From Gut Dysbiosis to Skin Inflammation in Atopic Dermatitis: Probiotics and the Gut–Skin Axis—Clinical Outcomes and Microbiome Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction and Background

1.1. The Skin and Gut Microbiome

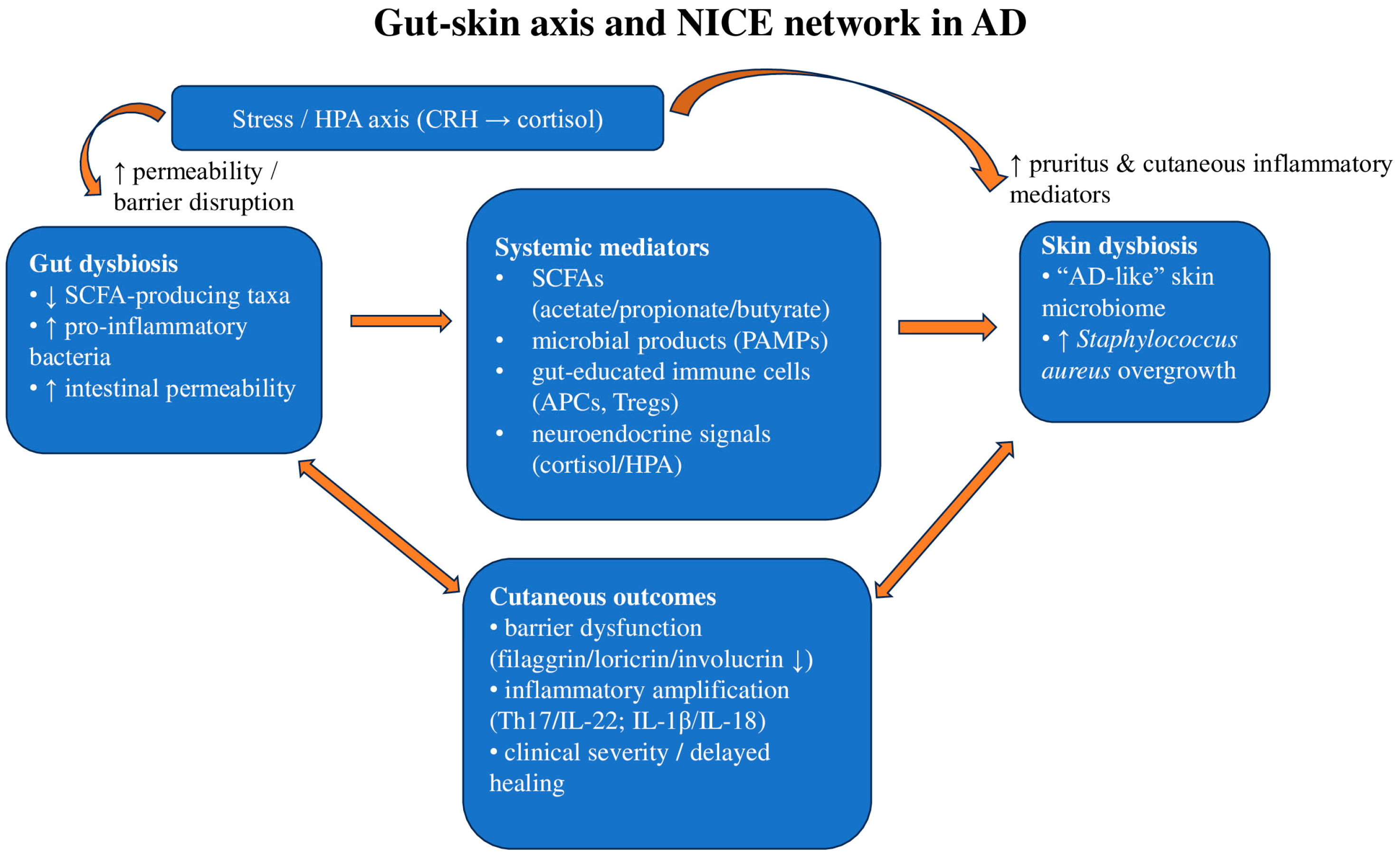

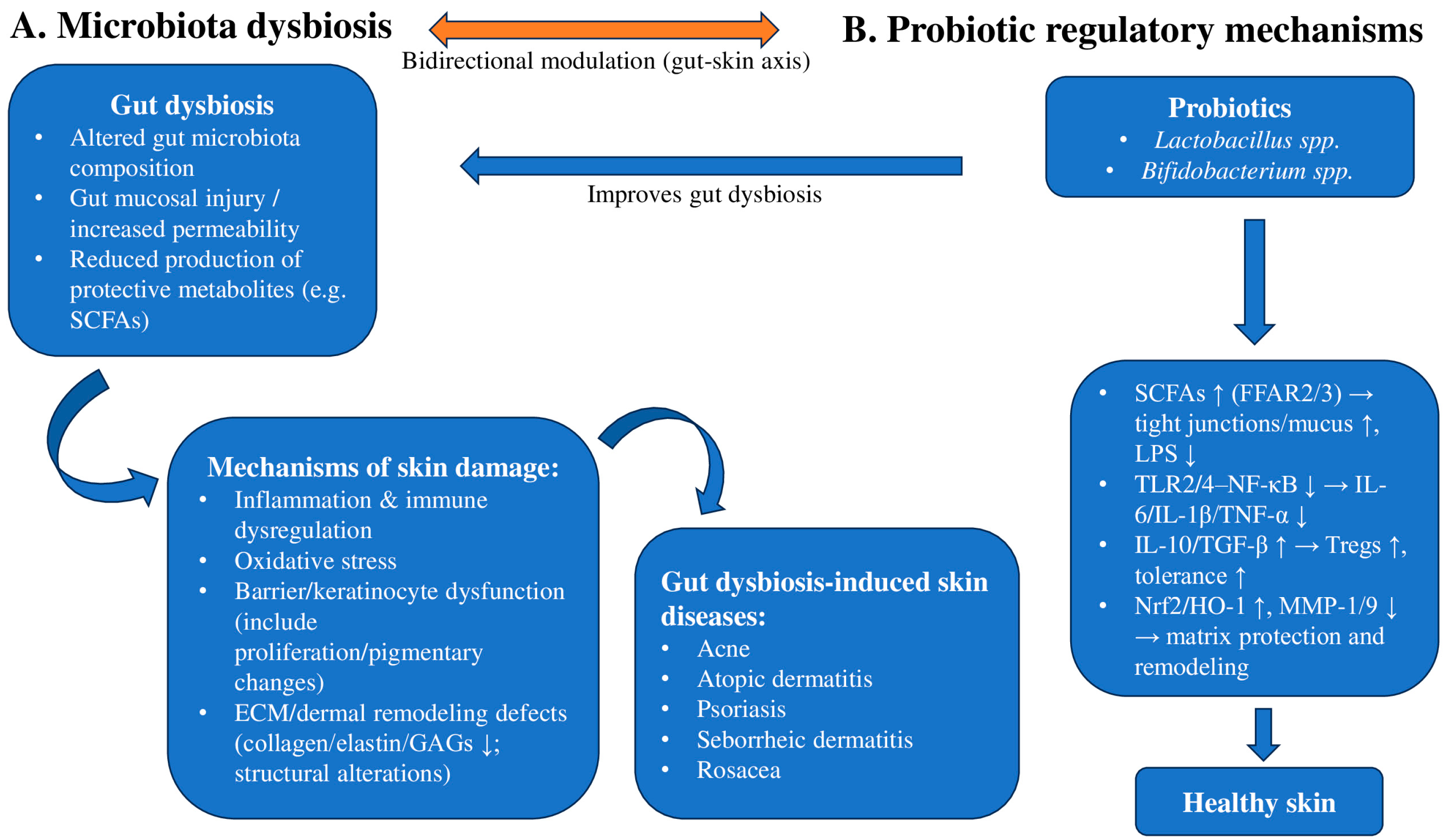

1.2. The Gut–Skin Axis and Neuro-Immuno-Cutaneous-Endocrine (NICE) Network

1.3. Atopic Dermatitis

1.4. AD and the Cutaneous and Gut Microbiome

1.5. Current Standard of Care and Place of Microbiome-Targeted Adjuncts

1.6. Probiotics

1.7. Probiotics and AD

1.8. The Mechanism of Probiotics in Improving Skin Diseases

2. Evidence Synthesis

2.1. Evidence of Gut and Skin Dysbiosis in AD

2.2. Early-Life Colonization and Later AD Phenotypes

2.3. Probiotic/Prebiotic/Synbiotic Interventions in AD

2.4. Mechanistic/Proof-of-Concept Studies

2.5. Other Extracutaneous Microbiomes

