Evaluation of NTRK Fusions Detection Method in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Gastric Adenocarcinoma

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

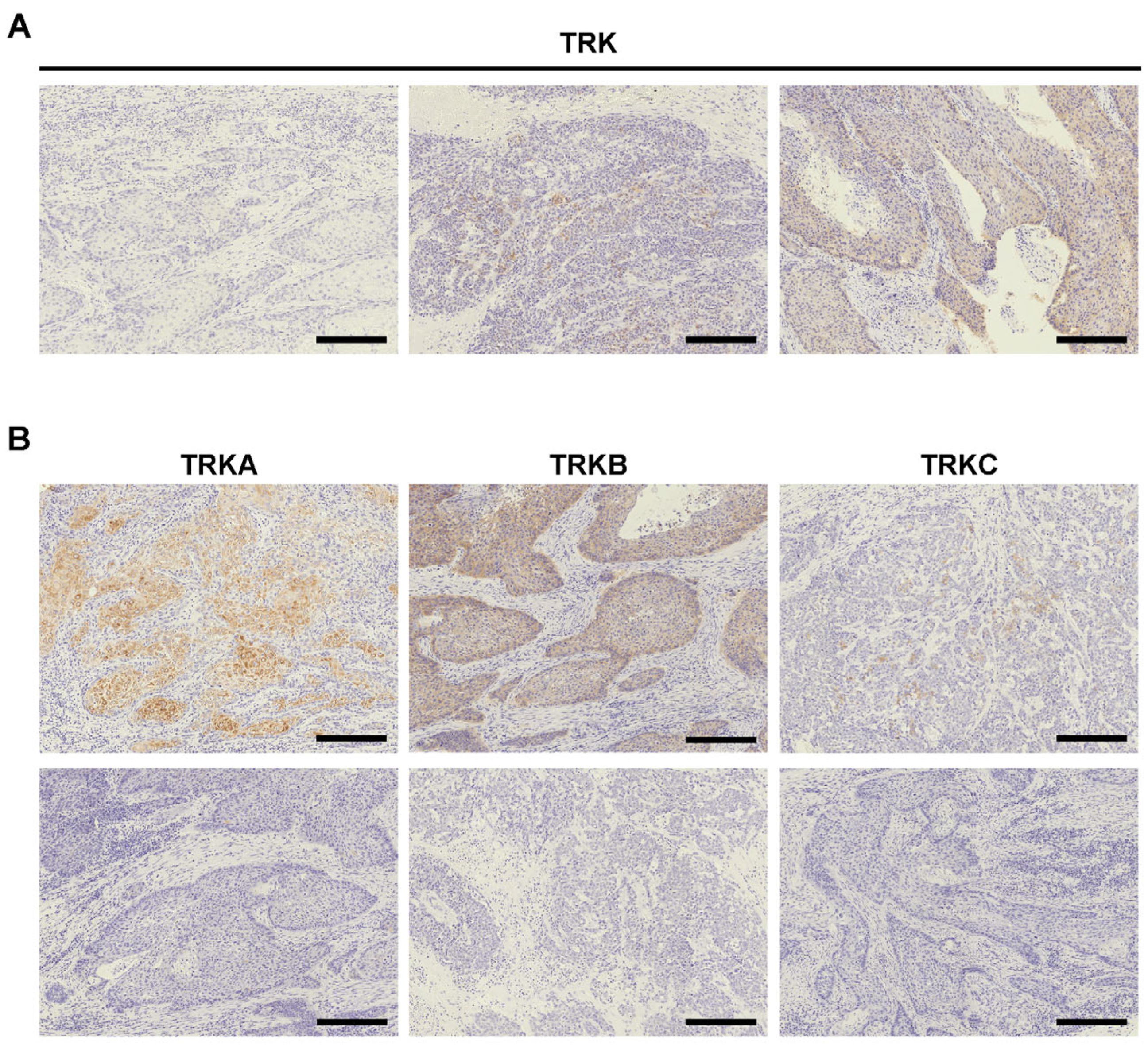

2.1. TRK Expression in ESCC and GA

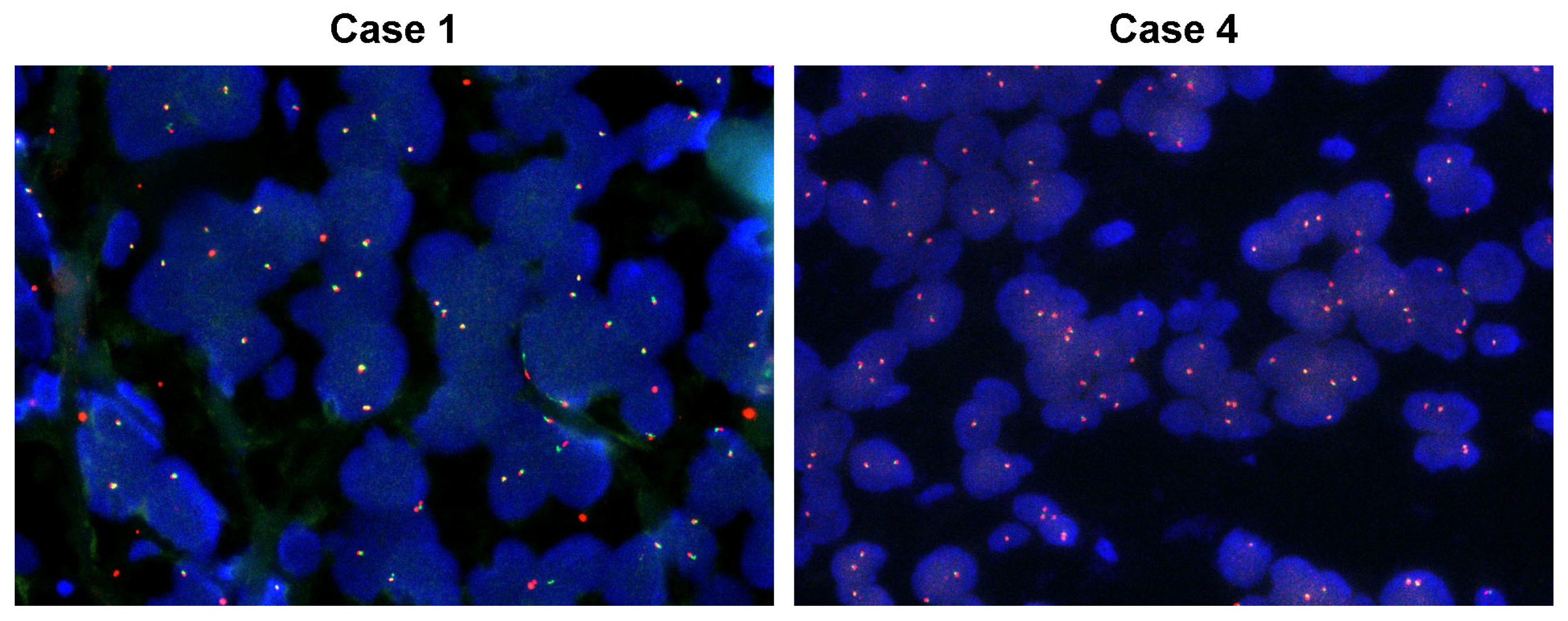

2.2. Confirmation of NTRK Fusion in TRK+ ESCC Cases

2.3. Database NTRK Fusion Detection

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients

4.2. Immunohistochemical Staining and Evaluation

4.3. Next Generation Sequencing

4.4. FISH

4.5. Database Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EBER | Epstein-Barr virus-encoded small RNA |

| EBV | Epstein-Barr virus |

| ESCC | esophageal squamous cell carcinoma |

| FISH | fluorescence in situ hybridization |

| GA | gastric adenocarcinoma |

| IHC | immunohistochemistry |

| NGS | next generation sequencing |

| MMR | mismatch repair |

| NTRK | Neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TKI | tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

