Interplay Among Gut Microbiota-Derived TMAO, Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction, and Heart Failure Progression

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. ANS in HF

Direct Electrical Stimulation of the Vagus Nerve

3. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide

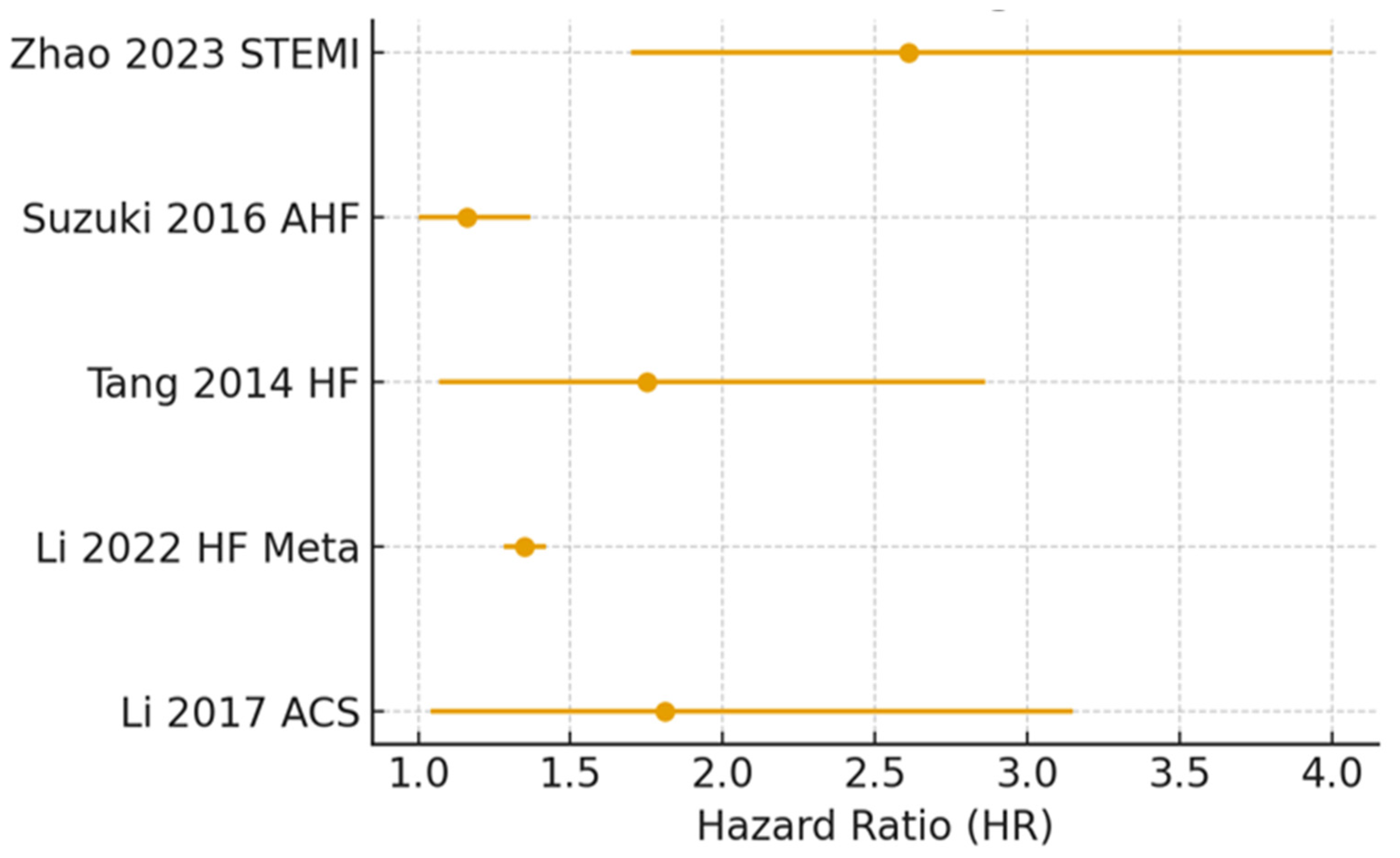

