Integrative Genomic and AI Approaches to Lung Cancer and Implications for Disease Prevention in Former Smokers

Abstract

1. Introduction

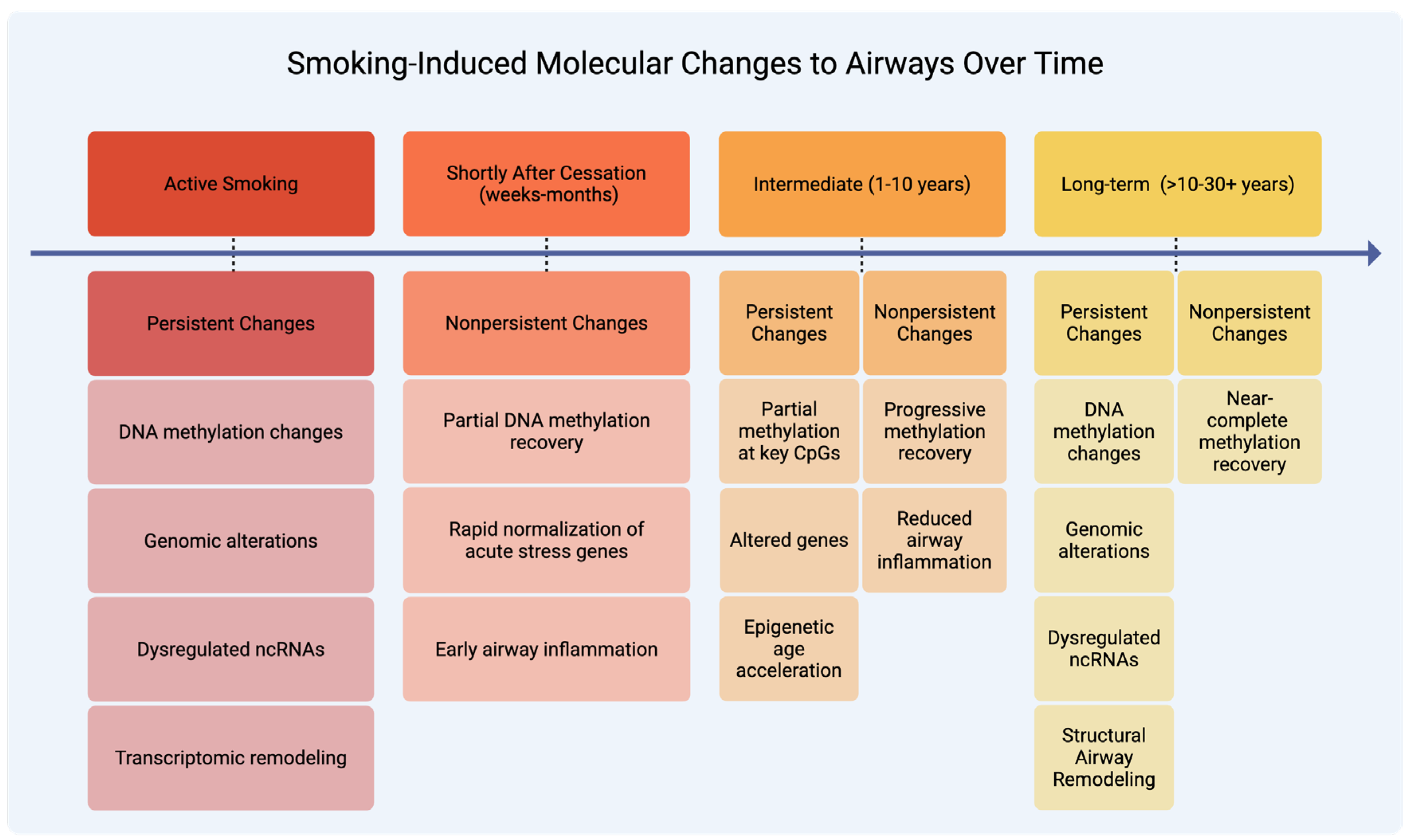

2. Smoking-Induced Molecular Changes

2.1. Nonpersistent Molecular Changes

2.1.1. Transcriptomic and Functional Recovery

2.1.2. Epigenetic and microRNA Recovery

2.2. Persistent Molecular Changes

2.2.1. Genetic Alterations

2.2.2. Gene Expression and Regulatory Changes

2.2.3. Epigenetic Modifications

2.2.4. Immune and Structural Consequences

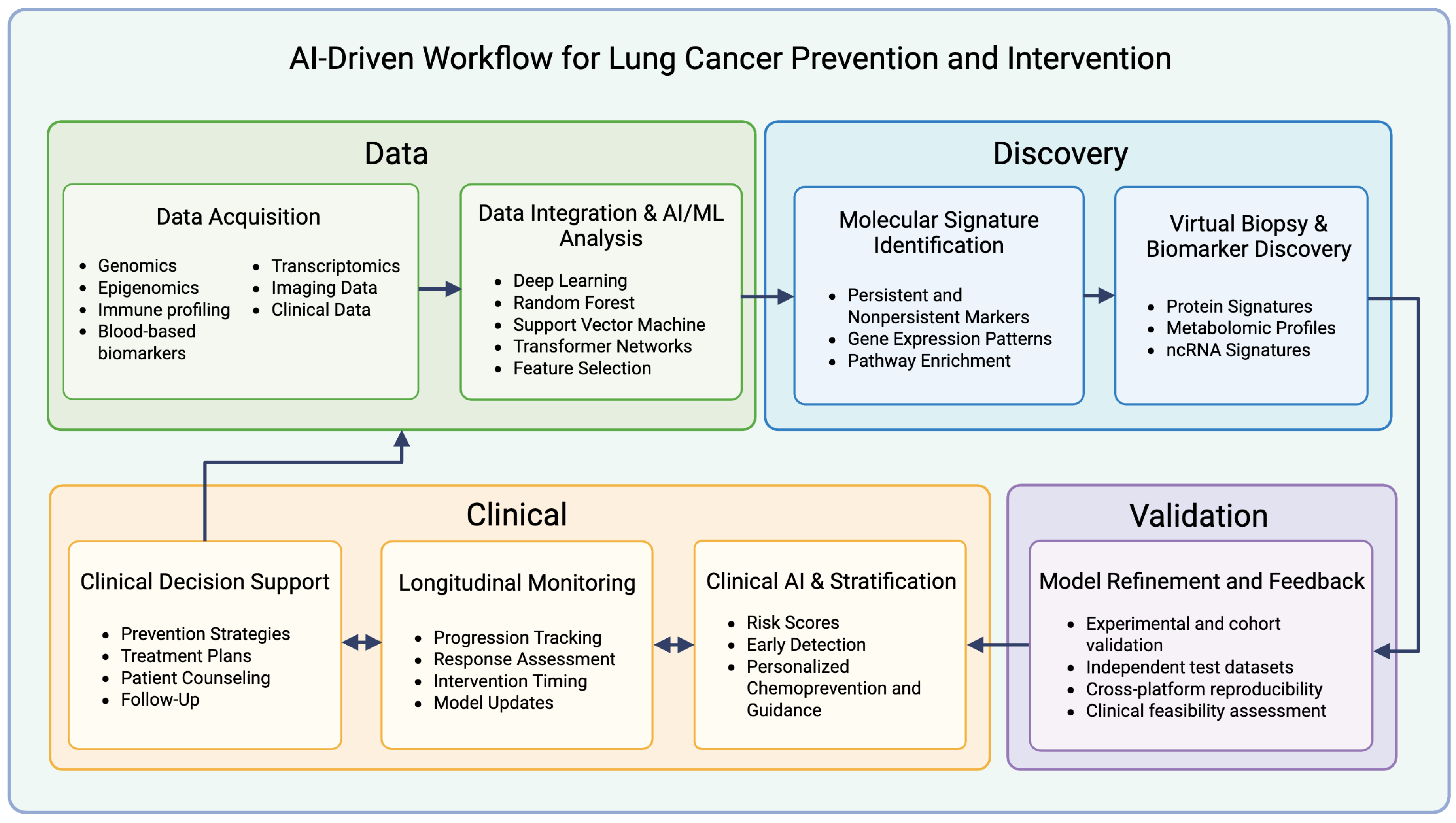

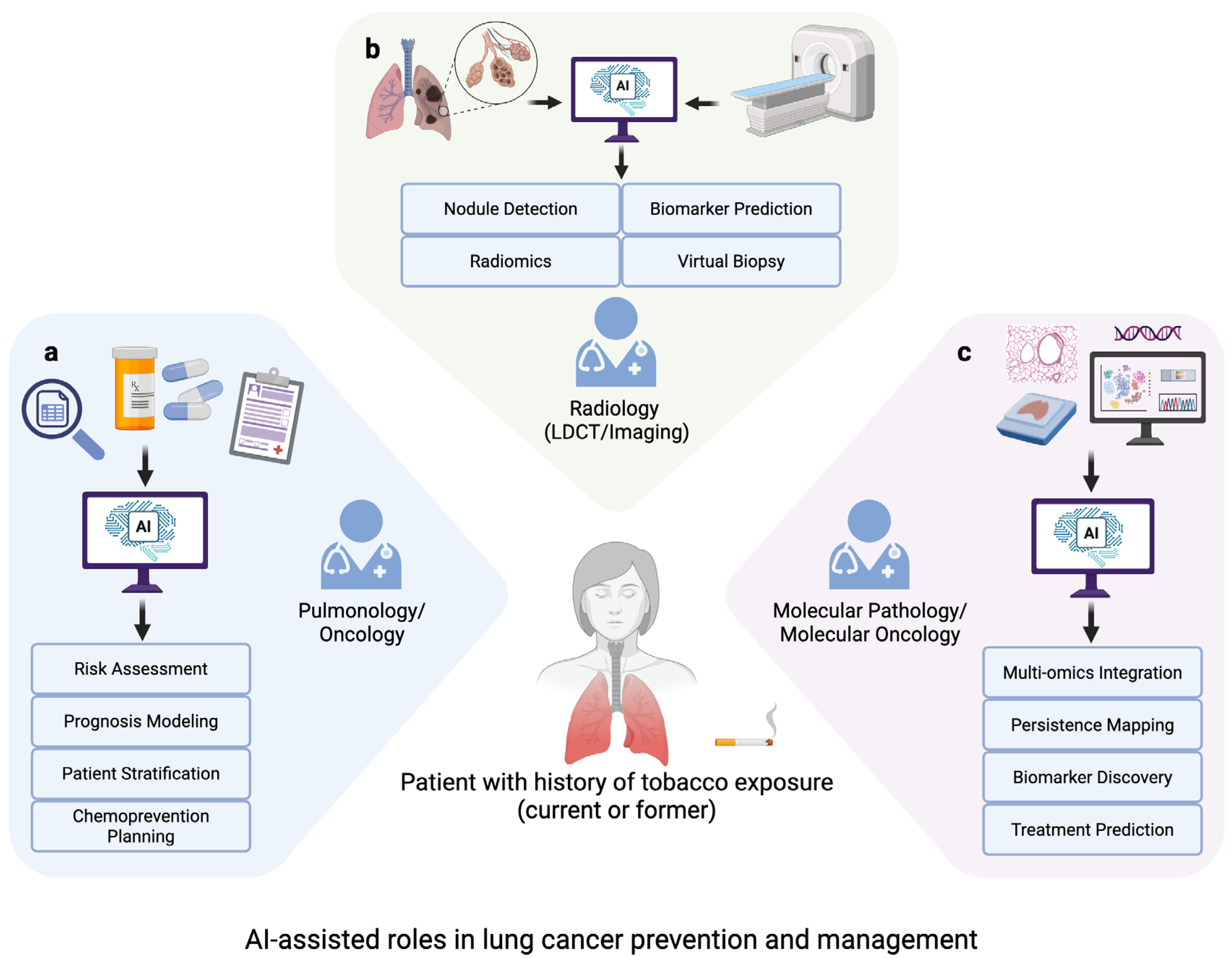

3. Role of AI in Advancing Strategies for Prevention and Intervention

3.1. Identifying Molecular Signatures

3.2. Integration of Multi-Omics Data

3.3. Acceleration of Biomarker Development and “Virtual Biopsies”

4. Limitations, Generalizability, and Future Directions

4.1. Cohort Heterogeneity and Generalizability

4.2. Interpretation, Causality, and Clinical Relevance

4.3. Technical and Methodological Constraints of AI Models

4.4. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5hmC | 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine |

| 5mC | 5-Methylcytosine |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AHRR | Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Repressor |

| ALDH | Aldehyde Dehydrogenase |

| CDKN2A/p16 | Cyclin Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2A |

| cHCC-CCA | Combined Hepatocellular-Cholangiocarcinoma |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CpG | Cytosine–Phosphate–Guanine Dinucleotide |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| EMR | Electronic Medical Record |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| EWAS | Epigenome-Wide Association Study |

| F2RL3 | Coagulation Factor II (Thrombin) Receptor-Like 3 |

| FHIT | Fragile Histidine Triad |

| GATK | Genome Analysis Toolkit |

| GDC | Genomic Data Commons |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| IARC | International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| IGV | Integrative Genomics Viewer |

| IPA | Ingenuity Pathway Analysis |

| KRAS | Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog |

| LDCT | Low-Dose Computed Tomography |

| LIDC-IDRI | Lung Image Database Consortium – Image Database Resource Initiative |

| LOH | Loss of Heterozygosity |

| LUNA16 | Lung Nodule Analysis 2016 Dataset |

| LUAD | Lung Adenocarcinoma |

| LUSC | Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| MCCS | Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MOFA+ | Multi-Omics Factor Analysis Plus |

| MONAI | Medical Open Network for Artificial Intelligence |

| ncRNA | Noncoding RNA |

| NNK | 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone |

| NOWAC | Norwegian Women and Cancer Study |

| NSCLC | Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer |

| NSHDS | Northern Sweden Health and Disease Study |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PAH | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| PLCOm2012 | Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial 2012 Risk Prediction Model |

| QC | Quality Control |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| SCLC | Small-Cell Lung Cancer |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TP53 | Tumor Protein p53 |

| U-Net | Convolutional Neural Network Architecture for Biomedical Image Segmentation |

