Tumour-Associated MUC1 Exerts Multiple Effects on Cholesterol and Lipid Metabolism—A Potential Pathogenic Effector of Atherosclerosis in Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. TA-MUC1 Modulated the Regulation of Cholesterol and Fatty Acid Metabolism in Breast Cancer Cells

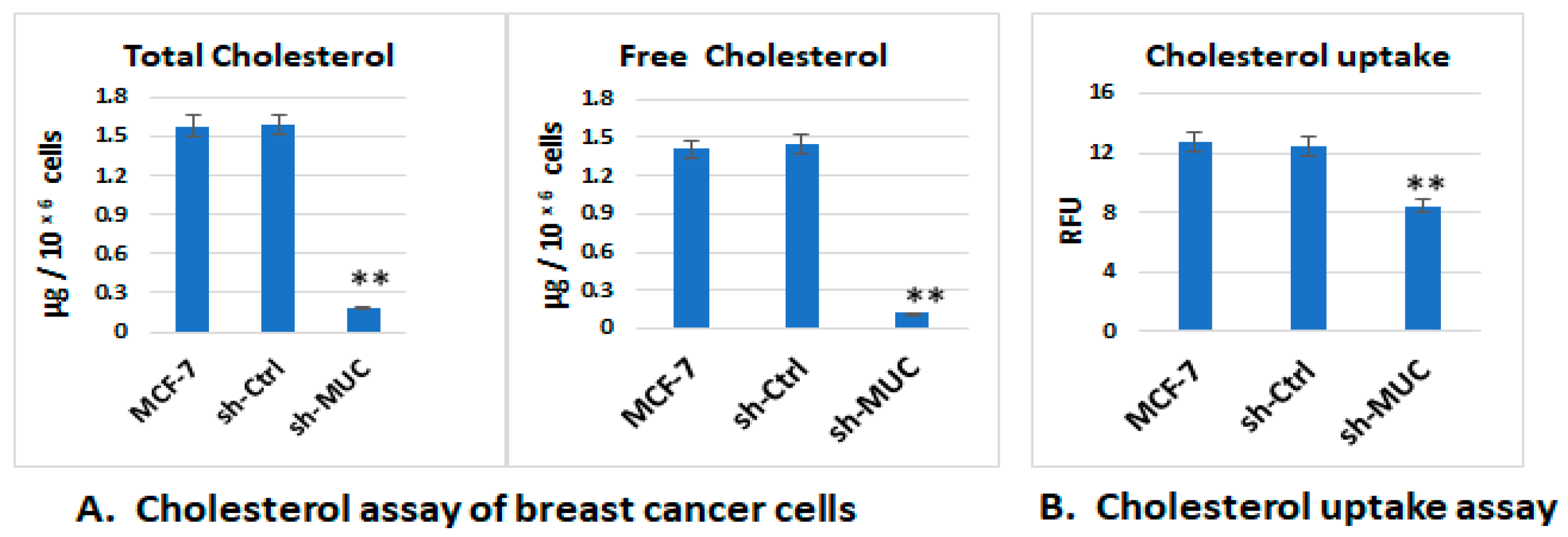

2.1.1. The Effect of TA-MUC1 on Cholesterol and Fatty Acid Metabolism Was Confirmed Using MUC1 Gene Knock down MCF-7 Cells (sh-MUC1-MCF7)

