Scutellaria lateriflora Extract Supplementation Provides Resilience to Age-Related Phenotypes in Drosophila melanogaster

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

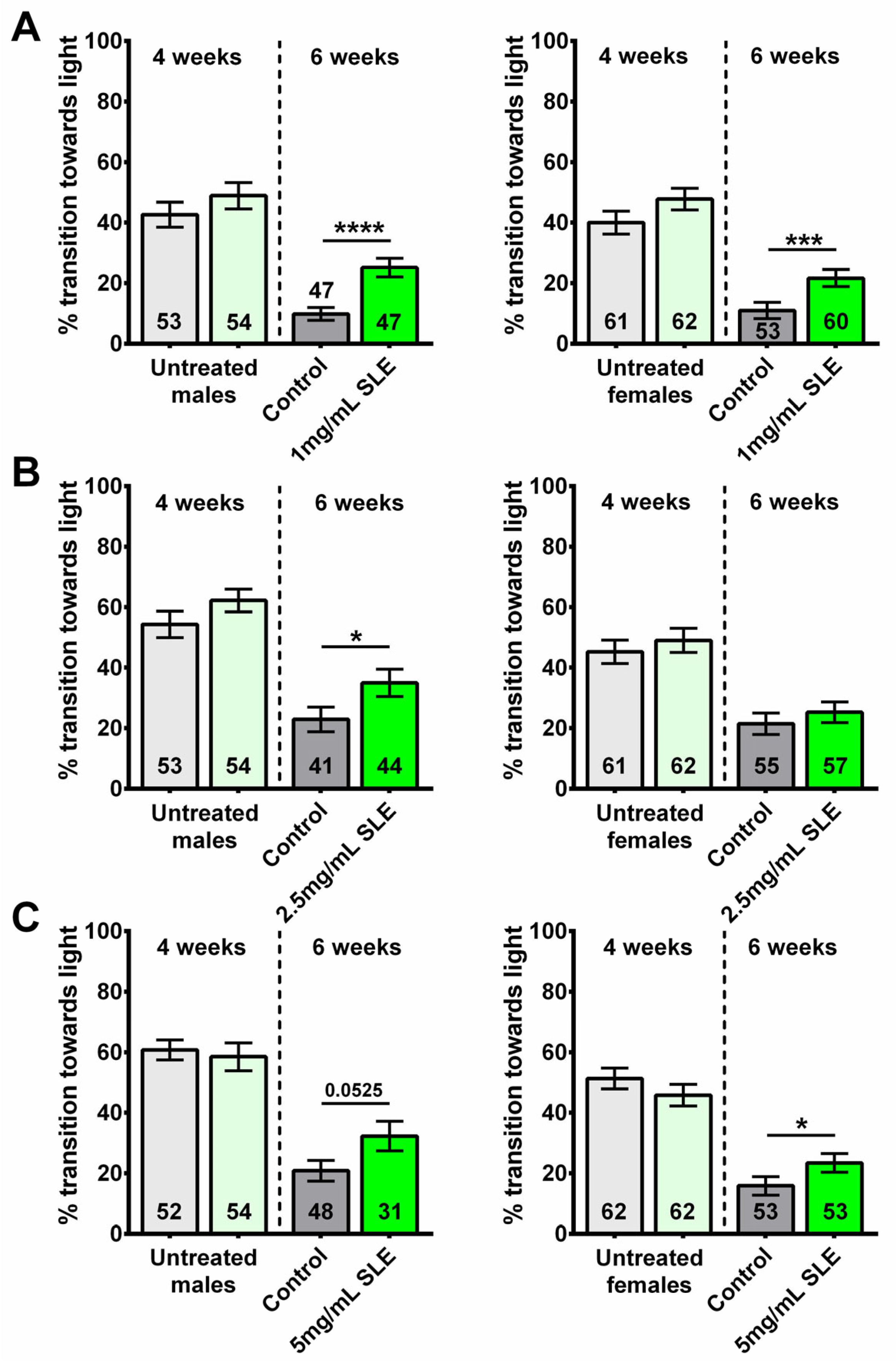

