Porphyromonas gingivalis Bundled Fimbriae Interact with Outer Membrane Vesicles, Commensals and Fibroblasts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Bundling of FimA Fimbriae

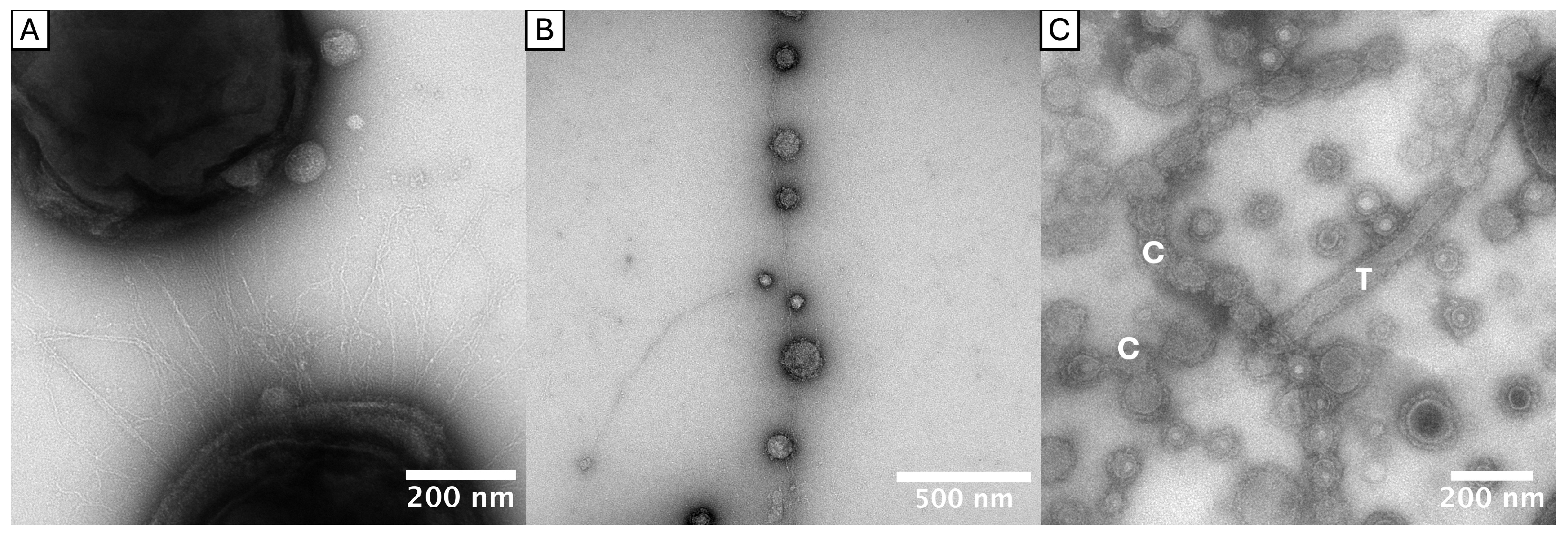

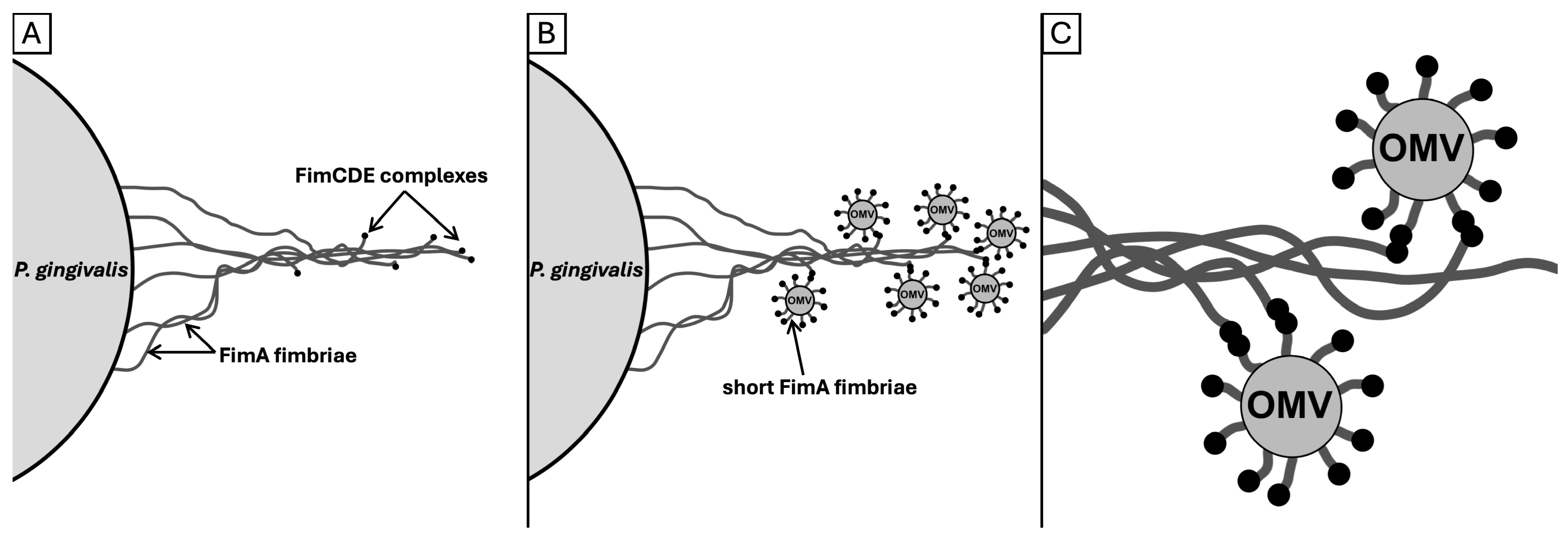

2.2. Tubular and Chain-like Outer Membrane Extensions as Well as Fimbriae-Associated OMVs

2.3. Interactions with S. oralis and F. nucleatum

2.4. Interactions with Gingival Fibroblasts

2.5. Quantities and Ratios of FimA and FimCDE in OMVs

3. Discussion

3.1. Confirmation of the Bundling Phenomenon Across a Diverse Range of FimA Types

3.2. New Insights in OMV Morphologies/OMEs

3.3. FAVs and the Role of FimCDE

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

4.2. Co-Incubation with Oral Commensal Bacteria

4.3. Co-Incubation with Gingival Fibroblasts

4.4. Electron Microscopic Examination

4.5. Vesicle Preparation

4.6. Proteomic Analysis of OMV Content

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TEM | Transmission electron micrography |

| SEM | Scanning electron micrography |

| OMV | Outer membrane vesicle |

| FAV | Fimbriae-associated OMV |

| OME | Outer membrane extension |

| P. gingivalis | Porphyromonas gingivalis |

| PD | Periodontal diseases |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| CR3 | Complement receptor 3 |

| CXCR4 | CXC-chemokine receptor 4 |

| PPAD | Peptidyl arginine deiminase |

| S. oralis | Streptococcus oralis |

| F. nucleatum | Fusobacterium nucleatum |

| HGF | Human gingival fibroblast |

| P. gulae | Porphyromonas gulae |

| EDSL | Electron-dense surface layer |

| iBAQ | Intensity-based absolute quantification |

| MV | Mean value |

| MR | Mean ratio |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| Ns | Non-significant |

| Ffp1 | Filament-forming protein |

| ECT | Electron cryo-tomography |

| NTA | Nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| FA | Formic acid |