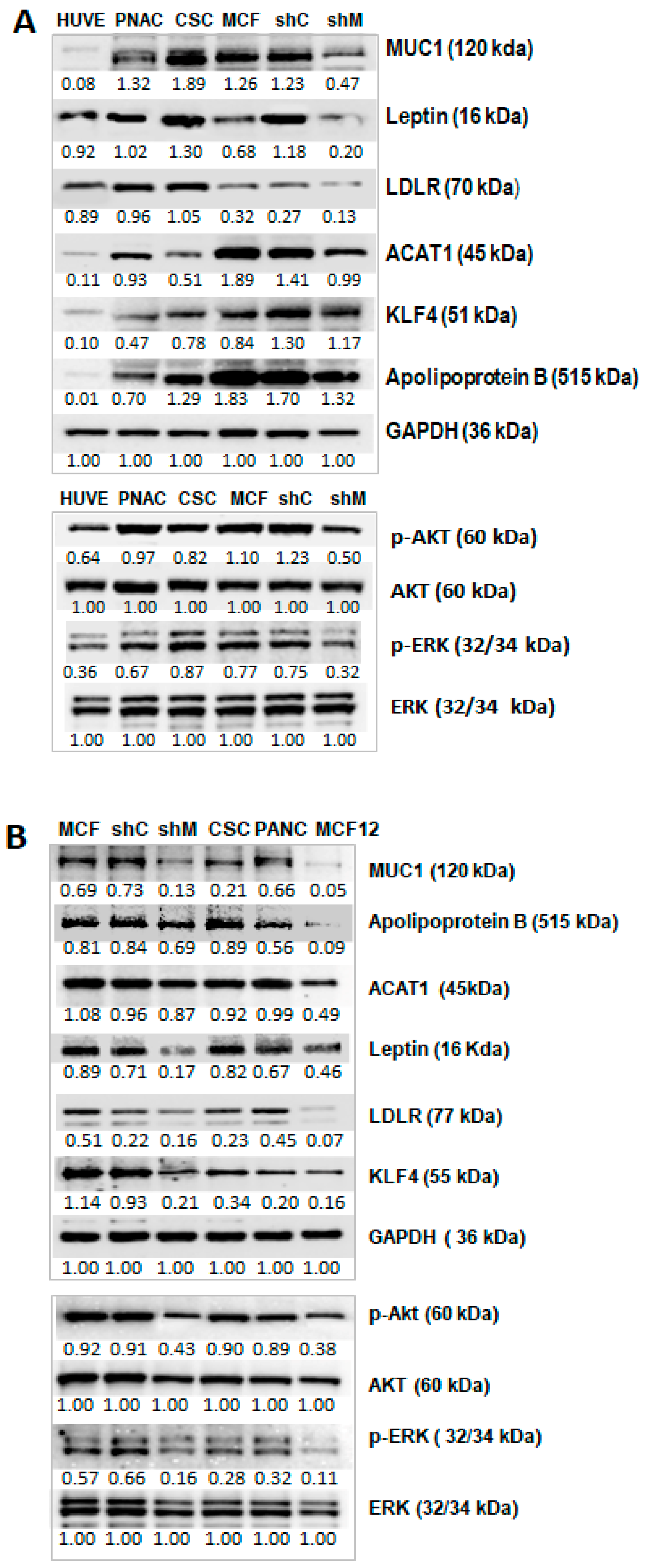

2.1.2. Signalling Pathways and Proteins Implicated in Cholesterol Metabolism Were Also Impacted in TA-MUC1 Cancer Cells

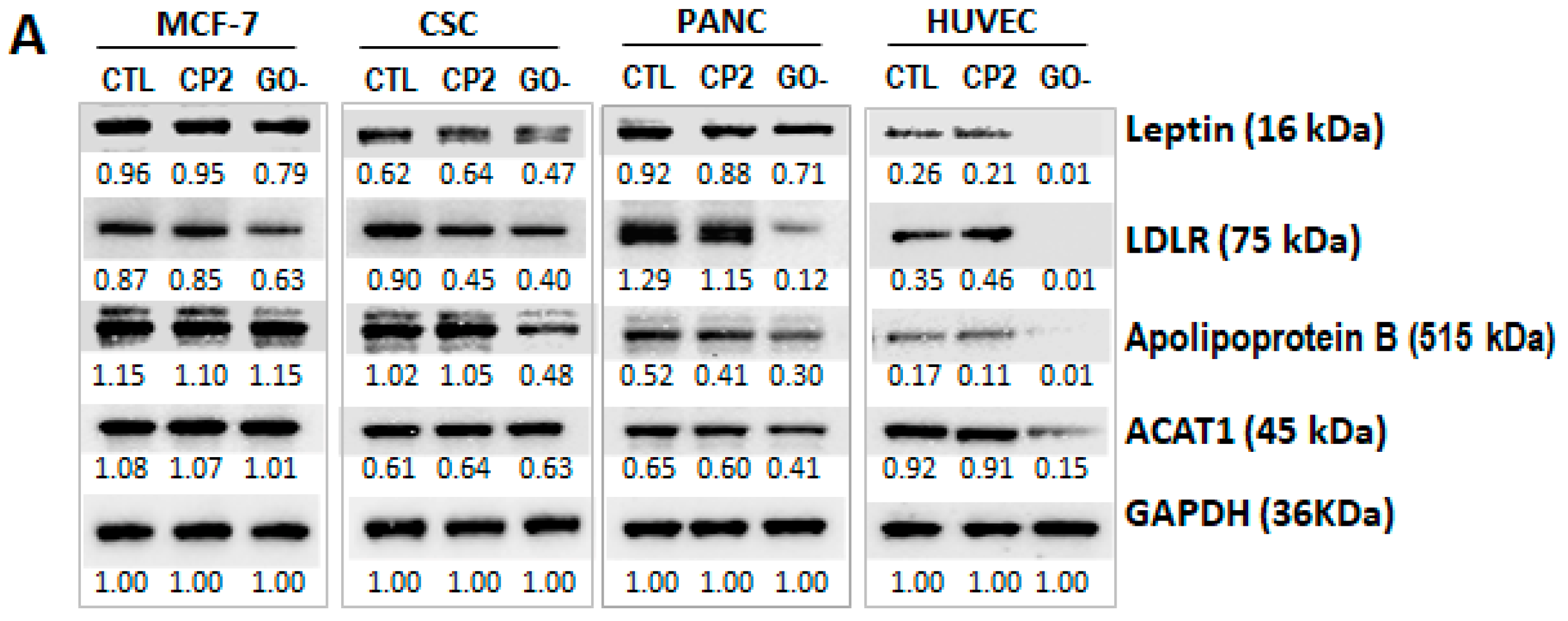

