Deciphering the Skin Anti-Aging and Hair Growth Promoting Mechanisms of Opophytum forskahlii Seed Oil via Network Pharmacology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. GC-MS Profiling of OFSO

2.2. Skin Antiaging Potential

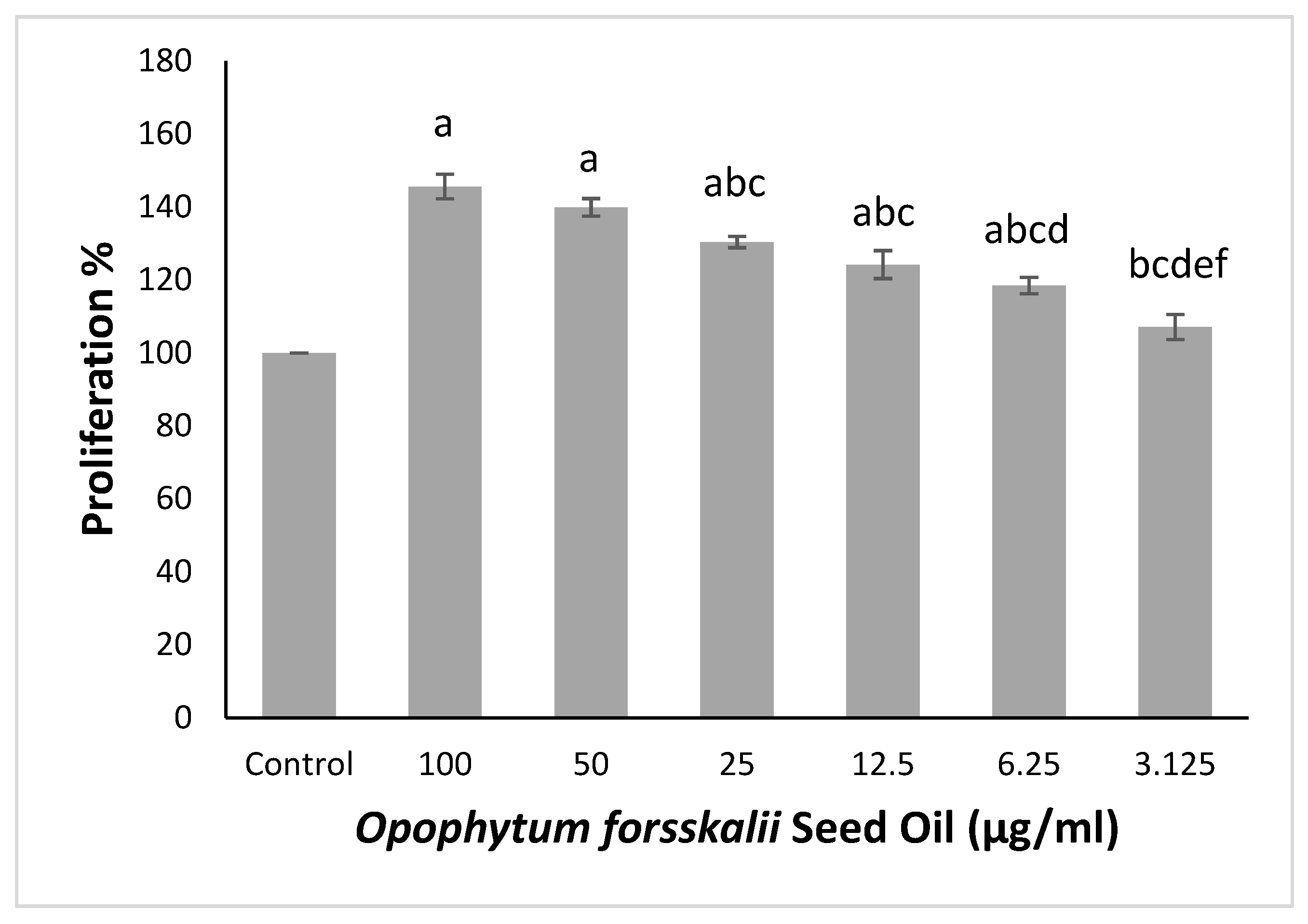