| ACN | Acetonitrile |

| DIA | Data-independent acquisition |

References

- Socransky, S.S.; Haffajee, A.D.; Cugini, M.A.; Smith, C.; Kent, R.L. Microbial Complexes in Subgingival Plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1998, 25, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenkein, H.A.; Papapanou, P.N.; Genco, R.; Sanz, M. Mechanisms Underlying the Association between Periodontitis and Atherosclerotic Disease. Periodontology 2000 2020, 83, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moen, K.; Brun, J.G.; Valen, M.; Skartveit, L.; Eribe, E.K.R.; Olsen, I.; Jonsson, R. Synovial Inflammation in Active Rheumatoid Arthritis and Psoriatic Arthritis Facilitates Trapping of a Variety of Oral Bacterial DNAs. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2006, 24, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dominy, S.S.; Lynch, C.; Ermini, F.; Benedyk, M.; Marczyk, A.; Konradi, A.; Nguyen, M.; Haditsch, U.; Raha, D.; Griffin, C.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s Disease Brains: Evidence for Disease Causation and Treatment with Small-Molecule Inhibitors. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Hao, M.; Shi, N.; Wang, X.; Yuan, L.; Yuan, H.; Wang, X. Porphyromonas gingivalis: A Potential Trigger of Neurodegenerative Disease. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1482033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, R.; Mizutani, K.; Gohda, T.; Gotoh, H.; Matsuyama, Y.; Aoyama, N.; Matsuura, T.; Kido, D.; Takeda, K.; Izumi, Y.; et al. Association between Circulating Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptors and Oral Bacterium in Patients Receiving Hemodialysis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2021, 25, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madianos, P.N.; Bobetsis, Y.A.; Offenbacher, S. Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (APOs) and Periodontal Disease: Pathogenic Mechanisms. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, S170–S180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Liang, S.; Payne, M.A.; Hashim, A.; Jotwani, R.; Eskan, M.A.; McIntosh, M.L.; Alsam, A.; Kirkwood, K.L.; Lambris, J.D.; et al. A Low-Abundance Biofilm Species Orchestrates Inflammatory Periodontal Disease through the Commensal Microbiota and the Complement Pathway. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 10, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Darveau, R.P.; Curtis, M.A. The Keystone Pathogen Hypothesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, R.J.; Koo, H.; Hajishengallis, G. The Oral Microbiota: Dynamic Communities and Host Interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 745–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, T.; Krauss, J.L.; Abe, T.; Jotwani, R.; Triantafilou, M.; Triantafilou, K.; Hashim, A.; Hoch, S.; Curtis, M.A.; Nussbaum, G.; et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis Manipulates Complement and TLR Signaling to Uncouple Bacterial Clearance from Inflammation and Promote Dysbiosis. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 768–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, S.; Krauss, J.L.; Domon, H.; McIntosh, M.L.; Hosur, K.B.; Qu, H.; Li, F.; Tzekou, A.; Lambris, J.D.; Hajishengallis, G. The C5a Receptor Impairs IL-12–Dependent Clearance of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Is Required for Induction of Periodontal Bone Loss. J. Immunol. 2011, 186, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makkawi, H.; Hoch, S.; Burns, E.; Hosur, K.; Hajishengallis, G.; Kirschning, C.J.; Nussbaum, G. Porphyromonas gingivalis Stimulates TLR2-PI3K Signaling to Escape Immune Clearance and Induce Bone Resorption Independently of MyD88. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Krauss, J.L.; Domon, H.; Hosur, K.B.; Liang, S.; Magotti, P.; Triantafilou, M.; Triantafilou, K.; Lambris, J.D.; Hajishengallis, G. Microbial Hijacking of Complement–Toll-like Receptor Crosstalk. Sci. Signal. 2010, 3, ra11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amano, A. Bacterial Adhesins to Host Components in Periodontitis. Periodontology 2000 2010, 52, 12–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G.; Shakhatreh, M.-A.K.; Wang, M.; Liang, S. Complement Receptor 3 Blockade Promotes IL-12-Mediated Clearance of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Negates Its Virulence In Vivo1. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 2359–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, F.; Takahashi, K.; Nodasaka, Y.; Suzuki, T. Purification and Characterization of a Novel Type of Fimbriae from the Oral Anaerobe Bacteroides gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 1984, 160, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, N.; Sojar, H.T.; Cho, M.I.; Genco, R.J. Isolation and Characterization of a Minor Fimbria from Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 1996, 64, 4788–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, K.; Hasegawa, Y.; Yoshida, Y.; Yoshimura, F. Novel Fimbrilin PGN_1808 in Porphyromonas gingivalis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, M.J. Characterization of the Porphyromonas gingivalis Protein PG1881 and Its Roles in Outer Membrane Vesicle Biogenesis and Biofilm Formation. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia, 2016. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11343/219179 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Xu, Q.; Shoji, M.; Shibata, S.; Naito, M.; Sato, K.; Elsliger, M.-A.; Grant, J.C.; Axelrod, H.L.; Chiu, H.-J.; Farr, C.L.; et al. A Distinct Type of Pilus from the Human Microbiome. Cell 2016, 165, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña-Amador, L.; Barloy-Hubler, F. In Silico Analysis of Ffp1, an Ancestral Porphyromonas Spp. Fimbrillin, Shows Differences with Fim and Mfa. Access Microbiol. 2024, 6, 000771.v3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, S.; Shoji, M.; Okada, K.; Matsunami, H.; Matthews, M.M.; Imada, K.; Nakayama, K.; Wolf, M. Structure of Polymerized Type V Pilin Reveals Assembly Mechanism Involving Protease-Mediated Strand Exchange. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enersen, M.; Nakano, K.; Amano, A. Porphyromonas gingivalis Fimbriae. J. Oral Microbiol. 2013, 5, 20265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, H.L.; Abdelbary, M.M.H.; Buhl, E.M.; Kuppe, C.; Conrads, G. Exploring the Genetic and Functional Diversity of Porphyromonas gingivalis Long Fimbriae. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2023, 38, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, Y.; Nagano, K. Porphyromonas gingivalis FimA and Mfa1 Fimbriae: Current Insights on Localization, Function, Biogenesis, and Genotype. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2021, 57, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T.; Morishima, S.; Takahashi, I.; Hamada, S. Molecular Cloning and Sequencing of the Fimbrilin Gene of Porphyromonas gingivalis Strains and Characterization of Recombinant Proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993, 197, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, I.; Amano, A.; Kimura, R.K.; Nakamura, T.; Kawabata, S.; Hamada, S. Distribution and Molecular Characterization of Porphyromonas gingivalis Carrying a New Type of fimA Gene. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2000, 38, 1909–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, I.; Amano, A.; Ohara-Nemoto, Y.; Endoh, N.; Morisaki, I.; Kimura, S.; Kawabata, S.; Hamada, S. Identification of a New Variant of fimA Gene of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Its Distribution in Adults and Disabled Populations with Periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2002, 37, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, K.; Hasegawa, Y.; Murakami, Y.; Nishiyama, S.; Yoshimura, F. FimB Regulates FimA Fimbriation in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coats, S.R.; Kantrong, N.; To, T.T.; Jain, S.; Genco, C.A.; McLean, J.S.; Darveau, R.P. The Distinct Immune-Stimulatory Capacities of Porphyromonas gingivalis Strains 381 and ATCC 33277 Are Determined by the fimB Allele and Gingipain Activity. Infect. Immun. 2019, 87, e00319-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, K.; Hasegawa, Y.; Abiko, Y.; Yoshida, Y.; Murakami, Y.; Yoshimura, F. Porphyromonas gingivalis FimA Fimbriae: Fimbrial Assembly by fimA Alone in the fim Gene Cluster and Differential Antigenicity among fimA Genotypes. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishiyama, S.; Murakami, Y.; Nagata, H.; Shizukuishi, S.; Kawagishi, I.; Yoshimura, F. Involvement of Minor Components Associated with the FimA Fimbriae of Porphyromonas gingivalis in Adhesive Functions. Microbiology 2007, 153, 1916–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Shakhatreh, M.-A.K.; James, D.; Liang, S.; Nishiyama, S.; Yoshimura, F.; Demuth, D.R.; Hajishengallis, G. Fimbrial Proteins of Porphyromonas gingivalis Mediate In Vivo Virulence and Exploit TLR2 and Complement Receptor 3 to Persist in Macrophages. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 2349–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, D.L.; Nishiyama, S.; Liang, S.; Wang, M.; Triantafilou, M.; Triantafilou, K.; Yoshimura, F.; Demuth, D.R.; Hajishengallis, G. Host Adhesive Activities and Virulence of Novel Fimbrial Proteins of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 3294–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wielento, A.; Bereta, G.P.; Szczęśniak, K.; Jacuła, A.; Terekhova, M.; Artyomov, M.N.; Hasegawa, Y.; Grabiec, A.M.; Potempa, J. Accessory Fimbrial Subunits and PPAD Are Necessary for TLR2 Activation by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2023, 38, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielento, A.; Bereta, G.P.; Łagosz-Ćwik, K.B.; Eick, S.; Lamont, R.J.; Grabiec, A.M.; Potempa, J. TLR2 Activation by Porphyromonas gingivalis Requires Both PPAD Activity and Fimbriae. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 823685, Corrigendum in Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1476001. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1476001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantri, C.K.; Chen, C.; Dong, X.; Goodwin, J.S.; Pratap, S.; Paromov, V.; Xie, H. Fimbriae-mediated Outer Membrane Vesicle Production and Invasion of Porphyromonas gingivalis. MicrobiologyOpen 2015, 4, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohel, I.; Puente, J.L.; Murray, W.J.; Vuopio-Varkila, J.; Schoolnik, G.K. Cloning and Characterization of the Bundle-Forming Pilin Gene of Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and Its Distribution in Salmonella Serotypes. Mol. Microbiol. 1993, 7, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J.; Monteiro-Neto, V.; Ledesma, M.A.; Jordan, D.M.; Francetic, O.; Kaper, J.B.; Puente, J.L.; Girón, J.A. Intestinal Adherence Associated with Type IV Pili of Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giltner, C.L.; Nguyen, Y.; Burrows, L.L. Type IV Pilin Proteins: Versatile Molecular Modules. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 740–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara-Takahashi, K.; Watanabe, T.; Shimogishi, M.; Shibasaki, M.; Umeda, M.; Izumi, Y.; Nakagawa, I. Phylogenetic Diversity in fim and mfa Gene Clusters between Porphyromonas gingivalis and Porphyromonas gulae, as a Potential Cause of Host Specificity. J. Oral Microbiol. 2020, 12, 1775333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa, K.; Duncan, M.J. Histidine Kinase-Mediated Production and Autoassembly of Porphyromonas gingivalis Fimbriae. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 1975–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Peng, B.; Yang, Q.; Glew, M.D.; Veith, P.D.; Cross, K.J.; Goldie, K.N.; Chen, D.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.; Dashper, S.G.; et al. The Outer Membrane Protein LptO Is Essential for the O-Deacylation of LPS and the Co-Ordinated Secretion and Attachment of A-LPS and CTD Proteins in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 79, 1380–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veith, P.D.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Gorasia, D.G.; Chen, D.; Glew, M.D.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Cecil, J.D.; Holden, J.A.; Reynolds, E.C. Porphyromonas gingivalis Outer Membrane Vesicles Exclusively Contain Outer Membrane and Periplasmic Proteins and Carry a Cargo Enriched with Virulence Factors. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 2420–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyvad, B.; Kilian, M. Microbiology of the Early Colonization of Human Enamel and Root Surfaces in Vivo. Scand. J. Dent. Res. 1987, 95, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; Nagata, H.; Kuboniwa, M.; Kataoka, K.; Nishida, N.; Tanaka, M.; Shizukuishi, S. Characterization of Binding of Streptococcus oralis Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase to Porphyromonas gingivalis Major Fimbriae. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 5475–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, A.; Fujiwara, T.; Nagata, H.; Kuboniwa, M.; Sharma, A.; Sojar, H.T.; Genco, R.J.; Hamada, S.; Shizukuishi, S. Porphyromonas gingivalis Fimbriae Mediate Coaggregation with Streptococcus oralis through Specific Domains. J. Dent. Res. 1997, 76, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolenbrander, P.E.; London, J. Adhere Today, Here Tomorrow: Oral Bacterial Adherence. J. Bacteriol. 