1. Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a hepatotropic virus that remains a leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide [

1]. Chronic HCV infection (CHC) continues to account for a substantial global health burden, including approximately 242,000 deaths and 1.5 million new infections annually [

2]. CHC develops in around 75% of people who acquire HCV. Viral persistence can induce hepatic steatosis, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [

3]. Moreover, spontaneous clearance (SC) in the acute phase (<6 months) occurs in a variable percentage of patients (20–40%) [

4]. Factors affecting SC are host, immune, viral, environmental, and genetic factors [

5]. Patients who spontaneously cleared the infection may still progress in liver injury, highlighting the role of host and genetic factors in modulating hepatic outcomes [

6].

Obesity is a significant risk factor for the development of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). However, individual susceptibility to MASLD varies considerably by ethnicity [

7]. MASLD has rapidly become the most common cause of liver disease worldwide, currently affecting 38% of the global population. Although MASLD does not always progress to advanced liver disease, it has become the leading cause of liver transplantation [

8]. Several factors, including environmental, metabolic, immune, genetic, and epigenetic factors, can affect the progression of MASLD to severe forms of the disease [

9].

Genetic factors play a crucial role in the onset and progression of steatotic liver disease (SLD). The Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (

PNPLA3) gene, which encodes a triglyceride hydrolase, is among the most strongly associated genes with liver damage and SLD worldwide [

10,

11]. The genetic influence of

PNPLA3 on the risk of MASLD-related liver injury becomes progressively stronger with increasing body mass index (BMI) [

12]. Evidence from Hispanic pediatric populations shows that

PNPLA3 variants are associated with increased hepatic fat accumulation and metabolic alterations, underscoring the BMI-dependent nature of this genetic risk [

13]. Due to genetic predisposition and high prevalence of overweight and obesity in the Mexican population [

14], it is crucial to explore the effect of

PNPLA3 polymorphisms on liver damage. Among HCV patients, the

PNPLA3 gene has been shown to contribute to HCC development, elevated alanine aminotransferase levels, and faster progression of cirrhosis among patients infected with genotype 1b [

