Mitigating Hydroxychloroquine-Induced Oxidative Liver Damage: The Roles of Adenosine Triphosphate, Liv-52, and Their Combination in Rats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Biochemical Findings

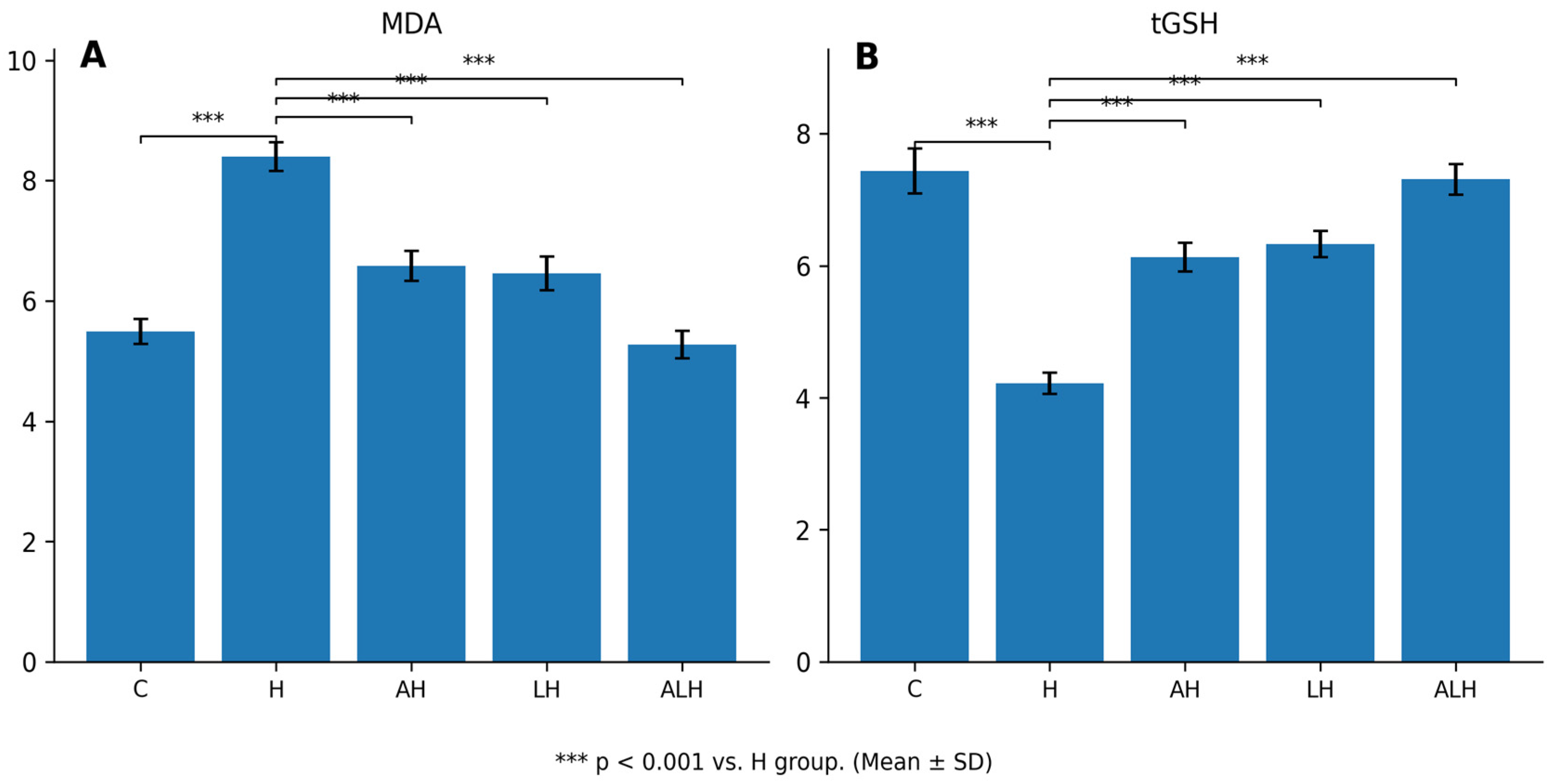

2.1.1. The Outcomes of the MDA and tGSH Assays in Liver Tissue