1993, 175, 3247–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanhäusser, B.; Busse, D.; Li, N.; Dittmar, G.; Schuchhardt, J.; Wolf, J.; Chen, W.; Selbach, M. Global Quantification of Mammalian Gene Expression Control. Nature 2011, 473, 337–342, Corrigendum in Nature 2013, 495, 126–127. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierickx, K.; Pauwels, M.; Laine, M.L.; Van Eldere, J.; Cassiman, J.-J.; Van Winkelhoff, A.J.; Van Steenberghe, D.; Quirynen, M. Adhesion of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Serotypes to Pocket Epithelium. J. Periodontol. 2003, 74, 844–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, M.E.; Duncan, M.J. Enhanced Biofilm Formation and Loss of Capsule Synthesis: Deletion of a Putative Glycosyltransferase in Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 5510–5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schembri, M.A.; Blom, J.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Klemm, P. Capsule and Fimbria Interaction in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 2005, 73, 4626–4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.X.; Eichner, H.; Cammer, M.; Weiser, J.N. Inhibitory Effect of Capsule on Natural Transformation of Streptococcus pneumoniae. mBio 2025, 16, e01394-25. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Fang, H.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhou, D.; Yang, R. Reciprocal Regulation of Yersinia pestis Biofilm Formation and Virulence by RovM and RovA. Open Biol. 2016, 6, 150198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, P.S.; Tipler, L.S. An Electron Microscope Survey of the Surface Structures and Hydrophobicity of Oral and Non-Oral Species of the Bacterial Genus Bacteroides. Arch. Oral Biol. 1986, 31, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenier, D.; Mayrand, D. Functional Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles Produced by Bacteroides gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 1987, 55, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrand, D.; Grenier, D. Biological Activities of Outer Membrane Vesicles. Can. J. Microbiol. 1989, 35, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, H.; Hirota, K.; Yoshida, K.; Weng, Y.; He, Y.; Shiotsu, N.; Ikegame, M.; Uchida-Fukuhara, Y.; Tanai, A.; Guo, J. Outer Membrane Vesicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis: Novel Communication Tool and Strategy. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2021, 57, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Long, W.; Yin, Y.; Tan, B.; Liu, C.; Li, H.; Ge, S. Outer Membrane Vesicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis: Recent Advances in Pathogenicity and Associated Mechanisms. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1555868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, M.; Chreifi, G.; Metskas, L.A.; Liedtke, J.; Wood, C.R.; Oikonomou, C.M.; Nicolas, W.J.; Subramanian, P.; Zacharoff, L.A.; Wang, Y.; et al. In Situ Imaging of Bacterial Outer Membrane Projections and Associated Protein Complexes Using Electron Cryo-Tomography. eLife 2021, 10, e73099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.; Schorb, M.; Reintjes, G.; Kolovou, A.; Santarella-Mellwig, R.; Markert, S.; Rhiel, E.; Littmann, S.; Becher, D.; Schweder, T.; et al. Biopearling of Interconnected Outer Membrane Vesicle Chains by a Marine Flavobacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e00829-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Hu, Y.; Odermatt, P.D.; Gonzalez, C.G.; Zhang, L.; Elias, J.E.; Chang, F.; Huang, K.C. Precise Regulation of the Relative Rates of Surface Area and Volume Synthesis in Bacterial Cells Growing in Dynamic Environments. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermilyea, D.M.; Moradali, M.F.; Kim, H.-M.; Davey, M.E. PPAD Activity Promotes Outer Membrane Vesicle Biogenesis and Surface Translocation by Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 2021, 203, e00343-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrugia, C.; Stafford, G.P.; Murdoch, C. Porphyromonas gingivalis Outer Membrane Vesicles Increase Vascular Permeability. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Shiotsu, N.; Uchida-Fukuhara, Y.; Guo, J.; Weng, Y.; Ikegame, M.; Wang, Z.; Ono, K.; Kamioka, H.; Torii, Y.; et al. Outer Membrane Vesicles Derived from Porphyromonas gingivalis Induced Cell Death with Disruption of Tight Junctions in Human Lung Epithelial Cells. Arch. Oral Biol. 2020, 118, 104841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A.B.; Fabian, Z.; Lawrence, C.L.; Morton, G.; Crean, S.; Alder, J.E. An Investigation into the Effects of Outer Membrane Vesicles and Lipopolysaccharide of Porphyromonas gingivalis on Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity, Permeability, and Disruption of Scaffolding Proteins in a Human in Vitro Model. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2022, 86, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Yoshida, K.; Seyama, M.; Hiroshima, Y.; Mekata, M.; Fujiwara, N.; Kudo, Y.; Ozaki, K. Porphyromonas gingivalis Outer Membrane Vesicles in Cerebral Ventricles Activate Microglia in Mice. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 3688–3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashper, S.G.; Mitchell, H.L.; Seers, C.A.; Gladman, S.L.; Seemann, T.; Bulach, D.M.; Chandry, P.S.; Cross, K.J.; Cleal, S.M.; Reynolds, E.C. Porphyromonas gingivalis Uses Specific Domain Rearrangements and Allelic Exchange to Generate Diversity in Surface Virulence Factors. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, Y.; Nagano, K.; Ikai, R.; Izumigawa, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Kitai, N.; Lamont, R.; Murakami, Y.; Yoshimura, F. Localization and Function of the Accessory Protein Mfa3 in Porphyromonas gingivalis Mfa1 Fimbriae. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2013, 28, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuboniwa, M.; Amano, A.; Hashino, E.; Yamamoto, Y.; Inaba, H.; Hamada, N.; Nakayama, K.; Tribble, G.D.; Lamont, R.J.; Shizukuishi, S. Distinct Roles of Long/Short Fimbriae and Gingipains in Homotypic Biofilm Development by Porphyromonas gingivalis. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulbourne, P.A.; Ellen, R.P. Evidence That Porphyromonas (Bacteroides) gingivalis Fimbriae Function in Adhesion to Actinomyces Viscosus. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 5266–5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, M.; Ogawa, S.; Asai, Y.; Takai, Y.; Ogawa, T. Binding of Porphyromonas gingivalis Fimbriae to Treponema denticola Dentilisin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2003, 226, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, K.; Nagata, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Tanaka, J.; Minamino, N.; Shizukuishi, S. Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase of Streptococcus oralis Functions as a Coadhesin for Porphyromonas gingivalis Major Fimbriae. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, N.; Watanabe, K.; Sasakawa, C.; Yoshikawa, M.; Yoshimura, F.; Umemoto, T. Construction and Characterization of a fimA Mutant of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 1994, 62, 1696–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isogai, H.; Isogai, E.; Yoshimura, F.; Suzuki, T.; Kagota, W.; Takano, K. Specific Inhibition of Adherence of an Oral Strain of Bacteroides gingivalis 381 to Epithelial Cells by Monoclonal Antibodies against the Bacterial Fimbriae. Arch. Oral Biol. 1988, 33, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontani, M.; Ono, H.; Shibata, H.; Okamura, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Fujiwara, T.; Kimura, S.; Hamada, S. Cysteine Protease of Porphyromonas gingivalis 381 Enhances Binding of Fimbriae to Cultured Human Fibroblasts and Matrix Proteins. Infect. Immun. 1996, 64, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, T.N.; Kuehn, M.J. Virulence and Immunomodulatory Roles of Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 74, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.P.; Bruderer, R.; Abbott, J.; Arthur, J.S.C.; Brenes, A.J. Optimizing Spectronaut Search Parameters to Improve Data Quality with Minimal Proteome Coverage Reductions in DIA Analyses of Heterogeneous Samples. J. Proteome Res. 2024, 23, 1926–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenfield, A.M.; Ni, J.; Ahmed, M.; Hao, L. Protein Contaminants Matter: Building Universal Protein Contaminant Libraries for DDA and DIA Proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 2022, 21, 2104–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Bandla, C.; Kundu, D.J.; Kamatchinathan, S.; Bai, J.; Hewapathirana, S.; John, N.S.; Prakash, A.; Walzer, M.; Wang, S.; et al. The PRIDE Database at 20 Years: 2025 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53, D543–D553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain Designation | Original Code | Id Name Species | Fimbriae Type 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| OMI 1080 | G 251 | P. gingivalis animal biotype/P. gulae | A |

