Molecular Interactions of Norfloxacin in Metal-Loaded Clay Suspensions-Effects on Degradation and Induced Toxicity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

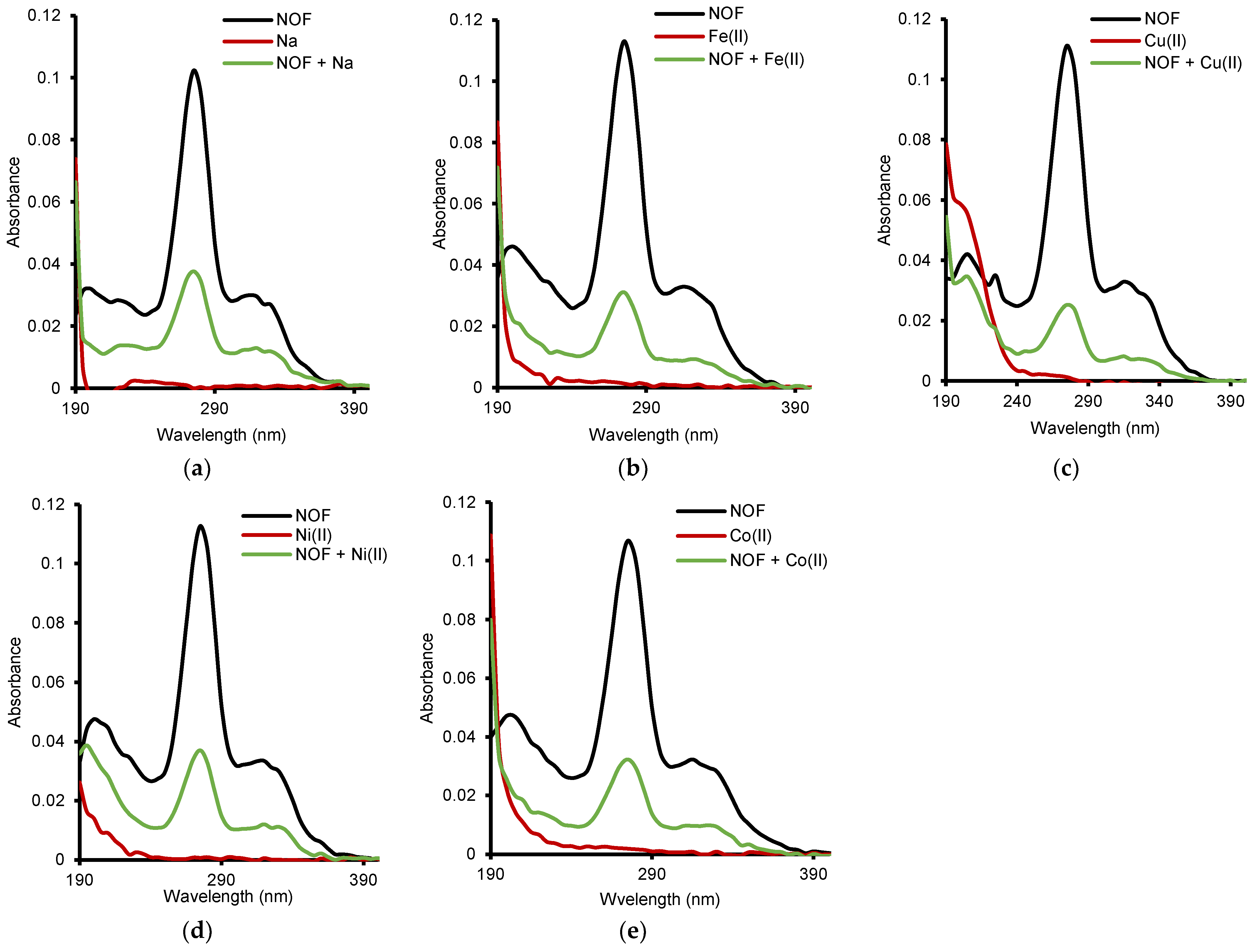

