Comparative Review of Cardioprotective Potential of Various Parts of Sambucus nigra L., Sambucus williamsii Hance, and Their Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Methods

3. Phytochemical Characteristic of Various Parts of S. nigra and S. williamsii

3.1. S. nigra

3.1.1. Fruits

3.1.2. Flowers

3.1.3. Leaves

3.1.4. Bark

3.2. S. williamsii

4. Cardioprotective Potential of Various Parts of S. nigra, S. williamsii, and Their Products (In Vitro and In Vivo Models)

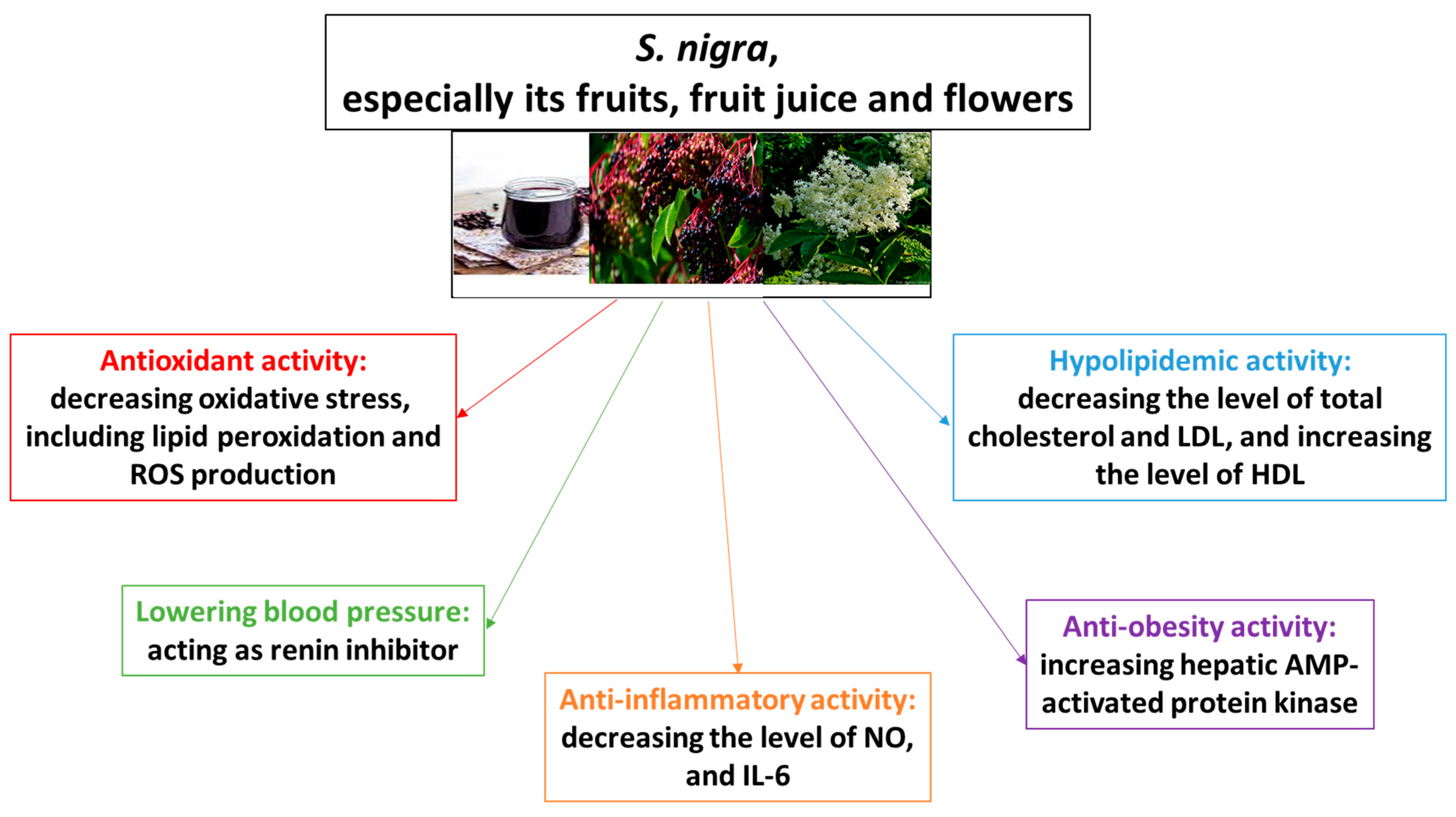

4.1. S. nigra

4.2. S. williamsii

5. Toxic Action and the Bioavailability of Bioactive Compounds

6. Concussions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Młynarczyk, K.; Walkowiak-Tomczak, D.; Łysiak, G.P. Bioactive properties of Sambucus nigra L. as a functional ingredient for food and pharmaceutical industry. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 40, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Młynarczyk, K.; Walkowiak-Tomczak, D. The effect of technological treatments and origin of raw material on the anti-oxidative activity and physicochemical properties of elderberry juice. Nauka Przyr. Technol. 2017, 11, 385–395. [Google Scholar]

- Młynarczyk, K.; Walkowiak-Tomczak, D. Evaluation of bioactive properties of selected elderberry products. Przem. Spoz. 2018, 8, 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Amini, E.; Nasrollahi, F.; Sattarian, A.; Isazadeh-Araei, M.; Habibi, M. Systematic and molecular biological study of Sambucus L. (Caprifoliaceae) in Iran. Thaiszia J. Bot. 2019, 29, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Xu, M.; Li, W. Antiviral phytomedicine elderberry (Sambucus) will be Inhibition of 2019-nCoV. Authorea Prepr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silalahi, M.; Wakhidah, A.Z. Sambucus javanica reinw. Ex Blume Viburnaceae. In Ethnobotany of the Mountain Regions of Southeast Asia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 40–41. [Google Scholar]