2.1. S. lateriflora (SL) Treatment Improves Phototaxis

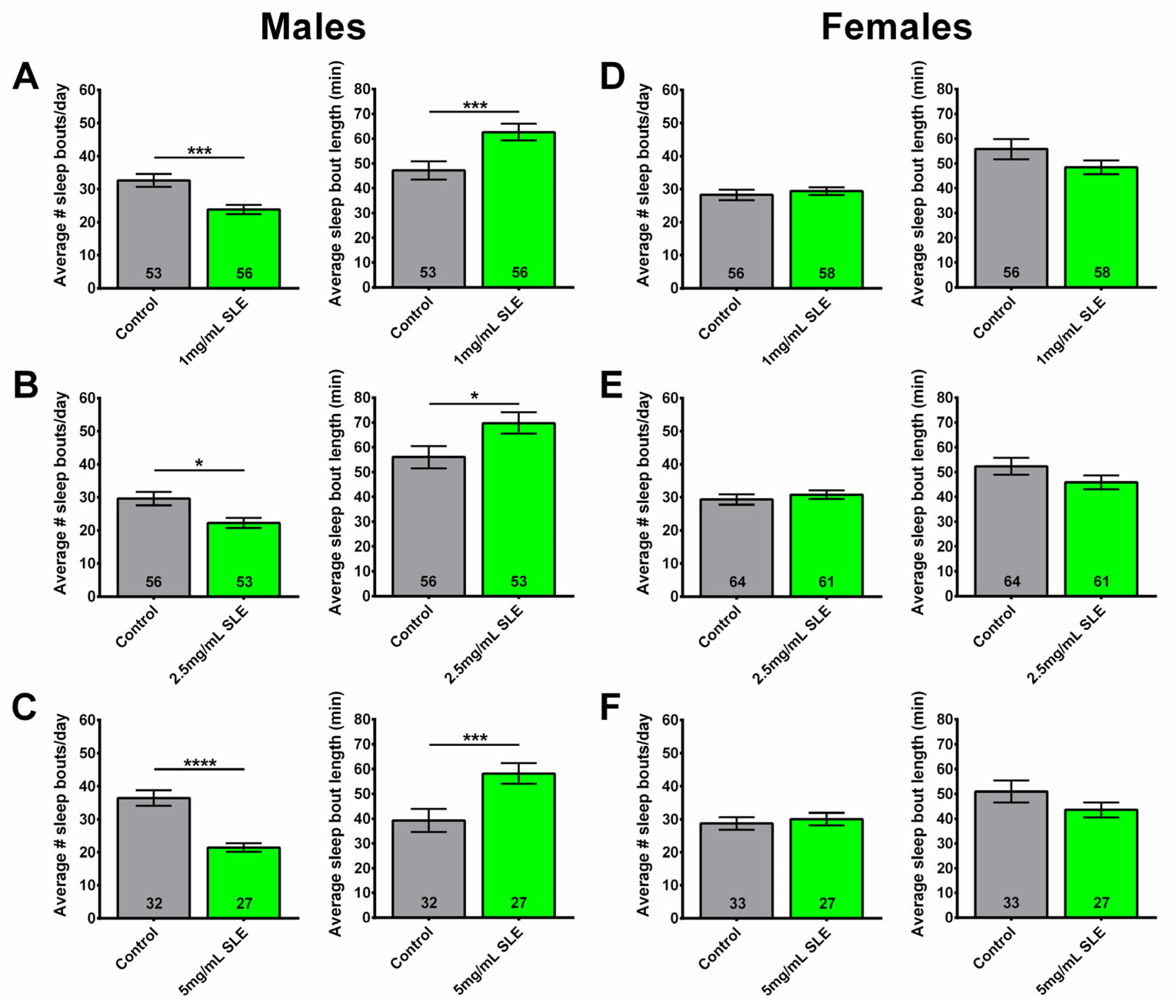

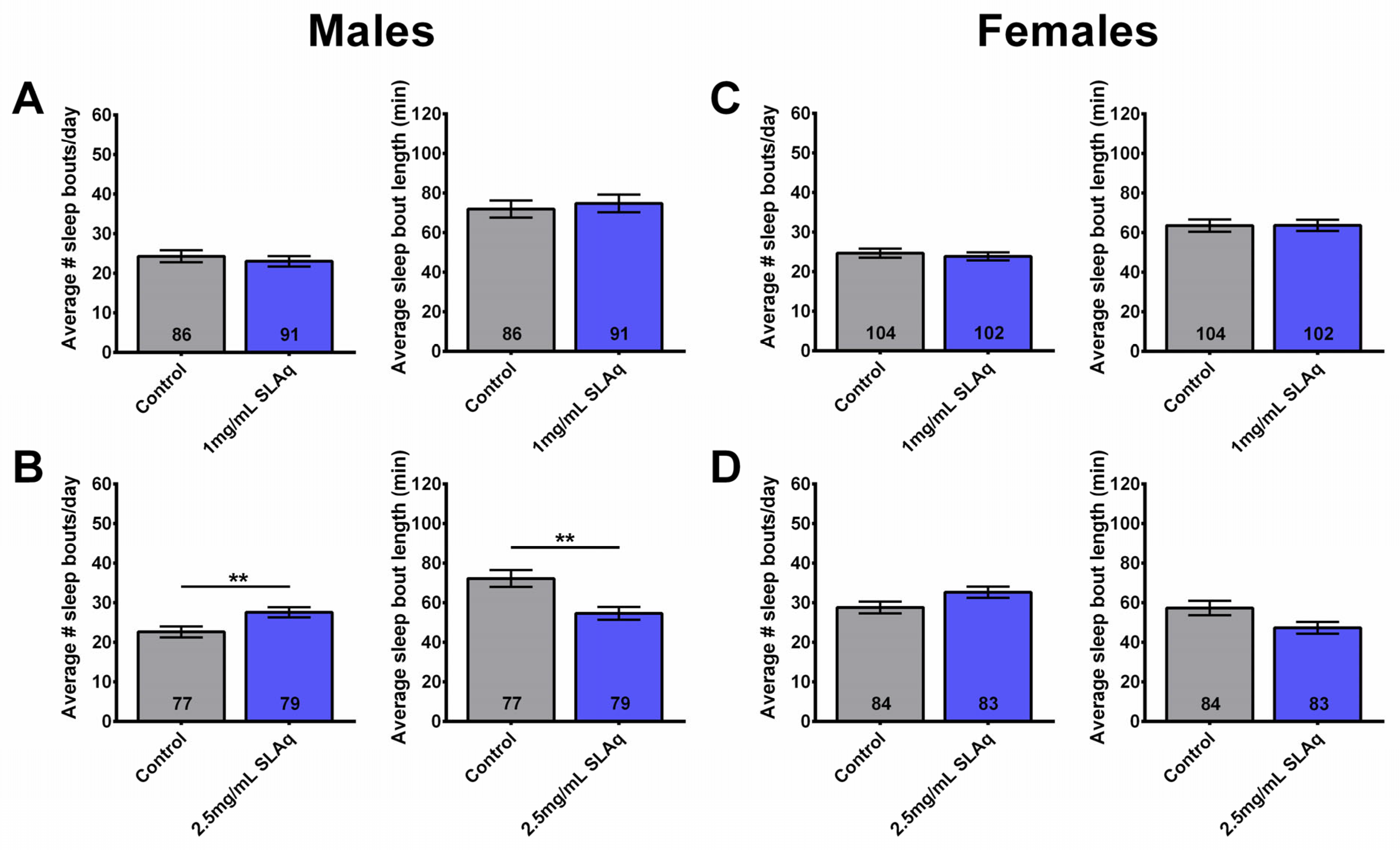

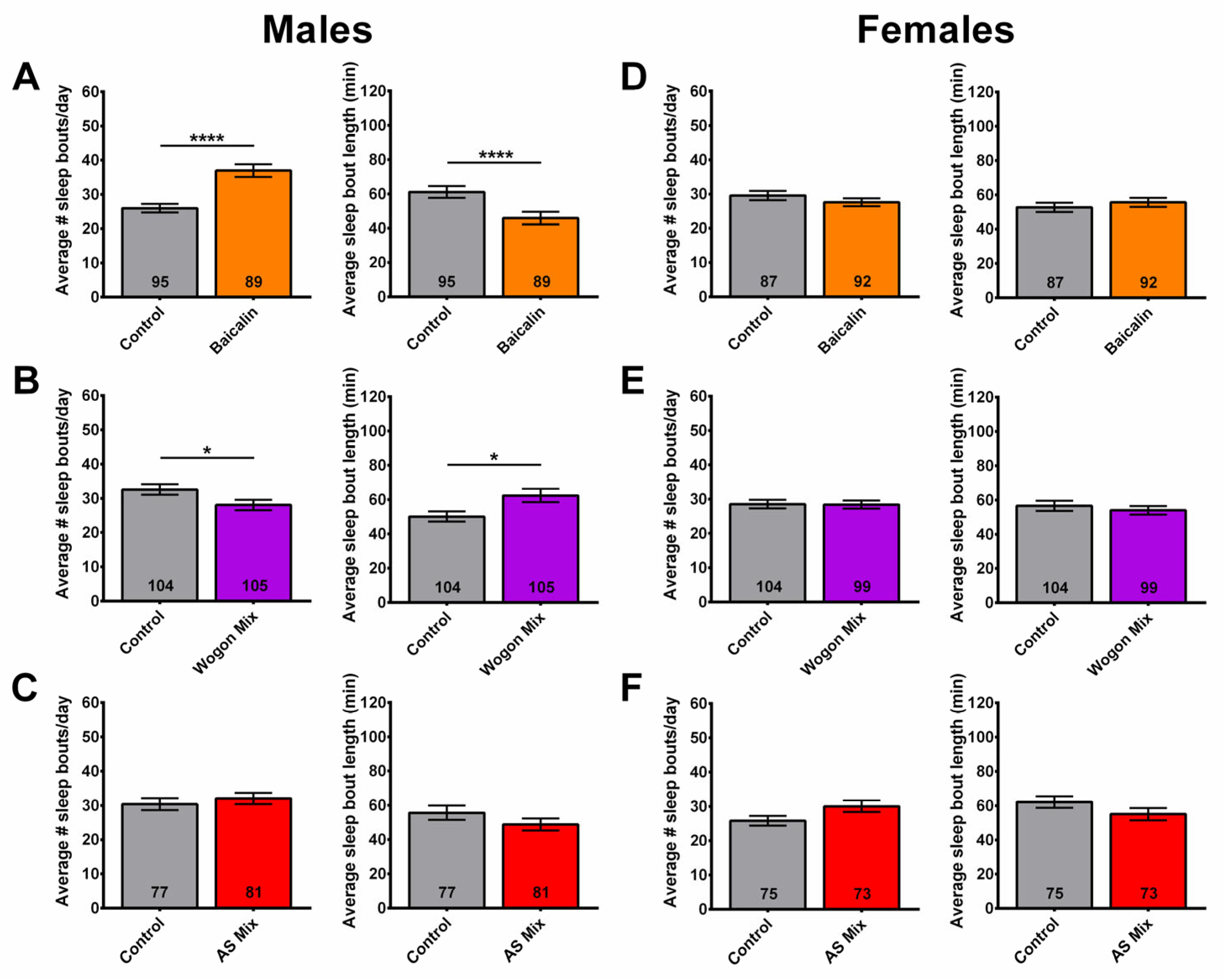