2.2.1. Effect of OFSO on NHDFs Cell Viability

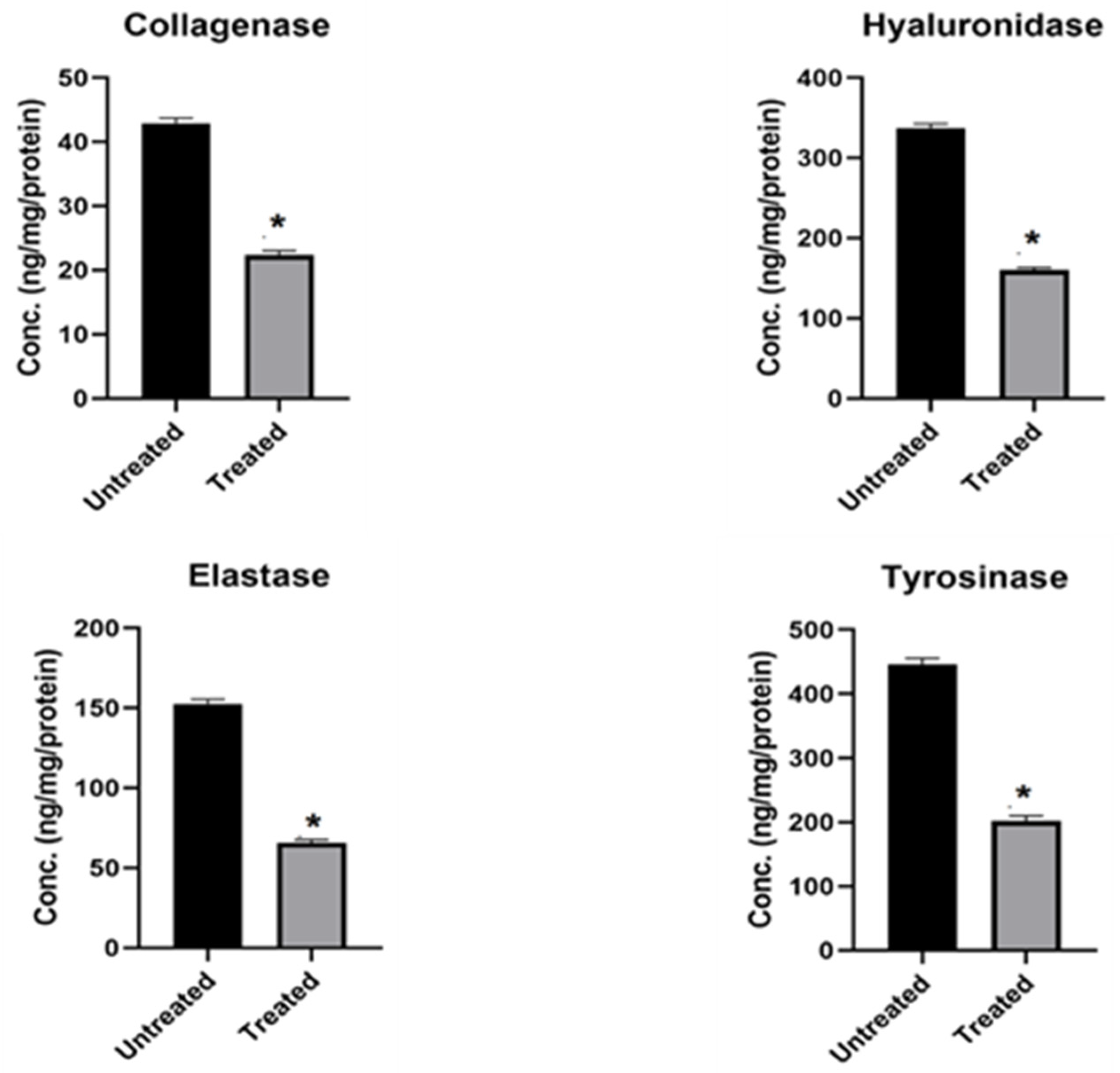

2.2.2. Inhibition of Skin Aging-Related Enzymes

2.2.3. Inhibition of COX1 and COX2 Activity

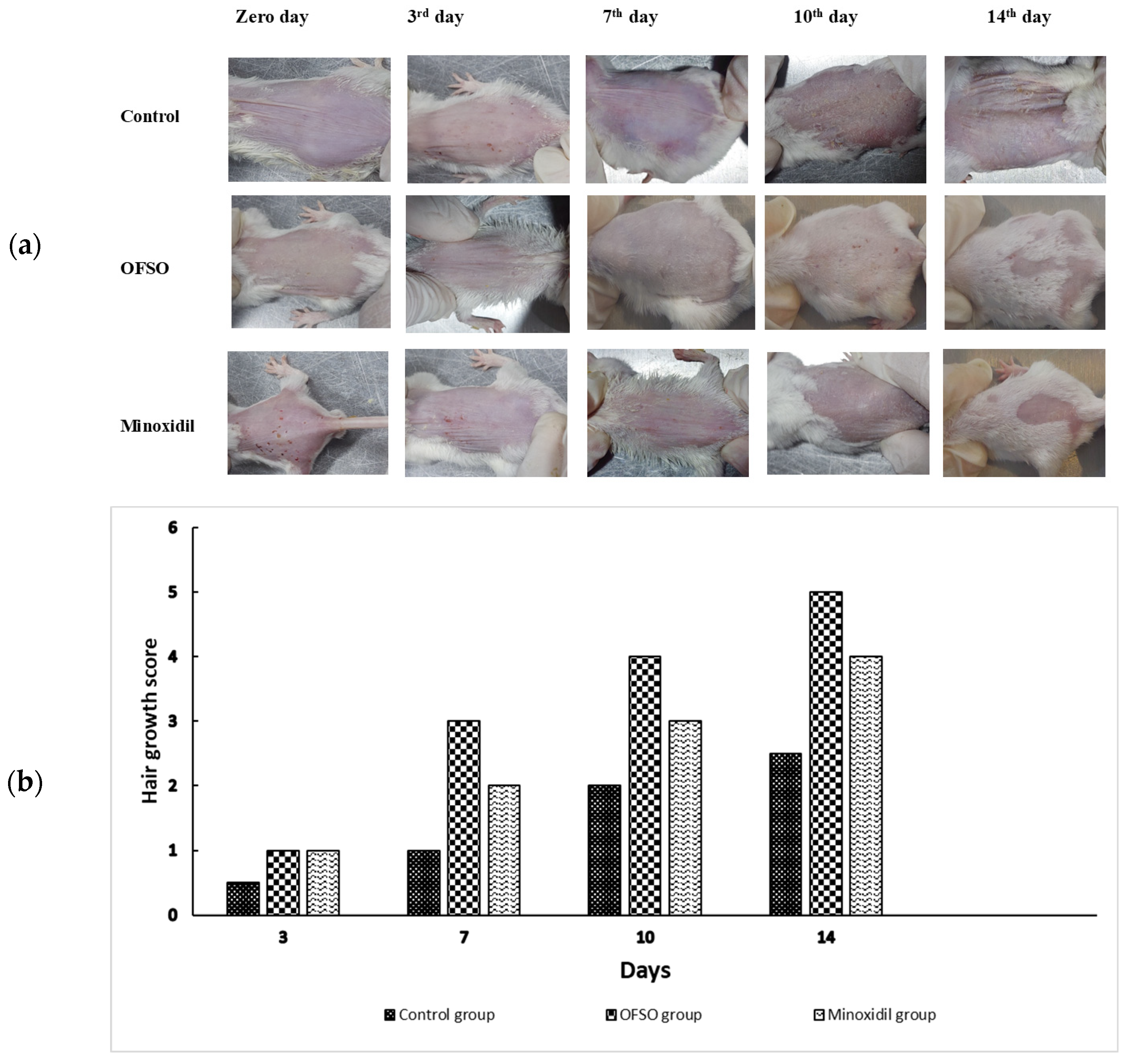

2.3. Effects of OFSO on Hair Growth in Rats

