From Ecological Threat to Bioactive Resource: The Nutraceutical Components of Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Determination of Proximate Composition

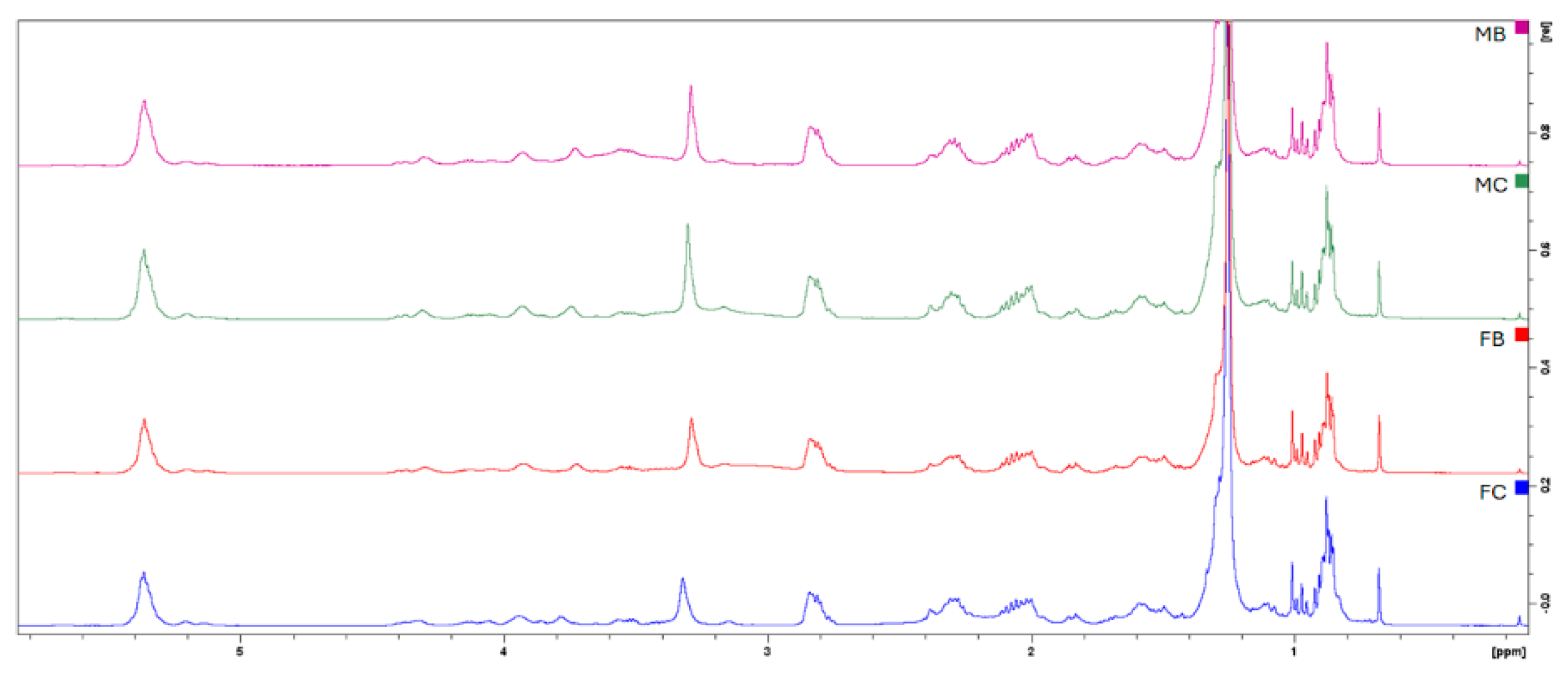

2.2. Analysis of the Lipidic Composition

2.3. Quantification of Astaxanthin in CS Meats

2.4. Analysis of Gastrointestinal Digestion Effects on Polyphenol Secondary Metabolites Composition, α-Glucosidase and ACE Inhibitory Activity

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Analysis and Water, Fats, and Protein Content