2.2. Sleep Fragmentation Is Reduced in Males Given the Ethanol Extract of SL

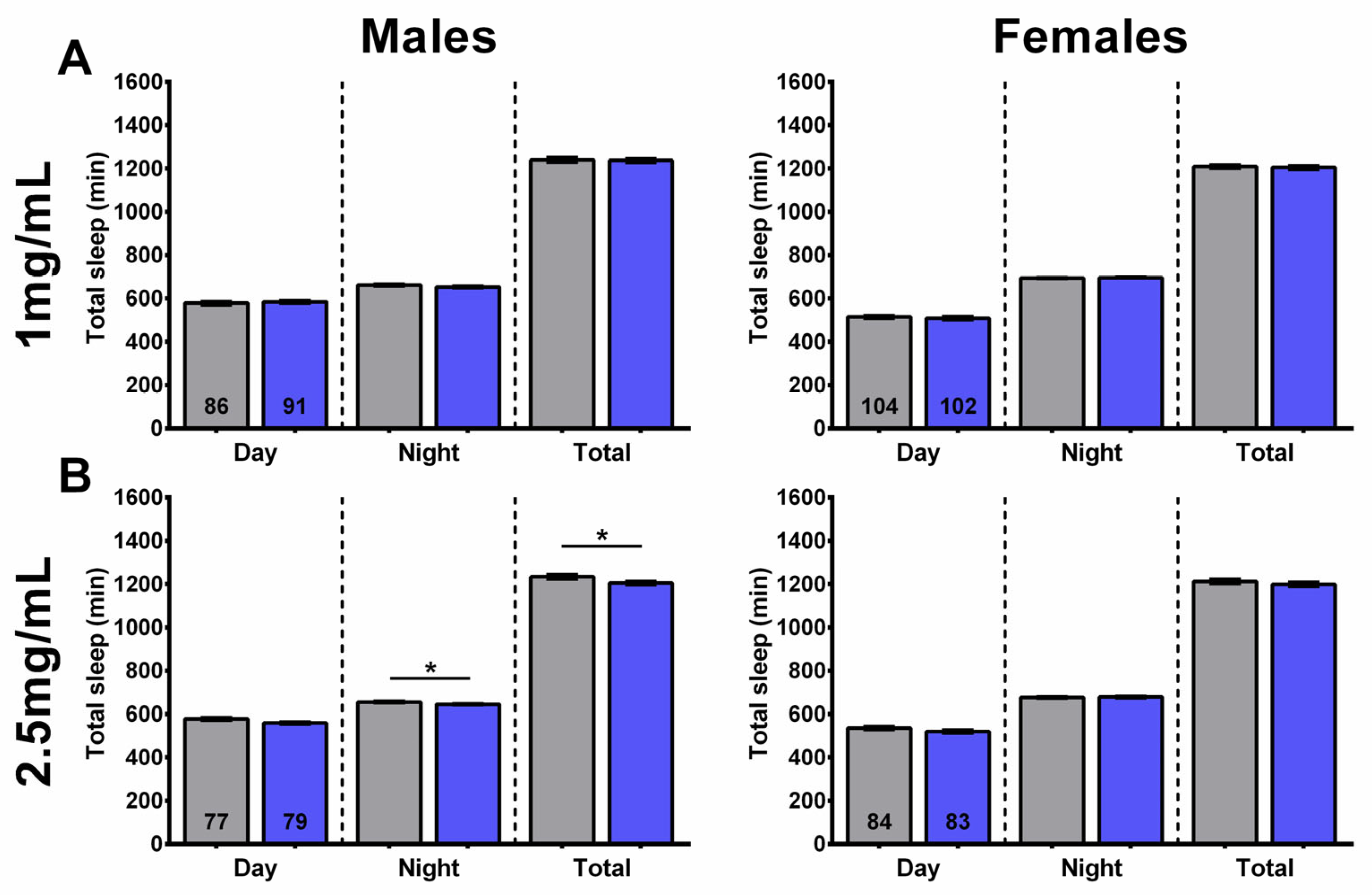

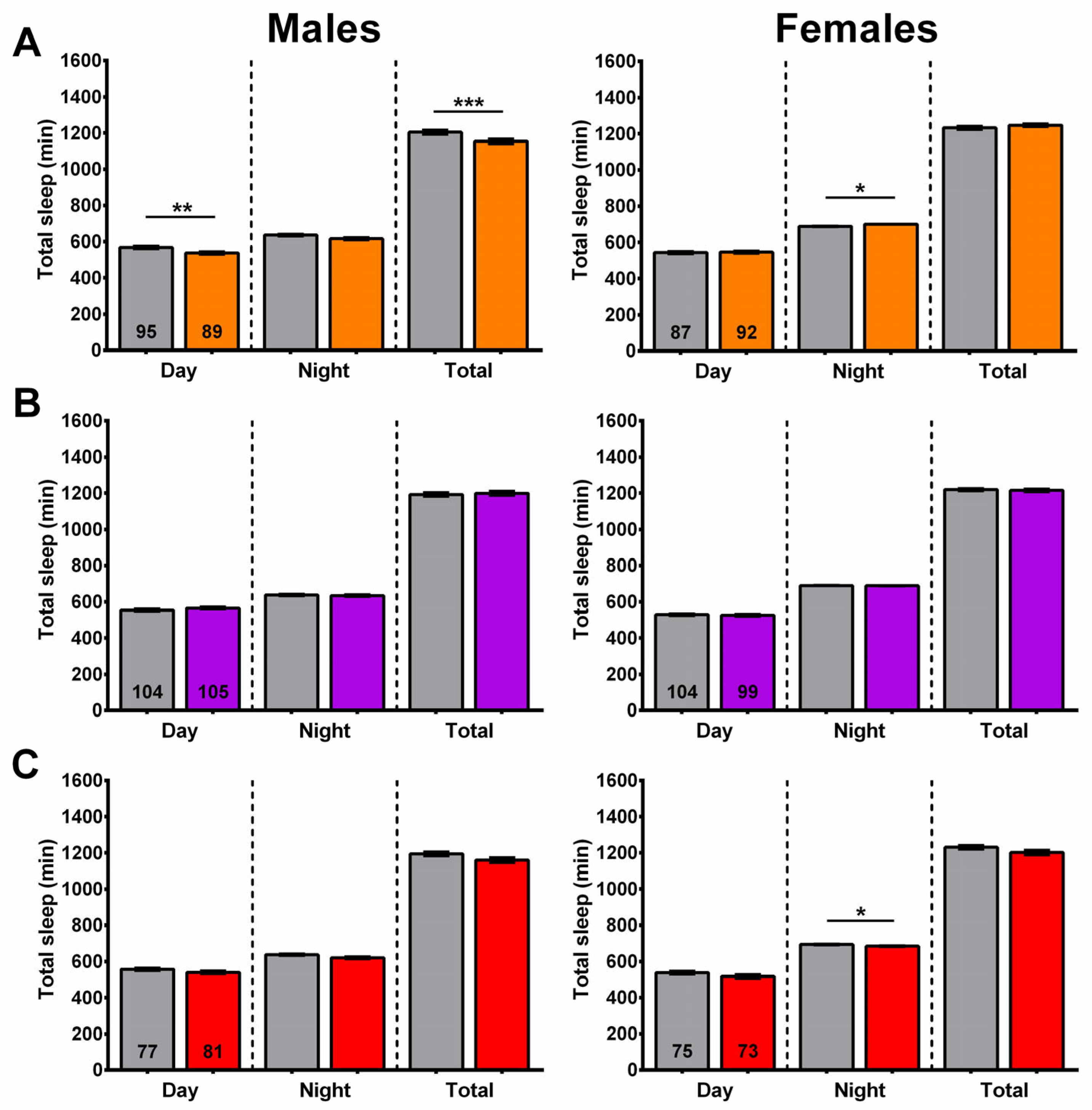

2.3. SLE Increased Nighttime Sleep

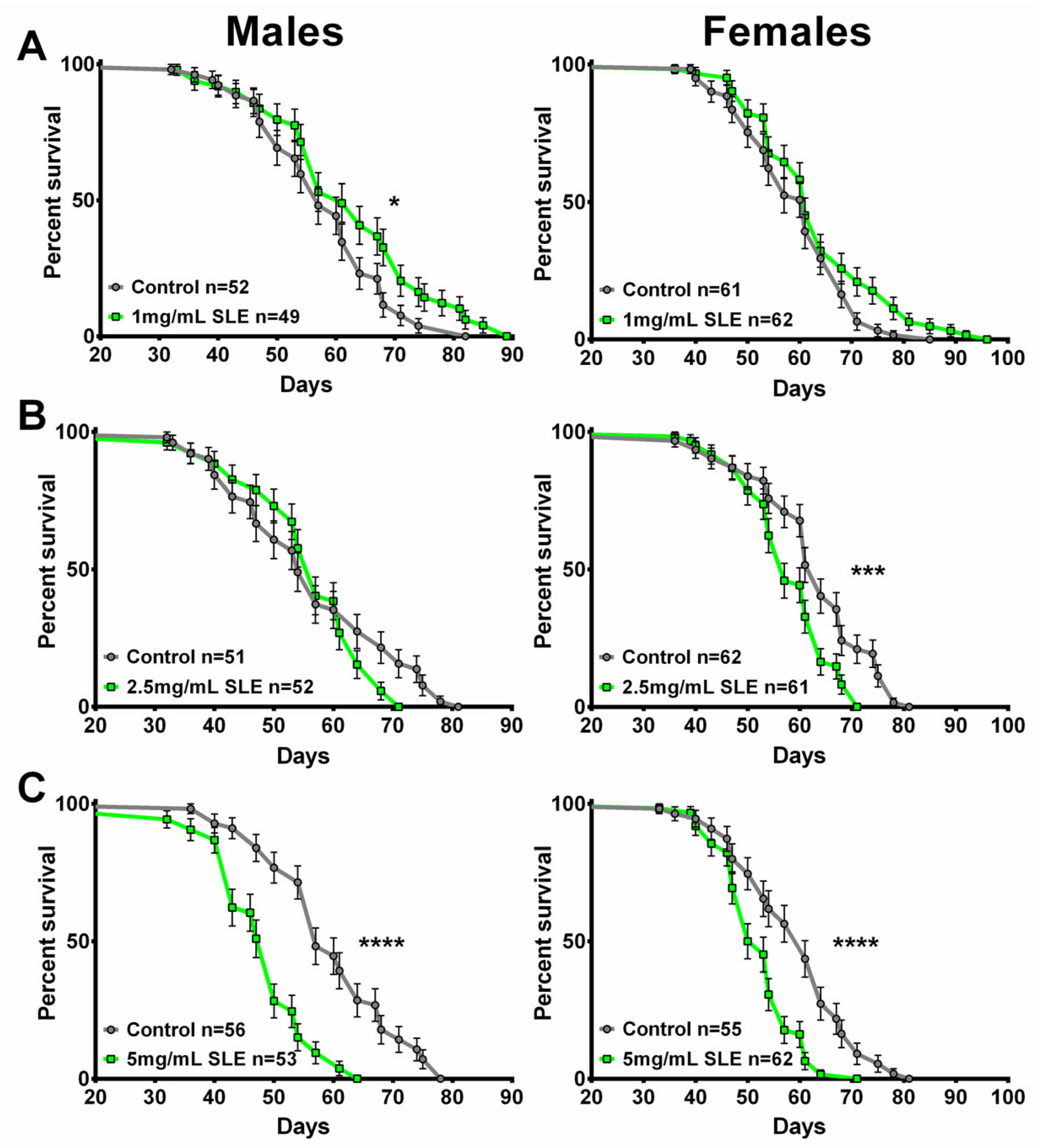

