Aging at the Crossroads of Cuproptosis and Ferroptosis: From Molecular Pathways to Age-Related Pathologies and Therapeutic Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review Methodology

3. Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis: Molecular Mechanisms

3.1. Key Molecular Pathways

3.2. Crosstalk Between Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis Pathways

4. Aging

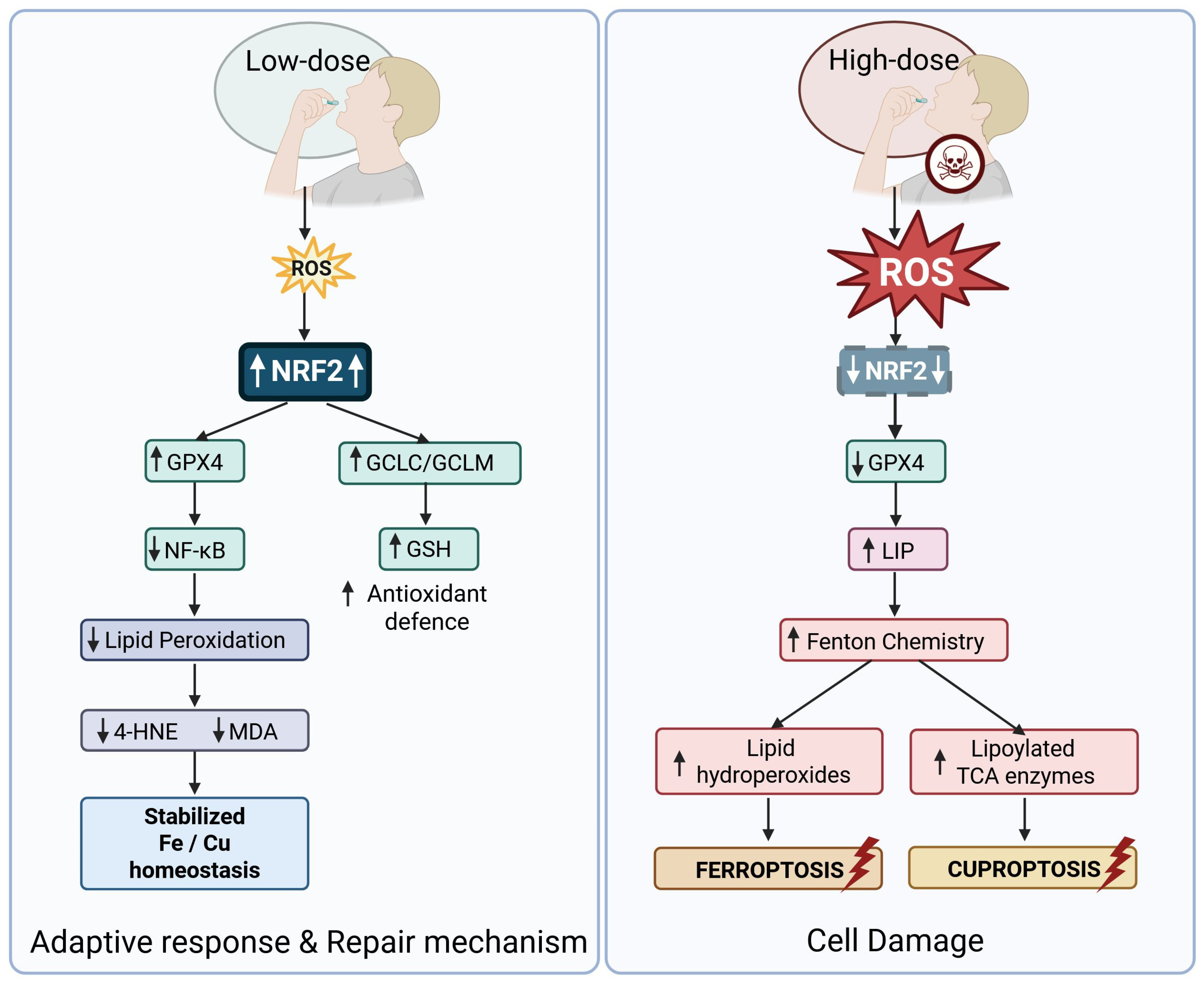

4.1. Mitochondrial and Oxidative Stress in Aging

4.2. Link Between Mitochondrial and Oxidative Stress, and Ferro-/Cuproptosis

4.3. Chronic Inflammation in Aging

4.4. Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis as Missing Links in Inflammaging

5. Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis in Aging: Disease Associations

5.1. Neurodegenerative Diseases

5.2. Cardiovascular Diseases

5.3. Cancer

5.3.1. Aging–Metal Biology and Cancer Vulnerability

5.3.2. Crosstalk Between the Two Pathways and Implications for Cancer in Older Individuals

5.3.3. Translational Outlook and Cautions

5.4. COVID-19 and Other Infections

5.4.1. Aging and Infection-Related Ferroptotic and Cuproptotic Vulnerability

5.4.2. Clinical and Research Implications

5.5. Osteoarticular Diseases

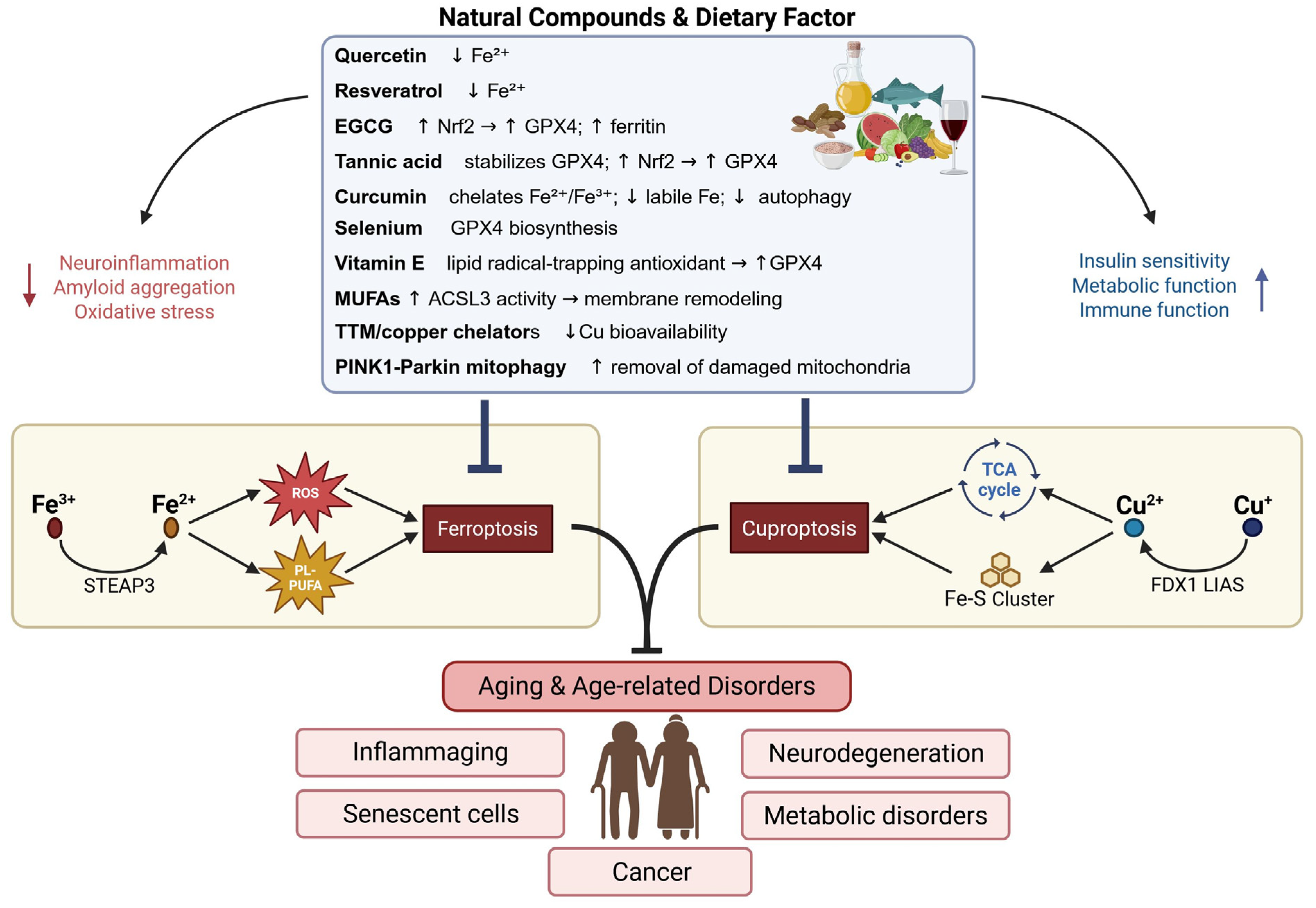

6. Therapeutic Strategies of Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis for Aging and Age-Related Diseases

6.1. Pharmacological Modulation

6.2. Natural Modulation of Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis

- (i)

- Direct radical-scavenging, which neutralizes lipid peroxyl radicals and interrupts lipid peroxidation chains;

- (ii)

- Transition-metal chelation, lowering labile Fe2+ and Cu+ pools that catalyse Fenton-type reactions;

- (iii)

- Activation of adaptive transcriptional programs, particularly the NRF2–ARE axis, which promotes GSH synthesis and GPX4-mediated detoxification of lipid hydroperoxides [88].

