, A.J.; Slatopolsky, E.; Vitamin, E.S.; Slatopolsky, E. Vitamin D. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2005, 289, F8–F28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khammissa, R.A.G.; Fourie, J.; Motswaledi, M.H.; Ballyram, R.; Lemmer, J.; Feller, L. The Biological Activities of Vitamin D and Its Receptor in Relation to Calcium and Bone Homeostasis, Cancer, Immune and Cardiovascular Systems, Skin Biology, and Oral Health. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 9276380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D Metabolism, Mechanism of Action, and Clinical Applications. Chem. Biol. 2014, 21, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeyama, K.I.; Kato, S. The Vitamin D3 Lalpha-Hydroxylase Gene and Its Regulation by Active Vitamin D3. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011, 75, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khundmiri, S.J.; Murray, R.D.; Lederer, E. PTH and Vitamin D. Compr. Physiol. 2016, 6, 561–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hii, C.S.; Ferrante, A. The Non-Genomic Actions of Vitamin D. Nutrients 2016, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, C.J.; Adams, J.S.; Bikle, D.D.; Black, D.M.; Demay, M.B.; Manson, J.A.E.; Murad, M.H.; Kovacs, C.S. The Nonskeletal Effects of Vitamin D: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr. Rev. 2012, 33, 456–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, J.S.; Warrington, R.; Watson, W.; Kim, H.L. An Introduction to Immunology and Immunopathology. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2018, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.T.; Stenger, S.; Li, H.; Wenzel, L.; Tan, B.H.; Krutzik, S.R.; Ochoa, M.T.; Schauber, J.; Wu, K.; Meinken, C.; et al. Toll-like Receptor Triggering of a Vitamin D-Mediated Human Antimicrobial Response. Science 2006, 311, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.S.; Hewison, M. Unexpected Actions of Vitamin D: New Perspectives on the Regulation of Innate and Adaptive Immunity. Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 4, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenngam, N.; Holick, M.F. Immunologic Effects of Vitamin d on Human Health and Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranow, C. Vitamin D and the Immune System. J. Investig. Med. 2011, 59, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewison, M. Vitamin D and the Intracrinology of Innate Immunity. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2010, 321, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffels, K.; Overbergh, L.; Giulietti, A.; Verlinden, L.; Bouillon, R.; Mathieu, C. Immune Regulation of 25-Hydroxyvitamin-D3-1α-Hydroxylase in Human Monocytes. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2006, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Sun, T.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Deb, D.K.; Yoon, D.; Kong, J.; Thadhani, R.; Li, Y.C. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D Promotes Negative Feedback Regulation of TLR Signaling via Targeting MicroRNA-155–SOCS1 in Macrophages. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 3687–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Lahav, M.; Shany, S.; Tobvin, D.; Chaimovitz, C.; Douvdevani, A. Vitamin D Decreases NFκB Activity by Increasing IκBα Levels. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2006, 21, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Leung, D.Y.M.; Richers, B.N.; Liu, Y.; Remigio, L.K.; Riches, D.W.; Goleva, E. Vitamin D Inhibits Monocyte/Macrophage Proinflammatory Cytokine Production by Targeting MAPK Phosphatase-1. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 2127–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adorini, L.; Penna, G. Dendritic Cell Tolerogenicity: A Key Mechanism in Immunomodulation by Vitamin D Receptor Agonists. Hum. Immunol. 2009, 70, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suuring, M.; Moreau, A. Regulatory Macrophages and Tolerogenic Dendritic Cells in Myeloid Regulatory Cell-Based Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hewison, M. Vitamin D and Immune Function: An Overview. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2012, 71, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanherwegen, A.S.; Gysemans, C.; Mathieu, C. Vitamin D Endocrinology on the Cross-Road between Immunity and Metabolism. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2017, 453, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penna, G.; Adorini, L. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Inhibits Differentiation, Maturation, Activation, and Survival of Dendritic Cells Leading to Impaired Alloreactive T Cell Activation. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 2405–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Lewis, E.D.; Pae, M.; Meydani, S.N. Nutritional Modulation of Immune Function: Analysis of Evidence, Mechanisms, and Clinical Relevance. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolf, L.; Muris, A.H.; Hupperts, R.; Damoiseaux, J. Vitamin D Effects on B Cell Function in Autoimmunity. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2014, 1317, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, G.; Niesner, U.; Chang, H.D.; Steinmeyer, A.; Zügel, U.; Zuberbier, T.; Radbruch, A.; Worm, M. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Promotes IL-10 Production in Human B Cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2008, 38, 2210–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaseminejad-Raeini, A.; Ghaderi, A.; Sharafi, A.; Nematollahi-Sani, B.; Moossavi, M.; Derakhshani, A.; Sarab, G.A. Immunomodulatory Actions of Vitamin D in Various Immune-Related Disorders: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 950465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artusa, P.; White, J.H. Vitamin D and Its Analogs in Immune System Regulation. Pharmacol. Rev. 2025, 77, 10032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantorna, M.T.; Snyder, L.; Lin, Y.D.; Yang, L. Vitamin D and 1,25(OH)2D Regulation of T Cells. Nutrients 2015, 7, 3011–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery, L.E.; Burke, F.; Mura, M.; Zheng, Y.; Qureshi, O.S.; Hewison, M.; Walker, L.S.K.; Lammas, D.A.; Raza, K.; Sansom, D.M. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and IL-2 Combine to Inhibit T Cell Production of Inflammatory Cytokines and Promote Development of Regulatory T Cells Expressing CTLA-4 and FoxP3. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 5458–5467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Etten, E.; Mathieu, C. Immunoregulation by 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3: Basic Concepts. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005, 97, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauretani, F.; Salvi, M.; Zucchini, I.; Testa, C.; Cattabiani, C.; Arisi, A.; Maggio, M. Relationship between Vitamin D and Immunity in Older People with COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirapongsananuruk, O.; Melamed, I.; Leung, D.Y.M. Additive Immunosuppressive Effects of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 and Corticosteroids on T(H)1, but Not T(H)2, Responses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000, 106, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Hazra, S.; Goswami, R. Calcitriol Impairs the Secretion of IL-4 and IL-13 in Th2 Cells via Modulating the VDR-Gata3-Gfi1 Axis. J. Immunol. 2024, 213, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staeva-Vieira, T.P.; Freedman, L.P. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Inhibits IFN-γ and IL-4 Levels During In Vitro Polarization of Primary Murine CD4+ T Cells. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauss, D.; Freiwald, T.; McGregor, R.; Yan, B.; Wang, L.; Nova-Lamperti, E.; Kumar, D.; Zhang, Z.; Teague, H.; West, E.E.; et al. Autocrine Vitamin D Signaling Switches off Pro-Inflammatory Programs of TH1 Cells. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimalawansa, S.J. Infections and Autoimmunity—The Immune System and Vitamin D: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassiou, L.; Kostoglou-Athanassiou, I.; Koutsilieris, M.; Shoenfeld, Y. Vitamin D and Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitamin D—Health Professional Fact Sheet. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Hahn, J.; Cook, N.R.; Alexander, E.K.; Friedman, S.; Walter, J.; Bubes, V.; Kotler, G.; Lee, I.M.; Manson, J.A.E.; Costenbader, K.H. Vitamin D and Marine Omega 3 Fatty Acid Supplementation and Incident Autoimmune Disease: VITAL Randomized Controlled Trial. BMJ 2022, 376, e066452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, D.A.; Walton, R.T.; Griffiths, C.J.; Martineau, A.R. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in the Vitamin D Pathway Associating with Circulating Concentrations of Vitamin D Metabolites and Non-Skeletal Health Outcomes: Review of Genetic Association Studies. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 164, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agliardi, C.; Guerini, F.R.; Bolognesi, E.; Zanzottera, M.; Clerici, M. VDR Gene Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Autoimmunity: A Narrative Review. Biology 2023, 12, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melake, A.; Mengstie, M.A. Vitamin D Deficiency and VDR TaqI Polymorphism on Diabetic Nephropathy Risk among Type 2 Diabetes Patients. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1567716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafentzi, T.; Tsounis, E.P.; Tourkochristou, E.; Avramopoulou, E.; Aggeletopoulou, I.; Geramoutsos, G.; Sotiropoulos, C.; Pastras, P.; Thomopoulos, K.; Theocharis, G.; et al. Genetic Polymorphisms (ApaI, FokI, BsmI, and TaqI) of the Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) Influence the Natural History and Phenotype of Crohn’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani, D.; Razi, B.; Motallebnezhad, M.; Rezaei, R. Association between Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) Polymorphisms and the Risk of Multiple Sclerosis (MS): An Updated Meta-Analysis. BMC Neurol. 2019, 19, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Azarnezhad, A.; Khanbabaei, H.; Izadpanah, E.; Abdollahzadeh, R.; Barreto, G.E.; Sahebkar, A. Vitamin D Receptor Genetic Polymorphisms and the Risk of Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Steroids 2020, 158, 108615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakosiński, M.; Żyła, M.; Kamieniak, A.; Kluz, N.; Gil-Kulik, P. Vitamin D Receptor Polymorphisms and Immunological Effects of Vitamin D in Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latini, A.; De Benedittis, G.; Perricone, C.; Colafrancesco, S.; Conigliaro, P.; Ceccarelli, F.; Chimenti, M.S.; Novelli, L.; Priori, R.; Conti, F.; et al. VDR Polymorphisms in Autoimmune Connective Tissue Diseases: Focus on Italian Population. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 5812136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, V.S.; Sharma, M.; Anbhule, A.P.; Jaison, A.; Info, A. Exploring Genetic Variability in VDR FokI and BsmI Polymorphisms and Their Association with Rheumatoid Arthritis. EJIFCC 2025, 36, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Song, G.G.; Bae, S.C.; Lee, Y.H. Vitamin D Receptor FokI, BsmI, and TaqI Polymorphisms and Susceptibility to Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Meta-Analysis. Z. Rheumatol. 2016, 75, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.B.; Jiang, Z.P.; Lin, Z.J.; Su, N. Association of Vitamin D Receptor Gene Polymorphism with the Risk of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2015, 35, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Du, S.; Zhao, L.; Jain, S.; Sahay, K.; Rizvanov, A.; Lezhnyova, V.; Khaibullin, T.; Martynova, E.; Khaiboullina, S.; et al. Autoreactive Lymphocytes in Multiple Sclerosis: Pathogenesis and Treatment Target. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 996469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasooriya, N.N.; Elliott, T.M.; Neale, R.E.; Vasquez, P.; Comans, T.; Gordon, L.G. The Association between Vitamin D Deficiency and Multiple Sclerosis: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 90, 105804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faridar, A.; Eskandari, G.; Sahraian, M.A.; Minagar, A.; Azimi, A. Vitamin D and Multiple Sclerosis: A Critical Review and Recommendations on Treatment. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2012, 112, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailike, B.; Onzhanova, Z.; Akbay, B.; Tokay, T.; Molnár, F. Vitamin D in Central Nervous System: Implications for Neurological Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kočovská, E.; Gaughran, F.; Krivoy, A.; Meier, U.C. Vitamin-D Deficiency as a Potential Environmental Risk Factor in Multiple Sclerosis, Schizophrenia, and Autism. Front. Psychiatry 2017, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, H.A.; Rasouli, J.; Ciric, B.; Wei, D.; Rostami, A.; Zhang, G.X. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Suppressed Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis through Both Immunomodulation and Oligodendrocyte Maturation. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2017, 102, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.R.C.; Mimura, L.A.N.; Fraga-Silva, T.F.d.C.; Ishikawa, L.L.W.; Fernandes, A.A.H.; Zorzella-Pezavento, S.F.G.; Sartori, A. Calcitriol Prevents Neuroinflammation and Reduces Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption and Local Macrophage/Microglia Activation. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassard, S.D.; Fitzgerald, K.C.; Qian, P.; Emrich, S.A.; Azevedo, C.J.; Goodman, A.D.; Sugar, E.A.; Pelletier, D.; Waubant, E.; Mowry, E.M. High-Dose Vitamin D3 Supplementation in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A Randomised Clinical Trial. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörr, J.; Bäcker-Koduah, P.; Wernecke, K.D.; Becker, E.; Hoffmann, F.; Faiss, J.; Brockmeier, B.; Hoffmann, O.; Anvari, K.; Wuerfel, J.; et al. High-Dose Vitamin D Supplementation in Multiple Sclerosis—Results from the Randomized EVIDIMS (Efficacy of Vitamin D Supplementation in Multiple Sclerosis) Trial. Mult. Scler. J. Exp. Transl. Clin. 2020, 6, 2055217320903474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Figueroa, E.; Moreno-Bernardino, C.; Bäcker-Koduah, P.; Dörr, J.; Rubarth, K.; Konietschke, F.; Bellmann-Strobl, J.; Ruprecht, K.; Oertel, F.C.; Paul, F.; et al. Neuroprotective Role of High Dose Vitamin D Supplementation in Multiple Sclerosis: Sub-Analysis of the EVIDIMS Trial. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2025, 101, 106567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thouvenot, E.; Laplaud, D.; Lebrun-Frenay, C.; Derache, N.; Le Page, E.; Maillart, E.; Froment-Tilikete, C.; Castelnovo, G.; Casez, O.; Coustans, M.; et al. High-Dose Vitamin D in Clinically Isolated Syndrome of Multiple Sclerosis The D-Lay MS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2025, 333, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camu, W.; Lehert, P.; Pierrot-Deseilligny, C.; Hautecoeur, P.; Besserve, A.; Deleglise, A.S.J.; Payet, M.; Thouvenot, E.; Souberbielle, J.C. Cholecalciferol in Relapsing-Remitting MS: A Randomized Clinical Trial (CHOLINE). Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 6, e597, Erratum in Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2019, 7, e648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hupperts, R.; Smolders, J.; Vieth, R.; Holmøy, T.; Marhardt, K.; Schluep, M.; Killestein, J.; Barkhof, F.; Beelke, M.; Grimaldi, L.M.E. Randomized Trial of Daily High-Dose Vitamin D3 in Patients with RRMS Receiving Subcutaneous Interferon β-1a. Neurology 2019, 93, e1906–e1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolders, J.; Hupperts, R.; Barkhof, F.; Grimaldi, L.M.E.; Holmoy, T.; Killestein, J.; Rieckmann, P.; Schluep, M.; Vieth, R.; Hostalek, U.; et al. Efficacy of Vitamin D3 as Add-on Therapy in Patients with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis Receiving Subcutaneous Interferon Beta-1a: A Phase II, Multicenter, Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Neurol. Sci. 2011, 311, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muris, A.H.; Smolders, J.; Rolf, L.; Thewissen, M.; Hupperts, R.; Damoiseaux, J. Immune Regulatory Effects of High Dose Vitamin D3 Supplementation in a Randomized Controlled Trial in Relapsing Remitting Multiple Sclerosis Patients Receiving IFNβ; the SOLARIUM Study. J. Neuroimmunol. 2016, 300, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M.V.; Schett, G.; Steffen, U. Autoantibodies in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Historical Background and Novel Findings. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 63, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinne, R.W.; Bräuer, R.; Stuhlmüller, B.; Palombo-Kinne, E.; Burmester, G.R. Macrophages in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2000, 2, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, L.L.W.; Colavite, P.M.; Fraga-Silva, T.F.d.C.; Mimura, L.A.N.; França, T.G.D.; Zorzella-Pezavento, S.F.G.; Chiuso-Minicucci, F.; Marcolino, L.D.; Penitenti, M.; Ikoma, M.R.V.; et al. Vitamin D Deficiency and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2017, 52, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neve, A.; Corrado, A.; Cantatore, F.P. Immunomodulatory Effects of Vitamin D in Peripheral Blood Monocyte-Derived Macrophages from Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 14, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwerina, K.; Baum, W.; Axmann, R.; Heiland, G.R.; Distler, J.H.; Smolen, J.; Hayer, S.; Zwerina, J.; Schett, G. Vitamin D Receptor Regulates TNF-Mediated Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.; Rasool, M. Genetics, Epigenetics and Autoimmunity Constitute a Bermuda Triangle for the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Life Sci. 2024, 357, 123075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Kwon, E.J.; Lee, J.J. Rheumatoid Arthritis: Pathogenic Roles of Diverse Immune Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.R.; Li, D.; Jeffery, L.E.; Raza, K.; Hewison, M. Vitamin D, Autoimmune Disease and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2020, 106, 58–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wei, W.; Yin, F.; Chen, M.; Ma, T.R.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, J.R.; Zheng, S.-G.; Han, J. The Abnormal Expression of CCR4 and CCR6 on Tregs in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 15043–15053. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery, L.E.; Raza, K.; Hewison, M. Vitamin D in Rheumatoid Arthritis—Towards Clinical Application. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.-Y.; Luo, J.; Li, X.-F.; Wei, D.-D.; Liu, Y. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D 3 Modulates T Cell Differentiation and Impacts on the Production of Cytokines from Chinese Han Patients with Early Rheumatoid Arthritis. Immunol. Res. 2019, 67, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Banna, H.S.; Gado, S.E. Vitamin D: Does It Help Tregs in Active Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Expert. Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 16, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Chaturvedi, V.; Ganguly, N.K.; Mittal, S.A. Vitamin D Deficiency: Concern for Rheumatoid Arthritis and COVID-19? Mol. Cell Biochem. 2021, 476, 4351–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, H. Impact of Vitamin D Deficiency on Clinical Parameters in Treatment-Naïve Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Z. Rheumatol. 2018, 77, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Liu, J.; Davies, M.L.; Chen, W. Serum Vitamin D Level and Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity: Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainaghi, P.P.; Bellan, M.; Antonini, G.; Bellomo, G.; Pirisi, M. Unsuppressed Parathyroid Hormone in Patients with Autoimmune/Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases: Implications for Vitamin D Supplementation. Rheumatology 2011, 50, 2290–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainaghi, P.P.; Bellan, M.; Nerviani, A.; Sola, D.; Molinari, R.; Cerutti, C.; Pirisi, M. Superiority of a High Loading Dose of Cholecalciferol to Correct Hypovitaminosis D in Patients with Inflammatory/Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases. J. Rheumatol. 