2.4. SL Supplementation Did Not Extend Longevity

2.5. SLE Reduces Neurodegeneration

2.6. LC-MS Identification and Quantification of 10 Flavonoids in SLE and SLAq

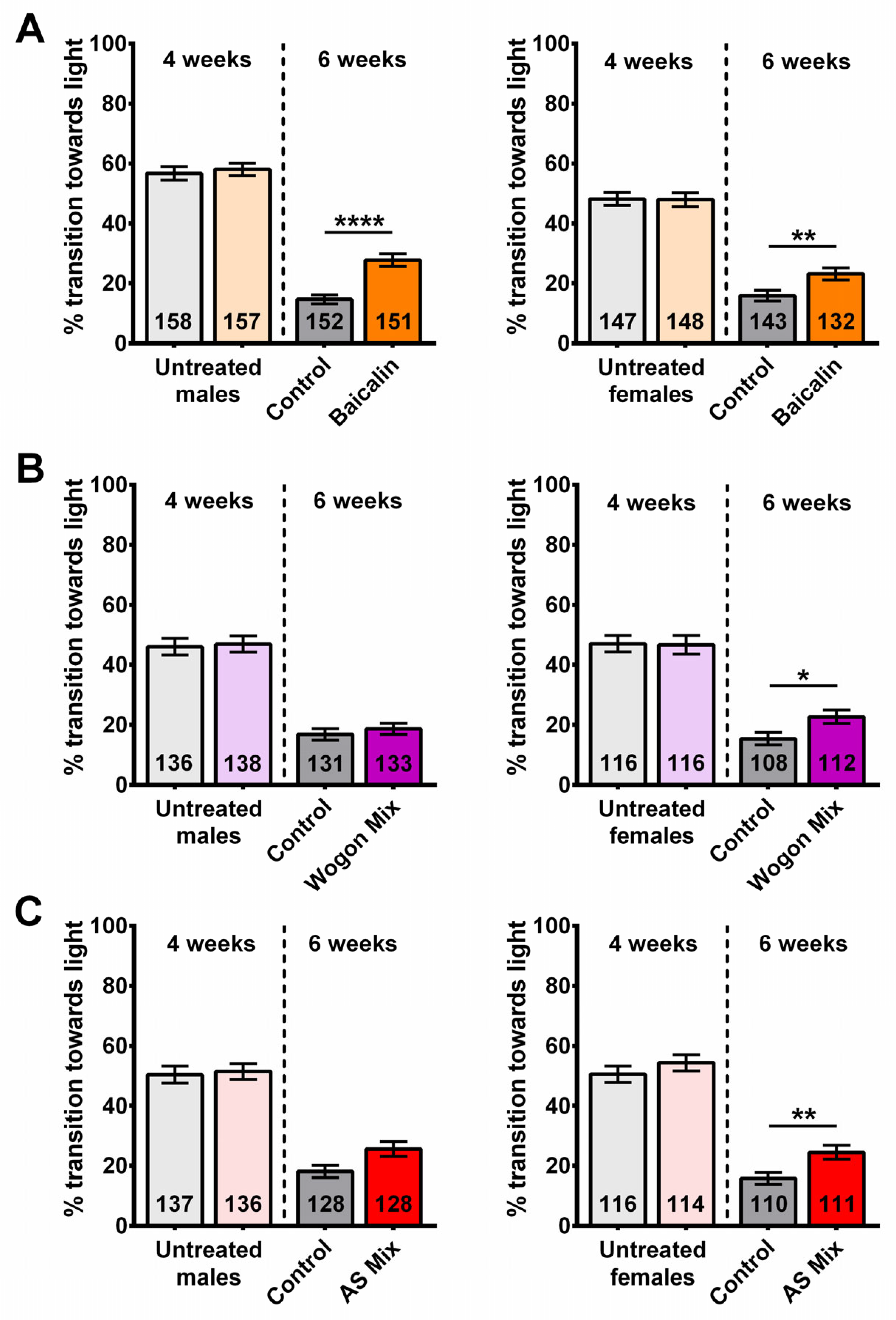