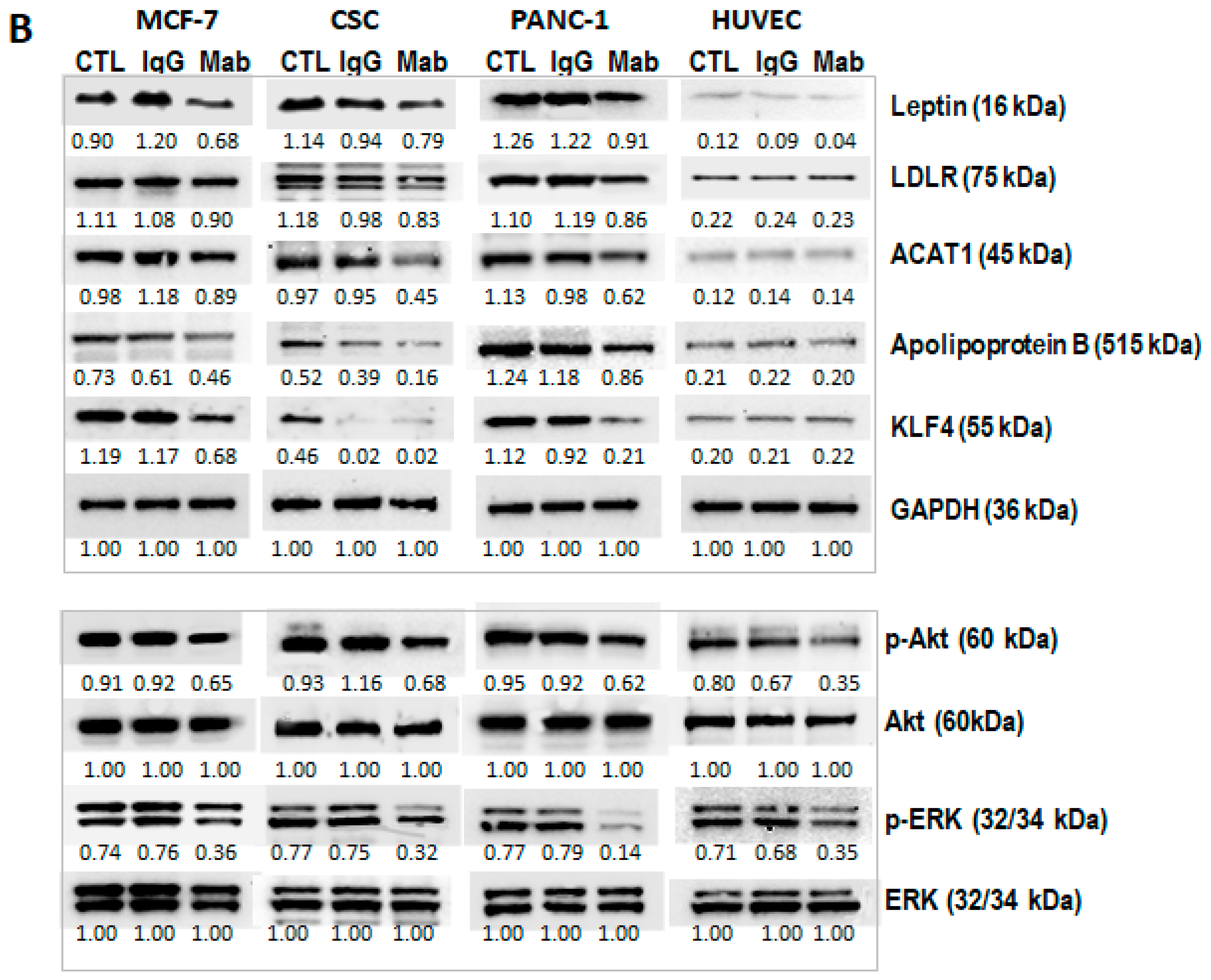

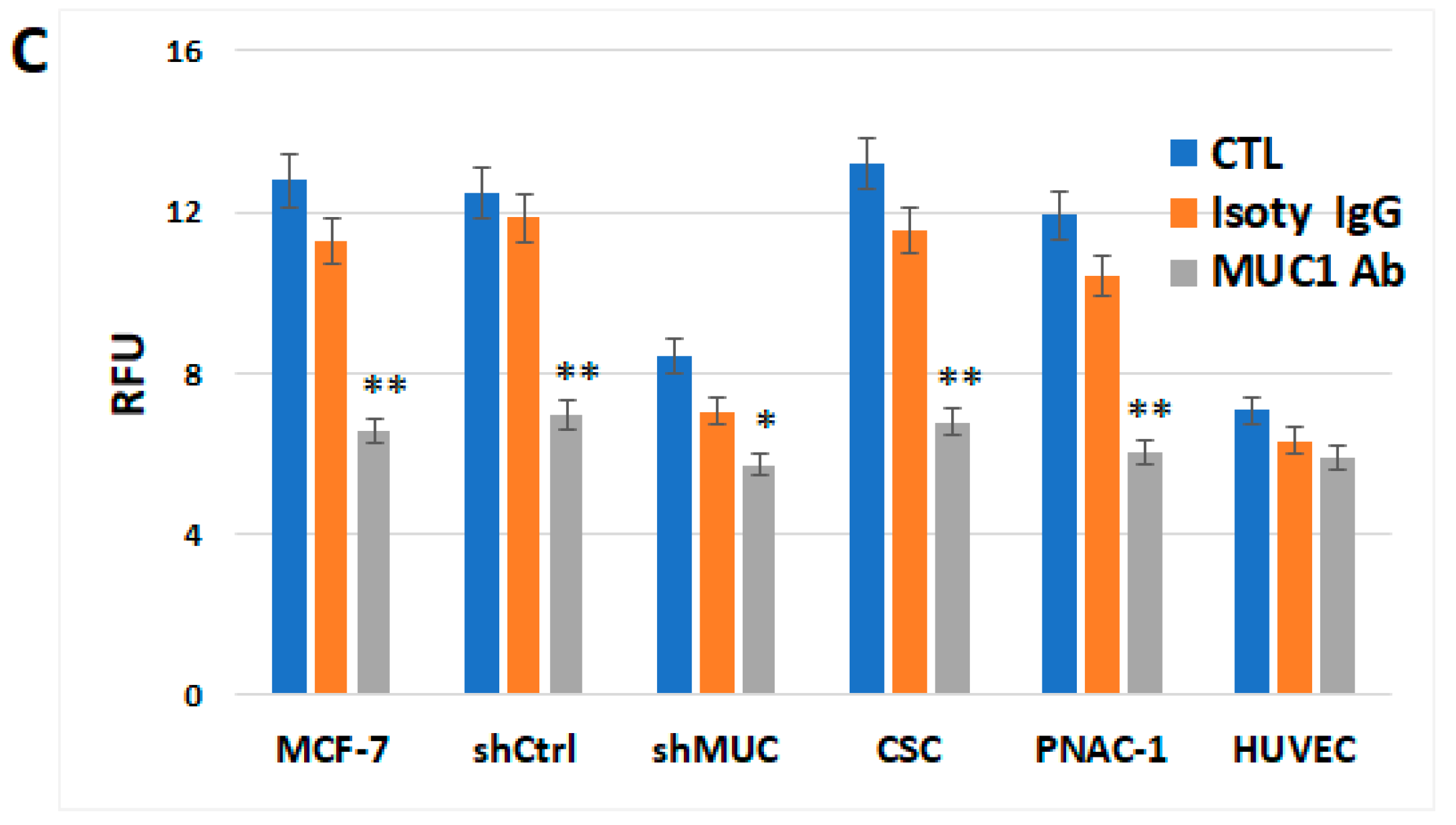

2.1.3. TA-MUC1’s Effect on Cholesterol Metabolism Within Different Cancer Cells Was Further Investigated Using MUC1 Inhibitor GO-203 and Anti-TA-MUC1 Antibody