References

- Cocco, E.; Scaltriti, M.; Drilon, A. NTRK fusion-positive cancers and TRK inhibitor therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amatu, A.; Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Bencardino, K.; Pizzutilo, E.G.; Tosi, F.; Siena, S. Tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) biology and the role of NTRK gene fusions in cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, viii5–viii15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Shiraishi, K.; Kunitoh, H.; Takenoshita, S.; Yokota, J.; Kohno, T. Gene aberrations for precision medicine against lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drilon, A. TRK inhibitors in TRK fusion-positive cancers. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, viii23–viii30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcus, L.; Donoghue, M.; Aungst, S.; Myers, C.E.; Helms, W.S.; Shen, G.; Zhao, H.; Stephens, O.; Keegan, P.; Pazdur, R. FDA Approval Summary: Entrectinib for the Treatment of NTRK gene Fusion Solid Tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 928–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, Y.; Kurihara, T.; Hayashi, T.; Suehara, Y.; Yao, T.; Kato, S.; Saito, T. NTRK fusion in Japanese colorectal adenocarcinomas. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiq, M.A.; Davis, J.L.; Hornick, J.L.; Dickson, B.C.; Fletcher, C.D.M.; Fletcher, J.A.; Folpe, A.L.; Marino-Enriquez, A. Mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract with NTRK rearrangements: A clinicopathological, immunophenotypic, and molecular study of eight cases, emphasizing their distinction from gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). Mod. Pathol. 2020, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphalen, C.B.; Krebs, M.G.; Le Tourneau, C.; Sokol, E.S.; Maund, S.L.; Wilson, T.R.; Jin, D.X.; Newberg, J.Y.; Fabrizio, D.; Veronese, L.; et al. Genomic context of NTRK1/2/3 fusion-positive tumours from a large real-world population. npj Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5, 69, Correction in npj Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamura, R.; Boichard, A.; Kato, S.; Sicklick, J.K.; Bazhenova, L.; Kurzrock, R. Analysis of NTRK Alterations in Pan-Cancer Adult and Pediatric Malignancies: Implications for NTRK-Targeted Therapeutics. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2018, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchio, C.; Scaltriti, M.; Ladanyi, M.; Iafrate, A.J.; Bibeau, F.; Dietel, M.; Hechtman, J.F.; Troiani, T.; Lopez-Rios, F.; Douillard, J.Y.; et al. ESMO recommendations on the standard methods to detect NTRK fusions in daily practice and clinical research. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1417–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, J.P.; Benayed, R.; Hechtman, J.F.; Ladanyi, M. Identifying patients with NTRK fusion cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, viii16–viii22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, T.; Pentheroudakis, G.; Mishima, S.; Overman, M.J.; Yeh, K.H.; Baba, E.; Naito, Y.; Calvo, F.; Saxena, A.; Chen, L.T.; et al. JSCO-ESMO-ASCO-JSMO-TOS: International expert consensus recommendations for tumour-agnostic treatments in patients with solid tumours with microsatellite instability or NTRK fusions. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, A.; Daum, S.; von Winterfeld, M.; Berg, E.; Hummel, M.; Horst, D.; Rau, B.; Stein, U.; Treese, C. Analysis of NTRK expression in gastric and esophageal adenocarcinoma (AGE) with pan-TRK immunohistochemistry. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2019, 215, 152662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gluckstein, M.I.; Dintner, S.; Miller, S.; Vlasenko, D.; Schenkirsch, G.; Agaimy, A.; Markl, B.; Grosser, B. ALK, NUT, and TRK Do Not Play Relevant Roles in Gastric Cancer-Results of an Immunohistochemical Study in a Large Series. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Shimura, T.; Kitajima, T.; Kondo, S.; Ide, S.; Okugawa, Y.; Saigusa, S.; Toiyama, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Araki, T.; et al. Tropomyosin-related receptor kinase B at the invasive front and tumour cell dedifferentiation in gastric cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 2923–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, A.; Inokuchi, M.; Otsuki, S.; Sugita, H.; Kato, K.; Uetake, H.; Sugihara, K.; Takagi, Y.; Kojima, K. Prognostic value of tropomyosin-related kinases A, B, and C in gastric cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2016, 18, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, H.; Saito, M.; Nakajima, S.; Saito, K.; Nakayama, Y.; Kase, K.; Yamada, L.; Kanke, Y.; Hanayama, H.; Onozawa, H.; et al. PD-L1 overexpression in EBV-positive gastric cancer is caused by unique genomic or epigenomic mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, N.; Kanke, Y.; Saito, K.; Okayama, H.; Yamada, S.; Nakajima, S.; Endo, E.; Kase, K.; Yamada, L.; Nakano, H.; et al. Stromal expression of cancer-associated fibroblast-related molecules, versican and lumican, is strongly associated with worse relapse-free and overall survival times in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, S.; Mimura, K.; Saito, K.; Thar Min, A.K.; Endo, E.; Yamada, L.; Kase, K.; Yamauchi, N.; Matsumoto, T.; Nakano, H.; et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Induces IL34 Signaling and Promotes Chemoresistance via Tumor-Associated Macrophage Polarization in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 2021, 19, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashizawa, M.; Saito, M.; Min, A.K.T.; Ujiie, D.; Saito, K.; Sato, T.; Kikuchi, T.; Okayama, H.; Fujita, S.; Endo, H.; et al. Prognostic role of ARID1A negative expression in gastric cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunami, K.; Ichikawa, H.; Kubo, T.; Kato, M.; Fujiwara, Y.; Shimomura, A.; Koyama, T.; Kakishima, H.; Kitami, M.; Matsushita, H.; et al. Feasibility and utility of a panel testing for 114 cancer-associated genes in a clinical setting: A hospital-based study. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 1480–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, S.J.; Zehir, A.; Sireci, A.N.; Aisner, D.L. Detection of Tumor NTRK Gene Fusions to Identify Patients Who May Benefit from Tyrosine Kinase (TRK) Inhibitor Therapy. J. Mol. Diagn. JMD 2019, 21, 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, J.P.; Linkov, I.; Rosado, A.; Mullaney, K.; Rosen, E.Y.; Frosina, D.; Jungbluth, A.A.; Zehir, A.; Benayed, R.; Drilon, A.; et al. NTRK fusion detection across multiple assays and 33,997 cases: Diagnostic implications and pitfalls. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinozaki-Ushiku, A.; Ishikawa, S.; Komura, D.; Seto, Y.; Aburatani, H.; Ushiku, T. The first case of gastric carcinoma with NTRK rearrangement: Identification of a novel ATP1B-NTRK1 fusion. Gastric Cancer 2020, 23, 944–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Li, G.G.; Kim, S.T.; Hong, M.E.; Jang, J.; Yoon, N.; Ahn, S.M.; Murphy, D.; Christiansen, J.; Wei, G.; et al. NTRK1 rearrangement in colorectal cancer patients: Evidence for actionable target using patient-derived tumor cell line. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 39028–39035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudzinski, E.R.; Lockwood, C.M.; Stohr, B.A.; Vargas, S.O.; Sheridan, R.; Black, J.O.; Rajaram, V.; Laetsch, T.W.; Davis, J.L. Pan-Trk Immunohistochemistry Identifies NTRK Rearrangements in Pediatric Mesenchymal Tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2018, 42, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consortium, A.P.G. AACR Project GENIE: Powering Precision Medicine through an International Consortium. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 818–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014, 513, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasini, L.; Re, A.; Tebaldi, T.; Ricci, G.; Boi, S.; Adami, V.; Barbareschi, M.; Quattrone, A. TrkA is amplified in malignant melanoma patients and induces an anti-proliferative response in cell lines. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | (n = 254) | |