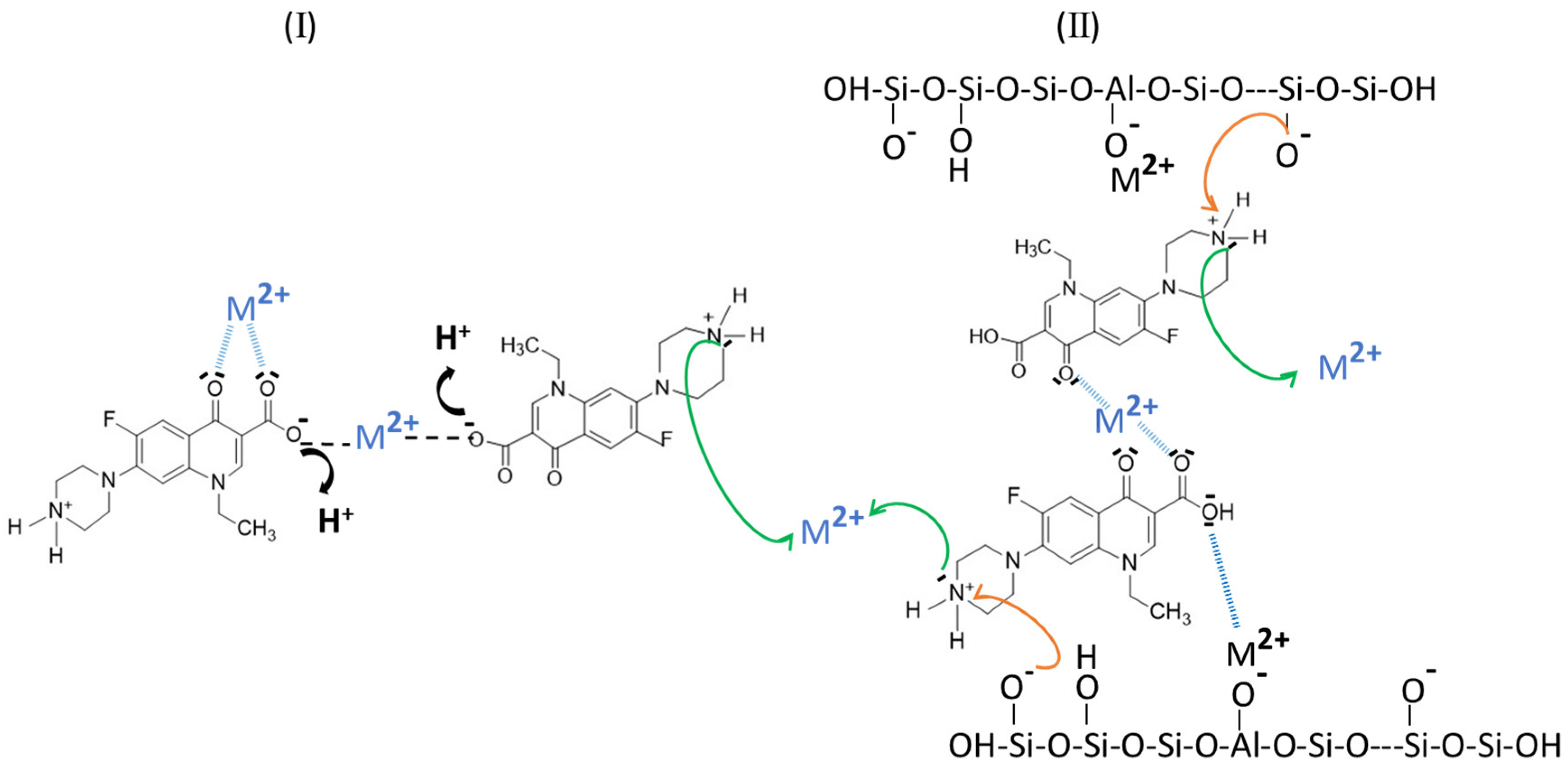

2.1. Metal Cation: NOF Interaction

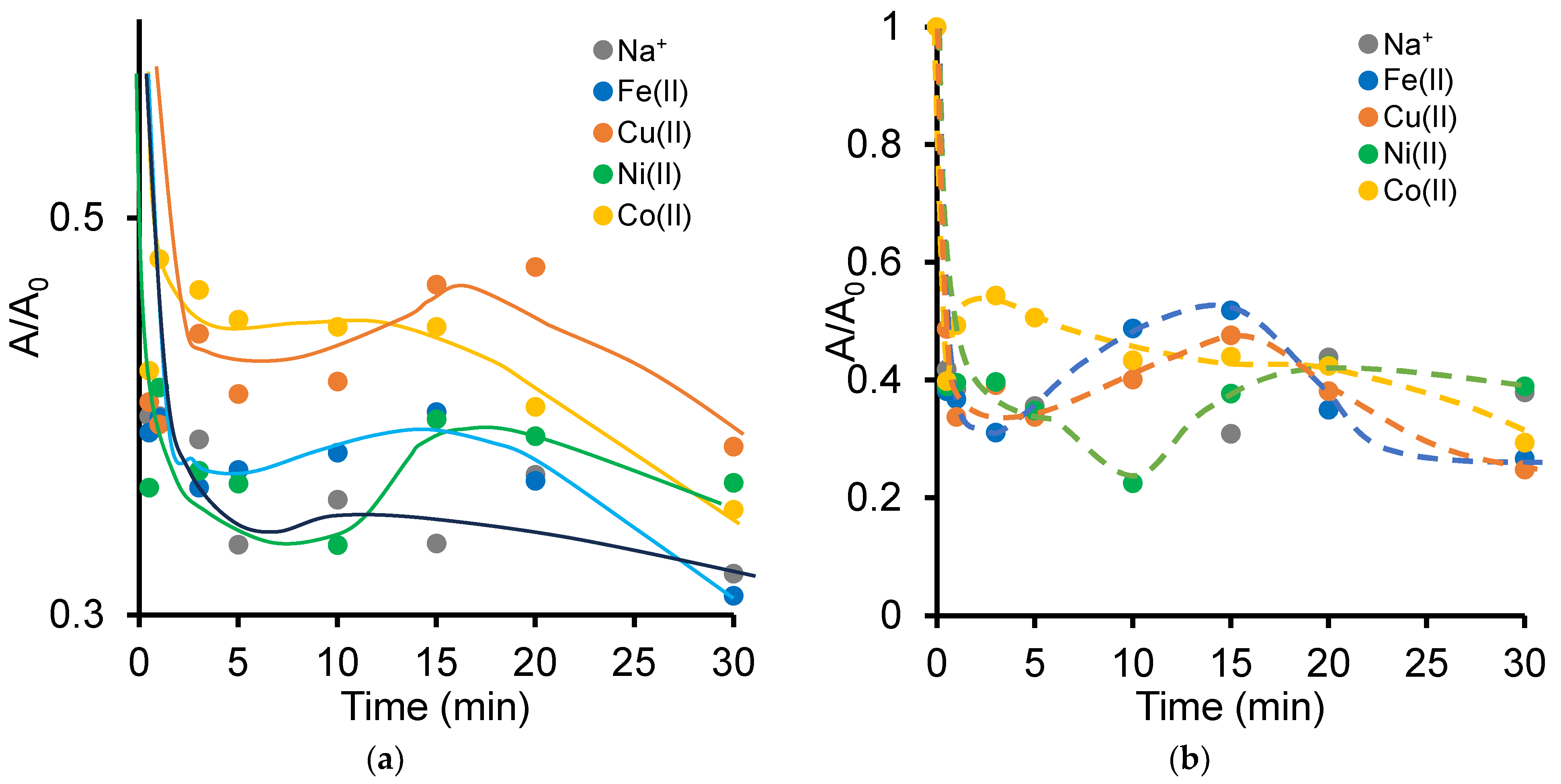

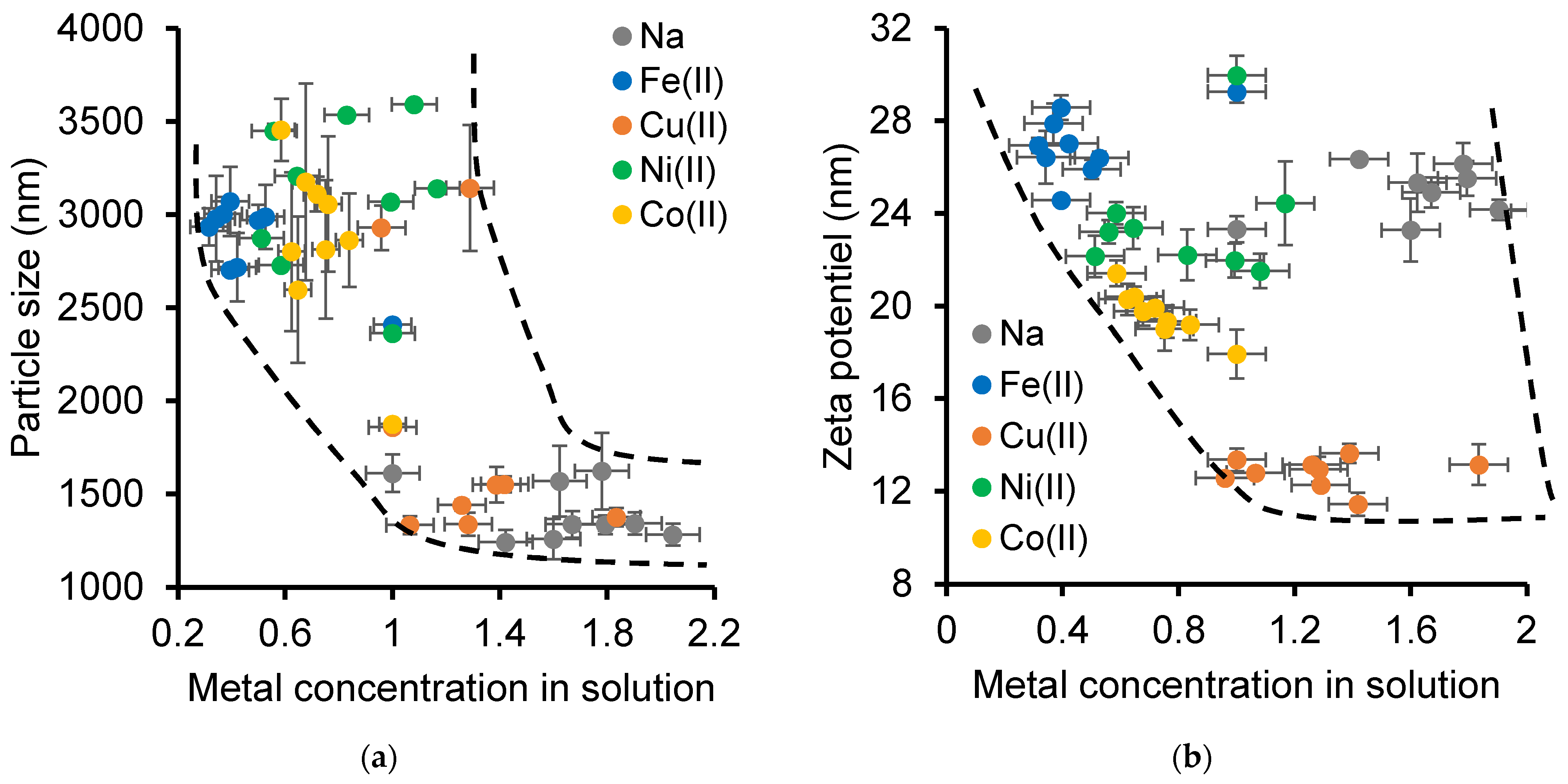

2.2. Effect of [NOF:Metal] Interaction