3.3. Gastrointestinal Digestion

3.4. Determination of Amino Acids

3.5. Quantification of Antioxidant Compounds and Antioxidant Activity

3.6. NMR Analysis

3.7. Determination of Fatty Acids

3.8. Quantification of Lipid Quality Indices

3.9. Astaxanthin Quantification

3.10. ACE Inhibitory Activity Assay

3.11. α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity Assay

3.12. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Union. Regulation (EU) No 1143/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 on the Prevention and Management of the Introduction and Spread of Invasive Alien Species. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, 317, 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Westphal, M.I.; Browne, M.; MacKinnon, K.; Noble, I. The Link between International Trade and the Global Distribution of Invasive Alien Species. Biol. Invasions 2008, 10, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchio, E.; Crotta, M.; Romeo, C.; Drewe, J.A.; Guitian, J.; Ferrari, N. Invasive Alien Species and Disease Risk: An Open Challenge in Public and Animal Health. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamassi, F.; Rjiba Bahri, W.; Mnari Bhouri, A.; Chaffai, A.; Soufi Kechaou, E.; Ghanem, R.; Ben Souissi, J. Biochemical Composition, Nutritional Value and Socio-Economic Impacts of the Invasive Crab Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, 1896 in Central Mediterranean Sea. Medit. Mar. Sci. 2022, 23, 650–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, G.; Lago, N.; Scirocco, T.; Lillo, O.A.; De Giorgi, R.; Doria, L.; Mancini, E.; Mancini, F.; Potenza, L.; Cilenti, L. Abundance, Size Structure, and Growth of the Invasive Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus in the Lesina Lagoon, Southern Adriatic Sea. Biology 2024, 13, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öztürk, B. Non-Indigenous Species in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-134775-1. [Google Scholar]