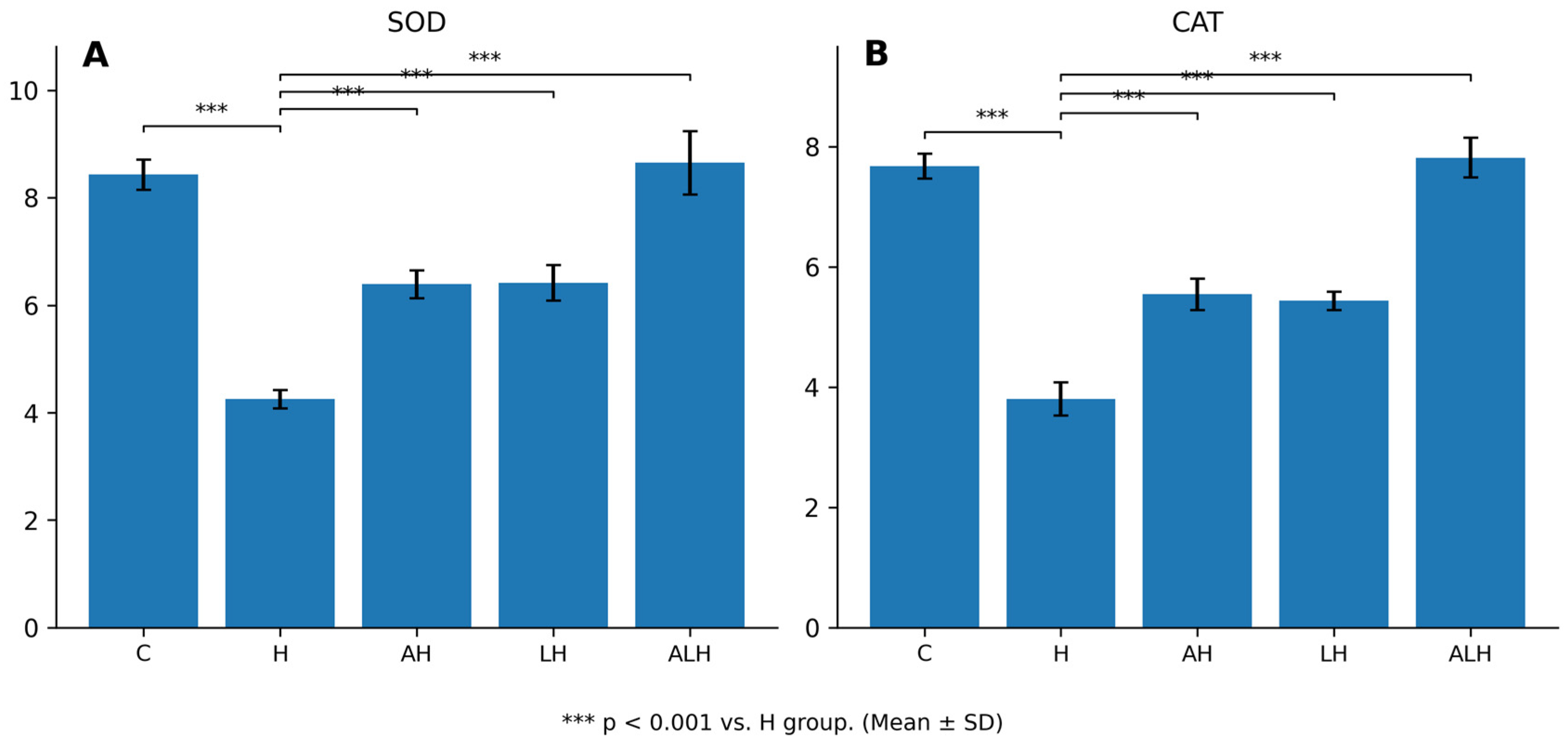

2.1.2. The Outcomes of the SOD and CAT Assays in Liver Tissue

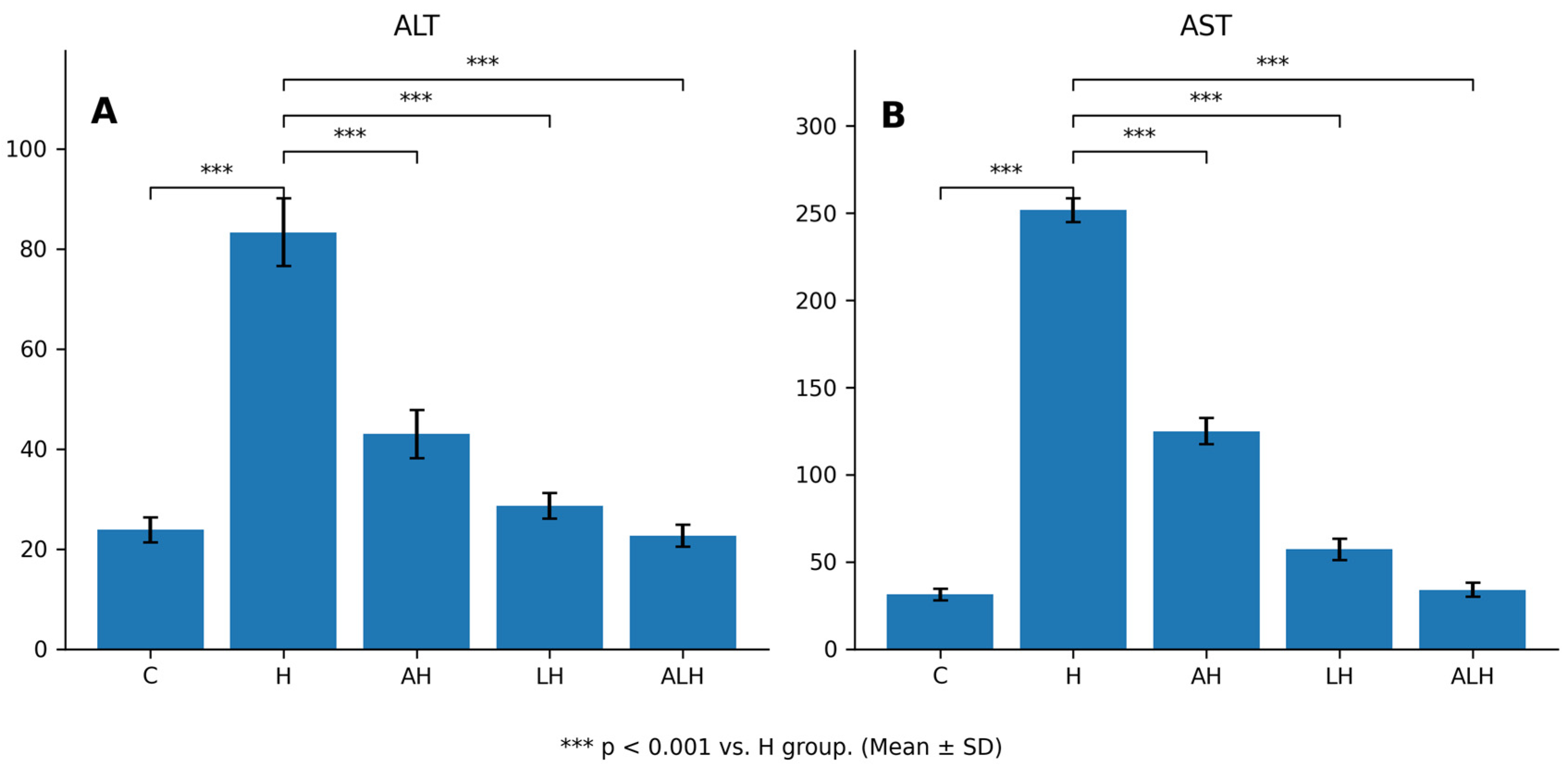

2.1.3. The Outcomes of the Blood Serum ALT and AST Assays

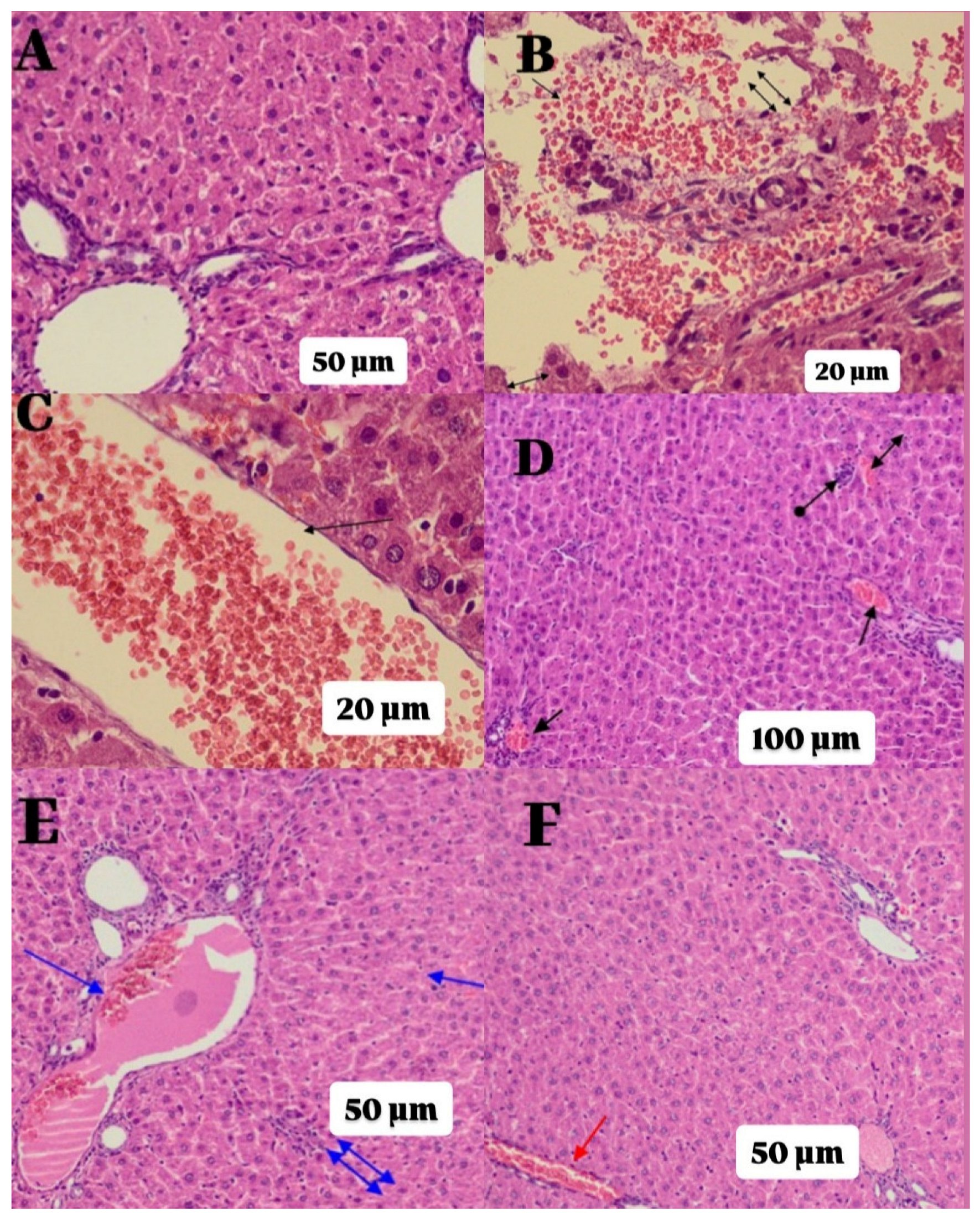

2.2. Histopathological Findings

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Chemicals

4.3. Experimental Design and Grouping

4.3.1. Experimental Design

4.3.2. Experimental Groups

4.4. Experiment Procedure

4.5. Biochemical Analysis

4.5.1. Preparation of Samples

4.5.2. Determination of MDA, tGSH, SOD, CAT and Protein in Liver Tissue

4.5.3. Determination of Blood Serum ALT and AST

4.6. Histopathological Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCQ | Hydroxychloroquine |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| tGSH | Total Glutathione |

| SOD | Superoxid Dismutase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| LPO | Lipid Peroxidation |