2.7. Compound Supplementation Improved Performance in Phototaxis

2.8. Wogon Mix Treatment Reduced Sleep Fragmentation in Males

2.9. Wogon Mix Treatment Has No Effect on Sleep Timing

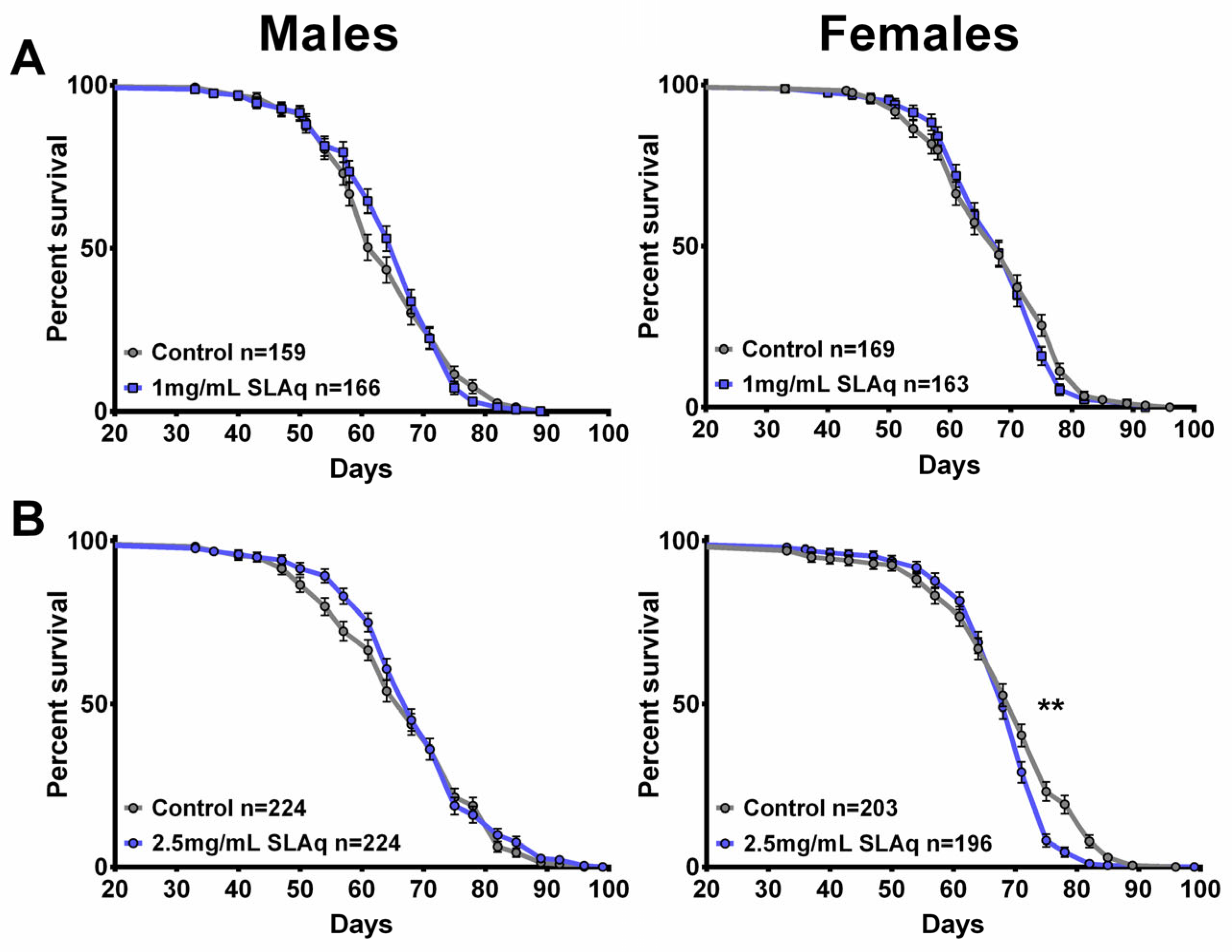