2.6. Clinical Evidence Summary (RCTs)

3. Clinical Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

3.1. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium as Dermatologic Probiotics

3.2. Early-Life Microbiome, Hygiene Concept, and AD Risk

3.3. Breadth of Probiotic Effects

3.4. Strain Specificity and Colonization

3.5. Gut–Skin Axis in Chronic Inflammatory Dermatoses

3.6. Toward Personalized/Profiling-Based Use

3.7. Timing and Maternal Supplementation

3.8. Strength of Evidence

3.9. Skin-Targeted Implications

3.10. Targeting Staphylococcus aureus

3.11. Linking Gut–Skin Correction

4. Literature Search Strategy

4.1. RCT-Focused Search for Clinical Evidence

4.2. Narrative Search for Mechanistic and Observational Evidence

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Atopic dermatitis |

| AHR | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| AMP | Antimicrobial peptide |

| CFU | Colony-forming unit |

| CRH | Corticotropin-releasing hormone |

| EASI | Eczema Area and Severity Index |

| FFAR2/GPR43 | Free fatty acid receptor 2/G protein-coupled receptor 43 |

| FFAR3/GPR41 | Free fatty acid receptor 3/G protein-coupled receptor 41 |

| FOXP3 | Forkhead box P3 |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GPCR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| IBS | Irritable bowel syndrome |

| IL-4, -13, -31, -6, -1β, -10 | Interleukin-4, -13, -31, -6, -1β, -10 |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase (e.g., MMP-1, MMP-9) |

| NICE | Neuro-immuno-cutaneous-endocrine |

| NLRP3 | NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PAMP | Pathogen-associated molecular pattern |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| SCORAD | Scoring Atopic Dermatitis |