6.2.1. Polyphenols: Combined Radical Scavenging, Metal Binding and Nrf2 Induction

6.2.2. Dietary Trace-Metal Modulation and Phytate Effects

6.2.3. Lifestyle Interventions: Exercise, Mitochondrial Quality Control and Nutrient Signalling

6.2.4. Targeted Delivery: Nanomedicine Approaches to Chelation and Redox Modulation

6.2.5. Repleting the GSH–GPX4 Axis: Cysteine Donors and Translational Evidence

6.2.6. Modulating the Aging Microenvironment: Senolytics, Efferocytosis and Inflammasome Inhibition

6.2.7. Integrative, Biomarker-Guided Geroprotective Strategies

7. Limitations of the Study

8. Conclusions

8.1. Emerging Biomarkers

8.2. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| •OH | hydroxyl radicals |

| 4-HNE | 4-hydroxynonenal |

| AA | arachidonic acid |

| ACSL3 | acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3 |

| ACSL4 | acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4 |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AdA | adrenic acid |

| AIFM2 | apoptosis-inducing factor, mitochondrion-associated, 2 |

| ALOX5 | arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase |

| ALS | amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AOPP | advanced oxidation protein products |

| ARE | antioxidant response element |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| ATP7B | ATPase copper transporting beta |

| BAK | BCL-2-antagonist killer |

| BAX | BCL-2-associated X |

| BBC3 | BCL2-binding component 3 |

| BCL2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BCS | bathocuproine disulfonate |

| BID | BH3-interacting domain death agonist |

| BSO | buthionine sulfoximine |

| cGAS–STING | cyclic GMP–AMP synthase–stimulator of interferon genes |

| CLP | cecal ligation and puncture |

| CNV | copy number variation |

| CoQ | Coenzyme Q10 |

| COVID-19 | coronavirus disease 2019 |

| CP | ceruloplasmin |

| CRG | copper death-related genes |

| CRGs | cuproptosis-related genes |

| CTR1 | copper transporter 1 |

| CVD | cardiovascular diseases |

| DAMPs | damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DEP | deferiprone |

| DFO | deferoxamine |

| DFX | deferasirox |

| DHODH | dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (quinone) |

| DLAT | dihydrolipoyl acetyltransferase |

| DMT1 | divalent metal transporter 1 |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| EGCG | epigallocatechin-3-gallate |

| ETC | electron transport chain |

| FDX1 | ferredoxin 1 |

| FEACR | ferroptosis-associated circRNA |

| Fer-1 | ferrostatin-1 |

| Fe-S | iron-sulfur |

| FINs | ferroptosis inducers |

| FOXO1 | forkhead box O1 |

| FPN1 | ferroportin |

| FRAP | ferric reducing antioxidant power |

| FSP1 | Ferroptosis Suppressor Protein 1 |

| FTH1 | ferritin heavy chain 1 |

| GCSH | glycine cleavage system H-protein |

| GPX4 | glutathione peroxidase 4 |

| GSH | glutathione |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| HD | Huntington’s disease |

| HFpEF | heart failure with preserved ejection fraction |

| HIF-1α | hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha |

| HMGB1 | high mobility group box 1 |

| HT22 | HT-22 mouse hippocampal neuronal cell line |

| I/R | ischemia–reperfusion |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1 beta |

| JAK-STAT | Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription |

| Keap1 | kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| KGD | α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase |

| LAD | left anterior descending |

| LC–MS | liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| LIAS | lipoic acid synthetase |

| LIP | labile iron pool |

| LIPT1 | lipoyltransferase 1 |

| L-NAME | N(G)-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester |

| L-OH | lipid alcohols |

| L-OOH | lipid hydroperoxides |

| LOXs | lipoxygenases |

| LPCAT3 | acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4)–activated, lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 |

| LPI | labile plasma iron |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| MCC950 | N-[[(1, 7-hexahydro-s-indacen-4-yl)amino]carbonyl]-4-(1-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)-2-furansulfonamide sodium salt |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| mHTT | mutant huntingtin |

| MI | myocardial infarction |

| MnSOD | manganese superoxide dismutase |

| MT | metallothionein |

| mtDNA | mitochondrial DNA |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| MUFAs | monounsaturated fatty acids |

| NAC | N-acetylcysteine |

| NAD | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NAMPT | nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase |

| NCOA4 | nuclear receptor coactivator 4 |

| NFS1 | cysteine desulfurase |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NLRP3 | NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 |

| NRF2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| NTBI | non-transferrin-bound iron |

| O2•− | superoxide anion |

| OA | osteoarthritis |

| OXPHOS | oxidative phosphorylation |

| p16INK4a (CDKN2A) | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A |

| p21CIP1/WAF1 (CDKN1A) | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A |

| p62 | sequestosome 1 |

| PAMPs | pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PDC | pyruvate dehydrogenase complex |

| PGC-1α | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1-alpha |

| PINK1 | PTEN-induced kinase 1 |

| PPARγ | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PRRs | pattern recognition receptors |

| Prx6 | mitochondrial peroxiredoxin 6 |

| PUFAs | polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| PUMA | p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis |

| RA | Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| RAGE | receptor for advanced glycation end-products |

| RAS | rat sarcoma virus |

| RB | retinoblastoma |

| RCD | regulated cell death |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RSL3 | (1S,3R)-methyl 2-(2-chloroacetyl)-1-(4-(methoxycarbonyl)phenyl)-2,3,4,9-tetrahydro-1H-pyrido[4-b]indole-3-carboxylate |

| RTAs | radical-trapping antioxidants |

| RVG29 | rabies virus glycoprotein 29 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| SASP | senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| SCD1 | stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 |

| SEC24B | protein transport protein Sec24 homolog B, COPII coat complex component |

| SIRT1 | sirtuin 1 |

| SLC31A1 | solute carrier family 31 (copper transporter), member 1 |

| SLC7A11 | solute carrier family 7 member 11 |

| SNpc | substantia nigra pars compacta |

| TAX1BP1 | Tax1-binding protein 1 |

| TBARS | thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| TCA | tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| TfR1 | transferrin receptor-1 |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| TNF-α | tumour necrosis factor-α |