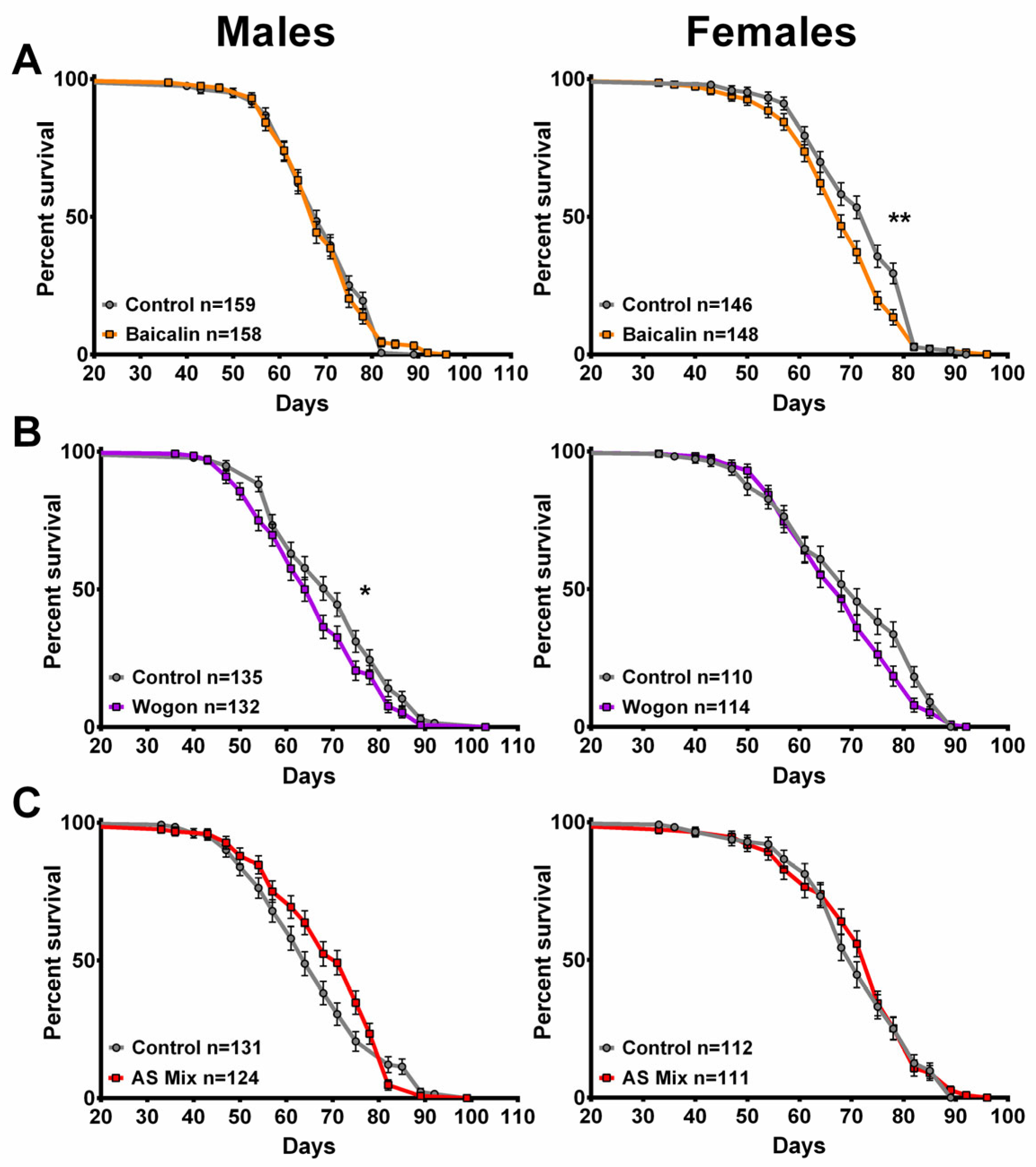

2.10. Longevity

2.11. The Neurodegeneration Was Not Improved by the Tested Compounds

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Drosophila Melanogaster Stocks

