Flavonoids: Potential New Drug Candidates for Attenuating Vascular Remodeling in Pulmonary Hypertension

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Pulmonary Arterial Remodeling Is the Key Pathological Factor for PH

1.2. Flavonoids Compounds Have Beneficial Effects on PH

2. Pathological Mechanisms Underlying Pulmonary Arterial Remodeling

2.1. Endothelial Dysfunction and Endothelial–Mesenchymal Transition

2.2. Smooth Muscle Cell Phenotypic Transformation

2.3. Vascular Adventitia Remodeling

2.4. Other Mechanisms Underlying Pulmonary Arterial Remodeling

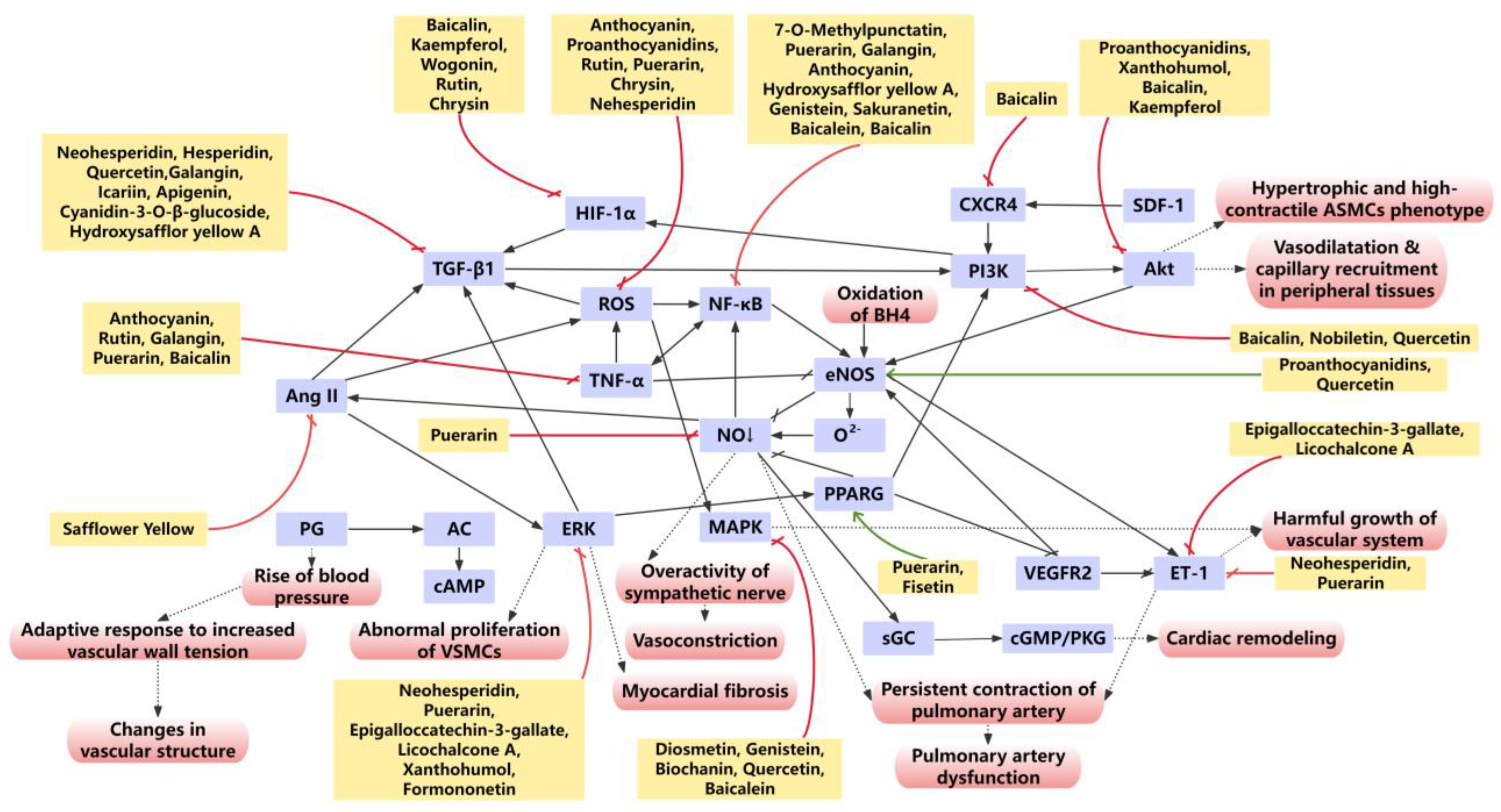

3. Flavonoids Suppress Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Pulmonary Arterial Remodeling

3.1. Flavonoids Protects Pulmonary Arteries from Oxidative Stress Injury

3.2. Flavonoids Suppress Inflammatory Responses in Pulmonary Arterial Remodeling

3.2.1. TNFα

3.2.2. TGFβ

3.2.3. IL-6

4. Flavonoids Target Specific Signaling Pathways Involved in Pulmonary Arterial Remodeling

4.1. BMPR2

4.2. PPARγ

4.3. MAPK/ERK

4.4. Nrf2

4.5. NF-κB

4.6. PI3K/Akt

5. Flavonoids Regulate the Function of PA

5.1. NO and ET-1

5.2. PGI2

5.3. MMP-2/9

5.4. Ca2+

6. Clinical Trials of Flavonoids in Cardiovascular Diseases

7. The Dilemma and Solution of Developing Flavonoids into Anti-PH Drugs

8. Discussion and Further Consideration

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Akt | protein kinase B |

| Ang II | angiotensin II |

| BCL-XL | B-cell lymphoma-extra large |

| BMP | bone morphogenetic protein |

| BMPR | bone morphogenetic protein receptor |

| CAT | catalase |

| CD31 | endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| cGMP | cyclic guanosine monophosphate |

| COPD | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| COX-2 | cyclooxygenase-2 |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| EndoMT | endothelial-mesenchymal transition |

| eNOS | endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| ET | endothelin |

| ETAR | endothelin A receptor |

| FMn | formononetin |

| GSK3β | glycogen synthase kinase 3β |

| HIF | hypoxia-inducible factor |

| HO-1 | heme oxygenase-1 |

| HPAEC | human pulmonary artery endothelial cell |

| HPH | hypoxic pulmonary hypertension |

| HPV | hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| IL-6R | interleukin-6 receptor |

| ISL | isoliquiritigenin |

| JNK | C-Jun N-terminal Kinase |

| Kv | voltage-gated potassium |

| L-NAME | N-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MCT | monocrotaline |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| MMP | matrix metalloprotein |

| mPAP | mean pulmonary arterial pressure |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-B |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| NOX4 | NADPH oxidase 4 |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 |

| PA | pulmonary artery |

| PAEC | pulmonary artery endothelial cell |

| PASMC | pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell |

| PDE5 | phosphodiesterase type 5 |

| PDGF-BB | platelet-derived growth factor-BB |

| PGI2 | prostaglandin I2 |

| PH | pulmonary hypertension |

| PI3K | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase |

| PKC | protein kinase C |

| PPAR | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| sGC | soluble guanylate cyclase |

| SOCE | store-operated calcium entry |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| STAT3 | transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TGFβ | transforming growth factor β |

| TNF-R1 | tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 |

| TNFα | tumor necrosis factor α |

| VCAM-1 | vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VSMC | vascular smooth muscle cell |