| TPP | thiamin pyrophosphate |

| TTM | tetrathiomolybdate ammonium |

| UCP2 | uncoupling protein-2 |

| WD | Wilson’s disease |

References

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023, 186, 243–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinex, F.M. Biochemistry of Aging. Science 1961, 134, 1402–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, C.; Bonafè, M.; Valensin, S. Human immunosenescence: The prevailing of innate immunity, the failing of clonotypic immunity, and the filling of immunological space. Vaccine 2000, 18, 1717–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, L.; Fabbri, E. Inflammageing: Chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K.; Kauppinen, A. Inflammaging: Disturbed interplay between autophagy and inflammasomes. Aging 2012, 4, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostinis, P.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; Amelio, I.; Andrews, D.W.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 486–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.; Zhang, X.; Yang, M.; Dong, X. Recent Progress in Ferroptosis Inducers for Cancer Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1904197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetkov, P.; Coy, S.; Petrova, B.; Dreishpoon, M.; Verma, A.; Abdusamad, M.; Rossen, J.; Joesch-Cohen, L.; Humeidi, R.; Spangler, R.D.; et al. Copper induces cell death by targeting lipoylated TCA cycle proteins. Science 2022, 375, 1254–1261, Erratum in Science 2022, 376, eabq4855. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abq4855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobine, P.A.; Brady, D.C. Cuproptosis: Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying copper-induced cell death. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 1786–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, V.; Scapagnini, G.; Giuffrida Stella, A.M.; Bates, T.E.; Clark, J.B. Mitochondrial involvement in brain function and dysfunction: Relevance to aging, neurodegenerative disorders and longevity. Neurochem. Res. 2001, 26, 739–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, L.M.; Libedinsky, A.; Elorza, A.A. Role of Copper on Mitochondrial Function and Metabolism. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 711227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulcke, F.; Dringen, R.; Scheiber, I.F. Neurotoxicity of Copper. Adv. Neurobiol. 2017, 18, 313–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, B.R.; Jiang, X.; Gu, W. Emerging Mechanisms and Disease Relevance of Ferroptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2020, 30, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, M.; Avila, D.S.; da Rocha, J.B.; Aschner, M. Metals, oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: A focus on iron, manganese and mercury. Neurochem. Int. 2013, 62, 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolma, S.; Lessnick, S.L.; Hahn, W.C.; Stockwell, B.R. Identification of genotype-selective antitumor agents using synthetic lethal chemical screening in engineered human tumor cells. Cancer Cell 2003, 3, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Monian, P.; Pan, Q.; Zhang, W.; Xiang, J.; Jiang, X. Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell Res. 2016, 26, 1021–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, M.S.; Ruiz, J.; Watts, J.L. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Drive Lipid Peroxidation during Ferroptosis. Cells 2023, 12, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.S.; Kim, K.J.; Gaschler, M.M.; Patel, M.; Shchepinov, M.S.; Stockwell, B.R. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E4966-4975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursini, F.; Maiorino, M.; Valente, M.; Ferri, L.; Gregolin, C. Purification from pig liver of a protein which protects liposomes and biomembranes from peroxidative degradation and exhibits glutathione peroxidase activity on phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxides. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta 1982, 710, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, B.R.; Friedmann Angeli, J.P.; Bayir, H.; Bush, A.I.; Conrad, M.; Dixon, S.J.; Fulda, S.; Gascón, S.; Hatzios, S.K.; Kagan, V.E.; et al. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell 2017, 171, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agmon, E.; Solon, J.; Bassereau, P.; Stockwell, B.R. Modeling the effects of lipid peroxidation during ferroptosis on membrane properties. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong-Ekkabut, J.; Xu, Z.; Triampo, W.; Tang, I.M.; Tieleman, D.P.; Monticelli, L. Effect of lipid peroxidation on the properties of lipid bilayers: A molecular dynamics study. Biophys. J. 2007, 93, 4225–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heuvingh, J.; Bonneau, S. Asymmetric oxidation of giant vesicles triggers curvature-associated shape transition and permeabilization. Biophys. J. 2009, 97, 2904–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfipour Nasudivar, S.; Pedrera, L.; García-Sáez, A.J. Iron-Induced Lipid Oxidation Alters Membrane Mechanics Favoring Permeabilization. Langmuir 2024, 40, 25061–25068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilka, O.; Shah, R.; Li, B.; Friedmann Angeli, J.P.; Griesser, M.; Conrad, M.; Pratt, D.A. On the Mechanism of Cytoprotection by Ferrostatin-1 and Liproxstatin-1 and the Role of Lipid Peroxidation in Ferroptotic Cell Death. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassannia, B.; Van Coillie, S.; Vanden Berghe, T. Ferroptosis: Biological Rust of Lipid Membranes. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 35, 487–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonnoy, P.; Karttunen, M.; Wong-Ekkabut, J. Alpha-tocopherol inhibits pore formation in oxidized bilayers. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 5699–5704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.F.; Zou, T.; Tuo, Q.Z.; Xu, S.; Li, H.; Belaidi, A.A.; Lei, P. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms and links with diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Cao, N.; Zeng, S.; Zhu, W.; Fu, X.; Liu, W.; Fan, S. Role of mitochondria in the regulation of ferroptosis and disease. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1301822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Chen, X.; Kang, R.; Kroemer, G. Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkholi, R.; Floros, K.V.; Chipuk, J.E. The Role of BH3-Only Proteins in Tumor Cell Development, Signaling, and Treatment. Genes Cancer 2011, 2, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, C.; Humayun, D.; Skouta, R. Cuproptosis: Unraveling the Mechanisms of Copper-Induced Cell Death and Its Im-plication in Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2024, 16, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Yan, D.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Kang, R.; Klionsky, D.J.; Kroemer, G.; Chen, X.; Tang, D.; Liu, J. Copper-dependent autophagic degradation of GPX4 drives ferroptosis. Autophagy 2023, 19, 1982–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wu, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, M.; Yue, Z.; Wu, Z.; Liu, L.; Li, F. Copper Depletion Strongly Enhances Ferroptosis via Mitochondrial Perturbation and Reduction in Antioxidative Mechanisms. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Kang, R.; Klionsky, D.J.; Tang, D.; Liu, J.; Chen, X. Copper metabolism in cell death and autophagy. Autophagy 2023, 19, 2175–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liang, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, C. Ferroptosis and cuproptposis in kidney Diseases: Dysfunction of cell metabolism. Apoptosis 2024, 29, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Huang, R.; Yuan, Y. Crosstalk Between Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration: Mechanisms, Therapeutic Targets, and Future Directions. JOR Spine 2025, 8, e70080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Guan, M.; Zhang, X.; Yu, J.; Han, M.; Li, Z. Copper metabolism in osteoarthritis and its relation to oxidative stress and ferroptosis in chondrocytes. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1472492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenchov, R.; Sasso, J.M.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Q.A. Aging Hallmarks and Progression and Age-Related Diseases: A Landscape View of Research Advancement. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, M.; Lee, S.; Schmitt, C.A. Cellular senescence: Neither irreversible nor reversible. J. Exp. Med. 2024, 221, e20232136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, M.; Din, A.U.; Ali, H.; Yang, G.; Ren, W.; Wang, L.; Fan, X.; Yang, S. Implication of ferroptosis in aging. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Wang, K.; Zhao, X.; Song, B.; Yao, T.; Liu, T.; Gao, G.; Lu, W.; Liu, C. Emerging insights into cuproptosis and copper metabolism: Implications for age-related diseases and potential therapeutic strategies. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1335122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, D.; Yao, L.; Sun, Y.; Li, D.; Le, J.; Dian, Y.; Zeng, F.; Chen, X.; Deng, G. The molecular mechanism and therapeutic landscape of copper and cuproptosis in cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickert, A.; Schwantes, A.; Fuhrmann, D.C.; Brüne, B. Inflammation in a ferroptotic environment. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1474285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royce, G.H.; Brown-Borg, H.M.; Deepa, S.S. The potential role of necroptosis in inflammaging and aging. GeroScience 2019, 41, 795–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, C.; Bonafè, M.; Valensin, S.; Olivieri, F.; De Luca, M.; Ottaviani, E.; De Benedictis, G. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 908, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadenas, E.; Davies, K. Mitochondrial free radical generation, oxidative stress, and aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 29, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, K.R.; Bigelow, M.L.; Kahl, J.; Singh, R.; Coenen-Schimke, J.; Raghavakaimal, S.; Nair, K.S. Decline in skeletal muscle mitochondrial function with aging in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 5618–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujoth, G.C.; Hiona, A.; Pugh, T.D.; Someya, S.; Panzer, K.; Wohlgemuth, S.E.; Hofer, T.; Seo, A.Y.; Sullivan, R.; Jobling, W.A.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science 2005, 309, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifunovic, A.; Wredenberg, A.; Falkenberg, M.; Spelbrink, J.N.; Rovio, A.T.; Bruder, C.E.; Bohlooly, Y.M.; Gidlöf, S.; Oldfors, A.; Wibom, R.; et al. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature 2004, 429, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokolenko, I.; Venediktova, N.; Bochkareva, A.; Wilson, G.L.; Alexeyev, M.F. Oxidative stress induces degradation of mitochondrial DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, 2539–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.B.; Chinnery, P.F. The dynamics of mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy: Implications for human health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2015, 16, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009, 417, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, S.E.; Guo, H.; Fedarko, N.; DeZern, A.; Fried, L.P.; Xue, Q.L.; Leng, S.; Beamer, B.; Walston, J.D. Glutathione peroxidase enzyme activity in aging. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2008, 63, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevalo, J.A.; Xing, D.; Leija, R.G.; Thorwald, M.A.; Moreno-Santillán, D.D.; Allen, K.N.; Selleghin-Veiga, G.; Avalos, H.C.; Utke, E.; Conner, J.L.; et al. Age-related declines in mitochondrial Prdx6 contribute to dysregulated muscle bioenergetics. Redox Biol. 2025, 86, 103808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płóciniczak, A.; Bukowska-Olech, E.; Wysocka, E. The Complexity of Oxidative Stress in Human Age-Related Diseases—A Review. Metabolites 2025, 15, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Tang, D.; Liu, X. Mitochondria as multifaceted regulators of ferroptosis. Life Metab. 2022, 1, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.H.; Fefelova, N.; Pamarthi, S.H.; Gwathmey, J.K. Molecular Mechanisms of Ferroptosis and Relevance to Cardiovascular Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egozi, S.; Ast, T. Rust and redemption: Iron–sulfur clusters and oxygen in human disease and health. Metallomics 2025, 17, mfaf022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Tang, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Bao, H.; Tang, C.; Dong, X.; Li, X.; Yang, Q.; Yan, Y.; et al. The mechanism of ferroptosis and its related diseases. Mol. Biomed. 2023, 4, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, D.; Leija, R.; Arevalo, J.; Brooks, G.; Vázquez-Medina, J. Mitochondrial Peroxiredoxin 6 Declines with Aging in Parallel with Increases in Hydrogen Peroxide Generation. Physiology 2024, 39, S1, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canizal-Garcia, M.; Olmos-Orizaba, B.E.; Moreno-Jiménez, M.; Calderón-Cortés, E.; Saavedra-Molina, A.; Cortés-Rojo, C. Glutathione peroxidase 2 (Gpx2) preserves mitochondrial function and decreases ROS levels in chronologically aged yeast. Free Radic. Res. 2021, 55, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Morris, H.; Cronin, M.T. Metals, toxicity and oxidative stress. Curr. Med. Chem. 2005, 12, 1161–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.P.; Chen, Y.; Wei, X.; Yu, B.; Xiong, Z.G.; Lu, C.; Hu, W. Novel insights into ferroptosis: Implications for age-related diseases. Theranostics 2020, 10, 11976–11997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lu, K.; Jiang, X.; Wei, Q.; Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Jin, H.; Feng, L. Ferroptosis inducers enhanced cuproptosis induced by copper ionophores in primary liver cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 42, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromadzka, G.; Tarnacka, B.; Flaga, A.; Adamczyk, A. Copper Dyshomeostasis in Neurodegenerative Diseases—Therapeutic Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Jia, Y.; Dıng, Y.-X.; Bai, J.; Cao, F.; Li, F. The crosstalk between ferroptosis and mitochondrial dynamic regulatory networks. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 2756–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppé, J.P.; Patil, C.K.; Rodier, F.; Sun, Y.; Muñoz, D.P.; Goldstein, J.; Nelson, P.S.; Desprez, P.Y.; Campisi, J. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, 2853–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Jat, P. Mechanisms of Cellular Senescence: Cell Cycle Arrest and Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 645593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.J.; Wijshake, T.; Tchkonia, T.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Childs, B.G.; van de Sluis, B.; Kirkland, J.L.; van Deursen, J.M. Clearance of p16Ink4a-positive senescent cells delays ageing-associated disorders. Nature 2011, 479, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Souroullas, G.P.; Diekman, B.O.; Krishnamurthy, J.; Hall, B.M.; Sorrentino, J.A.; Parker, J.S.; Sessions, G.A.; Gudkov, A.V.; Sharpless, N.E. Cells exhibiting strong p16(INK4a) promoter activation in vivo display features of senescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2603–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Farr, J.N.; Weigand, B.M.; Palmer, A.K.; Weivoda, M.M.; Inman, C.L.; Ogrodnik, M.B.; Hachfeld, C.M.; Fraser, D.G.; et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaffidi, P.; Misteli, T.; Bianchi, M.E. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature 2002, 418, 191–195, Erratum in Nature 2010, 467, 622. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature00858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seong, S.-Y.; Matzinger, P. Hydrophobicity: An ancient damage-associated molecular pattern that initiates innate immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baechle, J.J.; Chen, N.; Makhijani, P.; Winer, S.; Furman, D.; Winer, D.A. Chronic inflammation and the hallmarks of aging. Mol. Metab. 2023, 74, 101755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, J.F.; Ramírez, C.M.; Mittelbrunn, M. Inflammaging, a targetable pathway for preventing cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc. Res. 2024, 121, 1537–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinon, F.; Burns, K.; Tschopp, J. The inflammasome: A molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol. Cell 2002, 10, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, H.; Kouadir, M.; Song, H.; Shi, F. Recent advances in the mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its inhibitors. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Yang, T.; Xiao, J.; Xu, C.; Alippe, Y.; Sun, K.; Kanneganti, T.D.; Monahan, J.B.; Abu-Amer, Y.; Lieberman, J.; et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation triggers gasdermin D-independent inflammation. Sci. Immunol. 2021, 6, eabj3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouge, M.; Larsson, N. The role of mitochondrial DNA mutations and free radicals in disease and ageing. J. Intern. Med. 2013, 273, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Yazdi, A.S.; Menu, P.; Tschopp, J. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 2011, 469, 221–225, Erratum in Nature 2011, 475, 122. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vénéreau, E.; Ceriotti, C.; Bianchi, M.E. DAMPs from Cell Death to New Life. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, K.W.; Choi, J.S.; Yu, B.P. Molecular inflammation hypothesis of aging based on the anti-aging mechanism of calorie restriction. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2002, 59, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youm, Y.H.; Grant, R.W.; McCabe, L.R.; Albarado, D.C.; Nguyen, K.Y.; Ravussin, A.; Pistell, P.; Newman, S.; Carter, R.; Laque, A.; et al. Canonical Nlrp3 inflammasome links systemic low-grade inflammation to functional decline in aging. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritsenko, A.; Green, J.P.; Brough, D.; Lopez-Castejon, G. Mechanisms of NLRP3 priming in inflammaging and age related diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020, 55, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Thadathil, N.; Selvarani, R.; Nicklas, E.H.; Wang, D.; Miller, B.F.; Richardson, A.; Deepa, S.S. Necroptosis contributes to chronic inflammation and fibrosis in aging liver. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidu, S.; Amponsah, S.K.; Aning, A.; Adams, L.; Kumi, J.; Ampem-Danso, E.; Hamidu, F.; Mumin Mohammed, M.A.; Ador, G.T.; Khatun, S. Modulating Ferroptosis in Aging: The Therapeutic Potential of Natural Products. J. Aging Res. 2025, 2025, 8832992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Zou, J.; Zhong, X.; Liu, J.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. DAMP signaling networks: From receptors to diverse pathophysiological functions. J. Adv. Res. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eissa, N.; Al-Houqani, M.; Sadeq, A.; Ojha, S.K.; Sasse, A.; Sadek, B. Current Enlightenment About Etiology and Pharmacological Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, F.; Liu, J.; Tang, D.; Kang, R. Oxidative Damage and Antioxidant Defense in Ferroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 586578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliani, K.T.K.; Grivei, A.; Nag, P.; Wang, X.; Rist, M.; Kildey, K.; Law, B.; Ng, M.S.; Wilkinson, R.; Ungerer, J.; et al. Hypoxic human proximal tubular epithelial cells undergo ferroptosis and elicit an NLRP3 inflammasome response in CD1c+ dendritic cells. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Hao, C.; Huangfu, J.; Srinivasagan, R.; Zhang, X.; Fan, X. Aging Lens Epithelium is Susceptible to Ferroptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 167, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Wulfmeyer, V.; Chen, R.; Erlangga, Z.; Sinning, J.; Mässenhausen, A.; Sörensen-Zender, I.; Beer, K.; Vietinghoff, S.; Haller, H.; et al. Induction of ferroptosis selectively eliminates senescent tubular cells. Am. J. Transplant. 2022, 22, 2158–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, A.P.; Shadel, G.S.; Ghosh, S. Mitochondria in innate immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.J.; Zhou, X.Y.; Qin, D.L.; Qiao, Q.; Wang, Q.Z.; Li, S.Y.; Zhu, Y.F.; Li, Y.P.; Zhou, J.M.; Cai, H.; et al. Inhibition of Ferroptosis Delays Aging and Extends Healthspan Across Multiple Species. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2416559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Yao, Y.M.; Tian, Y.P. Ferroptosis: A Trigger of Proinflammatory State Progression to Immunogenicity in Necroinflammatory Disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 701163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. HMGB1 is a mediator of cuproptosis-related sterile inflammation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 996307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhivaki, D.; Kagan, J.C. Innate immune detection of lipid oxidation as a threat assessment strategy. Nat. reviews. Immunol. 2022, 22, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berndt, C.; Alborzinia, H.; Amen, V.S.; Ayton, S.; Barayeu, U.; Bartelt, A.; Bayir, H.; Bebber, C.M.; Birsoy, K.; Böttcher, J.P.; et al. Ferroptosis in health and disease. Redox Biol. 2024, 75, 103211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Pan, J.; Bao, Q. Ferroptosis in senescence and age-related diseases: Pathogenic mechanisms and potential intervention targets. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Kang, R.; Tang, D.; Liu, J. Ferroptosis: Principles and significance in health and disease. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 17, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Z.; Lin, Q. Ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases: Potential mechanisms of exercise intervention. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1622544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lv, L.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, H.; Jiang, B.; Han, Y.; Pan, X.; Zhou, X.; et al. From copper homeostasis to cuproptosis: A new perspective on CNS immune regulation and neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1581045, Erratum in Front Neurol. 2025, 16, 1664184. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2025.1664184. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, L.; Sun, J.; Xia, L.; Shi, Q.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, M.; Fan, C.; Sun, B. Ferroptosis mechanism and Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 19, 1741–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Yang, K.; Guo, H.; Zeng, J.; Wang, S.; Xu, H.; Ge, A.; Zeng, L.; Chen, S.; Ge, J. Mechanisms of ferroptosis in Alzheimer’s disease and therapeutic effects of natural plant products: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 164, 114312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.; Jeandriens, J.; Parkes, H.; So, P. Iron dyshomeostasis, lipid peroxidation and perturbed expression of cys-tine/glutamate antiporter in Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence of ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2020, 32, 101494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onukwufor, J.O.; Dirksen, R.T.; Wojtovich, A.P. Iron Dysregulation in Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Alzheimer’s Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaldan, S.; Clatworthy, S.A.S.; Gamell, C.; Meggyesy, P.M.; Rigopoulos, A.