- Waswa, E.N.; Li, J.; Mkala, E.M.; Wanga, V.O.; Mutinda, E.S.; Nanjala, C.; Odago, W.O.; Katumo, D.M.; Gichua, M.K.; Gituru, R.W.; et al. Ethnobotany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and toxicology of the genus Sambucus L. (Viburnaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 292, 115102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, G.; Pasta, S.; Maggio, A.; La Mantia, T. Sambucus nigra L. (fam. Viburnaceaea) in Sicily: Distribution, ecology, traditional use and therapeutic properties. Plants 2023, 12, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, X.; Tang, Y.; Qu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, X.; Duan, X.; Song, X. Sambucus williamsii Hance: A comprehensive review of traditional uses, processing specifications, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, toxicology, and pharmacokinetics. J. Ethnopharm. 2024, 326, 117940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Meyer, G.; Anderson, A.T.; Lauber, K.M.; Gallucci, J.C.; Gao, G.; Kinghorn, A.D. Development of potential therapeutic agents from black elderberries (the fruits of Sambucus nigra L.). Molecules 2024, 29, 2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mans, D. The use of medicinal plants in Suriname. In Social Aspects of Health, Medicine and Disease in the Colonial and Post-Colonial Area; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 129–155. [Google Scholar]

- Tiboc Schnell, C.N.; Filip, G.A.; Decea, N.; Moldovan, R.; Opris, R.; Man, S.C.; Moldovan, B.; David, L.; Tabaran, F.; Olteanu, D.; et al. The impact of Sambucus nigra L. extract on inflammation, oxidative stress and tissue remodeling in a rat model of lipopolysaccharide-induced subacute rhinosinusitis. Inflammopharmacology 2021, 29, 753–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.L.; Byers, P.L.; Vincent, P.L.; Applequist, W.L.; Thomas, A.L. Medicinal attributes of American elderberry. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of North America; Mathe, A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 119–139. [Google Scholar]