- GISD. Available online: https://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Nardelli, L.; Fucilli, V.; Pinto, H.; Elston, J.N.; Carignani, A.; Petrontino, A.; Bozzo, F.; Frem, M. Socio-Economic Impacts of the Recent Bio-Invasion of Callinectus Sapidus on Small-Scale Artisanal Fishing in Southern Italy and Portugal. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1466132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzurro, E.; Bonanomi, S.; Chiappi, M.; De Marco, R.; Luna, G.M.; Cella, M.; Guicciardi, S.; Tiralongo, F.; Bonifazi, A.; Strafella, P. Uncovering Unmet Demand and Key Insights for the Invasive Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus) Market before and after the Italian Outbreak: Implications for Policymakers and Industry Stakeholders. Marine Policy 2024, 167, 106295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglio, M.; Gavioli, A.; Turolla, E.; Lanzoni, M.; Castaldelli, G. The Costs of an Invasion: How the Blue Crab Impaired Ecosystem Services in the Most Productive Lagoon of Northwestern Adriatic. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 1007, 180952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto Ministeriale n. 587931 del 23 Ottobre 2023 Recante “Contrasto Alla Diffusione del Granchio blu “Callinectes Sapidus e Portunus Segnis”. Available online: https://www.masaf.gov.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeBLOB.php/L/IT/IDPagina/20517 (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Ortega-Jiménez, E.; Cuesta, J.A.; Laiz, I.; González-Ortegón, E. Diet of the Invasive Atlantic Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Decapoda, Portunidae) in the Guadalquivir Estuary (Spain). Estuaries Coasts 2024, 47, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiralongo, F.; Nota, A.; Pasquale, C.D.; Muccio, E.; Felici, A. Trophic Interactions of Callinectes Sapidus (Blue Crab) in Vendicari Nature Reserve (Central Mediterranean, Ionian Sea) and First Record of Penaeus Aztecus (Brown Shrimp). Diversity 2024, 16, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shauer, M.; Zangaro, F.; Specchia, V.; Pinna, M. Investigating Invasion Patterns of Callinectes Sapidus and the Relation with Research Effort and Climate Change in the Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 34967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severino-Rodrigues, E.; Musiello-Fernandes, J.; Mour, Á.A.S.; Branco, G.M.P.; Canéo, V.O.C. Fecundity, Reproductive Seasonality and Maturation Size of Callinectes Sapidus Females (Decapoda: Portunidae) in the Southeast Coast of Brazil. Rev. de Biol. Trop. 2013, 61, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glamuzina, L.; Pešić, A.; Marković, O.; Tomanić, J.; Pećarević, M.; Dobroslavić, T.; Brailo Šćepanović, M.; Conides, A.; Grđan, S. Population Structure of the Invasive Atlantic Blue Crab, Callinectes Sapidus on the Eastern Adriatic Coast (Croatia, Montenegro). Naše More 2023, 70, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, R.; Renda, G.; Ottaviani Aalmo, G.; Debeaufort, F.; Messina, C.M.; Santulli, A. Valorization of the Invasive Blue Crabs (Callinectes sapidus) in the Mediterranean: Nutritional Value, Bioactive Compounds and Sustainable By-Products Utilization. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Shaw, L.B.; Shi, J.; Lipcius, R.N. Impacts of Density-Dependent Predation, Cannibalism and Fishing in a Stage-Structured Population Model of the Blue Crab in Chesapeake Bay 2020. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaspie, C.; Seitz, R.; Lipcius, R. Are Predator-Prey Model Predictions Supported by Empirical Data? Evidence for a Storm-Driven Shift to an Alternative Stable State in a Crab-Clam System. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2020, 645, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipcius, R.; Stockhausen, W. Concurrent Decline of the Spawning Stock, Recruitment, Larval Abundance, and Size of the Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus in Chesapeake Bay. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2002, 226, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- From Invasive Species to Prized Export. Available online: https://www.fao.org/newsroom/story/From-invasive-species-to-prized-export/en (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Callinectes Sapidus—Introduced Species Fact Sheets. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/introsp/7847/en (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Fuso, A.; Paris, E.; Orsoni, N.; Bonzanini, F.; Larocca, S.; Caligiani, A. Chemical Composition of Blue Crabs From Adriatic Sea. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2025, 37, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükgülmez, A.; Çelik, M.; Yanar, Y.; Ersoy, B.; Çikrikçi, M. Proximate Composition and Mineral Contents of the Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus) Breast Meat, Claw Meat and Hepatopancreas. Int. J. Food Sci. Tech. 2006, 41, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramez, A.; Abd El-ghany, S. Nutritional Quality of Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus) Caught off the Mediterranean Water, Egypt. J. Environ. Sci. Mansoura Univ. 