-T.; Haupt, S.; Haupt, Y.; Denoyer, D.; Adlard, P.A.; Bush, A.I.; et al. Iron accumulation in senescent cells is coupled with impaired ferritinophagy and inhibition of ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagerer, S.M.; Vionnet, L.; van Bergen, J.M.G.; Meyer, R.; Gietl, A.F.; Pruessmann, K.P.; Hock, C.; Unschuld, P.G. Hippocampal iron patterns in aging and mild cognitive impairment. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1598859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.W.; Cha, H.W.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.H.; Yang, H.; Yoon, S.; Boonpraman, N.; Yi, S.S.; Yoo, I.D.; Moon, J.S. NOX4 promotes ferroptosis of astrocytes by oxidative stress-induced lipid peroxidation via the impairment of mitochondrial metabolism in Alzheimer’s diseases. Redox Biol. 2021, 41, 101947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, D.A. Brain lipid peroxidation and alzheimer disease: Synergy between the Butterfield and Mattson laboratories. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 64, 101049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorwald, M.A.; Godoy-Lugo, J.A.; Garcia, G.; Silva, J.; Kim, M.; Christensen, A.; Mack, W.J.; Head, E.; O’Day, P.A.; Benayoun, B.A.; et al. Iron-associated lipid peroxidation in Alzheimer’s disease is increased in lipid rafts with decreased ferroptosis sup-pressors, tested by chelation in mice. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 21, e14541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, P.K.; Goel, A.; Bush, A.I.; Punjabi, K.; Joon, S.; Mishra, R.; Tripathi, M.; Garg, A.; Kumar, N.K.; Sharma, P.; et al. Hippocampal glutathione depletion with enhanced iron level in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease compared with healthy elderly participants. Brain Commun. 2022, 4, fcac215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Dar, N.J.; Na, R.; McLane, K.D.; Yoo, K.; Han, X.; Ran, Q. Enhanced defense against ferroptosis ameliorates cognitive impairment and reduces neurodegeneration in 5xFAD mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 180, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cui, K.; Zhu, X.; Wang, S.; Yang, Q.; Fang, G. 8-weeks aerobic exercise ameliorates cognitive deficit and mitigates ferroptosis triggered by iron overload in the prefrontal cortex of APP (Swe)/PSEN (1dE9) mice through Xc(-)/GPx4 pathway. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1453582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, G.; Hussain, M.S.; Khan, Y.; Fatima, R.; Ahmad, S.; Sultana, A.; Alam, P. Ferroptosis and its contribution to cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Brain Res. 2025, 1864, 149776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Luo, X.; Yin, Y.; Thomas, E.R.; Liu, K.; Wang, W.; Li, X. The interplay of iron, oxidative stress, and α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease progression. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, D.J.; Lei, P.; Ayton, S.; Roberts, B.R.; Grimm, R.; George, J.L.; Bishop, D.P.; Beavis, A.D.; Donovan, S.J.; McColl, G.; et al. An iron-dopamine index predicts risk of parkinsonian neurodegeneration in the substantia nigra pars compacta. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 2160–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Jin, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Fei, G.; Ye, F.; Pan, X.; Wang, C.; Zhong, C. Iron Deposition Leads to Neuronal α-Synuclein Pathology by Inducing Autophagy Dysfunction. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Gholam Azad, M.; Dharmasivam, M.; Richardson, V.; Quinn, R.J.; Feng, Y.; Pountney, D.L.; Tonissen, K.F.; Mellick, G.D.; Yanatori, I.; et al. Parkinson’s disease: Alterations in iron and redox biology as a key to unlock therapeutic strategies. Redox Biol. 2021, 41, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, I.; Reimann, K.; Jankuhn, S.; Kirilina, E.; Stieler, J.; Sonntag, M.; Meijer, J.; Weiskopf, N.; Reinert, T.; Arendt, T.; et al. Cell specific quantitative iron mapping on brain slices by immuno-µPIXE in healthy elderly and Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2021, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen van Rensburg, Z.; Abrahams, S.; Bardien, S.; Kenyon, C. Toxic Feedback Loop Involving Iron, Reactive Oxygen Species, α-Synuclein and Neuromelanin in Parkinson’s Disease and Intervention with Turmeric. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 5920–5936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, M.S.; Schumacher-Schuh, A.; Cardoso, A.M.; Bochi, G.V.; Baldissarelli, J.; Kegler, A.; Santana, D.; Chaves, C.M.; Schetinger, M.R.; Moresco, R.N.; et al. Iron and Oxidative Stress in Parkinson’s Disease: An Observational Study of Injury Biomarkers. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scolari Grotto, F.; Glaser, V. Are high copper levels related to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases? A systematic review and meta-analysis of articles published between 2011 and 2022. Biometals Int. J. Role Met. Ions Biol. Biochem. Med. 2024, 37, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yin, Y.L.; Liu, X.Z.; Shen, P.; Zheng, Y.G.; Lan, X.R.; Lu, C.B.; Wang, J.Z. Current understanding of metal ions in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Ayton, S.; Agrawal, S.; Dhana, K.; Bennett, D.A.; Barnes, L.L.; Leurgans, S.E.; Bush, A.I.; Schneider, J.A. Brain copper may protect from cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease pathology: A community-based study. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 4307–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisaglia, M.; Bubacco, L. Copper Ions and Parkinson’s Disease: Why Is Homeostasis So Relevant? Biomolecules 2020, 10, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doroszkiewicz, J.; Farhan, J.A.; Mroczko, J.; Winkel, I.; Perkowski, M.; Mroczko, B. Common and Trace Metals in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Gao, X.; Xu, H.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gou, X. The Emerging Roles of Ferroptosis in Huntington’s Disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2019, 21, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xia, X.; Basnet, D.; Zheng, J.C.; Huang, J.; Liu, J. Mechanisms of Ferroptosis and Emerging Links to the Pathology of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 904152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.; Handley, R.R.; Lehnert, K.; Snell, R.G. From Pathogenesis to Therapeutics: A Review of 150 Years of Huntington’s Disease Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaiya, S.; Cortes-Gutierrez, M.; Herb, B.R.; Coffey, S.R.; Legg, S.R.W.; Cantle, J.P.; Colantuoni, C.; Carroll, J.B.; Ament, S.A. Single-Nucleus RNA-Seq Reveals Dysregulation of Striatal Cell Identity Due to Huntington’s Disease Mutations. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 5534–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallaksen-Greene, S.J.; Janiszewska, A.; Benton, K.; Hou, G.; Dick, R.; Brewer, G.J.; Albin, R.L. Evaluation of tetrathiomolybdate in the R6/2 model of Huntington disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2009, 452, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skouta, R.; Dixon, S.J.; Wang, J.; Dunn, D.E.; Orman, M.; Shimada, K.; Rosenberg, P.A.; Lo, D.C.; Weinberg, J.M.; Linkermann, A.; et al. Ferrostatins inhibit oxidative lipid damage and cell death in diverse disease models. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4551–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Su, Z.; Kon, N.; Chu, B.; Li, H.; Jiang, X.; Luo, J.; Stockwell, B.R.; Gu, W. ALOX5-mediated ferroptosis acts as a distinct cell death pathway upon oxidative stress in Huntington’s disease. Genes Dev. 2023, 37, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobato, A.G.; Ortiz-Vega, N.; Zhu, Y.; Neupane, D.; Meier, K.K.; Zhai, R.G. Copper enhances aggregational toxicity of mutant huntingtin in a Drosophila model of Huntington’s Disease. Biochim. Et Biophys. acta. Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 166928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, J.H.; Kama, J.A.; Lieberman, G.; Chopra, R.; Dorsey, K.; Chopra, V.; Volitakis, I.; Cherny, R.A.; Bush, A.I.; Hersch, S. Mechanisms of copper ion mediated Huntington’s disease progression. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, N.; Wang, J.; Jiang, H.; Xie, J. Astroglial and microglial contributions to iron metabolism disturbance in Parkinson’s disease. Biochim. Et Biophys. acta. Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, H.H.; Johnsen, K.B.; Moos, T. Iron deposits in the chronically inflamed central nervous system and contributes to neurodegeneration. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 1607–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddell, J.R.; Hilton, J.B.W.; Kysenius, K.; Billings, J.L.; Nikseresht, S.; McInnes, L.E.; Hare, D.J.; Paul, B.; Mercer, S.W.; Belaidi, A.A.; et al. Microglial ferroptotic stress causes non-cell autonomous neuronal death. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Zhang, J. Iron Metabolism, Ferroptosis, and the Links with Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Gao, X.; Zhou, S. New Target for Prevention and Treatment of Neuroinflammation: Microglia Iron Accumulation and Ferroptosis. ASN Neuro 2022, 14, 17590914221133236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, S.K.; Zelic, M.; Han, Y.; Teeple, E.; Chen, L.; Sadeghi, M.; Shankara, S.; Guo, L.; Li, C.; Pontarelli, F.; et al. Microglia ferroptosis is regulated by SEC24B and contributes to neurodegeneration. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kciuk, M.; Gielecińska, A.; Kałuzińska-Kołat, Ż.; Yahya, E.B.; Kontek, R. Ferroptosis and cuproptosis: Metal-dependent cell death pathways activated in response to classical chemotherapy—Significance for cancer treatment? Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Wang, H.; Han, D.; Xie, E.; Yang, X.; Wei, J.; Gu, S.; Gao, F.; Zhu, N.; Yin, X.; et al. Ferroptosis as a target for protection against cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryabov, V.V.; Maslov, L.N.; Vyshlov, E.V.; Mukhomedzyanov, A.V.; Kilin, M.; Gusakova, S.V.; Gombozhapova, A.E.; Pan-teleev, O.O. Ferroptosis, a Regulated Form of Cell Death, as a Target for the Development of Novel Drugs Preventing Ische-mia/Reperfusion of Cardiac Injury, Cardiomyopathy and Stress-Induced Cardiac Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.T.; Zhang, G.Y.; Hua, Y.; Fan, H.J.; Han, X.; Xu, H.L.; Chen, G.H.; Liu, B.; Xie, L.P.; Zhou, Y.C. Ferrostatin-1 suppresses cardiomyocyte ferroptosis after myocardial infarction by activating Nrf2 signaling. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2023, 75, 1467–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, K.; Liu, Y.; Huang, J.; Yao, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhou, L. Uncoupling Protein 2 Alleviates Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury by Inhibiting Cardiomyocyte Ferroptosis. J. Vasc. Res. 2024, 61, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Li, X.M.; Zhao, X.M.; Li, F.H.; Wang, S.C.; Wang, K.; Li, R.F.; Zhou, L.Y.; Liang, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Circular RNA FEACR inhibits ferroptosis and alleviates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by interacting with NAMPT. J. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 30, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, M.; Zhu, S.; Du, Z.; Lin, L.; Ma, J.; Reiter, R.J.