References

- Bansal, P.; Goyal, A.; Cusick, A.; Lahan, S.; Dhaliwal, H.S.; Bhyan, P.; Bhattad, P.B.; Aslam, F.; Ranka, S.; Dalia, T.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine: A comprehensive review and its controversial role in coronavirus disease 2019. Ann. Med. 2020, 53, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LiverTox. Hydroxychloroquine. In LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2012. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548738/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Stokkermans, T.J.; Falkowitz, D.M.; Trichonas, G. Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine Toxicity. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lei, Z.-N.; Wu, Z.-X.; Dong, S.; Yang, D.-H.; Zhang, L.; Ke, Z.; Zou, C.; Chen, Z.-S. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of malaria and repurposing in treating COVID-19. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 216, 107672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, R.; Wei, C.; Yang, Y.; Lin, J.; Huang, X. Hydroxychloroquine: A double-edged sword (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2025, 31, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainz-Gil, M.; Kolly, N.M.; Velasco-González, V.; Rello, Z.V.; Fernandez-Araque, A.M.; Fadrique, R.S.; Arias, L.H.M. Hydroxychloroquine safety in Covid-19 vs non-Covid-19 patients: Analysis of differences and potential interactions. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2022, 22, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falcão, M.B.; Cavalcanti, L.P.d.G.; Filho, N.M.F.; de Brito, C.A.A. Case Report: Hepatotoxicity Associated with the Use of Hydroxychloroquine in a Patient with COVID-19. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 102, 1214–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gişi, K.; İspiroğlu, M.; Kilinç, E. A Hydroxychloroquine-Related Acute Severe Liver Disease. Turk. Klin. J. Case Rep. 2022, 30, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Porta, A.; Bornstein, K.; Coye, A.; Montrief, T.; Long, B.; Parris, M.A. Acute chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine toxicity: A review for emergency clinicians. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 2209–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Samad, L.M.; Maklad, A.M.; Elkady, A.I.; Hassan, M.A. Unveiling the Mechanism of Sericin and Hydroxychloroquine in Suppressing Lung Oxidative Impairment and Early Carcinogenesis in Diethylnitrosamine-Induced Mice by Modulating PI3K/Akt/Nrf2/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 182, 117730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sheaff, R.J.; Hussaini, S.R. Chloroquine-Based Mitochondrial ATP Inhibitors. Molecules 2023, 28, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Grider, M.H. Physiology, Adenosine Triphosphate. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saquet, A.A.; Streif, J.; Bangerth, F. Changes in ATP, ADP and pyridine nucleotide levels related to the incidence of physiological disorders in ‘Conference’ pears and ‘Jonagold’ apples during controlled atmosphere storage. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2000, 75, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, J.; Qu, H.; Xue, S.; Duan, X.; Shi, J.; Prasad, N.K. ATP-regulation of antioxidant properties and phenolics in litchi fruit during browning and pathogen infection process. Food Chem. 2010, 118, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klouda, C.B.; Stone, W.L. Oxidative Stress, Proton Fluxes, and Chloroquine/Hydroxychloroquine Treatment for COVID-19. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, Y. Apoptosis and necrosis: Intracellular ATP level as a determinant for cell death modes. Cell Death Differ. 1997, 4, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivnitwar, S.K.; Gilada, I.; Rajkondawar, A.V.; Ojha, S.K.; Katiyar, S.; Arya, N.; Babu, U.V.; Kumawat, R. Safety and Effectiveness of Liv.52 DS in Patients With Varied Hepatic Disorders: An Open-Label, Multi-centre, Phase IV Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e60898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidyashankar, S.; Kumar, L.S.; Barooah, V.; Varma, R.S.; Nandakumar, K.S.; Patki; Liv, P.S. 52 up-regulates cellular antioxidants and increase glucose uptake to circumvent oleic acid induced hepatic steatosis in HepG2 cells. Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 1156–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainsford, K.D.; Parke, A.L.; Clifford-Rashotte, M.; Kean, W.F. Therapy and pharmacological properties of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and related diseases. Inflammopharmacology 2015, 23, 231–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, R. Systemic toxicity of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine: Prevalence, mechanisms, risk factors, prognostic and screening possibilities. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alruwaili, M.; Jarrar, B.; Jarrar, Q.; Alruwaili, M.; Goh, K.W.; Moshawih, S.; Ardianto, C.; Ming, L.C. Hydroxychloroquine Toxicity in the Vital Organs of the Body: In Vivo Study. Front. Biosci. 2023, 28, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galil, S.M.A. Hydroxychloroquine-induced toxic hepatitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report. Lupus 2014, 24, 638–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisi, K.; Ispiroglu, M.; Kilinc, E. A hydroxychloroquine-related acute liver failure case and review of the literature. J. Clin. Toxicol. 2021, 11, 1000004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, A.; Jurcut, C.; Chasset, F.; Felten, R.; Arnaud, L. Hydroxychloroquine in systemic lupus erythematosus: Overview of current knowledge. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2022, 14, 1759720X211073001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topak, D.; Gürbüz, K.; Doğar, F.; Bakır, E.; Gürbüz, P.; Kılınç, E.; Bilal, Ö.; Eken, A. Hydroxychloroquine induces oxidative stress and impairs fracture healing in rats. Jt. Dis. Relat. Surg. 2023, 34, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önaloğlu, Y.; Beytemür, O.; Saraç, E.Y.; Biçer, O.; Güleryüz, Y.; Güleç, M.A. The effects of hydroxychloroquine-induced oxidative stress on fracture healing in an experimental rat model. Jt. Dis. Relat. Surg. 2023, 35, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besaratinia, A.; Caliri, A.W.; Tommasi, S. Hydroxychloroquine induces oxidative DNA damage and mutation in mammalian cells. DNA Repair 2021, 106, 103180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, H.K.; Pereira, M.; Rajavelu, I.; Jayaraman, V.; Krishna, K.; Wang, T.; Bei, K.; Rajasekaran, J.J. Oxidative stress: Fundamentals and advances in quantification techniques. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1470458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Khzam, F.; Abou-Khzam, B. Physiological and Histological Studies on Moringa Effects Against Liver Toxicity Induced by Hydroxychloroquine in Rats. Libyan J. Ecol. Environ. Sci. Technol. (LJEEST) 2022, 4, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athari, S.Z.; Farajdokht, F.; Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Mohajeri, D.; Nourazar, M.A.; Mohaddes, G. Hydroxychloroquine attenuated motor impairment and oxidative stress in a rat 6-hydroxydopamine model of Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Neurosci. 2022, 133, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, R.J.; Althanoon, Z.A. Effects of Hydroxychloroquine on markers of oxidative stress and antioxidant reserve in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J. Adv. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2022, 12, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, M.; Mohamed, N. Potential Use of Quercetin as Protective Agent against Hydroxychloroquine Induced Cardiotoxicity. J. Biomed. Res. Environ. Sci. 2021, 2, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffmann, N.; da Penha, L.K.R.L.; Braga, D.V.; Ataíde, B.J.A.; Mendes, N.S.F.; de Sousa, L.P.; da Souza, G.S.; Passos, A.C.F.; Batista, E.J.O.; Herculano, A.M.; et al. Differential Effect of Antioxidants Glutathione and Vitamin C on the Hepatic Injuries Induced by Plasmodium berghei ANKA Infection. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9694508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva-Paz, M.; Morán, L.; López-Alcántara, N.; Freixo, C.; Andrade, R.J.; Lucena, M.I.; Cubero, F.J. Oxidative Stress in Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI): From Mechanisms to Biomarkers for Use in Clinical Practice. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.L.; Hardy, M.Y.; Edgington-Mitchell, L.E.; Ramarathinam, S.H.; Chung, S.Z.; Russell, A.K.; Currie, I.; Sleebs, B.E.; Purcell, A.W.; Tye-Din, J.A.; et al. Hydroxychloroquine inhibits the mitochondrial antioxidant system in activated T cells. iScience 2021, 24, 103509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamam, H.; Demir, H.; Aydin, M.; Demir, C. Determination of some Antioxidant Activities (Superoxide Dismutase, Catalase, Reduced Glutathione) and Oxidative Stress Level (Malondialdehyde Acid) in Cirrhotic Liver Patients. Middle Black Sea J. Heal. Sci. 2022, 8, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.A.; Ammar, O.A.; Amer, M.A.; Othman, A.I.; Zigheber, F.; El-Missiry, M.A. Hydroxychloroquine improves high-fat-diet-induced obesity and organ dysfunction via modulation of lipid level, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Egypt. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2023, 10, 368–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalas, M.A.; Chavez, L.; Leon, M.; Taweesedt, P.T.; Surani, S. Abnormal liver enzymes: A review for clinicians. World J. Hepatol. 2021, 13, 1688–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Pham, C.; Kaur, M.; Yip, K. Hydroxychloroquine-Induced Hepatotoxicity in Systemic Lupus Erythematous: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e81664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.M.; Varma, A.; Kumar, S.; Acharya, S.; Patil, R. Navigating Disease Management: A Comprehensive Review of the De Ritis Ratio in Clinical Medicine. Cureus 2024, 16, e64447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Jacobson, K.A. Purinergic Signaling in Liver Pathophysiology. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 718429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa, T.; Bellance, N.; Damm, A.; Bing, H.; Zhu, Z.; Handa, K.; Yovchev, M.I.; Sehgal, V.; Moss, T.J.; Oertel, M.; et al. A switch in the source of ATP production and a loss in capacity to perform glycolysis are hallmarks of hepatocyte failure in advance liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozer, M.; Ince, S.; Altuner, D.; Suleyman, Z.; Cicek, B.; Gulaboglu, M.; Mokhtare, B.; Gursul, C.; Suleyman, H. Protective Effect of Adenosine Triphosphate against 5-Fluorouracil-Induced Oxidative Ovarian Damage in vivo. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2023, 24, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbay, A.D.; Somuncu, A.M.; Cicek, I.; Yavuzer, B.; Bulut, S.; Huseynova, G.; Tastan, T.B.; Gulaboglu, M.; Suleyman, H. Effects of adenosine triphosphate and coenzyme Q10 on potential hydroxychloroquine-induced retinal damage in rats. Exp. Eye Res. 2025, 255, 110387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrakeeva, V.P. The Role of Extracellular ATP in the Regulation of Functional Cell Activity. Cell Tissue Biol. 2025, 19, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, N.; Lale, A.; Yazıcı, G.N.; Sunar, M.; Aktas, M.; Ozcicek, A.; Suleyman, B.; Ozcicek, F.; Suleyman, H. Ameliorative effects of Liv-52 on doxorubicin-induced oxidative damage in rat liver. Biotech. Histochem. 2022, 97, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantharia, C.; Kumar, M.; Jain, M.K.; Sharma, L.; Jain, L.; Desai, A. Hepatoprotective Effects of Liv.52 in Chronic Liver Disease Preclinical, Clinical, and Safety Evidence: A Review. Gastroenterol. Insights 2023, 14, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimen, O.; Eken, H.; Cimen, F.K.; Cekic, A.B.; Kurt, N.; Bilgin, A.O.; Suleyman, B.; Suleyman, H.; Mammadov, R.; Pehlivanoglu, K.; et al. The effect of Liv-52 on liver ischemia reperfusion damage in rats. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 21, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftel, S.; Ciftel, S.; Altuner, D.; Huseynova, G.; Yucel, N.; Mendil, A.S.; Sarigul, C.; Suleyman, H.; Bulut, S. Effects of adenosine triphosphate, thiamine pyrophosphate, melatonin, and liv-52 on subacute pyrazinamide proliferation hepatotoxicity in rats. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2025, 26, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament and Council. Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, L276, 33–79. [Google Scholar]