- Agalar, H.G. Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.). Nonvitamin Nonmineral Nutr. Suppl. 2018, 2, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Athearn, K.; Jarnagin, D.; Sarkhosh, A.; Popeone, J.; Sargent, S. Elderberry and elderflower (Sambucus spp.): Markets, establishment costs, and potential returns. Edis 2021, 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najgebauer-Lejko, D.; Liszka, K.; Tabaszewska, M.; Domagała, J. Probiotic yoghurts with sea buckthorn, elderberry, and sloe fruit purees. Molecules 2021, 28, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Myracle, A.D. Development and evaluation of kefir products made with aronia or elderberry juice: Sensory and phytochemical characteristics. Int. Food Res. J. 2018, 25, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl, K.; Mitchell, A.E. Elderberry, an ancient remedy: A comprehensive study of the bioactive compounds in three Sambucus nigra L. subspecies. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. 2024, 15, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cais-Sokolinska, D.; Walkowiak-Tomczak, D. Consumer-perception, nutritional, and functional studies of a yogurt with restructured elderberry juice. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 1318–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazio, A.; Plastina, P.; Meijernik, J.; Witkamp, R.F.; Gabriele, B. Comparative analysis of seeds of wild fruits of Rubus and Sambucus species from Southern Italy: Fatty acids composition of the oil, total phenolic content, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of the methanolic extracts. Food Chem. 2013, 140, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Liu, D.L.; Wang, W.; Lv, X.M.; Li, W.; Shao, L.D.; Wang, W.J. Bioactive triterpenoids from Sambucus javanica Blume. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 2816–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.M.; Maltagliati, A.J. NRf2 at the heart of oxidative stress and cardiac protection. Physiol. Genom. 2018, 50, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetanovic, A. Sambucus ebulus L., antioxidants and potential in disease. Pathology 2020, 1, 321–333. [Google Scholar]

- Abdramanov, A.; Massanyi, P.; Sarsembayeva, N.; Usenbayev, A.; Alimov, J.; Tvrda, E. The in vitro effect of elderberry (Sambucus nigra) extract on the activity and oxidative profile of bovine spermatozoa. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2021, 1, 1319–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaffari, H.; Ataei-Pirkooh, A.; Mirghazanfari, S.M.; Barati, M. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection by Sambucus ebulus extract in vitro. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2021, 35, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neekhra, S.; Awasthi, H.; Singh, D.P. Beneficial effects of Sambucus nigra in chronic stress-induced neurobehavioral and biochemical perturbation in rodents. Pharmacogn. J. 2021, 13, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanlier, N.; Ejder, Z.B.; Irmak, E. Are the effects of bioactive components on human health a myth?: Black elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) from exotic fruits. Curr. Nutr. 2024, 13, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorakkattu, P.; Jain, S.; Sivapragasam, N.; Maurya, A.; Tiwari, S.; Dwivedy, A.K.; Koirala, P.; Nirmal, N. Edible berries-an update on nutritional composition and health benefits-part II. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2025, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waszkiewicz-Robak, B.; Biller, E. Health benefits of elderberry. Probl. Hig. Epidemiol. 2018, 99, 217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Veberic, R.; Jakopic, J.; Stampar, F.; Schmitzer, V. European elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) rich in sugars, organic acids, anthocyanins and selected polyphenols. Food Chem. 2009, 114, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaack, K. Aroma composition and sensory quality of fruit juices processed from cultivars of elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 227, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaack, K.; Christensen, L.P.; Hughes, M.; Eder, R. Relationship between sensory quality and volatile compounds of elderflower (Sambucus nigra L.) extracts. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2006, 223, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; He, X.Q.; Wu, D.T.; Li, H.B.; Feng, Y.B.; Zou, L.; Gan, R.Y. Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.): Bioactive compounds, health functions, and application. Agricult. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 4202–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.H. Study on Extraction and Activity of Active Components in Different Parts from Sambucus williamsii Hance. Master’s Thesis, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Finn, C.E. Anthocyanins and other polyphenolics in American elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) and European elderberry (S. nigra) cultivars. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2007, 87, 2665–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.G.; Vance, T.M.; Nam, T.G.; Kim, D.O.; Koo, S.I.; Chun, O.K. Contribution of anthocyanin composition to total antioxidant capacity of berries. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2015, 70, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.M.; Yoon, Y.; Yoom, H.; Park, H.M.; Song, S.; Yeum, K.J. Dietary anthocyanins against obesity an inflammation. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olas, B. Berry phenolic antioxidants—Implications for human health? Front. Pharm. 2018, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitzer, V.; Veberic, R.; Slatnar, A.; Stampar, F. Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) wine: A product reach in health promoting compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 10143–10146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.F.R.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Heleno, S.A.; Barros, L.; Calhelha, R.C.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Anthocyanin profile of elderberry juice: A natural-based bioactive colouring ingredient with potential food application. Molecules 2019, 24, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.G.; Avula, B.; Katragunta, K.; Ali, Z.; Chittiboyina, A.G.; Khan, I.A. Elderberry extracts: Characterization of the polyphenolic chemical composition, quality consistency, safety, adulteration, and attenuation of oxidative stress- and inflammation-induced health disorders. Molecules 2023, 28, 3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzic, M.; Majkic, T.; Beara, I.; Zengin, G.; Miljic, U.; Djurovic, S.; Mollica, A.; Radojkovic, M. Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) wine a novel potential functional food product. Food Biosci. 2022, 50, 102047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enaru, B.; Dretcanu, G.; Pop, T.D.; Stanila, A.; Diaconeasa, Z. Anthocyanins: Factors affecting their stability and degradation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvador, A.C.; Rocha, S.M.; Silvestre, A.J.D. Lipophilic phytochemicals from elderberries (Sambucus nigra L.): Influence of ripening, cultivar and season. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 71, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaloki-Dorko, L.; Legradi, F.; Abranko, L.; Steger-Mate, M. Effects of food processing technology on valuable compounds in elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) varieties. Acta Biol. Szeged. 2014, 58, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Estevinho, B.N.; Rocha, F. Edible films prepared with different biopolymers, containing polyphenols extracted from elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.), to protect food products and to improve food functionality. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2020, 13, 1742–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.P.; Kaack, K.; Frette, X.C. Selection of elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) genotypes best suited for the preparation of elderflower extracts rich in flavonoids and phenolic acids. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2008, 227, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onolbaatar, O.; Dashbaldan, S.; Paczkowski, C.; Szakiel, A. Fruit and fruit-derived products of selected Sambucus plants as a source of phytosterols and triterpenoids. Plants 2025, 14, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glensk, M.; Czapinska, E.; Wozniak, M.; Ceremuga, I.; Wlodarczzyk, M.; Terlecki, G.; Ziolkowskia, P.; Seweryn, E. Triterpenoid acids as important antiproliferative constituents of Europeaen elderberry fruits. Nutr. Cancer 2017, 69, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulic-Petkovsek, M.; Samoticha, J.; Eler, K.; Stampar, F.; Veberic, R. Traditional elderflower beverages: A rich source of phenolic compounds with high antioxidant activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 1477–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.H.; Zhang, Y.; Cooper, R.; Yao, X.S.; Wong, M.S. Phytochemicals and potential health effects of Sambucus williamsii Hance (Jiegumu). Chin. Med. 2016, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.H.; Lu, L.; Poon, C.C.W.; Chan, C.O.; Wang, L.J.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Zhou, L.P.; Cao, S.; Yu, W.X.; Wong, K.Y.; et al. The lignan-rich fraction from Sambucus williamsii Hance ameliorates dyslipidemia and insulin resistance and modulates gut microbiota composition in ovariectomized rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.M.; Wu, H. Chemical constituents of Sambucus L. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 32, 2063–2072. [Google Scholar]