on Clay Mineral Dispersion During Adsorption

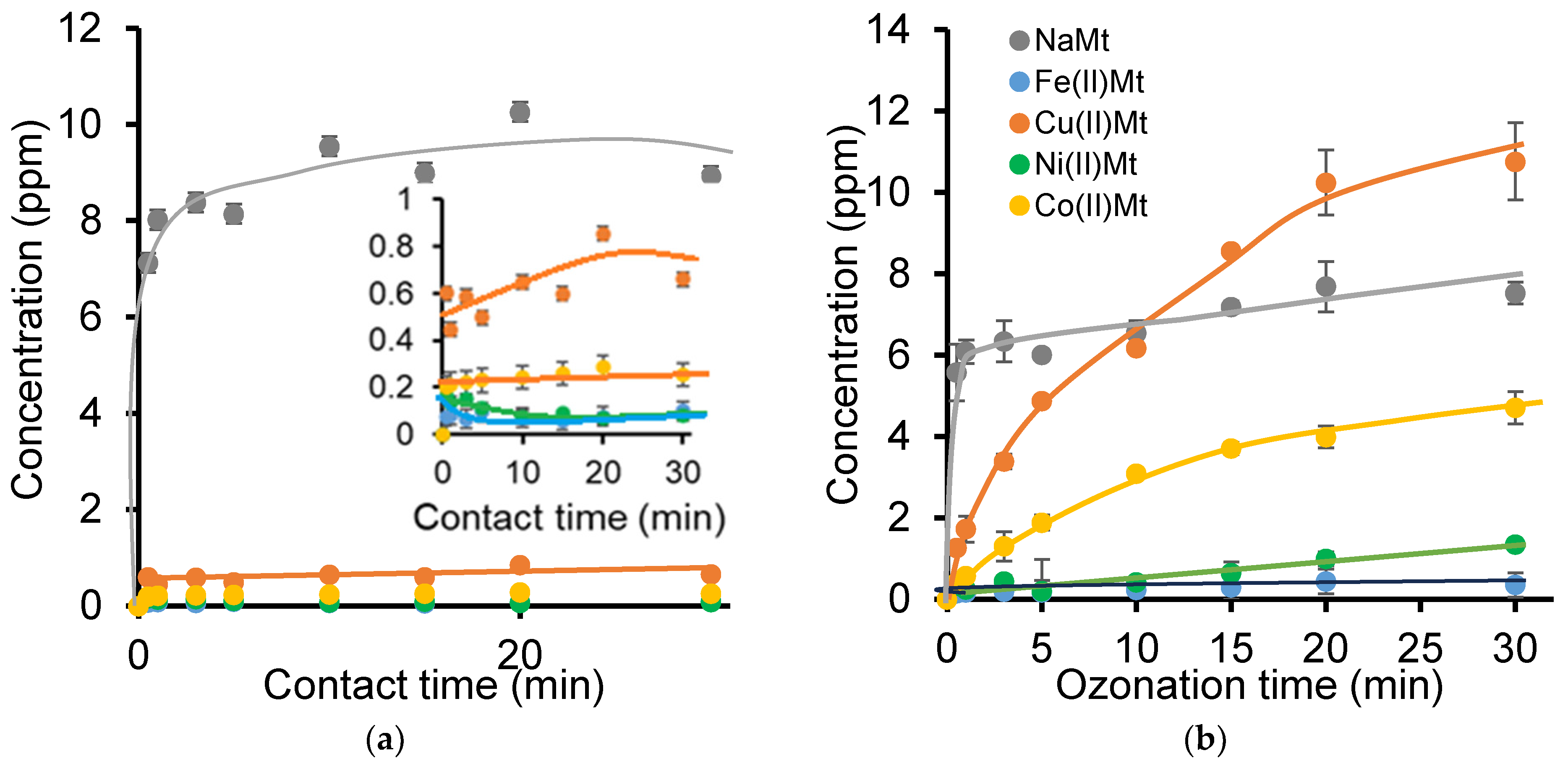

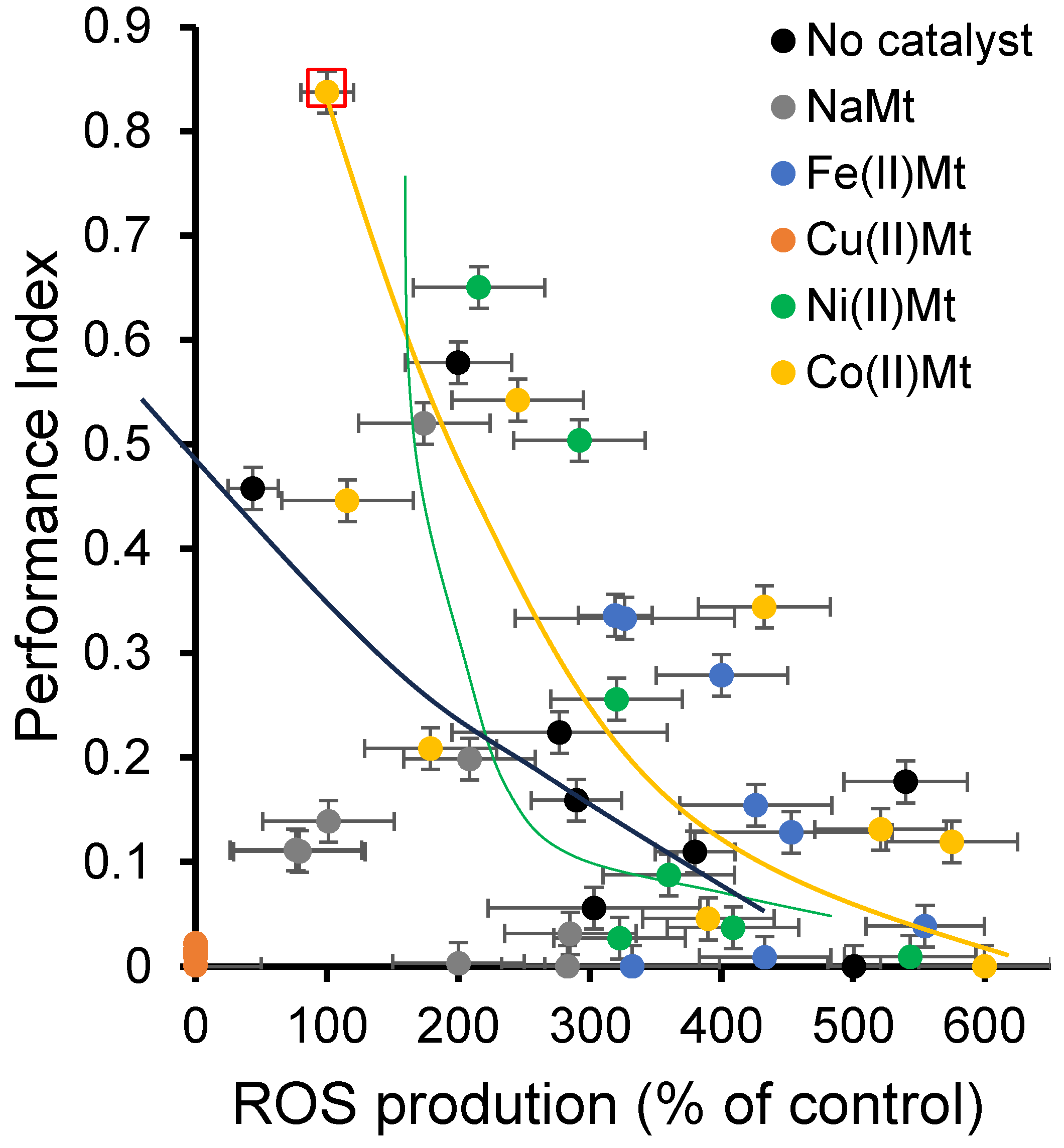

2.3. Clay Mineral Amount Effect on Ozonation and Toxicity