| Age-year | ||

| Mean | 66 | |

| Range | 37–83 | |

| Gender-no. (%) | ||

| Male | 219 (86) | |

| Female | 35 (14) | |

| Race. (%) | ||

| Asian (Japanese) | 254 (100) | |

| Tumor location. (%) | ||

| Upper | 51 (20) | |

| Middle | 130 (51) | |

| Lower | 73 (29) | |

| Histological type-no. (%) | ||

| well | 64 (25) | |

| moderate | 122 (48) | |

| poor | 39 (15) | |

| Unknown | 29 (11) | |

| TNM Stage-no. (%) | ||

| 0 | 32 (13) | |

| I | 43 (17) | |

| II | 85 (33) | |

| III | 82 (32) | |

| IV | 12 (5) | |

| LN metastasis-no. (%) | ||

| Positive | 140 (55) | |

| Negative | 114 (45) | |

| Lymphatic invasion-no. (%) | ||

| Present | 130 (51) | |

| Absent | 124 (49) | |

| Venous invasion-no. (%) | ||

| Present | 144 (57) | |

| Absent | 110 (43) | |

| Total | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | (n = 401) | |

| Age-year | ||

| Mean | 67.7 | |

| Range | 30–92 | |

| Gender-no. (%) | ||

| Male | 283 (71) | |

| Female | 118 (29) | |

| Race. (%) | ||

| Asian (Japanese) | 401 (100) | |

| Tumor location. (%) | ||

| Upper | 128 (32) | |

| Middle | 136 (34) | |

| Lower | 124 (31) | |

| Whole | 6 (1) | |

| N/A | 7 (2) | |

| Histological type-no. (%) | ||

| Differentiated | 208 (52) | |

| Undifferentiated | 193 (48) | |

| TNM Stage-no. (%) | ||

| I | 219 (55) | |

| II | 79 (20) | |

| III | 70 (17) | |

| IV | 33 (8) | |

| LN metastasis-no. (%) | ||

| Positive | 247 (62) | |

| Negative | 154 (38) | |

| Lymphatic invasion-no. (%) | ||

| Present | 218 (54) | |

| Absent | 182 (45) | |

| N/A | 1 (0.2) | |

| Venous invasion-no. (%) | ||

| Present | 228 (57) | |

| Absent | 172 (42) | |

| N/A | 1 (0.2) | |

| Mismatch repair (MMR)-no. (%) | ||

| deficient MMR | 33 (8.2) | |

| proficient MMR | 368 (92) | |

| Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-no. (%) | ||

| Positive | 27 (6.7) | |

| Negative | 374 (93.3) | |

| IHC | NGS | FISH | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case number | TRK (pan-TRK) | TRKA | TRKB | TRKC | NTRK1 fusion | NTRK2 fusion | NTRK3 fusion |