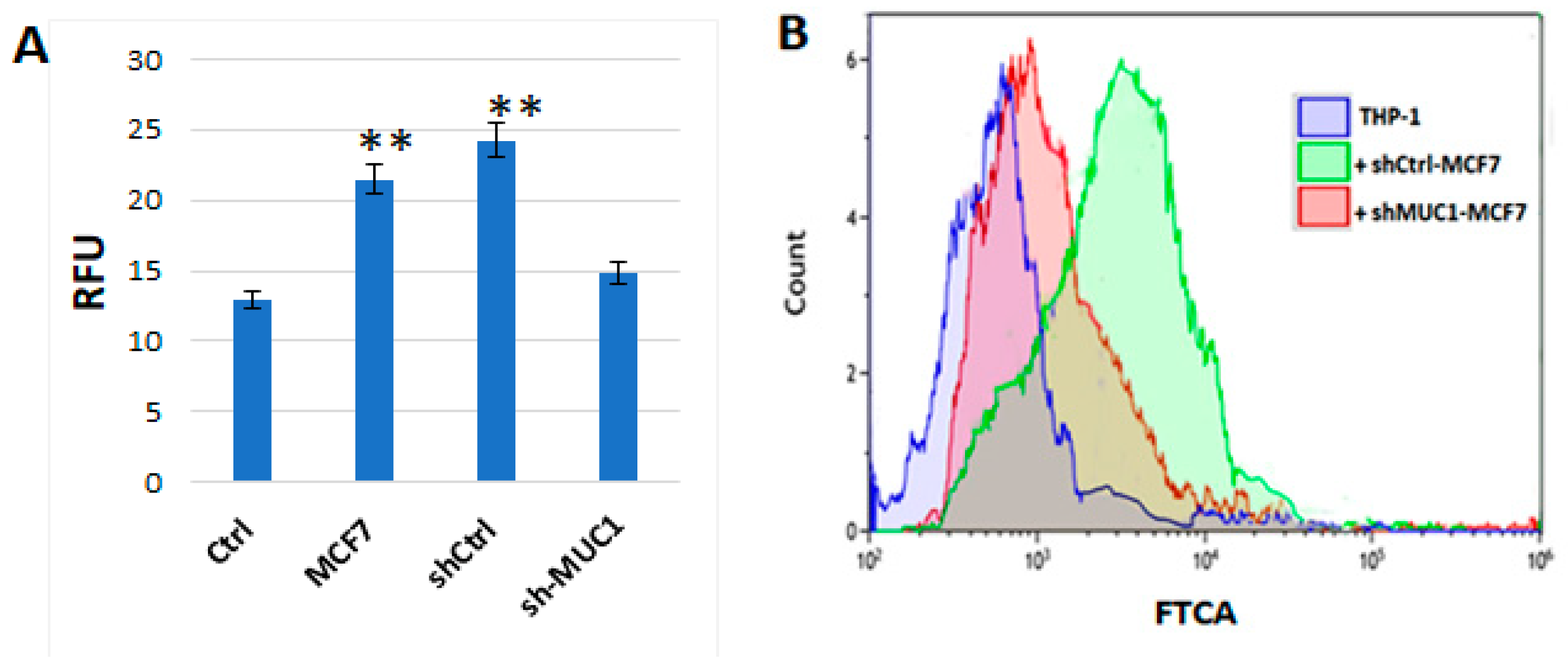

2.2. Cholesterol Metabolism by THP-1 Cells Was Modulated When Cocultured with Breast Cancer MCF-7 Cells

2.2.1. TA-MUC1 Impacted the Cholesterol Uptake of THP1 Cells When Cocultured with Cancer Cells

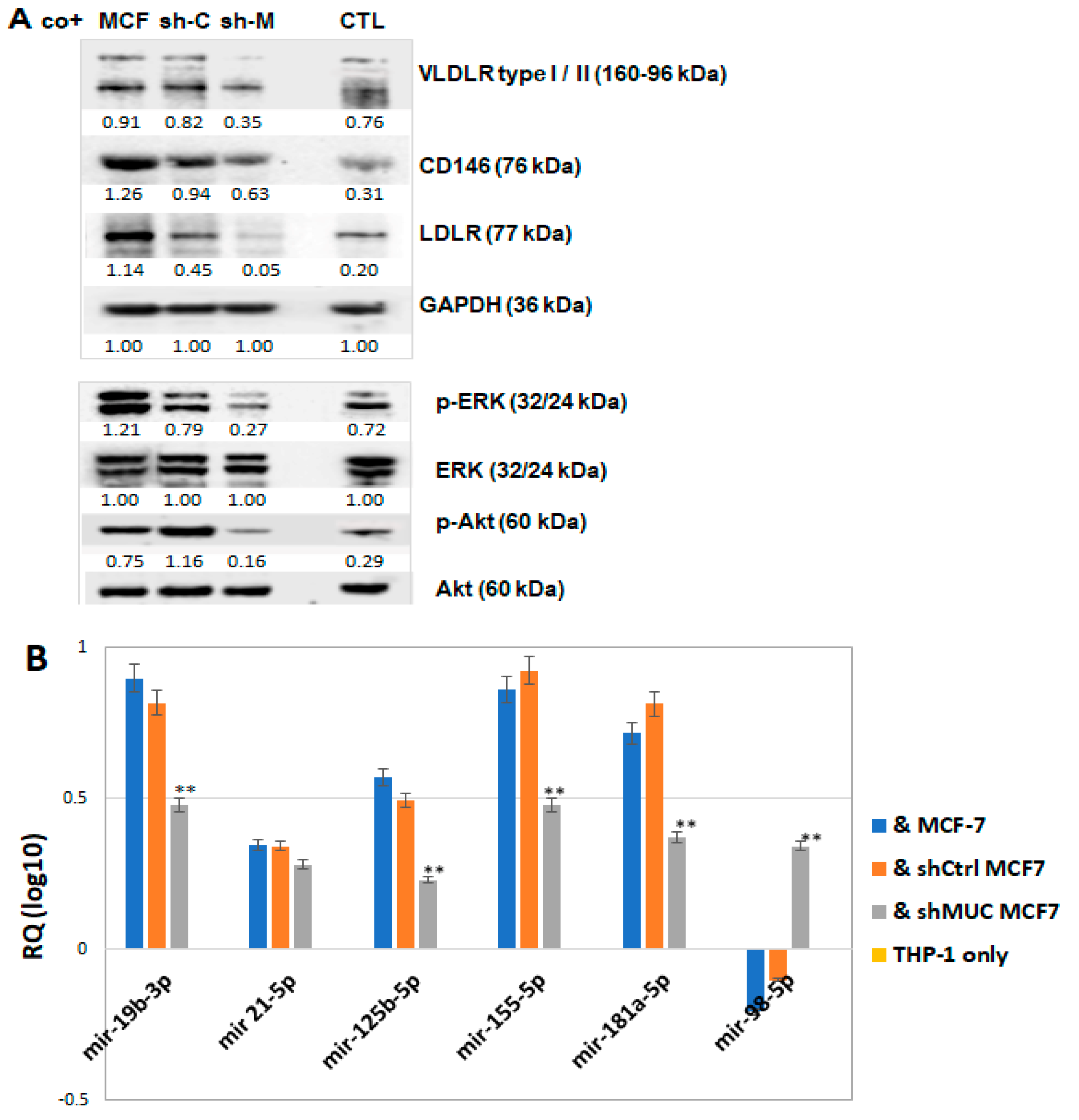