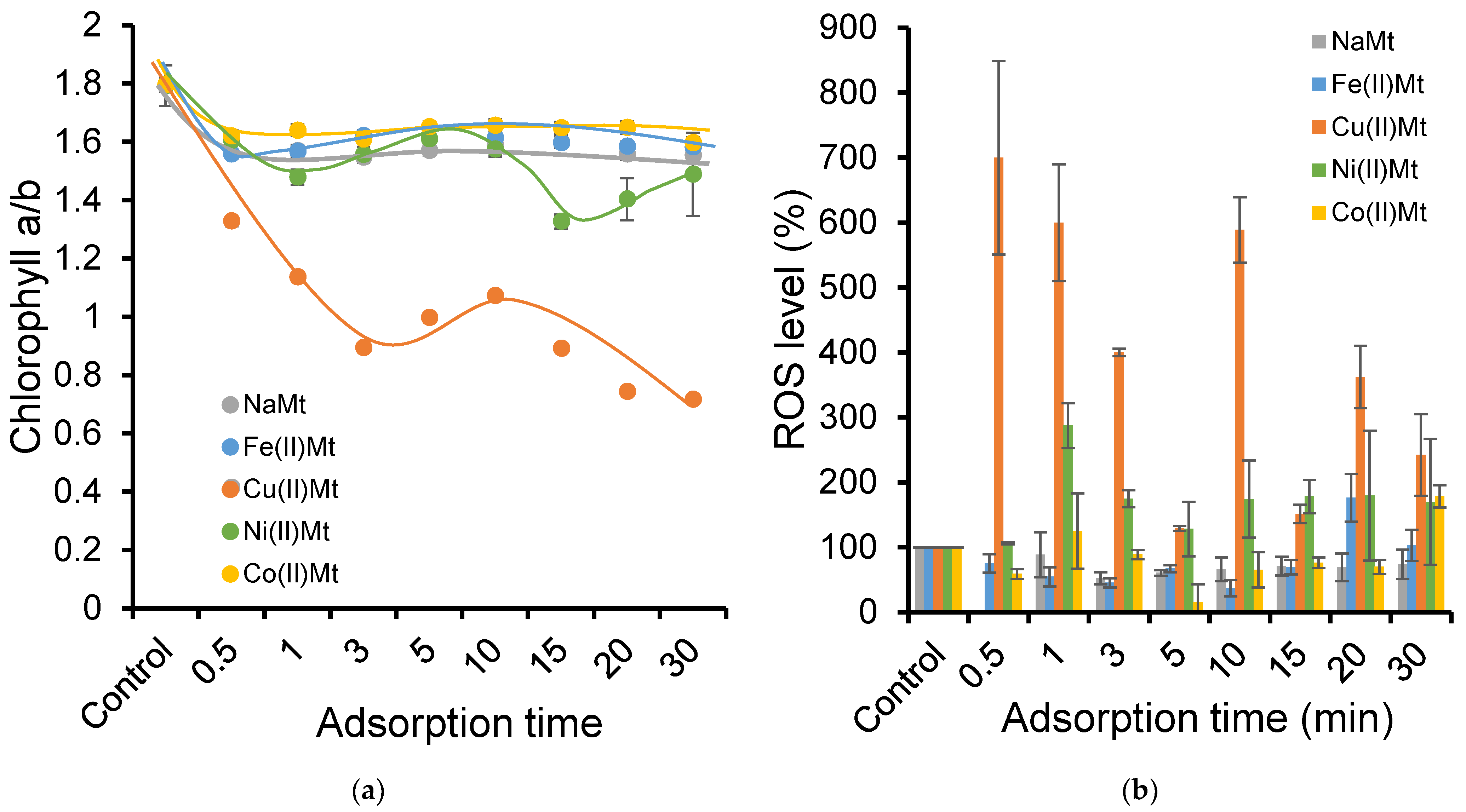

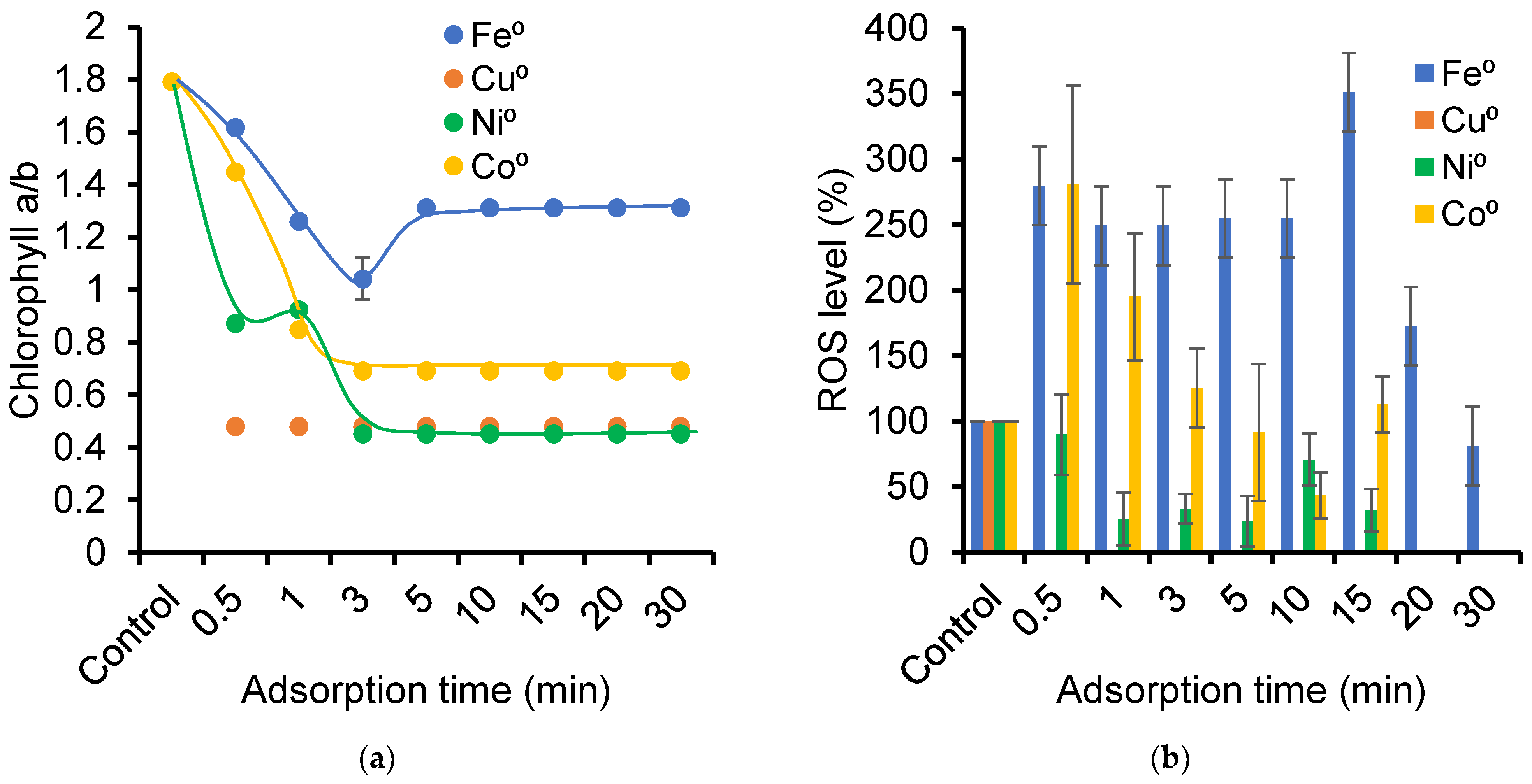

2.4. Ozonation Effect on Photosynthetic System

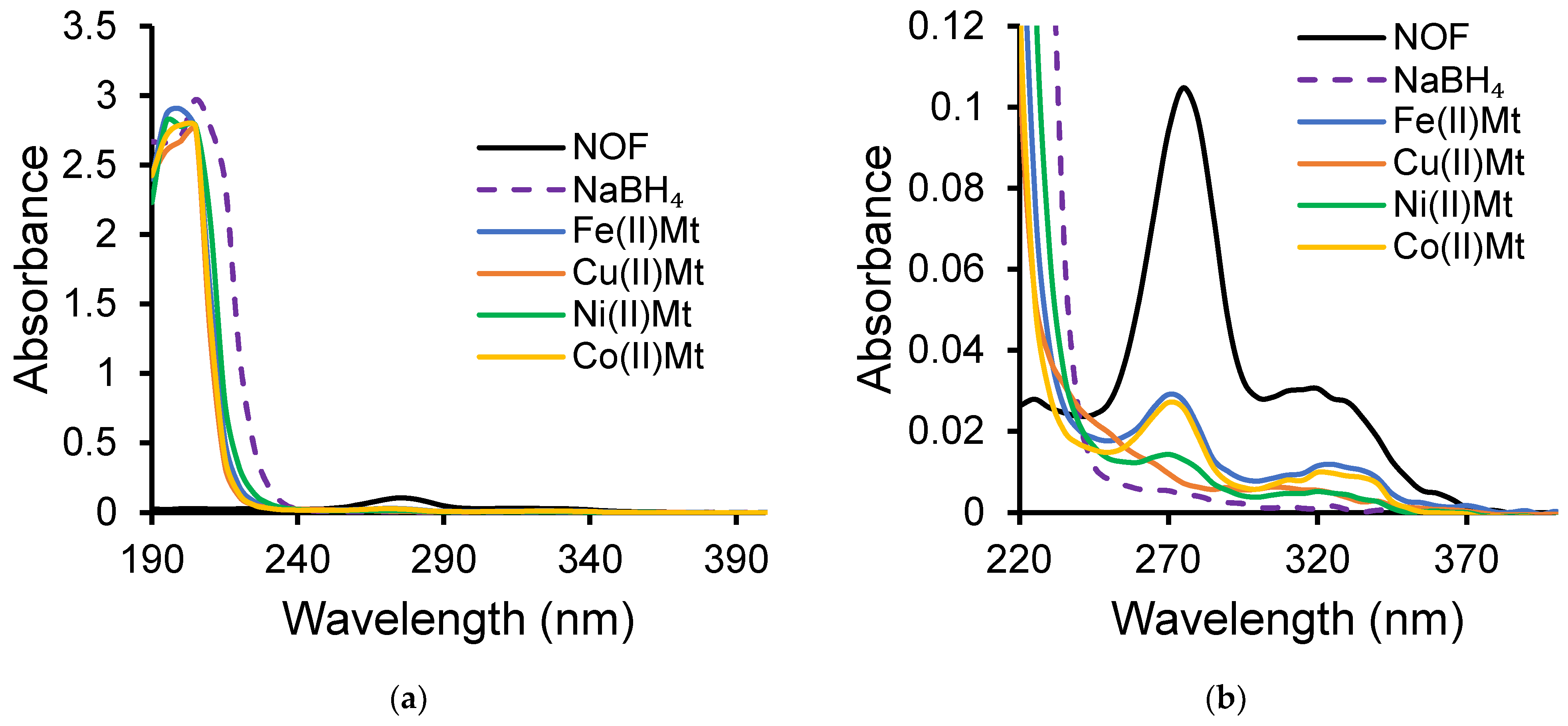

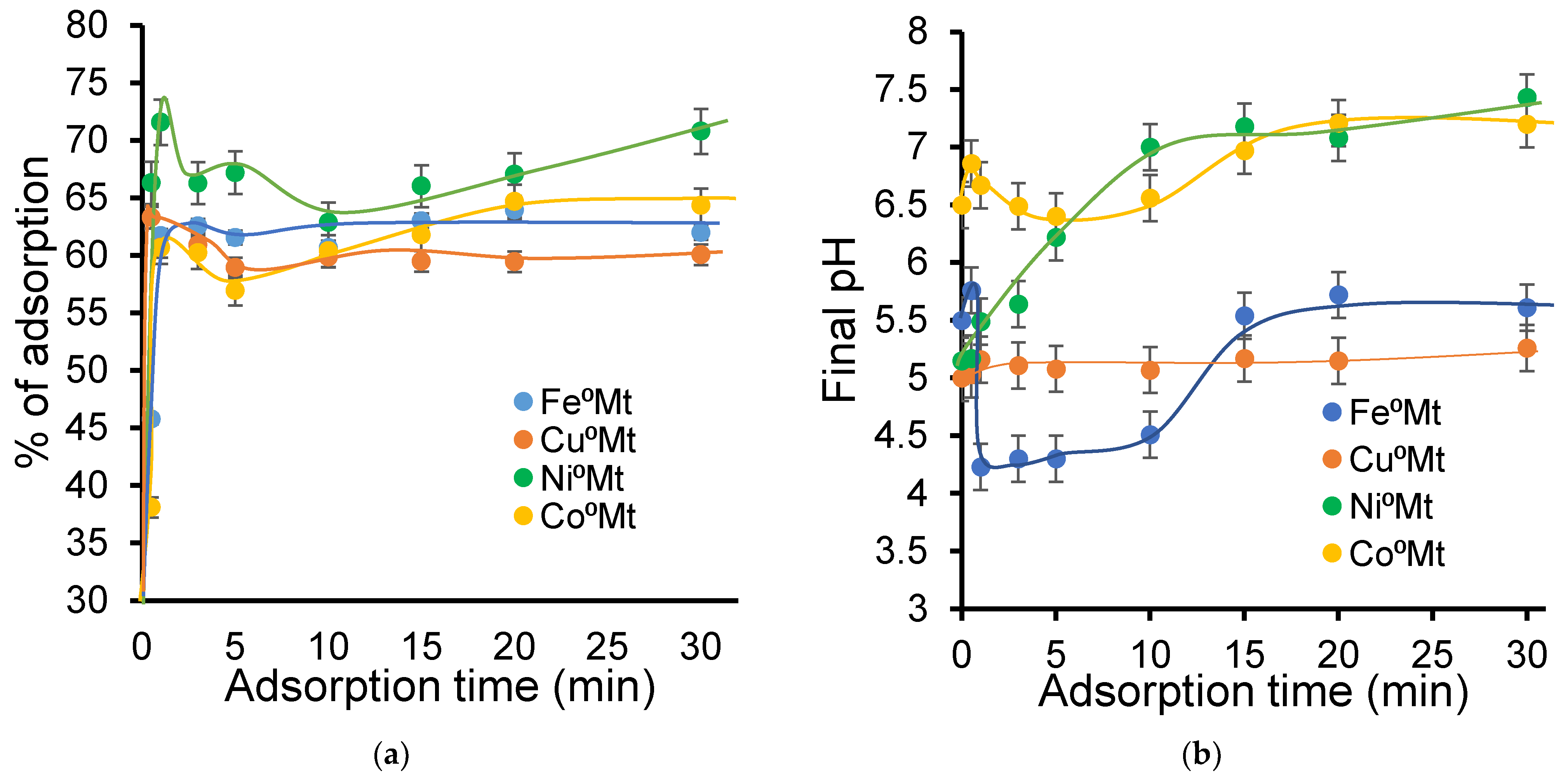

2.5. NOF Interaction with Clay-Supported Zero-Valent Metal

2.6. Toxicity of NOF Adsorbed on ZVM-Loaded Montmorillonite

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Chemicals and Stock Solutions