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čabarkapa, I.; Lazarević, J.; Rakita, S.; Tomičić, Z.; Joksimović, A.; Joksimović, D.; Drakulović, D. Comparative Analysis of the Chemical Composition of the Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus Claw Meat from Two Distinct Localities in Adriatic Coastal Waters; Institute of Marine Biology, University of Montenegro: Podgorica, Montenegro, 2022; ISBN 978-9940-9613-3-6. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, F.; Attanzio, A.; Marretta, L.; Luparello, C.; Indelicato, S.; Bongiorno, D.; Barone, G.; Tesoriere, L.; Giardina, I.C.; Abruscato, G.; et al. Bioactive Molecules from the Invasive Blue Crab Callinectes Sapidus Exoskeleton: Evaluation of Reducing, Radical Scavenging, and Antitumor Activities. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamburini, E. The Blue Treasure: Comprehensive Biorefinery of Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus). Foods 2024, 13, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çelik, M.; Türeli, C.; Çelik, M.; Yanar, Y.; Erdem, Ü.; Küçükgülmez, A. Fatty Acid Composition of the Blue Crab (Callinectes Sapidus Rathbun, 1896) in the North Eastern Mediterranean. Food Chem. 2004, 88, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahergorabi, R.; Jaczynski, J. Seafood Proteins and Human Health. In Fish and Fish Oil in Health and Disease Prevention; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Energy and Protein Requirements. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/aa040e/aa040e00.htm?utm (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Kuley, E.; Özoğul, F.; Özogul, Y.; Olgunoglu, A.I. Comparison of Fatty Acid and Proximate Compositions of the Body and Claw of Male and Female Blue Crabs (Callinectes sapidus) from Different Regions of the Mediterranean Coast. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 59, 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, Y.A.; Al-Harthi, M.A.; Korish, M.A.; Shiboob, M.M. Fatty Acid and Cholesterol Profiles, Hypocholesterolemic, Atherogenic, and Thrombogenic Indices of Broiler Meat in the Retail Market. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bosco, A.; Cavallo, M.; Menchetti, L.; Angelucci, E.; Cartoni Mancinelli, A.; Vaudo, G.; Marconi, S.; Camilli, E.; Galli, F.; Castellini, C.; et al. The Healthy Fatty Index Allows for Deeper Insights into the Lipid Composition of Foods of Animal Origin When Compared with the Atherogenic and Thrombogenicity Indexes. Foods 2024, 13, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussavi Javardi, M.S.; Madani, Z.; Movahedi, A.; Karandish, M.; Abbasi, B. The Correlation between Dietary Fat Quality Indices and Lipid Profile with Atherogenic Index of Plasma in Obese and Non-Obese Volunteers: A Cross-Sectional Descriptive-Analytic Case-Control Study. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, J.; Huang, L.; Wu, B.; Wu, C.; He, J.; Bai, Z. PcASTA in Procambarus Clarkii, a Novel Astaxanthin Gene Affecting Shell Color. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 10, 1343126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.T.; Ashour, M.; Abbas, E.M.; Alsaqufi, A.S.; Kelany, M.S.; El-Sawy, M.A.; Sharawy, Z.Z. Growth Performance, Immune-Related and Antioxidant Genes Expression, and Gut Bacterial Abundance of Pacific White Leg Shrimp, Litopenaeus Vannamei, Dietary Supplemented With Natural Astaxanthin. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 874172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Shahidi, F. Upcycling Shellfish Waste: Distribution of Amino Acids, Minerals, and Carotenoids in Body Parts of North Atlantic Crab and Shrimp. Foods 2024, 13, 2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaqoob, Z.; Arshad, M.S.; Imran, M.; Munir, H.; Qaisrani, T.B.; Khalid, W.; Asghar, Z.; Suleria, H.A.R. Mechanistic Role of Astaxanthin Derived from Shrimp against Certain Metabolic Disorders. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carotenoids—ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/chapter/edited-volume/abs/pii/B9780443299834000090?utm (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Song, G.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, J.; Liu, Z.; Quan, J.; Zhu, L. Effects of Astaxanthin on Growth Performance, Gut Structure, and Intestinal Microorganisms of Penaeus Vannamei under Microcystin-LR Stress. Animals 2023, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, S.; Yuan, J.; Li, F. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Molecular Mechanism Involved in Carotenoid Absorption and Metabolism in the Ridgetail White Prawn Exopalaemon Carinicauda. Animals 2025, 15, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimat, V.; Rathod, N.; Čagalj, M.; Hamed, I.; Generalić Mekinić, I. Astaxanthin from Crustaceans and Their Byproducts: A Bioactive Metabolite Candidate for Therapeutic Application. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brai, A.; Brogi, E.; Tarchi, F.; Poggialini, F.; Vagaggini, C.; Simoni, S.; Francardi, V.; Dreassi, E. Exploitation of the Nutraceutical Potential of the Infesting Seaweed Chaetomorpha Linum as a Yellow Mealworms’ Feed: Focus on Nutrients and Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2025, 14, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, F.; Di Gaudio, F.; Attanzio, A.; Marretta, L.; Luparello, C.; Indelicato, S.; Bongiorno, D.; Barone, G.; Tesoriere, L.; Giardina, I.C.; et al. Bioactive Molecules from the Exoskeleton of Procambarus Clarkii: Reducing Capacity, Radical Scavenger, and Antitumor and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Xie, S.; Zhan, W.; Peng, H.; Cao, H.; Tang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, T.; Jin, M.; Zhou, Q. Dietary Astaxanthin Can Promote the Growth and Motivate Lipid Metabolism by Improving Antioxidant Properties for Swimming Crab, Portunus Trituberculatus. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.; Skonberg, D.I.; Myracle, A.D. Anti-Hyperglycemic Effects of Green Crab Hydrolysates Derived by Commercially Available Enzymes. Foods 2020, 9, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pengwei, H.; Tong, Y.I.; Honghui, L.I.; Hao, W.U.; Yan, L.I.; Wuying, C.H.U. Study on Hypoglycemic and Lipid-Lowering Activity of Shrimp Shell-Derived Enzymatic Hydrolysate and Peptide Sequence Function Analysis. Food Mach. 2024, 40, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Han, Q.; Koyama, T.; Ishizaki, S. Preparation, Purification and Characterization of Antibacterial and ACE Inhibitory Peptides from Head Protein Hydrolysate of Kuruma Shrimp, Marsupenaeus Japonicus. Molecules 2023, 28, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, X.; Yan, P.; Sun, R.; Kan, G.; Zhou, Y. Identification and Functional Mechanism of Novel Angiotensin I Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Dipeptides from Xerocomus Badius Cultured in Shrimp Processing Waste Medium. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 5089270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Zhang, C.; Hong, P.; Ji, H.; Hao, J. Purification and Identification of an ACE Inhibitory Peptide from the Peptic Hydrolysate of Acetes Chinensis and Its Antihypertensive Effects in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brai, A.; Neri, C.; Tarchi, F.; Poggialini, F.; Vagaggini, C.; Frosinini, R.; Simoni, S.; Francardi, V.; Dreassi, E. Upcycling Milk Industry Byproducts into Tenebrio Molitor Larvae: Investigation on Fat, Protein, and Sugar Composition. Foods 2024, 13, 3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Stanley, G.H.S. A Simple Method For The Isolation And Purification Of Total Lipides From Animal Tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brai, A.; Hasanaj, A.; Vagaggini, C.; Poggialini, F.; Dreassi, E. Infesting Seaweeds as a Novel Functional Food: Analysis of Nutrients, Antioxidants and ACE Inhibitory Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brai, A.; Vagaggini, C.; Pasqualini, C.; Poggialini, F.; Tarchi, F.; Francardi, V.; Dreassi, E. Use of Distillery By-Products asTenebrio Molitor Mealworm Feed Supplement. J. Insects Food Feed. 2023, 9, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotti, M.; De Pascali, S.A.; Del Coco, L.; Migoni, D.; Carrozzo, L.; Mancinelli, G.; Fanizzi, F.P. 1 H NMR Metabolomic Profiling of the Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus) from the Adriatic Sea (SE Italy): A Comparison with Warty Crab (Eriphia verrucosa), and Edible Crab (Cancer pagurus). Food Chem. 2016, 196, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brai, A.; Poggialini, F.; Trivisani, C.I.; Vagaggini, C.; Tarchi, F.; Francardi, V.; Dreassi, E. Efficient Use of Agricultural Waste to Naturally fortifyTenebrio Molitor Mealworms and Evaluation of Their Nutraceutical Properties. J. Insects Food Feed. 2023, 9, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Silva, J.; Bessa, R.J.B.; Santos-Silva, F. Effect of Genotype, Feeding System and Slaughter Weight on the Quality of Light Lambs. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2002, 77, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, H. Nutritional Indices for Assessing Fatty Acids: A Mini-Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbricht, T.L.V.; Southgate, D.A.T. Coronary Heart Disease: Seven Dietary Factors. Lancet 1991, 338, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Water (g/100 g FW) | Fats (g/100 g FW) | Proteins (g/100 g FW) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| MB | 77.3 ± 0.53 | 0.65 ± 0.04 b | 18.51 ± 0.65 |