| OMI 1132 | ATCC 33277 | P. gingivalis | I |

| OMI 1127 | 84Pg1 | P. gingivalis | Ib |

| OMI 883 | AC 27 | P. gingivalis | IIa |

| OMI 778 | AC 38 | P. gingivalis | IIb |

| OMI 1071 | ATCC 49417, RB22D | P. gingivalis | III |

| OMI 629 | W83 | P. gingivalis | IV |

| OMI 1049 | AJW5 (VAG5) | P. gingivalis | IV |

| OMI 622 | Fr. 025/15-1 | P. gingivalis | V |

| OMI 581 | ATCC 35037 | S. oralis | - |

| OMI 1040 | ATCC 25586 | F. nucleatum | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lambertz, J.; Buhl, E.M.; Apel, C.; Preisinger, C.; Conrads, G. Porphyromonas gingivalis Bundled Fimbriae Interact with Outer Membrane Vesicles, Commensals and Fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010383

Lambertz J, Buhl EM, Apel C, Preisinger C, Conrads G. Porphyromonas gingivalis Bundled Fimbriae Interact with Outer Membrane Vesicles, Commensals and Fibroblasts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010383

Chicago/Turabian StyleLambertz, Julian, Eva Miriam Buhl, Christian Apel, Christian Preisinger, and Georg Conrads. 2026. "Porphyromonas gingivalis Bundled Fimbriae Interact with Outer Membrane Vesicles, Commensals and Fibroblasts" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010383

APA StyleLambertz, J., Buhl, E. M., Apel, C., Preisinger, C., & Conrads, G. (2026). Porphyromonas gingivalis Bundled Fimbriae Interact with Outer Membrane Vesicles, Commensals and Fibroblasts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010383