15]. However, the contribution of

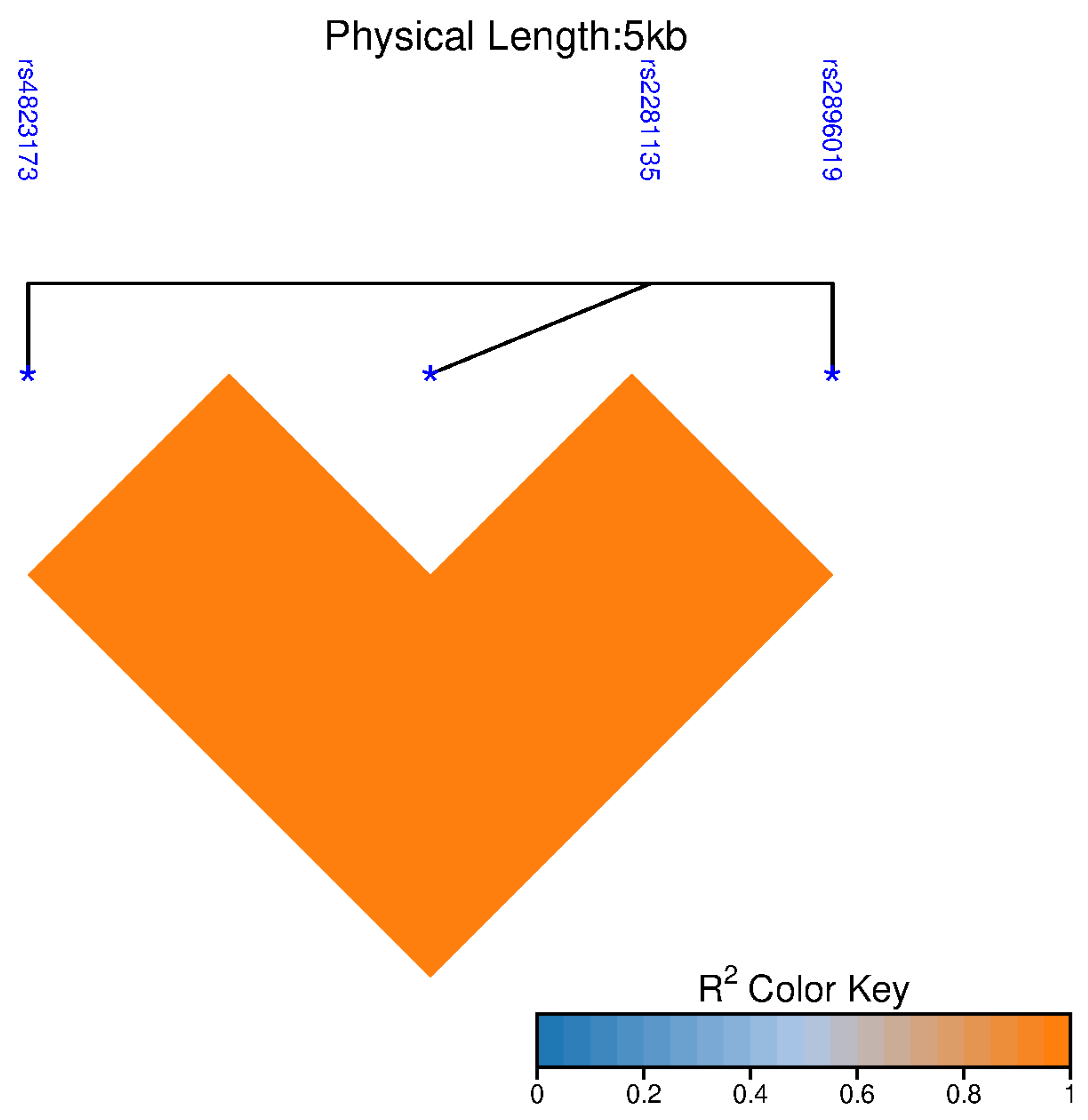

PNPLA3 variations in HCV infection remains largely unknown. A Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) of Mexican Americans identified three single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the

PNPLA3 gene that were associated with elevated liver enzyme levels in a cohort of subjects with various metabolic and cardiometabolic diseases [

16]. These SNPs are intronic variants, and their protein effects remain unknown. This study aimed to assess the contribution of the

PNPLA3 polymorphisms rs4823173 (G>A), rs2896019 (T>G), and rs2281135 (G>A) to liver damage in patients with HCV infection.