| WSPH | World Symposia on Pulmonary Hypertension |

| α-SMA | α-smooth muscle actin |

| [Ca2+]i | intracellular calcium concentration |

References

- Mocumbi, A.; Humbert, M.; Saxena, A.; Jing, Z.C.; Sliwa, K.; Thienemann, F.; Archer, S.L.; Stewart, S. Pulmonary Hypertension. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2024, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moutchia, J.; McClelland, R.L.; Al-Naamani, N.; Appleby, D.H.; Holmes, J.H.; Minhas, J.; Mazurek, J.A.; Palevsky, H.I.; Ventetuolo, C.E.; Kawut, S.M. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Treatment: An Individual Participant Data Network Meta-Analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 1937–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condon, D.F.; Nickel, N.P.; Anderson, R.; Mirza, S.; de Jesus Perez, V.A. The 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension: What’s Old Is New. F1000Research 2019, 8, F1000-Faculty. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 Esc/Ers Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3618–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auth, R.; Klinger, J.R. Emerging Pharmacotherapies for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2023, 32, 1025–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Guignabert, C.; Bonnet, S.; Dorfmüller, P.; Klinger, J.R.; Nicolls, M.R.; Olschewski, A.J.; Pullamsetti, S.S.; Schermuly, R.T.; Stenmark, K.R.; et al. Pathology and Pathobiology of Pulmonary Hypertension: State of the Art and Research Perspectives. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Zhu, S.K.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.A.; Tong, X.H.; Wan, J.Q.; Ding, J.W. New Progress in Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2022, 17, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girerd, B.; Coulet, F.; Jaïs, X.; Eyries, M.; Van Der Bruggen, C.; De Man, F.; Houweling, A.; Dorfmüller, P.; Savale, L.; Sitbon, O.; et al. Characteristics of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Affected Carriers of a Mutation Located in the Cytoplasmic Tail of Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor Type 2. Chest 2015, 147, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, A.; Tennakoon, T.; Schwarz, M.A. Emerging Epigenetic Targets and Their Molecular Impact on Vascular Remodeling in Pulmonary Hypertension. Cells 2024, 13, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.X.; Shi, J.Z.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, L.L.; Kou, J.J.; He, Y.Y.; Xie, X.M.; Zhang, S.J.; Pang, X.B. Rna M6a Methylation and Regulatory Proteins in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Hypertens. Res. 2024, 47, 1273–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.A.R.; Lawrie, A. Targeting Vascular Remodeling to Treat Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Trends Mol. Med. 2017, 23, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humbert, M.; McLaughlin, V.; Gibbs, J.S.R.; Gomberg-Maitland, M.; Hoeper, M.M.; Preston, I.R.; Souza, R.; Waxman, A.; Escribano Subias, P.; Feldman, J.; et al. Sotatercept for the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1204–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.R.; Atabay, E.K.; Liu, J.; Ding, Y.; Briscoe, S.D.; Alexander, M.J.; Andre, P.; Kumar, R.; Li, G. Sotatercept Analog Improves Cardiopulmonary Remodeling and Pulmonary Hypertension in Experimental Left Heart Failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1064290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, A.; Cheng, T.L.; Peacock, L.; Mikulec, K.; Little, D.G.; Schindeler, A. Rap-011 Augments Callus Formation in Closed Fractures in Rats. J. Orthop. Res. 2016, 34, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, N.; Wang, T.; Gan, Q.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Jin, B. Plant Flavonoids: Classification, Distribution, Biosynthesis, and Antioxidant Activity. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, C. Pharmacological Properties of Extracts and Prenylated Isoflavonoids from the Fruits of Osage Orange (Maclura Pomifera (Raf.) C.K.Schneid.). Fitoterapia 2024, 177, 106112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, J.; Parween, G.; Khator, R.; Monga, V. A Comprehensive Review of Apigenin a Dietary Flavonoid: Biological Sources, Nutraceutical Prospects, Chemistry and Pharmacological Insights and Health Benefits. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 65, 4529–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y. Clinical Study of Puerarin in Treatment of Patients with Unstable Angina. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 1998, 18, 282–284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, G. Overview and Recent Progress on the Biosynthesis and Regulation of Flavonoids in Ginkgo biloba L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Zhang, H.; Chen, D.; Chen, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Fang, L.; Du, G. Puerarin Protects Pulmonary Arteries from Hypoxic Injury through the Bmprii and Pparγ Signaling Pathways in Endothelial Cells. Pharmacol. Rep. 2019, 71, 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, H.F.; Yuan, T.Y.; Sun, S.C.; Wang, R.R.; Wang, S.B.; Fang, L.H.; Lyu, Y.; Du, G.H. Puerarin-V Prevents the Progression of Hypoxia- and Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension in Rodent Models. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2022, 43, 2325–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, L.; Ding, M.; Ding, C.; Sun, Y.; Lin, Q.; Huang, X.; et al. Puerarin Induces Mitochondria-Dependent Apoptosis in Hypoxic Human Pulmonary Arterial Smooth Muscle Cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Sheng, J.; Li, S.; Li, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; He, S.; Bai, J.; et al. Puerarin Prevents Progression of Experimental Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension Via Inhibition of Autophagy. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 141, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zou, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, W.; Chen, S. Effects of Puerarin on Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling and Protein Kinase C-Alpha in Chronic Cigarette Smoke Exposure Smoke-Exposed Rats. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Med. Sci. 2008, 28, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.J.; Cheng, D.Y.; Yang, L.; Xia, X.Q.; Guan, J. Effect of Breviscapine on Fractalkine Expression in Chronic Hypoxic Rats. Chin. Med. J. 2006, 119, 1465–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Chen, G.; He, H.; Liu, C.; Xiong, X.; Li, J.; Wang, J. Therapeutic Effects of Breviscapine in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; Liu, S.; Yuan, T.; Guo, J.; Fang, L.; Du, G. Systematic Elucidation of the Mechanism of Genistein against Pulmonary Hypertension Via Network Pharmacology Approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, Y.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Tausif, R.; Yang, Y. Genistein Rescues Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension through Estrogen Receptor and Β-Adrenoceptor Signaling. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 58, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Yu, S.; Zhang, W.; Peng, Y.; Pu, M.; Kang, T.; Zeng, J.; Yu, Y.; Li, G. Genistein Attenuates Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Rats by Activating Pi3k/Akt/Enos Signaling. Histol. Histopathol. 2017, 32, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriyama, S.; Morio, Y.; Toba, M.; Nagaoka, T.; Takahashi, F.; Iwakami, S.; Seyama, K.; Takahashi, K. Genistein Attenuates Hypoxic Pulmonary Hypertension Via Enhanced Nitric Oxide Signaling and the Erythropoietin System. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2014, 306, L996–L1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matori, H.; Umar, S.; Nadadur, R.D.; Sharma, S.; Partow-Navid, R.; Afkhami, M.; Amjedi, M.; Eghbali, M. Genistein, a Soy Phytoestrogen, Reverses Severe Pulmonary Hypertension and Prevents Right Heart Failure in Rats. Hypertension 2012, 60, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henno, P.; Maurey, C.; Danel, C.; Bonnette, P.; Souilamas, R.; Stern, M.; Delclaux, C.; Lévy, M.; Israël-Biet, D. Pulmonary Vascular Dysfunction in End-Stage Cystic Fibrosis: Role of Nf-Kappab and Endothelin-1. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 34, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, N.; Morio, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Yamamoto, A.; Suzuki, T.; Sato, K.; Muramatsu, M.; Fukuchi, Y. Genistein, a Phytoestrogen, Attenuates Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension. Respiration 2006, 73, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajabi, S.; Najafipour, H.; Jafarinejad Farsangi, S.; Joukar, S.; Beik, A.; Iranpour, M.; Kordestani, Z. Perillyle Alcohol and Quercetin Ameliorate Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Artery Hypertension in Rats through Parp1-Mediated Mir-204 Down-Regulation and Its Downstream Pathway. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; He, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, X. The Ire1α-Xbp1 Pathway Function in Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling, Is Upregulated by Quercetin, Inhibits Apoptosis and Partially Reverses the Effect of Quercetin in Pasmcs. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2019, 11, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Zhu, X.; Huang, W.; He, Y.; Pang, L.; Lan, X.; Shui, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, C.; Lei, W. Quercetin Inhibits Pulmonary Arterial Endothelial Cell Transdifferentiation Possibly by Akt and Erk1/2 Pathways. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 6147294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, W.; Wang, J.; Xin, Q.; Sun, C.; Li, K.; Qi, T.; Luan, Y. Protective Effect of Baicalin against Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Vascular Remodeling through Regulation of Tnf-A Signaling Pathway. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2021, 9, e00703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Sun, C.; Kong, F.; Wang, J.; Xin, Q.; Jiang, W.; Li, K.; Chen, O.; Luan, Y. Baicalin Attenuates Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension through Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling Pathway. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 63430–63441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.X.; Wang, X.D.; Wang, H.X.; Liu, T. Baicalin Attenuates Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling by Inhibiting Calpain-1 Mediated Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Heliyon 2023, 9, e23076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiwara, T.; Takeda, N.; Hara, H.; Ishii, S.; Numata, G.; Tokiwa, H.; Katoh, M.; Maemura, S.; Suzuki, T.; Takiguchi, H.; et al. Pgc-1α-Mediated Angiogenesis Prevents Pulmonary Hypertension in Mice. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e162632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Wang, J.; Yi, T.; Cheng, J.; Guo, H.; He, Y.; Shui, X.; Wu, Z.; Huang, S.; Lei, W. Baicalin Prevents Pulmonary Arterial Remodeling in Vivo Via the Akt/Erk/Nf-Κb Signaling Pathways. Pulm. Circ. 2019, 9, 1–10, Correction in Pulm. Circ. 2022, 12, e12122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Wu, P.; Huang, F.; Xu, M.; Chen, M.; Huang, K.; Li, G.P.; Xu, M.; Yao, D.; Wang, L. Baicalin Attenuates Chronic Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension Via Adenosine a(2a) Receptor-Induced Sdf-1/Cxcr4/Pi3k/Akt Signaling. J. Biomed. Sci. 2017, 24, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Yuan, T.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, D.; Liu, C.; Guo, J.; Chen, Y. Mechanistic and therapeutic perspectives of baicalin and baicalein on pulmonary hypertension: A comprehensive review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 151, 113191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, W.L.; Lin, Y.C.; Jeng, J.R.; Chang, H.Y.; Chou, T.C. Baicalein Ameliorates Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Caused by Monocrotaline through Downregulation of Et-1 and Et(a)R in Pneumonectomized Rats. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2018, 46, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Wei, Z.; Zhu, D.; Fu, N.; Wang, C.; Yin, S.; Liang, Y.; Xing, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. Baicalein Attenuates Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension by Inhibiting Vascular Remodeling in Rats. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 48, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preston, I.R.; Hill, N.S.; Warburton, R.R.; Fanburg, B.L. Role of 12-Lipoxygenase in Hypoxia-Induced Rat Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2006, 290, L367–L374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Cai, C.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Ye, S.; Zhao, H.; Zeng, C. Icariin Attenuates Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Via the Inhibition of Tgf-Β1/Smads Pathway in Rats. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 9238428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.S.; Luo, Y.M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, X.X.; Yang, D.L. Icariin Inhibits Pulmonary Hypertension Induced by Monocrotaline through Enhancement of NO/cGMP Signaling Pathway in Rats. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2016, 2016, 7915415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.Y.; Lei, C.J.; Kong, S.; Li, H.F.; Pan, S.Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Zhao, F.R.; Zhu, T.T. Hydroxy-Safflower Yellow a Mitigates Vascular Remodeling in Rat Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2024, 18, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, X.; Long, Y. Hydroxysafflor Yellow a Improves Established Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Rats. J. Int. Med. Res. 2016, 44, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Dong, P.; Hou, C.; Cao, F.; Sun, S.; He, F.; Song, Y.; Li, S.; Bai, Y.; Zhu, D. Hydroxysafflor Yellow a (Hsya) Attenuates Hypoxic Pulmonary Arterial Remodelling and Reverses Right Ventricular Hypertrophy in Rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 186, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Lu, P.; Han, C.; Yu, C.; Chen, M.; He, F.; Yi, D.; Wu, L. Hydroxysafflor Yellow a (Hsya) from Flowers of Carthamus tinctorius L. And Its Vasodilatation Effects on Pulmonary Artery. Molecules 2012, 17, 14918–14927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, H.; Yi, J.; Zhao, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, X.; Fu, J.; Li, Q. Characterization of Pkcα-Rutin Interactions and Their Application as a Treatment Strategy for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension by Inhibiting Ferroptosis. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 779–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Mao, M.; Lv, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Li, X.; Zheng, X. Antioxidant Mechanism of Rutin on Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Cell Proliferation. Molecules 2014, 19, 19036–19049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Kim, J.D.; Naito, A.; Yanagisawa, A.; Jujo-Sanada, T.; Kasuya, Y.; Nakagawa, Y.; Sakao, S.; Tatsumi, K.; Suzuki, T. Multi-Omics Analysis of Right Ventricles in Rat Models of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Consideration of Mitochondrial Biogenesis by Chrysin. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2022, 49, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, L.; Peng, Y.; Guo, Z. Chrysin Alleviates Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension in Rats through Regulation of Intracellular Calcium Homeostasis in Pulmonary Arterial Smooth Muscle Cells. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2020, 75, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.W.; Wang, X.M.; Li, S.; Yang, J.R. Effects of Chrysin (5,7-Dihydroxyflavone) on Vascular Remodeling in Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension in Rats. Chin. Med. 2015, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, S.; Lan, T.; Yang, J.; Li, L. Chrysin Alleviates Chronic Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension by Reducing Intracellular Calcium Concentration in Pulmonary Arterial Smooth Muscle Cells. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2019, 74, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.T.; Zhang, W.F.; Luo, P.; He, F.; Ge, X.Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, C.P. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Ameliorates Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling by Promoting Mitofusin-2-Mediated Mitochondrial Fusion. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 809, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shu, Z.; Yu, M.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, X.; Wu, L.; Tan, X. Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate Inhibits Proliferation of Human Aortic Smooth Muscle Cells Via up-Regulating Expression of Mitofusin 2. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 93, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, A.; Sarkar, J.; Chakraborti, T.; Chakraborti, S. Role of Spm-Cer-S1p Signalling Pathway in Mmp-2 Mediated U46619-Induced Proliferation of Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cells: Protective Role of Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2015, 33, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Pan, J.; Han, J.; Wang, Y.; Lei, H.; Ding, Y.; Yuan, Y. Grape Seed Procyanidin Extract Attenuates Hypoxic Pulmonary Hypertension by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and Pulmonary Arterial Smooth Muscle Cells Proliferation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 36, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hu, S.; Zhu, B.; Shao, S.; Yuan, L. Grape Seed Procyanidin Suppresses Inflammation in Cigarette Smoke-Exposed Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Rats by the Ppar-Γ/Cox-2 Pathway. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Yan, J.; Meng, H.; Zhan, H.; Chen, L.; Yuan, L. Grape Seed Proanthocyanidin Inhibits Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Via Attenuating Inflammation: In Vivo and in Vitro Studies. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 67, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Wang, H.; Yan, J.; Lai, J.; Cai, S.; Yuan, L.; Zheng, S. Grape Seed Proanthocyanidin Reverses Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling in Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension by Down-Regulating Hsp70. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 101, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Duan, Q.; Ren, J.; Yi, J.; Yu, H.; Che, H.; Yang, C.; Wang, X.; Li, Q. Targeted Metabolomics Combined with Network Pharmacology to Reveal the Protective Role of Luteolin in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 10695–10709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Su, S.; Xin, M.; Zhang, Z.; Nan, X.; Li, Z.; Lu, D. Luteolin Ameliorates Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension Via Regulating Hif-2α-Arg-No Axis and Pi3k-Akt-Enos-No Signaling Pathway. Phytomedicine 2022, 104, 154329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.; Liu, N.; Zeng, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Wu, K.; Yang, F.; Li, B.; Song, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, Q. Luteolin Ameliorates Experimental Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Via Suppressing Hippo-Yap/Pi3k/Akt Signaling Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 663551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Su, S.; Nan, X.; Xie, X.; Li, Z.; Lu, D. Kaempferol Ameliorates Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling in Chronic Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension Rats Via Regulating Akt-Gsk3β-Cyclin Axis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2023, 466, 116478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Wang, X.; Song, K.; Ren, J.; Che, H.; Yu, H.; Li, Q. Integrated Metabolomics and Mechanism to Reveal the Protective Effect of Kaempferol on Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 212, 114662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahobiya, A.; Singh, T.U.; Rungsung, S.; Kumar, T.; Chandrasekaran, G.; Parida, S.; Kumar, D. Kaempferol-Induces Vasorelaxation Via Endothelium-Independent Pathways in Rat Isolated Pulmonary Artery. Pharmacol. Rep. 2018, 70, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Cai, C.; Yang, L.; Xiang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zeng, C. Inhibitory Effects of Formononetin on the Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Rats. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 21, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, C.; Xiang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, N.; Zhao, H.; Xu, J.; Lin, W.; Zeng, C. Formononetin Attenuates Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Via Inhibiting Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling in Rats. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 20, 4984–4992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Jiang, Y.; Du, F.; Guo, L.; Wang, G.; Kim, S.C.; Lee, C.W.; Shen, L.; Zhao, R. Isoliquiritigenin Attenuates Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension Via Inhibition of the Inflammatory Response and Pasmcs Proliferation. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2019, 2019, 4568198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Fang, X.; Shi, J.; Li, X.; Xie, M.; Liu, X. Apigenin Attenuates Pulmonary Hypertension by Inducing Mitochondria-Dependent Apoptosis of Pasmcs Via Inhibiting the Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1α-Kv1.5 Channel Pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 317, 108942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Tianxin, Y.; Zhangchi, L.; Cui, Z.; Weiguo, W.; Bo, Y. Pinocembrin Attenuates Susceptibility to Atrial Fibrillation in Rats with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 960, 176169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, L.A.; Rizk, S.M.; El-Maraghy, S.A. Pinocembrin Ex Vivo Preconditioning Improves the Therapeutic Efficacy of Endothelial Progenitor Cells in Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension in Rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 138, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Wang, J.L.; Jing, Z.C.; Ma, P.; Xu, Q.B.; Na, J.R.; Tian, J.; Ma, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, R. Protective Effects of Isorhamnetin on Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: In Vivo and in Vitro Studies. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 2730–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, D.; Liu, L.; Bourouis, S.; Algarni, A.D.; Zhong, C.; Wu, P. An Optimized Machine Learning Method for Predicting Wogonin Therapy for the Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension. Comput. Biol. Med. 2023, 164, 107293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, L.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, X.; Yuan, T.; Wang, C.; Liu, D.; Guo, J.; Chen, Y. Deciphering the Mechanism of Wogonin, a Natural Flavonoid, on the Proliferation of Pulmonary Arterial Smooth Muscle Cells by Integrating Network Pharmacology and in Vitro Validation. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Deng, W.; Cheng, Z.; Guo, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; He, Y.; Tang, Q. Effects of Hesperetin on Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-Bb-Induced Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, L.A.; Obaid, A.A.; Zaki, H.F.; Agha, A.M. Naringenin Adds to the Protective Effect of L-Arginine in Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension in Rats: Favorable Modulation of Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Nitric Oxide. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 62, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordenave, J.; Thuillet, R.; Tu, L.; Phan, C.; Cumont, A.; Marsol, C.; Huertas, A.; Savale, L.; Hibert, M.; Galzi, J.L.; et al. Neutralization of Cxcl12 Attenuates Established Pulmonary Hypertension in Rats. Cardiovasc. Res. 2020, 116, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhu, X.; Zeng, Z.; Wu, X.; Xu, Y.; Xie, J.; Yu, J. Dihydromyricetin Prevents Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 96, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Fan, C.; Yu, Y.; Li, J.; Mei, F.; Zhang, S.; Xi, R.; Zhang, X. Nobiletin Attenuates Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension through Pi3k/Akt/Stat3 Pathway. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2023, 75, 1100–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, S.A.; Venkatasubramanian, R.; Darrah, M.A.; Ludwig, K.R.; VanDongen, N.S.; Greenberg, N.T.; Longtine, A.G.; Hutton, D.A.; Brunt, V.E.; Campisi, J.; et al. Intermittent Supplementation with Fisetin Improves Arterial Function in Old Mice by Decreasing Cellular Senescence. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, F.; Pei, H.; Su, C.; Du, L.; Wang, J.; Xie, F.; Yin, Q.; Gao, Z. Fisetin Alleviates Neointimal Hyperplasia Via Pparγ/Pon2 Antioxidative Pathway in Shr Rat Artery Injury Model. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021, 2021, 6625517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.G.; Sung, J.Y.; Kang, Y.J.; Choi, H.C. Pparγ Activation by Fisetin Mitigates Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Senescence Via the Mtorc2-Foxo3a-Autophagy Signaling Pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 218, 115892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Hui, Y.; Liu, F.; Yang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Chang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Ding, Y. Neohesperidin Protects Angiotensin Ii-Induced Hypertension and Vascular Remodeling. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 890202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Javed, A.; Khan, T.; Althobaiti, Y.S.; Ullah, A.; Almutairi, F.M.; Shah, A.J. Investigation into the Antihypertensive Effects of Diosmetin and Its Underlying Vascular Mechanisms Using Rat Model. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meephat, S.; Prasatthong, P.; Potue, P.; Bunbupha, S.; Pakdeechote, P.; Maneesai, P. Diosmetin Ameliorates Vascular Dysfunction and Remodeling by Modulation of Nrf2/Ho-1 and P-Jnk/P-Nf-Κb Expression in Hypertensive Rats. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaihongsa, N.; Maneesai, P.; Sangartit, W.; Potue, P.; Bunbupha, S.; Pakdeechote, P. Galangin Alleviates Vascular Dysfunction and Remodelling through Modulation of the Tnf-R1, P-Nf-Κb and Vcam-1 Pathways in Hypertensive Rats. Life Sci. 2021, 285, 119965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardoun, M.; Iratni, R.; Dehaini, H.; Eid, A.; Ghaddar, T.; El-Elimat, T.; Alali, F.; Badran, A.; Eid, A.H.; Baydoun, E. 7-O-Methylpunctatin, a Novel Homoisoflavonoid, Inhibits Phenotypic Switch of Human Arteriolar Smooth Muscle Cells. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Lim, H.J.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, S.; Kwak, H.J.; Cha, J.H.; Park, H.Y. Anti-Proliferative Effect of Licochalcone a on Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 1996–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, S.R.; Stickland, M.K. The Pulmonary Vasculature. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 44, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolluru, G.K.; Glawe, J.D.; Pardue, S.; Kasabali, A.; Alam, S.; Rajendran, S.; Cannon, A.L.; Abdullah, C.S.; Traylor, J.G.; Shackelford, R.E.; et al. Methamphetamine Causes Cardiovascular Dysfunction Via Cystathionine Gamma Lyase and Hydrogen Sulfide Depletion. Redox Biol. 2022, 57, 102480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimbrone, M.A., Jr.; Topper, J.N.; Nagel, T.; Anderson, K.R.; Garcia-Cardeña, G. Endothelial Dysfunction, Hemodynamic Forces, and Atherogenesis. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 2000, 902, 230–239; discussion 239–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubanyi, G.M.; Romero, J.C.; Vanhoutte, P.M. Flow-Induced Release of Endothelium-Derived Relaxing Factor. Am. J. Physiol. 1986, 250, H1145–H1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchan, M.J.; Frangos, J.A. Role of Calcium and Calmodulin in Flow-Induced Nitric Oxide Production in Endothelial Cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1994, 266, C628–C636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benza, R.L.; Grünig, E.; Sandner, P.; Stasch, J.P.; Simonneau, G. The Nitric Oxide-Soluble Guanylate Cyclase-Cgmp Pathway in Pulmonary Hypertension: From Pde5 to Soluble Guanylate Cyclase. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2024, 33, 230183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Murase, M. Outcomes of High-Dose Inhaled Nitric Oxide and Oxygen Administration for Severe Pulmonary Hypertension with Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Cureus 2024, 16, e58855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Yuan, T.; Wang, R.; Gong, D.; Wang, S.; Du, G.; Fang, L. Insights into Endothelin Receptors in Pulmonary Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitopoulou, I.; Orfanos, S.E.; Kotanidou, A.; Maltabe, V.; Manitsopoulos, N.; Karras, P.; Kouklis, P.; Armaganidis, A.; Maniatis, N.A. Vascular Endothelial-Cadherin Downregulation as a Feature of Endothelial Transdifferentiation in Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2016, 311, L352–L363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gairhe, S.; Awad, K.S.; Dougherty, E.J.; Ferreyra, G.A.; Wang, S.; Yu, Z.X.; Takeda, K.; Demirkale, C.Y.; Torabi-Parizi, P.; Austin, E.D.; et al. Type I Interferon Activation and Endothelial Dysfunction in Caveolin-1 Insufficiency-Associated Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2010206118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feron, O.; Dessy, C.; Moniotte, S.; Desager, J.P.; Balligand, J.L. Hypercholesterolemia Decreases Nitric Oxide Production by Promoting the Interaction of Caveolin and Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 103, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marudamuthu, A.S.; Bhandary, Y.P.; Fan, L.; Radhakrishnan, V.; MacKenzie, B.; Maier, E.; Shetty, S.K.; Nagaraja, M.R.; Gopu, V.; Tiwari, N.; et al. Caveolin-1-Derived Peptide Limits Development of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaat2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Tong, X. Advances in Molecular Mechanism of Vascular Remodeling in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2019, 48, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranchoux, B.; Antigny, F.; Rucker-Martin, C.; Hautefort, A.; Péchoux, C.; Bogaard, H.J.; Dorfmüller, P.; Remy, S.; Lecerf, F.; Planté, S.; et al. Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Pulmonary Hypertension. Circulation 2015, 131, 1006–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klouda, T.; Kim, Y.; Baek, S.H.; Bhaumik, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.C.; Raby, B.A.; Perez, V.J.; Yuan, K. Specialized Pericyte Subtypes in the Pulmonary Capillaries. EMBO J. 2025, 44, 1074–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Régent, A.; Ly, K.H.; Lofek, S.; Clary, G.; Tamby, M.; Tamas, N.; Federici, C.; Broussard, C.; Chafey, P.; Liaudet-Coopman, E.; et al. Proteomic Analysis of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells in Physiological Condition and in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Toward Contractile Versus Synthetic Phenotypes. Proteomics 2016, 16, 2637–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badran, A.; Nasser, S.A.; Mesmar, J.; El-Yazbi, A.F.; Bitto, A.; Fardoun, M.M.; Baydoun, E.; Eid, A.H. Reactive Oxygen Species: Modulators of Phenotypic Switch of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.; Chen, M.; Huang, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Tgf-Β1/Fgf-2 Signaling Mediates the 15-Hete-Induced Differentiation of Adventitial Fibroblasts into Myofibroblasts. Lipids Health Dis. 2016, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimaki, E.; Muola, P.; Parkkila, S.; Kholová, I.; Haapasalo, H.; Pastorekova, S.; Pastorek, J.; Paavonen, T.; Mennander, A. Carbonic Anhydrase Ix Deposits Are Associated with Increased Ascending Aortic Dilatation. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2016, 50, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group of Pulmonary Embolism and Pulmonary Vascular Disease; Respiratory Disease Branch of Chinese Medical As-sociation; Working Committee of Pulmonary Embolism and Pulmonary Vascular Disease, Respiratory Physician Branch of Chinese Medical Association; National Collaborative Group on Prevention and Treatment of Pulmonary Embolism and Pulmonary Vascular Disease; National Expert Panel for the Standardized System Construction Project for Pulmonary Hypertension. Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension in China, 2021 Edition. Chin. Med. J. 2021, 101, 11–51.

