Necrotic Cells Alter IRE1α-XBP1 Signaling and Induce Transcriptional Changes in Glioblastoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

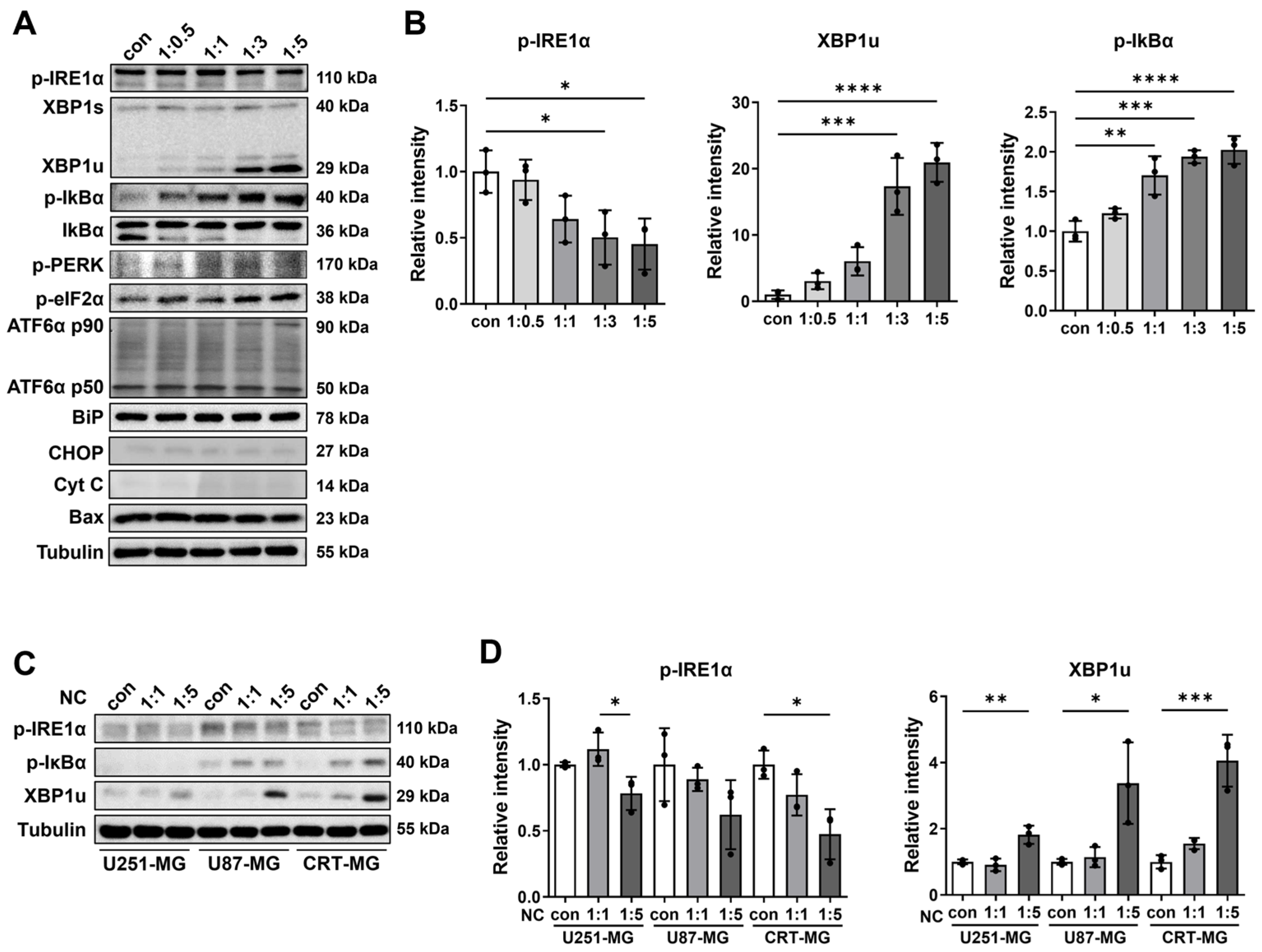