2.3.1. Gross Evaluation of Hair Growth

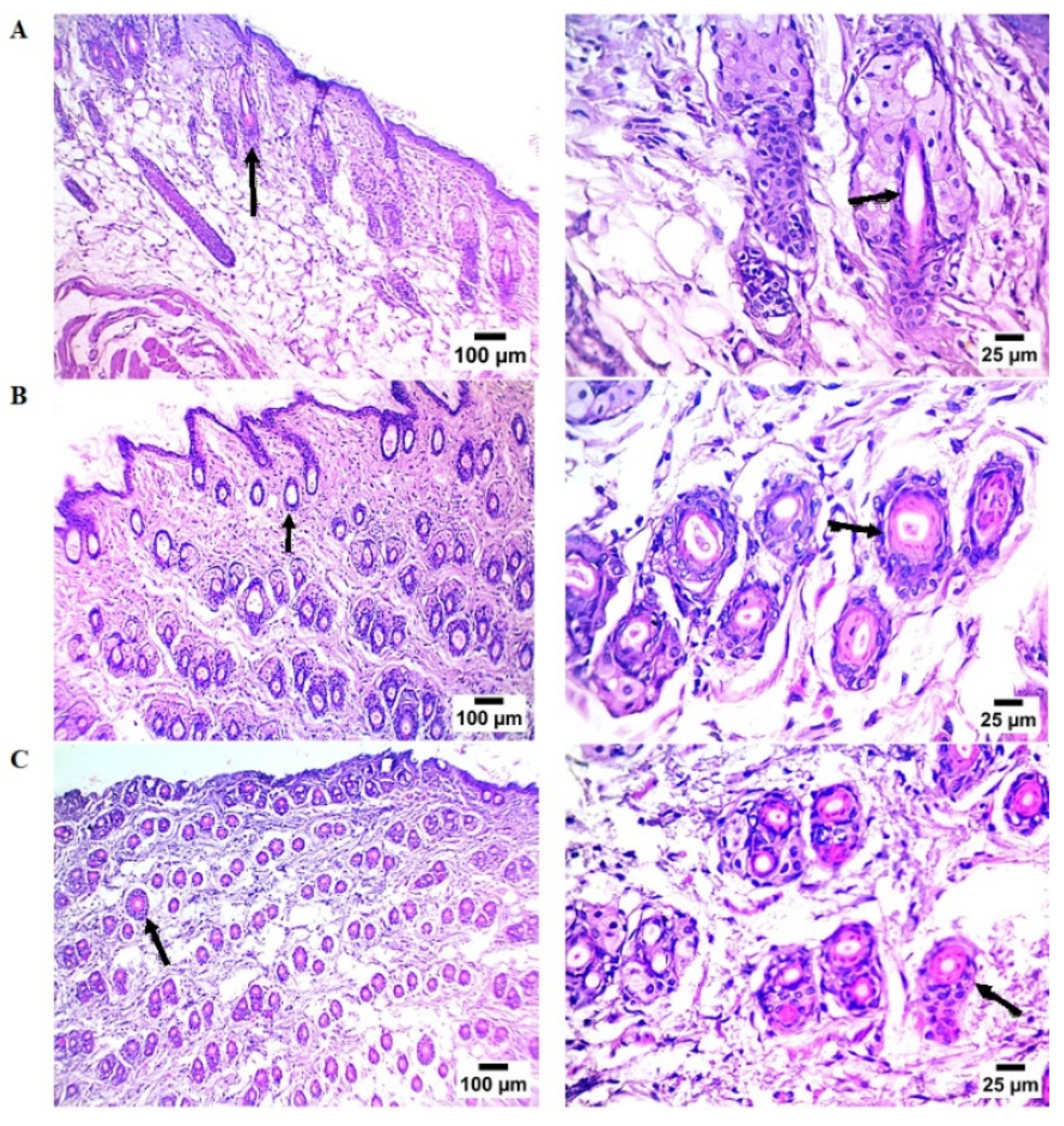

2.3.2. Histopathological Findings

2.4. Network Pharmacology Results

2.4.1. Predicted Target Genes

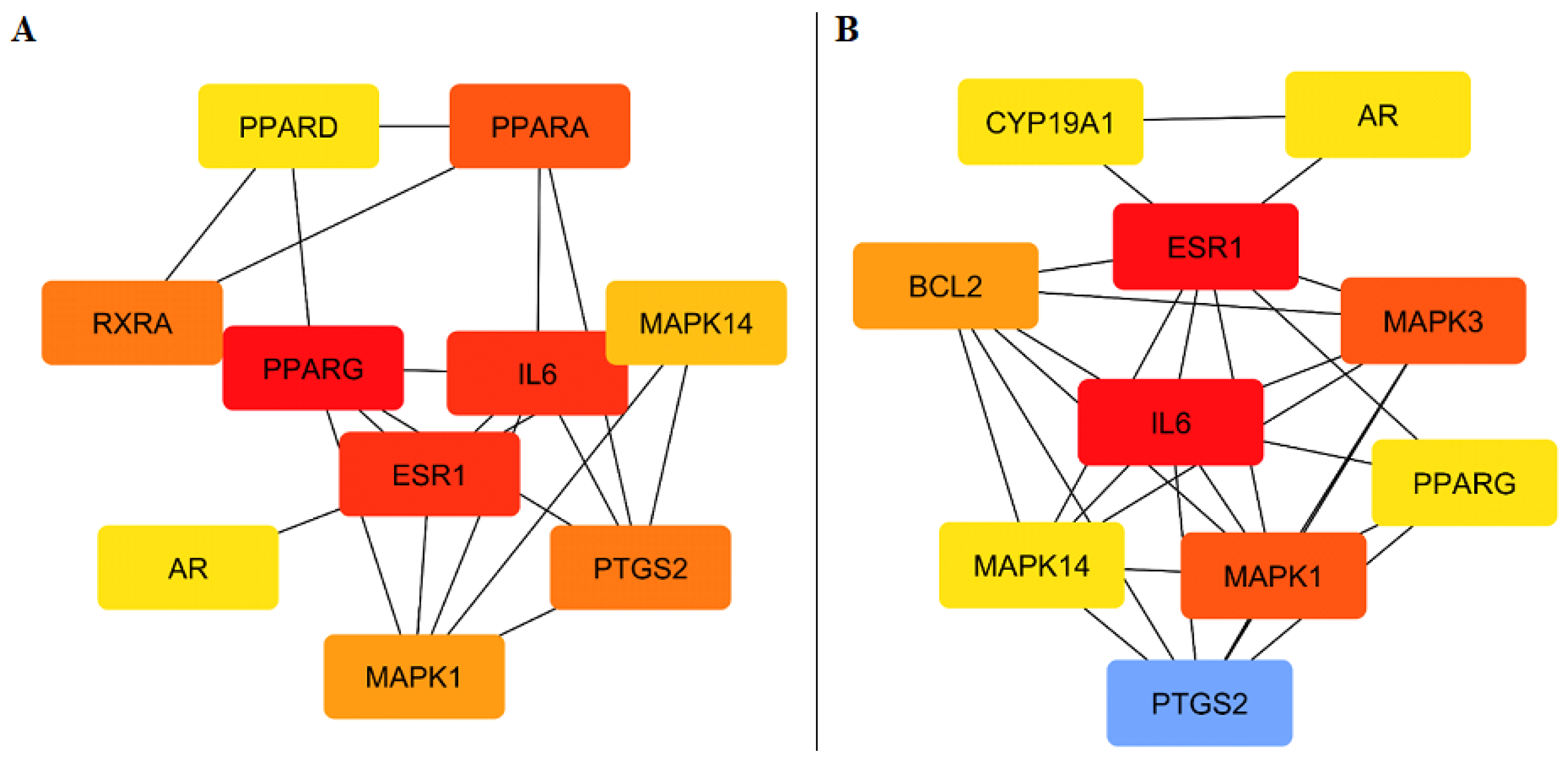

2.4.2. PPI Network and Hub Gene Identification