- Pokharel, M.D.; Marciano, D.P.; Fu, P.; Franco, M.C.; Unwalla, H.; Tieu, K.; Fineman, J.R.; Wang, T.; Black, S.M. Metabolic Reprogramming, Oxidative Stress, and Pulmonary Hypertension. Redox Biol. 2023, 64, 102797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, M.; Lakshminrusimha, S.; Vento, M. Pulmonary Hypertension and Oxidative Stress: Where Is the Link? Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022, 27, 101347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, C.; Yang, D.; Jin, M.; Bai, C.; Song, Y. Urban Particulate Matter Triggers Lung Inflammation Via the Ros-Mapk-Nf-Κb Signaling Pathway. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 4398–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demarco, V.G.; Whaley-Connell, A.T.; Sowers, J.R.; Habibi, J.; Dellsperger, K.C. Contribution of Oxidative Stress to Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. World J. Cardiol. 2010, 2, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Leng, W.; Zhang, J. Protective Effect of Puerarin against Oxidative Stress Injury of Neural Cells and Related Mechanisms. Med. Sci. Monit. 2016, 22, 1244–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. In Vitro and in Vivo Antitumour Activities of Puerarin 6″-O-Xyloside on Human Lung Carcinoma A549 Cell Line Via the Induction of the Mitochondria-Mediated Apoptosis Pathway. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 1793–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Yu, L.; Chen, J. The Puerarin Improves Renal Function in Stz-Induced Diabetic Rats by Attenuating Enos Expression. Ren. Fail. 2015, 37, 699–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yao, M.; Qi, J.; Song, R.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Chang, D.; Huang, Q.; Li, L.; et al. Puerarin Inhibited Oxidative Stress and Alleviated Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury through Pi3k/Akt/Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1134380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, P.T.; Huang, S.E.; Hsu, J.H.; Kuo, C.H.; Chao, Y.Y.; Wang, L.S.; Yeh, J.L. Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidative Effects of Puerarin in Postmenopausal Cardioprotection: Roles of Akt and Heme Oxygenase-1. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2023, 51, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinh, P.T.N.; Truc, N.C.; Danh, T.T.; Trang, N.T.T.; Le Hang, D.T.; Vi, L.N.T.; Hung, Q.T.; Dung, L.T. A Study on the Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitory Activity of the Artemisia vulgaris L. Extract and Its Fractions. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 334, 118519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauf, A.; Imran, M.; Abu-Izneid, T.; Iahtisham Ul, H.; Patel, S.; Pan, X.; Naz, S.; Sanches Silva, A.; Saeed, F.; Rasul Suleria, H.A. Proanthocyanidins: A Comprehensive Review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 116, 108999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.A.; Ferraz, E.R.; Souza, A.O.; Lourenço, R.A.; Oliveira, D.P.; Dorta, D.J. Evaluation of the Mutagenic Activity of Chrysin, a Flavonoid Inhibitor of the Aromatization Process. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2012, 75, 1000–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ding, W.; Yang, X.; Lu, T.; Liu, Y. Isoliquiritigenin, a Potential Therapeutic Agent for Treatment of Inflammation-Associated Diseases. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 318, 117059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Ma, K.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q.; Xu, H. Isoliquiritigenin as a Modulator of the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway: Potential Therapeutic Implications. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1395735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmsen, P.K.; Spada, D.S.; Salvador, M. Antioxidant Activity of the Flavonoid Hesperidin in Chemical and Biological Systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4757–4761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraj, P.; Pugalendi, K.V. Hesperidin, a Flavanone Glycoside, on Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidant Status in Experimental Myocardial Ischemic Rats. Redox Rep. 2010, 15, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Liao, J.H. Potential Role of Hesperidin in Improving Experimental Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Rats Via Modulation of the Nf-Κb Pathway. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2025, 105, e70068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdem, I.; Aktas, S.; Ogut, S. Neohesperidin Dihydrochalcone Ameliorates Experimental Colitis Via Anti-Inflammatory, Antioxidative, and Antiapoptosis Effects. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 15715–15724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Autieri, M.V.; Carbone, C.M. Overexpression of Allograft Inflammatory Factor-1 Promotes Proliferation of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells by Cell Cycle Deregulation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2001, 21, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correale, M.; Tricarico, L.; Bevere, E.M.L.; Chirivì, F.; Croella, F.; Severino, P.; Mercurio, V.; Magrì, D.; Dini, F.; Licordari, R.; et al. Circulating Biomarkers in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: An Update. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucly, A.; Tu, L.; Guignabert, C.; Rhodes, C.; De Groote, P.; Prévot, G.; Bergot, E.; Bourdin, A.; Beurnier, A.; Roche, A.; et al. Cytokines as Prognostic Biomarkers in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2201232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobal, R.; Potjewijd, J.; de Vries, F.; van Doorn, D.P.C.; Jaminon, A.; Bittner, R.; Akbulut, C.; van Empel, V.; Heeringa, P.; Damoiseaux, J.; et al. Dephosphorylated Uncarboxylated Matrix-Gla-Protein as Candidate Biomarker for Immune-Mediated Vascular Remodeling and Prognosis in Pulmonary Hypertension. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Li, P.; Liu, S.; Sun, Y.; Chen, C.; Long, J.; Lin, Y.; Liang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; et al. Dihydromyricetin Treats Pulmonary Hypertension by Modulating Cklf1/Ccr5 Axis-Induced Pulmonary Vascular Cell Pyroptosis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 180, 117614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Q.; Wang, H.M.; Yang, C.G.; Zhang, X.H.; Han, D.D.; Wang, H.L. Fluoxetine Inhibited Extracellular Matrix of Pulmonary Artery and Inflammation of Lungs in Monocrotaline-Treated Rats. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2011, 32, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, S.; Qian, J.; Wu, G.; Qian, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, T.; Wang, J.; Huang, W.; Liang, G. Schizandrin B Attenuates Angiotensin Ii Induced Endothelial to Mesenchymal Transition in Vascular Endothelium by Suppressing Nf-Κb Activation. Phytomedicine 2019, 62, 152955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savale, L.; Tu, L.; Normand, C.; Boucly, A.; Sitbon, O.; Montani, D.; Olsson, K.M.; Park, D.H.; Fuge, J.; Kamp, J.C.; et al. Effect of Sotatercept on Circulating Proteomics in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 64, 2401483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunbupha, S.; Prachaney, P.; Kukongviriyapan, U.; Kukongviriyapan, V.; Welbat, J.U.; Pakdeechote, P. Asiatic Acid Alleviates Cardiovascular Remodelling in Rats with L-Name-Induced Hypertension. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2015, 42, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndisang, J.F.; Chibbar, R.; Lane, N. Heme Oxygenase Suppresses Markers of Heart Failure and Ameliorates Cardiomyopathy in L-Name-Induced Hypertension. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 734, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosswhite, P.; Sun, Z. Tnfα Induces DNA and Histone Hypomethylation and Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation Partly Via Excessive Superoxide Formation. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, X.; Xie, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zeng, L.; Zhuang, J.; Kuang, J.; Lin, Y.; Hu, B.; et al. N6-Methyladenosine Modification of Klf2 May Contribute to Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Pulmonary Hypertension. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2024, 29, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelko, I.N.; Zhu, J.; Ritzenthaler, J.D.; Roman, J. Pulmonary Hypertension and Vascular Remodeling in Mice Exposed to Crystalline Silica. Respir. Res. 2016, 17, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, Y.; Chao, S.; Ju, Z.Y.; Wang, J.; Xue, X.; Qi, T.G.; Cheng, G.H.; Kong, F. Therapeutic Effects of Baicalin on Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension by Inhibiting Inflammatory Response. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 26, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, C.; Li, B.; Lin, C.; Xing, X.; Huang, F.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Azevedo, H.S.; He, W. Targeted Delivery of Baicalein-P53 Complex to Smooth Muscle Cells Reverses Pulmonary Hypertension. J. Control. Release 2022, 341, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Lee, J.H.; Yim, N.H.; Han, J.H.; Ma, J.Y. Application of Galangin, an Active Component of Alpinia Officinarum Hance (Zingiberaceae), for Use in Drug-Eluting Stents. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, T.; Read, M.A.; Neish, A.S.; Whitley, M.Z.; Thanos, D.; Maniatis, T. Transcriptional Regulation of Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecules: Nf-Kappa B and Cytokine-Inducible Enhancers. FASEB J. 1995, 9, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiss, D.J.; Sattar, N. Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1: A Viable Therapeutic Target for Atherosclerosis? Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007, 61, 697–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Chen, L.; Liang, W.; Hu, T.; Sun, N.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, X. Blood Pressure and the Risk of Diabetes: A Longitudinal Observational Study Based on Chinese Individuals. J. Diabetes Investig. 2025, 16, 1081–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, H.C.; Pearlman, R.L.; Afaq, F. Fisetin and Its Role in Chronic Diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 928, 213–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, H.; Choo, S.; Kim, J.; Baek, M.C.; Bae, J.S. Fisetin Suppresses Pulmonary Inflammatory Responses through Heme Oxygenase-1 Mediated Downregulation of Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase. J. Med. Food 2020, 23, 1163–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Massagué, J. Mechanisms of Tgf-Beta Signaling from Cell Membrane to the Nucleus. Cell 2003, 113, 685–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Kanehisa, M. Kegg Tools for Classification and Analysis of Viral Proteins. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massagué, J. How Cells Read Tgf-Beta Signals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 1, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derynck, R.; Zhang, Y.E. Smad-Dependent and Smad-Independent Pathways in Tgf-Beta Family Signalling. Nature 2003, 425, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel-Carrasco, J.L.; Mate, A.; Monserrat, M.T.; Arias, J.L.; Aramburu, O.; Vázquez, C.M. The role of inflammatory markers in the cardioprotective effect of L-carnitine in L-NAME-induced hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 2008, 21, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyby, M.D.; Abedi, K.; Smutko, V.; Eslami, P.; Tuck, M.L. Vascular Angiotensin Type 1 Receptor Expression Is Associated with Vascular Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Fructose-Fed Rats. Hypertens. Res. 2007, 30, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, L.; Graham, C.F.; Gordon, S. Macrophages in Haemopoietic and Other Tissues of the Developing Mouse Detected by the Monoclonal Antibody F4/80. Development 1991, 112, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, J.Y.; Jalil, A.; Klaine, M.; Jung, S.; Cumano, A.; Godin, I. Three Pathways to Mature Macrophages in the Early Mouse Yolk Sac. Blood 2005, 106, 3004–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossadegh-Keller, N.; Gentek, R.; Gimenez, G.; Bigot, S.; Mailfert, S.; Sieweke, M.H. Developmental Origin and Maintenance of Distinct Testicular Macrophage Populations. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 2829–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottmann, R.M.; Kulkarni, A.A.; Smolnycki, K.A.; Lyda, E.; Dahanayake, T.; Salibi, R.; Honnons, S.; Jones, C.; Isern, N.G.; Hu, J.Z.; et al. Lactic Acid Is Elevated in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Induces Myofibroblast Differentiation Via Ph-Dependent Activation of Transforming Growth Factor-Β. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Jiang, X.M.; Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Xie, D.J.; Hu, Z.Y. Pulmonary Artery Denervation Improves Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Induced Right Ventricular Dysfunction by Modulating the Local Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2016, 16, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Hafez, A.; Shu, R.; Uhal, B.D. Jund and Hif-1alpha Mediate Transcriptional Activation of Angiotensinogen by Tgf-Beta1 in Human Lung Fibroblasts. FASEB J. 2009, 23, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Chen, P.; Shui, X.; He, Y.; Wang, H.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Xue, Y.; Chen, C.; et al. Baicalin Attenuates Transforming Growth Factor-Β1-Induced Human Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation and Phenotypic Switch by Inhibiting Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α and Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Expression. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2014, 66, 1469–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Lv, C.; Yu, H.; Xu, M.; Zhang, M.; Fu, Y.; Meng, H.; Zhou, J. Tgf-Β1 Inhibits the Apoptosis of Pulmonary Arterial Smooth Muscle Cells and Contributes to Pulmonary Vascular Medial Thickening Via the Pi3k/Akt Pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 13, 2751–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; Zheng, B.; Chen, T.; Chang, X.; Yin, B.; Huang, Z.; Shuai, P.; Han, L. Semen Brassicae Ameliorates Hepatic Fibrosis by Regulating Transforming Growth Factor-Β1/Smad, Nuclear Factor-Κb, and Akt Signaling Pathways in Rats. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2018, 12, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, T.; Jenkins, R.H.; Fraser, D.J. Micrornas, Transforming Growth Factor Beta-1, and Tissue Fibrosis. J. Pathol. 2013, 229, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Liu, C.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, L. Tgf-Β/Smad Pathway and Its Regulation in Hepatic Fibrosis. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2016, 64, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Hu, D.; Niu, L.; Qu, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, S. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Attenuate Vascular Remodeling in Monocrotaline-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension Rats. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Med. Sci. 2012, 32, 810–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Shao, R.; Zhang, X.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Fa, X. Up-Regulation of Caveolin-1 by Dj-1 Attenuates Rat Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension by Inhibiting Tgfβ/Smad Signaling Pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 361, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Gupta, S. Apigenin-Induced Cell Cycle Arrest Is Mediated by Modulation of Mapk, Pi3k-Akt, and Loss of Cyclin D1 Associated Retinoblastoma Dephosphorylation in Human Prostate Cancer Cells. Cell Cycle 2007, 6, 1102–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czyz, J.; Madeja, Z.; Irmer, U.; Korohoda, W.; Hülser, D.F. Flavonoid Apigenin Inhibits Motility and Invasiveness of Carcinoma Cells in Vitro. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 114, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, W. Apigenin Protects against Bleomycin-Induced Lung Fibrosis in Rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 2016, 11, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D.W.; Segall, H.J.; Pan, L.C.; Dunston, S.K. Progressive Inflammatory and Structural Changes in the Pulmonary Vasculature of Monocrotaline-Treated Rats. Microvasc. Res. 1989, 38, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golembeski, S.M.; West, J.; Tada, Y.; Fagan, K.A. Interleukin-6 Causes Mild Pulmonary Hypertension and Augments Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension in Mice. Chest 2005, 128, 572s–573s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.J.; Kang, H.K.; Nguyen, T.T.; Kim, G.E.; Kim, Y.M.; Park, J.S.; Kim, D.; Cha, J.; Moon, Y.H.; Nam, S.H.; et al. Synthesis and Characterization of Ampelopsin Glucosides Using Dextransucrase from Leuconostoc Mesenteroides B-1299cb4: Glucosylation Enhancing Physicochemical Properties. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2012, 51, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Tong, Q.; Wang, W.; Xiong, W.; Shi, C.; Fang, J. Dihydromyricetin Protects Endothelial Cells from Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Oxidative Stress Damage by Regulating Mitochondrial Pathways. Life Sci. 2015, 130, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.N.; Green, J.; Wang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Qiao, M.; Peabody, M.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, J.; Yan, Z.; Denduluri, S.; et al. Bone Morphogenetic Protein (Bmp) Signaling in Development and Human Diseases. Genes Dis. 2014, 1, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.M.T.; Giannoulatou, E.; Celermajer, D.S.; Humbert, M. Epidemiology and Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, C.; Stewart, S.; Upton, P.D.; Machado, R.; Thomson, J.R.; Trembath, R.C.; Morrell, N.W. Primary Pulmonary Hypertension Is Associated with Reduced Pulmonary Vascular Expression of Type Ii Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor. Circulation 2002, 105, 1672–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, K.B.; Machado, R.D.; Pauciulo, M.W.; Thomson, J.R.; Phillips, J.A., 3rd; Loyd, J.E.; Nichols, W.C.; Trembath, R.C. Heterozygous Germline Mutations in Bmpr2, Encoding a Tgf-Beta Receptor, Cause Familial Primary Pulmonary Hypertension. Nat. Genet. 