Dormancy Versus Germination: 3D Protein Modeling and Evolutionary Analyses Define the Roles of Genetic Variants in the Barley MKK3 Enzyme

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

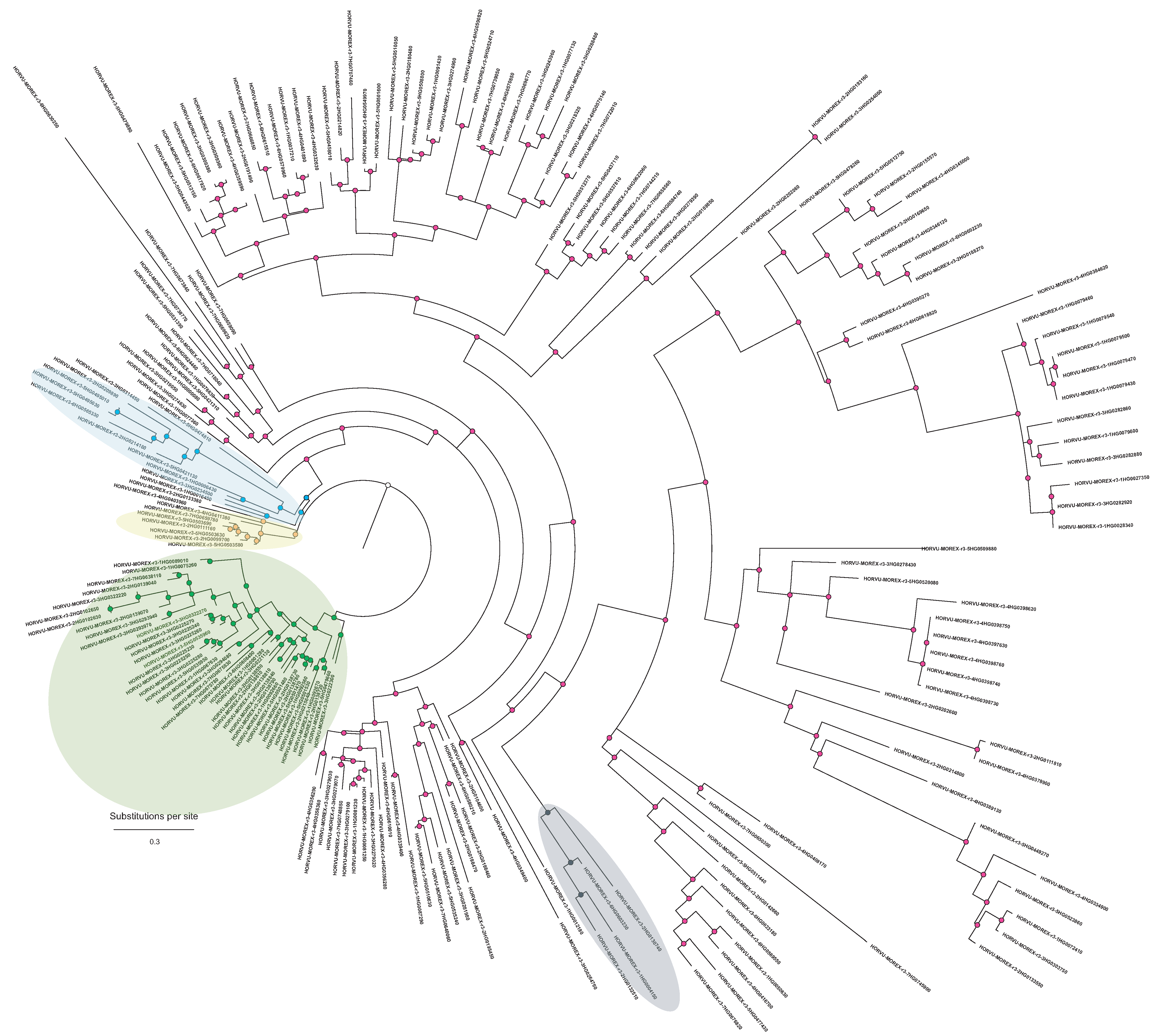

2.1. Phylogeny of MAPKs and Codon Selection

2.2. Ancestral Origin of Genetic Variants E165Q and T260N

2.3. Phosphorylation Sites of MKK3 and MAPK

2.4. Docking of Activated MKK3 with MAPK