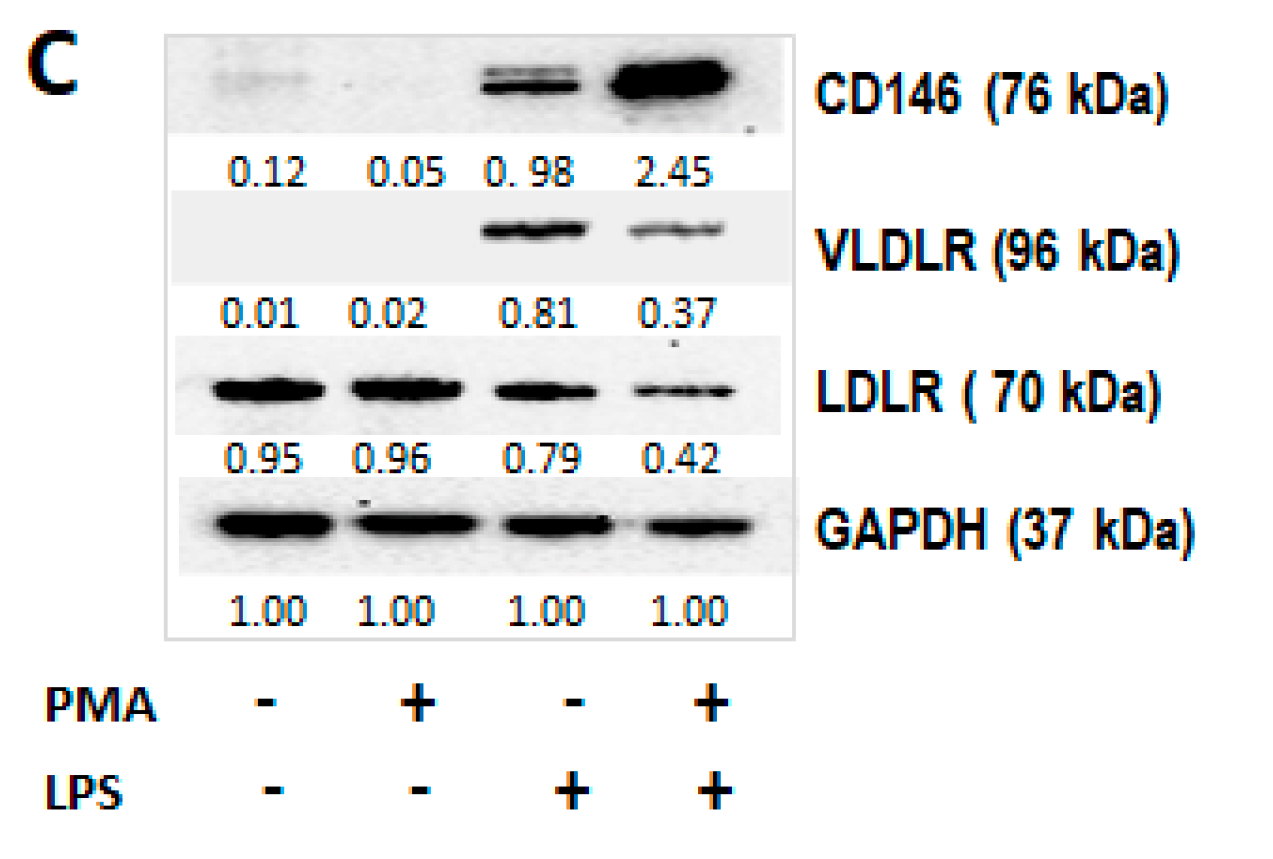

2.2.2. TA-MUC1 Induced Pro-Differentiation Proteins in THP-1 Cells Cocultured with Cancer Cells

2.2.3. TA-MUC1 Modulates miRNAs Relevant to the Regulation of Lipid Retention and Differentiation (Foam Cell Formation) in THP-1 Cells Cocultured with Cancer Cells