2000, 26, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansmann, G.; Calvier, L.; Risbano, M.G.; Chan, S.Y. Activation of the Metabolic Master Regulator Pparγ: A Potential Pioneering Therapy for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 62, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T.; Higashijima, Y.; Kanki, Y.; Nakaki, R.; Kawamura, T.; Urade, Y.; Wada, Y. Perk Inhibition Attenuates Vascular Remodeling in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Caused by Bmpr2 Mutation. Sci. Signal 2021, 14, eabb3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frump, A.; Prewitt, A.; de Caestecker, M.P. Bmpr2 Mutations and Endothelial Dysfunction in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (2017 Grover Conference Series). Pulm. Circ. 2018, 8, 2045894018765840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tielemans, B.; Delcroix, M.; Belge, C.; Quarck, R. Tgfβ and Bmprii Signalling Pathways in the Pathogenesis of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Drug Discov. Today 2019, 24, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, S.; Zarga, M.A.; Afifi, F.; al-Khalil, S.; Mahasneh, A.; Sabri, S. Effects of 3,3′-Di-O-Methylquercetin on Guinea-Pig Isolated Smooth Muscle. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1989, 41, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Kan, J.; Zhang, J.; Ye, P.; Wang, D.; Jiang, X.; Li, M.; Zhu, L.; Gu, Y. Bioactive Compounds from Coptidis Rhizoma Alleviate Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension by Inhibiting Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cells’ Proliferation and Migration. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2021, 78, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goncharov, D.A.; Kudryashova, T.V.; Ziai, H.; Ihida-Stansbury, K.; DeLisser, H.; Krymskaya, V.P.; Tuder, R.M.; Kawut, S.M.; Goncharova, E.A. Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 2 (Mtorc2) Coordinates Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cell Metabolism, Proliferation, and Survival in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Circulation 2014, 129, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncharova, E.A. Mtor and Vascular Remodeling in Lung Diseases: Current Challenges and Therapeutic Prospects. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 1796–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssaini, A.; Abid, S.; Mouraret, N.; Wan, F.; Rideau, D.; Saker, M.; Marcos, E.; Tissot, C.M.; Dubois-Randé, J.L.; Amsellem, V.; et al. Rapamycin Reverses Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation in Pulmonary Hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 48, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.H.; Pacold, M.E.; Perisic, O.; Stephens, L.; Hawkins, P.T.; Wymann, M.P.; Williams, R.L. Structural Determinants of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Inhibition by Wortmannin, Ly294002, Quercetin, Myricetin, and Staurosporine. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Cano, D.; Menendez, C.; Moreno, E.; Moral-Sanz, J.; Barreira, B.; Galindo, P.; Pandolfi, R.; Jimenez, R.; Moreno, L.; Cogolludo, A.; et al. The Flavonoid Quercetin Reverses Pulmonary Hypertension in Rats. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutliff, R.L.; Kang, B.Y.; Hart, C.M. Ppargamma as a Potential Therapeutic Target in Pulmonary Hypertension. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2010, 4, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Chen, R.; Wu, Y.; Huang, B.; Tang, C.; Chen, J.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Q.; Yang, J.; Qiu, H.; et al. Pparγ-Pi3k/Akt-No Signal Pathway Is Involved in Cardiomyocyte Hypertrophy Induced by High Glucose and Insulin. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2015, 29, 755–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, S.; Kobayashi, H.; Iwasa, M.; Kawamura, I.; Sumi, S.; Narentuoya, B.; Yamaki, T.; Ushikoshi, H.; Nishigaki, K.; Nagashima, K.; et al. Antidiabetic Drug Pioglitazone Protects the Heart Via Activation of Ppar-Gamma Receptors, Pi3-Kinase, Akt, and Enos Pathway in a Rabbit Model of Myocardial Infarction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009, 296, H1558–H1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinovitch, M. Ppargamma and the Pathobiology of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 661, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, K.; Tian, L.; Fu, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Lu, W.; Wang, J. Bmp4 Increases the Expression of Trpc and Basal [Ca2+]I Via the P38mapk and Erk1/2 Pathways Independent of Bmprii in Pasmcs. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.L.; Yu, J.; Taylor, L.; Polgar, P. Hyperplastic Growth of Pulmonary Artery Smooth Muscle Cells from Subjects with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Is Activated through Jnk and P38 Mapk. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, J.; Sun, L.; Shi, Y.; Wang, L.; Tao, W.; Cheng, D.; Wang, X.; Mi, Z.; et al. Regulating Inflammation Microenvironment and Tenogenic Differentiation as Sequential Therapy Promotes Tendon Healing in Diabetic Rats. J. Orthop. Transl. 2025, 53, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottolenghi, S.; Zulueta, A.; Caretti, A. Iron and Sphingolipids as Common Players of (Mal)Adaptation to Hypoxia in Pulmonary Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, C.C.; Dai, A.G. Expression of Mitogen-Actived Protein Kinase, Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase and Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α in Pulmonary Arteries of Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Chin. J. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2006, 29, 372–375. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.H.; Chen, Y.X.; Xue, G.; Yang, J.Y.; Wei, X.Y.; Zhang, G.X.; Qian, J.X. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Ameliorate Hypoxic Pulmonary Hypertension by Inhibiting the Hsp90aa1/Erk/Perk Pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 226, 116382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, H.H.; Chen, I.J.; Lo, Y.C. Effects of San-Huang-Xie-Xin-Tang on U46619-Induced Increase in Pulmonary Arterial Blood Pressure. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008, 117, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, H.; Brown, Z.; Burns, A.; Williams, T. Phosphodiesterase 5 Inhibitors for Pulmonary Hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 1, Cd012621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, K.J.; Lee, K.P.; Baek, S.; Cui, L.; Kweon, M.H.; Jung, S.H.; Ryu, Y.K.; Hong, J.M.; Cho, E.A.; Shin, H.S.; et al. Desalted Salicornia Europaea Extract Attenuated Vascular Neointima Formation by Inhibiting the Mapk Pathway-Mediated Migration and Proliferation in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 94, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerackody, R.P.; Welsh, D.J.; Wadsworth, R.M.; Peacock, A.J. Inhibition of P38 Mapk Reverses Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Artery Endothelial Dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009, 296, H1312–H1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotomalala, G.; Agard, C.; Tonnerre, P.; Tesse, A.; Derbré, S.; Michalet, S.; Hamzaoui, J.; Rio, M.; Cario-Toumaniantz, C.; Richomme, P.; et al. Extract from Mimosa Pigra Attenuates Chronic Experimental Pulmonary Hypertension. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 148, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenn, L.; Paper, D.H. Inhibition of Angiogenesis and Inflammation by an Extract of Red Clover (Trifolium Pratense L.). Phytomedicine 2009, 16, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammers, S.R.; Kao, P.H.; Qi, H.J.; Hunter, K.; Lanning, C.; Albietz, J.; Hofmeister, S.; Mecham, R.; Stenmark, K.R.; Shandas, R. Changes in the Structure-Function Relationship of Elastin and Its Impact on the Proximal Pulmonary Arterial Mechanics of Hypertensive Calves. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 295, H1451–H1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrão, R.; Costa, R.; Duarte, D.; Taveira Gomes, T.; Mendanha, M.; Moura, L.; Vasques, L.; Azevedo, I.; Soares, R. Angiogenesis and Inflammation Signaling Are Targets of Beer Polyphenols on Vascular Cells. J. Cell Biochem. 2010, 111, 1270–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.F.; Faria-Costa, G.; Sousa-Nunes, F.; Santos, M.F.; Ferreira-Pinto, M.J.; Duarte, D.; Rodrigues, I.; Tiago Guimarães, J.; Leite-Moreira, A.; Moreira-Gonçalves, D.; et al. Anti-Remodeling Effects of Xanthohumol-Fortified Beer in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Mediated by Erk and Akt Inhibition. Nutrients 2019, 11, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.; Yang, C.S.; Pickett, C.B. The Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms Regulating Nrf2 Activation in Response to Chemical Stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 37, 433–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Sherratt, P.J.; Huang, H.C.; Yang, C.S.; Pickett, C.B. Increased protein stability as a mechanism that enhances Nrf2-mediated transcriptional activation of the antioxidant response element. Degradation of Nrf2 by the 26 S proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 4536–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Zhang, K.; Mao, X.; Ding, X.; Zeng, Q.; Bai, S.; Xuan, Y.; Peng, H. Vanadate Oxidative and Apoptotic Effects Are Mediated by the Mapk-Nrf2 Pathway in Layer Oviduct Magnum Epithelial Cells. Metallomics 2017, 9, 1562–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladaileh, S.H.; Hussein, O.E.; Abukhalil, M.H.; Saghir, S.A.M.; Bin-Jumah, M.; Alfwuaires, M.A.; Germoush, M.O.; Almaiman, A.A.; Mahmoud, A.M. Formononetin Upregulates Nrf2/Ho-1 Signaling and Prevents Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Kidney Injury in Methotrexate-Induced Rats. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, W.; Lee, H.; Kim, N.; Jo, H.G.; Woo, E.R.; Lee, K.; Han, Y.S.; Park, S.R.; Ahn, G.; Cheong, S.H.; et al. The Anti-Oxidative and Anti-Neuroinflammatory Effects of Sargassum Horneri by Heme Oxygenase-1 Induction in Bv2 and Ht22 Cells. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ci, X.; Wen, Z.; Peng, L. Diosmetin Alleviates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Lung Injury through Activating the Nrf2 Pathway and Inhibiting the Nlrp3 Inflammasome. Biomol. Ther. 2018, 26, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.Y.; Ko, H.C.; Ko, S.Y.; Hwang, J.H.; Park, J.G.; Kang, S.H.; Han, S.H.; Yun, S.H.; Kim, S.J. Correlation between Flavonoid Content and the No Production Inhibitory Activity of Peel Extracts from Various Citrus Fruits. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 30, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Ohto, Y.; Yano, M.; Koshiba, T.; Koshimizu, K.; Tokuda, H.; Nishino, H.; Ohigashi, H. Suppressive Effects of Citrus Fruits on Free Radical Generation and Nobiletin, an Anti-Inflammatory Polymethoxyflavonoid. Biofactors 2000, 12, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Song, M.; Rakariyatham, K.; Zheng, J.; Guo, S.; Tang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Xiao, H. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of 4′-Demethylnobiletin, a Major Metabolite of Nobiletin. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 19, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkas, D.; Alhussaini, A.A.; Kraskauskas, D.; Kraskauskiene, V.; Cool, C.D.; Nicolls, M.R.; Natarajan, R.; Farkas, L. Nuclear Factor Κb Inhibition Reduces Lung Vascular Lumen Obliteration in Severe Pulmonary Hypertension in Rats. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014, 51, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Qiu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Z.; Lu, G.; Wang, L.; Kang, P.; Wang, H. Quercetin Improves Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension in Rats by Regulating the Hmgb1/Rage/Nf-Κb Pathway. J. South. Med. Univ. 2023, 43, 1606–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Dong, L.; Yang, Z.W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.L.; Niu, M.J.; Xia, J.W.; Gong, Y.; Zhu, N.; et al. Crosstalk between the Akt/Mtorc1 and Nf-Κb Signaling Pathways Promotes Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension by Increasing Dpp4 Expression in Pasmcs. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2019, 40, 1322–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Yang, L.; Dong, L.; Niu, M.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Z.; Wumaier, G.; Li, Y.; Wei, X.; Gong, Y.; et al. Cefminox, a Dual Agonist of Prostacyclin Receptor and Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-Gamma Identified by Virtual Screening, Has Therapeutic Efficacy against Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Hypertension in Rats. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameswaran, N.; Patial, S. Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Signaling in Macrophages. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 2010, 20, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milstone, D.S.; Ilyama, M.; Chen, M.; O’Donnell, P.; Davis, V.M.; Plutzky, J.; Brown, J.D.; Haldar, S.M.; Siu, A.; Lau, A.C.; et al. Differential Role of an Nf-Κb Transcriptional Response Element in Endothelial Versus Intimal Cell Vcam-1 Expression. Circ. Res. 2015, 117, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.S.; Hernandez Schulman, I.; Pagano, P.J.; Jaimes, E.A.; Raij, L. Reduced Nad(P)H Oxidase in Low Renin Hypertension: Link among Angiotensin Ii, Atherogenesis, and Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2006, 47, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, A.; Wang, H.; Zhou, M.S. Puerarin Protects against Endothelial Dysfunction and End-Organ Damage in Ang Ii-Induced Hypertension. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2017, 39, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Wang, A.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, M.S. Puerarin Improves Vascular Insulin Resistance and Cardiovascular Remodeling in Salt-Sensitive Hypertension. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2017, 45, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garat, C.V.; Crossno, J.T., Jr.; Sullivan, T.M.; Reusch, J.E.; Klemm, D.J. Inhibition of Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt Signaling Attenuates Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Artery Remodeling and Suppresses Creb Depletion in Arterial Smooth Muscle Cells. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2013, 62, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Bian, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Sun, R.; Li, G. Effect of Lemon Peel Flavonoids on Uvb-Induced Skin Damage in Mice. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 31470–31478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.H.; Alex, D.; Lam, I.K.; Tsui, S.K.; Yang, Z.F.; Lee, S.M. Nobiletin, a Polymethoxylated Flavonoid from Citrus, Shows Anti-Angiogenic Activity in a Zebrafish in Vivo Model and Huvec in Vitro Model. J. Cell Biochem. 2011, 112, 3313–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikumar, P.; Dong, Z.; Mikhailov, V.; Denton, M.; Weinberg, J.M.; Venkatachalam, M.A. Apoptosis: Definition, Mechanisms, and Relevance to Disease. Am. J. Med. 1999, 107, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, K.M.; Anderson, N.G. The Protein Kinase B/Akt Signalling Pathway in Human Malignancy. Cell Signal 2002, 14, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, B.D.; Cantley, L.C. Akt/Pkb Signaling: Navigating Downstream. Cell 2007, 129, 1261–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huertas, A.; Guignabert, C.; Barberà, J.A.; Bärtsch, P.; Bhattacharya, J.; Bhattacharya, S.; Bonsignore, M.R.; Dewachter, L.; Dinh-Xuan, A.T.; Dorfmüller, P.; et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelium: The Orchestra Conductor in Respiratory Diseases: Highlights from Basic Research to Therapy. Eur. Respir. J. 2018, 51, 1700745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, H.; Khalil, R.A. Mechanisms of Pulmonary Vascular Dysfunction in Pulmonary Hypertension and Implications for Novel Therapies. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2022, 322, H702–H724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chester, A.H.; Yacoub, M.H.; Moncada, S. Nitric Oxide and Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2017, 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feriel, B.; Alessandra, C.; Deborah, G.J.; Corinne, N.; Raphaël, T.; Mina, O.; Ali, A.; Jean-Baptiste, M.; Guillaume, F.; Julien, G.; et al. Exploring the Endothelin-1 Pathway in Chronic Thromboembolic Pulmonary Hypertension Microvasculopathy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, J.; Chen, H.; Fang, J.; Wu, S.; Jia, Z. Vascular Remodeling: The Multicellular Mechanisms of Pulmonary Hypertension. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.P.; Chan, S.W.; Chan, A.S.; Chen, S.L.; Ma, X.J.; Xu, H.X. Puerarin Decreases Serum Total Cholesterol and Enhances Thoracic Aorta Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Expression in Diet-Induced Hypercholesterolemic Rats. Life Sci. 2006, 79, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, N.K.; White, C.R.; Pozzo-Miller, L.; Zhou, F.; Constance, C.; Inoue, T.; Patel, R.P.; Parks, D.A. Dietary Flavonoid Quercetin Stimulates Vasorelaxation in Aortic Vessels. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 49, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y.J.; Hsu, H.H.; Chang, G.J.; Lin, S.H.; Chen, W.J.; Huang, C.C.; Pang, J.S. Prostaglandin E1 Attenuates Pulmonary Artery Remodeling by Activating Phosphorylation of Creb and the Pten Signaling Pathway. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9974, Correction in Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Li, X.; Guo, Z.; Cui, X.; Li, H.; Jin, C.; Zhang, X.; Guan, X. Puerarin Accelerates Re-Endothelialization in a Carotid Arterial Injury Model: Impact on Vasodilator Concentration and Vascular Cell Functions. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2013, 62, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhu, X.; Hu, N.; Zhang, X.; Sun, T.; Xu, J.; Bian, X. Baicalin Attenuates Angiotensin Ii-Induced Endothelial Dysfunction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 465, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Li, S.; Zhu, L.; Fang, S.H.; Chen, J.L.; Xu, Q.Q.; Li, H.Y.; Luo, N.C.; Yang, C.; Luo, D.; et al. Effect of Baicalin on Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation-Induced Endothelial Cell Damage. Neuroreport 2017, 28, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Lin, S.; Pu, Z.; Li, H.; Tang, Z. Protective Effects of Baicalin on Experimental Myocardial Infarction in Rats. Braz. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 33, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Yao, L.; Guo, L.; Jiang, Y.; Jin, H. Effect of Isoliquiritigenin on Hypoxia-Induced Pulmonary Artery Remodeling in Rats. Acta Anat. Sin. 2018, 49, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Imran, M.; Rauf, A.; Orhan, I.E.; Shariati, M.A.; Iahtisham Ul, H.; IqraYasmin; Shahbaz, M.; Qaisrani, T.B.; Shah, Z.A.; et al. Chrysin: Pharmacological and Therapeutic Properties. Life Sci. 2019, 235, 116797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, C. Advantage of a Micronized Flavonoidic Fraction (Daflon 500 Mg) in Comparison with a Nonmicronized Diosmin. Angiology 1994, 45, 531–536. [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier, P.; Karetova, D.; Gutierrez, L.R.; Maggioli, A. 19th Meeting of the Europeanvenous Forum: Athens, Greece. Phlebology 2018, 33, 702–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abstracts from the 38th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Hbprca. Hypertension 2017, 69, e23–e36. [CrossRef]