| WGCNA | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2025; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2025; Available online: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2025/2025-cancer-facts-and-figures-acs.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Pesch, B.; Kendzia, B.; Gustavsson, P.; Jöckel, K.; Johnen, G.; Pohlabeln, H.; Olsson, A.; Ahrens, W.; Gross, I.M.; Brüske, I.; et al. Cigarette smoking and lung cancer—Relative risk estimates for the major histological types from a pooled analysis of case–control studies. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 131, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, H.S.; Chiang, A.C. Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2025, 333, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Lung Cancer. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lung-cancer (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Report on Trends in Prevalence of Tobacco Use 2000–2030; Report No.: 978-92-4-008828-3; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–128. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240088283 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Reitsma, M.; Kendrick, P.; Anderson, J.; Arian, N.; Feldman, R.; Gakidou, E.; Gupta, V. Reexamining Rates of Decline in Lung Cancer Risk after Smoking Cessation. A Meta-analysis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2020, 17, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, K.K.; Rahman, B.; Ayers, C.K.; Relevo, R.; Griffin, J.C.; Halpern, M.T. Lung cancer diagnosis and mortality beyond 15 years since quit in individuals with a 20+ pack-year history: A systematic review. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 84–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipollina, C.; Bruno, A.; Fasola, S.; Cristaldi, M.; Patella, B.; Inguanta, R.; Vilasi, A.; Aiello, G.; La Grutta, S.; Torino, C.; et al. Cellular and Molecular Signatures of Oxidative Stress in Bronchial Epithelial Cell Models Injured by Cigarette Smoke Extract. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kode, A.; Yang, S.-R.; Rahman, I. Differential effects of cigarette smoke on oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokine release in primary human airway epithelial cells and in a variety of transformed alveolar epithelial cells. Respir. Res. 2006, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halvorsen, A.R.; Silwal-Pandit, L.; Meza-Zepeda, L.A.; Vodak, D.; Vu, P.; Sagerup, C.; Hovig, E.; Myklebost, O.; Børresen-Dale, A.-L.; Brustugun, O.T.; et al. TP53 Mutation Spectrum in Smokers and Never Smoking Lung Cancer Patients. Front. Genet. 2016, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeifer, G.P.; Denissenko, M.F.; Olivier, M.; Tretyakova, N.; Hecht, S.S.; Hainaut, P. Tobacco smoke carcinogens, DNA damage and p53 mutations in smoking-associated cancers. Oncogene 2002, 21, 7435–7451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, D.L.; Byers, L.A.; Kurie, J.M. Smoking, p53 mutation, and lung cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. MCR 2014, 12, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarmalaite, S.; Kannio, A.; Anttila, S.; Lazutka, J.R.; Husgafvel-Pursiainen, K. Aberrant p16 promoter methylation in smokers and former smokers with nonsmall cell lung cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 106, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US); Office on Smoking and Health (US). How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease; Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-16-084078-4. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53017/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Moghaddam, S.J.; Savai, R.; Salehi-Rad, R.; Sengupta, S.; Kammer, M.N.; Massion, P.; Beane, J.E.; Ostrin, E.J.; Priolo, C.; Tennis, M.A.; et al. Premalignant Progression in the Lung: Knowledge Gaps and Novel Opportunities for Interception of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. An Official American Thoracic Society Research Statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 210, 548–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strulovici-Barel, Y.; Rostami, M.R.; Kaner, R.J.; Mezey, J.G.; Crystal, R.G. Serial Sampling of the Small Airway Epithelium to Identify Persistent Smoking-dysregulated Genes. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 208, 780–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Leung, H.; Khan, K.M.F.; Miller, C.G.; Subbaramaiah, K.; Falcone, D.J.; Dannenberg, A.J. Tobacco Smoke Induces Urokinase-Type Plasminogen Activator and Cell Invasiveness: Evidence for an Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor–Dependent Mechanism. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 8966–8972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadara, H.; Wistuba, I.I. Field Cancerization in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer: Implications in Disease Pathogenesis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2012, 9, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korde, A.; Ramaswamy, A.; Anderson, S.; Jin, L.; Zhang, J.; Hu, B.; Velasco, W.V.; Diao, L.; Wang, J.; Pisani, M.A.; et al. Cigarette smoke induces angiogenic activation in the cancer field through dysregulation of an endothelial microRNA. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Begum, R.; Thota, S.; Batra, S. A systematic review of smoking-related epigenetic alterations. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 2715–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spira, A.; Beane, J.; Shah, V.; Liu, G.; Schembri, F.; Yang, X.; Palma, J.; Brody, J.S. Effects of cigarette smoke on the human airway epithelial cell transcriptome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 10143–10148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beane, J.; Sebastiani, P.; Liu, G.; Brody, J.S.; Lenburg, M.E.; Spira, A. Reversible and permanent effects of tobacco smoke exposure on airway epithelial gene expression. Genome Biol. 2007, 8, R201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, R.L.; Miller, Y.E. Lung cancer chemoprevention: Current status and future prospects. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 10, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshkhah, A.; Prabhala, S.; Viswanathan, P.; Subramanian, H.; Lin, J.; Chang, A.S.; Bharat, A.; Roy, H.K.; Backman, V. Early detection of lung cancer using artificial intelligence-enhanced optical nanosensing of chromatin alterations in field carcinogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, E.; Muneer, A.; Zhang, J.; Xia, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, C.; Heymach, J.V.; Wu, J.; Le, X. Progress and challenges of artificial intelligence in lung cancer clinical translation. npj Precis. Oncol. 2025, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çalışkan, M.; Tazaki, K. AI/ML advances in non-small cell lung cancer biomarker discovery. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1260374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prelaj, A.; Miskovic, V.; Zanitti, M.; Trovo, F.; Genova, C.; Viscardi, G.; Rebuzzi, S.E.; Mazzeo, L.; Provenzano, L.; Kosta, S.; et al. Artificial intelligence for predictive biomarker discovery in immuno-oncology: A systematic review. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 29–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Toxicology Program, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Report on Carcinogens, 15th ed.; Public Health Service; National Toxicology Program: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2021. Available online: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/research/assessments/cancer/roc (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Office on Smoking and Health (US). The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General; Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2006. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44324/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Office of the Surgeon General (US); Office on Smoking and Health (US). The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General; Reports of the Surgeon General; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2004. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44695/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK179276/ (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- National Cancer Institute (U.S.). Harms of Cigarette Smoking and Health Benefits of Quitting. 2017. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/tobacco/cessation-fact-sheet#:~:text=,Formaldehyde (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Jha, P.; Ramasundarahettige, C.; Landsman, V.; Rostron, B.; Thun, M.; Anderson, R.N.; McAfee, T.; Peto, R. 21st-Century Hazards of Smoking and Benefits of Cessation in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tindle, H.A.; Stevenson Duncan, M.; Greevy, R.A.; Vasan, R.S.; Kundu, S.; Massion, P.P.; Freiberg, M.S. Lifetime Smoking History and Risk of Lung Cancer: Results from the Framingham Heart Study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 1201–1207, Erratum in J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, R.; Peto, R.; Boreham, J.; Sutherland, I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ 2004, 328, 1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.; Wahl, S.; Pfeiffer, L.; Ward-Caviness, C.K.; Kunze, S.; Kretschmer, A.; Reischl, E.; Peters, A.; Gieger, C.; Waldenberger, M. The dynamics of smoking-related disturbed methylation: A two time-point study of methylation change in smokers, non-smokers and former smokers. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, F.; Sandanger, T.M.; Castagné, R.; Campanella, G.; Polidoro, S.; Palli, D.; Krogh, V.; Tumino, R.; Sacerdote, C.; Panico, S.; et al. Dynamics of smoking-induced genome-wide methylation changes with time since smoking cessation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 2349–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopack, E.T.; Carroll, J.E.; Cole, S.W.; Seeman, T.E.; Crimmins, E.M. Lifetime exposure to smoking, epigenetic aging, and morbidity and mortality in older adults. Clin. Epigenet. 2022, 14, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Wan, E.; Morrow, J.; Cho, M.H.; Crapo, J.D.; Silverman, E.K.; DeMeo, D.L. The impact of genetic variation and cigarette smoke on DNA methylation in current and former smokers from the COPDGene study. Epigenetics 2015, 10, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.K.; Pausova, Z. Cigarette smoking and DNA methylation. Front. Genet. 2013, 4, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khulan, B.; Ye, K.; Shi, M.K.; Waldman, S.; Marsh, A.; Siddiqui, T.; Okorozo, A.; Desai, A.; Patel, D.; Dobkin, J.; et al. Normal bronchial field basal cells show persistent methylome-wide impact of tobacco smoking, including in known cancer genes. Epigenetics 2025, 20, 2466382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Lee, J.S.; Kurie, J.M.; Fan, Y.H.; Lippman, S.M.; Broxson, A.; Khuri, F.R.; Hong, W.K.; Lee, J.J.; Yu, R.; et al. Clonal Genetic Alterations in the Lungs of Current and Former Smokers. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1997, 89, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strulovici-Barel, Y.; Omberg, L.; O’Mahony, M.; Gordon, C.; Hollmann, C.; Tilley, A.E.; Salit, J.; Mezey, J.; Harvey, B.-G.; Crystal, R.G. Threshold of biologic responses of the small airway epithelium to low levels of tobacco smoke. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 182, 1524–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Lee, J.J.; Tang, H.; Fan, Y.-H.; Xiao, L.; Ren, H.; Kurie, J.; Morice, R.C.; Hong, W.K.; Mao, L. Impact of smoking cessation on global gene expression in the bronchial epithelium of chronic smokers. Cancer Prev. Res. 2008, 1, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijazi, K.; Malyszko, B.; Steiling, K.; Xiao, X.; Liu, G.; Alekseyev, Y.O.; Dumas, Y.-M.; Hertsgaard, L.; Jensen, J.; Hatsukami, D.; et al. Tobacco-Related Alterations in Airway Gene Expression are Rapidly Reversed Within Weeks Following Smoking-Cessation. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, J.; Nie, X.; Qi, Y.; Zhou, J.; Qi, Y. Short-term smoking cessation leads to a universal decrease in whole blood genomic DNA methylation in patients with a smoking history. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 21, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braber, S.; Henricks, P.A.J.; Nijkamp, F.P.; Kraneveld, A.D.; Folkerts, G. Inflammatory changes in the airways of mice caused by cigarette smoke exposure are only partially reversed after smoking cessation. Respir. Res. 2010, 11, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, R.; Lonergan, K.M.; Ng, R.T.; MacAulay, C.; Lam, W.L.; Lam, S. Effect of active smoking on the human bronchial epithelium transcriptome. BMC Genom. 2007, 8, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, A.M.; Soldi, R.; Anderlind, C.; Scholand, M.B.; Qian, J.; Zhang, X.; Cooper, K.; Walker, D.; McWilliams, A.; Liu, G.; et al. Airway PI3K Pathway Activation Is an Early and Reversible Event in Lung Cancer Development. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010, 2, 26ra25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshawarz, A.; Joehanes, R.; Guan, W.; Huan, T.; DeMeo, D.L.; Grove, M.L.; Fornage, M.; Levy, D.; O’Connor, G. Longitudinal change in blood DNA epigenetic signature after smoking cessation. Epigenetics 2022, 17, 1098–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, J.M.; Jansen, R.; Brooks, A.; Willemsen, G.; van Grootheest, G.; de Geus, E.; Smit, J.H.; Penninx, B.W.; Boomsma, D.I. Differential gene expression patterns between smokers and non-smokers: Cause or consequence? Addict. Biol. 2017, 22, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, R.; Strulovici-Barel, Y.; Salit, J.; Staudt, M.R.; Ahmed, J.; Tilley, A.E.; Yee-Levin, J.; Hollmann, C.; Harvey, B.-G.; et al. Persistence of smoking-induced dysregulation of miRNA expression in the small airway epithelium despite smoking cessation. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Gowers, K.H.C.; Lee-Six, H.; Chandrasekharan, D.P.; Coorens, T.; Maughan, E.F.; Beal, K.; Menzies, A.; Millar, F.R.; Anderson, E.; et al. Tobacco smoking and somatic mutations in human bronchial epithelium. Nature 2020, 578, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.-L.; Yang, J.; Gomi, K.; Chao, I.; Crystal, R.G.; Shaykhiev, R. EGF-Amphiregulin Interplay in Airway Stem/Progenitor Cells Links the Pathogenesis of Smoking-Induced Lesions in the Human Airway Epithelium. Stem Cells 2017, 35, 824–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vucic, E.A.; Thu, K.L.; Pikor, L.A.; Enfield, K.S.S.; Yee, J.; English, J.C.; MacAulay, C.E.; Lam, S.; Jurisica, I.; Lam, W.L. Smoking status impacts microRNA mediated prognosis and lung adenocarcinoma biology. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeilinger, S.; Kühnel, B.; Klopp, N.; Baurecht, H.; Kleinschmidt, A.; Gieger, C.; Weidinger, S.; Lattka, E.; Adamski, J.; Peters, A.; et al. Tobacco Smoking Leads to Extensive Genome-Wide Changes in DNA Methylation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e63812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, J.M.; Ribeiro, R.; Soldatkina, O.; Moraes, A.; García-Pérez, R.; Oliveros, W.; Ferreira, P.G.; Melé, M. The molecular impact of cigarette smoking resembles aging across tissues. Genome Med. 2025, 17, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasanelli, F.; Baglietto, L.; Ponzi, E.; Guida, F.; Campanella, G.; Johansson, M.; Grankvist, K.; Johansson, M.; Assumma, M.B.; Naccarati, A.; et al. Hypomethylation of smoking-related genes is associated with future lung cancer in four prospective cohorts. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Huang, Q.; Javed, R.; Zhong, J.; Gao, H.; Liang, H. Effect of tobacco smoking on the epigenetic age of human respiratory organs. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruse, S.; Petersen, H.; Weissfeld, J.; Picchi, M.; Willink, R.; Do, K.; Siegfried, J.; Belinsky, S.A.; Tesfaigzi, Y. Increased methylation of lung cancer-associated genes in sputum DNA of former smokers with chronic mucous hypersecretion. Respir. Res. 2014, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Biase, M.S.; Massip, F.; Wei, T.-T.; Giorgi, F.M.; Stark, R.; Stone, A.; Gladwell, A.; O’Reilly, M.; Schütte, D.; de Santiago, I.; et al. Smoking-associated gene expression alterations in nasal epithelium reveal immune impairment linked to lung cancer risk. Genome Med. 2024, 16, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cunto, G.; De Meo, S.; Bartalesi, B.; Cavarra, E.; Lungarella, G.; Lucattelli, M. Smoking Cessation in Mice Does Not Switch off Persistent Lung Inflammation and Does Not Restore the Expression of HDAC2 and SIRT1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-André, V.; Charbit, B.; Biton, A.; Rouilly, V.; Possémé, C.; Bertrand, A.; Rotival, M.; Bergstedt, J.; Patin, E.; Albert, M.L.; et al. Smoking changes adaptive immunity with persistent effects. Nature 2024, 626, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapla, D.; Chorya, H.P.; Ishfaq, L.; Khan, A.; Vr, S.; Garg, S. An Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Integrated Approach to Enhance Early Detection and Personalized Treatment Strategies in Lung Cancer Among Smokers: A Literature Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e66688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladbury, C.; Amini, A.; Govindarajan, A.; Mambetsariev, I.; Raz, D.J.; Massarelli, E.; Williams, T.; Rodin, A.; Salgia, R. Integration of artificial intelligence in lung cancer: Rise of the machine. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard, M.; Scott-Boyer, M.-P.; Bodein, A.; Périn, O.; Droit, A. Integration strategies of multi-omics data for machine learning analysis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 3735–3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Che, Y.; Liu, R.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W. Deep learning–driven multi-omics analysis: Enhancing cancer diagnostics and therapeutics. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, I.; Verma, S.; Kumar, S.; Jere, A.; Anamika, K. Multi-omics Data Integration, Interpretation, and Its Application. Bioinforma. Biol. Insights 2020, 14, 1177932219899051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, R.L.; Heath, A.P.; Ferretti, V.; Varmus, H.E.; Lowy, D.R.; Kibbe, W.A.; Staudt, L.M. Toward a Shared Vision for Cancer Genomic Data. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1109–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczak, K.; Czerwińska, P.; Wiznerowicz, M. Review The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): An immeasurable source of knowledge. Współczesna Onkol. 2015, 1A, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setio, A.A.A.; Traverso, A.; De Bel, T.; Berens, M.S.N.; Bogaard, C.V.D.; Cerello, P.; Chen, H.; Dou, Q.; Fantacci, M.E.; Geurts, B.; et al. Validation, comparison, and combination of algorithms for automatic detection of pulmonary nodules in computed tomography images: The LUNA16 challenge. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armato, S.G.; McLennan, G.; Bidaut, L.; McNitt-Gray, M.F.; Meyer, C.R.; Reeves, A.P.; Zhao, B.; Aberle, D.R.; Henschke, C.I.; Hoffman, E.A.; et al. The Lung Image Database Consortium (LIDC) and Image Database Resource Initiative (IDRI): A Completed Reference Database of Lung Nodules on CT Scans. Med. Phys. 2011, 38, 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, D.R.; Balasubramanian, S.; Swerdlow, H.P.; Smith, G.P.; Milton, J.; Brown, C.G.; Hall, K.P.; Evers, D.J.; Barnes, C.L.; Bignell, H.R.; et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature 2008, 456, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.; Holmes, N.; Clarke, T.; Munro, R.; Debebe, B.J.; Loose, M. Readfish enables targeted nanopore sequencing of gigabase-sized genomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, T.; Mars, K.; Young, G.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Karalius, J.W.; Landolin, J.M.; Maurer, N.; Kudrna, D.; Hardigan, M.A.; Steiner, C.C.; et al. Highly accurate long-read HiFi sequencing data for five complex genomes. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illumina, Inc. An Introduction to the Illumina 5-Base Solution. 2025. Available online: https://www.illumina.com/science/genomics-research/articles/5-base-solution.html (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; De Bakker, P.I.W.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A Tool Set for Whole-Genome Association and Population-Based Linkage Analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardila, D.; Kiraly, A.P.; Bharadwaj, S.; Choi, B.; Reicher, J.J.; Peng, L.; Tse, D.; Etemadi, M.; Ye, W.; Corrado, G.; et al. End-to-end lung cancer screening with three-dimensional deep learning on low-dose chest computed tomography. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 954–961, Erratum in Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhael, P.G.; Wohlwend, J.; Yala, A.; Karstens, L.; Xiang, J.; Takigami, A.K.; Bourgouin, P.P.; Chan, P.; Mrah, S.; Amayri, W.; et al. Sybil: A Validated Deep Learning Model to Predict Future Lung Cancer Risk from a Single Low-Dose Chest Computed Tomography. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 2191–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; ACM: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2939672.2939785 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Tammemägi, M.C.; Katki, H.A.; Hocking, W.G.; Church, T.R.; Caporaso, N.; Kvale, P.A.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Silvestri, G.A.; Riley, T.L.; Commins, J.; et al. Selection Criteria for Lung-Cancer Screening. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 728–736, Erratum in N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Cui, G.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Sun, M. Graph neural networks: A review of methods and applications. AI Open 2021, 1, 57–81, Erratum in AI Open 2025, 6, 331–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates, Inc.: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 5998–6008. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.J.; Kinahan, P.E.; Hricak, H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology 2016, 278, 563–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argelaguet, R.; Arnol, D.; Bredikhin, D.; Deloro, Y.; Velten, B.; Marioni, J.C.; Stegle, O. MOFA+: A statistical framework for comprehensive integration of multi-modal single-cell data. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohart, F.; Gautier, B.; Singh, A.; Lê Cao, K.-A. mixOmics: An R package for ’omics feature selection and multiple data integration. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, F.W.; Ozerov, I.V.; Zhavoronkov, A. AI-powered therapeutic target discovery. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 44, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamya, P.; Ozerov, I.V.; Pun, F.W.; Tretina, K.; Fokina, T.; Chen, S.; Naumov, V.; Long, X.; Lin, S.; Korzinkin, M.; et al. PandaOmics: An AI-Driven Platform for Therapeutic Target and Biomarker Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2024, 64, 3961–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, T.; Yang, L.; Yang, D.M.; Fujimoto, J.; Yi, F.; Luo, X.; Yang, Y.; Yao, B.; Lin, S.; et al. ConvPath: A software tool for lung adenocarcinoma digital pathological image analysis aided by a convolutional neural network. eBioMedicine 2019, 50, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2015, Proceedings of the 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer International Publishing: Munich, Germany, 2015; pp. 234–241. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1505.04597 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Van Griethuysen, J.J.M.; Fedorov, A.; Parmar, C.; Hosny, A.; Aucoin, N.; Narayan, V.; Beets-Tan, R.G.H.; Fillion-Robin, J.-C.; Pieper, S.; Aerts, H.J.W.L. Computational Radiomics System to Decode the Radiographic Phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, e104–e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, A.; Beichel, R.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Finet, J.; Fillion-Robin, J.-C.; Pujol, S.; Bauer, C.; Jennings, D.; Fennessy, F.; Sonka, M.; et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2012, 30, 1323–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Wu, L.; Wu, W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, Z.; Xu, M.; Gao, C. Deep learning in pulmonary nodule detection and segmentation: A systematic review. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Kim, K.H.; Singh, R.; Digumarthy, S.R.; Kalra, M.K. Validation of a Deep Learning Algorithm for the Detection of Malignant Pulmonary Nodules in Chest Radiographs. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2017135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.Y.; Williamson, D.F.K.; Chen, T.Y.; Chen, R.J.; Barbieri, M.; Mahmood, F. Data-efficient and weakly supervised computational pathology on whole-slide images. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, J.; Graham, S.; Vu, Q.D.; Jahanifar, M.; Deshpande, S.; Hadjigeorghiou, G.; Shephard, A.; Bashir, R.M.S.; Bilal, M.; Lu, W.; et al. TIAToolbox as an end-to-end library for advanced tissue image analytics. Commun. Med. 2022, 2, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorontsov, E.; Bozkurt, A.; Casson, A.; Shaikovski, G.; Zelechowski, M.; Severson, K.; Zimmermann, E.; Hall, J.; Tenenholtz, N.; Fusi, N.; et al. A foundation model for clinical-grade computational pathology and rare cancers detection. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2924–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, A.; Green, J.; Pollard, J.; Tugendreich, S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S.; et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15545–15550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Salahub, D.R.; Xu, Q.; Wang, J.; Jiang, X.; et al. A transformer-based model to predict peptide–HLA class I binding and optimize mutated peptides for vaccine design. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2022, 4, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Rao, B.; Liu, L.; Cui, L.; Xiao, G.; Su, R.; Wei, L. PepFormer: End-to-End Transformer-Based Siamese Network to Predict and Enhance Peptide Detectability Based on Sequence Only. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 6481–6490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.H.; Zhang, X.; Xin, L.; Shan, B.; Li, M. De novo peptide sequencing by deep learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8247–8252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Ye, Y.; Li, S.; Tang, H. Accurate de novo peptide sequencing using fully convolutional neural networks. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaubier, N.; Bontrager, M.; Huether, R.; Igartua, C.; Lau, D.; Tell, R.; Bobe, A.M.; Bush, S.; Chang, A.L.; Hoskinson, D.C.; et al. Integrated genomic profiling expands clinical options for patients with cancer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1351–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers, Z.R.; Connelly, C.F.; Fabrizio, D.; Gay, L.; Ali, S.M.; Ennis, R.; Schrock, A.; Campbell, B.; Shlien, A.; Chmielecki, J.; et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med. 2017, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenyuk, V.; Benson, K.; Carter, P.; Magee, D.; Zhang, J.; Bhardwaj, N.; Tae, H.; Wacker, J.; Rathi, F.; Miick, S.; et al. Clinical and analytical validation of MI Cancer Seek®, a companion diagnostic whole exome and whole transcriptome sequencing-based comprehensive molecular profiling assay. Oncotarget 2025, 16, 642–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerami, E.; Gao, J.; Dogrusoz, U.; Gross, B.E.; Sumer, S.O.; Aksoy, B.A.; Jacobsen, A.; Byrne, C.J.; Heuer, M.L.; Larsson, E.; et al. The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal: An Open Platform for Exploring Multidimensional Cancer Genomics Data. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 401–404, Erratum in Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. precisionFDA. Available online: https://precision.fda.gov/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Robinson, J.T.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Winckler, W.; Guttman, M.; Lander, E.S.; Getz, G.; Mesirov, J.P. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankhead, P.; Loughrey, M.B.; Fernández, J.A.; Dombrowski, Y.; McArt, D.G.; Dunne, P.D.; McQuaid, S.; Gray, R.T.; Murray, L.J.; Coleman, H.G.; et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, A.; Gilbert, B.; Harkes, J.; Jukic, D.; Satyanarayanan, M. OpenSlide: A vendor-neutral software foundation for digital pathology. J. Pathol. Inform. 2013, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.J.; Li, W.; Brown, R.; Ma, N.; Kerfoot, E.; Wang, Y.; Murrey, B.; Myronenko, A.; Zhao, C.; Yang, D.; et al. MONAI: An open-source framework for deep learning in healthcare. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.; Barham, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; Ghemawat, S.; Irving, G.; Isard, M.; et al. TensorFlow: A system for large-scale machine learning. arXiv 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Müller, A.; Nothman, J.; Louppe, G.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. In Proceedings of the 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 8024–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaziri-Moghadam, A.; Foroughmand-Araabi, M.-H. Integrating machine learning and bioinformatics approaches for identifying novel diagnostic gene biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Li, Z.; Jiang, T.; Yang, C.; Li, N. Artificial intelligence in lung cancer: Current applications, future perspectives, and challenges. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1486310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M.A.; Yaari, A.U.; Priebe, O.; Dietlein, F.; Loh, P.-R.; Berger, B. Genome-wide mapping of somatic mutation rates uncovers drivers of cancer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1634–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderaro, J.; Ghaffari Laleh, N.; Zeng, Q.; Maille, P.; Favre, L.; Pujals, A.; Klein, C.; Bazille, C.; Heij, L.R.; Uguen, A.; et al. Deep learning-based phenotyping reclassifies combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruily, M.; Elbashir, M.K.; Ezz, M.; Aldughayfiq, B.; Alrowaily, M.A.; Allahem, H.; Mohammed, M.; Mostafa, E.; Mostafa, A.M. Comprehensive Network Analysis of Lung Cancer Biomarkers Identifying Key Genes Through RNA-Seq Data and PPI Networks. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2025, 2025, 9994758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, M.S.; Pyo, K.-H.; Chung, J.-M.; Cho, B.C. Artificial intelligence-based non-small cell lung cancer transcriptome RNA-sequence analysis technology selection guide. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1081950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, B.D.; Ozyoruk, K.B.; Gelikman, D.G.; Harmon, S.A.; Türkbey, B. The future of multimodal artificial intelligence models for integrating imaging and clinical metadata: A narrative review. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. Ank. Turk. 2025, 31, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baião, A.R.; Cai, Z.; Poulos, R.C.; Robinson, P.J.; Reddel, R.R.; Zhong, Q.; Vinga, S.; Gonçalves, E. A technical review of multi-omics data integration methods: From classical statistical to deep generative approaches. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marra, A.; Morganti, S.; Pareja, F.; Campanella, G.; Bibeau, F.; Fuchs, T.; Loda, M.; Parwani, A.; Scarpa, A.; Reis-Filho, J.S.; et al. Artificial intelligence entering the pathology arena in oncology: Current applications and future perspectives. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, L.-J.; Weng, K.-Q.; Zhang, W.-Y.; Zhuang, Y.-N.; Li, J.; Lin, L.-M.; Chen, Y.-T.; Zeng, Y.-M. Machine learning integration with multi-omics data constructs a robust prognostic model and identifies PTGES3 as a therapeutic target for precision oncology in lung adenocarcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1651270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Ye, C.; Irkliyenko, I.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.-L.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Beadell, A.; Perea, J.; Goel, A.; et al. Ultrafast bisulfite sequencing detection of 5-methylcytosine in DNA and RNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 1559–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Rosikiewicz, W.; Pan, Z.; Jillette, N.; Wang, P.; Taghbalout, A.; Foox, J.; Mason, C.; Carroll, M.; Cheng, A.; et al. DNA methylation-calling tools for Oxford Nanopore sequencing: A survey and human epigenome-wide evaluation. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliwell, D.O.; Honig, F.; Bagby, S.; Roy, S.; Murrell, A. Double and single stranded detection of 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine with nanopore sequencing. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, W.A.; Johnson, A.F.; Rowell, W.J.; Farrow, E.; Hall, R.; Cohen, A.S.A.; Means, J.C.; Zion, T.N.; Portik, D.M.; Saunders, C.T.; et al. Direct haplotype-resolved 5-base HiFi sequencing for genome-wide profiling of hypermethylation outliers in a rare disease cohort. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.; Na, K.J. A Risk Stratification Model for Lung Cancer Based on Gene Coexpression Network and Deep Learning. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 2914280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alum, E.U. AI-driven biomarker discovery: Enhancing precision in cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, P.; Leijenaar, R.T.H.; Deist, T.M.; Peerlings, J.; De Jong, E.E.C.; Van Timmeren, J.; Sanduleanu, S.; Larue, R.T.H.M.; Even, A.J.G.; Jochems, A.; et al. Radiomics: The bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muti, H.S.; Heij, L.R.; Keller, G.; Kohlruss, M.; Langer, R.; Dislich, B.; Cheong, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-W.; Kim, H.; Kook, M.-C.; et al. Development and validation of deep learning classifiers to detect Epstein-Barr virus and microsatellite instability status in gastric cancer: A retrospective multicentre cohort study. Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e654–e664, Erratum in Lancet Digit. Health 2021, 3, e622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudray, N.; Ocampo, P.S.; Sakellaropoulos, T.; Narula, N.; Snuderl, M.; Fenyö, D.; Moreira, A.L.; Razavian, N.; Tsirigos, A. Classification and mutation prediction from non–small cell lung cancer histopathology images using deep learning. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1559–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Yang, Z.; Dai, H.; Feng, A.; Li, Q. Radiomics Study for Predicting the Expression of PD-L1 and Tumor Mutation Burden in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Based on CT Images and Clinicopathological Features. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 620246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayasa, Y.; Alajrami, D.; Idkedek, M.; Tahayneh, K.; Akar, F.A. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Lung Cancer Diagnosis and Personalized Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Workflow Step | Datasets, Models, or Platforms | Primary Role |