3.2. Preparation of Montmorillonite-Based Adsorbent/Catalysts

3.3. Metal-NOF Interaction Study

3.4. Adsorption Tests

3.5. Ozonation Tests

3.6. Toxicity Tests on Lemna minor

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hacıosmanoğlu, G.G.; Mejías, C.; Martín, J.; Santos, J.L.; Aparicio, I.; Alonso, E. Antibiotic adsorption by natural and modified clay minerals as designer adsorbents for wastewater treatment: A comprehensive review. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 317, 115397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalakova, P.; Cizmas, L.; McDonald, T.J.; Marsalek, B.; Feng, M.; Sharma, V.K. Occurrence and toxicity of antibiotics in the aquatic environment: A review. Chemosphere 2020, 251, 126351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, A.; Gauba, P. Harnessing Plants for Ciprofloxacin Pollution: A Green Approach. Defence 2025, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armelle Tchoumi Neree, A.; Noori, F.; Azzouz, A.; Costa, M.; Fairbrother, J.M.; Mateescu, M.A.; Chorfi, Y. Silver and Copper Nanoparticles Hosted by Carboxymethyl Cellulose Reduce the Infective Effects of Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli: F4 on Porcine Intestinal Enterocyte IPEC-J2. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Viezcas, J.; Castillo-Michel, H.; Servin, A.; Peralta-Videa, J.; Gardea-Torresdey, J. Spectroscopic verification of zinc absorption and distribution in the desert plant Prosopis juliflora-velutina (velvet mesquite) treated with ZnO nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 170, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miazek, K.; Iwanek, W.; Remacle, C.; Richel, A.; Goffin, D. Effect of metals, metalloids and metallic nanoparticles on microalgae growth and industrial product biosynthesis: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 23929–23969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Deng, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, C.; Ye, C.; Ling, X.; Li, X. Ascorbic acid enhanced ciprofloxacin degradation with nanoscale zero-valent copper activated molecular oxygen. Chemosphere 2021, 278, 130354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Song, Y.; Ling, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhan, X.; Xing, B. Fate of emerging antibiotics in soil-plant systems: A case on fluoroquinolones. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangla, D.; Sharma, A.; Ikram, S. Critical review on adsorptive removal of antibiotics: Present situation, challenges and future perspective. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 425, 127946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.-M.; Huang, H.-B.; Zhan, Z.-X.; Ye, Y.-Y.; Cheng, J.-L.; Xiang, L.; Li, Y.-W.; Cai, Q.-Y.; Xie, Y.; Mo, C.-H. Insights into the molecular network underlying phytotoxicity and phytoaccumulation of ciprofloxacin. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, X.; Cai, W.; Lin, S.; Chen, Z. Degradation mechanism of amoxicillin using clay supported nanoscale zero-valent iron. Appl. Clay Sci. 2017, 147, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, M.-C.; Spadini, L.; Brimo, K.; Martins, J.M. Speciation study in the sulfamethoxazole–copper–pH–soil system: Implications for retention prediction. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 481, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Fan, Z.; Song, P. Efficient degradation of Cu-Norfloxacin complexes in wastewater by electro-activated peroxymonosulfate coupled with electrocoagulation. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 70, 107140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, H.; Ma, J. Occurrence of trace elements and antibiotics in manure-based fertilizers from the Zhejiang Province of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 559, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, A.F.; Fabiani, M.; Lassalle, V.L.; Spetter, C.V.; Severini, M.F. Critical review of the characteristics, interactions, and toxicity of micro/nanomaterials pollutants in aquatic environments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 174, 113276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Yang, H.; Wen, T.; Wang, S.; Hu, B.; Wang, X. Removal of organic compounds by nanoscale zero-valent iron and its composites. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 792, 148546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, B.; Tanveer, M.; Rehman, A.; Cheema, S.A.; Fahad, S.; Rehman, S.; Sharma, A. Nickel; whether toxic or essential for plants and environment-A review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 132, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Vera, C.; Muñoz-Lira, D.; Aranda, M.; Toledo-Neira, C.; Salazar, R. Study of degradation of norfloxacin antibiotic and their intermediates by natural solar photolysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 41014–41027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Li, M.; Liu, B.; Meng, Q. Photochemical degradation kinetics and mechanisms of norfloxacin and oxytetracycline. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 8258–8265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Jiang, W.; Liang, B.; Han, J.; Cheng, H.; Haider, M.R.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Liu, S.; Wang, A. UV photolysis as an efficient pretreatment method for antibiotics decomposition and their antibacterial activity elimination. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 392, 122321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Zhang, P.; Song, H.; Ge, L.; Niu, J. Photochemical properties and toxicity of fluoroquinolone antibiotics impacted by complexation with metal ions in different pH solutions. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 150, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, Q.; Qiu, C.; Zheng, G.; Zhu, Q.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.; Shi, L.; Wang, H.; He, D.; Sadakane, M. Higher acidity promoted photodegradation of fluoroquinolone antibiotics under visible light by strong interaction with a niobium oxide based zeolitic octahedral metal oxide. Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 2023, 662, 119284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-J.; Li, Z.; Jiang, W.-T.; Jean, J.-S.; Liu, C.-C. Cation exchange interaction between antibiotic ciprofloxacin and montmorillonite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 183, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Z.-H.; Xu, X.-R.; Jiang, D.; Kong, L.-J.; Sun, Y.-X.; Hu, Y.-X.; Hao, Q.-W.; Chen, H. Bentonite-supported nanoscale zero-valent iron/persulfate system for the simultaneous removal of Cr(VI) and phenol from aqueous solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 302, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciğeroğlu, Z.; El Messaoudi, N.; Şenol, Z.M.; Başkan, G.; Georgin, J.; Gubernat, S. Clay-based nanomaterials and their adsorptive removal efficiency for dyes and antibiotics: A review. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 26, 100735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, D.; Bhattarai, A.; Chaudhary, N.K. Aquifer pollution by metal-antibiotic complexes: Origins, transport dynamics, and ecological impacts. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 288, 117390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roca Jalil, M.E.; Toschi, F.; Baschini, M.; Sapag, K. Silica pillared montmorillonites as possible adsorbents of antibiotics from water media. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca Jalil, M.E.; Baschini, M.; Sapag, K. Removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous solutions using pillared clays. Materials 2017, 10, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djidja, R.; Dewez, D.; Azzouz, A. Clay-catalyzed ozonation of Norfloxacin-Effects of metal cation and degradation rate on aqueous media toxicity towards Lemna minor. Chemosphere 2025, 372, 144088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djidja, R.; Dewez, D.; Azzouz, A. Norfloxacin Oxidative Degradation and Toxicity in Aqueous Media: Reciprocal Effects of Acidity Evolution on Metal Cations and Clay Catalyst Dispersion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Mandal, M.; Kundu, S.; Nath, S.; Pal, T. Bimetallic Pt–Ni nanoparticles can catalyze reduction of aromatic nitro compounds by sodium borohydride in aqueous solution. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2004, 268, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, N.; El Achari, A.; Campagne, C.; Vieillard, J.; Azzouz, A. Polyfunctional cotton fabrics with catalytic activity and antibacterial capacity. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 351, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, N.; El Achari, A.; Campagne, C.; Vieillard, J.; Azzouz, A. Copper oxide coated polyester fabrics with enhanced catalytic properties towards the reduction of 4-nitrophenol. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 10802–10813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, N.; El-Achari, A.; Campagne, C.; Vieillard, J.; Azzouz, A. Inorganic-organic-fabrics based polyester/cotton for catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1180, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, N.; Morshed, M.N.; Ahmida, E.A.; Nemeshwaree, B.; Christine, C.; Julien, V.; Olivier, T.; Azzouz, A. Development of new multifunctional filter based nonwovens for organics pollutants reduction and detoxification: High catalytic and antibacterial activities. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 356, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, N.; Vieillard, J.; Bargougui, R.; Couvrat, N.; Thoumire, O.; Morin, S.; Ladam, G.; Mofaddel, N.; Brun, N.; Azzouz, A.; et al. Entrapment and stabilization of iron nanoparticles within APTES modified graphene oxide sheets for catalytic activity improvement. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 771, 1090–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, N.; Vieillard, J.; Thebault, P.; Desriac, F.; Clamens, T.; Bargougui, R.; Couvrat, N.; Thoumire, O.; Brun, N.; Ladam, G.; et al. Silver nanoparticle embedded copper oxide as an efficient core-shell for the catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol and antibacterial activity improvement. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 9143–9155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, M.; Liu, H.; Ma, J.; Li, F. Modification of Pd–Fe nanoparticles for catalytic dechlorination of 2, 4-dichlorophenol. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 449, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldermann, A.; Kaufhold, S.; Dohrmann, R.; Baldermann, C.; Letofsky-Papst, I.; Dietzel, M. A novel nZVI–bentonite nanocomposite to remove trichloroethene (TCE) from solution. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 131018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Guo, J.; Kan, Z.; Jia, Y. Catalytic ozonation mechanisms of Norfloxacin using Cu–CuFe2O4. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bai, Z. Fe-based catalysts for heterogeneous catalytic ozonation of emerging contaminants in water and wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 312, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Temsah, Y.S.; Joner, E.J. Effects of nano-sized zero-valent iron (nZVI) on DDT degradation in soil and its toxicity to collembola and ostracods. Chemosphere 2013, 92, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ševců, A.; El-Temsah, Y.S.; Filip, J.; Joner, E.J.; Bobčíková, K.; Černík, M. Zero-valent iron particles for PCB degradation and an evaluation of their effects on bacteria, plants, and soil organisms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 21191–21202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Li, X.; Pan, Z.; Ma, S.; Li, L. Synthesis of MnOx/SBA-15 for Norfloxacin degradation by catalytic ozonation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 173, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzatahmadi, N.; Ayoko, G.A.; Millar, G.J.; Speight, R.; Yan, C.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Xi, Y. Clay-supported nanoscale zero-valent iron composite materials for the remediation of contaminated aqueous solutions: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 312, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, E.A.; Açıkel, Y.S.; Aşçı, Y. A full factorial design for the decolorization of real textile wastewater using iron-rich montmorillonite by sonocatalytic process. Chem. Eng. Process.-Process Intensif. 2025, 208, 110111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahmatkesh Anbarani, M.; Najafpoor, A.; Barikbin, B.; Bonyadi, Z. Adsorption of tetracycline on polyvinyl chloride microplastics in aqueous environments. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulen, B.; Demircivi, P. Adsorption properties of flouroquinolone type antibiotic ciprofloxacin into 2: 1 dioctahedral clay structure: Box-Behnken experimental design. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1206, 127659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, P.; Zhao, L.; Zou, W. Optimization adsorption of norfloxacin onto polydopamine microspheres from aqueous solution: Kinetic, equilibrium and adsorption mechanism studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 639, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Ziaullah; Islam, N.U.; Ali, M.; Khan, S. Metal complexes of fluoroquinolones with selected transition metals, their synthesis, characterizations, and therapeutic applications. Chem. Afr. 2024, 7, 4139–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cai, X.; Lang, X.; Qiao, X.; Li, X.; Chen, J. Insights into aquatic toxicities of the antibiotics oxytetracycline and ciprofloxacin in the presence of metal: Complexation versus mixture. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 166, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noori, F.; Megoura, M.; Labelle, M.-A.; Mateescu, M.A.; Azzouz, A. Synthesis of Metal-Loaded Carboxylated Biopolymers with Antibacterial Activity through Metal Subnanoparticle Incorporation. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, S.; Chakraborti, C.K.; Behera, P.K.; Mishra, S. FTIR and Raman spectroscopic investigations of a norfloxacin/carbopol934 polymerie suspension. J. Young Pharm. 2012, 4, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refat, M.S. Synthesis and characterization of norfloxacin-transition metal complexes (group 11, IB): Spectroscopic, thermal, kinetic measurements and biological activity. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2007, 68, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuprys, A.; Pulicharla, R.; Brar, S.K.; Drogui, P.; Verma, M.; Surampalli, R.Y. Fluoroquinolones metal complexation and its environmental impacts. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 376, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Yu, J.-Y.; Gong, B.; Zhao, S.; Sun, X.-M.; Wang, S.-G.; Song, C. Cu(II) inhibits the photolysis via complexation-regulated excited state of enrofloxacin in seawater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Z.; Peng, A. Clay minerals-mediated removal of Norfloxacin and Norfloxin-resistant bacteria from water environments and associated mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 67024–67034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelaya Soule, M.E.; Flores, F.M.; Torres Sanchez, R.M.; Fernández, M.A. Norfloxacin adsorption on montmorillonite and carbon/montmorillonite hybrids: pH effects on the adsorption mechanism, and column assays. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2020, 56, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, D.; Roy, R.; Azzouz, A. Total removal of oxalic acid via synergistic parameter interaction in montmorillonite catalyzed ozonation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benghaffour, A.; Foka-Wembe, E.-N.; Dami, M.; Dewez, D.; Azzouz, A. Insight in natural media remediation through ecotoxicity correlation to clay catalyst selectivity in organic molecule ozonation. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 4366–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekkari, M.; Ouargli-Saker, R.; Boudissa, F.; Lachachi, A.K.; El Houda Sekkal, K.N.; Tayeb, R.; Boukoussa, B.; Azzouz, A. Silica-catalyzed ozonation of 17α-ethinyl-estradiol in aqueous media-to better understand the role of silica in soils. Chemosphere 2022, 298, 134312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larouk, S.; Ouargli, R.; Shahidi, D.; Olhund, L.; Shiao, T.C.; Chergui, N.; Sehili, T.; Roy, R.; Azzouz, A. Catalytic ozonation of Orange-G through highly interactive contributions of hematite and SBA-16–To better understand azo-dye oxidation in nature. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 1648–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirilă, D.-C.; Boudissa, F.; Beltrao-Nuñes, A.-P.; Platon, N.; Didi, M.-A.; Nistor, I.-D.; Roy, R.; Azzouz, A. Organic dye ozonation catalyzed by chemically modified montmorillonite K10–Role of surface basicity and hydrophilic character. Ozone Sci. Eng. 2020, 42, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benghaffour, A.; Dewez, D.; Azzouz, A. Correlation of pesticide ecotoxicity with clay mineral dispersion effect on adsorption and ozonation—An approach through impact assessment on Lemna minor. Appl. Clay Sci. 2023, 241, 107001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzouz, A.; Rotar, D.; Zvolinski, A.; Miron, A. Food quality control through modeling and optimisation of the manufacturing process using 3k factorial design procedures. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Modelling and Simulation in Technical and Social Sciences (Organized by the International Association for Advancement of Modelling and Simulation (AMSE) and the University of Girona), Girona, Spain, 25–27 June 2002; pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bodo, R.; Ahmanache, K.; Hausler, R.; Azzouz, A. Optimized extraction of total proteic mass from water hyacinth dry leaves. J. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2004, 3, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaad, E.; Azzouz, A.; Nistor, D.; Ursu, A.V.; Sajin, T.; Miron, D.N.; Monette, F.; Niquette, P.; Hausler, R. Metal removal through synergic coagulation–flocculation using an optimized chitosan–montmorillonite system. Appl. Clay Sci. 2007, 37, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitriu, E.; Lutic, D.; Hulea, V.; Dorohoi, D.; Azzouz, A.; Colnay, E.; Kappenstein, C. Synthesis optimization of chabasite-like SAPO-47 in the presence of sec-butylamine. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 1999, 31, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Siedlewicz, G.; Pazdro, K. The toxic effects of antibiotics on freshwater and marine photosynthetic microorganisms: State of the art. Plants 2021, 10, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aristilde, L.; Melis, A.; Sposito, G. Inhibition of photosynthesis by a fluoroquinolone antibiotic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1444–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Sohni, S.; Akhtar, K.; Bakhsh, E.M.; Nawaz, T.; Khan, S.B. Lignocellulose biomatrix zero-valent cobalt nanoparticles: A dip-catalyst for organic pollutants degradation. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 198, 116694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekewi, M.; Darwish, A.; Amin, M.; Eshaq, G.; Bourazan, H. Copper nanoparticles supported onto montmorillonite clays as efficient catalyst for methylene blue dye degradation. Egypt. J. Pet. 2016, 25, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; He, Q.; Yang, D.; Sun, Y.; Xie, H.; Chen, Y. Efficient degradation of ciprofloxacin in water using nZVI/g-C3N4 enhanced dielectric barrier discharge plasma process. Environ. Res. 2025, 268, 120833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Ai, Z.; Zhang, L. Total aerobic destruction of azo contaminants with nanoscale zero-valent copper at neutral pH: Promotion effect of in-situ generated carbon center radicals. Water Res. 2014, 66, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, P.V.F.; de Oliveira, A.F.; da Silva, A.A.; Lopes, R.P. Environmental remediation processes by zero valence copper: Reaction mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 14883–14903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, P.V.F.d.; Oliveira, A.F.d.; Silva, A.A.d.; Vaz, B.G.; Lopes, R.P. Study of ciprofloxacin degradation by zero-valent copper nanoparticles. Chem. Pap. 2019, 73, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; He, C.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Du, G. Advancements in removing common antibiotics from wastewater using nano zero valent iron. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 26272–26291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noori, F.; Neree, A.T.; Megoura, M.; Mateescu, M.A.; Azzouz, A. Insights into the metal retention role in the antibacterial behavior of montmorillonite and cellulose tissue-supported copper and silver nanoparticles. Rsc Adv. 2021, 11, 24156–24171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouazizi, N.; Barrimo, D.; Nousir, S.; Slama, R.B.; Roy, R.; Azzouz, A. Montmorillonite-supported Pd0, Fe0, Cu0 and Ag0 nanoparticles: Properties and affinity towards CO2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 402, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jmii, S.; Dewez, D. Toxic responses of palladium accumulation in duckweed (Lemna minor): Determination of biomarkers. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 1630–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strasser, R.J.; Tsimilli-Michael, M.; Srivastava, A. Analysis of the chlorophyll a fluorescence transient. In Chlorophyll a Fluorescence: A Signature of Photosynthesis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 321–362. [Google Scholar]

- Stirbet, A. On the relation between the Kautsky effect (chlorophyll a fluorescence induction) and photosystem II: Basics and applications of the OJIP fluorescence transient. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2011, 104, 236–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Djidja, R.; Dewez, D.; Azzouz, A. Molecular Interactions of Norfloxacin in Metal-Loaded Clay Suspensions-Effects on Degradation and Induced Toxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010459

Djidja R, Dewez D, Azzouz A. Molecular Interactions of Norfloxacin in Metal-Loaded Clay Suspensions-Effects on Degradation and Induced Toxicity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):459. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010459

Chicago/Turabian StyleDjidja, Roumaissa, David Dewez, and Abdelkrim Azzouz. 2026. "Molecular Interactions of Norfloxacin in Metal-Loaded Clay Suspensions-Effects on Degradation and Induced Toxicity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010459

APA StyleDjidja, R., Dewez, D., & Azzouz, A. (2026). Molecular Interactions of Norfloxacin in Metal-Loaded Clay Suspensions-Effects on Degradation and Induced Toxicity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010459