Anti-Aging Efficacy of Low-Molecular-Weight Polydeoxyribonucleotide Derived from Paeonia lactiflora

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Peony PDRN Is Isolated from P. lactiflora and Fractionated into Different Molecular Sizes

2.2. Peony PDRN Enhances Proliferation of the Human Skin Cells

2.3. Peony PDRN Enhances the Migration of Human Skin Cells

2.4. Peony PDRN Enhances Expression of Genes Related to Keratinocyte Differentiation and Those Encoding ECM Proteins

2.5. Low-Peony PDRN Restores Keratinocyte Differentiation and ECM-Related Gene Expression Suppressed by UV Irradiation

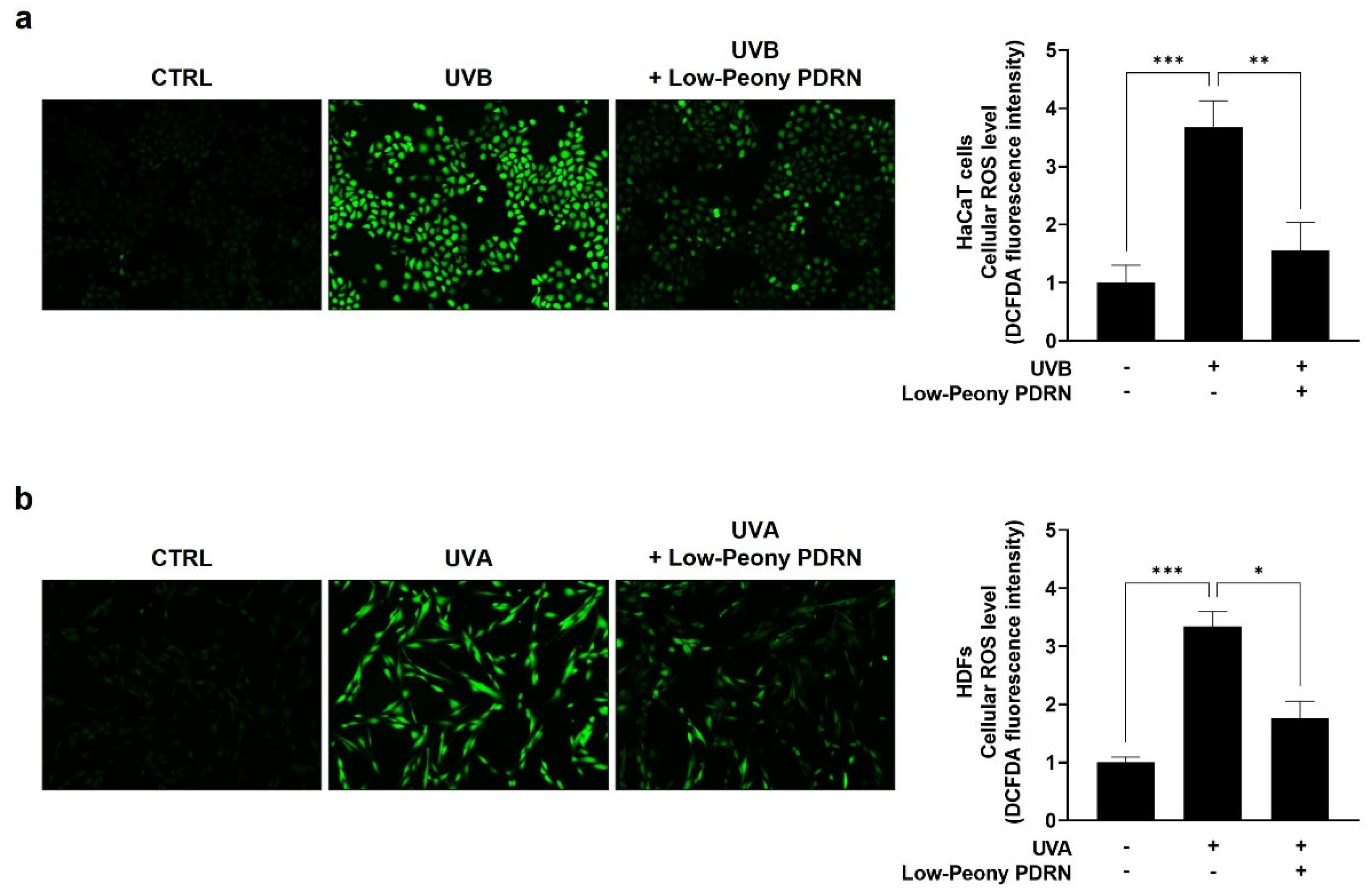