3. Discussion

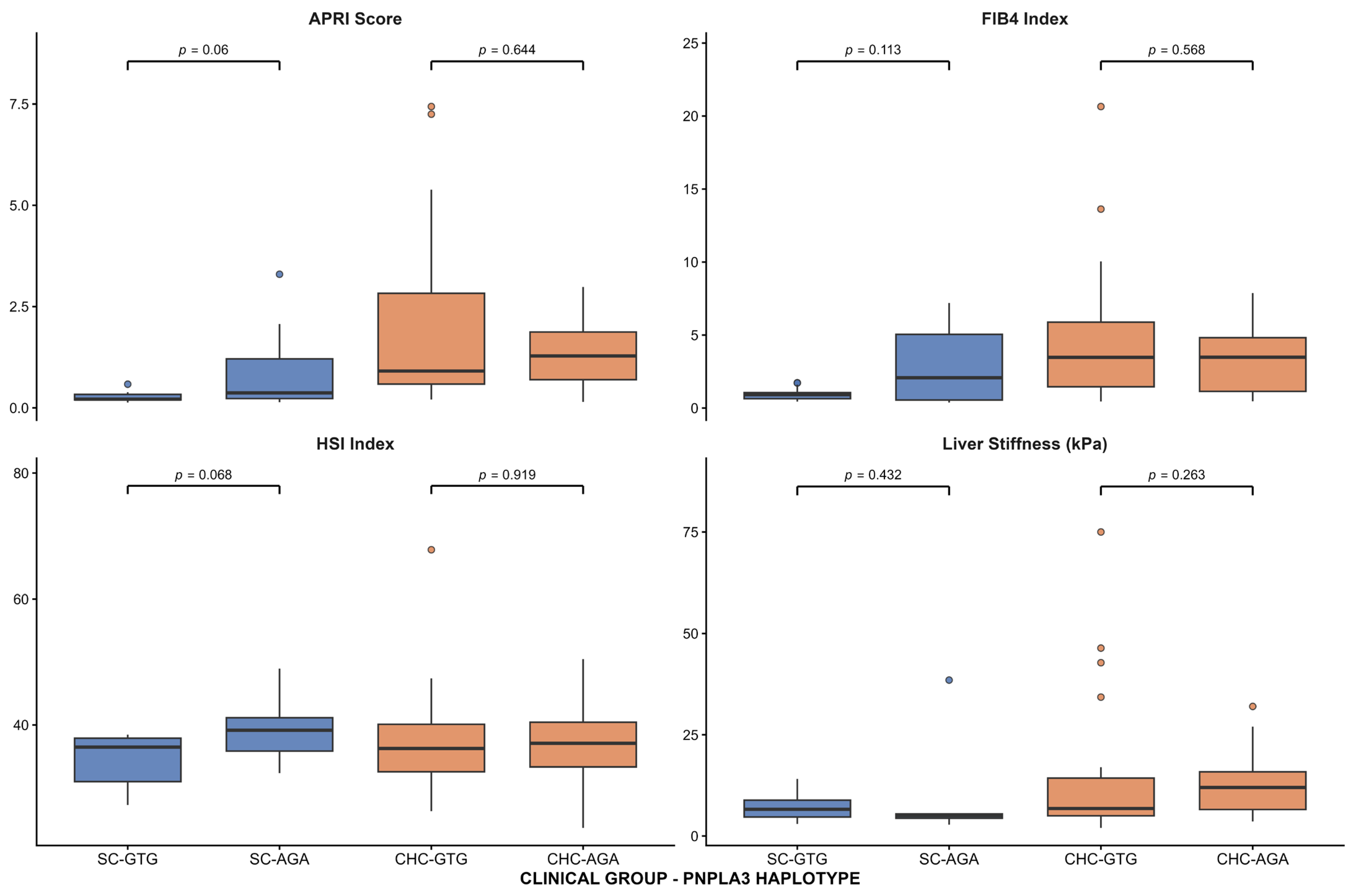

In this study, we evaluated the effects of three intronic polymorphisms in the PNPLA3 gene on liver damage, as assessed by serum markers, noninvasive scores, and transient elastography, in patients with HCV infection. We found an association between the three SNPs and elevated AST, ALT, and APRI levels, as well as reduced platelet counts, in patients who have cleared the infection, but not in those with CHC. These associations were also observed at the haplotype level. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report describing this association in individuals with a history of HCV infection who achieved spontaneous viral clearance.

Over the past 15 years,

PNPLA3 has emerged as one of the most influential genetic determinants of liver disease [

17]. To date, studies of

PNPLA3 gene polymorphisms have primarily focused on the rs738409 (I148M) variant and its association with MASLD [

18]. Nonetheless, GWAS studies across populations have identified mutations in

PNPLA3 as contributing to steatotic liver disease and liver damage beyond the rs738409 variant [

16,

19,

20]. In this context, increasing attention has been given to intronic variation within the

PNPLA3 locus as a potential contributor to interindividual and population-specific differences in liver disease susceptibility. Although these variants do not alter the protein-coding sequence, several studies have reported associations between intronic