| 1 | ++ | + | + | - | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 2 | ++ | - | - | + | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 3 | ++ | - | + | - | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 4 | + | + | ++ | - | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 5 | + | + | - | - | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 6 | + | - | ++ | - | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 7 | + | - | + | - | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 8 | + | - | + | - | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 9 | + | + | + | - | Failed | Failed | N.D. |

| 10 | + | + | - | - | Failed | Failed | N.D. |

| Control | - | - | - | - | Detected | N.D. | N.D. (NTRK1 fusion detected) |

| Copy Number Alterations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Case number | Mutations | Amplifications | Homozygous deletions |

| 1 | CDKN2A, NFE2L2, PALB2, TP53 | ||

| 2 | TP53 | FGFR1 | CDKN2A, RB1 |

| 3 | NFE2L2, RB1, TP53 | ||

| 4 | NOTCH1, NOTCH3, TP53 | VHL | |

| 5 | KDM6A, PIK3CA, TP53 | MYC | VHL, RHOA, RAD51C |

| 6 | PTCH1, TP53 | ||

| 7 | EP300, PIK3CA, TP53 | RHOA, FLT3 | |

| 8 | NFE2L2, TP53 | ||

| No. of Patients (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Sample | Any NTRK fusions | NTRK1 fusion | NTRK2 fusion | NTRK3 fusion | Detected NTRK fusions | ||

| TCGA study | |||||||

| Esophagogastric cancer (Exclude China Pan-cancer study) | 3/3960 (0.08%) | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Esophagogastric adenocarcinoma | 1/528 (0.19%) | 1 | 0 | 0 | PEAR1-NTRK1, NTRK1-STK11 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction | 1/268 (0.37%) | 1 | 0 | 0 | RRP15-NTRK1 | ||

| Esophageal adenocarcinoma | 1/968 (0.10%) | 1 | 0 | 0 | NAV1-NTRK1 | ||

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | 0/508 (0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | ||

| Gastric adenocarcinoma | 0/1672 (0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | ||

| China Pan-cancer study | |||||||

| Esophageal adenocarcinoma | 0/12 (0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | ||

| Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | 2/582 (0.3%) | 0 | 0 | 2 | NTRK3-NFATC1, NTRK3-SEC11A | ||

| Gastric adenocarcinoma | 7/850 (0.8%) | 1 | 1 | 5 | INSRR1-NTRK1, SLC24A2-NTRK2, LRRC28-NTRK3, LOC100507065-NTRK3, Intergenic-NTRK3, NTRK3-Intergenic | ||

| FoundationCore database | |||||||

| Esophageal cancer | 18/7469 (0.24%) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||

| Gastric cancer | 8/5045 (0.16%) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Momma, T.; Saito, M.; Nakajima, S.; Saito, K.; Machida, E.; Miyabe, K.; Sato, Y.; Hanayama, H.; Okayama, H.; Saze, Z.; et al. Evaluation of NTRK Fusions Detection Method in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010336

Momma T, Saito M, Nakajima S, Saito K, Machida E, Miyabe K, Sato Y, Hanayama H, Okayama H, Saze Z, et al. Evaluation of NTRK Fusions Detection Method in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Gastric Adenocarcinoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010336

Chicago/Turabian StyleMomma, Tomoyuki, Motonobu Saito, Shotaro Nakajima, Katsuharu Saito, Erika Machida, Ken Miyabe, Yusuke Sato, Hiroyuki Hanayama, Hirokazu Okayama, Zenichiro Saze, and et al. 2026. "Evaluation of NTRK Fusions Detection Method in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Gastric Adenocarcinoma" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010336

APA StyleMomma, T., Saito, M., Nakajima, S., Saito, K., Machida, E., Miyabe, K., Sato, Y., Hanayama, H., Okayama, H., Saze, Z., Mimura, K., Tsuchiya, N., Goto, A., Shiraishi, K., & Kono, K. (2026). Evaluation of NTRK Fusions Detection Method in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Gastric Adenocarcinoma. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 336. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010336