TMAO in Heart Failure

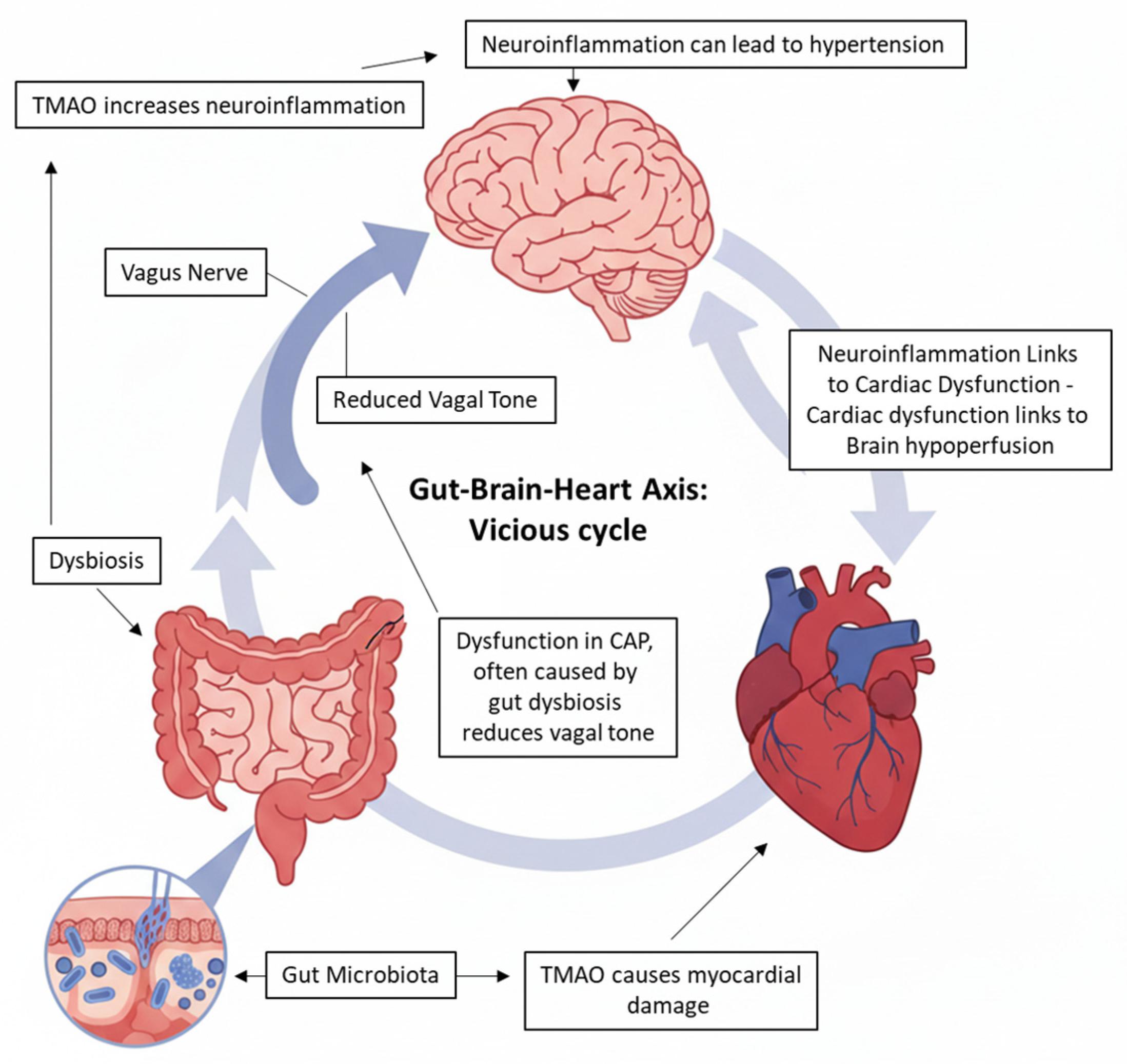

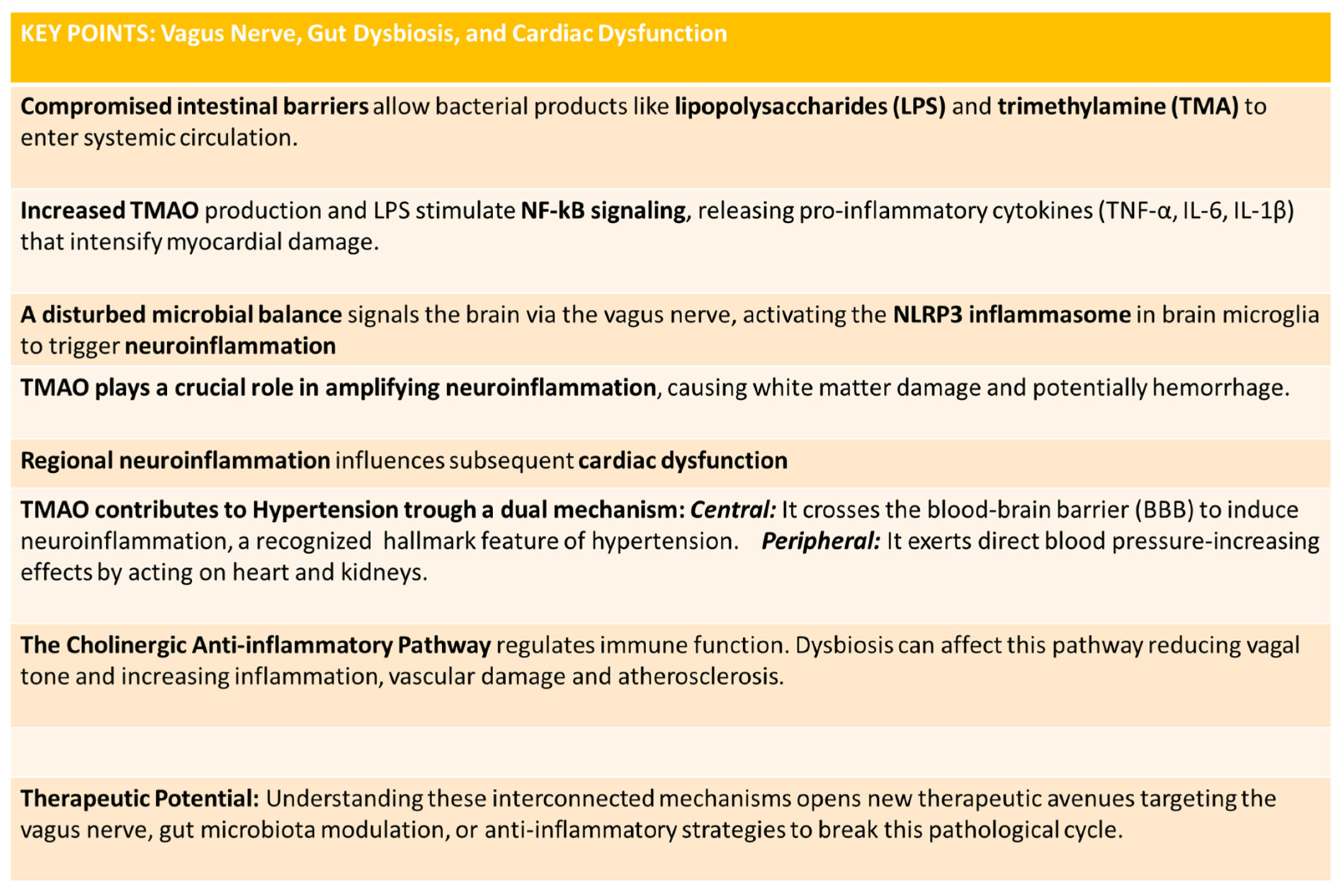

4. Link Among Vagus Nerve, Gut Dysbiosis, and Cardiac Dysfunction

4.1. The Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway and Gut Dysbiosis

4.2. The Gut–Brain Axis, Dysbiosis, and Neuroinflammation

4.3. TMAO: A Molecular Link to Cerebral and Cardiac Damage