PNPLA3 polymorphisms and liver-related phenotypes, suggesting that they may capture relevant regulatory or haplotypic effects influencing disease expression [

21]. The evaluation of multiple intronic markers within the locus may therefore provide complementary information to coding variants, particularly in populations with complex genetic backgrounds, and help explain variability in liver injury severity that is not fully accounted for by rs738409 alone [

22]. It was recently reported that intronic polymorphisms in

PNPLA3 (rs4823173, rs2896019, and rs2281135) are associated with elevated liver aminotransferases among Mexican American subjects with different metabolic and cardiometabolic diseases, as well as in Mexican patients with MASLD [

16,

23]. However, the effect of these variants on liver damage in Mexican patients with HCV infection remains unknown.

The Mexican population has a tripartite genetic background (Amerindian, Caucasian, and African), remarkably implicated with increased risk of diverse health issues, including liver diseases [

24,

25]. Recent lifestyle changes, particularly the westernization of diet, have been identified as a major contributor to this current risk pattern among the mestizo population [

25]. Currently, approximately 75% of Mexicans are overweight or obese, and a high prevalence of MASH has been reported among young individuals with obesity [

14,

26]. Given this genetic and metabolic context, it is relevant to explore how specific genetic variants contribute to liver injury in this population.

In this study, the three SNPs in the

PNPLA3 gene—AA-rs4823173, GG-rs2896019, and AA-rs2281135—and their risk haplotype (AGA) were associated with elevated ALT and AST levels in patients who cleared HCV infection, but not in CHC patients, supporting a haplotype-dependent effect of

PNPLA3 variation in patients who cleared HCV infection. Information on the stage of liver fibrosis is crucial for managing patients with hepatitis C, as it provides prognostic information and assists in therapeutic decisions [

27]. Although liver biopsy represents the gold standard for evaluating the stage of liver fibrosis, it remains an invasive procedure with inherent risks [

28]. However, over the past decade, imaging techniques and serum marker tests have become key methods for assessing liver injury, often obviating the need for liver biopsy and histological analysis [

29]. It is accepted that blood levels of ALT and AST are a consequence of liver cell membrane damage, but also reflect relevant aspects of liver physiology and pathophysiology beyond hepatocyte membrane disruption [

30]. ALT and AST are usually elevated in chronic HCV infection in parallel with the severity of liver disease, which returns to the normal range after viral eradication [

31,

32]. Although in the group of SC patients, the means of ALT and AST were under the normal range, patients carrying the risk genotypes reached the highest levels of AST (>42 IU/L) and ALT (>37.2 IU/L) comparing with non-carries, indicating that patients with SC may be under the influence of other liver damage triggers or the aftermath of hepatitis C infection. Studies have shown that HCV infection results in persistent epigenetic and transcriptional changes associated with fibrosis and HCC, suggesting that viral cure only partially eliminates the virus-induced pro-fibrogenic and carcinogenic effects [

33,

34]. These results highlight the need for clinical follow-up of patients with SC or sustained virological response to monitor liver damage risk. Moreover, the loss of association in the CHC group may be explained by the predominant influence of chronic inflammation, fibrosis progression, and viral and host factors that affect aminotransferase levels, which could overshadow the effect of the genetic variation [

6]. These results are in line with studies conducted on Japanese and Pakistani chronic HCV-infected patients, where no correlation was found between the rs738409 variant and liver fibrosis [

35,

36]. The divergence between both groups suggests that

PNPLA3-related metabolic and inflammatory pathways may exert a greater effect under conditions of limited viral injury or after viral clearance. Additional studies using human-centric models or humanized mouse models will be required to identify the mechanisms underlying this process [

37].