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Li, G.; Zou, R.; et al. Metallothionein rescues doxorubicin cardiomyopathy via mitigation of cuproptosis. Life Sci. 2025, 363, 123379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Cai, S.; Fu, H.; Gan, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Ma, W.; Chen, J.; et al. Copper homeostasis and cuproptosis in myocardial infarction: Molecular mechanisms, treatment strategies and potential therapeutic targets. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1525585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.Z.; Chen, Z.C.; Wang, S.S.; Liu, W.B.; Zhao, C.L.; Zhuang, X.D. NLRP3 inflammasome activation contributes to the pathogenesis of cardiocytes aging. Aging 2021, 13, 20534–20551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiang, L.; Hao, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, T. Inhibition of ferroptosis reverses heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in mice. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, B. Decoding the diet-inflammation nexus: Ferroptosis as a therapeutic target. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, J.; Rhee, J.; Chaudhari, V.; Rosenzweig, A. The Role of Exercise in Cardiac Aging: From Physiology to Molecular Mechanisms. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Jia, D. Exercise Alleviates Cardiovascular Diseases by Improving Mitochondrial Homeostasis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e036555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, M.; Ying, X.; Yuan, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Tian, S.; Yan, X. Caloric restriction increases the resistance of aged heart to myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via modulating AMPK-SIRT(1)-PGC(1a) energy metabolism pathway. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viloria, M.A.D.; Li, Q.; Lu, W.; Nhu, N.T.; Liu, Y.; Cui, Z.Y.; Cheng, Y.J.; Lee, S.D. Effect of exercise training on cardiac mitochondrial respiration, biogenesis, dynamics, and mitophagy in ischemic heart disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 949744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, M.; Rajasekaran, N.S. Exercise, Nrf2 and Antioxidant Signaling in Cardiac Aging. Front. Physiol. 2016, 7, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioscia-Ryan, R.A.; Battson, M.L.; Cuevas, L.M.; Zigler, M.C.; Sindler, A.L.; Seals, D.R. Voluntary aerobic exercise increases arterial resilience and mitochondrial health with aging in mice. Aging 2016, 8, 2897–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Min, J.; Wang, F. Copper homeostasis and cuproptosis in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Huo, C.; Wang, M.; Huang, H.; Zheng, X.; Xie, M. Research progress on cuproptosis in cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1290592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, Z.; Shang, Y.; Zhao, H. Cuproptosis: Molecular mechanisms, cancer prognosis, and therapeutic applications. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Meng, Y.; Li, D.; Yao, L.; Le, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, F.; Chen, X.; Deng, G. Ferroptosis in cancer: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Abdul Razak, S.R.; Han, T.; Ahmad, N.H.; Li, X. Ferroptosis as a potential target for cancer therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarin, M.; Babaie, M.; Eshghi, H.; Matin, M.M.; Saljooghi, A.S. Elesclomol, a copper-transporting therapeutic agent targeting mitochondria: From discovery to its novel applications. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Yu, T.; Sun, J.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, Z.; Ma, M.; Zheng, Z.; He, Y.; Kang, W. Comprehensive analysis of cuproptosis-related immune biomarker signature to enhance prognostic accuracy in gastric cancer. Aging 2023, 15, 2772–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Yuan, S.; Wang, H. Identification of a cuproptosis-related prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target in ovarian cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2025, 29, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, T.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Yang, H.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Li, X. Cuproptosis-related immune checkpoint gene signature: Prediction of prognosis and immune response for hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1000997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, L.; Liao, Q.; Huang, P.; Sun, R.; Yang, X.; Du, J. A five-cuproptosis-related LncRNA Signature: Predicting prognosis, assessing immune function & drug sensitivity in lung squamous cell carcinoma. J. Cancer 2023, 14, 1499–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Lv, H.; Li, G.; Li, H. Single-cell and Multi-omics Analysis Confirmed the Signature and Potential Targets of Cuproptosis in Colorectal Cancer. J. Cancer 2025, 16, 1264–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooko, E.; Ali, N.T.; Efferth, T. Identification of Cuproptosis-Associated Prognostic Gene Expression Signatures from 20 Tumor Types. Biology 2024, 13, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xu, P.; Zhang, F.; Sun, T.; Jiang, H.; Lu, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, P. The cuproptosis-related gene signature serves as a potential prognostic predictor for ovarian cancer using bioinformatics analysis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Hu, Q.; Chen, H.; He, M.; Ma, H.; Zhou, L.; Xu, K.; Ren, H.; Qi, J. Cuproptosis-related signature predicts prognosis, immunotherapy efficacy, and chemotherapy sensitivity in lung adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1127768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, Z. Pan-cancer analysis reveals copper transporters as promising potential targets. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J.Q.; Zhang, S.Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, M.X.; Zheng, Y.Q.; Xie, X.; Zhang, R.; Wang, S.S. Immunomodulation of cuproptosis and ferroptosis in liver cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, W.; Yang, P.; Li, L.; Chen, D.; Wang, C. A ceRNA network-mediated over-expression of cuproptosis-related gene SLC31A1 correlates with poor prognosis and positive immune infiltration in breast cancer. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1194046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, A.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, Z. An association between ATP7B expression and human cancer prognosis and immunotherapy: A pan-cancer perspective. BMC Med. Genom. 2023, 16, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Shapiro, J.S.; Chang, H.C.; Miller, R.A.; Ardehali, H. Aging is associated with increased brain iron through cor-tex-derived hepcidin expression. eLife 2022, 11, e73456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slusarczyk, P.; Mandal, P.K.; Zurawska, G.; Niklewicz, M.; Chouhan, K.; Mahadeva, R.; Jończy, A.; Macias, M.; Szybinska, A.; Cybulska-Lubak, M.; et al. Impaired iron recycling from erythrocytes is an early hallmark of aging. eLife 2023, 12, e79196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, P.; Song, Y.; Ying, G.S.; He, X.; Beard, J.; Dunaief, J.L. Age-dependent and gender-specific changes in mouse tissue iron by strain. Exp. Gerontol. 2009, 44, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeidan, R.S.; Han, S.M.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Xiao, R. Iron homeostasis and organismal aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 72, 101510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, S.; Ripamonti, M.; Moro, A.S.; Cozzi, A. Iron imbalance in neurodegeneration. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musci, G.; Bonaccorsi di Patti, M.C.; Fagiolo, U.; Calabrese, L. Age-related changes in human ceruloplasmin. Evidence for oxidative modifications. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 13388–13395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.; Jiang, W.; Zheng, W. Age-dependent increase of brain copper levels and expressions of copper regulatory proteins in the subventricular zone and choroid plexus. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2015, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Q.; Luo, Z.; Ren, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, G. Iron and copper: Critical executioners of ferroptosis, cuproptosis and other forms of cell death. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wei, H.; Lyu, M.; Yu, Z.; Chen, J.; Lyu, X.; Zhuang, F. Iron retardation in lysosomes protects senescent cells from ferroptosis. Aging 2024, 16, 7683–7703, Erratum in Aging 2024, 16, 11475–11476. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.206052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Li, Q.; Sun, H.; Wang, H. Pharmacological Inhibition of Ferroptosis as a Therapeutic Target for Neurodegenerative Diseases and Strokes. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2300325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Chan, K.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Lin, K.N.; Wang, C.C.; Lau, T.S. Interplay of Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis in Cancer: Dissecting Metal-Driven Mechanisms for Therapeutic Potentials. Cancers 2024, 16, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElhaney, J.E.; Verschoor, C.P.; Andrew, M.K.; Haynes, L.; Kuchel, G.A.; Pawelec, G. The immune response to influenza in older humans: Beyond immune senescence. Immun. Ageing I A 2020, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keilich, S.R.; Bartley, J.M.; Haynes, L. Diminished immune responses with aging predispose older adults to common and uncommon influenza complications. Cell. Immunol. 2019, 345, 103992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyani, P.; Christodoulou, R.; Vassiliou, E. Immunosenescence: Aging and Immune System Decline. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Liu, Y.; Jing, X.; Wang, Y.; Miao, M.; Tao, L.; Zhou, Z.; Xie, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lei, J.; et al. Mortality risk of COVID-19 in elderly males with comorbidities: A multi-country study. Aging 2020, 13, 27–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Liu, Y.; Lu, K.T.; Wei, C.; Su, K.; Hsu, W.T.; Chen, S.C. Comparison of influenza hospitalization outcomes among adults, older adults, and octogenarians: A US national population-based study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, B.; Alu, A.; Hong, W.; Lei, H.; He, X.; Shi, H.; Cheng, P.; Yang, X. Immunosenescence: Signaling pathways, diseases and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinatizadeh, M.R.; Zarandi, P.K.; Ghiasi, M.; Kooshki, H.; Mohammadi, M.; Amani, J.; Rezaei, N. Immunosenescence and inflamm-ageing in COVID-19. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 84, 101818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Fang, L.; Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Jiang, J.; Gao, L. Ferroptotic stress promotes macrophages against intracellular bacteria. Theranostics 2022, 12, 2266–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letafati, A.; Taghiabadi, Z.; Ardekani, O.S.; Abbasi, S.; Najafabadi, A.Q.; Jazi, N.N.; Soheili, R.; Rodrigo, R.; Yavarian, J.; Saso, L. Unveiling the intersection: Ferroptosis in influenza virus infection. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nai, A.; Lorè, N.I.; Pagani, A.; De Lorenzo, R.; Di Modica, S.; Saliu, F.; Cirillo, D.M.; Rovere-Querini, P.; Manfredi, A.A.; Silvestri, L. Hepcidin levels predict Covid-19 severity and mortality in a cohort of hospitalized Italian patients. Am. J. Hematol. 