4.4. The Vicious Cycle: Intracerebral Hemorrhage and Cardiac Dysfunction

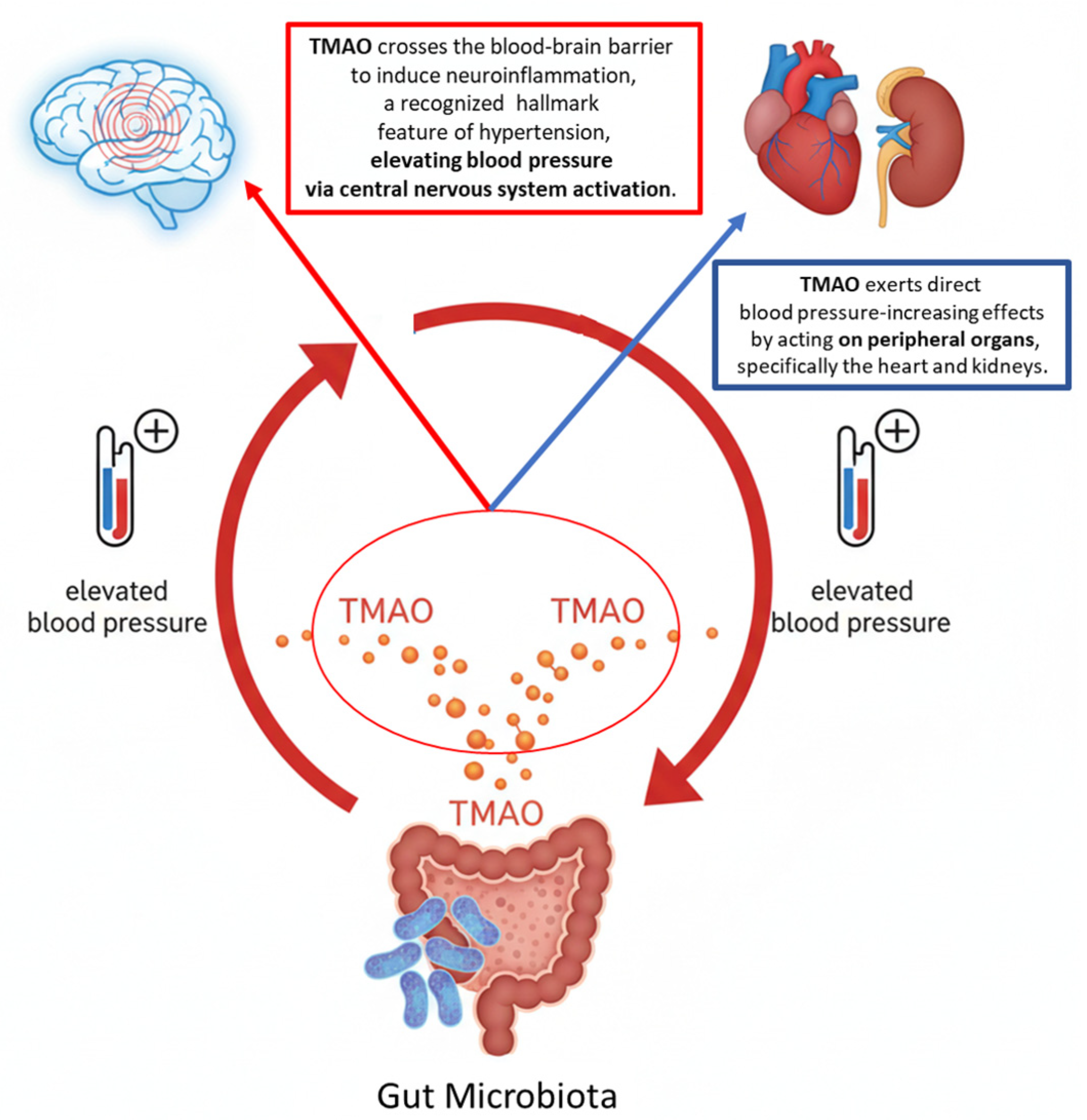

4.5. TMAO and Hypertension: A Dual Mechanism of Action

4.6. The Vagus Nerve and Autonomic Imbalance in Heart Failure

4.7. Cellular Mechanisms of TMAO Pathogenicity

5. Advanced In Vitro Platforms for Modeling the Gut–Brain–Heart Axis

- The Chip Level. Microfluidic devices containing hair-fine microchannels (tens to hundreds of micrometers) guide and manipulate picoliter-to-milliliter solution volumes [89]. These channels, etched or molded onto substrates like Polydimethylsiloxane or glass, enable high-precision experiments and biological assays at reduced scale.