| MC | 76.91 ± 0.39 | 0.49 ± 0.02 a | 19.01 ± 0.68 |

| FB | 76.47 ± 0.75 | 0.64 ± 0.06 b | 19.41 ± 0.91 |

| FC | 76.72 ± 0.9 | 0.47 ± 0.06 a | 18.02 ± 0.48 |

| AA | MB | MC | FB | FC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | ±SD | Mean | ±SD | Mean | ±SD | Mean | ±SD | |

| His | 0.314 | 0.05 | 0.295 | 0.03 | 0.310 | 0.06 | 0.342 | 0.05 |

| Thr | 0.331 | 0.02 a | 0.195 | 0.03 b | 0.348 | 0.04 a | 0.275 | 0.04 a |

| Val | 0.277 | 0.01 a | 0.270 | 0.02 a | 0.115 | 0.04 b | 0.125 | 0.02 b |

| Met + Cys | 0.613 | 0.09 | 0.618 | 0.05 | 0.628 | 0.09 | 0.645 | 0.05 |

| Lys | 2.226 | 0.34 | 2.112 | 0.50 | 2.021 | 0.45 | 2.048 | 0.32 |

| Ile | 0.420 | 0.06 | 0.344 | 0.04 | 0.327 | 0.04 | 0.438 | 0.04 |

| Leu | 0.476 | 0.03 | 0.558 | 0.09 | 0.671 | 0.08 | 0.659 | 0.09 |

| Phe + Tyr | 0.171 | 0.05 | 0.160 | 0.03 | 0.197 | 0.04 | 0.187 | 0.06 |

| Total EAA | 4.827 | 0.87 | 4.559 | 0.79 | 4.617 | 0.84 | 4.718 | 0.64 |

| Met | 0.415 | 0.05 a | 0.426 | 0.02 a | 0.503 | 0.05 a | 0.524 | 0.02 b |

| Cys | 0.198 | 0.04 | 0.192 | 0.04 | 0.125 | 0.04 | 0.121 | 0.03 |

| Phe | 0.059 | 0.03 | 0.056 | 0.02 | 0.076 | 0.02 | 0.069 | 0.03 |

| Tyr | 0.112 | 0.02 | 0.104 | 0.01 | 0.121 | 0.02 | 0.118 | 0.03 |

| MB | MC | FB | FC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SD | % | SD | % | SD | % | SD | |

| C12:0 | 1.234 | 0.561 a | 2.181 | 0.070 a | 3.502 | 0.273 b | 2.505 | 0.382 a |

| C14:0 | 1.010 | 0.342 | 0.793 | 0.033 | 0.732 | 0.000 | 0.676 | 0.129 |

| C15:0 | 0.596 | 0.055 | 0.612 | 0.058 | 0.494 | 0.080 | 0.601 | 0.068 |

| C16:0 | 17.444 | 0.428 | 17.002 | 1.730 | 17.170 | 0.577 | 15.602 | 1.056 |

| C17:0 | 1.819 | 0.192 | 1.811 | 0.235 | 1.894 | 0.041 | 1.855 | 0.077 |

| C18:0 | 10.520 | 1.306 a | 12.257 | 1.826 ab | 14.182 | 0.145 b | 13.393 | 0.589 b |

| C20:0 | 0.697 | 0.524 | 0.345 | 0.296 | 0.729 | 0.139 | 0.602 | 0.005 |

| Σ SFA | 33.720 | 0.434 a | 33.981 | 3.585 a | 38.703 | 0.978 b | 35.234 | 2.306 a |

| C16:1 Δ 9 | 2.528 | 0.569 | 2.658 | 0.130 | 1.664 | 0.068 | 1.537 | 0.076 |

| C16:1 Δ 11 | 1.064 | 0.171 | 1.103 | 0.172 | 0.664 | 0.080 | 0.664 | 0.017 |

| C18:1 Δ 9 | 16.256 | 1.145 ab | 17.673 | 1.186 b | 14.793 | 0.122 a | 13.878 | 0.383 a |

