Genetic Evolution of Melanoma: Comparative Analysis of Candidate Gene Mutations in Healthy Skin, Nevi, and Tumors from the Same Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

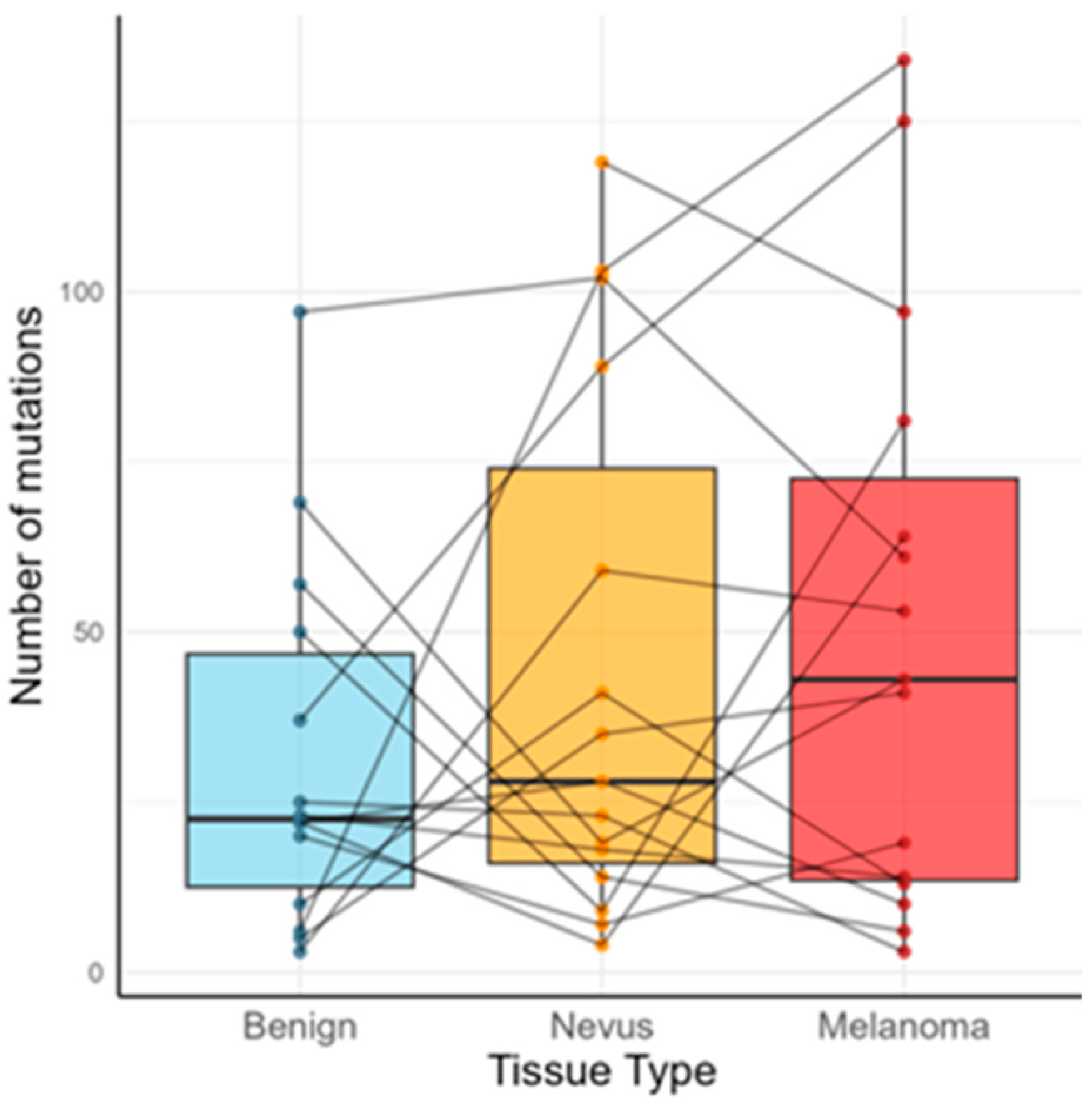

2.1. Mutational Burden and Key Recurrent Genes (Cohort-Level)

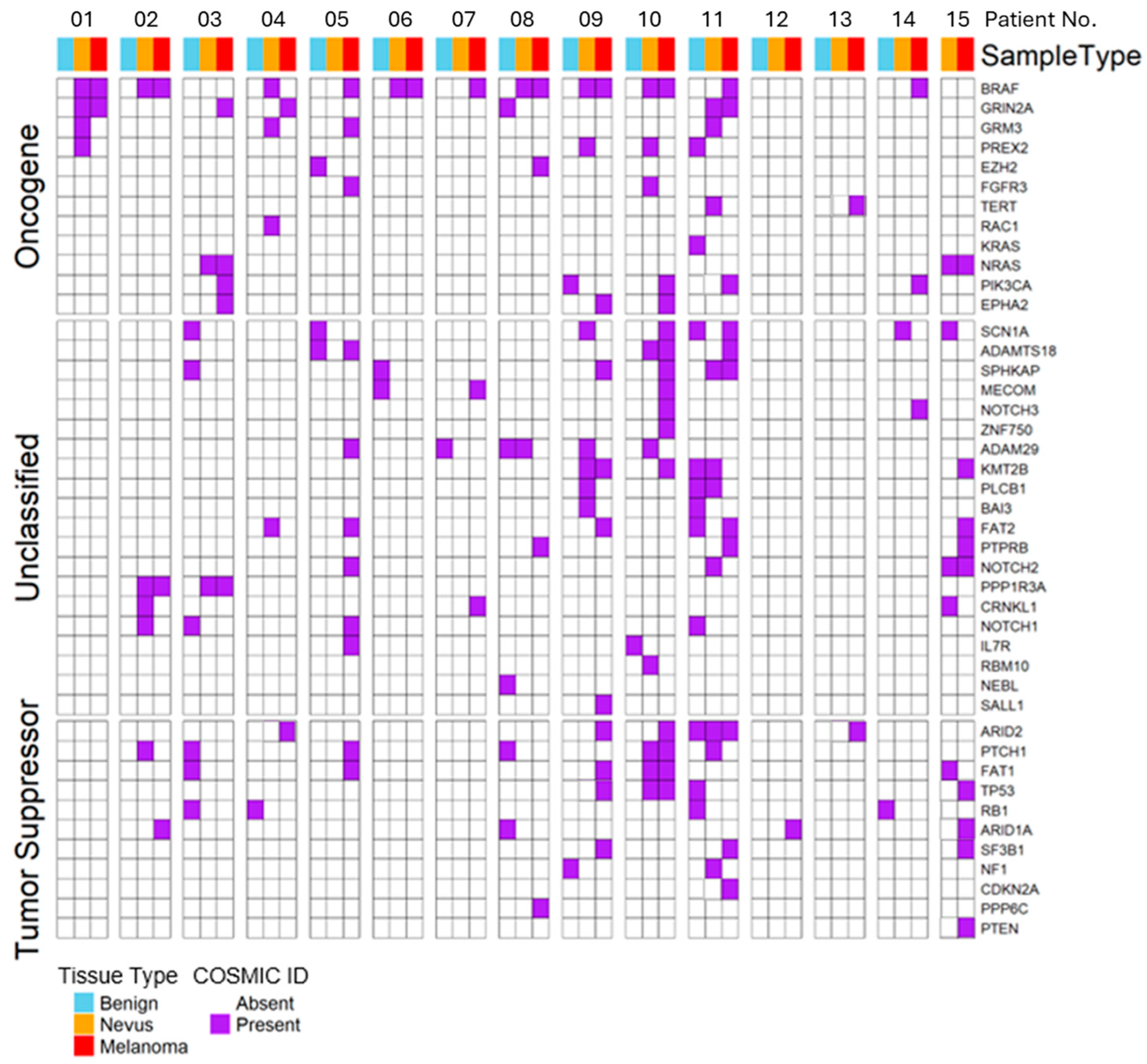

2.2. Mutations in Driver Genes

2.3. Association of VAFs with Different Mutation Types

2.4. UV-Associated Mutations

2.5. Concordance Between Matched Nevus and Melanoma

2.6. Tumor-Private (“Progression”) Events

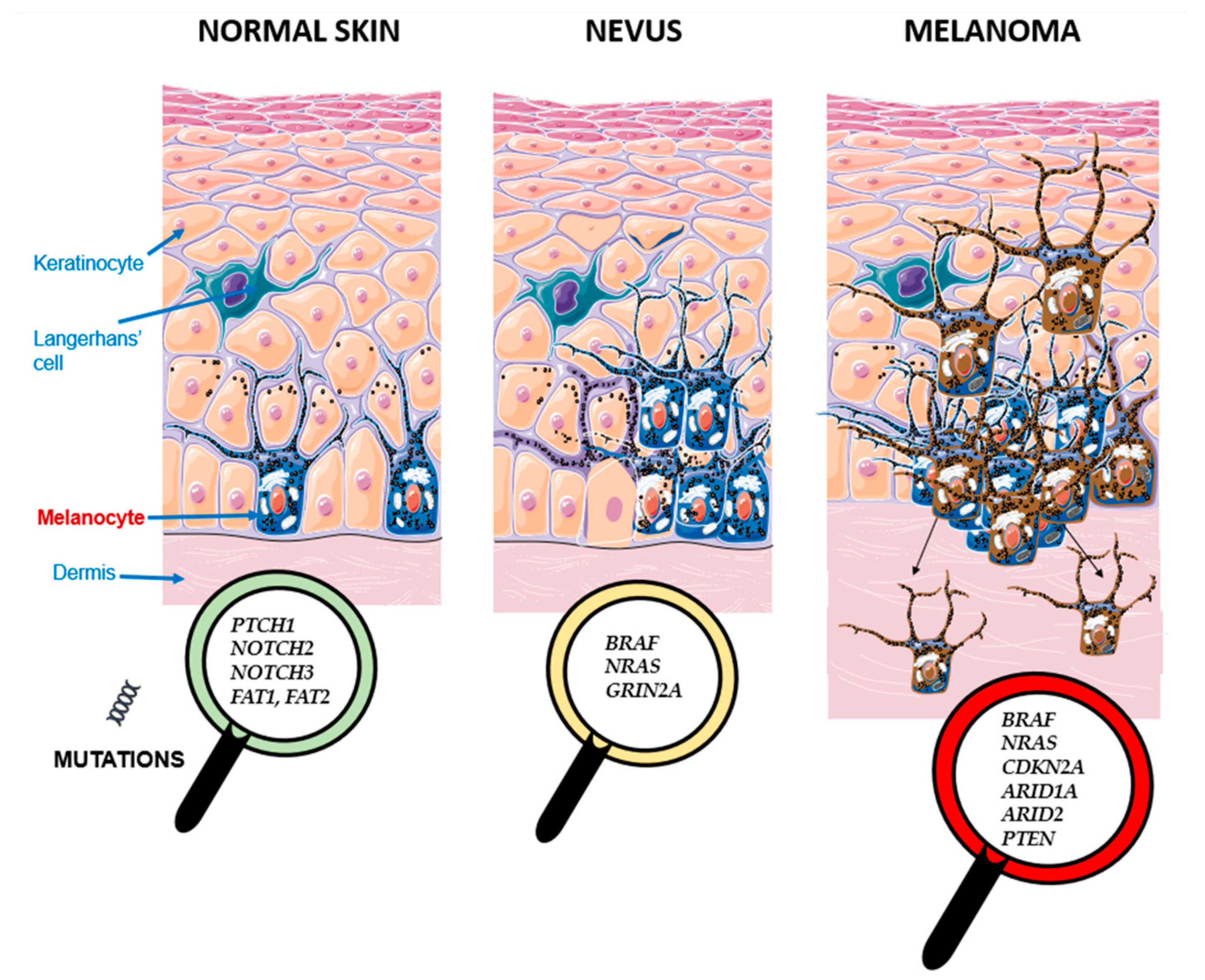

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, D.L.; Saladi, R.N.; Fox, J.L. Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer. Int. J. Dermatol. 2010, 49, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodis, E.; Watson, I.R.; Kryukov, G.V.; Arold, S.T.; Imielinski, M.; Theurillat, J.P.; Nickerson, E.; Auclair, D.; Li, L.; Place, C.; et al. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell 2012, 150, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschandl, P.; Berghoff, A.S.; Preusser, M.; Burgstaller-Muehlbacher, S.; Pehamberger, H.; Okamoto, I.; Kittler, H. NRAS and BRAF mutations in melanoma-associated nevi and uninvolved nevi. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, H.; Bignell, G.R.; Cox, C.; Stephens, P.; Edkins, S.; Clegg, S.; Teague, J.; Woffendin, H.; Garnett, M.J.; Bottomley, W.; et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002, 417, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shitara, D.; Tell-Martí, G.; Badenas, C.; Enokihara, M.M.; Alós, L.; Larque, A.B.; Michalany, N.; Puig-Butille, J.A.; Carrera, C.; Malvehy, J.; et al. Mutational status of naevus-associated melanomas. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 173, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, M.S.; Tan, J.M.; Tom, L.; Jagirdar, K.; Lambie, D.; Schaider, H.; Soyer, H.P.; Sturm, R.A. Whole-Exome Sequencing of Acquired Nevi Identifies Mechanisms for Development and Maintenance of Benign Neoplasms. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1636–1644, Erratum in J. Invest. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 2085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2018.06.174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shain, A.H.; Yeh, I.; Kovalyshyn, I.; Sriharan, A.; Talevich, E.; Gagnon, A.; Dummer, R.; North, J.; Pincus, L.; Ruben, B.; et al. The Genetic Evolution of Melanoma from Precursor Lesions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1926–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martincorena, I.; Roshan, A.; Gerstung, M.; Ellis, P.; Van Loo, P.; McLaren, S.; Wedge, D.C.; Fullam, A.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Tubio, J.M.; et al. High burden and pervasive positive selection of somatic mutations in normal human skin. Science 2015, 348, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernando, B.; Dietzen, M.; Parra, G.; Gil-Barrachina, M.; Pitarch, G.; Mahiques, L.; Valcuende-Cavero, F.; McGranahan, N.; Martinez-Cadenas, C. The effect of age on the acquisition and selection of cancer driver mutations in sun-exposed normal skin. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, J.A.; Fridlyand, J.; Kageshita, T.; Patel, H.N.; Busam, K.J.; Kutzner, H.; Cho, K.H.; Aiba, S.; Bröcker, E.B.; LeBoit, P.E.; et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 2135–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessinioti, C.; Geller, A.C.; Stratigos, A.J. A review of nevus-associated melanoma: What is the evidence? J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 1927–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shreberk-Hassidim, R.; Ostrowski, S.M.; Fisher, D.E. The Complex Interplay between Nevi and Melanoma: Risk Factors and Precursors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobre, E.G.; Nichita, L.; Popp, C.; Zurac, S.; Neagu, M. Assessment of RAS-RAF-MAPK Pathway Mutation Status in Healthy Skin, Benign Nevi, and Cutaneous Melanomas: Pilot Study Using Droplet Digital PCR. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeifer, G.P.; You, Y.H.; Besaratinia, A. Mutations induced by ultraviolet light. Mutat. Res. 2005, 571, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, P.M.; Harper, U.L.; Hansen, K.S.; Yudt, L.M.; Stark, M.; Robbins, C.M.; Moses, T.Y.; Hostetter, G.; Wagner, U.; Kakareka, J.; et al. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat. Genet. 