2.6. Low-Peony PDRN Attenuates UV-Induced Oxidative Stress by Reducing Intracellular ROS Levels in Human Skin Cells

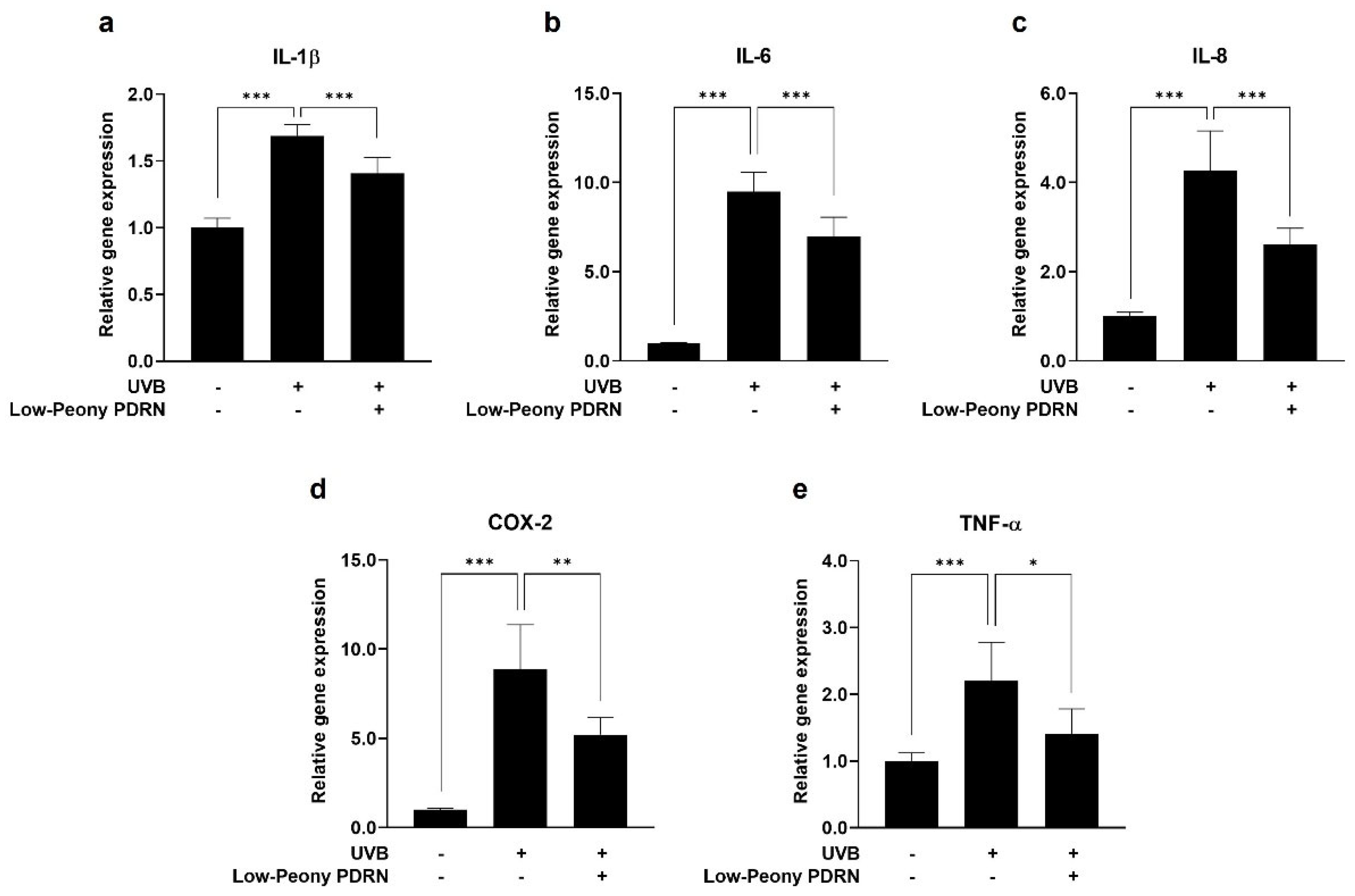

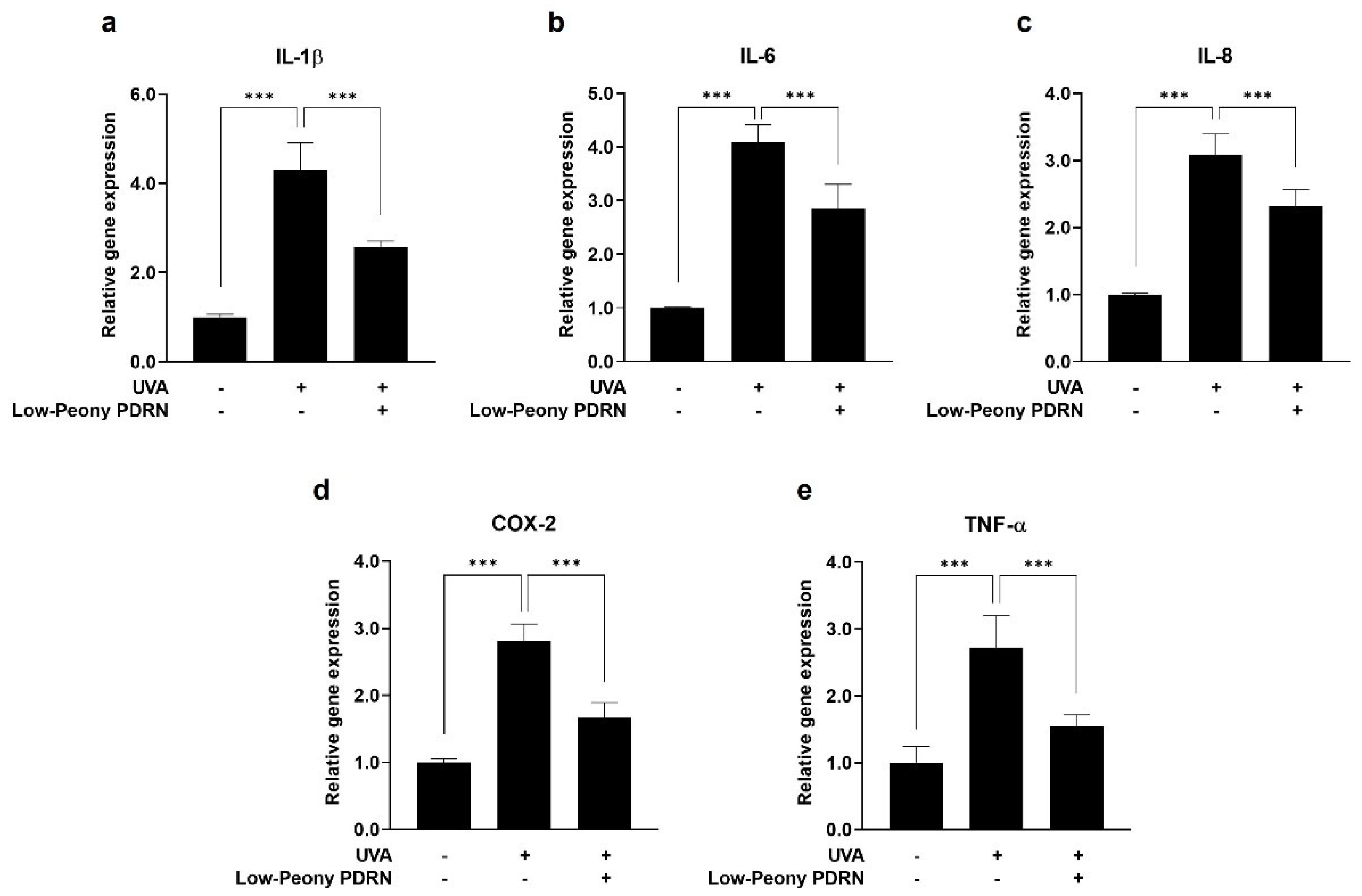

2.7. Low-Peony PDRN Attenuates UV-Induced Upregulation of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Human Skin Cells

2.8. Low-Peony PDRN Improves Periorbital Skin Elasticity

2.9. Low-Peony PDRN Improves TEWL Recovery After Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (SLS)-Induced Barrier Disruption

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Isolation of PDRN from P. lactiflora

4.2. Cell Culture

4.3. Cell Proliferation Assay

4.4. Scratched Wound Healing Assay

4.5. Real-Time Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

4.6. UVA/UVB Irradiation

4.7. Measurement of Intracellular ROS Levels

4.8. Clinical Study Design

4.9. Clinical Evaluation Procedures

4.10. Measurement of Skin Elasticity

4.11. Measurement of TEWL

4.12. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COL1A1 | Collagen, type I, alpha 1 |

| COL5A1 | Collagen, type V, alpha 1 |

| COL7A1 | Collagen, type VII alpha 1 |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| DCF-DA | 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate |

| DEJ | Dermal-epidermal junction |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ELN | Elastin |

| FBN1 | Fibrillin1 |

| FLG | Filaggrin |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| HaCaT cells | Human keratinocytes |

| HDFs | Human dermal fibroblasts |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| IVL | Involucrin |

| OCLN | Occludin |

| PDRN | Polydeoxyribonucleotide |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SLS | Sodium lauryl sulfate |

| TEWL | Transepidermal water loss |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| WST | Water-soluble tetrazolium salt |