2013, 40, 120536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, M.A.; Chaudhry, H.; Mushtaq, J.; Khan, O.S.; Babar, M.; Hashim, T.; Zeb, S.; Tariq, M.A.; Patlolla, S.R.; Ali, J.; et al. An Overview of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) Pathogenesis, Classification, and Management. Cureus 2022, 14, e30330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hile, G.A.; Coit, P.; Xu, B.; Victory, A.M.; Gharaee-Kermani, M.; Estadt, S.N.; Maz, M.P.; Martens, J.W.S.; Wasikowski, R.; Dobry, C.; et al. Regulation of Photosensitivity by the Hippo Pathway in Lupus Skin. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023, 75, 1216–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, J.F.; Skare, T.L.; Martinez, A.T.A.; Shoenfeld, Y. Anti-Vitamin D Antibodies. Autoimmun. Rev. 2025, 24, 103718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J.F.; Blank, M.; Kiss, E.; Tarr, T.; Amital, H.; Shoenfeld, Y. Anti-Vitamin D, Vitamin D in SLE. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1109, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaniv, G.; Twig, G.; Shor, D.B.A.; Furer, A.; Sherer, Y.; Mozes, O.; Komisar, O.; Slonimsky, E.; Klang, E.; Lotan, E.; et al. A Volcanic Explosion of Autoantibodies in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Diversity of 180 Different Antibodies Found in SLE Patients. Autoimmun. Rev. 2015, 14, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, S.; Chesney, R.W.; Hamstra, A.; Eisman, J.A.; O’Gorman, A.M.; Deluca, H.F. Reduced Serum 1,25-(OH)2 Vitamin D3 Levels in Prednisone-Treated Adolescents with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Acta Paediatr. 1979, 68, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breslin, L.C.; Magee, P.J.; Wallace, J.M.W.; McSorley, E.M. An Evaluation of Vitamin D Status in Individuals with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2011, 70, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, C.C.; Birmingham, D.J.; Ho, L.Y.; Hebert, L.A.; Song, H.; Rovin, B.H. Vitamin D Deficiency as Marker for Disease Activity and Damage in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Comparison with Anti-DsDNA and Anti-C1q. Lupus 2012, 21, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Yang, S.; Fan, S.; Tang, Y.; Teng, Y.; Tao, X.; Lu, W. Is Vitamin D Deficiency the Cause or the Effect of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Evidence from Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization Analysis. J. Immunol. Res. 2022, 2022, 8689777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Khandker, S.S.; Alam, S.S.; Kotyla, P.; Hassan, R. Vitamin D Status in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Autoimmun. Rev. 2019, 18, 102392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemire, J.M.; Ince, A.; Takashima, M. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Attenuates of Expression of Experimental Murine Lupus of MRL/1 Mice. Autoimmunity 1992, 12, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaisberg, M.W.; Kaneno, R.; Franco, M.F.; Mendes, N.F. Influence of Cholecalciferol (Vitamin D3) on the Course of Experimental Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in F1 (NZB×W) Mice. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2000, 14, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa Freitas, E.; Evelyn Karnopp, T.; de Souza Silva, J.M.; Cavalheiro do Espírito Santo, R.; da Rosa, T.H.; de Oliveira, M.S.; da Costa Gonçalves, F.; de Oliveira, F.H.; Guilherme Schaefer, P.; André Monticielo, O. Vitamin D Supplementation Ameliorates Arthritis but Does Not Alleviates Renal Injury in Pristane-Induced Lupus Model. Autoimmunity 2019, 52, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, N.; Lv, E.; Ci, C.; Li, X. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Ameliorates Lupus Nephritis through Inhibiting the NF-ΚB and MAPK Signalling Pathways in MRL/Lpr Mice. BMC Nephrol. 2022, 23, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; An, Q.; Ju, B.; Zhang, J.; Fan, P.; He, L.; Wang, L. Role of Vitamin D/VDR Nuclear Translocation in down-Regulation of NF-ΚB/NLRP3/Caspase-1 Axis in Lupus Nephritis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 100, 108131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, E.A.; Nguyen, J.K.; Liu, J.; Keller, E.; Campbell, N.; Zhang, C.J.; Smith, H.R.; Li, X.; Jørgensen, T.N. Low Levels of Vitamin D Promote Memory B Cells in Lupus. Nutrients 2020, 12, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, J.S.; Gui, M.; Zhang, H. Expression of Vitamin D Receptor in Renal Tissue of Lupus Nephritis and Its Association with Renal Injury Activity. Lupus 2019, 28, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Azevêdo Silva, J.; Fernandes, K.M.; Pancotto, J.A.T.; Fragoso, T.S.; Donadi, E.A.; Crovella, S.; Sandrin-Garcia, P. Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) Gene Polymorphisms and Susceptibility to Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Clinical Manifestations. Lupus 2013, 22, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Qiao, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, F.; Gao, C.; Duan, J.; Liang, L.; Di, X.; Yuan, Y.; Gao, Y.; et al. Vitamin D Protects Podocytes from Autoantibodies Induced Injury in Lupus Nephritis by Reducing Aberrant Autophagy. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linker-Israeli, M.; Elstner, E.; Klinenberg, J.R.; Wallace, D.J.; Koeffler, H.P. Vitamin D3 and Its Synthetic Analogs Inhibit the Spontaneous in Vitro Immunoglobulin Production by SLE-Derived PBMC. Clin. Immunol. 2001, 99, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritterhouse, L.L.; Crowe, S.R.; Niewold, T.B.; Kamen, D.L.; Macwana, S.R.; Roberts, V.C.; Dedeke, A.B.; Harley, J.B.; Scofield, R.H.; Guthridge, J.M.; et al. Vitamin D Deficiency Is Associated with an Increased Autoimmune Response in Healthy Individuals and in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 1569–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, I.G.A.; Clarke, A.J. B Cell Metabolism and Autophagy in Autoimmunity. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 681105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrier, B.; Derian, N.; Schoindre, Y.; Chaara, W.; Geri, G.; Zahr, N.; Mariampillai, K.; Rosenzwajg, M.; Carpentier, W.; Musset, L.; et al. Restoration of Regulatory and Effector T Cell Balance and B Cell Homeostasis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients through Vitamin D Supplementation. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012, 14, R221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, G.L.; Paupitz, J.; Aikawa, N.E.; Takayama, L.; Bonfa, E.; Pereira, R.M.R. Vitamin D Supplementation in Adolescents and Young Adults with Juvenile Systemic Lupus Erythematosus for Improvement in Disease Activity and Fatigue Scores: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2016, 68, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, G.L.; Paupitz, J.A.; Aikawa, N.E.; Alvarenga, J.C.; Pereira, R.M.R. A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial of Vitamin D Supplementation in Juvenile-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Positive Effect on Trabecular Microarchitecture Using HR-PQCT. Osteoporos. Int. 2018, 29, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranow, C.; Kamen, D.L.; Dall’Era, M.; Massarotti, E.M.; MacKay, M.C.; Koumpouras, F.; Coca, A.; Chatham, W.W.; Clowse, M.E.B.; Criscione-Schreiber, L.G.; et al. Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of the Effect of Vitamin D3 on the Interferon Signature in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015, 67, 1848–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinho, A.; Carvalho, C.; Boleixa, D.; Bettencourt, A.; Leal, B.; Guimarães, J.; Neves, E.; Oliveira, J.C.; Almeida, I.; Farinha, F.; et al. Vitamin D Supplementation Effects on FoxP3 Expression in T Cells and FoxP3+/IL-17A Ratio and Clinical Course in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients: A Study in a Portuguese Cohort. Immunol. Res. 2017, 65, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.W.; Kim, H.A.; Suh, C.H.; Jung, J.Y. Sex Hormones Affect the Pathogenesis and Clinical Characteristics of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Front Med. 2022, 9, 906475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajec, A.; Trebušak Podkrajšek, K.; Tesovnik, T.; Šket, R.; Čugalj Kern, B.; Jenko Bizjan, B.; Šmigoc Schweiger, D.; Battelino, T.; Kovač, J. Pathogenesis of Type 1 Diabetes: Established Facts and New Insights. Genes 2022, 13, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulietti, A.; Gysemans, C.; Stoffels, K.; Van Etten, E.; Decallonne, B.; Overbergh, L.; Bouillon, R.; Mathieu, C. Vitamin D Deficiency in Early Life Accelerates Type 1 Diabetes in Non-Obese Diabetic Mice. Diabetologia 2004, 47, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Liu, X.; Cai, X.; Zou, F. Vitamin D Supplementation Induces CatG-Mediated CD4þ T Cell Inactivation and Restores Pancreatic b-Cell Function in Mice with Type 1 Diabetes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2022, 322, E74–E84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, P.J.; Centelles-Lodeiro, J.; Ellis, D.; Cook, D.P.; Sassi, G.; Verlinden, L.; Verstuyf, A.; Raes, J.; Mathieu, C.; Gysemans, C. High Serum Vitamin D Concentrations, Induced via Diet, Trigger Immune and Intestinal Microbiota Alterations Leading to Type 1 Diabetes Protection in NOD Mice. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 902678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Li, X.; Liu, B.; Huang, J.; Xiang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, G.; Xie, Z.; et al. Combination Therapy with Saxagliptin and Vitamin D for the Preservation of β-Cell Function in Adult-Onset Type 1 Diabetes: A Multi-Center, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, J.; Sumnik, Z.; Pelikanova, T.; Chavez, L.N.; Lundberg, E.; Rica, I.; Martínez-Brocca, M.A.; de Adana, M.R.; Wahlberg, J.; Katsarou, A.; et al. Intralymphatic Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase with Vitamin d Supplementation in Recent-Onset Type 1 Diabetes: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase IIb Trial. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 1604–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo Moreira, C.F.; Ferreira Peres, W.A.; Silva do Nascimento Braga, J.; Proença da Fonseca, A.C.; Junior, M.C.; Luescher, J.; Campos, L.; de Carvalho Padilha, P. Effect of Vitamin D Supplementation on Glycemic Control in Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: Data from a Controlled Clinical Trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2025, 224, 112210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbay, M.A.L.; Sato, M.N.; Finazzo, C.; Duarte, A.J.S.; Dib, S.A. Effect of Cholecalciferol as Adjunctive Therapy with Insulin on Protective Immunologic Profile and Decline of Residual β-Cell Function in New-Onset Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2012, 166, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiber, G.; Prietl, B.; Fröhlich-Reiterer, E.; Lechner, E.; Ribitsch, A.; Fritsch, M.; Rami-Merhar, B.; Steigleder-Schweiger, C.; Graninger, W.; Borkenstein, M.; et al. Cholecalciferol Supplementation Improves Suppressive Capacity of Regulatory T-Cells in Young Patients with New-Onset Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus—A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Immunol. 2015, 161, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savastio, S.; Cadario, F.; Genoni, G.; Bellomo, G.; Bagnati, M.; Secco, G.; Picchi, R.; Giglione, E.; Bona, G. Vitamin D Deficiency and Glycemic Status in Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, V.; White, J.H. Species-Specific Regulation of Innate Immunity by Vitamin D Signaling. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 164, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcinkowska, E. The Vitamin D System in Humans and Mice: Similar but Not the Same. Reports 2020, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council (US) Subcommittee on Laboratory Animal Nutrition. Nutrient Requirements of Laboratory Animals, 4th ed.; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Recommended intakes for vitamin D. In Vitamin and Mineral Requirements in Human Nutrition, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Bangkok, Thailand, 2004; pp. 53–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, J.; Bishop, E.L.; Harrison, S.R.; Swift, A.; Cooper, S.C.; Dimeloe, S.K.; Raza, K.; Hewison, M. Autoimmune Disease and Interconnections with Vitamin D. Endocr Connect. 2022, 11, e210554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Trial Name | Trial Design | Study Population | Treatment | Primary Endpoint | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIDAMS (NCT01490502) [72] | Randomized, phase 3, double-blind, multicenter, controlled trial. | 172 relapsing- remitting MS (RRMS) patients. | 600 IU/day (low dose) or 5000 IU/day (high dose) cholecalciferol as an add-on of glatiramer acetate daily. | Clinical relapse at 96 weeks 1. | No difference in relapse rate was found among patients receiving either low-dose or high-dose supplementation. |