2003, 33, 19–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colebatch, A.J.; Ferguson, P.; Newell, F.; Kazakoff, S.H.; Witkowski, T.; Dobrovic, A.; Johansson, P.A.; Saw, R.P.M.; Stretch, J.R.; McArthur, G.A.; et al. Molecular Genomic Profiling of Melanocytic Nevi. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 1762–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, N.K.; Wilmott, J.S.; Waddell, N.; Johansson, P.A.; Field, M.A.; Nones, K.; Patch, A.M.; Kakavand, H.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Burke, H.; et al. Whole-genome landscapes of major melanoma subtypes. Nature 2017, 545, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shain, A.H.; Bastian, B.C. From melanocytes to melanomas. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, C.; Rito, C.; Beretti, F.; Cesinaro, A.M.; Piñeiro-Maceira, J.; Seidenari, S.; Pellacani, G. De novo melanoma and melanoma arising from pre-existing nevus: In vivo morphologic differences as evaluated by confocal microscopy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 65, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honobe, A.; Sakai, K.; Togashi, Y.; Ohnuma, T.; Kawamura, T.; Nishio, K.; Inozume, T. Heterogeneity in congenital melanocytic nevi contributes to multicentric melanomagenesis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2020, 100, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rank | Gene | No. of Mutations | % of Total Variants | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | BRAF | 21 | 8.2% | Recurrent V600E in multiple patients |