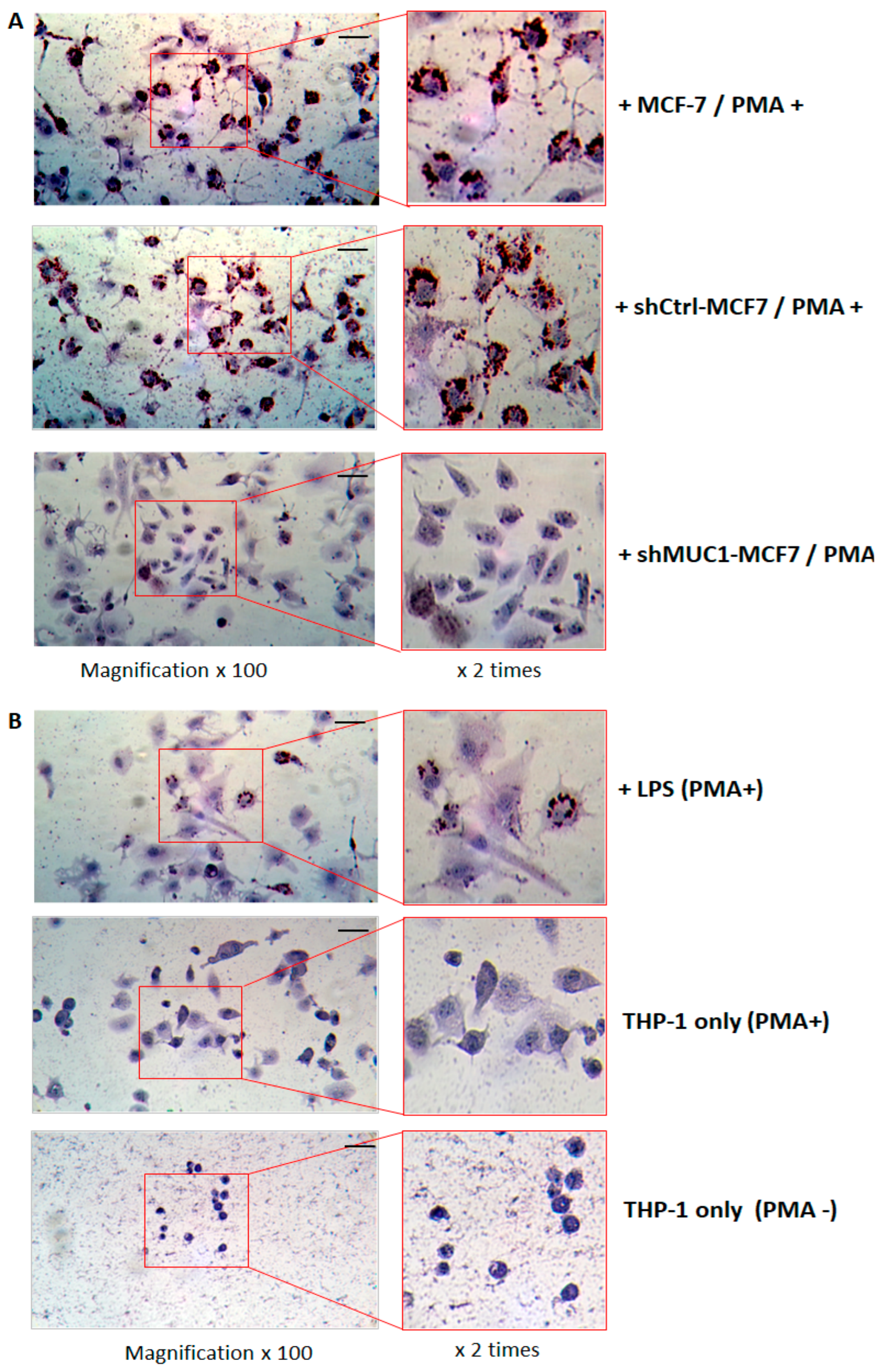

2.2.4. TA-MUC1 Contributes to THP-1 Macrophages Differentiation as Exhibited by Foam Cell Formation When Cocultured with Cancer Cells

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TA-MUC1 | Tumour-associated Mucin |