| EVIDIMS (NCT01440062) [73,74] | Multicenter randomized, double-blind, phase 2a trial. | 53 patients with RRMS or clinically isolated syndrome (CIS). | 20,400 IU or 400 IU cholecalciferol every other day for 18 months as an add-on of IFN β-1b. | Number of new T2-weighted (T2w) hyperintense lesions on brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) at month 18. | No significant differences in the number of T2w lesions were detected between high- or low-dose supplementation groups. |

| D-Lay-MS (NCT01817166) [75] | Randomized phase 3 placebo- controlled clinical trial. | 303 patients with CIS suggesting MS or RRMS. | 100,000 IU cholecalciferol (n = 156) or placebo (n = 147) every two weeks for 24 months. | Measure of disease activity over 24 months of follow-up 2. | Cholecalciferol reduces disease activity in CIS and early RRMS. |

| CHOLINE (NCT01198132) [76] | Phase II, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled parallel-group trial. | 90 RRMS patients. | 7143 IU/day of cholecalciferol or placebo for 96 weeks. | Reduction in annualized relapse rate (ARR) 3. | Cholecalciferol supplementation significantly reduces ARR. |

| SOLAR (NCT01285401) [77] | Phase II, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo- controlled trial. | 186 patients with RRMS. | Placebo or 6670 IU/day cholecalciferol for 4 weeks followed by 14,007 IU/day up to week 48 as an add-on to IFN β-1a. | Proportion of patients with No Evidence of Disease Activity-3 (NEDA-3), Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) progression, or Combined Unique Active (CUA) lesions at week 48 4. | Cholecalciferol supplementation to IFN β-1a does not provide an additional effect on NEDA-3. High dose of cholecalciferol significantly reduces the number of CUA lesions, but no significant differences were found in the proportion of relapse-free patients or EDSS progression at 48 weeks. |