2.1. The Effect of Necrotic Cells on ER Stress and NF-κB Pathways in Glioblastoma Cells

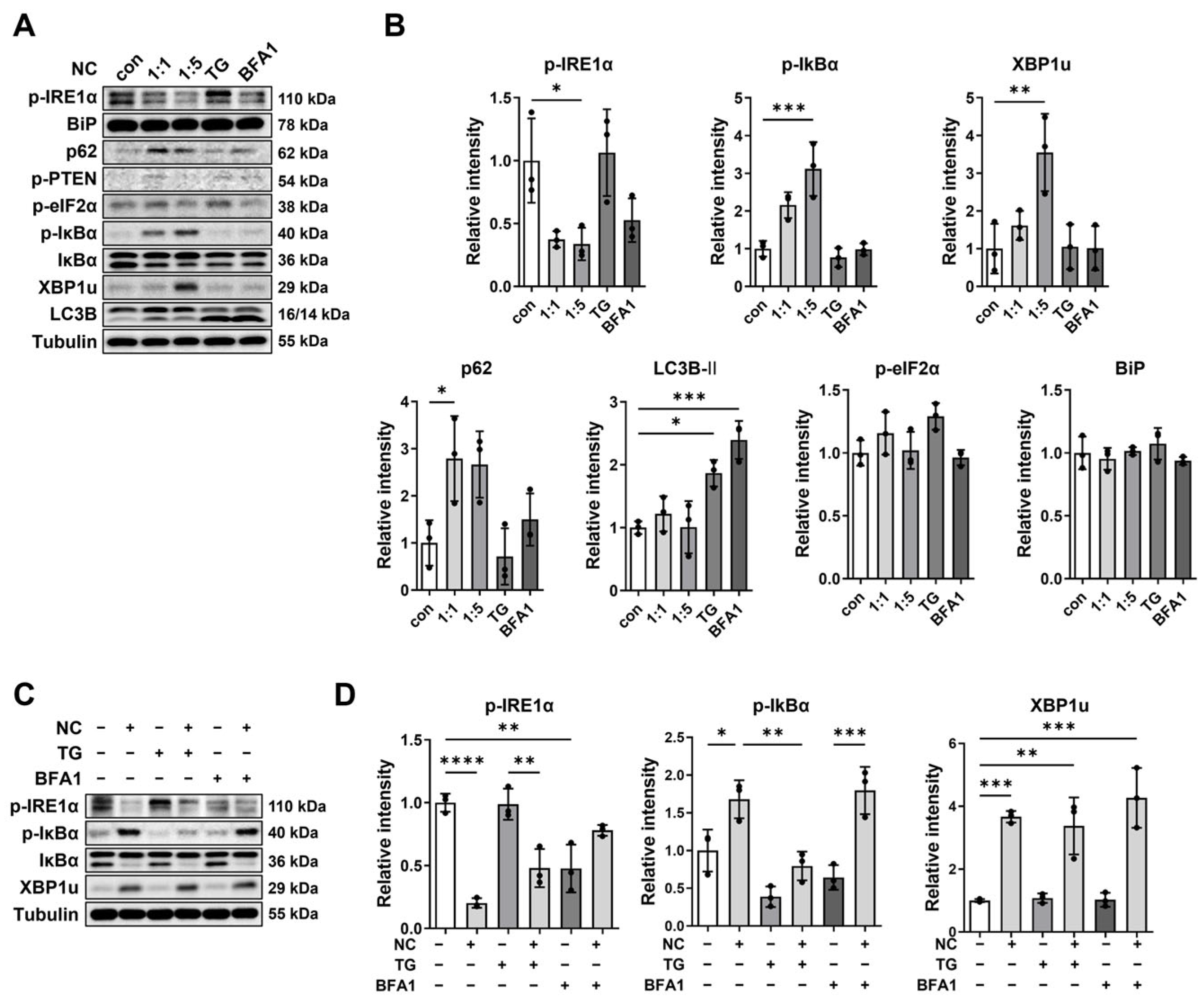

2.2. Necrotic Cell-Induced XBP1u Accumulation