| LDLR | Low-density lipoprotein receptor |

| VLDLR | Very low-density lipoprotein receptor |

| ABCA1 | ATP-binding cassette sub-family A member 1 |

| ACAT1 | Acetyl-Coenzyme A acetyltransferase 1 |

| KLF4 | Krüppel-like factor 4 |

| Apo B | Apolipoprotein B |

| PANC-1 | Pancreatic cancer cells |

| CSC | Enriched breast cancer stem cells |

| sEVs | Small extracellular vesicles |

| LPS | Lipopolysacharide |

| TF | Tissue factor |

| TAMS | Tumour-associated macrophages |

| PAR | Protease-activated receptors |

References

- Tapia-Vieyra, J.V.; Delgado-Coello, B.; Mas-Oliva, J. Therosclerosis and Cancer; A Resemblance with Far-reaching Implications. Arch. Med. Res. 2017, 48, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubín, S.R.; Cordero, A. The Two-way Relationship Between Cancer and Atherosclerosis. Rev. Española Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2019, 72, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, L.; Zhang, W.; Sun, D. The Relationship Between Cancer and Functional and Structural Markers of Subclinical Atherosclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 849538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polomski, E.A.; Heemelaar, J.C.; de Ronde, M.E.; Al Jaff, A.A.; Mertens, B.J.A.; van Dijkman, P.R.; Jukema, J.W.; Antoni, M.L. Increased prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis in cancer survivors: A matched cross-sectional study with coronary CT angiography. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, ehae666.3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Scully, M. Tumour-associated Mucin1 correlates with the procoagulant properties of cancer cells of epithelial origin. Thromb. Update 2022, 9, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Scully, M. Downregulation of Mucin1 in Cancer Cells is Associated with Modulation of Calcium signalling Pathways and Alteration in Procoagulant Related Activity. Med. Res. Arch. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Ballester, M.; Herrero-Cervera, A.; Vinué, Á.; Martínez-Hervás, S.; González-Navarro, H. Impact of Cholesterol Metabolism in Immune Cell Function and Atherosclerosis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsi, V.; Papakonstantinou, I.; Tsioufis, K. Atherosclerosis, Diabetes Mellitus, and Cancer: Common. Epidemiology, Shared Mechanisms, and Future Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayengbam, S.S.; Singh, A.; Pillai, A.D.; Bhat, M.K. Influence of cholesterol on cancer progression and therapy. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Xi, M.; Xia, B.; Deng, K.; Yang, J. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in tumor microenvironment: From mechanisms to therapeutics. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Pei, J.; Li, R.; Yang, Y. Targeting lipid metabolism: Novel insights and therapeutic advances in pancreatic cancer treatment. Lipids Health Dis. 2025, 24, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehla, K.; Singh, P.K. MUC1: A Novel Metabolic Master Regulator. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1845, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitroda, S.P.; Khodarev, N.N.; Beckett, M.A.; Kufe, D.W.; Weichselbaum, R.R. MUC1-induced alterations in a lipid metabolic gene network predict response of human breast cancers to tamoxifen treatment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5837–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.H.; Afdhal, N.H.; Gendler, S.J.; Wang, D.Q.H. Lack of the intestinal Muc1 mucin impairs cholesterol uptake and absorption but not fatty acid uptake in Muc1−/− mice. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2004, 287, G547–G554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, V.; Gennaro, M.L. Foam Cells: One Size Doesn’t Fit All. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 1163–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, Y.; Zheng, H.; Cao, R.Y. Foam Cells in Atherosclerosis: Novel insights into its origins, consequences, and molecular mechanisms. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 845942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ijaz, A.; Yarlagadda, B.; Orecchioni, M. Foamy macrophages in atherosclerosis: Unraveling the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory roles in disease progression. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1589629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, E.; Pearce, S.; Xiao, Q. Foam cell formation: A new target for fighting atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2019, 112, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galindo, C.L.; Khan, S.; Zhang, X.; Yeh, Y.; Liu, Z.; Razan, B. Lipid-laden foam cells in the pathology of atherosclerosis: Shedding light on new therapeutic targets. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2023, 27, 1231–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanasaki, K.; Yamada, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Ishimoto, Y.; Saiga, A.; Ono, T.; Ikeda, M.; Notoya, M.; Kamitani, S.; Arita, H. Potent modification of low-density lipoprotein by group X secretory phospholipase A2 is linked to macrophage foam cell formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 29116–29124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R. Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease. Am. Heart J. 1999, 138, S419–S420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navab, M.; Berliner, J.A.; Watson, A.D.; Hama, S.Y.; Territo, M.C.; Lusis, A.J.; Shih, D.M.; Van Lenten, B.J.; Frank, J.S.; Demer, L.L.; et al. The Yin and Yang of oxidation in the development of the fatty streak. A review based on the 1994. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1996, 16, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuangbubpha, P.; Thara, S.; Sriboonaied, P.; Saetan, P.; Tumnoi, W.; Charoenpanich, A. Optimizing THP-1 Macrophage Culture for an Immune-Responsive Human Intestinal Model. Cells 2023, 12, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazan, A.; Marusiak, A.A. Protocols for Co-Culture Phenotypic Assays with Breast Cancer Cells and THP-1-Derived Macrophages. J. Mammary Gland. Biol. Neoplasia 2024, 29, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vis, M.A.M.; Ito, K.; Hofmann, S. Impact of Culture Medium on Cellular Interactions in in vitro Co-culture Systems. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Zou, T.; Shen, X.; Nelson, P.J.; Li, J.; Wu, C.; Yang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Bruns, C.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Lipid metabolism in cancer progression and therapeutic strategies. Med. Comm. 2020, 2, 27–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kufe, D.W. MUC1-C oncoprotein as a target in breast cancer: Activation of signaling pathways and therapeutic approaches. Oncogene 2013, 32, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, M.; Sinha, R.K.; Kumar, M.; Alam, M.; Yin, L.; Raina, D.; Kharbanda, A.; Panchamoorthy, G.; Gupta, D.; Singh, H.; et al. Intracellular Targeting of the Oncogenic MUC1-C Protein with a Novel GO-203 Nanoparticle Formulation. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 2338–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Alam, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Uchida, Y.; Al-Obaid, O.; Kharbanda, S.; Kufe, D. Targeting MUC1-C inhibits the AKT-S6K1-elF4A pathway regulating TIGAR translation in colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heublein, S.; Page, S.; Mayr, D.; Schmoeckel, E.; Trillsch, F.; Marmé, F.; Mahner, S.; Jeschke, U.; Vattai, A. Potential interplay of the Gatipotuzumab epitope TA-MUC1 and estrogen receptors in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawa-Wejksza, K.; Dudek, A.; Lemieszek, M.; Kaławaj, K.; Kandefer-Szerszeń, M. Colon cancer-derived conditioned medium induces differentiation of THP-1 monocytes into a mixed population of M1/M2 cells. Tumor Biol. 2018, 40, 1010428318797880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banka, C.L.; Black, A.S.; Dyer, C.A.; Curtiss, L.K. THP-1 cells form foam cells in response to coculture with lipoproteins but not platelets. J. Lipid Res. 1991, 32, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Duan, H.; Qian, Y.; Feng, L.; Wu, Z.; Wang, F.; Feng, J.; Yang, D.; Qin, Z.; Yan, X. Macrophagic CD146 promotes foam cell formation and retention during atherosclerosis. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 352–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herijgers, N.; Van Eck, M.; Groot, P.H.; Hoogerbrugge, P.M.; Van Berkel, T.J. Low density lipoprotein receptor of macrophages facilitates atherosclerotic lesion formation in C57Bl/6 mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2000, 20, 1961–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosaka, S.; Takahashi, S.; Masamura, K.; Kanehara, H.; Sakai, J.; Tohda, G.; Okada, E.; Oida, K.; Iwasaki, T.; Hattori, H.; et al. Evidence of macrophage foam cell formation by very low-density lipoprotein receptor: Interferon-gamma inhibition of very low-density lipoprotein receptor expression and foam cell formation in macrophages. Circulation 2001, 27, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, Q.; Liu, D.; Li, X.; Guo, M.; Chen, X.; Liao, J.; Lei, R.; Li, W.; Huang, H.; et al. CD146 promotes malignant progression of breast phyllodes tumor through suppressing DCBLD2 degradation and activating the AKT pathway. Cancer Commun. 2023, 43, 1244–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Sinha, A.; Saikia, S.; Gogoi, B.; Rathore, A.K.; Das, A.S.; Pal, D.; Buragohain, A.K.; Dasgupta, S. Inflammation-induced mTORC2-Akt-mTORC1 signaling promotes macrophage foam cell formation. Biochimie 2018, 151, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightbody, R.J.; Taylor, J.M.W.; Dempsie, Y.; Graham, A. MicroRNA sequences modulating inflammation and lipid accumulation in macrophage “foam” cells: Implications for atherosclerosis. World J. Cardiol. 2020, 12, 303–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbich, C.; Kuehbacher, A.; Dimmeler, S. Role of microRNAs in vascular diseases, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2008, 79, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerneur, C.; Cano, C.E.; Olive, D. Major pathways involved in macrophage polarization in cancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1026954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, S.; Mukherjee, P. MUC1: A multifaceted oncoprotein with a key role in cancer progression. Trends Mol. Med. 2014, 20, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olie, R.H.; van der Meijden, P.E.J.; Cate, H. The coagulation system in atherothrombosis: Implications for new therapeutic strategies. Res. Pract. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 2, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.N.; Hernández-Cáceres, M.P.; Asencio, C.; Torres, B.; Solis, B.; Owen, G.I. Deciphering the Role of the Coagulation Cascade and Autophagy in Cancer-Related Thrombosis and Metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 605314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuberger, D.M.; Schuepbach, R.A. Protease-activated receptors (PARs): Mechanisms of action and potential therapeutic modulators in PAR-driven inflammatory diseases. Thromb. J. 2019, 17, 4, Correction in Thromb. J. 2019, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalampogias, A.; Siasos, G.; Oikonomou, E.; Tsalamandris, S.; Mourouzis, K.; Tsigkou, V.; Vavuranakis, M.; Zografos, T.; Deftereos, S.; Stefanadis, C.; et al. Mechanisms in Atherosclerosis: The Role of Calcium. Med. Chem. 2016, 12, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neels, J.G.; Leftheriotis, G.; Chinetti, G. Atherosclerosis Calcification: Focus on Lipoproteins. Metabolites 2023, 13, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Ortiz, A.; Badimon, J.J.; Falk, E.; Fuster, V.; Meyer, B.; Mailhac, A.; Weng, D.; Shah, P.K.; Badimon, L. Characterization of the relative thrombogenicity of atherosclerotic plaque components: Implications for consequences of plaque rupture. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1994, 23, 1562–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee-Rueckert, M.; Lappalainen, J.; Kovanen, P.T.; Escola-Gil, J.C. Lipid-Laden Macrophages and Inflammation in Atherosclerosis and Cancer: An Integrative View. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 777822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marelli, G.; Morina, N.; Portale, F.; Pandini, M.; Iovino, M.; Conza, G.D.; Ho, P.C.; Mitri, D.D. Lipid-loaded macrophages as new therapeutic target in cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e004584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poznyak, A.V.; Nikiforov, N.G.; Starodubova, A.V.; Popkova, T.V.; Orekhov, A.N. Macrophages and foam cells: Brief overview of their role, linkage, and targeting potential in atherosclerosis. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.C.H.; Bennett, M.R. Vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, J.B.; Kromann, E.B. Pitfalls and opportunities in quantitative fluorescence-based nanomedicine studies—A commentary. J. Control. Release 2021, 335, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxfield, F.R.; Wüstner, D. Analysis of cholesterol trafficking with fluorescent probes. Methods Cell Biol. 2012, 108, 367–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, J.B. Pitfalls associated with lipophilic fluorophore staining of extracellular vesicles for uptake studies. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1582237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Luo, X.; Lin, Z.; Tian, Y.; Ajit, S.K. Uptake of Fluorescent Labeled Small Extracellular Vesicles In Vitro and in Spinal Cord. J. Vis. Exp. 2021, 171, 10–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Scully, M.; Dawson, G.; Goodwin, C.; Xia, M.; Lu, X.; Kakkar, A. Perturbation of the heparin/heparin-sulfate interactome of human breast cancer cells modulates pro-tumourigenic effects associated with PI3K/Akt and MAPK/ERK signalling. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 109, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Papadimitriou, J.; Burchell, J.M.; Graham, R.; Beatson, R. Latest developments in MUC1 immunotherapy. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chu, Y.; Li, S.; Yu, L.; Deng, H.; Liao, C.; Liao, X.; Yang, C.; Qi, M.; Cheng, J.; et al. The oncoprotein MUC1 facilitates breast cancer progression by promoting Pink1-dependent mitophagy via ATAD3A destabilization. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Scully, M. Tumour-Associated MUC1 Exerts Multiple Effects on Cholesterol and Lipid Metabolism—A Potential Pathogenic Effector of Atherosclerosis in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010518

Chen Y, Scully M. Tumour-Associated MUC1 Exerts Multiple Effects on Cholesterol and Lipid Metabolism—A Potential Pathogenic Effector of Atherosclerosis in Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):518. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010518

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yunliang, and Michael Scully. 2026. "Tumour-Associated MUC1 Exerts Multiple Effects on Cholesterol and Lipid Metabolism—A Potential Pathogenic Effector of Atherosclerosis in Cancer" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010518

APA StyleChen, Y., & Scully, M. (2026). Tumour-Associated MUC1 Exerts Multiple Effects on Cholesterol and Lipid Metabolism—A Potential Pathogenic Effector of Atherosclerosis in Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010518