2.5. All-Atom Structural Dynamics of HvMKK3/HvMPAK Model Complexes

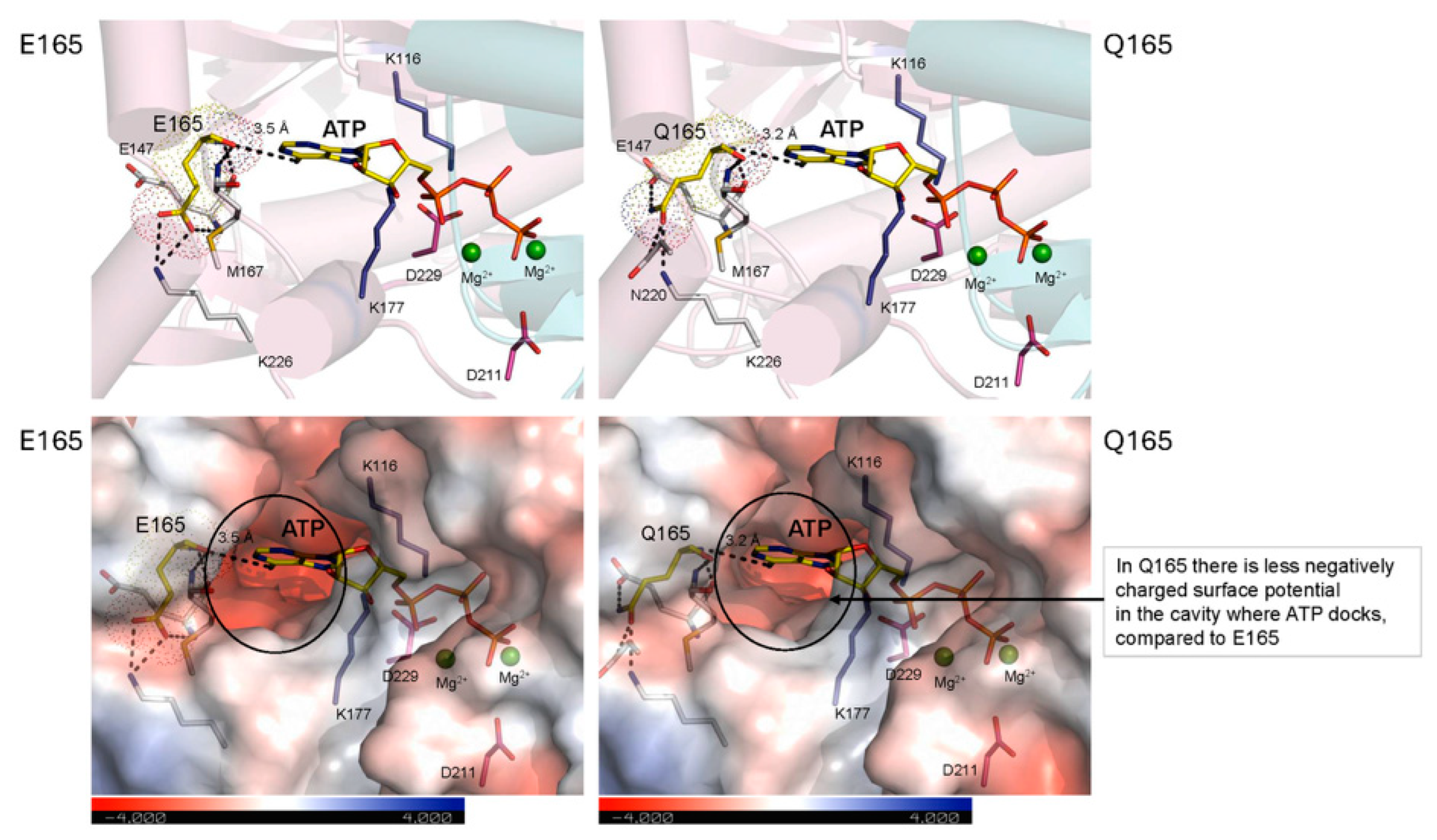

2.6. Effects of the E165Q Genetic Variant on MKK3 Structure

2.7. Effects of the N260T Genetic Variant on MKK3 Structure

2.8. Effects of Other Common MKK3 Variants

2.9. Mechanism of MKK3 Action: A Working Model

2.10. Are Dormancy, Germination, and Carbon/Nitrogen Metabolism Linked?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Computational Methods