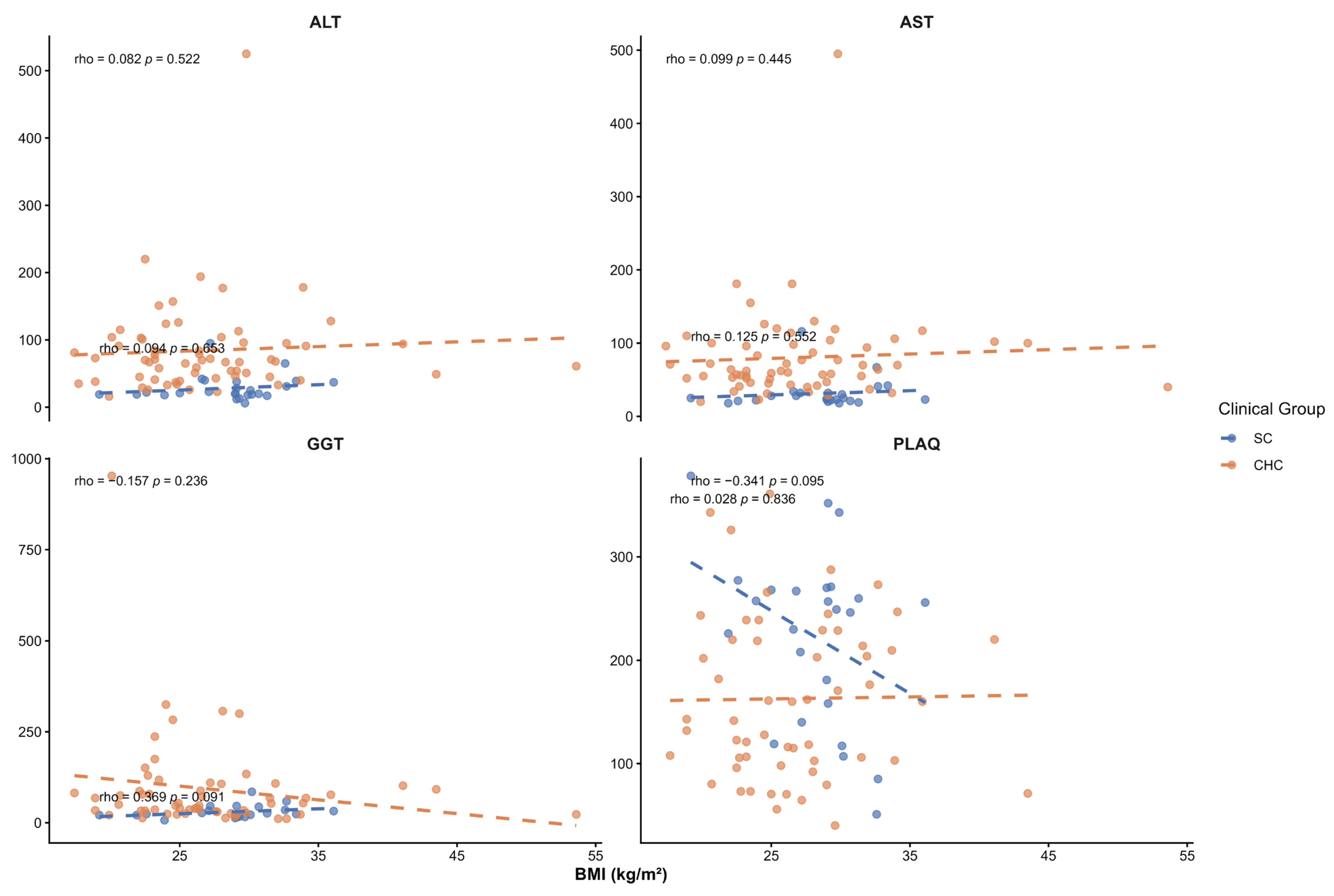

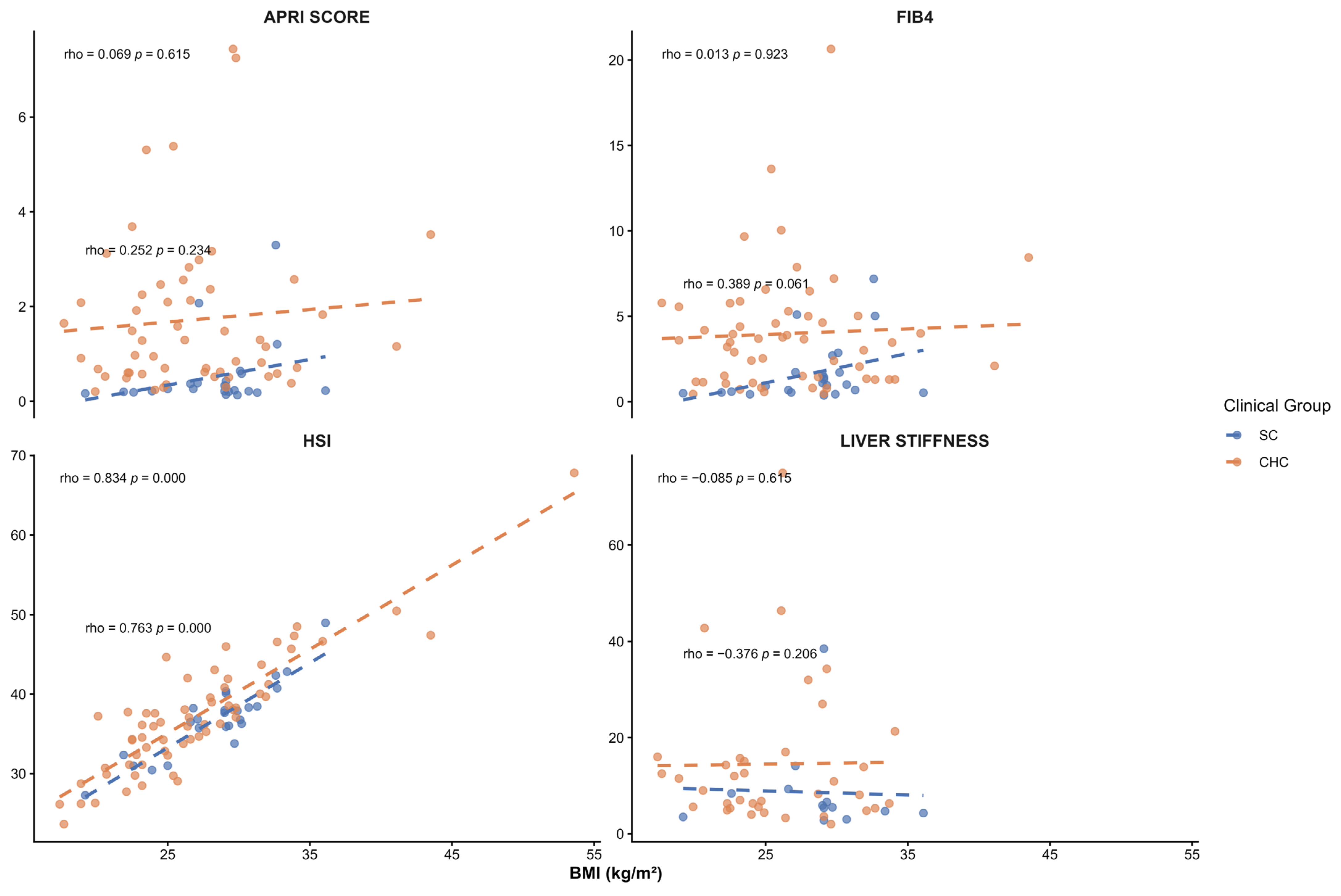

Although liver fat content and its association with

PNPLA3 genotypes were not assessed in this study, the SC group’s mean BMI was in the overweight range. To evaluate whether BMI could confound the observed associations, Spearman correlation analyses were performed between BMI and liver injury markers and noninvasive indices. No significant correlations were observed between BMI and serum liver enzymes (ALT, AST, GGT), platelet count, APRI, FBI-4, or liver stiffness. A positive correlation with the HSI was observed, as expected, since BMI is an integral component of its calculation. Overall, these findings suggest that the associations observed between