References

- Shin, J.W.; Kwon, S.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Na, J.I.; Huh, C.-H.; Choi, H.R.; Park, K.C. Molecular mechanisms of dermal aging and antiaging approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.H. Aging of the skin barrier. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 37, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, G.J.; Wang, B.; Cui, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhao, Y.; Quan, T.; Voorhees, J.J. Skin aging from the perspective of dermal fibroblasts: The interplay between the adaptation to the extracellular matrix microenvironment and cell autonomous processes. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 17, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, T. Molecular insights of human skin epidermal and dermal aging. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2023, 112, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutmann, J. Ultraviolet A radiation-induced biological effects in human skin: Relevance for photoaging and photodermatosis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2000, 23, S22–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.C.; Hill, R.C.; Calderone, K.; Cui, Y.; Yan, Y.; Quan, T.; Fisher, G.J.; Hansen, K.C. Alterations in extracellular matrix composition during aging and photoaging of the skin. Matrix Biol. Plus 2020, 8, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocheva, G.; Slominski, R.M.; Slominski, A.T. Environmental air pollutants affecting skin functions with systemic implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, M.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Tran, K.; Reddy, S.P.; Malik, A.B. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 1126–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, H.M.; Lee, S.; Hong, S.; Lee, S.; Jung, K.; Kang, K.S. Protective effect of polymethoxyflavones isolated from Kaempferia parviflora against TNF-α-induced human dermal fibroblast damage. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, M.; Qin, X.; Yu, X.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Li, W. COX-2 is required to mediate crosstalk of ROS-dependent activation of MAPK/NF-κB signaling with pro-inflammatory response and defense-related NO enhancement during challenge of macrophage-like cell line with Giardia duodenalis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Han, X.; Zhang, T.; Tian, K.; Li, Z.; Luo, F. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging biomaterials for anti-inflammatory diseases: From mechanism to therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gęgotek, A.; Łuczaj, W.; Skrzydlewska, E. Effects of natural antioxidants on phospholipid and ceramide profiles of 3D-cultured skin fibroblasts exposed to UVA or UVB radiation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Zhu, S.; Yang, Y.; Qin, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Duan, T.; Liu, Y.; et al. Oroxylin A ameliorates ultraviolet radiation-induced premature skin aging by regulating oxidative stress via the Sirt1 pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 171, 116110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theocharis, A.D.; Skandalis, S.S.; Gialeli, C.; Karamanos, N.K. Extracellular matrix structure. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 97, 4–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanos, N.K.; Theocharis, A.D.; Piperigkou, Z.; Manou, D.; Passi, A.; Skandalis, S.S.; Vynios, D.H.; Orian-Rousseau, V.; Ricard-Blum, S.; Schmelzer, C.E.H.; et al. A guide to the composition and functions of the extracellular matrix. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 6850–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.N.A.; Irvine, A.D.; Terron-Kwiatkowski, A.; Zhao, Y.; Liao, H.; Lee, S.P.; Goudie, D.R.; Sandilands, A.; Campbell, L.E.; Smith, F.J.D.; et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Woodfolk, J.A. Skin barrier defects in atopic dermatitis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014, 14, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Man, M.Q.; Li, T.; Elias, P.M.; Mauro, T.M. Aging-associated alterations in epidermal function and their clinical significance. Aging 2020, 12, 5551–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano, M.; Pallio, G.; Irrera, N.; Mannino, F.; Bitto, A.; Altavilla, D.; Vaccaro, M.; Squadrito, G.; Arcoraci, V.; Colonna, M.R.; et al. Polydeoxyribonucleotide: A promising biological platform to accelerate impaired skin wound healing. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, H.J.; Jang, H.