3.2. Phylogeny of the MKK3 Enzyme

3.3. Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction

3.4. Selection Pressure on the N260T Variant

3.5. E165Q and N260T Rotameric Conformers

3.6. Identification of Phosphorylation Sites

4. Summary

- the number of MAPK genes in the barley genome and their phylogeny;

- the ancestral origin and phylogeny of the common genetic variants E165Q and T260N, which showed that the wild-type variants were most likely E165 and T260, respectively;

- the phosphorylation sites of the HvMKK3 enzyme (TFVGTVTY; T245-Y252; phosphorylatable Thr residues underlined) and the HvMAPK enzyme (SLKGTPY; S163-Y169; phosphorylatable residues underlined) and the likely phosphorylated amino acid residues therein;

- the theoretical molecular docking structure of the HvMKK3/HvMAPK complex and its dynamics;

- amino acid residues that are likely to be involved in ATP hydrolysis, and the need for the released phosphate group to diffuse through the enzyme to its target phosphorylation loop of the HvMAPK enzyme;

- the effects of the key genetic variants E165QE and T260N, made possible by a computational model of the enzyme–substrate complex that allowed the rationalization of the effects of electrostatic surface potentials and overall enzyme flexibility provided by the variants on HvMKK3 activity, which occur both at the ATP binding site (E165Q) and at the phosphorylated loops (T260N);

- a possible explanation of the effects of other common amino acid substitutions (A79V, G350R, N383D) on HvMKK3 activity.

5. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Bewley, J.D.; Black, M. Seeds: Physiology of Development and Germination; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Han, F.; Ullrich, S.E.; Clancy, J.A.; Jitkov, V.; Kilian, A.; Romagosa, I. Verification of barley seed dormancy loci via linked molecular markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1996, 92, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, S.M.; Rydel, T.J.; McClerren, A.L.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.Y.; Sturman, E.J.; Halls, C.; Chen, S.; Zeng, J.; Peng, J.; et al. The enzymology of alanine aminotransferase (AlaAT) isoforms from Hordeum vulgare and other organisms, and the HvAlaAT crystal structure. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012, 528, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Yamane, M.; Yamaji, N.; Kanamori, H.; Tagiri, A.; Schwerdt, J.G.; Fincher, G.B.; Matsumoto, T.; Takeda, K.; Komatsuda, T. Alanine aminotransferase controls seed dormancy in barley. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, S.; Pourkheirandish, M.; Morishige, H.; Kubo, Y.; Nakamura, M.; Ichimura, K.; Seo, S.; Kanamori, H.; Wu, J.; Ando, T.; et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3 regulates seed dormancy in barley. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, M.T.; Vequaud, D.; Wang, Y.; Andersen, C.B.; Bayer, M.; Box, A.; Braune, K.B.; Cai, Y.; Chen, F.; Cuesta-Seijo, J.A.; et al. Post-domestication selection of MKK3 shaped seed dormancy and end-use traits in barley. Science 2026, 391, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigeard, J.; Hirt, H. Nuclear signaling of plant MAPKs. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otani, M.; Tojo, R.; Regnard, S.; Zheng, L.; Hoshi, T.; Ohmori, S.; Tachibana, N.; Sano, T.; Koshimizu, S.; Ichimura, K.; et al. The MKK3 MAPK cascade integrates temperature and after-ripening signals to modulate seed germination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2404887121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, S. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in plant signaling. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2022, 64, 301–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gou, X. Receptor-like protein kinases function upstream of MAPKs in regulating plant development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, K.; Shinozaki, K.; Tena, G.; Sheen, J.; Henry, Y.; Champion, A.; Kreis, M.; Zhang, S.; Hirt, H.; Wilson, C.; et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades in plants: A new nomenclature. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, A.; Nepal, M.P.; Piya, S.; Subramanian, S.; Rohila, J.S.; Reese, R.N.; Benson, B.V. Identification, nomenclature, and evolutionary relationships of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) genes in soybean. Evol. Bioinform. 2013, 9, 363–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.; Zheng, X.; Sun, B.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, J.; Lyu, S.; Yu, H.; Chen, P.; Chen, W.; Fan, Z.; et al. MKK3 cascade regulates seed dormancy through a negative feedback loop modulating ABA signal in rice. Rice 2024, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Ding, L.; Zhang, S.; Shan, S.; Xiong, X.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, L.; Luo, Y.; et al. The MKK3–MPK7 cascade phosphorylates ERF4 and promotes its rapid degradation to release seed dormancy in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1743–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, N.S.; Dockter, C.; Berkowitz, O.; Collins, H.M.; Hooi, M.; Lu, Q.; Burton, R.A.; Bulone, V.; Skadhauge, B.; Whelan, J.; et al. Transcriptional and biochemical analyses of gibberellin expression and content in germinated barley grain. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 1870–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.A.; Kai, X.I. Expression and functional analyses of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MPK) cascade genes in response to phytohormones in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Yuan, M. Update on the roles of rice MAPK cascades. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, M.; Rengasamy, B.; Sinha, A.K. Revisiting the role of MAPK signalling pathway in plants and its manipulation for crop improvement. Plant. Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 277–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakodi, M.; Lu, Q.; Pidon, H.; Rabanus-Wallace, M.T.; Bayer, M.; Lux, T.; Guo, Y.; Jaegle, B.; Badea, A.; Bekele, W.; et al. Structural variation in the pangenome of wild and domesticated barley. Nature 2024, 636, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning-Geist, B.; Gordhandas, S.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhou, Q.; Iasonos, A.; Da Cruz Paula, A.; Mandelker, D.; Long Roche, K.; Zivanovic, O.; Maio, A.; et al. MAPK pathway genetic alterations are associated with prolonged overall survival in low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 4456–4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.F.; Ingram, K.; Huang, E.J.; Parksong, J.; McKenney, C.; Bever, G.S.; Regot, S. Systematic analysis of the MAPK signaling network reveals MAP3K-driven control of cell fate. Cell Syst. 2022, 13, 885–894.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.J.; Parksong, J.; Peterson, A.F.; Torres, F.; Regot, S.; Bever, G.S. Refined phylogenetic ortholog inference reveals coevolutionary expansion of the MAPK signaling network through finetuning of pathway specificity. J. Mol. Evol. 2025, 93, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malamos, P.; Papanikolaou, C.; Gavriatopoulou, M.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Terpos, E.; Souliotis, V.L. The interplay between the DNA damage response (DDR) network and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway in multiple myeloma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez-Osuna, A.; Calatrava, V.; Galvan, A.; Fernandez, E.; Llamas, A. Identification of the MAPK cascade and its relationship with nitrogen metabolism in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westphal, R.S.; Tavalin, S.J.; Lin, J.W.; Alto, N.M.; Fraser, I.D.; Langeberg, L.K.; Sheng, M.; Scott, J.D. Regulation of NMDA receptors by an associated phosphatase-kinase signaling complex. Science 1999, 285, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen, B.; Taylor, S.; Ghosh, G. Regulation of protein kinases; controlling activity through activation segment conformation. Mol. Cell 2004, 15, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekkelman, M.L.; de Vries, I.; Joosten, R.P.; Perrakis, A. AlphaFill: Enriching AlphaFold models with ligands and cofactors. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, C.J.; He, Q.X.; Luo, Z.; Yao, H.; Wang, Z.X.; Wu, J.W. Crystal structure of the phosphorylated Arabidopsis MKK5 reveals activation mechanism of MAPK kinases: Activation mechanism of AtMKK5. ABBS 2022, 54, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanner, R.; Sallam, A.H.; Guo, Y.; Jayakodi, M.; Himmelbach, A.; Fiebig, A.; Simmons, J.; Bethke, G.; Lee, Y.; Pacheco Arge, L.W.; et al. Whole-genome resequencing of the wild barley diversity collection: A resource for identifying and exploiting genetic variation for cultivated barley improvement. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2025, jkaf261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Bielawski, J.P. Statistical methods for detecting molecular adaptation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2000, 15, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zeng, S.; Xu, C.; Qiu, W.; Liang, Y.; Joshi, T.; Xu, D. MusiteDeep: A deep-learning framework for general and kinase-specific phosphorylation site prediction. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3909–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, R.T.; Musil, M.; Stourac, J.; Damborsky, J.; Bednar, D. Fully automated ancestral sequence reconstruction using FireProtASR. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musil, M.; Khan, R.T.; Beier, A.; Stourac, J.; Konegger, H.; Damborsky, J.; Bednar, D. FireProtASR: A web server for fully automated ancestral sequence reconstruction. Brief Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bittrich, S.; Segura, J.; Duarte, J.M.; Burley, S.K.; Rose, Y. RCSB protein Data Bank: Exploring protein 3D similarities via comprehensive structural alignments. Bioinformatics 2024, 40, btae370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriata, A.M.; Gierut, A.M.; Oleniecki, T.; Ciemny, M.P.; Kolinski, A.; Kurcinski, M.; Kmiecik, S. CABS-flex 2.0: A web server for fast simulations of flexibility of protein structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W338–W343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróblewski, K.; Zalewski, M.; Kuriata, A.; Kmiecik, S. CABS-flex 3.0: An online tool for simulating protein structural flexibility and peptide modeling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, W95–W101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithin, C.; Fornari, R.P.; Pilla, S.P.; Wroblewski, K.; Zalewski, M.; Madaj, R.; Kolinski, A.; Macnar, J.M.; Kmiecik, S. Exploring protein functions from structural flexibility using CABS-flex modeling. Protein Sci. 2024, 33, e5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, L.; Feig, M. One bead per residue can describe all-atom protein structures. Structure 2024, 32, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pravda, L.; Sehnal, D.; Toušek, D.; Navrátilová, V.; Bazgier, V.; Berka, K.; Svobodová Vareková, R.; Koca, J.; Otyepka, M. MOLEonline: A web-based tool for analyzing channels, tunnels and pores (2018 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W368–W373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochnev, Y.; Durrant, J.D. FPocketWeb: Protein pocket hunting in a web browser. J. Cheminform. 2022, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurrus, E.; Engel, D.; Star, K.; Monson, K.; Brandi, J.; Felberg, L.E.; Brookes, D.H.; Wilson, L.; Chen, J.; Liles, K.; et al. Improvements to the APBS biomolecular solvation software suite. Prot. Sci. 2018, 27, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.A. Kinetic and catalytic mechanisms of protein kinases. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 2271–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieß, M.; Göddeke, H.; Groenhof, G.; Schäfer, L.V. Molecular mechanism of ATP hydrolysis in an ABC transporter. ACS Ctr. Sci. 2018, 4, 1334–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.; Sakon, J.; Fan, C. Crystal structures of Escherichia coli glucokinase and insights into phosphate binding. Acta Crystallogr. F Struct. Biol. Commun. 2025, 81, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, S.; Wendt, T.; Dockter, C.; Thomsen, H.C.; Rasmussen, M.; Jørgensen, M.E.; Lu, Q.; Voss, C.; Murozuka, E.; Østerberg, J.T.; et al. FIND-IT: Accelerated trait development for a green evolution. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N.; Chunletia, R.S.; Badigannavar, A.M.; Mondal, S. Role of alanine aminotransferase in crop resilience to climate change: A critical review. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2024, 30, 1935–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienert, S.; Waterhouse, A.; de Beer, T.A.; Tauriello, G.; Studer, G.; Bordoli, L.; Schwede, T. The SWISS-MODEL Repository-new features and functionality. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, D313–D319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Tao, H.; He, J.; Huang, S.Y. The HDOCK server for integrated protein–protein docking. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 1829–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.; Jindal, A.; Ghani, U.; Kotelnikov, S.; Egbert, M.; Hashemi, N.; Vajda, S.; Padhorny, D.; Kozakov, D. Elucidation of protein function using computational docking and hotspot analysis by ClusPro and FTMap. Acta Crystallogr. 2022, D78, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, E.; Darden, T.; Nabuurs, S.B.; Finkelstein, A.; Vriend, G. Making optimal use of empirical energy functions: Force-field parameterization in crystal space. Proteins 2004, 57, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, E.; Joo, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, J.; Raman, S.; Thompson, J.; Tyka, M.; Baker, D.; Karplus, K. Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: Four approaches that performed well in CASP8. Proteins 2009, 77, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R.A.; MacArthur, M.W.; Moss, D.S.; Thornton, J.M. PROCHECK—A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 1993, 26, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, G.N.; Ramakrishnan, C.; Sasisekharan, V. Stereochemistry of polypeptide chain configurations. J. Mol. Biol. 1963, 7, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A. Figtree v1.4.3; Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, 2018. Available online: https://beast.community/figtree (accessed on 23 November 2025).