| 2 | NRAS | 16 | 6.3% | Q61K/Q61R hotspot; shared nevus–melanoma lineage |

| 3 | TP53 | 14 | 5.5% | Found mainly in melanoma samples |

| 4 | CDKN2A | 13 | 5.1% | Both p16 and p14^ARF isoforms affected |

| 5 | ARID1A | 11 | 4.3% | Often truncating or frameshift mutations; in melanoma |

| 6 | ARID2 | 10 | 3.9% | Commonly co-mutated with ARID1A in melanoma |

| 7 | PTEN | 9 | 3.5% | Loss-of-function variants enriched in melanoma |

| 8 | NF1 | 8 | 3.1% | Consistent with RAS pathway dysregulation |

| 9 | PREX2 | 7 | 2.7% | Known melanoma driver, higher in tumors |

| 10 | EZH2 | 6 | 2.3% | Missense and splicing variants in nevi and melanoma |

| Tissue Type | Syn/Nonsyn Ratio | Median VAF Syn | Median VAF Nonsyn Non-Drivers | Median VAF Nonsyn Drivers | Proportion UV (Syn) | Proportion UV (Nonsyn) | p (UV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal skin | 0.31 | 0.095 | 0.128 | 0.133 | 0.71 | 0.53 | 0.16 |

| Nevus | 0.25 | 0.121 | 0.152 | 0.159 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.12 |

| Melanoma | 0.24 | 0.118 | 0.161 | 0.179 | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.33 |

| All tissues combined | 0.27 | 0.112 | 0.145 | 0.151 | 0.68 | 0.50 | 0.08 |

| Activating Mutation | VAF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient No. | MAPK-Pathway Mutated Gene | Nevus | Melanoma | Nevus | Melanoma |

| P01 | BRAF | Val600Glu | Val600Glu | 0.076 | 0.157 |

| P02 | BRAF | Val600Glu | Val600Glu | 0.071 | 0.203 |

| P03 | NRAS | Gln61Arg | Gln61Arg | 0.074 | 0.238 |

| P06 | BRAF | Val600Glu | Val600Glu | 0.085 | 0.315 |

| P08 | BRAF | Val600Glu | Val600Glu | 0.137 | 0.204 |

| P09 | BRAF | Val600Glu | Val600Glu | 0.105 | 0.351 |

| P10 | BRAF | Val600Glu | Val600Glu | 0.142 | 0.235 |

| P15 | NRAS | Gln61Lys | Gln61Lys | 0.062 | 0.073 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gil-Barrachina, M.; Hernando, B.; Perez-Pastor, G.; Alegre-de-Miquel, V.; Valenzuela-Oñate, C.; Minguez-Lujan, S.; Monfort-Lanzas, P.; Tomas-Bort, E.; Marques-Torrejon, M.A.; Martinez-Cadenas, C. Genetic Evolution of Melanoma: Comparative Analysis of Candidate Gene Mutations in Healthy Skin, Nevi, and Tumors from the Same Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010532

Gil-Barrachina M, Hernando B, Perez-Pastor G, Alegre-de-Miquel V, Valenzuela-Oñate C, Minguez-Lujan S, Monfort-Lanzas P, Tomas-Bort E, Marques-Torrejon MA, Martinez-Cadenas C. Genetic Evolution of Melanoma: Comparative Analysis of Candidate Gene Mutations in Healthy Skin, Nevi, and Tumors from the Same Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010532

Chicago/Turabian StyleGil-Barrachina, Marta, Barbara Hernando, Gemma Perez-Pastor, Victor Alegre-de-Miquel, Cristian Valenzuela-Oñate, Sandra Minguez-Lujan, Pablo Monfort-Lanzas, Elena Tomas-Bort, Maria Angeles Marques-Torrejon, and Conrado Martinez-Cadenas. 2026. "Genetic Evolution of Melanoma: Comparative Analysis of Candidate Gene Mutations in Healthy Skin, Nevi, and Tumors from the Same Patients" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010532

APA StyleGil-Barrachina, M., Hernando, B., Perez-Pastor, G., Alegre-de-Miquel, V., Valenzuela-Oñate, C., Minguez-Lujan, S., Monfort-Lanzas, P., Tomas-Bort, E., Marques-Torrejon, M. A., & Martinez-Cadenas, C. (2026). Genetic Evolution of Melanoma: Comparative Analysis of Candidate Gene Mutations in Healthy Skin, Nevi, and Tumors from the Same Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010532