4.2. Raw Plant Material and Extracts

4.3. Chemicals and Reagents

4.4. Preparation of Scutellaria lateriflora Extracts and LC-MS/MS Method Calibrators

4.5. LC-MS/MS Analysis for S. lateriflora Extracts

4.6. Diets

4.7. Fast Phototaxis

4.8. Sleep

4.9. Lifespan

4.10. Neurodegeneration

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rocca, W.A.; Petersen, R.C.; Knopman, D.S.; Hebert, L.E.; Evans, D.A.; Hall, K.S.; Gao, S.; Unverzagt, F.W.; Langa, K.M.; Larson, E.B.; et al. Trends in the incidence and prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and cognitive impairment in the United States. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011, 7, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazer, D.G.; Yaffe, K.; Karlawish, J. Cognitive aging: A report from the Institute of Medicine. JAMA 2015, 313, 2121–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdanys, K.F.; Steffens, D.C. Sleep Disturbances in the Elderly. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 38, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benca, R.M.; Teodorescu, M. Sleep physiology and disorders in aging and dementia. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2019, 167, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooneratne, N.S.; Vitiello, M.V. Sleep in older adults: Normative changes, sleep disorders, and treatment options. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2014, 30, 591–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niccoli, T.; Partridge, L. Ageing as a risk factor for disease. Curr. Biol. 2012, 22, R741–R752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, A.S.; Yu, L.; Costa, M.D.; Leurgans, S.E.; Buchman, A.S.; Bennett, D.A.; Saper, C.B. Increased fragmentation of rest-activity patterns is associated with a characteristic pattern of cognitive impairment in older individuals. Sleep 2012, 35, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, A.; Ji, S.; Lai, W.; Hu, D.; Wang, M.; Zhao, X.; Chen, L. The bidirectional relationship between sleep disturbance and anxiety: Sleep disturbance is a stronger predictor of anxiety. Sleep Med. 2024, 121, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wennberg, A.M.V.; Wu, M.N.; Rosenberg, P.B.; Spira, A.P. Sleep Disturbance, Cognitive Decline, and Dementia: A Review. Semin. Neurol. 2017, 37, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, U.; Sehar, U.; Brownell, M.; Reddy, P.H. Mechanisms, consequences and role of interventions for sleep deprivation: Focus on mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease in elderly. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 100, 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeck, J.L.; Ford, J.; Conway, E.L.; Kurtzhalts, K.E.; Gee, M.E.; Vollmer, K.A.; Mergenhagen, K.A. Review of Safety and Efficacy of Sleep Medicines in Older Adults. Clin. Ther. 2016, 38, 2340–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borras, S.; Martinez-Solis, I.; Rios, J.L. Medicinal Plants for Insomnia Related to Anxiety: An Updated Review. Planta Med. 2021, 87, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, C.; Li, R.; Lyketsos, C.; Livingston, G. Treatment for mild cognitive impairment: Systematic review. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 203, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, S.; Fujishiro, H.; Takechi, H. Efficacy and Safety of Cholinesterase Inhibitors for Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2019, 71, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setzer, W.N. The Phytochemistry of Cherokee Aromatic Medicinal Plants. Medicines 2018, 5, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Li, P.; Liu, S.; Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; He, C.; Xiao, P. Traditional uses, ten-years research progress on phytochemistry and pharmacology, and clinical studies of the genus Scutellaria. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 265, 113198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergeron, C.; Gafner, S.; Clausen, E.; Carrier, D.J. Comparison of the chemical composition of extracts from Scutellaria lateriflora using accelerated solvent extraction and supercritical fluid extraction versus standard hot water or 70% ethanol extraction. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3076–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.H.; Joshee, N. Current status of research on medicinal plant Scutellaria lateriflora: A review. J. Med. Aromat. Plants 2022, 11, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohani, M.; Ahuja, M.; Buabeid, M.A.; Schwartz, D.; Shannon, D.; Suppiramaniam, V.; Kemppainen, B.; Dhanasekaran, M. Anti-oxidative and DNA Protecting Effects of Flavonoids-rich Scutellaria lateriflora. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2013, 8, 1934578X1300801019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.; Duke, J.A. A Field Guide to Medicinal Plants: Eastern and Central North America, Expanded ed.; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1990; p. 366. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, C.; Whitehouse, J.; Tewfik, I.; Towell, T. The use of Scutellaria lateriflora: A pilot survey amongst herbal medicine practitioners. J. Herb. Med. 2012, 2, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfson, P.; Hoffmann, D.L. An investigation into the efficacy of Scutellaria lateriflora in healthy volunteers. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 2003, 9, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, C.; Whitehouse, J.; Tewfik, I.; Towell, T. American Skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora): A randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study of its effects on mood in healthy volunteers. Phytother. Res. 2014, 28, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Minno, A.; Morone, M.V.; Buccato, D.G.; De Lellis, L.F.; Ullah, H.; Piccinocchi, R.; Cordara, M.; Larsen, D.S.; Di Guglielmo, A.; Baldi, A. Efficacy and Tolerability of a Chemically Characterized Scutellaria lateriflora L. Extract-Based Food Supplement for Sleep Management: A Single-Center, Controlled, Randomized, Crossover, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Minno, A.; Ullah, H.; De Lellis, L.F.; Buccato, D.G.; Baldi, A.; Cuomo, P.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Khalifa, S.A.M.; Xiao, X.; Piccinocchi, R.; et al. Efficacy and Tolerability of a Scutellaria lateriflora L. and Cistus × incanus L.-Based Chewing Gum on the Symptoms of Gingivitis: A Monocentric, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurul Islam, M.; Downey, F.; Ng, C.K. Comparative analysis of bioactive phytochemicals from Scutellaria baicalensis, Scutellaria lateriflora, Scutellaria racemosa, Scutellaria tomentosa and Scutellaria wrightii by LC-DAD-MS. Metabolomics 2011, 7, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costine, B.; Zhang, M.; Chhajed, S.; Pearson, B.; Chen, S.; Nadakuduti, S.S. Exploring native Scutellaria species provides insight into differential accumulation of flavones with medicinal properties. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makino, T.; Hishida, A.; Goda, Y.; Mizukami, H. Comparison of the major flavonoid content of S. baicalensis, S. lateriflora, and their commercial products. J. Nat. Med. 2008, 62, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nobrega, A.K.; Lyons, L.C. Aging and the clock: Perspective from flies to humans. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2020, 51, 454–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, A.; MacKay, D. Health habits and other characteristics of dietary supplement users: A review. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holvoet, H.; Long, D.M.; Law, A.; McClure, C.; Choi, J.; Yang, L.; Marney, L.; Poeck, B.; Strauss, R.; Stevens, J.F.; et al. Withania somnifera Extracts Promote Resilience against Age-Related and Stress-Induced Behavioral Phenotypes in Drosophila melanogaster; a Possible Role of Other Compounds besides Withanolides. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliadi, K.G.; Boulianne, G.L. Age-related behavioral changes in Drosophila. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1197, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliadi, K.G.; Knight, D.; Boulianne, G.L. Healthy aging–insights from Drosophila. Front. Physiol. 2012, 3, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, B.; Kryger, M.H. Sleep in the Aging Population. Sleep Med. Clin. 2017, 12, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K.; Evans, J.M.; Hendricks, J.C.; Sehgal, A. A Drosophila model for age-associated changes in sleep: Wake cycles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 13843–13847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, T.R.; Chow, E.S.; Law, A.D.; Fu, S.D.; Fuszara, E.; Bilska, A.; Bebas, P.; Kretzschmar, D.; Giebultowicz, J.M. Daily blue-light exposure shortens lifespan and causes brain neurodegeneration in Drosophila. NPJ Aging Mech. Dis. 2019, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EghbaliFeriz, S.; Taleghani, A.; Tayarani-Najaran, Z. Central nervous system diseases and Scutellaria: A review of current mechanism studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 102, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, B.; Venditti, A.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Kregiel, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Santini, A.; Souto, E.B.; Novellino, E.; et al. The Therapeutic Potential of Apigenin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Li, C. Review on the pharmacological effects and pharmacokinetics of scutellarein. Arch. Pharm. 2024, 357, e2400053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upton, R.; Dayu, R.H. Skullcap Scutellaria lateriflora L.: An American nervine. J. Herb. Med. 2012, 2, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, R.S.M.; Duarte, F.S.; de Lima, T.C.M. Involvement of GABAergic non-benzodiazepine sites in the anxiolytic-like and sedative effects of the flavonoid baicalein in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 221, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, R.; Arnason, J.T.; Trudeau, V.; Bergeron, C.; Budzinski, J.W.; Foster, B.C.; Merali, Z. Phytochemical and biological analysis of skullcap (Scutellaria lateriflora L.): A medicinal plant with anxiolytic properties. Phytomedicine 2003, 10, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Shing, M.; Huen, Y.; Tsang, S.Y.; Xue, H. Neuroactive flavonoids interacting with GABAA receptor complex. Curr. Drug Targets CNS Neurol. Disord. 2005, 4, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiden, M.; Leidel, F.; Strohmeier, B.; Fast, C.; Groschup, M.H. A Medicinal Herb Scutellaria lateriflora Inhibits PrP Replication in vitro and Delays the Onset of Prion Disease in Mice. Front. Psychiatry 2012, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, F.; Weishaupt, R.; Katumba, P.K.M.; Elcoate, R.; Wightman, E. Effects of a Scutellaria baicalensis/Crataegus laevigata, magnesium and chromium supplement on stressed individuals: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 2025, 39, 02698811251381261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.-H.; Yi, P.-L.; Cheng, C.-H.; Lu, C.-Y.; Hsiao, Y.-T.; Tsai, Y.-F.; Li, C.-L.; Chang, F.-C. Biphasic effects of baicalin, an active constituent of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, in the spontaneous sleep–wake regulation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 135, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, A.D.; Cassar, M.; Long, D.M.; Chow, E.S.; Giebultowicz, J.M.; Venkataramanan, A.; Strauss, R.; Kretzschmar, D. FTD-associated mutations in Tau result in a combination of dominant and recessive phenotypes. Neurobiol. Dis. 2022, 170, 105770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzer, S. Behavioral mutants of Drosophila isolated by countercurrent distribution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1967, 58, 1112–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendricks, J.C.; Finn, S.M.; Panckeri, K.A.; Chavkin, J.; Williams, J.A.; Sehgal, A.; Pack, A.I. Rest in Drosophila is a sleep-like state. Neuron 2000, 25, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, P.J.; Cirelli, C.; Greenspan, R.J.; Tononi, G. Correlates of sleep and waking in Drosophila melanogaster. Science 2000, 287, 1834–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderhaus, E.R.; Kretzschmar, D. Mass Histology to Quantify Neurodegeneration in Drosophila. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, 118, e54809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | µg/mg SLE | µg/mg SLAq |