Is Independent of TG- or BFA1-Mediated Pathways

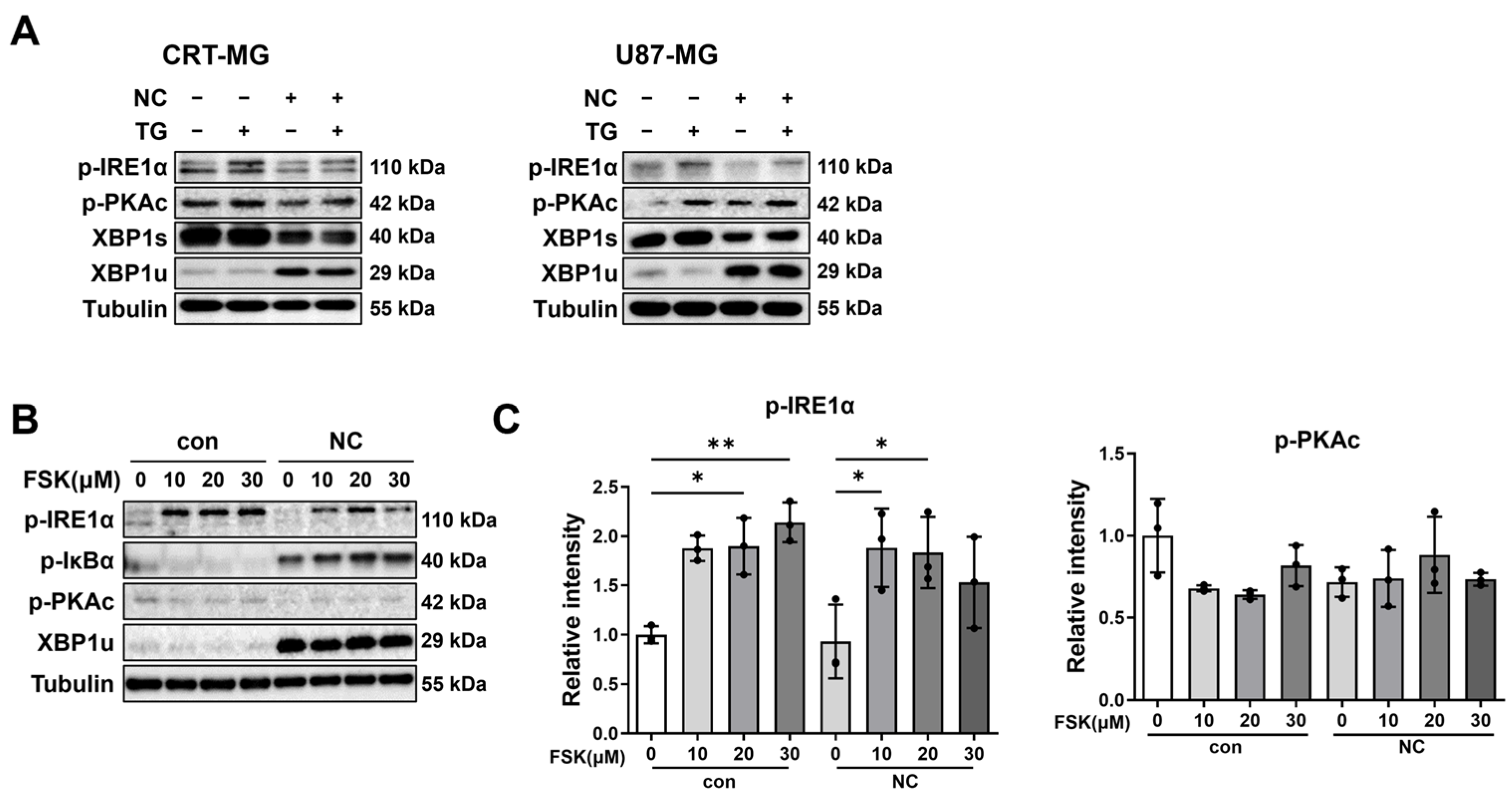

2.3. Necrotic Cells Reduce PKAc and IRE1α Phosphorylation, Leading to Persistent XBP1u Accumulation