| TEWL | Transepidermal water loss |

| Th2 | T-helper 2 cell |

| Th17 | T-helper 17 cell |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| Treg | Regulatory T cell |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Mahmud, M.R.; Akter, S.; Tamanna, S.K.; Mazumder, L.; Esti, I.Z.; Banerjee, S.; Akter, S.; Hasan, M.R.; Acharjee, M.; Hossain, M.S.; et al. Impact of Gut Microbiome on Skin Health: Gut-Skin Axis Observed through the Lenses of Therapeutics and Skin Diseases. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2096995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennitti, C.; Calvanese, M.; Gentile, A.; Vastola, A.; Romano, P.; Ingenito, L.; Gentile, L.; Veneruso, I.; Scarano, C.; La Monica, I.; et al. Skin Microbiome Overview: How Physical Activity Influences Bacteria. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, I.; Ramser, A.; Isham, N.; Ghannoum, M.A. The Gut Microbiome as a Major Regulator of the Gut-Skin Axis. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhao, H.; Guo, D.; Zhu, P.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, W. Gut Microbiota Alterations in Moderate to Severe Acne Vulgaris Patients. J. Dermatol. 2018, 45, 1166–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.H.; Kim, J.W.; Park, H.-J.; Hahm, D.-H. Comparative Analysis of the Microbiome across the Gut–Skin Axis in Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; He, C.; An, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, W.; Wang, M.; Shan, Z.; Xie, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. The Role of Short Chain Fatty Acids in Inflammation and Body Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada Venegas, D.; De La Fuente, M.K.; Landskron, G.; González, M.J.; Quera, R.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faber, K.N.; Hermoso, M.A. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 277, Erratum in Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1486. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Furue, M. Regulation of Filaggrin, Loricrin, and Involucrin by IL-4, IL-13, IL-17A, IL-22, AHR, and NRF2: Pathogenic Implications in Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Sapkota, A.; Bae, Y.J.; Choi, S.-H.; Bae, H.J.; Kim, H.-J.; Cho, Y.E.; Choi, Y.-Y.; An, J.-Y.; Cho, S.-Y.; et al. The Anti-Atopic Dermatitis Effects of Mentha Arvensis Essential Oil Are Involved in the Inhibition of the NLRP3 Inflammasome in DNCB-Challenged Atopic Dermatitis BALB/c Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.K.; Patel, K.H.; Huang, R.Y.; Lee, C.N.; Moochhala, S.M. The Gut-Skin Microbiota Axis and Its Role in Diabetic Wound Healing—A Review Based on Current Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilchmann-Diounou, H.; Menard, S. Psychological Stress, Intestinal Barrier Dysfunctions, and Autoimmune Disorders: An Overview. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Su, J. Role of Stress in Skin Diseases: A Neuroendocrine-Immune Interaction View. Brain Behav. Immun. 2024, 116, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sroka-Tomaszewska, J.; Trzeciak, M. Molecular Mechanisms of Atopic Dermatitis Pathogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fania, L.; Moretta, G.; Antonelli, F.; Scala, E.; Abeni, D.; Albanesi, C.; Madonna, S. Multiple Roles for Cytokines in Atopic Dermatitis: From Pathogenic Mediators to Endotype-Specific Biomarkers to Therapeutic Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapin, A.; Rehbinder, E.M.; Macowan, M.; Pattaroni, C.; Lødrup Carlsen, K.C.; Harris, N.L.; Jonassen, C.M.; Landrø, L.; Lossius, A.H.; Nordlund, B.; et al. The Skin Microbiome in the First Year of Life and Its Association with Atopic Dermatitis. Allergy 2023, 78, 1949–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serghiou, I.R.; Webber, M.A.; Hall, L.J. An Update on the Current Understanding of the Infant Skin Microbiome and Research Challenges. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2023, 75, 102364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, C.F.P.; Kilian, M. The Natural History of Cutaneous Propionibacteria, and Reclassification of Selected Species within the Genus Propionibacterium to the Proposed Novel Genera Acidipropionibacterium Gen. Nov., Cutibacterium Gen. Nov. and Pseudopropionibacterium Gen. Nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 4422–4432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.P.; O’Laughlin, B.; Kumar, P.S.; Dabdoub, S.M.; Levy, S.; Myles, I.A.; Hourigan, S.K. Vaginal Delivery Provides Skin Colonization Resistance from Environmental Microbes in the NICU. Clin. Transl. Med. 2023, 13, e1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severn, M.M.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcus Epidermidis and Its Dual Lifestyle in Skin Health and Infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatsuji, T.; Brinton, S.L.; Cavagnero, K.J.; O’Neill, A.M.; Chen, Y.; Dokoshi, T.; Butcher, A.M.; Osuoji, O.C.; Shafiq, F.; Espinoza, J.L.; et al. Competition between Skin Antimicrobial Peptides and Commensal Bacteria in Type 2 Inflammation Enables Survival of S. Aureus. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowsky, R.L.; Sulejmani, P.; Lio, P.A. Atopic Dermatitis: Beyond the Skin and Into the Gut. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J.; Lu, W.; Chen, W. Gut Microbiota, Probiotics, and Their Interactions in Prevention and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis: A Review. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 720393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díez-Madueño, K.; De La Cueva Dobao, P.; Torres-Rojas, I.; Fernández-Gosende, M.; Hidalgo-Cantabrana, C.; Coto-Segura, P. Gut Dysbiosis and Adult Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 14, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Seok, J.K.; Kang, H.C.; Cho, Y.-Y.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.Y. Skin Barrier Abnormalities and Immune Dysfunction in Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pessemier, B.; Grine, L.; Debaere, M.; Maes, A.; Paetzold, B.; Callewaert, C. Gut–Skin Axis: Current Knowledge of the Interrelationship between Microbial Dysbiosis and Skin Conditions. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, A.; Leshem, Y.A.; Taieb, Y.; Baum, S.; Barzilai, A.; Jeddah, D.; Sharon, E.; Koren, O.; Tzach-Nahman, R.; Coppenhagen-Glazer, S.; et al. Association of Adult Atopic Dermatitis with Impaired Oral Health and Oral Dysbiosis: A Case-Control Study. Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris-Tryon, T.A.; Grice, E.A. Microbiota and Maintenance of Skin Barrier Function. Science 2022, 376, 940–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yu, X.; Cheng, G. Human Skin Bacterial Microbiota Homeostasis: A Delicate Balance between Health and Disease. mLife 2023, 2, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Ren, F. The Role of Probiotics in Skin Health and Related Gut–Skin Axis: A Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidbury, R.; Alikhan, A.; Bercovitch, L.; Cohen, D.E.; Darr, J.M.; Drucker, A.M.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Frazer-Green, L.; Paller, A.S.; Schwarzenberger, K.; et al. Guidelines of Care for the Management of Atopic Dermatitis in Adults with Topical Therapies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 89, e1–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.K.; Schneider, L.; Asiniwasis, R.N.; Boguniewicz, M.; De Benedetto, A.; Ellison, K.; Frazier, W.T.; Greenhawt, M.; Huynh, J.; Kim, E.; et al. Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema) Guidelines: 2023 American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters GRADE– and Institute of Medicine–Based Recommendations. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2024, 132, 274–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.M.R.; Drucker, A.M.; Alikhan, A.; Bercovitch, L.; Cohen, D.E.; Darr, J.M.; Eichenfield, L.F.; Frazer-Green, L.; Paller, A.S.; Schwarzenberger, K.; et al. Guidelines of Care for the Management of Atopic Dermatitis in Adults with Phototherapy and Systemic Therapies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 90, e43–e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liscano, Y.; Muñoz Morales, D.; Suarez Daza, F.; Vidal Cañas, S.; Martinez Guevara, D.; Artunduaga Cañas, E. Microbial Interventions for Inflammatory Skin Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriasis. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Fan, X.; Yuan, Z.; Li, D. Probiotic Effects on Skin Health: Comprehensive Visual Analysis and Perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1453755, Erratum in Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1583612. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1453755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhang, J.; Yao, Q.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, X. The Gut-skin Axis: Emerging Insights in Understanding and Treating Skin Diseases through Gut Microbiome Modulation (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2025, 56, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torabi, S.; Nahidi, Y.; Ghasemi, S.Z.; Reihani, A.; Samadi, A.; Ramezanghorbani, N.; Nazari, E.; Davoudi, S. Evaluation of Skin Cancer Prevention Properties of Probiotics. Genes Nutr. 2025, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haykal, D.; Cartier, H.; Dréno, B. Dermatological Health in the Light of Skin Microbiome Evolution. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 3836–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguwa, C.; Enwereji, N.; Santiago, S.; Hine, A.; Kels, G.G.; McGee, J.; Lu, J. Targeting Dysbiosis in Psoriasis, Atopic Dermatitis, and Hidradenitis Suppurativa: The Gut-Skin Axis and Microbiome-Directed Therapy. Clin. Dermatol. 2023, 41, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekrasova, A.I.; Kalashnikova, I.G.; Bobrova, M.M.; Korobeinikova, A.V.; Bakoev, S.Y.; Ashniev, G.A.; Petryaikina, E.S.; Nekrasov, A.S.; Zagainova, A.V.; Lukashina, M.V.; et al. Characteristics of the Gut Microbiota in Regard to Atopic Dermatitis and Food Allergies of Children. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharschmidt, T.C.; Segre, J.A. Skin Microbiome and Dermatologic Disorders. J. Clin. Investig. 2025, 135, e184315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wu, F.; Chen, H.; Tang, B. The Effect of Probiotics in the Prevention of Atopic Dermatitis in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transl. Pediatr. 2023, 12, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilopoulou, E.; Comotti, A.; Douladiris, N.; Konstantinou, G.Ν.; Zuberbier, T.; Alberti, I.; Agostoni, C.; Berni Canani, R.; Bocsan, I.C.; Corsello, A.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Nutritional and Dietary Interventions in Randomized Controlled Trials for Skin Symptoms in Children with Atopic Dermatitis and without Food Allergy: An EAACI Task Force Report. Allergy 2024, 79, 1708–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, L. The Impact of Prebiotics, Probiotics and Synbiotics on the Prevention and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis in Children: An Umbrella Meta-Analysis. Front. Pediatr. 2025, 13, 1498965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrestak, D.; Matijašić, M.; Čipčić Paljetak, H.; Ledić Drvar, D.; Ljubojević Hadžavdić, S.; Perić, M. Skin Microbiota in Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.H.; Yoon, W.; Lee, S.Y.; Shin, H.S.; Lim, M.Y.; Nam, Y.D.; Yoo, Y. Effects of Lactobacillus Pentosus in Children with Allergen-Sensitized Atopic Dermatitis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelotti, A.; Cestone, E.; De Ponti, I.; Giardina, S.; Pisati, M.; Spartà, E.; Tursi, F. Efficacy of a Probiotic Supplement in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Eur. J. Dermatol. EJD 2021, 31, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carucci, L.; Nocerino, R.; Paparo, L.; De Filippis, F.; Coppola, S.; Giglio, V.; Cozzolino, T.; Valentino, V.; Sequino, G.; Bedogni, G.; et al. Therapeutic Effects Elicited by the Probiotic Lacticaseibacillus Rhamnosus GG in Children with Atopic Dermatitis. The Results of the ProPAD Trial. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. Off. Publ. Eur. Soc. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2022, 33, e13836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feito-Rodríguez, M.; Ramírez-Boscá, A.; Vidal-Asensi, S.; Fernandez-Nieto, D.; Ros-Cervera, G.; Alonso-Usero, V.; Prieto-Merino, D.; Núñez-Delegido, E.; Ruzafa-Costas, B.; Sánchez Pellicer, P.; et al. Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Effect of a Mixture of Probiotic Strains on Symptom Severity and Use of Corticosteroids in Children and Adolescents with Atopic Dermatitis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2023, 48, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Auria, E.; Panelli, S.; Lunardon, L.; Pajoro, M.; Paradiso, L.; Beretta, S.; Loretelli, C.; Tosi, D.; Perini, M.; Bedogni, G.; et al. Rice Flour Fermented with Lactobacillus Paracasei CBA L74 in the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis in Infants: A Randomized, Double- Blind, Placebo- Controlled Trial. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 163, 105284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rather, I.A.; Kim, B.-C.; Lew, L.-C.; Cha, S.-K.; Lee, J.H.; Nam, G.-J.; Majumder, R.; Lim, J.; Lim, S.-K.; Seo, Y.-J.; et al. Oral Administration of Live and Dead Cells of Lactobacillus Sakei proBio65 Alleviated Atopic Dermatitis in Children and Adolescents: A Randomized, Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Study. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2021, 13, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, P.D.S.M.A.D.; Maria e Silva, J.; Carregaro, V.; Sacramento, L.A.; Roberti, L.R.; Aragon, D.C.; Carmona, F.; Roxo-Junior, P. Efficacy of Probiotics in Children and Adolescents with Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 833666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakoeswa, C.R.S.; Bonita, L.; Karim, A.; Herwanto, N.; Umborowati, M.A.; Setyaningrum, T.; Hidayati, A.N.; Surono, I.S. Beneficial Effect of Lactobacillus Plantarum IS-10506 Supplementation in Adults with Atopic Dermatitis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2022, 33, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-López, V.; Ramírez-Boscá, A.; Ramón-Vidal, D.; Ruzafa-Costas, B.; Genovés-Martínez, S.; Chenoll-Cuadros, E.; Carrión-Gutiérrez, M.Á.; de la Parte, J.H.; Prieto-Merino, D.; Codoñer, F.M. Effect of Oral Administration of a Mixture of Probiotic Strains on SCORAD Index and Use of Topical Steroids in Young Patients with Moderate Atopic Dermatitis a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Handa, S.; Mahajan, R.; De, D.; Sachdeva, N. Evaluating the Effect of Supplementation with Bacillus Clausii on Therapeutic Outcomes in Atopic Eczema-Results of an Observer-Blinded Parallel-Group Randomized Controlled Study. Indian J. Dermatol. 2022, 67, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, J.; Zhu, W.; Kuang, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Peng, C. Skin and Gut Microbiome in Psoriasis: Gaining Insight Into the Pathophysiology of It and Finding Novel Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 589726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smythe, P.; Wilkinson, H.N. The Skin Microbiome: Current Landscape and Future Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Schulte, J.; Wurpts, G.; Hornef, M.W.; Wolz, C.; Yazdi, A.S.; Burian, M. Transcriptional Profiling of Staphylococcus Aureus during the Transition from Asymptomatic Nasal Colonization to Skin Colonization/Infection in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrześniewska, M.; Wołoszczak, J.; Świrkosz, G.; Szyller, H.; Gomułka, K. The Role of the Microbiota in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis—A Literature Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galla, R.; Mulè, S.; Ferrari, S.; Molinari, C.; Uberti, F. Non-Animal Hyaluronic Acid and Probiotics Enhance Skin Health via the Gut–Skin Axis: An In Vitro Study on Bioavailability and Cellular Impact. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year, Country | Study Design | Population | Intervention Strain and CFU | Duration | Comparator | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| So Hyun Ahn et al., 2020, Korea [45] | double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized study | Children aged 2–13 years with AD | L. pentosus DOSE: NR | 12 weeks | placebo | Decrease in SCORAD |