- The Microfluidic Level. Scaffold-free cellular spheroids (e.g., iPSC-derived) of micrometer dimensions grow three-dimensionally at the base of 1.5 mL tubes with ≤1 mL medium. This system provides physiologically relevant conditions for genetic studies when transgenic models are unavailable, ensuring proper cell–cell contact across all surfaces [90].

- The Millifluidic Level. Coin-sized bioreactors support 2D/3D cell cultures (micro- to millimetric scale) with ~10 mL medium volumes and flow systems mimicking physiological circulation. These platforms investigate laminar flow, shear stress effects, and nonlinear dynamics, proving useful for modeling organ physiopathology, inter-organ communication, and disease conditions [91,92].

6. Therapeutic Directions

Pharmacological Interventions

- Statins:

- Diuretics of the loop of Henle:

- Nutraceuticals:

7. Conclusions and Future Therapeutic Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TMA | Trimethylamine |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine-N-oxide |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| CAP | Cholinergic Anti-inflammatory Pathway |

| FMO3 | Flavin monooxygenase-3 |

| FMO1 | Flavin monooxygenase-1 |

| NLRP3 | Nod-like Receptor Pyrin Domain-containing 3 |

| ANS | Autonomic Nervous System |

| ATRAMI | Autonomic Tone and Reflexes After Myocardial Infarction |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| NGF | Nerve Growth Factor |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| IL-18 | Interleukin-18 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis factor-α |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells |

References

- Caradonna, E.; Abate, F.; Schiano, E.; Paparella, F.; Ferrara, F.; Vanoli, E.; Difruscolo, R.; Goffredo, V.; Amato, B.; Setacci, C.; et al. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (TMAO) as a Rising-Star Metabolite: Implications for Human Health. Metabolites 2025, 15, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugham, M.; Bellanger, S.; Leo, C.H. Gut-Derived Metabolite, Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) in Cardio-Metabolic Diseases: Detection, Mechanism, and Potential Therapeutics. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saaoud, F.; Liu, L.; Xu, K.; Cueto, R.; Shao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Snyder, N.W.; Wu, S.; Yang, L.; et al. Aorta- and liver-generated TMAO enhances trained immunity for increased inflammation via ER stress/mitochondrial ROS/glycolysis pathways. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e158183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganapathy, T.; Yuan, J.; Ho, M.Y.; Wu, K.K.; Hoque, M.M.; Wang, B.; Li, X.; Wang, K.; Wabitsch, M.; Feng, X.; et al. Adipocyte FMO3-derived TMAO induces WAT dysfunction and metabolic disorders by promoting inflammasome activation in ageing. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 8873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martelli, A.; Abate, F.; Roggia, M.; Benedetti, G.; Caradonna, E.; Calderone, V.; Tenore, G.C.; Cosconati, S.; Novellino, E.; Stornaiuolo, M. Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) Acts as Inhibitor of Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase (eNOS) and Hampers NO Production and Acetylcholine-Mediated Vasorelaxation in Rat Aortas. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, M.; De Hert, M.; Detraux, J.; Di Palo, K.; Munir, H.; Music, S.; Piña, I.; Ringen, P.A. Severe Mental Illness and Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 80, 918–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, H.; Deaton, C.; Farrero, M.; Forsyth, F.; Braunschweig, F.; Buccheri, S.; Dragan, S.; Gevaert, S.; Held, C.; Kurpas, D.; et al. 2025 ESC Clinical Consensus Statement on mental health and cardiovascular disease: Developed under the auspices of the ESC Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 4156–4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, V.G.; Cohn, J.N. The Autonomic Nervous System and Heart Failure. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 1815–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddoura, R.; Madurasinghe, V.; Chapra, A.; Abushanab, D.; Al-Badriyeh, D.; Patel, A. Beta-blocker therapy in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (B-HFpEF): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2024, 49, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24, 4–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovere, M.T.L.; Bigger, J.T., Jr.; Marcus, F.I.; Mortara, A.; Schwartz, P.J. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. Lancet 1998, 351, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanoli, E.; Adamson, P.B. Baroreflex Sensitivity: Methods, Mechanisms, and Prognostic Value. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 1994, 17, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, P.B.; Vanoli, E. Early autonomic and repolarization abnormalities contribute to lethal arrhythmias in chronic ischemic heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 1741–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, P.J.; La Rovere, M.T.; Vanoli, E. Autonomic nervous system and sudden cardiac death. Experimental basis and clinical observations for post-myocardial infarction risk stratification. Circulation 1992, 85, I77–I91. [Google Scholar]