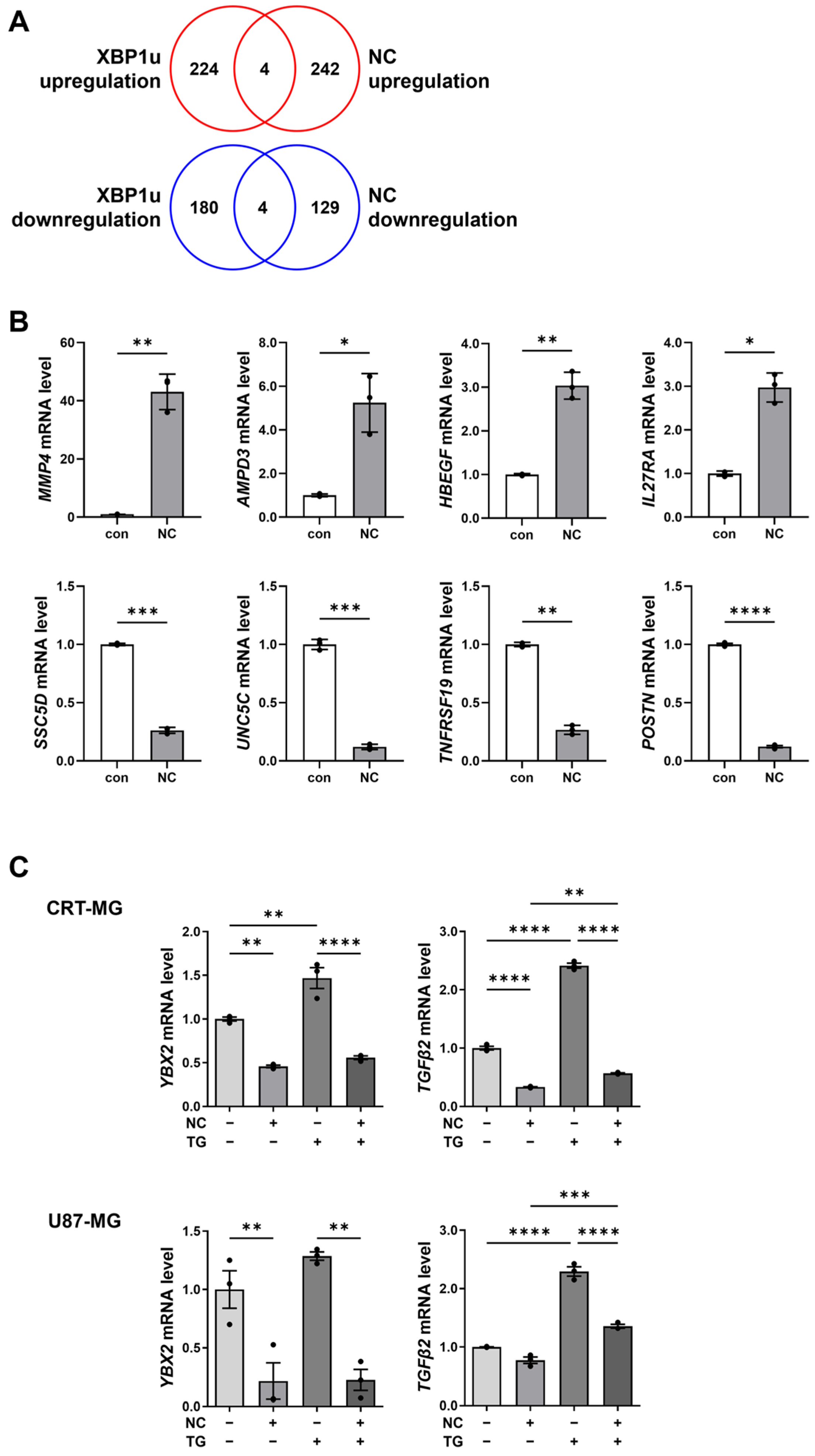

2.4. XBP1u-Regulated Gene Expression in Necrotic Cell-Treated Glioma Cells

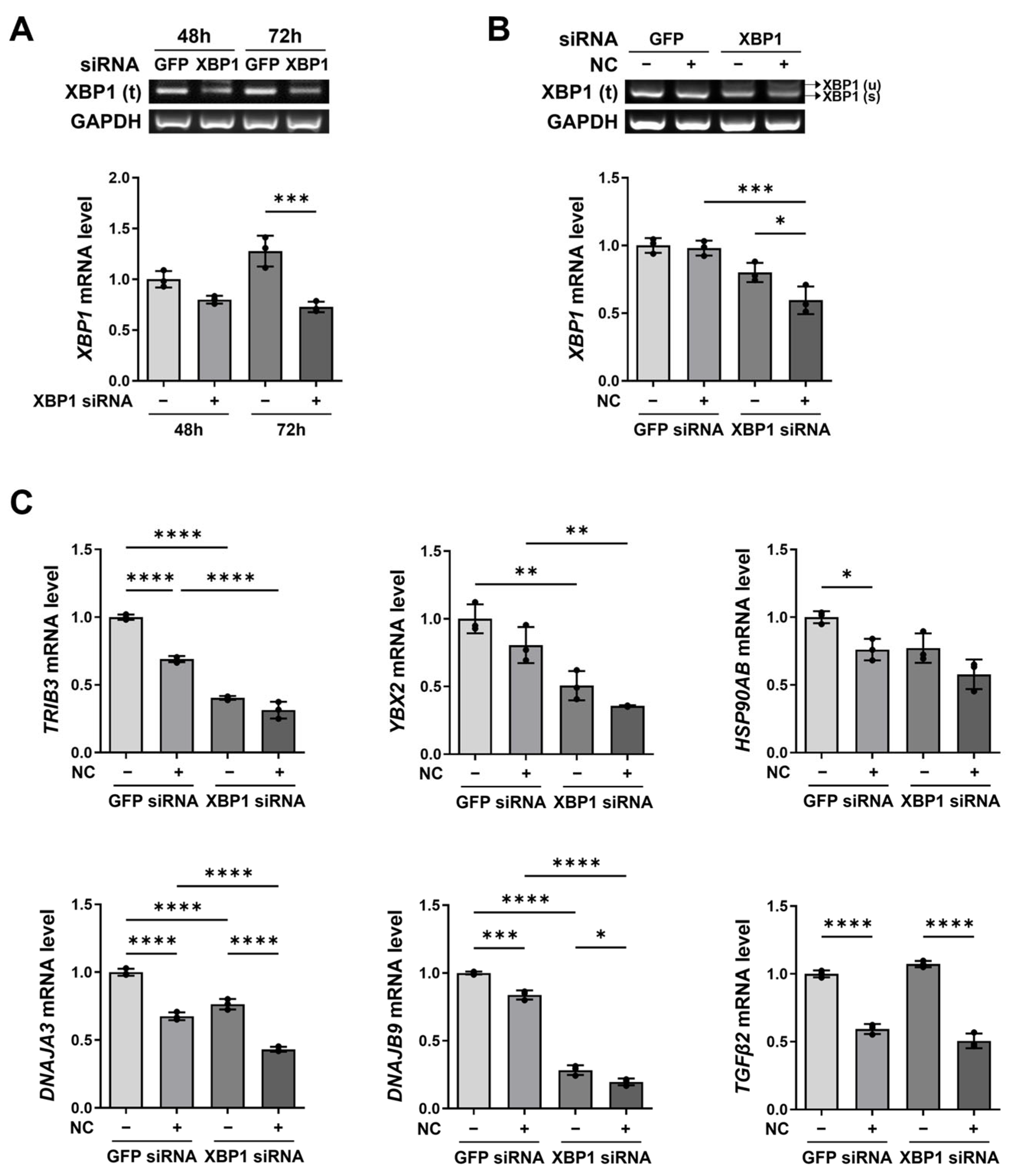

2.5. XBP1 Knockdown and Necrotic Cell Treatment Exert Additive Effects on XBP1-Related Gene Expression

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture and Preparation of Necrotic Cells