- Grassi, D.; Desideri, G.; De Feo, M.; Fellini, E.; Mai, F.; Dante, A.; Di Agostino, S.; Di Giosia, P.; Patrizi, F.; Martella, L.; et al. XXXI National Congress of the Italian Society of Hypertension (Siia) Selected Abstracts. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2014, 21, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engler, M.B.; Engler, M.M.; Chen, C.Y.; Malloy, M.J.; Browne, A.; Chiu, E.Y.; Kwak, H.K.; Milbury, P.; Paul, S.M.; Blumberg, J.; et al. Flavonoid-Rich Dark Chocolate Improves Endothelial Function and Increases Plasma Epicatechin Concentrations in Healthy Adults. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2004, 23, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, S.R.; Savadkouhi, N.; Ebrahimzadeh, M.A. Drug Design Strategies That Aim to Improve the Low Solubility and Poor Bioavailability Conundrum in Quercetin Derivatives. Expert. Opin. Drug Discov. 2023, 18, 1117–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribaudo, G.; Pagano, M.A.; Pavan, V.; Redaelli, M.; Zorzan, M.; Pezzani, R.; Mucignat-Caretta, C.; Vendrame, T.; Bova, S.; Zagotto, G. Semi-Synthetic Derivatives of Natural Isoflavones from Maclura Pomifera as a Novel Class of Pde-5a Inhibitors. Fitoterapia 2015, 105, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Wu, F.; Lu, S.; Lu, W.; Cao, J.; Cheng, F.; Ou, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, F.; Wu, G.; et al. Luteolin-Loaded Hyaluronidase Nanoparticles with Deep Tissue Penetration Capability for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Treatment. Small Methods 2025, 9, e2400980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.Y.; Cong, Y.J.; Wei, J.X.; Guo, B.L.; Liu, C.Y.; Liao, Y.H. Pulmonary Delivery of Icariin-Phospholipid Complex Prolongs Lung Retention and Improves Therapeutic Efficacy in Mice with Acute Lung Injury/Ards. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2024, 241, 113989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneef, J.; Chadha, R. Implication of Differential Surface Anisotropy on Biopharmaceutical Performance of Polymorphic Forms of Ambrisentan. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 3792–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galiè, N.; McLaughlin, V.V.; Rubin, L.J.; Simonneau, G. An Overview of the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1802148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