| C20:1 Δ 11 | 0.914 | 0.052 | 0.822 | 0.319 | 0.923 | 0.057 | 1.079 | 0.051 |

| Σ MUFA | 20.844 | 0.435 b | 21.492 | 0.163 b | 18.045 | 0.191 a | 17.403 | 0.353 a |

| C16:2 (Δ 9.11) | 0.578 | 0.014 | 0.837 | 0.089 | 0.480 | 0.004 | 0.439 | 0.020 |

| C18:2 (Δ 9.12) | 9.156 | 0.928 | 9.759 | 1.164 | 10.169 | 1.515 | 10.716 | 0.092 |

| C18:3 (Δ 6.9.12) | 1.959 | 0.090 | 1.867 | 0.261 | 1.596 | 0.245 | 1.844 | 0.111 |

| C20:2 (Δ 11.14) | 1.373 | 0.202 | 0.215 | 0.038 | 1.089 | 0.107 | 0.144 | 0.021 |

| C20:4 (Δ 5.8.11.14) | 15.619 | 1.871 bc | 14.532 | 0.629 b | 10.307 | 2.073 a | 16.787 | 1.090 c |

| C20:5 (Δ 5.8.11.14.17) | 10.295 | 0.363 | 10.730 | 0.726 | 10.742 | 0.392 | 11.272 | 0.638 |

| C22:6 (Δ4.7.10.13.16.19) | 7.795 | 0.813 ab | 7.421 | 0.324 ab | 8.871 | 1.144 b | 6.407 | 0.120 a |

| Σ PUFA | 45.435 | 0.001 b | 44.527 | 3.422 ab | 43.253 | 1.169 a | 48.510 | 1.298 c |

| ω6/ω3 | 1.407 | 0.098 b | 1.416 | 0.012 b | 1.126 | 0.027 a | 1.672 | 0.017 c |

| AI | 0.354 | 0.036 | 0.339 | 0.005 | 0.385 | 0.020 | 0.322 | 0.042 |

| TI | 0.375 | 0.006 | 0.377 | 0.006 | 0.407 | 0.021 | 0.390 | 0.036 |

| HH | 3.095 | 0.247 a | 3.105 | 0.490 ab | 2.716 | 0.157 a | 3.295 | 0.394 b |

| HPI | 2.843 | 0.292 | 2.977 | 0.420 | 2.601 | 0.135 | 3.138 | 0.408 |

| MB | MC | FB | FC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astaxanthin (µg/100 g FW) | nq | 67.1 ± 9.13 b | nq | 13.58 ± 4.02 a |

| Inhibitory % | ||

|---|---|---|

| α-Glucosidase | ACE | |

| MB | 47.07 ± 2.31 a | 97.39 ± 0.98 |

| MC | 57.37 ± 3.16 b | 97.74 ± 1.25 |

| FB | 54.19 ± 2.05 b | 97.16 ± 1.91 |

| FC | 62.21 ± 2.13 c | 96.07 ± 1.56 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Brai, A.; Tiberio, L.; Chiti, M.; Poggialini, F.; Vagaggini, C.; Consales, G.; Marsili, L.; Dreassi, E. From Ecological Threat to Bioactive Resource: The Nutraceutical Components of Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010381

Brai A, Tiberio L, Chiti M, Poggialini F, Vagaggini C, Consales G, Marsili L, Dreassi E. From Ecological Threat to Bioactive Resource: The Nutraceutical Components of Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010381

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrai, Annalaura, Lorenzo Tiberio, Matteo Chiti, Federica Poggialini, Chiara Vagaggini, Guia Consales, Letizia Marsili, and Elena Dreassi. 2026. "From Ecological Threat to Bioactive Resource: The Nutraceutical Components of Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010381

APA StyleBrai, A., Tiberio, L., Chiti, M., Poggialini, F., Vagaggini, C., Consales, G., Marsili, L., & Dreassi, E. (2026). From Ecological Threat to Bioactive Resource: The Nutraceutical Components of Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010381