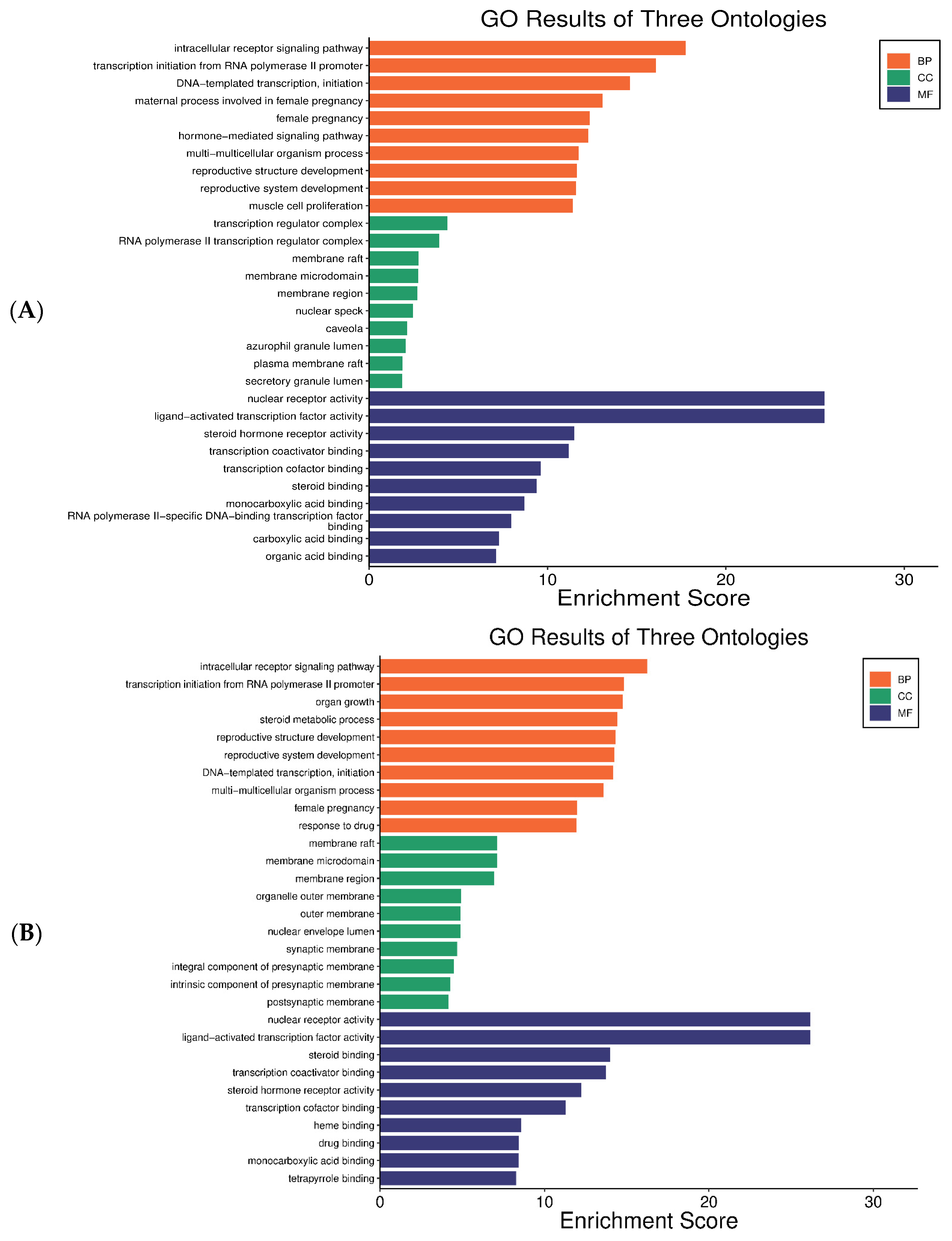

2.4.3. GO Enrichment Analysis

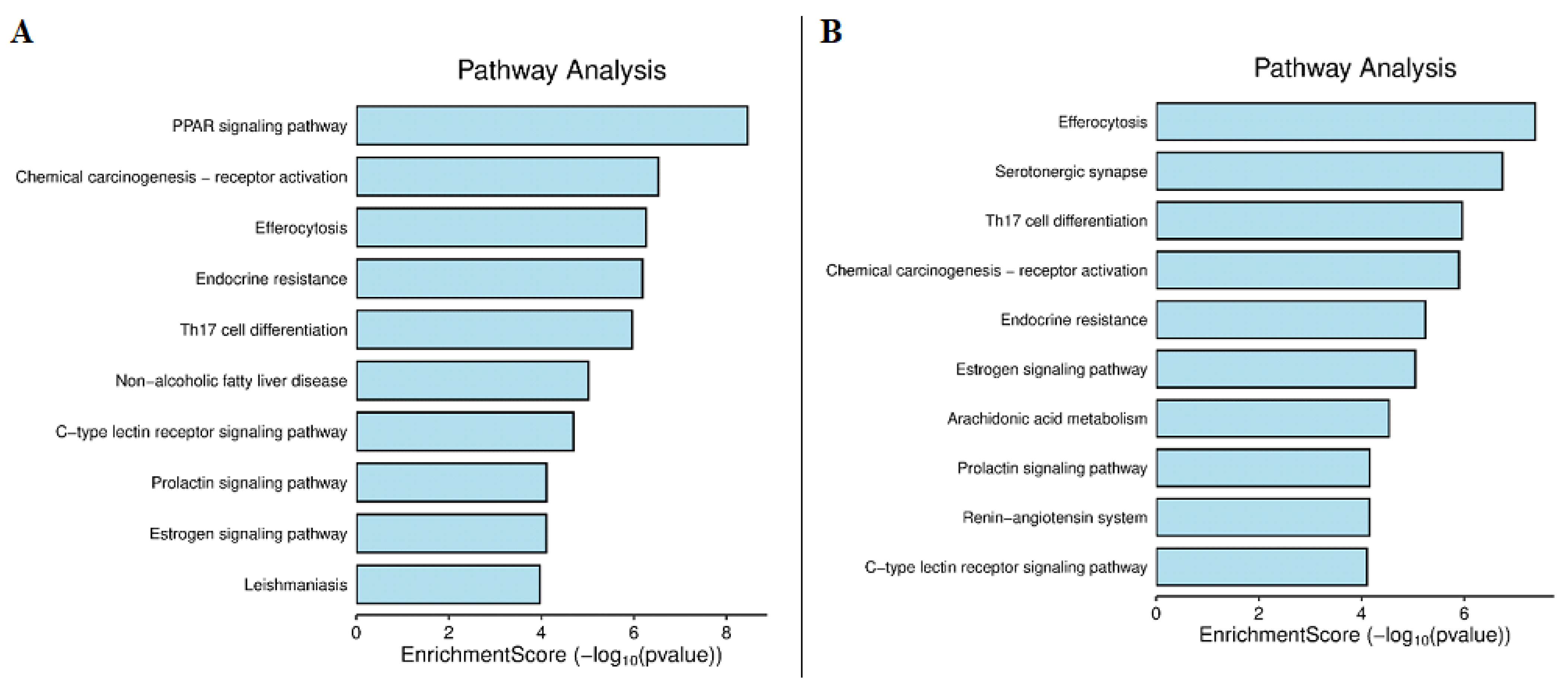

2.4.4. KEGG Pathway Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Preparation of Oil

4.2. Chemicals

4.3. GC-MS Profiling of the Seed Oil

4.4. Skin Anti-Aging Potential

4.4.1. Cell Culture and Treatment

4.4.2. Cell Viability (MTT Assay)

4.4.3. Modulation of Skin Aging-Related Enzymes

4.4.4. Cyclooxygenase (COX1 and COX2) Inhibition Assays

4.5. Hair Growth Promoting Activity

4.5.1. Animals

4.5.2. Experimental Design

4.5.3. Histopathological Study

4.6. Statistical Analysis

4.7. Network Pharmacology Study

4.7.1. Target Gene Prediction

4.7.2. Collection of Disease-Associated Genes

4.7.3. Identification of Overlapping Genes

4.7.4. Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Construction and Hub Gene Analysis