|---|---|---|

| Baicalin | 97.5358 | 91.9381 |

| Wogonoside | 1.1236 | 0.8678 |

| Wogonin | 0.0048 | n.d. |

| Norwogonin | 0.0074 | n.d. |

| Apigenin | 0.0013 | n.d. |

| Scutellarein | 0.0110 | n.d. |

| Chrysin | 0.0050 | n.d. |

| Oroxylin A | 0.0072 | 0.0012 |

| Compound | Retention Time (Minutes) | Quad 1 Mass | Quad 3 Mass | Depolarizing Potential (V) | Exit Potential (V) | Collision Energy (V) | Collision Cell Exit Potential (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baicalin | 2.82 | 447 | 271 | 100 | 15 | 30 | 10 |

| Wogonin | 4.8 | 285 | 270 | 100 | 10 | 30 | 5 |

| Wogonoside | 3.17 | 461 | 285 | 100 | 10 | 30 | 15 |

| Chrysin | 4.83 | 255 | 153 | 75 | 5 | 40 | 10 |

| Oroxylin A | 4.97 | 285 | 270 | 35 | 5 | 30 | 15 |

| Norwogonin | 3.65 | 271 | 169 | 75 | 15 | 40 | 10 |

| Apigenin | 3.5 | 271 | 153 | 50 | 5 | 40 | 20 |

| Scutellarein | 2.86 | 287 | 169 | 100 | 10 | 60 | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Long, D.M.; Martinez, J.; Soumyanath, A.; Kretzschmar, D. Scutellaria lateriflora Extract Supplementation Provides Resilience to Age-Related Phenotypes in Drosophila melanogaster. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010461

Long DM, Martinez J, Soumyanath A, Kretzschmar D. Scutellaria lateriflora Extract Supplementation Provides Resilience to Age-Related Phenotypes in Drosophila melanogaster. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010461

Chicago/Turabian StyleLong, Dani M., Jesus Martinez, Amala Soumyanath, and Doris Kretzschmar. 2026. "Scutellaria lateriflora Extract Supplementation Provides Resilience to Age-Related Phenotypes in Drosophila melanogaster" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010461

APA StyleLong, D. M., Martinez, J., Soumyanath, A., & Kretzschmar, D. (2026). Scutellaria lateriflora Extract Supplementation Provides Resilience to Age-Related Phenotypes in Drosophila melanogaster. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010461