- Balkan, I.A.; Akulke, A.Z.I.; Bagatur, Y.; Telci, D.; Goren, A.C.; Kirmizibekmez, H.; Yesilada, E. Sambulin A and B, non-glycosidic iridoids from Sambucus ebulus, exert significant in vitro anti-inflammatory activity in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages via inhibition of MAPKs’s phosphorylation. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 206, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appenteng, M.K.; Krueger, R.; Johnson, M.C.; Ingold, H.; Bell, R.; Thomas, A.L.; Greenlief, C.M. Cyanogenic glycocise analysis in American elderberry. Molecules 2021, 26, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olas, B. Cardioprotective potential of berries of Schizandra chinensis Turcz. (Baill.), their components and food products. Nutrients 2023, 15, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olas, B. New light on changes in the number and function of blood platelets stimulated by of cocoa and its products. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1366076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.D.; Luo, M.; Shang, A.; Mao, Q.Q.; Li, B.Y.; Gan, R.Y.; Li, H.B. Antioxidant food components for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases: Effects, mechanisms, and clinical studies. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6627355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Ling, W.; Guo, H.; Song, F.; Ye, Q.; Zou, T.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, F.; et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of purified dietary anthocyanin in adults with hypercholesterolemia: A randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013, 23, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olas, B. The multifunctionality of berries toward blood platelets and the role of berry phenolics in cardiovascular disorders. Platelets 2017, 28, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shunkai, H.; Yiting, X.; Shadrack, S.M.; Jianghao, Z.; Lingxiao, X.; Yezhi, W.; Fei, W.; Chongjiang, C.; Xiao, X.; Biao, Y. Lycium barbarum (goji berry): A comprehensive review of chemical composition, bioactive compounds, health-promoting activities, and applications in functional foods and beyond. Food Chem. 2025, 496, 146588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Kondo, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Ikeda, Y.; Meng, X.; Umemura, K. Inhibitory effects of total flavones of Hippophae rhamnoides L. on thrombosis in mouse femoral artery and in vitro platelet aggregation. Life Sci. 2003, 72, 2263–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C.; Slavin, M.; Frankenfeld, C.L. Systematic review of anthocyanins and markers of cardiovascular disease. Nutrients 2016, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzik, T.J.; Touyz, R.M. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and vascular aging in hypertension. Hypertension 2017, 70, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois-Deruy, E.; Peugnet, V.; Turkieh, A.; Pinet, F. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular stress in cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants 2000, 9, 864–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibel, A.; Lukinac, A.M.; Dambic, V.; Juric, J.; Selthofer-Relatic, K. Oxidative stress in ischemic heart disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longer. 2020, 2020, 6627144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Cheng, C.K.; Zhang, C.L.; Huang, Y. Interplay between oxidative stress, cyclooxygenase, and prostanoids in cardiovascular diseases. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2021, 34, 784–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, R.; Zhang, L.; Rocchetti, G.; Lucini, L.; Pateiro, M.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M. Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) as potential source of antioxidants. Characterization, optimization of extraction parameters and bioactive properties. Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przybylska-Balcerek, A.; Szablewski, T.; Szwajkowska-Michałek, L.; Świderek, D.; Cegielska-Radziejewska, R.; Krejpcio, Z.; Suchowilska, E.; Tomczyk, Ł.; Stuper-Szablewska, L. Sambucus nigra extracts—Natural antioxidants and antimicrobial compounds. Molecules 2021, 26, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duymus, H.G.; Goger, F.; Husnu Can Baser, K. In vitro antioxidant properties and anthocyanin compositions of elderberry extracts. Food Chem. 2014, 155, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espin, J.K.; Soler-Rivas, C.; Wichers, H.J.; Garcia-Viguera, C. Anthocyanin-based natural colorants: A new source of antiradical activity for foodstuff. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1588–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołodziej, B.; Drożdżal, K. Antioxidant properties of black elder flowers and berries harvested from the wild. Żywność Nauka Technol. Jakość 2011, 4, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoilova, I.; Wilker, M.; Stoyanova, A.; Krastanov, A.; Stanchev, V. Antioxidant activity of extract from elder flower (Sambucus nigra L.). Herba Pol. 2007, 53, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bidian, C.; Mitrea, D.R.; Tatomir, C.; Perde-Schrepler, M.; Lazar, C.; Chetan, I.; Bolfa, P.; David, L.; Clichici, S.; Filip, G.A.; et al. Vitis vinifera, L.; Sambucus nigra, L. extracts attenuate oxidative stress and inflammation in femoral ischemia. Farmacia 2021, 69, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldbauer, K.; Seringer, G.; Sykora, C.; Dirsch, V.M.; Zehl, M.; Kopp, B. Evaluation of apricot, bilberry, and elderberry pomace constituents and their potential to enhance the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity. Acs. Omega 2018, 3, 10545–10553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, P.; Jayasooriya, A.P.; Cheema, S.K. Fish oil induced hyperlipidemia and oxidative stress in BioF1B hamsters is attenuated by elderberry extract. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 37, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocoiu, M.; Badescu, M.; Badulescu, O.; Badescu, L. The beneficial effects on blood pressure, dysplipidemia and oxidative stress of Sambucus nigra extract associated with renin inhibitors. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 3063–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, N.; Norris, G.; Lee, S.G.; Chun, O.K.; Blesso, C.N. Anthocyanin-rich black elderberry extract improves markers of HDL function and reduces aortic cholesterol in hyperlipidemic mice. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 1278–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, C.L.; Norris, G.H.; Jiang, C.; Kry, J.; Vitols, A.; Garcia, C.; Park, Y.K.; Lee, J.Y.; Blesso, C.N. Long-term supplementation of black elderberries promotes hyperlipidemia, but reduces liver inflammation and improves HDL function and atherosclerotic plague stability in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1800404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauray, A.; Felgines, C.; Morand, C.; Mazur, A.; Scalbert, A.; Milenkovic, D. Nutrigenomic analysis of the protective effects of bilberry anthocyanins-rich extract in apo e-deficient mice. Genes. Nutr. 2010, 5, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, P.J.; Kroon, P.A.; Hollands, W.J.; Walls, R.; Jenkins, G.; Kay, C.D.; Cassidy, A. Cardiovascular disease risk biomarkers and liver and kidney function are not altered in postmenopausal women after ingesting an elderberry extract rich in anthocyanins for 12 weeks. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 2266–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murkovic, M.; Abuja, P.; Bergmann, A.; Zirngast, A.; Adam, U.; Winklhofer-Roob, B.; Toplak, H. Effects of elderberry juice on fasting and postprandial serum lipids and low-density lipoprotein oxidation in healthy volunteers: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 58, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nillsen, A.; Salo, I.; Plaza, M.; Bjorck, J. Effects of a mixed berry beverage on cognitive functions and cardiometabolic risk markers; A randomized cross-over study in healthy older adults. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudah, S.; DeLucia, B.; Osborn, L.J.; Markley, R.L.; Bobba, V.; Preston, S.M.; Thamidurai, T.; Nia, L.H.; Fulmer, C.G.; Sangwan, N.; et al. Gut microbial conversion of dietary elderberry extract to hydrocinnamic acid improves obesity-associated metabolic disorders. bioRxiv 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.F.; Yan, X.R.; Yan, G.Q. Extraction flavonoids from Sambucus williamsii Hance leaves and evaluation of antioxidant activities. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2016, 37, 242–247. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z.X.; Wu, J.; Pan, H.; Wang, X.Y. Study on scavenging DPPH free radical of ethanol extract from elderberry fruit in wudalianchi. Heilongjiang Sci. 2018, 9, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.J.; Liu, J.Y.; Li, Y.; You, L.X. Optimization of extraction process of total saponins from Sambucus williamsii Hance leaves and its antioxidant activity in mice. China Food Addit. 2022, 33, 44–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, H.; Chen, S.; Xu, X.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, W.; Liu, K.; Liu, K. Isolation of linoleic acid from Sambucus williamsii seed oil extracted by high pressure fluid and its antioxidant, antiglycemic, hypolipidemic activities. Int. J. Food Eng. 2015, 11, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, D.; Tasinov, O.; Kisielova-Kanewa, Y. Improved lipid profile and increased serum antioxidant capacity in healthy volunteers after Sambucus ebulus L. fruit infusion consumption. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 6, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, A.M.; Abdel-Wahab, Y.H.A.; Flatt, P.R. The traditional plant treatment, Sambucus nigra (elder), exhibits insulin-like and insulin-releasing actions in vitro. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senica, M.; Stampar, F.; Veberic, R.; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M. The higher the better? Differences in phenolics and cyanogenic glycosides in Sambucus nigra leaves, flowers and berries from different altitudes. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 2623–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senica, M.; Stampar, F.; Veberic, R.; Mikulic-Petkovsek, M. Processed elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) products. A beneficial or harmful food alternative? LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 72, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejero, J.; Jimenez, P.; Quinto, E.J.; Cordoba-Diaz, D.; Garrosa, M.; Cordoba-Diaz, M.; Gayoso, M.J.; Girbes, T. Elderberries: A source of ribosome-inactivating proteins with lectin activity. Molecules 2015, 20, 2364–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, P.; Tejero, J.; Cordoba-Diaz, D.; Girbes, T. Differential sensitivity of D-galactose-binding lectins from fruits of dwarf elder (Sambucus ebulus L.) to a stimulated gastric fluid. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 794–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Assessment Report on Sambucus nigra L., Flos (EMA/HMPC/611504/2016); Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC): London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/herbal-report/final-assessment-report-sambucus-nigra-l-flos-revision-1_en.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- European Medicines Agency. Assessment Report on Sambucus nigra L., Fructus (EMA/HMPC/44208/2012); Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC): London, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/herbal-report/final-assessment-report-sambucus-nigra-l-fructus_en.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Festa, J.; Singh, H.; Hussain, A.; da Boit, M. Elderberries as a potential supplement to improve vascular function in a SARS-CoV-2 environment. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, R.S.; Bode, F.R. A review of the antiviral properties of black elder (Sambucus nigra L.) products. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 533–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Santos, P.; Nogueira, A.; Rocha, C.M.R.; Wilson, C.P.; Teixeira, J.A.; Botelho, C. Sambucus nigra flower and berry extracts for food and therapeutic applications: Effect of gastrointestinal digestion on in vitro and in vivo bioactivity and toxicity. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 6762–6776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J. Bioavailability of anthocyanins. Drug Metab. Rev. 2014, 46, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, I.; Faria, A.; Calhau, C.; de Freitas, V.; Mateus, N. Bioavailability of anthocyanins and derivatives. J. Funct. Foods 2014, 7, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netzel, M.; Strass, G.; Herbst, M.; Dietrich, H.; Bitsch, R.; Bitsch, I.; Frank, T. The excretion and biological antioxidant activity of elderberry antioxidants in healthy humans. Food Res. Inter. 2005, 38, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hribar, U.; Poklar Ulrih, N. The metabolism of anthocyanins. Curr. Drug Metab. 2014, 15, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Tan, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, G.; Sun, J.; Ou, S.; Chen, W.; Bai, W. Metabolism of anthocyanins and consequent effects on the gut microbiota. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olas, B.; Urbanska, K.; Brys, M. Selected food colourants with antiplatelet activity as promising compounds for the prophylaxis and treatment of thrombosis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 141, 111437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coultate, T.; Blackburn, R.S. Food colorants: Their past, present and future. Color. Technol. 2018, 134, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdson, G.T.; Tang, P.; Giusti, M.M. Natural colorants: Food colorants from natural sources. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 8, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalt, W.; Blumberg, J.B.; McDonald, J.E.; Vinqvist-Tymchuk, M.R.; Fillmore, S.A.E.; Graf, B.A.; O’Leary, J.M.; Milbury, P.E. Identification of anthocyanins in the liver, eye, and brain of blueberry-fed pigs. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.L.; Han, C.X.; Yang, X.J.; Wang, M.C.; Yang, Q.E.; Bu, S.H. Study on chemical constituents and rat-killing activity of Sambucus williamsii. Acta Bot. Boreali. Occident. Sin. 2004, 24, 1523–1526. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.G.; Lv, H.; Zhou, Z.L. Volatile components and cytotoxicity of Sambucus williamsii seed oil. J. Univ. Jinan Sci. Technol. 2022, 36, 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, H. Pharmacokinetic of the Sambucus williamsii Hance of morrosidie. Master’s Thesis, Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine, Harbin, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Part of Plant | Chemical Compound | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic Compounds | Dietary Fiber | Unsaturated Fatty Acids | Phytosterols | Terpenoid Compounds | |

| S. nigra | |||||

| Flowers | + | − | − | + | + |

| Fruits | + | + | + | + | + |

| Leaves | − | − | − | − | − |

| Bark | − | − | − | + | + |

| S. williamsii | |||||

| Flowers | + | − | − | − | − |

| Fruits | + | − | − | − | − |

| Leaves | − | − | − | − | − |

| Bark | − | − | − | − | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Olas, B. Comparative Review of Cardioprotective Potential of Various Parts of Sambucus nigra L., Sambucus williamsii Hance, and Their Products. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010460

Olas B. Comparative Review of Cardioprotective Potential of Various Parts of Sambucus nigra L., Sambucus williamsii Hance, and Their Products. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010460

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlas, Beata. 2026. "Comparative Review of Cardioprotective Potential of Various Parts of Sambucus nigra L., Sambucus williamsii Hance, and Their Products" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010460

APA StyleOlas, B. (2026). Comparative Review of Cardioprotective Potential of Various Parts of Sambucus nigra L., Sambucus williamsii Hance, and Their Products. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010460