-J.; Park, H.; Kim, G.J. Human placenta MSC-derived DNA fragments exert therapeutic effects in a skin wound model via the A2A receptor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, Y.; Yun, Y. Effects of polydeoxyribonucleotides (PDRN) on wound healing: Electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS). Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2016, 69, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picciolo, G.; Mannino, F.; Irrera, N.; Altavilla, D.; Minutoli, L.; Vaccaro, M.; Arcoraci, V.; Squadrito, V.; Picciolo, G.; Squadrito, F.; et al. PDRN, a natural bioactive compound, blunts inflammation and positively reprograms healing genes in an “in vitro” model of oral mucositis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.M.; Baek, E.J.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, K.J.; Park, E.J. Polydeoxyribonucleotide exerts opposing effects on ERK activity in human skin keratinocytes and fibroblasts. Mol. Med. Rep. 2023, 28, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, A.; Baek, D.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, J.; Notario, G.R.; Lee, D.W.; Kim, H.J.; Cho, S.R. Polydeoxyribonucleotide ameliorates IL-1β-induced impairment of chondrogenic differentiation in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.M.; Nam, G.B.; Lee, E.S.; Kim, H.M.; Kim, H.; Myoung, K.; Lee, J.E.; Baek, H.S.; Ko, J.; Lee, C.S. Effects of Chlorella protothecoides-derived polydeoxyribonucleotides on skin regeneration and wound healing. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2025, 317, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squadrito, F.; Bitto, A.; Irrera, N.; Pizzino, G.; Pallio, G.; Minutoli, L.; Altavilla, D. Pharmacological activity and clinical use of PDRN. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 224, Erratum in Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1073510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-S.; Lee, S.; Wang, H.; Lee, G.; Kim, S.; Ryu, Y.-H.; Chang, N.H.; Kang, Y.-W. Analysis of skin regeneration and barrier-improvement efficacy of polydeoxyribonucleotide isolated from Panax ginseng (C.A. Mey.) adventitious root. Molecules 2023, 28, 7240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; Porcello, A.; Cerrano, M.; Hadjab, F.; Chemali, M.; Lourenço, K.; Hadjab, B.; Raffoul, W.; Applegate, L.A.; Laurent, A.E. From polydeoxyribonucleotides (PDRNs) to polynucleotides (PNs): Bridging the gap between scientific definitions, molecular insights, and clinical applications of multifunctional biomolecules. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.H.; Seo, H.H.; Shin, D.S.; Song, J.H.; Yun, S.K.; Lee, J.H.; Moh, S.H. Safety Validation of Plant-Derived Materials for Skin Application. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavagnino, A.; Azadiguian, G.; Breton, L.; Baraibar, M.; Black, A.F. Modulating Skin Aging Molecular Targets and Longevity Drivers Through a Novel Natural Product: Rose-Derived Polydeoxyribonucleotide (Rose PDRN). Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.Y.; Dai, S.M. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of Paeonia lactiflora pall., a traditional Chinese herbal medicine. Front. Pharmacol. 2011, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Ren, H.; Meng, X.; Liu, S.; Du, K.; Fang, S.; Chang, Y. A review of the ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and quality control of Paeonia lactiflora pall. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 335, 118616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.-R.; Choi, D.-K.; Sohn, K.-C.; Lim, S.K.; Kim, D.-I.; Lee, Y.H.; Im, M.; Lee, Y.; Seo, Y.-J.; Kim, C.D.; et al. Inhibitory effect of Paeonia lactiflora pallas extract (PE) on poly (I:C)-induced immune response of epidermal keratinocytes. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 5236–5241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Li, T.; Li, B.; Sun, S. Skin health properties of Paeonia lactiflora flower extracts and tyrosinase inhibitors and free radical scavengers identified by HPLC post-column bioactivity assays. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.-L.; Wang, W.; Rashed, M.M.A.; Duan, H.; Li, L.-L.; Zhai, K.-F. Exploring the anti-skin inflammation substances and mechanism of Paeonia lactiflora pall. flower via network pharmacology-HPLC integration. Phytomedicine 2024, 129, 155565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, R.; Kang, S.-G.; Huang, K.; Tong, T. α-Ionone protects against UVB-induced photoaging in epidermal keratinocytes. Chin. Herb. Med. 2022, 15, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, N.-Y.; Choi, S.-H.; Oh, C.-H.; Won, G.-W.; Bhatta, M.P.; Moon, J.H.; Lee, C.-G.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.-L.; et al. Molecular mechanism of the anti-inflammatory and skin protective effects of Syzygium formosum in human skin keratinocytes. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 33, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, I.J.; Yoo, H.; Paik, S.H.; Kim, H.T.; Kim, S.Y.; Song, Y.; Chang, S.E. Ursodeoxycholic Acid May Inhibit Environmental Aging-Associated Hyperpigmentation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolosik, K.; Chalecka, M.; Palka, J.; Surazynski, A. Protective Effect of Amaranthus cruentus L. Seed Oil on UVA-Radiation-Induced Apoptosis in Human Skin Fibroblasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.S.; Jeong, C.O. Cosmetic Composition Containing Polydeoxyribonucleotide. Korean Patent No. KR101722181, 27 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, D.; Oh, S.-W.; Choi, Y.-S.; Kang, D.-J.; Park, C.-W.; Lee, J.; Seo, W.-S. First report on microbial-derived polydeoxyribonucleotide: A sustainable and enhanced alternative to salmon-based polydeoxyribonucleotide. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Park, E.Y.; Cha, S.-K. An effective range of polydeoxyribonucleotides is critical for wound healing quality. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 5166–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essendoubi, M.; Gobinet, C.; Reynaud, R.; Angiboust, J.F.; Manfait, M.; Piot, O. Human skin penetration of hyaluronic acid of different molecular weights as probed by Raman spectroscopy. Skin Res. Technol. 2016, 22, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farwick, M.; Gauglitz, G.; Pavicic, T.; Köhler, T.; Wegmann, M.; Schwach-Abdellaoui, K.; Malle, B.; Tarabin, V.; Schmitz, G.; Korting, H.C. Fifty-kDa hyaluronic acid upregulates some epidermal genes without changing TNF-α expression in reconstituted epidermis. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2011, 24, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakrewsky, M.; Kumar, S.; Mitragotri, S. Nucleic acid delivery into skin for the treatment of skin disease: Proofs-of-concept, potential impact, and remaining challenges. J. Control. Release 2015, 219, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokudome, Y.; Komi, T.; Omata, A.; Sekita, M. A new strategy for the passive skin delivery of nanoparticulate, high molecular weight hyaluronic acid prepared by a polyion complex method. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhaščik, M.; Kováčik, A.; Huerta-Ángeles, G. Recent advances of hyaluronan for skin delivery: From structure to fabrication strategies and applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akl, M.A.; Eldeen, M.A.; Kassem, A.M. Beyond skin deep: Phospholipid-based nanovesicles as game-changers in transdermal drug delivery. AAPS PharmSciTech 2024, 25, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.Y.; Kim, M.H. Preparation Method of High-Purity Plant-Derived PDRN with Excellent Storage Stability and Composition for Anti-Inflammation, Skin Regeneration and Wound Healing Containing the Same. Korean Patent No. KR102707680, 11 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Basselet, P.; Wegrzyn, G.; Enfors, S.O.; Gabig-Ciminska, M. Sample processing for DNA chip array-based analysis of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC). Microb. Cell Factories 2008, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, N.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, S.; Lim, I. Combination of 131I-trastuzumab and lanatoside C enhanced therapeutic efficacy in HER2 positive tumor model. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.-M.; Park, W.-J.; Kim, M.K.; Baek, K.J.; Kwon, N.S.; Yun, H.Y.; Kim, D.-S. Leucine-rich glioma inactivated 3 promotes HaCaT keratinocyte migration. Wound Repair Regen. 2013, 21, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, R.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; Yue, C.; Tan, Y.; Li, L.; Lei, X. Dermal fibroblast migration and proliferation upon wounding or lipopolysaccharide exposure is mediated by stathmin. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 781282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.; Mônico, D.A.; Tedesco, A.C. Implications of dichlorofluorescein photoinstability for detection of UVA-induced oxidative stress in fibroblasts and keratinocyte cells. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2020, 19, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, M.; Kim, Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, B. Natural illite liquid mineral extract: A clinical study of an emulsion to improve skin barrier function. Minerals 2024, 14, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Group | Measurement (M ± SD) | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 2 Weeks | 4 Weeks | Baseline-2 Weeks | Baseline-4 Weeks | ||