2021, 96, E32–E35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Chen, Y.; Ji, Y.; He, X.; Xue, D. Increased Serum Levels of Hepcidin and Ferritin Are Associated with Severity of COVID-19. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e926178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Zandkarimi, F.; Saqi, A.; Castagna, C.; Tan, H.; Sekulic, M.; Miorin, L.; Hibshoosh, H.; Toyokuni, S.; Uchida, K.; et al. Fatal COVID-19 pulmonary disease involves ferroptosis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltobgy, M.; Johns, F.; Farkas, D.; Leuenberger, L.; Cohen, S.P.; Ho, K.; Karow, S.; Swoope, G.; Pannu, S.; Horowitz, J.C.; et al. Longitudinal transcriptomic analysis reveals persistent enrichment of iron homeostasis and erythrocyte function pathways in severe COVID-19 ARDS. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1397629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melms, J.C.; Biermann, J.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Nair, A.; Tagore, S.; Katsyv, I.; Rendeiro, A.F.; Amin, A.D.; Schapiro, D.; et al. A molecular single-cell lung atlas of lethal COVID-19. Nature 2021, 595, 114–119, Erratum in Nature 2021, 598, E2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03921-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Feng, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, G.; Xu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L. Ferrostatin-1 alleviates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via inhibiting ferroptosis. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2020, 25, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Geng, Z.; Bai, H.; Liu, T.; Zhang, B. Ammonium Ferric Citrate induced Ferroptosis in Non-Small-Cell Lung Carcinoma through the inhibition of GPX4-GSS/GSR-GGT axis activity. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 1899–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankauskas, S.S.; Kansakar, U.; Sardu, C.; Varzideh, F.; Avvisato, R.; Wang, X.; Matarese, A.; Marfella, R.; Ziosi, M.; Gam-bardella, J.; et al. COVID-19 Causes Ferroptosis and Oxidative Stress in Human Endothelial Cells. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurian, S.J.; Mathews, S.P.; Paul, A.; Viswam, S.K.; Kaniyoor Nagri, S.; Miraj, S.S.; Karanth, S. Association of serum ferritin with severity and clinical outcome in COVID-19 patients: An observational study in a tertiary healthcare facility. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2023, 21, 101295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleman, C.; Van Coillie, S.; Ligthart, S.; Choi, S.M.; De Waele, J.; Depuydt, P.; Benoit, D.; Schaubroeck, H.; Francque, S.M.; Dams, K.; et al. Ferroptosis and pyroptosis signatures in critical COVID-19 patients. Cell Death Differ. 2023, 30, 2066–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Wang, S.; Han, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cao, J.; Dong, S.; Li, D.; Lei, M.; Gao, Y.; Liu, C. Role of Ferroptosis in the Progression of COVID-19 and the Development of Long COVID. Curr. Med. Chem. 2025, 32, 4324–4342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackler, J.; Heller, R.A.; Sun, Q.; Schwarzer, M.; Diegmann, J.; Bachmann, M.; Moghaddam, A.; Schomburg, L. Relation of Serum Copper Status to Survival in COVID-19. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govind, V.; Bharadwaj, S.; Sai Ganesh, M.R.; Vishnu, J.; Shankar, K.V.; Shankar, B.; Rajesh, R. Antiviral properties of copper and its alloys to inactivate COVID-19 virus: A review. Biometals 2021, 34, 1217–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, S.S. Copper and immunity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 67, 1064s–1068s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukasewycz, O.A.; Prohaska, J.R. The immune response in copper deficiency. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 1990, 587, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prohaska, J.R.; Lukasewycz, O.A. Effects of copper deficiency on the immune system. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1990, 262, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Xu, M.; Xie, J.; Liu, T.; Xu, X.; Gao, W.; Li, Z.; Bai, X.; Liu, X. Inhibition of Ferroptosis Attenuates Glutamate Excitotoxicity and Nuclear Autophagy in a CLP Septic Mouse Model. Shock 2022, 57, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, H. Autophagy-dependent ferroptosis in infectious disease. J. Transl. Intern. Med. 2023, 11, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haschka, D.; Tymoszuk, P.; Petzer, V.; Hilbe, R.; Heeke, S.; Dichtl, S.; Skvortsov, S.; Demetz, E.; Berger, S.; Seifert, M.; et al. Ferritin H deficiency deteriorates cellular iron handling and worsens Salmonella typhimurium infection by triggering hyperin-flammation. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e141760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Du, Y.; Du, Y.; Bao, D.; Lu, H.; Zhou, X.; Li, R.; Pei, H.; She, H.; et al. Cuproptosis-Related Genes as Prognostic Biomarkers for Sepsis: Insights into Immune Function and Personalized Immunotherapy. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 4229–4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coradduzza, D.; Congiargiu, A.; Chen, Z.; Zinellu, A.; Carru, C.; Medici, S. Ferroptosis and Senescence: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terman, A.; Kurz, T.; Navratil, M.; Arriaga, E.A.; Brunk, U.T. Mitochondrial turnover and aging of long-lived postmitotic cells: The mitochondrial-lysosomal axis theory of aging. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 12, 503–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemart, C.; Seurinck, R.; Stroobants, T.; Van Coillie, S.; De Loor, J.; Choi, S.M.; Roelandt, R.; Rajapurkar, M.; Ligthart, S.; Jorens, P.G.; et al. Potential of biomarker-based enrichment strategies to identify critically ill patients for emerging cell death interventions. Cell Death Differ. 2025, 32, 2284–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadban, C.; García-Unzueta, M.; Agüero, J.; Martín-Audera, P.; Lavín, B.A.; Guerra, A.R.; Berja, A.; Aranda, N.; Guzun, A.; Insua, A.I.; et al. Associations between serum levels of ferroptosis-related molecules and outcomes in stable COPD: An exploratory prospective observational study. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2025, 20, 1761–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Elzen, W.P.; de Craen, A.J.; Wiegerinck, E.T.; Westendorp, R.G.; Swinkels, D.W.; Gussekloo, J. Plasma hepcidin levels and anemia in old age. The Leiden 85-Plus Study. Haematologica 2013, 98, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, L.; Semba, R.D.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ershler, W.B.; Bandinelli, S.; Patel, K.V.; Sun, K.; Woodman, R.C.; Andrews, N.C.; Cotter, R.J.; et al. Proinflammatory state, hepcidin, and anemia in older persons. Blood 2010, 115, 3810–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, M.C.; Meydani, S.N. Iron biology, immunology, aging, and obesity: Four fields connected by the small peptide hormone hepcidin. Adv. Nutr. (Bethesda Md.) 2013, 4, 602–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCranor, B.J.; Langdon, J.M.; Prince, O.D.; Femnou, L.K.; Berger, A.E.; Cheadle, C.; Civin, C.I.; Kim, A.; Rivera, S.; Ganz, T.; et al. Investigation of the role of interleukin-6 and hepcidin antimicrobial peptide in the development of anemia with age. Haematologica 2013, 98, 1633–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röhrig, G.; Rappl, G.; Vahldick, B.; Kaul, I.; Schulz, R.J. Serum hepcidin levels in geriatric patients with iron deficiency anemia or anemia of chronic diseases. Z. Fur Gerontol. Und Geriatr. 2014, 47, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Tuttle, M.S.; Powelson, J.; Vaughn, M.B.; Donovan, A.; Ward, D.M.; Ganz, T.; Kaplan, J. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science 2004, 306, 2090–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaschella, C.; Nai, A.; Silvestri, L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Haematologica 2020, 105, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Feng, Y.H.; Li, Y.X.; He, P.Y.; Zhou, Q.Y.; Tian, Y.P.; Yao, R.Q.; Yao, Y.M. Ferritinophagy: A novel insight into the double-edged sword in ferritinophagy-ferroptosis axis and human diseases. Cell Prolif. 2024, 57, e13621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arosio, P. New Advances in Iron Metabolism, Ferritin and Hepcidin Research. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Han, H. Ferroptosisand Its Role in the Treatment of Sepsis-Related Organ Injury: Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Approaches. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 5715–5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Wu, C.; Odden, M.C.; Kim, D.H. Multimorbidity Patterns, Frailty, and Survival in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2019, 74, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xue, F.; Liu, K.; Zhu, B.; Gao, J.; Yin, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, G. Contribution of ferroptosis and GPX4’s dual functions to osteoarthritis progression. EBioMedicine 2022, 76, 103847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, B.; Xi, C.; Qin, Y.; Lin, X.; Wang, B.; Kong, P.; Yan, J. Ferroptosis Plays a Role in Human Chondrocyte of Osteoarthritis Induced by IL-1β In Vitro. Cartilage 2023, 14, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Dai, T.; Xue, X.; Xia, D.; Feng, Z.; Huang, J.; Chen, X.; Sun, S.; Zhou, J.; et al. Characteristics and time points to inhibit ferroptosis in human osteoarthritis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Fang, Y.; Lin, L.; Long, W.; Wang, L.; Yu, L.; Deng, H.; Wang, D. Upregulating miR-181b promotes ferroptosis in osteoarthritic chondrocytes by inhibiting SLC7A11. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Luo, C.; Li, A.; Cai, F.; Wang, Y.; Pan, X.; Xu, L.; Wang, Z.; Xing, Z.; Yu, L.; et al. Icariin inhibits chondrocyte ferroptosis and alleviates osteoarthritis by enhancing the SLC7A11/GPX4 signaling. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 133, 112010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Dai, T.; Chen, J.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Huang, J.; Xu, W.; Li, S.; Meng, Q. PPARγ activation suppresses chondrocyte ferroptosis through mitophagy in osteoarthritis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zang, G.; Huang, W. SCD1 deficiency exacerbates osteoarthritis by inducing ferroptosis in chondrocytes. Ann. Transl. Med. 2023, 11, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Luo, Z.; Chen, Z.; Lu, Y.; Duan, J.; Yang, Z.; Lu, G. Paeoniflorin mitigates iron overload-induced osteoarthritis by suppressing chondrocyte ferroptosis via the p53/SLC7A11/GPX4 pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 162, 115111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, J.; Si, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, S.; Shen, B. The Role Played by Ferroptosis in Osteoarthritis: Evidence Based on Iron Dyshomeostasis and Lipid Peroxidation. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, F. Cuproptosis: A new form of programmed cell death. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 867–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, H.; Cheng, F.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, A.; Li, M.; Zhang, M.; Lou, P.; Zhu, Y.; Tong, P.; Zhang, Y. Cuproptosis in osteoarthritis: Exploring chondrocyte cuproptosis and therapeutic avenues. J. Orthop. Transl. 2025, 55, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Li, J.; Shi, M.; Li, Y.; Sun, N.; Xi, K.; Li, X.; Zhao, D.; Leng, X.