4.2. Reagents and Antibodies

4.3. Western Blot Analysis

4.4. Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

4.5. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

4.6. siRNA Transfection

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kiray, H.; Lindsay, S.L.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; Barnett, S.C. The multifaceted role of astrocytes in regulating myelination. Exp. Neurol. 2016, 283, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furnari, F.B.; Fenton, T.; Bachoo, R.M.; Mukasa, A.; Stommel, J.M.; Stegh, A.; Hahn, W.C.; Ligon, K.L.; Louis, D.N.; Brennan, C.; et al. Malignant astrocytic glioma: Genetics, biology, and paths to treatment. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 2683–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.; Ahn, S.H.; Park, H.; Park, S.H.; Choi, K.; Choi, C.; Kang, J.L.; Choi, Y.H. MCP-1 and MIP-3alpha Secreted from Necrotic Cell-Treated Glioblastoma Cells Promote Migration/Infiltration of Microglia. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 48, 1332–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Durden, D.L.; Van Meir, E.G.; Brat, D.J. ‘Pseudopalisading’ necrosis in glioblastoma: A familiar morphologic feature that links vascular pathology, hypoxia, and angiogenesis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2006, 65, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, M.R.; Gupta, A.S.; Mockenhaupt, K.; Brown, L.N.; Biswas, D.D.; Kordula, T. RelB acts as a molecular switch driving chronic inflammation in glioblastoma multiforme. Oncogenesis 2019, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboriak, D.P.; Provenzale, J.M. Evaluation of software for registration of contrast-enhanced brain MR images in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2002, 179, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, E.C. Glioblastoma multiforme: The terminator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 6242–6244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.M.; Lang, F.F.; Aggarwal, B.B.; Fuller, G.N.; Wildrick, D.M.; Sawaya, R. Necrosis and glioblastoma: A friend or a foe? A review and a hypothesis. Neurosurgery 2002, 51, 2–12, discussion 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulda, S.; Gorman, A.M.; Hori, O.; Samali, A. Cellular stress responses: Cell survival and cell death. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 2010, 214074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Jiang, G.; Zhang, P.; Fan, J. Programmed cell death and its role in inflammation. Mil. Med. Res. 2015, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, N.; Talwar, P.; Parimisetty, A.; Lefebvre d’Hellencourt, C.; Ravanan, P. A molecular web: Endoplasmic reticulum stress, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, R.K.; Chae, S.W.; Kim, H.R.; Chae, H.J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and cancer. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 19, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corazzari, M.; Gagliardi, M.; Fimia, G.M.; Piacentini, M. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, Unfolded Protein Response, and Cancer Cell Fate. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, A.D.; Agostinis, P. ER stress, autophagy and immunogenic cell death in photodynamic therapy-induced anti-cancer immune responses. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2014, 13, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pezeshki, A.M.; Yu, X.; Guo, C.; Subjeck, J.R.; Wang, X.Y. The Endoplasmic Reticulum Chaperone GRP170: From Immunobiology to Cancer Therapeutics. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumenis, C. ER stress, hypoxia tolerance and tumor progression. Curr. Mol. Med. 2006, 6, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fels, D.R.; Koumenis, C. The PERK/eIF2alpha/ATF4 module of the UPR in hypoxia resistance and tumor growth. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2006, 5, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebert, M.; Sobolewska, A.; Bartoszewska, S.; Cabaj, A.; Crossman, D.K.; Kroliczewski, J.; Madanecki, P.; Dabrowski, M.; Collawn, J.F.; Bartoszewski, R. Genome-wide mRNA profiling identifies X-box-binding protein 1 (XBP1) as an IRE1 and PUMA repressor. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 7061–7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.H.; Park, H.; Ahn, Y.H.; Kim, S.; Cho, M.S.; Kang, J.L.; Choi, Y.H. Necrotic cells influence migration and invasion of glioblastoma via NF-kappaB/AP-1-mediated IL-8 regulation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Shi, Y.; Oyang, L.; Cui, S.