|---|---|---|

| Data Acquisition & Integration | TCGA/Genomic Data Commons | Large-scale multimodal genomic and clinical public datasets [70,71]. |

| LIDC-IDRI/LUNA16/EMRs | Annotated lung nodule CT datasets and electronic medical records for training and validation [72,73]. | |

| PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore Duplex, Illumina platforms | Long- and short-read sequencing for variant and methylation multi-omic profiling [74,75,76,77]. | |

| Preprocessing & QC | GATK, SAMtools | Standard pipelines for variant calling and quality-control analysis [78,79]. |

| PLINK | Genotype data management and association analysis tool [80]. | |

| Prevention & Risk Stratification | Sybil | DL model predicting lung-cancer risk from LDCT [81,82]. |

| XGBoost, PLCOm2012 | Gradient-boosting and statistical models for clinical risk prediction [83,84]. | |

| AI/ML Frameworks & Core Methods | DL architectures, Transformer Networks, Graph Neural Networks | Neural-network approaches for pattern recognition and modeling of molecular networks and pathways across multimodal data [85,86,87]. |

| Radiomics pipelines | Quantitative feature extraction from medical imaging to characterize tumor phenotypes [88]. | |

| Multi-Omics Integration & Network Analysis | WGCNA, MOFA+/mixOmics | Co-expression network and multi-omic factor analysis for integrated profiling [89,90,91]. |

| PANDAOmics | AI-driven commercial platform for drug target discovery integrating multi-omic data [92,93]. | |

| Segmentation & Image Processing | U-Net, ConvPath | Automated CT and whole-slide image segmentation with CNNs [94,95]. |

| 3D Slicer, PyRadiomics | Extraction of quantitative radiomic features from segmented regions [96,97]. | |

| Diagnosis & Lesion Detection | Lunit INSIGHT CXR | AI-based detection of pulmonary nodules and lesions in chest radiographs [98,99]. |

| Paige.AI, CLAM, TIAToolbox | AI platforms and frameworks for automated histopathological image analysis [100,101,102]. | |

| Biomarker Discovery & Pathway Analysis | QIAGEN IPA, GSEA | Pathway enrichment and functional annotation of gene signatures [103,104]. |

| clusterProfiler, Cytoscape | Functional enrichment and network visualization of molecular interactions [105,106]. | |

| DeepNovo, PepNet, PepFormer | DL tools for peptide sequencing and neoantigen discovery in immunotherapy [107,108,109,110]. | |

| Clinical Decision Support | Tempus Lens, FoundationOne CDx, Caris MI | AI-enabled decision-support platforms integrating genomic and clinical data for treatment selection [111,112,113]. |

| cBioPortal | Interactive platform for exploring multidimensional cancer-genomics data [114]. | |

| Validation & Model Refinement | PrecisionFDA | Regulatory benchmarking and reproducibility testing for genomic pipelines [115]. |

| IGV (Integrative Genomics Viewer) | Visualization tool for validation of variants and expression patterns [116]. | |

| General AI/Development Frameworks | QuPath, MONAI, OpenSlide | Open-source libraries for digital pathology and scalable image analysis [117,118,119]. |

| scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Core ML libraries for model development and deployment [120,121,122]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bénard, K.H.; Souza, V.G.P.; Stewart, G.L.; Enfield, K.S.S.; Lam, W.L. Integrative Genomic and AI Approaches to Lung Cancer and Implications for Disease Prevention in Former Smokers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 521. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010521

Bénard KH, Souza VGP, Stewart GL, Enfield KSS, Lam WL. Integrative Genomic and AI Approaches to Lung Cancer and Implications for Disease Prevention in Former Smokers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):521. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010521

Chicago/Turabian StyleBénard, Katya H., Vanessa G. P. Souza, Greg L. Stewart, Katey S. S. Enfield, and Wan L. Lam. 2026. "Integrative Genomic and AI Approaches to Lung Cancer and Implications for Disease Prevention in Former Smokers" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 521. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010521

APA StyleBénard, K. H., Souza, V. G. P., Stewart, G. L., Enfield, K. S. S., & Lam, W. L. (2026). Integrative Genomic and AI Approaches to Lung Cancer and Implications for Disease Prevention in Former Smokers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 521. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010521