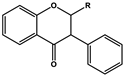

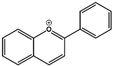

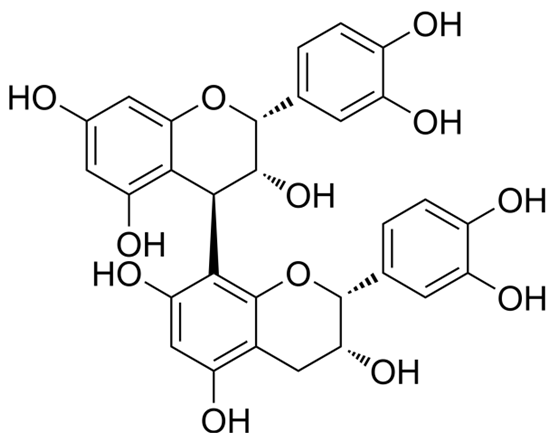

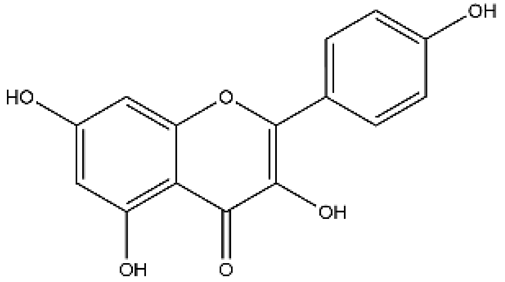

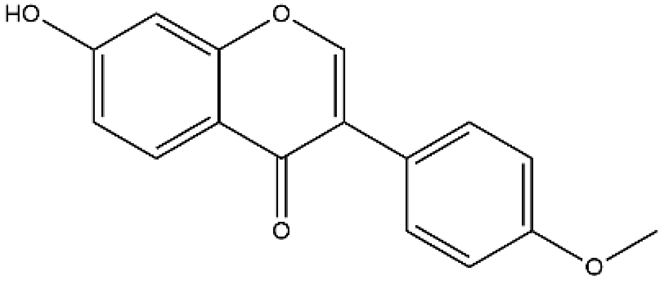

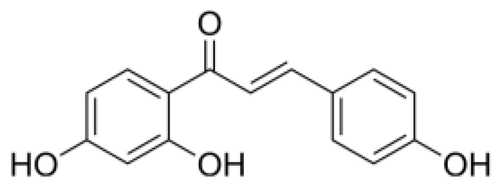

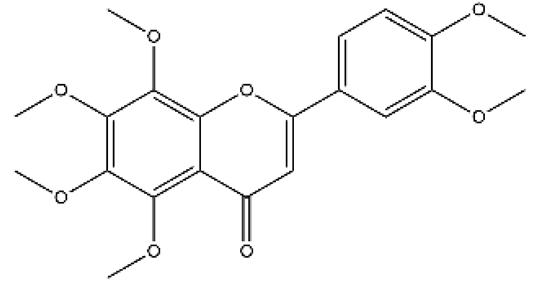

| Basic Parent Structure | |

|---|---|

| |

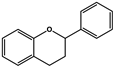

| Classification | |

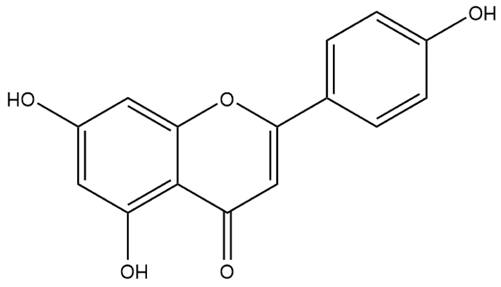

| Flavone (R=H) Flavonol (R=OH) |  |

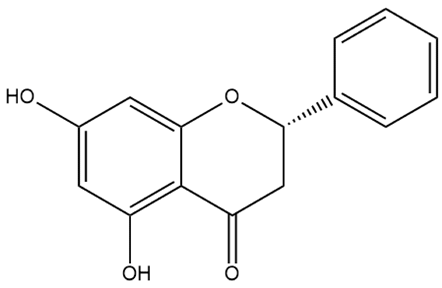

| Dihydroflavone (R=H) Dihydroflavonol (R=OH) |  |

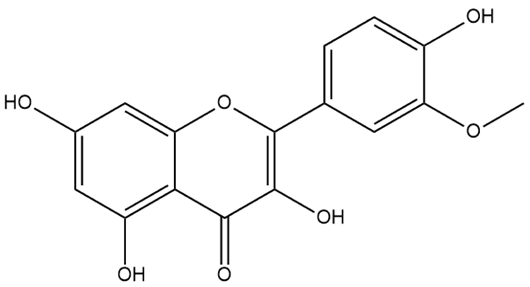

| Isoflavone (R=H) Isoflavonol (R=OH) |  |

| Dihydroisoflavone (R=H) Dihydroisoflavonol (R=OH) |  |

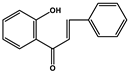

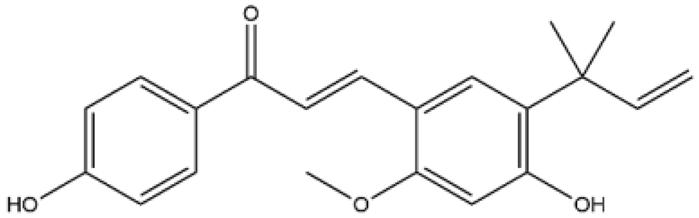

| Chalcones |  |

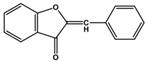

| Aurones |  |

| Flavanols |  |

| Anthocyanidins |  |

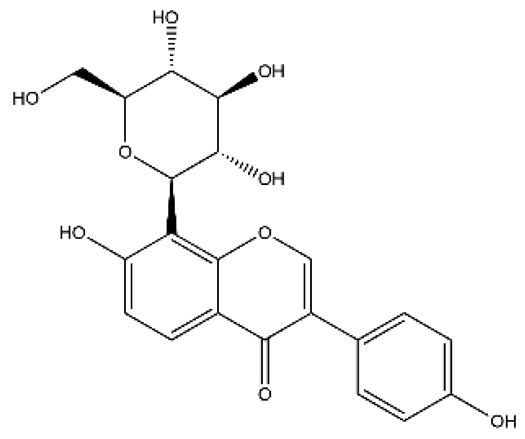

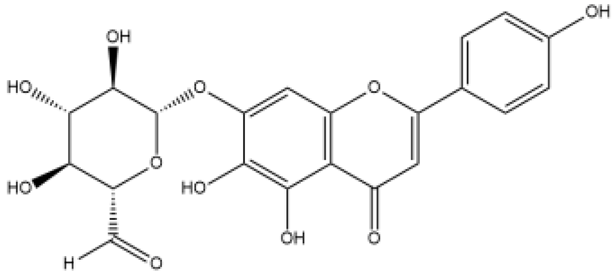

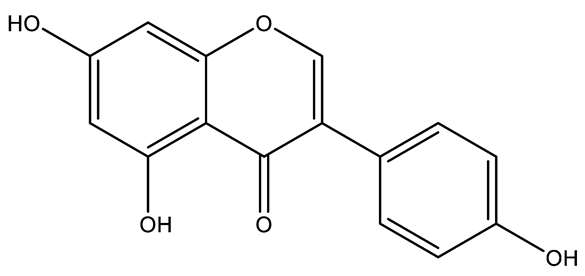

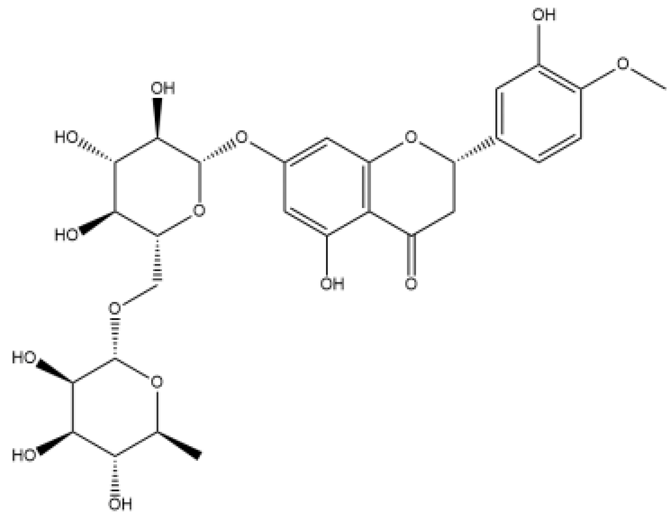

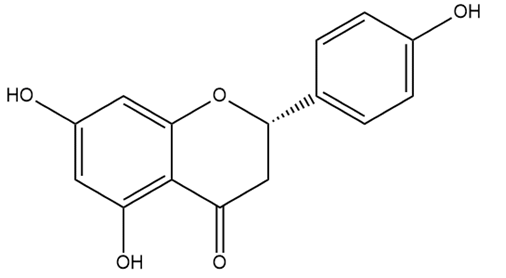

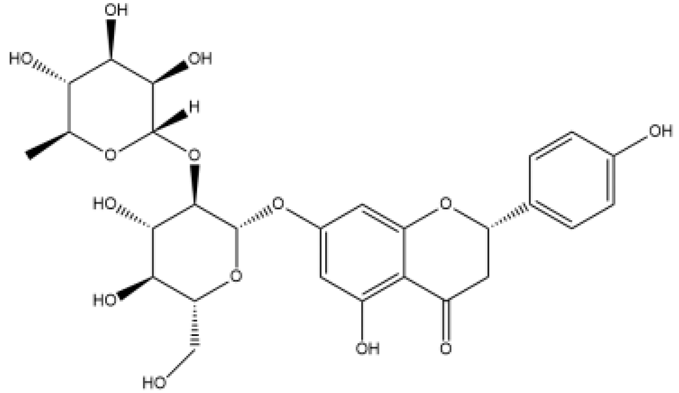

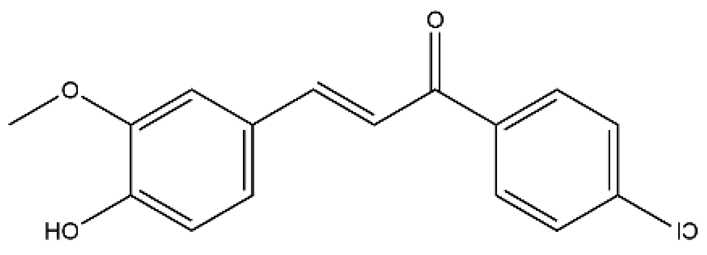

| Name | Classification | Structure | Model | Dose for PH Animals | Targets on Vascular Remodeling | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puerarin | Isoflavones |  | Monocrotaline (MCT) rats hypoxic pulmonary hypertension (HPH) mice/rats pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cell (PASMC), pulmonary artery endothelial cell (PAEC) cigarette smoke-exposed rats | p.o. 10–100 mg/kg/d i.p. 100 mg/kg/d | BMPR2/Smad, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt), protein kinase C (PKC) | [20,21,22,23,24] |

| Breviscapine | Flavone |  | HPH rats PASMC | p.o. 60 mg/kg/d | PKC, fractalkine | [25,26] |

| Genistein | Isoflavones |  | MCT rats HPH rats Low-temperature-induced PH in broiler chicks PAEC Isolated pulmonary artery | s.c. 20–200 μg, 1 mg/kg/d p.o. 20–60 mg/kg | PI3K/Akt/endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), estrogen receptor, β-adrenoceptor, erythropooietin/erythropoietin receptor, tyrosine kinases | [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] |

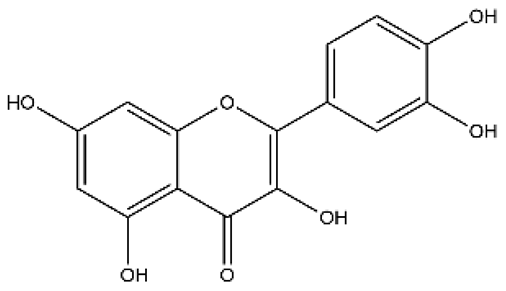

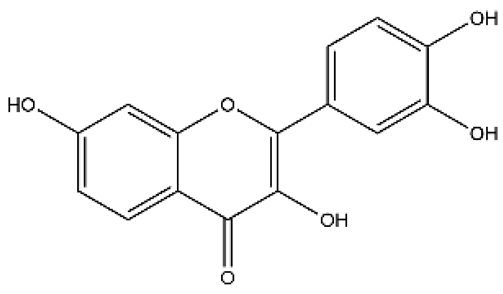

| Quercetin | Flavonol |  | MCT rats HPH rats PASMC PAEC | i.p. 30 mg/kg/d p.o. 100 mg/kg/d | Poly ADP-ribose polymerase-1, miR-204, inositol-requiring enzyme 1α, Akt/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2, forkhead box O1/mechanistic target of rapamycin, tropomyosin receptor kinase A | [26,34,35,36] |