PNPLA3 haplotypes and liver injury markers in SC patients are not driven by BMI. A previous analysis of this group of patients reported a dietary pattern characterized by western-type foods, including pork, red meat, soft drinks, bacon, and fried foods [

38]. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that some patients presented with MASLD due to dietary factors or

PNPLA3 variants. Whether these patients have increased hepatic fat accumulation remains to be determined. Indeed, one of the main limitations of our study is the absence of a formal diagnosis of fatty liver. Observational studies have reported an increased likelihood of coronary and carotid atherosclerosis during HCV infection [

39]. Given the dietary patterns among Mexican SC patients and the effect of

PNPLA3 variants on atherosclerosis development [

40], these patients should be followed to monitor the development of cardiometabolic disease.

Platelets serve as an essential indicator of liver function in patients with chronic liver disease [

41]. Thrombocytopenia results from decreased production of the hormone thrombopoietin (TPO) in the damaged liver and/or increased platelet destruction due to phagocytosis in an enlarged spleen. Additionally, impaired hematopoiesis in the bone marrow due to viral infection may further reduce platelet count [

42]. A decreased peripheral platelet count may indicate a more advanced degree of fibrosis in hepatitis C [

43]. Because platelets play a crucial role in liver regeneration, low platelet count exacerbates hepatocyte injury and promotes the progression of cirrhosis [

44]. In the present study, the three

PNPLA3 risk genotypes, AA-rs4823173, GG-rs2896019, and AA-rs2281135, and the risk haplotype AGA were associated with lower platelet counts among SC patients. This finding is in accord with the described effect of the

PNPLA3 at-risk alleles on platelet count [

45]. The

PNPLA3 rs738409 variant has been identified as a modifier of platelet count by exome-chip meta-analysis [

46]. In MASLD patients, the expression of genes involved in platelet biogenesis was associated with

PNPLA3 GG at rs738409 [

45], supporting the concept that

PNPLA3 variants are associated with platelet count. However, the impact of

PNPLA3 on platelets is still largely unexplored.

In accordance with the association between elevated aminotransferases and low platelet count, the three risk genotypes were also associated with APRI levels. APRI is a noninvasive index based on AST, ALT, and platelet counts that predicts fibrosis and cirrhosis in HCV patients [

47]. Interestingly, no significant associations were observed between

PNPLA3 genotypes or haplotypes and FIB-4, HSI, or liver stiffness. This apparent discrepancy may reflect differences in the biological processes captured by these indices. APRI is primarily driven by aminotransferase levels and platelet count, and is particularly sensitive to early or mild hepatic injury [

48]. In contrast, FIB-4 and liver stiffness are more closely related to advanced fibrosis and structural liver changes [

49,

50], which may be less prevalent in patients with spontaneous HCV clearance. Similarly, HSI incorporates metabolic components such as BMI and diabetes, and therefore may not accurately reflect genetically driven liver injury in this context [

51]. These findings suggest that

PNPLA3 intronic variants may preferentially influence biochemical and hematological markers of liver injury rather than established fibrotic remodeling. Thus, determining

PNPLA3 at-risk genotypes could help predict which patients who reach SC or SVR are at risk of developing liver damage.

Genomic and personalized medicine require consideration of the regional genetic and cultural background [

52]. In this context, integrating genetic information with clinical and biochemical markers could improve the early detection of individuals at risk of MASLD or liver injury, enabling tailored preventive and therapeutic approaches [

53]. Emerging evidence suggests that modulation of PNPLA3-related pathways may enable personalized strategies to prevent progression of liver injury, particularly in genetically susceptible individuals [

54]. The present findings emphasize the importance of incorporating genomic profiling into clinical practice to better account for interindividual variability in liver disease susceptibility and progression.