| Angela MICHELOTTI et al., 2021, Italy [46] | randomized controlled trial (RCT) | 80 adults with mild-to-severe AD Age: NR | mixture of lactobacilli (L. plantarum PBS067, L. reuteri PBS072 and L. rhamnosus LRH020) DOSE: L. plantarum—1 × 109 CFU/daily L. reuteri—1 × 109 CFU/daily L. rhamnosus—1 × 109 CFU/daily | 56 days | Placebo | improvement in skin smoothness, skin moisturization, self-perception; decrease in SCORAD index as well as in the levels of inflammatory markers associated with AD |

| Laura Carucci et al., 2022, Italy [47] | Randomized double-blind, controlled trial | patients aged 6–36 months with AD | Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG Dose: 1 × 1010 CFU/daily | 12 weeks | placebo | Decrease in SCORAD and DLQI |

| Marta Feíto-Rodríguez et al., 2023, Spain [48] | This double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial | 70 participants with AD aged 4–17 years | probiotic mixture of Bifidobacterium lactis, Bifidobacterium longum and Lactobacillus casei Dose: 1 × 109 CFU/daily | 12 weeks | placebo | Decrease in SCORAD |

| Enza D’Auria et al., 2020, Italy [49] | A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Infants with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis, aged 6–36 months | heat-killed Lactobacillus paracasei CBA L74 (fermented rice flour) Dose: 8 g daily (CFU not applicable) | 12 weeks | placebo | Decrease in SCORAD |

| Irfan A. Rather et al., 2020, South Korea [50] | Randomized Double-Blind, and Placebo-Controlled Study | children and adolescents (aged 3–18) with AD | L. sakei proBio65 live and dead cells Dose: 1 × 1010 CFU/daily | 12 weeks | placebo | Decrease in SCORAD |

| Paula Danielle Santa Maria Albuquerque de Andrade et al., 2022, Brazil [51] | double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial | 60 patients aged between 6 months and 19 years with mild, moderate, or severe AD | Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001: 1 × 109 CFU/daily Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM: 1 × 109 CFU/daily Lactobacillus paracasei Lcp-37: 1 × 109 CFU/daily Bifidobacterium lactis HN019: 1 × 109 CFU/daily | 6 months | placebo | Decrease in SCORAD |

| C R S Prakoeswa et al., 2022, Indonesia [52] | randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial | 30 adults with mild and moderate AD | Lactobacillus plantarum IS-10506 Dose: 2 × 1010 CFU/ daily | 8 weeks | placebo | SCORAD ↓ IL-4 ↓ IL-17 ↓ IFN-γ ↑ Foxp3+ ↑ |

| Vicente Navarro-López et al., 2018, Spain [53] | double-blind, placebo-controlled intervention trial | children aged 4–17 years with moderate AD | Bifidobacterium lactis CECT 8145, B longum CECT 7347, and Lactobacillus casei CECT 9104 Dose: 1 × 109 CFU/daily | 12 weeks | Placebo | Decrease in SCORAD; fewer patient-days with topical corticosteroid use for flares |

| Richa Sharma et al., 2022, India [54] | randomized controlled study | 114 children with AD | Bacillus clausii Dose: 4 × 109 CFU/daily | 12 weeks | placebo | SCORAD: no difference IL-17A: no difference; no correlation with severity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Micu, A.E.; Popescu, I.A.; Halip, I.A.; Mocanu, M.; Vâță, D.; Hulubencu, A.L.; Gheucă-Solovăstru, D.F.; Gheucă-Solovăstru, L. From Gut Dysbiosis to Skin Inflammation in Atopic Dermatitis: Probiotics and the Gut–Skin Axis—Clinical Outcomes and Microbiome Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010365

Micu AE, Popescu IA, Halip IA, Mocanu M, Vâță D, Hulubencu AL, Gheucă-Solovăstru DF, Gheucă-Solovăstru L. From Gut Dysbiosis to Skin Inflammation in Atopic Dermatitis: Probiotics and the Gut–Skin Axis—Clinical Outcomes and Microbiome Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):365. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010365

Chicago/Turabian StyleMicu, Adina Elena, Ioana Adriana Popescu, Ioana Alina Halip, Mădălina Mocanu, Dan Vâță, Andreea Luana Hulubencu, Dragoș Florin Gheucă-Solovăstru, and Laura Gheucă-Solovăstru. 2026. "From Gut Dysbiosis to Skin Inflammation in Atopic Dermatitis: Probiotics and the Gut–Skin Axis—Clinical Outcomes and Microbiome Implications" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010365

APA StyleMicu, A. E., Popescu, I. A., Halip, I. A., Mocanu, M., Vâță, D., Hulubencu, A. L., Gheucă-Solovăstru, D. F., & Gheucă-Solovăstru, L. (2026). From Gut Dysbiosis to Skin Inflammation in Atopic Dermatitis: Probiotics and the Gut–Skin Axis—Clinical Outcomes and Microbiome Implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 365. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010365