- Henderson, S.W.; Nourmohammadi, S.; Hrmova, M. Protein structural modelling and transport thermodynamics reveal that plant cation–chloride cotransporters mediate potassium–chloride symport. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luang, S.; Fernández-Luengo, X.; Streltsov, V.A.; Maréchal, J.-D.; Masgrau, L.; Hrmova, M. The structure and dynamics of water networks underlie catalytic efficiency in a plant glycoside exo-hydrolase. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, N.; Sicheritz-Pontén, T.; Gupta, R.; Gammeltoft, S.; Brunak, S. Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics 2004, 4, 1633–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Tucker, M.R.; Burton, R.A.; Shirley, N.J.; Little, A.; Morris, J.; Milne, L.; Houston, K.; Hedley, P.E.; Waugh, R.; et al. The dynamics of transcript abundance during cellularisation of developing barley endosperm. Plant Phys. 2016, 170, 1549–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høie, M.H.; Kiehl, E.N.; Petersen, B.; Nielsen, M.; Winther, O.; Nielsen, H.; Hallgren, J.; Marcatili, P. NetSurfP-3.0: Accurate and fast prediction of protein structural features by protein language models and deep learning. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W510–W515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Genetic Variants | MKK3 Activity | Dormancy | Risk of PHS |

|---|---|---|---|

| E165 Q165 | lower higher | longer shorter | lower higher |

| N260 T260 | higher lower | shorter longer | higher lower |

| A79 V79 | lower higher | longer shorter | lower higher |

| G350 R350 | not known (slightly lower mRNA) not known (slightly higher mRNA) | not known not known | not known not known |

| N383 D383 | higher (slightly higher mRNA) lower (slightly lower mRNA) | not known not known | not known not known |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hrmova, M.; Dockter, C.; Krsticevic, F.; Jørgensen, M.E.; Skadhauge, B.; Fincher, G.B. Dormancy Versus Germination: 3D Protein Modeling and Evolutionary Analyses Define the Roles of Genetic Variants in the Barley MKK3 Enzyme. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010530

Hrmova M, Dockter C, Krsticevic F, Jørgensen ME, Skadhauge B, Fincher GB. Dormancy Versus Germination: 3D Protein Modeling and Evolutionary Analyses Define the Roles of Genetic Variants in the Barley MKK3 Enzyme. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010530

Chicago/Turabian StyleHrmova, Maria, Christoph Dockter, Flavia Krsticevic, Morten Egevang Jørgensen, Birgitte Skadhauge, and Geoffrey B. Fincher. 2026. "Dormancy Versus Germination: 3D Protein Modeling and Evolutionary Analyses Define the Roles of Genetic Variants in the Barley MKK3 Enzyme" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010530

APA StyleHrmova, M., Dockter, C., Krsticevic, F., Jørgensen, M. E., Skadhauge, B., & Fincher, G. B. (2026). Dormancy Versus Germination: 3D Protein Modeling and Evolutionary Analyses Define the Roles of Genetic Variants in the Barley MKK3 Enzyme. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010530