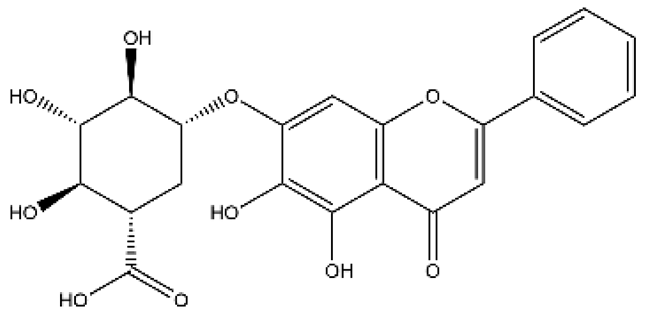

| Baicalin | Flavone |  | MCT rats HPH mice/rats PASMC PAEC | p.o. 25–100 mg/kg/d | calpain-1, PI3K/Akt/eNOS, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α, BMPR2, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), ERK, nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), Akt, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) | [37,38,39,40,41,42] |

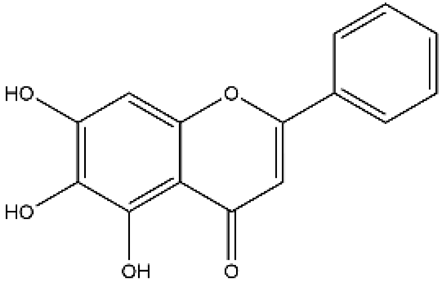

| Baicalein | Flavone |  | MCT rats Pneumonectomized rats PASMC | p.o. 50–100 mg/kg/d i.p. 10 mg/kg/d | NF-κB/BMPR2, endothelin (ET)-1/endothelin A receptor (ETAR), 12-lipoxygenase | [43,44,45,46] |

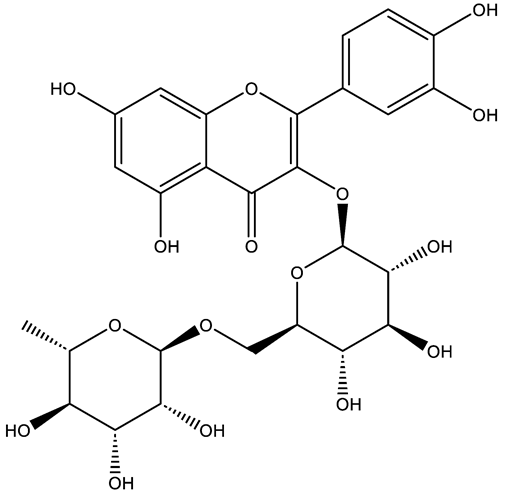

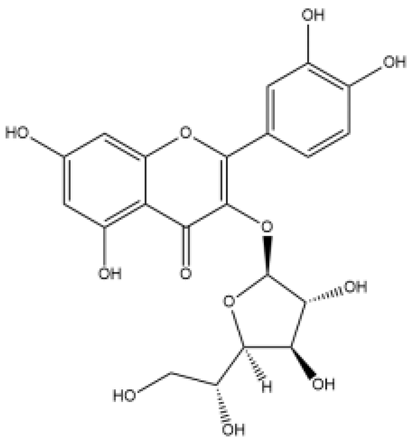

| Icariin | Flavonol |  | MCT rats | p.o. 20–100 mg/kg/d | TGFβ1, nitric oxide (NO)/cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) | [47,48] |

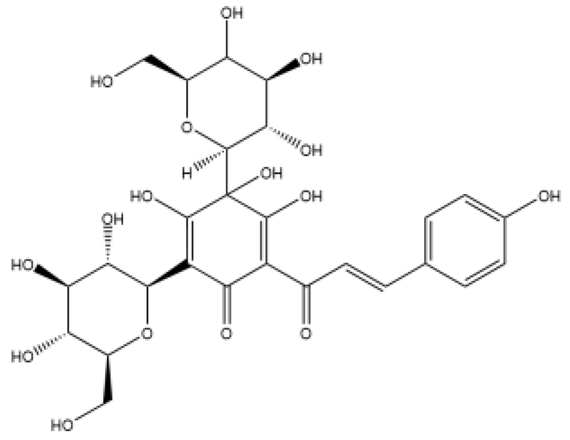

| Hydroxysafflor yellow A (Safflower Yellow) | Chalcones |  | MCT rats HPH rats PASMC | i.p. 10 mg/kg/d p.o. 25–100 mg/kg/d | voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channel, inhibit inflammation and oxidative stress | [49,50,51,52] |

| Rutin | Flavonol |  | MCT rats PASMC PAEC | p.o. 200 mg/kg/d | PKCα, NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) | [53,54] |

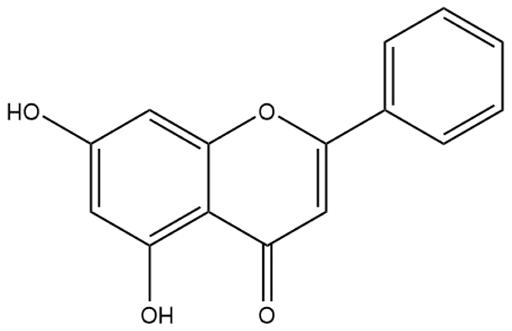

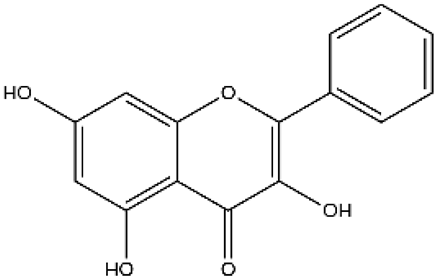

| Chrysin | Flavone |  | HPH rats MCT rats α-naphthylthiourea-PH rats PASMC | p.o. 10–100 mg/kg/d s.c. 50–100 mg/kg/d | Mitochondrial biogenesis, Ca2+ channel, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), eNOS, NOX4 | [55,56,57,58] |

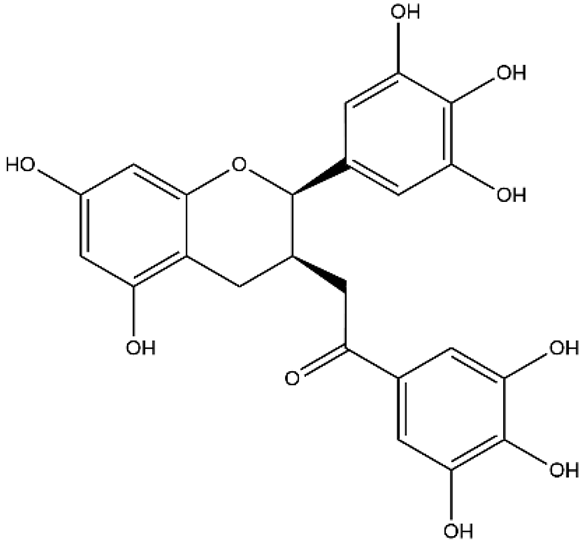

| Epigallocatechin gallate (catechins, EGCG) | Flavanol |  | HPH rats PASMC Aortic smooth muscle cell | p.o. 50–200 mg/kg/d | Krüppel-like Factor 4/mitofusin 2/p-ERK | [59,60,61] |

| Proanthocyanidins | Anthocyanidins |  | HPH rats MCT rats Cigarette-smoke-exposed rats PASMC | p.o. 250 mg/kg/d Endotracheal. 30 mg/kg | NOX4, PPARγ/cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), heat shock protein70, NF-κB | [62,63,64,65] |

| Luteolin | Flavone |  | MCT rats HPH rats PASMC PAEC | p.o. 50–100 mg/kg/d | Arachidonic acid metabolites, HIF2α, PI3K/Akt/eNOS | [66,67,68] |

| Kaempferol | Flavonol |  | HPH rats MCT rats Isolated pulmonary artery | p.o. 25–150 mg/kg/d i.p. 150 mg/kg | Akt/glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β)/cyclin, Arachidonic acid metabolites; Direct vasorelaxation effects | [69,70,71] |

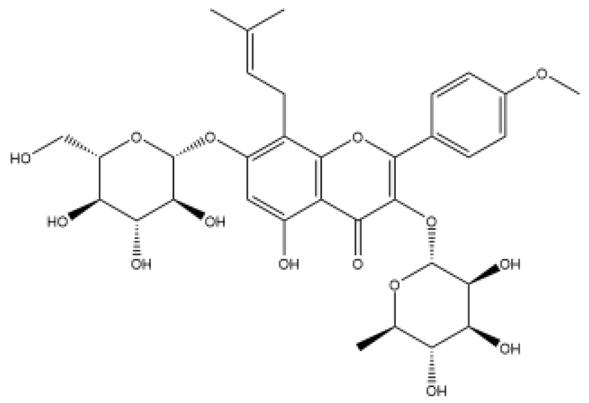

| Formononetin | Isoflavones |  | MCT rats Aortic smooth muscle cell | 10–60 mg/kg/d | ERK, NF-κB, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) | [72,73] |

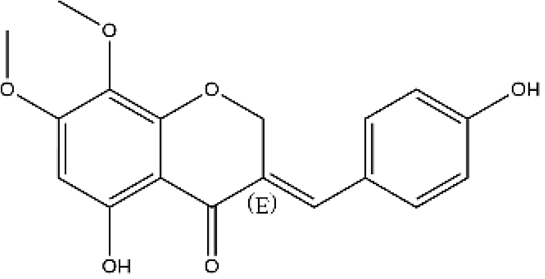

| Isoliquiritigenin | Chalcones |  | MCT rats | p.o. 10–20 mg/kg/d | Inhibit inflammation and proliferation | [74] |

| Apigenin | Flavone |  | HPH rats PASMC | p.o. 50–100 mg/kg/d | HIF1α/Kv1.5 | [75] |

| Pinocembrin | Dihydroflavone |  | MCT rats | i.p. 50 mg/kg/d | Improves the therapeutic efficacy of endothelial progenitor cells in PH rats; inhibits atrial fibrillation | [76,77] |

| Isorhamnetin | Flavonol |  | MCT rats PASMC | p.o. 50–150 mg/kg/d | BMPR2 | [78] |

| Wogonin | Flavone |  | PASMC | - | HIF1/NOX4 | [79,80] |

| Isoquercitrin | Flavonol |  | MCT rats PASMC | 0.1% in feed for 3 weeks | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor β | [74] |

| Hesperidin | Dihydroflavone |  | PASMC | - | Akt/GSK3β | [81] |

| Naringenin | Flavanones |  | MCT rats | p.o. 50 mg/kg/d | Adds to the protective effect of L-arginine in PH rats | [82] |

| Naringin | Flavanones |  | MCT rats PASMC | p.o. 25–100 mg/kg/d | ERK, NF-κB | [68] |

| Chalcone 4 | Chalcones |  | MCT rats HPH rats PASMC Pulmonary pericyte | i.p. 100 mg/kg/d | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 | [83] |

| Dihydromyricetin | Flavanonols |  | MCT rats PASMC | p.o. 100 mg/kg/d | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)/matrix metallopeptidase (MMP)-9, interleukin-6 (IL-6) | [84] |

| Nobiletin | Flavone |  | MCT rats | p.o. 1–10 mg/kg | PI3K/Akt/STAT3 | [85] |

| Name | Classification | Structure | Model | Dose for Animals | Targets on Vascular Remodeling | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|