Evaluating the Immunological Impact of Hepatitis B Vaccination in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Cohort Characteristics and Between-Group Comparisons

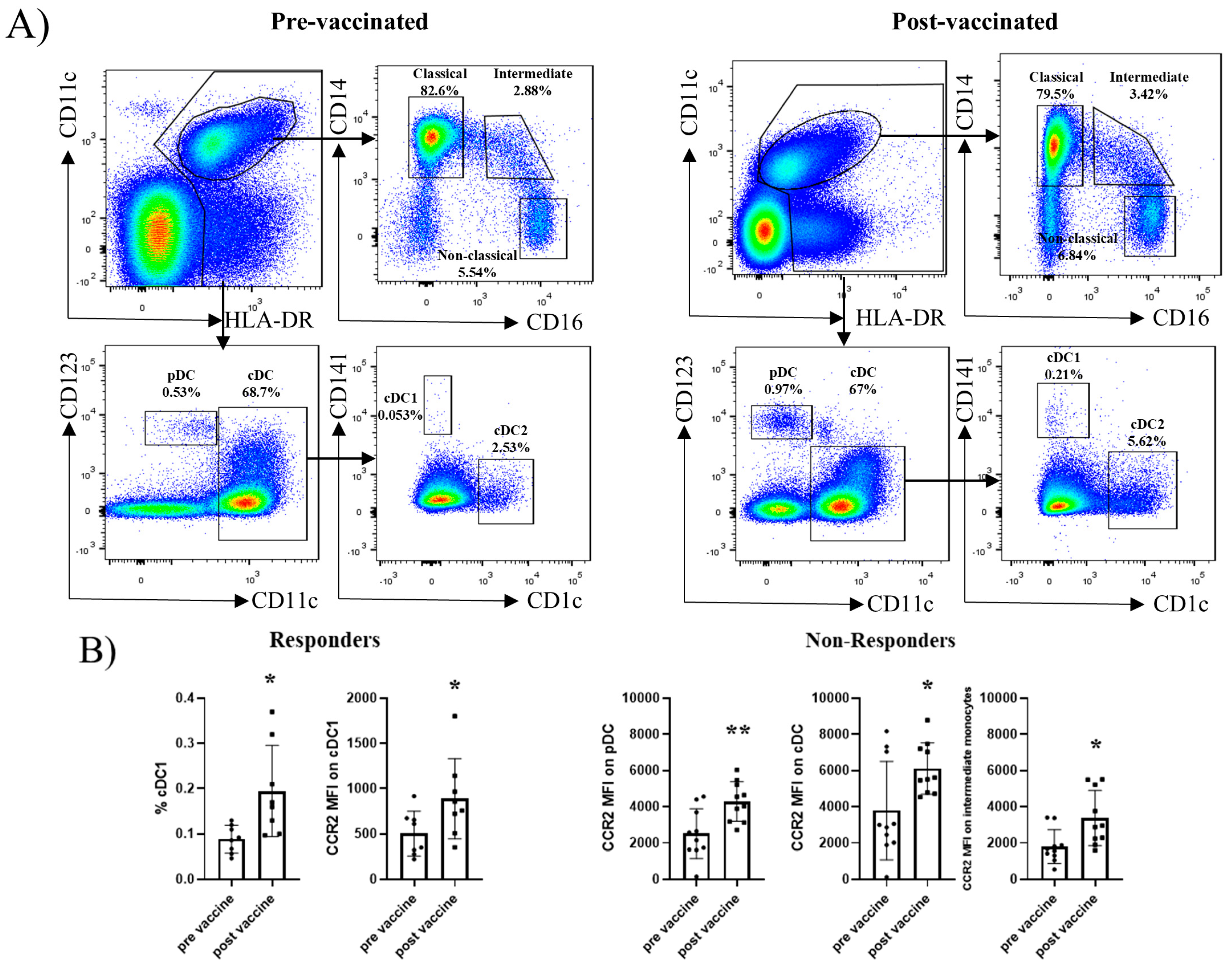

2.2. Dendritic Cell and Monocyte Subsets Do Not Differ Between Responders and Non-Responders at Baseline

2.3. B-Cell Subsets Differ Between Responders and Non-Responders Before and After Hbv Vaccination

2.4. T-Cell Subsets Differ Between Responders and Non-Responders Before and After Hbv Vaccination

2.5. Treg, Nk, and Nkt-Cell Subsets Differ Between Responders and Non-Responders After Hbv Vaccination

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients and Sample Collection

4.2. Blood Processing

4.3. Antibody Labelling

4.4. Flow Cytometry and Data Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| cDC | Conventional DC |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| FACs | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting |

| FMO | Fluorescence minus one |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HBsAg | Hepatitis B surface antigen |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HLA | Human leukocyte antigen |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| MFI | Mean fluorescence intensity |

| NK | Natural killer |

| NKT | Natural killer T cell |

| PBMC | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| pDC | Plasmacytoid DC |

| TEMRA | Terminal effector memory T cells |

| TNF | Tumour necrosis factor |

| Tregs | Regulatory T cell |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