4.7.5. Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COX1 | Cyclooxygenase 1 |

| COX2 | Cyclooxygenase 2 |

| ESR1 | Estrogen Receptor 1 |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| IL6 | Interleukin 6 |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| NHDFs | normal human dermal fibroblasts |

| PPARG | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma. |

References

- Michalak, M. Plant extracts as skin care and therapeutic agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.-K. Natural products in cosmetics. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2022, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trüeb, R.M.; Rezende, H.D.; Dias, M.F.R.G. A comment on the science of hair aging. Int. J. Trichol. 2018, 10, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandaville, J.P. Flora of Eastern Saudi Arabia; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Batanouny, K.H. Plants in the Deserts of the Middle East; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mandaville, J.P. Bedouin Ethnobotany: Plant Concepts and Plant Use in a Desert Pastoral World; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bold, J.; Harris, M.; Fellows, L.; Chouchane, M. Nutrition, the digestive system and immunity in COVID-19. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2020, 13, 331. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaie, A.; Halaji, M.; Dehkordi, F.S.; Ranjbar, R.; Noorbazargan, H. A narrative literature review on traditional medicine options for treatment of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2020, 40, 101214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Faris, N.A.; Al Othman, Z.A.; Ahmad, D. Effects of Mesembrrybryanthemum forsskalei Hochst seeds in lowering glucose/lipid profile in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foudah, A.I.; Aloneizi, F.K.; Alqarni, M.H.; Alam, A.; Salkini, M.A.; Abubaker, H.M.; Yusufoglu, H.S. Potential Active Constituents from Opophytum forsskalii (Hochst. ex Boiss.) N.E.Br against Experimental Gastric Lesions in Rats. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aabed, K.; Mohammed, A.E. Phytoproduct, Arabic Gum and Opophytum forsskalii Seeds for Bio-Fabrication of Silver Nanoparticles: Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Capabilities. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilel, H.; Elsherif, M.A.; Moustafa, S.M.N. Seeds oil extract of Mesembryanthemum forsskalii from Aljouf, Saudi Arabia: Chemical composition, DPPH radical scavenging and antifungal activities. OCL 2020, 27, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.A.M.; Al Juhaimi, F.Y.; Osman, M.A.; Al Maiman, S.A.; Hassan, A.B.; Alqah, H.A.; Babiker, E.E.; Ghafoor, K. Effect of oven roasting treatment on the antioxidant activity, phenolic compounds, fatty acids, minerals, and protein profile of Samh (Mesembryanthemum forsskalei Hochst) seeds. LWT 2020, 131, 109825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Song, B.R.; Kim, J.E.; Bae, S.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, S.J.; Gong, J.E.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, C.Y.; Kim, B.-H.; et al. Therapeutic Effects of Cold-Pressed Perilla Oil Mainly Consisting of Linolenic acid, Oleic Acid and Linoleic Acid on UV-Induced Photoaging in NHDF Cells and SKH-1 Hairless Mice. Molecules 2020, 25, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, A.L. Network pharmacology: The next paradigm in drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008, 4, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.-T.; Lu, Y.; Yan, S.-K.; Xiao, X.; Rong, X.-L.; Guo, J. Network Pharmacology in Research of Chinese Medicine Formula: Methodology, Application and Prospective. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 26, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Jia, Y.; He, H. The Role of Linoleic Acid in Skin and Hair Health: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 26, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichihashi, M.; Yanagi, H.; Yoshimoto, S.; Ando, H.; Kunisada, M.; Nishigori, C. Olive oil and skin aging. Glycative Stress Res. 2018, 5, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, H.S.; Jeong, J.; Lee, C.M.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, J.-N.; Park, S.-M.; Lee, Y.M. Activation of hair cell growth factors by linoleic acid in Malva verticillata seed. Molecules 2021, 26, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, M.; Zhou, J.; Zeng, Z.; Li, S.; Yang, X. Effects of Nannochloropsis salina fermented oil on proliferation of human dermal papilla cells and hair growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.J.; Wang, B.; Cui, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhao, Y.; Quan, T.; Voorhees, J.J. Skin aging from the perspective of dermal fibroblasts: The interplay between the adaptation to the extracellular matrix microenvironment and cell autonomous processes. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 17, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.A.; Quan, T.; Voorhees, J.J.; Fisher, G.J. Extracellular matrix regulation of fibroblast function: Redefining our perspective on skin aging. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018, 12, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jipu, R.; Serban, I.L.; Goriuc, A.; Jipu, A.G.; Luchian, I.; Amititeloaie, C.; Tarniceriu, C.C.; Hurjui, I.; Butnaru, O.M.; Hurjui, L.L. Targeting Dermal Fibroblast Senescence: From Cellular Plasticity to Anti-Aging Therapies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, M.; Günal-Köroğlu, D.; Kamiloglu, S.; Ozdal, T.; Capanoglu, E. The state of the art in anti-aging: Plant-based phytochemicals for skin care. Immun. Ageing 2025, 22, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haoran, W.; Jinyv, Z.; Shikui, C.; Jingwei, L. Research on the mechanisms of plant bioactive metabolites in anti-skin aging and future development prospects. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1673075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choy, Y.-J.; Kim, G.-R.; Baik, H.-U. Inhibitory Effects of Naringenin on LPS-Induced Skin Inflammation by NF-κB Regulation in Human Dermal Fibroblasts. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 9245–9254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Tang, G.; Li, X.; Sun, W.; Liang, Y.; Gan, D.; Liu, G.; Song, W.; Wang, Z. Study on the chemical constituents of nut oil from Prunus mira Koehne and the mechanism of promoting hair growth. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 258, 112831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Seo, H.D.; Kim, D.; Park, S.H.; Kim, S.R.; Hyun, C.; Hahm, J.H.; Ha, T.Y.; Ahn, J.; Jung, C.H. Millet seed oil activates β–catenin signaling and promotes hair growth. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1172084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuth, M.; Moosbrugger-Martinz, V.; Blunder, S.; Dubrac, S. Role of PPAR, LXR, and PXR in epidermal homeostasis and inflammation. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2014, 1841, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramot, Y.; Bertolini, M.; Boboljova, M.; Uchida, Y.; Paus, R. PPAR-γ signalling as a key mediator of human hair follicle physiology and pathology. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lephart, E.D.; Naftolin, F. Factors Influencing Skin Aging and the Important Role of Estrogens and Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs). Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 1695–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.-S.; Smart, R.C. An estrogen receptor pathway regulates the telogen-anagen hair follicle transition and influences epidermal cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 12525–12530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, M.; Brincat, S.; Camilleri, G.; Schembri-Wismayer, P.; Brincat, M.; Calleja-Agius, J. The role of cytokines in skin aging. Climacteric 2013, 16, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, A.; Ogawa, Y.; Takemoto, T.; Wang, Y.; Furukawa, T.; Kono, H.; Adachid, Y.; Kusumoto, K. Interleukin 6 induces the hair follicle growth phase (anagen). J. Dermatol. Sci. 2006, 43, 210–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAT Bioquest Inc. IC50 Calculator. 2025. Available online: https://www.aatbio.com/tools/ic50-calculator (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Magalhaes, J.; Lamas, S.; Portinha, C.; Logarinho, E. Optimized Depilation Method and Comparative Analysis of Hair Growth Cycle in Mouse Strains. Animals 2024, 14, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bancroft, J.D.; Gamble, M. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques, 6th ed.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Peak | Rt * (min.) | Component | Formula | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14.76 | Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | C17H34O2 | 5.58 |