| R2 | Control (n = 10) | 69.36 ± 8.02 | 69.57 ± 8.17 | 69.59 ± 8.60 | - | - |

| Experimental (n = 10) | 69.22 ± 7.91 | 69.71 ± 7.93 | 72.16 ± 8.24 | - | 0.000 *** | |

| Group | TEWL (M ± SD) | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before SLS | After SLS | 1 Week | 2 Weeks | 1 Week After SLS | 2 Weeks After SLS | |

| Control (n = 10) | 12.96 ± 1.45 | 16.58 ± 1.58 | 15.15 ± 1.17 | 14.21 ± 1.09 | 0.008 ** | 0.002 ** |

| Experimental (n = 10) | 12.80 ± 1.67 | 17.27 ± 1.93 | 14.93 ± 1.66 | 13.60 ± 1.48 | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** |

| Time Point (vs. After SLS) | Reduction Rate (%) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 10) | Experimental (n = 10) | ||

| 1 week | 8.40 | 13.43 | 0.035 * |

| 2 weeks | 13.98 | 21.01 | 0.026 * |

| Gene Name | Primer Sequence (5′ → 3′) | |

|---|---|---|

| COL1A1 | Forward | CAT AAA GGG TCA CCG TGG CT |

| Reverse | GGG ACC TTG TTC ACC AGG AG | |

| COL5A1 | Forward | ACC ACC AAA TTC CTC GAC C |

| Reverse | CCT CAA ACA CCT CCT CAT CC | |

| COL7A1 | Forward | GTT GGA GAG AAA GGT GAC GAG G |

| Reverse | TGG TCT CCC TTT TCA CCC ACA G | |

| ELN | Forward | TGT CCA TCC TCC ACC CCT CT |

| Reverse | CCA GGA ACT CCA CCA GGA AT | |

| FBN1 | Forward | GGA TAC ACA GGT GAT GGC TTC AC |

| Reverse | GTC GCA TTC ACA GCG GTA TCC T | |

| FLG | Forward | AGG CTC CTT CAG GCT ACA TTC |

| Reverse | CAG GAG AGT AGA CAT CTT TTG GCA | |

| IVL | Forward | TAA CCA CCC GCA GTG TCC AG |

| Reverse | ACA GAT GAC GGG CCA CCT A | |

| OCLN | Forward | TTT GTG GGA CAA GGA ACA CA |

| Reverse | ATG CCA TGG GAC TGT CAA CT | |

| IL-1β | Forward | AAA CAG ATG AAG TGC TCC TTC CAG G |

| Reverse | TGG AGA ACA CCA CTT GTT GCT CCA | |

| IL-6 | Forward | GCC TTC GGT CCA GTT GGC TT |

| Reverse | GCA GAA TGA GAT GAG TTG TC | |

| IL-8 | Forward | ACT GTG TGT AAA CAT GAC TTC C |

| Reverse | CAC TGG CAT CTT CAC TGA TTC T | |

| TNF-α | Forward | CTT GTT CCT CAG CCT CTT C |

| Reverse | GCT GGT TAT CTC TCA GCT C | |

| COX-2 | Forward | GAA TGG GGT GAT GAG CAG TT |

| Reverse | CAG AAG GGC AGG ATA CAG C | |

| GAPDH | Forward | ACC CAC TCC TCC ACC TTT GA |

| Reverse | CTG TTG CTG TAG CCA AAT TCG T | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bak, S.-U.; Jung, M.S.; Kim, D.J.; Jin, H.U.; Lee, S.Y.; An, C.E. Anti-Aging Efficacy of Low-Molecular-Weight Polydeoxyribonucleotide Derived from Paeonia lactiflora. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010220

Bak S-U, Jung MS, Kim DJ, Jin HU, Lee SY, An CE. Anti-Aging Efficacy of Low-Molecular-Weight Polydeoxyribonucleotide Derived from Paeonia lactiflora. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010220

Chicago/Turabian StyleBak, Sun-Uk, Min Sook Jung, Da Jung Kim, Hee Un Jin, Seung Youn Lee, and Chae Eun An. 2026. "Anti-Aging Efficacy of Low-Molecular-Weight Polydeoxyribonucleotide Derived from Paeonia lactiflora" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010220

APA StyleBak, S.-U., Jung, M. S., Kim, D. J., Jin, H. U., Lee, S. Y., & An, C. E. (2026). Anti-Aging Efficacy of Low-Molecular-Weight Polydeoxyribonucleotide Derived from Paeonia lactiflora. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010220