References

- D’souza, S.; Lau, K.C.; Coffin, C.S.; Patel, T.R. Molecular mechanisms of viral hepatitis induced hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 5759–5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belle Jarvis, S.; Fenton-Lee, T.; Small, S. Introduction of the Hepatitis B Vaccine—Birth Dose: Methods of Improving Rates in a Milieu of Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccines 2023, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavanchy, D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J. Viral Hepat. 2004, 11, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, J.P.; Chaparro, M.; Esteve, M. Review article: Prevention and management of hepatitis B and C infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteve, M. Chronic hepatitis B reactivation following infliximab therapy in Crohn’s disease patients: Need for primary prophylaxis. Gut 2004, 53, 1363–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, G.; Navarra, G.; Mondello, S.; Costantino, L.; Colloredo, G.; Cucinotta, E.; Di Vita, G.; Scisca, C.; Squadrito, G.; Pollicino, T. Occult hepatitis B virus in liver tissue of individuals without hepatic disease. J. Hepatol. 2008, 48, 743–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharzik, T.; Ellul, P.; Greuter, T.; Rahier, J.F.; Verstockt, B.; Abreu, C.; Albuquerque, A.; Allocca, M.; Esteve, M.; Farraye, F.A.; et al. ECCO Guidelines on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Infections in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2021, 15, 879–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lello, F.A.; Martínez, A.P.; Flichman, D.M. Insights into induction of the immune response by the hepatitis B vaccine. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 4249–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.K.; Jena, A.; Mahajan, G.; Mohindra, R.; Suri, V.; Sharma, V. Meta-analysis: Hepatitis B vaccination in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 55, 908–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, J.A.; Habash, N.W.; Ismail, Y.A.; Tremaine, W.J.; Weaver, A.L.; Murray, J.A.; Loftus, E.V.; Absah, I. Effectiveness of Hepatitis B Vaccination for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel and Celiac Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 21, 2901–2907.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, J.P.; Menchén, L.; García-Sánchez, V.; Marín, I.; Villagrasa, J.R.; Chaparro, M. Comparison of the effectiveness of two protocols for vaccination (standard and double dosage) against hepatitis B virus in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 35, 1379–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro, M.; Gordillo, J.; Domènech, E.; Esteve, M.; Acosta, M.B.-D.; Villoria, A.; Iglesias-Flores, E.; Blasi, M.; Naves, J.E.; Benítez, O.; et al. Fendrix vs Engerix-B for Primo-Vaccination Against Hepatitis B Infection in Patients with Inflammatory Bowwithisease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, J.P.; Villagrasa, J.R.; Rodríguez-Nogueiras, A.; Chaparro, M. Efficacy of Hepatitis B Vaccination and Revaccination and Factors Impacting on Response in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 107, 1460–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, P.; Santos-Antunes, J.; Rodrigues, S.; Lopes, S.; Macedo, G. Treatment with infliximab or azathioprine negatively impact the efficacy of hepatitis B vaccine in inflammatory bowel disease patients. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 30, 1591–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, D.; Xu, A.-T.; Shen, J.; Ran, Z.-H. Effects of Immunosuppressants on Immune Response to Vaccine in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Chin. Med. J. 2015, 128, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cekic, C.; Aslan, F.; Kirci, A.; Gümüs, Z.Z.; Arabul, M.; Yüksel, E.S.; Vatansever, S.; Yurtsever, S.G.; Alper, E.; Ünsal, B. Evaluation of Factors Associated with Response to Hepatitis B Vaccination in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Medicine 2015, 94, e940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín, A.C. Immunogenicity and mechanisms impairing the response to vaccines in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 11273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaine Hollinger, F. Factors influencing the immune response to hepatitis B vaccine, booster dose guidelines, and vaccine protocol recommendations. Am. J. Med. 1989, 87, S36–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcay, I.M.; Katrinli, S.; Ozdil, K.; Doganay, G.D.; Doganay, L. Host genetic factors affecting hepatitis B infection outcomes: Insights from genome-wide association studies. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 3347–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Zhang, P.; Liu, M.; Zeng, W.; Yang, J.; Liu, H. Deltex1 Polymorphisms Are Associated with Hepatitis B Vaccination Non-Response in Southwest China. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chedid, M.G.; Deulofeut, H.; Yunis, D.E.; Lara-Marquez, M.L.; Salazar, M.; Deulofeut, R.; Awdeh, Z.; Alper, C.A.; Yunis, E.J. Defect in Th1-Like Cells of Nonresponders to Hepatitis B Vaccine. Hum. Immunol. 1997, 58, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrgozar, M.A.; Shokri, F. Enumeration of hepatitis B surface antigen-specific B lymphocytes in responder and non-responder normal individuals vaccinated with recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen. Immunology 2001, 104, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weihrauch, M.R.; von Bergwelt-Baildon, M.; Kandic, M.; Weskott, M.; Klamp, W.; Rösler, J.; Schultze, J.L. T cell responses to hepatitis B surface antigen are detectable in non-vaccinated individuals. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Li, M.; Ma, X.; Lin, J.; Li, D. CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells Protect the Proinflammatory Activation of Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 2621–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Yamauchi, K.; Kuwata, T.; Hayashi, N. Characterization of hepatitis B virus surface antigen-specific CD4+ T cells in hepatitis B vaccine non-responders. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2001, 16, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisicaro, P.; Rossi, M.; Vecchi, A.; Acerbi, G.; Barili, V.; Laccabue, D.; Montali, I.; Zecca, A.; Penna, A.; Missale, G.; et al. The Good and the Bad of Natural Killer Cells in Virus Control: Perspective for Anti-HBV Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.Q.; Moorman, J.P. Immune Exhaustion and Immune Senescence: Two Distinct Pathways for HBV Vaccine Failure During HCV and/or HIV Infection. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2013, 61, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, F.; Taskapan, H. Good response to HBsAg vaccine in dialysis patients is associated with high CD4+/CD8+ ratio. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2012, 44, 1501–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, W.; Xu, X.; Jiang, Q.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yu, W.; Shi, B.; Wan, S.; Liu, J.; et al. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen drives T cell immunity through non-canonical antigen presentation in mice. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, S.; Ren, L.; Chen, P.; Wang, M.; Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H. Functional Roles of Chemokine Receptor CCR2 and Its Ligands in Liver Disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 812431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Su, Z.; Yin, Y.; Li, J.; Wei, Q. Calcineurin B subunit triggers innate immunity and acts as a novel Engerix-B® HBV vaccine adjuvant. Vaccine 2012, 30, 4719–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.-H.; Lim, S.-G. CpG-Adjuvanted Hepatitis B Vaccine (HEPLISAV-B®) Update. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2021, 20, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Liu, L.; Yang, D.; Fu, S.; Bian, Y.; Sun, Z.; He, J.; Su, L.; Zhang, L.; Peng, H.; et al. Clearing Persistent Extracellular Antigen of Hepatitis B Virus: An Immunomodulatory Strategy To Reverse Tolerance for an Effective Therapeutic Vaccination. J. Immunol. 2016, 196, 3079–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnell, A.; Schwarz, B.; Wahlbuhl, M.; Allabauer, I.; Hess, M.; Weber, S.; Werner, F.; Schmidt, H.; Rechenauer, T.; Siebenlist, G.; et al. Distribution and Cytokine Profile of Peripheral B Cell Subsets Is Perturbed in Pediatric IBD and Partially Restored During a Successful IFX Therapy. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Dopico, T.; Colombel, J.-F.; Mehandru, S. Targeting B cells for inflammatory bowel disease treatment: Back to the future. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2020, 55, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, R.; Mohamed, Z.A.Z.; Abdallah, A.M. Relationship between Th1 and Th2 cytokine serum levels and immune response to Hepatitis B vaccination among Egyptian health care workers. J. Immunoassay Immunochem. 2018, 39, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Brunner, L.; Oz, E.A.; Sacherl, J.; Frank, G.; Kerth, H.A.; Thiele, F.; Wiegand, M.; Mogler, C.; Aguilar, J.C.; et al. Activation of CD4 T cells during prime immunization determines the success of a therapeutic hepatitis B vaccine in HBV-carrier mouse models. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallmer, K.; Oxenius, A. Recognition and Regulation of T Cells by NK Cells. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M.F.; Wolint, P.; Schwarz, K.; Jäger, P.; Oxenius, A. Functional Properties and Lineage Relationship of CD8+ T Cell Subsets Identified by Expression of IL-7 Receptor α and CD62L. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 4686–4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huster, K.M.; Busch, V.; Schiemann, M.; Linkemann, K.; Kerksiek, K.M.; Wagner, H.; Busch, D.H. Selective expression of IL-7 receptor on memory T cells identifies early CD40L-dependent generation of distinct CD8+ memory T cell subsets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 5610–5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M.F.; Beerli, R.R.; Agnellini, P.; Wolint, P.; Schwarz, K.; Oxenius, A. Long-lived memory CD8+ T cells are programmed by prolonged antigen exposure and low levels of cellular activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006, 36, 842–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boer, M.C.; Joosten, S.A.; Ottenhoff, T.H.M. Regulatory T-Cells at the Interface between Human Host and Pathogens in Infectious Diseases and Vaccination. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Responder Status | Sex | Age (year) | Smoking | BMI | Comorbidities | IBD Type | Location | IHB or Partial mayo pre-Vaccination | Year of Diagnostic | Current Treatment | Anti-HBs titer (IU/L, Prost-Vaccination) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAC01 | non-responder | Male | 70 | Former | 33.1 | Hypothyroidism | Crohn’s disease | Ileal | 0 | 2016 | Levothyroxine | N/A |