| Authors and Year | Study Design | Endpoint | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lemire J.M. et al., 1992 [107] | 5 Murphy Roths Large/ lymphoproliferation (MRL/lpr) female mice injected with 0.1 μg calcitriol every other day for 4 weeks and then 0.15 μg for 18 weeks; 5 MRL/lpr mice in the control group received placebo. | Determination of the effects of calcitriol on proteinuria and antinuclear antibody production 1. | Calcitriol treatment reduces proteinuria degree and autoantibody titer. |

| Vaisberg M.W. et al., 2000 [108] | 22 females (F) and 20 males (M) New Zealand Black × New Zealand White F1 (F1 NZB × W) mice injected with 10 μg (6 F, 5 M) or 3 μg (5 F, 5 M) cholecalciferol or placebo (11 F, 10 M) once a week for 7 months. | Evaluation of the effects of cholecalciferol treatment on kidney histology 2. | Cholecalciferol worsens renal histology in female mice compared to control. No significant differences were observed among males. |

| Freitas E.C. et al., 2019 [109] | 28 female Bagg’s Albino (BALB)/c mice randomized as control group (n = 8), pristane- induced lupus (PIL, n = 10) group, or PIL injected with 2 μg/kg/day of calcitriol every two days for 6 months (n = 10). | Detection of immunoglobulin (Ig)G and IgM in renal tissue and histopathological evaluation. Determination of the effects of calcitriol supplementation on pristane-induced SLE-associated arthritis 3. | Calcitriol does not reduce renal injury or antibody deposition. However, it reduces synovial inflammation and arthritis development. |

| Li X. et al., 2022 [110] | 48 MRL/lpr female mice injected with 4 μg/kg calcitriol twice a week for 3 weeks or placebo for 3 weeks. | Evaluation of calcitriol’s effects on kidney histology, C1q, C3, IgG and IgM deposition, NF-κB and MAPK levels, and urine protein concentration 4. | Calcitriol treatment ameliorates renal damage and decreases proteinuria, as well as IgM, IgG, C1q and C3 deposition. Calcitriol downregulates NF-κB and MAPK signaling, reducing inflammation and ameliorating LN. |

| Huang J. et al., 2021 [111] | Female MRL/lpr mice injected with 300 ng/kg paricalcitol 5 times a week for 8 weeks. Black 6 (C57BL/6) mice were used as control group and injected with placebo. Mouse Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells (mRTECs) were used to define the molecular mechanisms of paricalcitol. | Evaluation of the effects of paricalcitol on LN and molecular pathways involved 5. | Paricalcitol reduces proteinuria and anti-dsDNA antibodies and alleviates LN. Paricalcitol reverses anti-dsDNA antibody-induced apoptosis through the modulation of NFκB/NLRP3/caspase-1/ IL-1β/IL-18 axis in mRTECs. |

| Yamamoto E. et al., 2020 [112] | 15 Act1−/− mice were fed with 0 IU/kg (low), 2 IU/kg (normal), or 10 IU/kg (high) of cholecalciferol for 9 weeks. | Effects of cholecalciferol on the development of SLE-like characteristics 6. | Cholecalciferol restriction promotes memory B cell development and production of autoantibodies and immunoglobulins. |

| Authors and Year | Study Design | Methods | Endpoint | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun J. et al., 2019 [113] | Observational | Kidney biopsies from 20 patients with LN and 5 controls 1. | Evaluation of VDR expression in relation to renal histology, activity scores, and proteinuria. | Renal tissue from LN patients exhibited lower VDR expression compared to controls. VDR expression was inversely correlated with both the activity index and the severity of renal injury. |

| De Azevêdo Silva, et al., 2013 [114] | Observational | DNA extracted using salting out from whole blood of 158 SLE patients 2. | Assessment of the relationship between VDR polymorphisms and risk of SLE development. | No association between VDR SNPs with SLE susceptibility has been found. VDR polymorphisms have been associated with cutaneous and immunological alterations, arthritis, anti-dsDNA antibodies, nephritic disorders, and photosensitivity. |

| Yu Q. et al., 2019 [115] | Ex vivo | Immortalized human podocytes (HPCs) stimulated with IgG isolated from LN patients in presence or absence of 100 nM calcitriol 3. | Determination of the effects of calcitriol treatment on podocyte injury. | IgG from LN patients induces podocyte injury in HPCs, which is alleviated by treatment with calcitriol. |

| Observational | Renal biopsies and serum samples from 25 LN patients and 7 controls were used to determine autophagy and calcidiol levels 4. | Evaluation of the relationship between circulating calcidiol levels and number of autophagosomes in renal biopsies. | Autophagy is activated in renal tissue of LN patients, and it is correlated with calcidiol levels. | |

| Linker-Israeli M. et al., 2001 [116] | Ex vivo | PBMCs isolated from 65 female SLE patients and matched healthy controls 5. | Evaluation of the effects of calcitriol and other synthetic analogues on cell phenotype, proliferation, and IgG production. | Calcitriol and synthetic analogues reduce proliferation and IgG production and induce B cell apoptosis. |

| Ritterhouse L. et al., 2011 [117] | Observational | Serum samples and PBMCs of 32 female SLE patients and matched controls 6. | Evaluation of the relationship between calcidiol levels, B cell hyperactivity, and autoantibody production. | Low levels of calcidiol are related with increased B cell activation. |

| Trial Name | Trial Design | Study Population | Treatment | Primary Endpoint | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VITALUP (NCT01413230) [119] | Open-label single-arm prospective clinical trial. | 20 female SLE patients with hypovitaminosis D. No controls have been enrolled. | 100,000 IU/week for 4 weeks followed by 100,000 IU/month cholecalciferol for 6 months. Patients were evaluated at baseline, month 2, and month 6 after supplementation. | Immunological profile of B and T cells and gene expression profile of PBMCs 1. | Treatment reduces memory B cells and anti-dsDNA antibodies as well as Th1 and Th17 cells. |