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Peng, M.; Tan, S.; et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-a key guardian in cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murao, A.; Aziz, M.; Wang, H.; Brenner, M.; Wang, P. Release mechanisms of major DAMPs. Apoptosis 2021, 26, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuermans, S.; Kestens, C.; Marques, P.E. Systemic mechanisms of necrotic cell debris clearance. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ron, D. Translational control in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 110, 1383–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, F.; Roman, W.; Bramoulle, A.; Fellmann, C.; Roulston, A.; Shustik, C.; Porco, J.A., Jr.; Shore, G.C.; Sebag, M.; Pelletier, J. Translation initiation factor eIF4F modifies the dexamethasone response in multiple myeloma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13421–13426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesarwani, P.; Kant, S.; Prabhu, A.; Chinnaiyan, P. The interplay between metabolic remodeling and immune regulation in glioblastoma. Neuro-Oncology 2017, 19, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J.E.; Gammoh, N. The impact of autophagy during the development and survival of glioblastoma. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Hu, L.; Yang, K.; Yuan, W.; Shan, D.; Gao, J.; Li, J.; Gimple, R.C.; Dixit, D.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Stress-induced pro-inflammatory glioblastoma stem cells secrete TNFAIP6 to enhance tumor growth and induce suppressive macrophages. Dev. Cell 2025, 60, 2558–2575.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medikonda, R.; Abikenari, M.; Schonfeld, E.; Lim, M. The Metabolic Orchestration of Immune Evasion in Glioblastoma: From Molecular Perspectives to Therapeutic Vulnerabilities. Cancers 2025, 17, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanza, A.; Carlesso, A.; Chintha, C.; Creedican, S.; Doultsinos, D.; Leuzzi, B.; Luis, A.; McCarthy, N.; Montibeller, L.; More, S.; et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling—From basic mechanisms to clinical applications. FEBS J. 2019, 286, 241–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shi, C.; He, M.; Xiong, S.; Xia, X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: Molecular mechanism and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, G.; Vergilio, G.; Paladino, L.; Barone, R.; Cappello, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Macario, A.J.L.; Bucchieri, F.; Rappa, F. The Chaperone System in Breast Cancer: Roles and Therapeutic Prospects of the Molecular Chaperones Hsp27, Hsp60, Hsp70, and Hsp90. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, S.; Tamura, S.; Dubeau, L.; Mhawech-Fauceglia, P.; Miyagi, Y.; Kato, H.; Lieberman, R.; Buckanovich, R.J.; Lin, Y.G.; Neamati, N. Clinicopathological significance of endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins in ovarian carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, C.M.; Talty, A.; Logue, S.E.; Mnich, K.; Gorman, A.M.; Samali, A. An Emerging Role for the Unfolded Protein Response in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangel, D.F.; Dubeau, L.; Park, R.; Chan, P.; Ha, D.P.; Pulido, M.A.; Mullen, D.J.; Vorobyova, I.; Zhou, B.; Borok, Z.; et al. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone GRP78/BiP is critical for mutant Kras-driven lung tumorigenesis. Oncogene 2021, 40, 3624–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Kaplowitz, N.; Lebeaupin, C.; Kroemer, G.; Kaufman, R.J.; Malhi, H.; Ren, J. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in liver diseases. Hepatology 2023, 77, 619–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbilyabo, L.Z.; Yang, L.; Wen, J.; Liu, Z. The unfolded protein response machinery in glioblastoma genesis, chemoresistance and as a druggable target. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Choi, J.H.; Park, E.M.; Choi, Y.H. Interaction of promyelocytic leukemia/p53 affects signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 activity in response to oncostatin M. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2020, 24, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene (Human) | Sequence | Tm (°C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-PCR primer | XBP1 | Forward | 5′-CCTGGTTGCTGAAGAGGAGG-3′ | 60.04 |