| VAC02 | non-responder | Male | 60 | Current | 23.5 | - | Ulcerative colitis | Extensive colitis | 0 | 2005 | Azathioprine | 148 |

| VAC03 | non-responder | Female | 55 | Former | 17.8 | Hypothyroidism | Ulcerative colitis | Extensive colitis | 0 | 2017 | mesalazine, carbimazole | N/A |

| VAC04 | non-responder | Male | 73 | Former | 28.4 | Benignprostatic hyperplasia | Crohn’s disease | Ileal | 0 | 2017 | Tamsulosine | N/A |

| VAC05 | non-responder | Female | 52 | Current | 24.5 | - | Crohn’s disease | Ileocolic | 0 | 2015 | Azathioprine | N/A |

| VAC06 | non-responder | Male | 52 | Never | 20.3 | - | Ulcerative colitis | Proctosigmoiditis | 1 | 2013 | Pentase | 57 |

| VAC07 | non-responder | Male | 41 | Never | 25.1 | - | Ulcerative colitis | Extensive colitis | 5 | 2018 | Pentase | 45 |

| VAC08 | non-responder | Female | 50 | Current | 21 | - | Crohn’s disease | Ileocolic | 0 | 2019 | - | 67 |

| VAC09 | non-responder | Female | 58 | Current | 25.5 | - | Crohn’s disease | Ileocolic | 0 | 2000 | Azathioprine | N/A |

| VAC10 | non-responder | Female | 72 | Former | 29.4 | Bronchial asthma | Ulcerative colitis | Left colitis | 4 | 2019 | Pentase | 33 |

| VAC11 | responder | Female | 45 | Never | 22.3 | Rosacea | Ulcerative colitis | Extensive colitis | 0 | 2014 | Azathioprine | >1000 |

| VAC12 | responder | Female | 70 | Current | 24.5 | Hypercholesterolemia | Ulcerative colitis | Extensive colitis | 0 | 2007 | Pentase | >1000 |

| VAC13 | responder | Male | 49 | Never | 23.5 | - | Ulcerative colitis | Extensive colitis | 0 | 2004 | Mesalazine | >1000 |

| VAC14 | responder | Male | 49 | Never | 24.3 | - | Ulcerative colitis | Left colitis | 0 | 1995 | Pentase | >1000 |

| VAC15 | responder | Female | 62 | Former | 16.3 | - | Ulcerative colitis | Extensive colitis | 1 | 2018 | Mesalazine | >1000 |

| VAC16 | responder | Male | 62 | Never | 22.4 | Crohn’s disease | Ileocolic | 0 | 2000 | Azathioprine | 389.34 | |

| VAC17 | responder | Female | 60 | Never | 21.5 | - | Crohn’s disease | Ileal | 0 | 2018 | Azathioprine | >1000 |

| VAC18 | responder | Male | 65 | Former | 33.9 | Diabetes mellitus, hepatic steatosis | Crohn’s disease | Ileal | 0 | 2018 | Metformin | >1000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Soleto, I.; Marin, A.C.; Baldan-Martin, M.; Bernardo, D.; Chaparro, M.; Gisbert, J.P. Evaluating the Immunological Impact of Hepatitis B Vaccination in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010531

Soleto I, Marin AC, Baldan-Martin M, Bernardo D, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Evaluating the Immunological Impact of Hepatitis B Vaccination in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010531

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoleto, Irene, Alicia C. Marin, Montse Baldan-Martin, David Bernardo, María Chaparro, and Javier P. Gisbert. 2026. "Evaluating the Immunological Impact of Hepatitis B Vaccination in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010531

APA StyleSoleto, I., Marin, A. C., Baldan-Martin, M., Bernardo, D., Chaparro, M., & Gisbert, J. P. (2026). Evaluating the Immunological Impact of Hepatitis B Vaccination in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 531. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010531