| Cholecalciferol Supplementation on Disease Activity, Fatigue and Bone Mass on Juvenile SLE (NCT01892748) [120,121] | Randomized placebo- Controlled trial. | 40 female juvenile SLE patients. No controls have been enrolled. | Oral cholecalciferol at 50,000 IU/week or placebo for 6 months. | Effects of cholecalciferol supplementation on disease activity, fatigue, and bone mass 2. | Treatment significantly improves disease activity scores at 6 months compared to baseline, reduces fatigue at 6 months, and increases bone trabecular number at 6 months. |

| Vitamin D3 in SLE (NCT00710021) [122] | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled phase 2 study. | 48 SLE patients with stable disease. No controls have been enrolled. | 2000 IU (low dose), or 4000 IU (high dose) of oral cholecalciferol or placebo daily for 12 weeks. | Effects on expression of IFN-inducible genes 3. | No significant reduction in IFN signature has been reported in the supplemented groups. |

| Author and Year | Population and Intervention | Endpoint | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giulietti et al., 2004 [126] | 68 non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice fed with vitamin D-depleted diet vs. 69 control NOD mice fed with 2200 IU/kg/day vitamin D-supplemented diet for 100 days. From 100 days of age, mice were fed with supplemented diet until 250 days of age. | Investigation of the effects of vitamin D deficiency on T1D onset 1. | Vitamin D deficiency anticipates diabetes onset and increases severity. Increased CD4+ abd CD8+ cells and decreased Tregs infiltration have been reported in the thymus of female mice. |

| Lai X. et al., 2022 [127] | NOD mice were intraperitoneally injected with adenovirus carrying Cathepsin G (CatG) or Short-Hairpin RNA against CatG (sh-CatG) twice a week for 8 weeks. Mice were fed with 2200 IU/kg/day vitamin D-supplemented diet for 28 days. Control NOD mice were fed with diet containing the dietary requirements of vitamin D. | Investigation of the effects of vitamin D supplementation on CatG expression, CD4+ cell activation, and β cell function 2. | Vitamin D supplementation downregulates CatG expression, decreases CD4+ cell activation, improves β cell function, and inhibits apoptosis. |

| Martens P. et al., 2022 [128] | 93 female NOD mice were fed with either cholecalciferol-sufficient diet (control diet) or diet supplemented with 400 IU/day or 800 IU/day cholecalciferol until 25 weeks of age. | Evaluation of the effects of different doses of cholecalciferol supplementation on disease onset and immunological profile 3. | 800 IU/day supplementation decreases T1D development and increases FOXP3+ Tregs and IL-10-secreting CD4+ T cell frequency. |

| Study Design | Study Population and Treatment | Primary Endpoint | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective, multicenter, open-label, randomized. (ADVENT, NCT02407899) [129]. | 301 T1D patients randomized to (I) metformin with or without insulin (conventional therapy, CT, n = 99), (II) CT plus saxagliptin (n = 100), or (III) CT plus saxagliptin plus 2000 IU cholecalciferol/day (n = 102) for 24 months. | Evaluation of β cell function measured by C-peptide levels 1. | Improvement in β cell function loss between supplemented and conventional therapy groups, especially in patients with high Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase Autoantibody (GADA) levels. |

| Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled trial [130]. | 109 T1D patients received three intralymphatic injections with 4 μg Diamyd® on days 30, 60, and 90 and 2000 IU/day oral vitamin D for 4 months (n = 57) or placebo in place of each treatment (n = 52). Last study visit was performed at month 15. | Changes in serum C-peptide levels over the 2 h period after a mixed-meal tolerance test (MMTT) 2. | No differences in C-peptide levels between baseline and 15-month visit were reported. |

| Controlled clinical trial [131]. | 133 young T1D patients randomized to cholecalciferol at 2000 IU/day (n = 103) or placebo (n = 30) for 12 weeks. | Measurement of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) 3. | Minimal effects on glycemic control have been reported. |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled study [132]. | 35 new-onset T1D patients randomized to 2000 IU cholecalciferol (n = 17) or placebo (n = 18) for 18 months. | Evaluation of cytokines, chemokines, HbA1c, and C-peptide levels as well as Tregs frequency 4. | C-peptide levels increased at 12 months from diagnosis, and the decline was reduced at 18 months compared to controls. Increase in Tregs frequency was reported after 12 months. No differences in HbA1c levels have been identified. |

| Prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled trial (NCT01390480) [133]. | 30 juvenile T1D patients supplemented weekly with cholecalciferol (corresponding to 70 IU/kg/day) or placebo for 12 months. | Evaluation of changes in frequency and function of Tregs 5. | Tregs frequency did not differ between baseline and month 12. Suppressive function of Tregs increased at month 12. |

| Cross-sectional study [134]. | 141 juvenile T1D patients supplemented with 1000 IU/day cholecalciferol. | Evaluation of the effects of vitamin D supplementation on glycemic status 6. | Supplementation significantly increases serum calcidiol levels and reduces HbA1c at final visit. Calcidiol levels inversely correlate with insulin requirement. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Vincenzi, F.; Smirne, C.; Tonello, S.; Sainaghi, P.P. The Role of Vitamin D in Autoimmune Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010555

Vincenzi F, Smirne C, Tonello S, Sainaghi PP. The Role of Vitamin D in Autoimmune Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010555

Chicago/Turabian StyleVincenzi, Federica, Carlo Smirne, Stelvio Tonello, and Pier Paolo Sainaghi. 2026. "The Role of Vitamin D in Autoimmune Diseases" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010555

APA StyleVincenzi, F., Smirne, C., Tonello, S., & Sainaghi, P. P. (2026). The Role of Vitamin D in Autoimmune Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 555. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010555