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Hypoxia, cuproptosis, and osteoarthritis: Unraveling the molecular crosstalk. Redox Biol. 2025, 85, 103757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipsky, P.E. Immunosuppression by D-penicillamine in vitro. Inhibition of human T lymphocyte proliferation by copper- or ceruloplasmin-dependent generation of hydrogen peroxide and protection by monocytes. J. Clin. Investig. 1984, 73, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Jiang, T.; Wang, J.; Ge, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, C.; Wang, W. Cuprorivaite microspheres inhibit cuproptosis and oxidative stress in osteoarthritis via Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Mater. today. Bio 2024, 29, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, C.; Wang, G. The Roles of Exosomes upon Metallic Ions Stimulation in Bone Regeneration. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorwald, M.A.; Godoy-Lugo, J.A.; Christensen, A.; Pike, C.J.; Forman, H.J.; Finch, C.E. Deferoxamine treatment decreases amyloid fibrils and lowers iron mediated oxidative damage in ApoEFAD mice. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2025, 20, e095418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Luo, J.; Wang, C.; Kapilevich, L.; Zhang, X.A. Roles and mechanisms of copper homeostasis and cuproptosis in osteoarticular diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Q.; Xu, L. How do different lipid peroxidation mechanisms contribute to ferroptosis? Cell reports. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miotto, G.; Rossetto, M.; Di Paolo, M.L.; Orian, L.; Venerando, R.; Roveri, A.; Vučković, A.M.; Bosello Travain, V.; Zaccarin, M.; Zennaro, L.; et al. Insight into the mechanism of ferroptosis inhibition by ferrostatin-1. Redox Biol. 2020, 28, 101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthonymuthu, T.S.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Sun, W.Y.; Mikulska-Ruminska, K.; Shrivastava, I.H.; Tyurin, V.A.; Cinemre, F.B.; Dar, H.H.; VanDemark, A.P.; Holman, T.R.; et al. Resolving the paradox of ferroptotic cell death: Ferrostatin-1 binds to 15LOX/PEBP1 complex, suppresses generation of peroxidized ETE-PE, and protects against ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2021, 38, 101744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naderi, S.; Motamedi, F.; Pourbadie, H.G.; Rafiei, S.; Khodagholi, F.; Naderi, N.; Janahmadi, M. Neuroprotective Effects of Ferrostatin and Necrostatin Against Entorhinal Amyloidopathy-Induced Electrophysiological Alterations Mediated by voltage-gated Ca(2+) Channels in the Dentate Gyrus Granular Cells. Neurochem. Res. 2024, 49, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Madungwe, N.B.; Imam Aliagan, A.D.; Tombo, N.; Bopassa, J.C. Liproxstatin-1 protects the mouse myocardium against ischemia/reperfusion injury by decreasing VDAC1 levels and restoring GPX4 levels. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 520, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Ling, X.; Chen, T.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, J.; Huang, L.; Lin, X.; Lin, L. Inhibition of Hippocampal Neuronal Ferroptosis by Liproxstatin-1 Improves Learning and Memory Function in Aged Mice with Perioperative Neurocognitive Dysfunction. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 2991–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negida, A.; Hassan, N.M.; Aboeldahab, H.; Zain, Y.E.; Negida, Y.; Cadri, S.; Cadri, N.; Cloud, L.J.; Barrett, M.J.; Berman, B. Efficacy of the iron-chelating agent, deferiprone, in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr, A.C.; Xiong, M.P. Challenges and Opportunities of Deferoxamine Delivery for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease, Parkinson’s Disease, and Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Sun, L.; Chen, X.; Zhang, D. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and neurodegenerative diseases. Neural Regen. Res. 2013, 8, 2003–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskirchen, R. Comprehensive Pharmacological Management of Wilson’s Disease: Mechanisms, Clinical Strategies, and Emerging Therapeutic Innovations. Science 2025, 7, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, K.M.; Kaushal, J.B.; Takkar, S.; Sharma, G.; Alsafwani, Z.W.; Pothuraju, R.; Batra, S.K.; Siddiqui, J.A. Copper metabolism and cuproptosis in human malignancies: Unraveling the complex interplay for therapeutic insights. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Lv, X.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J. Indexes of ferroptosis and iron metabolism were associated with the severity of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1297166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nulianti, R.; Bayuaji, H.; Ritonga, M.A.; Djuwantono, T.; Tjahyadi, D.; Rachmawati, A.; Dwiningsih, S.R.; Nisa, A.S.; Adriansyah, P.N.A. Correlation of ferritin and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) level as a marker of ferroptosis process in endometrioma. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda, N.; Fernandez-Cao, J.C.; Tous, M.; Arija, V. Increased iron levels and lipid peroxidation in a Mediterranean population of Spain. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 46, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Kang, H.; Rao, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wei, L. Metal-phenolic nanozyme as a ferroptosis inhibitor for alleviating cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1535969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morioka, S.; Maueröder, C.; Ravichandran, K.S. Living on the Edge: Efferocytosis at the Interface of Homeostasis and Pathology. Immunity 2019, 50, 1149–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, V.; Sundaresan, A.; Shishodia, S. Overnutrition and Lipotoxicity: Impaired Efferocytosis and Chronic Inflammation as Precursors to Multifaceted Disease Pathogenesis. Biology 2024, 13, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochreiter-Hufford, A.; Ravichandran, K.S. Clearing the dead: Apoptotic cell sensing, recognition, engulfment, and digestion. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a008748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchin, A.Y.; Ogmen, A.; Blagodatski, A.S.; Egorova, A.; Batin, M.; Glinin, T. Targeting multiple hallmarks of mammalian aging with combinations of interventions. Aging 2024, 16, 12073–12100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliev, T.; Singh, P.B. Targeting Senescence: A Review of Senolytics and Senomorphics in Anti-Aging Interventions. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian-Valverde, M.; Pasinetti, G.M. The NLRP3 Inflammasome as a Critical Actor in the Inflammaging Process. Cells 2020, 9, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursini, F.; Maiorino, M. Lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis: The role of GSH and GPx4. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 152, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżowska, A.; Brown, J.; Xu, H.; Sataranatarajan, K.; Kinter, M.; Tyrell, V.J.; O’Donnell, V.B.; Van Remmen, H. Elevated phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (GPX4) expression modulates oxylipin formation and inhibits age-related skeletal muscle atrophy and weakness. Redox Biol. 2023, 64, 102761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, G.; Singh, S.; Singh, A.K.; Rizvi, S.I. N-acetyl-l-cysteine attenuates oxidative damage and neurodegeneration in rat brain during aging. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 96, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, D.A.; Zabrecky, G.; Kremens, D.; Liang, T.W.; Wintering, N.A.; Cai, J.; Wei, X.; Bazzan, A.J.; Zhong, L.; Bowen, B.; et al. N-Acetyl Cysteine May Support Dopamine Neurons in Parkinson’s Disease: Preliminary Clinical and Cell Line Data. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulug, B.; Altay, O.; Li, X.; Hanoglu, L.; Cankaya, S.; Lam, S.; Velioglu, H.A.; Yang, H.; Coskun, E.; Idil, E.; et al. Combined metabolic activators improve cognitive functions in Alzheimer’s disease patients: A randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase-II trial. Transl. Neurodegener. 2023, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, K.; Takahashi, M.; Oh-Hashi, K.; Ando, K.; Hirata, Y. Quercetin and resveratrol inhibit ferroptosis independently of Nrf2-ARE activation in mouse hippocampal HT22 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 172, 113586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Yin, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, X.; Liu, C.; Luo, Y.; Luo, J.; He, J.; Yu, B.; Wang, Q.; et al. EGCG Alleviates DSS-Induced Colitis by Inhibiting Ferroptosis Through the Activation of the Nrf2-GPX4 Pathway and Enhancing Iron Metabolism. Nutrients 2025, 17, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Zhang, A.; Lv, D.; Cong, L.; Sun, Z.; Liu, L. EGCG activates Keap1/P62/Nrf2 pathway, inhibits iron deposition and apoptosis in rats with cerebral hemorrhage. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainey, N.E.; Moustapha, A.; Saric, A.; Nicolas, G.; Sureau, F.; Petit, P.X. Iron chelation by curcumin suppresses both curcumin-induced autophagy and cell death together with iron overload neoplastic transformation. Cell Death Discov. 2019, 5, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Yuan, J.; Yang, Q.; Tu, Q.; Yu, H.; Chu, L.; Tang, L.; Zhang, C. Curcumin-polydopamine nanoparticles alleviate ferroptosis by iron chelation and inhibition of oxidative stress damage. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 14934–14941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Shaohuan, Q.; Pinfang, K.; Chao, S. Curcumin Attenuates Ferroptosis-Induced Myocardial Injury in Diabetic Cardiomyopathy through the Nrf2 Pathway. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2022, 2022, 3159717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Jia, Z.; Wang, J.; Huang, S.; Yang, S.; Xiao, S.; Xia, D.; Zhou, Y. Curcumin reverses erastin-induced chondrocyte ferroptosis by upregulating Nrf2. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M.; Proneth, B. Selenium: Tracing Another Essential Element of Ferroptotic Cell Death. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lou, H.; Ou, Z.; Liu, J.; Duan, W.; Wang, H.; Ge, Y.; Min, J.; Wang, F.; et al. GPX4 and vitamin E cooperatively protect hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells from lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jin, D.; Zhou, S.; Dong, N.; Ji, Y.; An, P.; Wang, J.; Luo, Y.; Luo, J. Regulatory roles of copper metabolism and cuproptosis in human cancers. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1123420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, P.; Moorthy, H.; Ramesh, M.; Padhi, D.; Govindaraju, T. A natural polyphenol activates and enhances GPX4 to mitigate amyloid-β induced ferroptosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 9427–9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magtanong, L.; Ko, P.J.; To, M.; Cao, J.Y.; Forcina, G.C.; Tarangelo, A.; Ward, C.C.; Cho, K.; Patti, G.J.; Nomura, D.K.; et al. Exogenous Monounsaturated Fatty Acids Promote a Ferroptosis-Resistant Cell State. Cell Chem. Biol. 2019, 26, 420–432.e429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickles, S.; Vigié, P.; Youle, R.J. Mitophagy and Quality Control Mechanisms in Mitochondrial Maintenance. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R170–R185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosef, R.; Pilpel, N.; Papismadov, N.; Gal, H.; Ovadya, Y.; Vadai, E.; Miller, S.; Porat, Z.; Ben-Dor, S.; Krizhanovsky, V. p21 maintains senescent cell viability under persistent DNA damage response by restraining JNK and caspase signaling. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 2280–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]