| 2 | 16.328 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)-, methyl ester (Linoleic acid) | C19H34O2 | 55.46 |

| 3 | 16.387 | 9-Octadecenoic acid (Z)-, methyl ester (Oleic acid) | C19H36O2 | 38.54 |

| 4 | 16.714 | Cyclopropanebutanoic acid, 2-[[2-[[2-[(2-pentylcyclopropyl)methyl]cyclopropyl]methyl]cyclopropyl]methyl]-, methyl ester | C25H42O2 | 0.41 |

| Groups | Hair Follicle Count * |

|---|---|

| Control | 3.6 ± 0.93 |

| OFSO | 14.0 ± 1.00 a |

| Minoxidil | 9.2 ± 0.80 a,b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ahmed, S.R.; Khojah, H.; Aldera, M.; Alsarah, J.; Alwaghid, D.; Hamdan, L.; Aljuwair, H.; Alshammari, M.; Albalawi, H.; Aldekhail, R.; et al. Deciphering the Skin Anti-Aging and Hair Growth Promoting Mechanisms of Opophytum forskahlii Seed Oil via Network Pharmacology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010277

Ahmed SR, Khojah H, Aldera M, Alsarah J, Alwaghid D, Hamdan L, Aljuwair H, Alshammari M, Albalawi H, Aldekhail R, et al. Deciphering the Skin Anti-Aging and Hair Growth Promoting Mechanisms of Opophytum forskahlii Seed Oil via Network Pharmacology. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010277

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed, Shaimaa R., Hanan Khojah, Maram Aldera, Jenan Alsarah, Dai Alwaghid, Luluh Hamdan, Hadeel Aljuwair, Manal Alshammari, Hanadi Albalawi, Reema Aldekhail, and et al. 2026. "Deciphering the Skin Anti-Aging and Hair Growth Promoting Mechanisms of Opophytum forskahlii Seed Oil via Network Pharmacology" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010277

APA StyleAhmed, S. R., Khojah, H., Aldera, M., Alsarah, J., Alwaghid, D., Hamdan, L., Aljuwair, H., Alshammari, M., Albalawi, H., Aldekhail, R., Alazmi, A., & Qasim, S. (2026). Deciphering the Skin Anti-Aging and Hair Growth Promoting Mechanisms of Opophytum forskahlii Seed Oil via Network Pharmacology. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010277