| Reverse | 5′-CCATGGGGAGATGTTCTGGAG-3′ | 59.86 | ||

| GAPDH | Forward | 5′-TGGAAATCCCATCACCATCT-3′ | 56.17 | |

| Reverse | 5′-GTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGAT-3′ | 59.67 | ||

| qRT-PCR primer | DNAJA3 | Forward | 5′-AGGAGGGATTCCTTTCCAAACTTA-3′ | 59.39 |

| Reverse | 5′-TCTGGAATCCTCCCGTCTCC-3′ | 60.40 | ||

| DNAJB9 | Forward | 5′-GCCATGAAGTACCACCCTGACA-3′ | 62.27 | |

| Reverse | 5′-TCGTCTATTAGCATCTGAGAGTGT-3′ | 58.87 | ||

| HSP90AB | Forward | 5′-TTGGGTATCGGAAAGCAAGCC-3′ | 60.95 | |

| Reverse | 5′-GTGCACTTCCTCAGGCATCTTG-3′ | 61.77 | ||

| TGFβ2 | Forward | 5′-ACACTCAGCACAGCAGGGTCCT-3′ | 65.86 | |

| Reverse | 5′-TTGGGACACGCAGCAAGGAGAAG-3′ | 65.32 | ||

| TRIB3 | Forward | 5′-AGCGGTTGGAGTTGGATGACA-3′ | 61.99 | |

| Reverse | 5′-GGCCACAGCAGTTGCACGA-3′ | 63.75 | ||

| YBX2 | Forward | 5′-GATGTCGTGGAAGGAGAGAAGG-3′ | 60.16 | |

| Reverse | 5′-GATGAATCGGCGGGACTTACGT-3′ | 62.72 | ||

| MPP4 | Forward | 5′-TAGCCAGCAGATGGTGTACGTC-3′ | 62.10 | |

| Reverse | 5′-GGTCCACAATCTGGAGGATGTC-3′ | 60.42 | ||

| AMPD3 | Forward | 5′-CTGGTTCATCCAGCACAAGGTC-3′ | 61.45 | |

| Reverse | 5′-GGCAGGAAGATGTTCTCCAGGA-3′ | 61.75 | ||

| HBEGF | Forward | 5′-TGTATCCACGACCAGCTGCTA-3′ | 60.96 | |

| Reverse | 5′-TGCTCCTCCTTGTTTGGTGTGG-3′ | 62.98 | ||

| UNC5C | Forward | 5′-AGAATGGAGGCAAGGACTGCGA-3′ | 63.98 | |

| Reverse | 5′-GCCAGGCAAACGATCACTGCTA-3′ | 63.44 | ||

| SSC5D | Forward | 5′-TGTGACTGCCAGTGTTCTGGAG-3′ | 62.44 | |

| Reverse | 5′-GGAGTGTTTCGTGGTTGGCATC-3′ | 62.27 | ||

| TNFRSF19 | Forward | 5′-GGTGCATTCTGCAGCCAGTCTT-3′ | 63.67 | |

| Reverse | 5′-CAGGCATCTGAAAACTCGCCAC-3′ | 62.32 | ||

| POSTN | Forward | 5′-CAGCAAACCACCTTCACGGATC-3′ | 62.02 | |

| Reverse | 5′-TTAAGGAGGCGCTGAACCATGC-3′ | 63.46 | ||

| IL27RA | Forward | 5′-GTGTGGGTATCAGGGAACCTCT-3′ | 61.16 | |

| Reverse | 5′-TCCTTCTGGACTCAGCTCACGA-3′ | 62.79 | ||

| GAPDH | Forward | 5′-GAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT-3′ | 58.21 | |

| Reverse | 5′-AATGAAGGGGTCATTGATGG-3′ | 55.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lim, J.; Lee, S.; Hong, Y.-S.; Choi, J.H.; Jo, A.; Kang, J.L.; Song, T.-J.; Choi, Y.-H. Necrotic Cells Alter IRE1α-XBP1 Signaling and Induce Transcriptional Changes in Glioblastoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010474

Lim J, Lee S, Hong Y-S, Choi JH, Jo A, Kang JL, Song T-J, Choi Y-H. Necrotic Cells Alter IRE1α-XBP1 Signaling and Induce Transcriptional Changes in Glioblastoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):474. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010474

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Jiwoo, Seulgi Lee, Ye-Seon Hong, Ji Ha Choi, Ala Jo, Jihee Lee Kang, Tae-Jin Song, and Youn-Hee Choi. 2026. "Necrotic Cells Alter IRE1α-XBP1 Signaling and Induce Transcriptional Changes in Glioblastoma" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010474

APA StyleLim, J., Lee, S., Hong, Y.-S., Choi, J. H., Jo, A., Kang, J. L., Song, T.-J., & Choi, Y.-H. (2026). Necrotic Cells Alter IRE1α-XBP1 Signaling and Induce Transcriptional Changes in Glioblastoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 474. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010474