- du Sert, N.P.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, A.K.; Pheby, D.; Henehan, G.; Brown, R.; Sieving, P.; Sykora, P.; Marks, R.; Falsini, B.; Capodicasa, N.; Miertus, S.; et al. Ethical considerations regarding animal experimentation. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E255–E266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erhan, E.; Suleyman, Z.; Altuner, D.; Demir, O.; Gulaboglu, M.; Suleyman, H. Protective Effect of Adenosine Triphosphate Against Hydroxychloroquine Ototoxicity in Rats. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 38873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Góth, L. A simple method for determination of serum catalase activity and revision of reference range. Clin. Chim. Acta 1991, 196, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976, 72, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Groups | Histopathological Grading Data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenchymal Destruction | Hemorrhage | Edema | Vascular Dilatation/Congestion | |

| C | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) |

| H | 3.00 *** (2.00–3.00) | 3.00 *** (2.00–3.00) | 3.00 *** (3.00–3.00) | 3.00 *** (2.00–3.00) |

| AH | 2.00 * (1.00–2.00) | 2.00 * (1.00–3.00) | 1.50 * (1.00–2.00) | 2.00 * (1.00–2.00) |

| LH | 1.50 * (1.00–2.00) | 2.00 ** (2.00–3.00) | 1.50 * (1.00–2.00) | 1.50 * (1.00–2.00) |

| ALH | 1.00 +++ (0.00–1.00) | 1.00 +++ (0.00–2.00) | 1.00 +++ (0.00–1.00) | 1.00 +++ (0.00–2.00) |

| Group comparisons | p-values | |||

| C vs. H | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| C vs. AH | 0.030 | 0.037 | 0.067 | 0.058 |

| C vs. LH | 0.079 | 0.015 | 0.067 | 0.142 |

| C vs. ALH | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.588 |

| H vs. AH | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.358 | 0.588 |

| H vs. LH | 0.709 | 1.000 | 0.358 | 0.281 |

| H vs. ALH | 0.009 | 0.019 | 0.011 | 0.058 |

| AH vs. LH | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| AH vs. ALH | 0.709 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| LH vs. ALH | 1.000 | 0.603 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| K-W | 23.673 | 23.692 | 25.026 | 22.376 |

| df | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Asymptotic Sig. | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kandefer, M.Y.; Sezgin, E.T.; Suleyman, B.; Cimen, F.K.; Memiş, F.; Gulaboglu, M.; Suleyman, H. Mitigating Hydroxychloroquine-Induced Oxidative Liver Damage: The Roles of Adenosine Triphosphate, Liv-52, and Their Combination in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010421

Kandefer MY, Sezgin ET, Suleyman B, Cimen FK, Memiş F, Gulaboglu M, Suleyman H. Mitigating Hydroxychloroquine-Induced Oxidative Liver Damage: The Roles of Adenosine Triphosphate, Liv-52, and Their Combination in Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010421

Chicago/Turabian StyleKandefer, Meryem Yalvac, Esra Tuba Sezgin, Bahadir Suleyman, Ferda Keskin Cimen, Fulya Memiş, Mine Gulaboglu, and Halis Suleyman. 2026. "Mitigating Hydroxychloroquine-Induced Oxidative Liver Damage: The Roles of Adenosine Triphosphate, Liv-52, and Their Combination in Rats" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010421

APA StyleKandefer, M. Y., Sezgin, E. T., Suleyman, B., Cimen, F. K., Memiş, F., Gulaboglu, M., & Suleyman, H. (2026). Mitigating Hydroxychloroquine-Induced Oxidative Liver Damage: The Roles of Adenosine Triphosphate, Liv-52, and Their Combination in Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010421