- Waagstein, F.; Hjalmarson, A.; Varnauskas, E.; Wallentin, I. Effect of chronic beta-adrenergic receptor blockade in congestive cardiomyopathy. Heart 1975, 37, 1022–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govoni, S.; Pascale, A.; Amadio, M.; Calvillo, L.; D’Elia, E.; Cereda, C.; Fantucci, P.; Ceroni, M.; Vanoli, E. NGF and heart: Is there a role in heart disease? Pharmacol. Res. 2011, 63, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Elia, E.; Pascale, A.; Marchesi, N.; Ferrero, P.; Senni, M.; Govoni, S.; Gronda, E.; Vanoli, E. Novel approaches to the post-myocardial infarction/heart failure neural remodeling. Heart Fail. Rev. 2014, 19, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, M.; Caporali, A.; Graiani, G.; Lagrasta, C.; Katare, R.; Van Linthout, S.; Spillmann, F.; Campesi, I.; Madeddu, P.; Quaini, F.; et al. Nerve growth factor promotes cardiac repair following myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 2010, 106, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, W.W.; Verrier, R.L.; Lown, B. Influence of autonomic nervous system stimulation on the protective zone. Cardiovasc. Res. 1981, 15, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanoli, E.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Stramba-Badiale, M.; Hull, S.S.; Foreman, R.D.; Schwartz, P.J. Vagal stimulation and prevention of sudden death in conscious dogs with a healed myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 1991, 68, 1471–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo, L.; Vanoli, E.; Andreoli, E.; Besana, A.; Omodeo, E.; Gnecchi, M.; Zerbi, P.; Vago, G.; Busca, G.; Schwartz, P.J. Vagal Stimulation, Through its Nicotinic Action, Limits Infarct Size and the Inflammatory Response to Myocardial Ischemia and Reperfusion. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2011, 58, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Oro, R.; Gronda, E.; Seravalle, G.; Costantino, G.; Alberti, L.; Baronio, B.; Staine, T.; Vanoli, E.; Mancia, G.; Grassi, G. Restoration of normal sympathetic neural function in heart failure following baroreflex activation therapy: Final 43-month study report. J. Hypertens. 2017, 35, 2532–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austelle, C.W.; O’Leary, G.H.; Thompson, S.; Gruber, E.; Kahn, A.; Manett, A.J.; Short, B.; Badran, B.W. A Comprehensive Review of Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Depression. Neuromodul. J. Int. Neuromodul. Soc. 2022, 25, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennema, D.; Phillips, I.R.; Shephard, E.A. Trimethylamine and Trimethylamine N-Oxide, a Flavin-Containing Monooxygenase 3 (FMO3)-Mediated Host-Microbiome Metabolic Axis Implicated in Health and Disease. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016, 44, 1839–1850, Erratum in Drug Metab Dispos. 2016, 44, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, D.; Janmohamed, A.; Chandan, P.; Phillips, I.R.; Shephard, E.A. Organization and evolution of the flavin-containing monooxygenase genes of human and mouse: Identification of novel gene and pseudogene clusters. Pharmacogenetics 2004, 14, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Leyrolle, Q.; Koistinen, V.; Kärkkäinen, O.; Layé, S.; Delzenne, N.; Hanhineva, K. Microbiota-derived metabolites as drivers of gut–brain communication. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2102878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, B.J.; Vallim, T.Q.d.A.; Wang, Z.; Shih, D.M.; Meng, Y.; Gregory, J.; Allayee, H.; Lee, R.; Graham, M.; Crooke, R.; et al. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide, a Metabolite Associated with Atherosclerosis, Exhibits Complex Genetic and Dietary Regulation. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartiala, J.; Bennett, B.J.; Tang, W.H.W.; Wang, Z.; Stewart, A.F.R.; Roberts, R.; McPherson, R.; Lusis, A.J.; Hazen, S.L.; Allayee, H. Comparative Genome-Wide Association Studies in Mice and Humans for Trimethylamine N-Oxide, a Proatherogenic Metabolite of Choline and l-Carnitine. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 1307–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradonna, E.; Nemni, R.; Bifone, A.; Gandolfo, P.; Costantino, L.; Giordano, L.; Mormone, E.; Macula, A.; Cuomo, M.; Difruscolo, R.; et al. The Brain–Gut Axis, an Important Player in Alzheimer and Parkinson Disease: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancey, P.H. Water Stress, Osmolytes and Proteins. Am. Zool. 2001, 41, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yancey, P.H. Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO): A Unique Counteracting Osmolyte? Paracelsus Proc. Exp. Med. 2023, 2, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, K.; Warepam, M.; Bansal, A.K.; Dar, T.A.; Uversky, V.N.; Singh, L.R. The gut metabolite, trimethylamine N-oxide inhibits protein folding by affecting cis–trans isomerization and induces cell cycle arrest. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniam, S.; Fletcher, C. Trimethylamine N-oxide: Breathe new life. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falony, G.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Raes, J. Microbiology Meets Big Data: The Case of Gut Microbiota–Derived Trimethylamine. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 69, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoyles, L.; Jiménez-Pranteda, M.L.; Chilloux, J.; Brial, F.; Myridakis, A.; Aranias, T.; Magnan, C.; Gibson, G.R.; Sanderson, J.D.; Nicholson, J.K.; et al. Metabolic retroconversion of trimethylamine N-oxide and the gut microbiota. Microbiome 2018, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jameson, E.; Doxey, A.C.; Airs, R.; Purdy, K.J.; Murrell, J.C.; Chen, Y. Metagenomic data-mining reveals contrasting microbial populations responsible for trimethylamine formation in human gut and marine ecosystems. Microb. Genom. 2016, 2, e000080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Klipfell, E.; Bennett, B.J.; Koeth, R.; Levison, B.S.; DuGar, B.; Feldstein, A.E.; Britt, E.B.; Fu, X.; Chung, Y.-M.; et al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature 2011, 472, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bergeron, N.; Levison, B.S.; Li, X.S.; Chiu, S.; Jia, X.; Koeth, R.A.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Tang, W.H.W.; et al. Impact of chronic dietary red meat, white meat, or non-meat protein on trimethylamine N-oxide metabolism and renal excretion in healthy men and women. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.S.; Obeid, S.; Klingenberg, R.; Gencer, B.; Mach, F.; Räber, L.; Windecker, S.; Rodondi, N.; Nanchen, D.; Muller, O.; et al. Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide in acute coronary syndromes: A prognostic marker for incident cardiovascular events beyond traditional risk factors. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 814–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heianza, Y.; Ma, W.; DiDonato, J.A.; Sun, Q.; Rimm, E.B.; Hu, F.B.; Rexrode, K.M.; Manson, J.E.; Qi, L. Long-Term Changes in Gut Microbial Metabolite Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Coronary Heart Disease Risk. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heianza, Y.; Ma, W.; Manson, J.E.; Rexrode, K.M.; Qi, L. Gut Microbiota Metabolites and Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Disease Events and Death: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e004947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, C.I.; Vallejo, J.A.; Wang, D.; Gray, M.A.; Tiede-Lewis, L.M.; Shawgo, T.; Daon, E.; Zorn, G.; Stubbs, J.R.; Wacker, M.J. Trimethylamine-N-oxide acutely increases cardiac muscle contractility. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 318, H1272–H1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Heaney, L.M.; Bhandari, S.S.; Jones, D.J.L.; Ng, L.L. Trimethylamine N-oxide and prognosis in acute heart failure. Heart 2016, 102, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Wang, Z.; Fan, Y.; Levison, B.; Hazen, J.E.; Donahue, L.M.; Wu, Y.; Hazen, S.L. Prognostic Value of Elevated Levels of Intestinal Microbe-Generated Metabolite Trimethylamine-N-Oxide in Patients With Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 1908–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Yazaki, Y.; Voors, A.A.; Jones, D.J.L.; Chan, D.C.S.; Anker, S.D.; Cleland, J.G.; Dickstein, K.; Filippatos, G.; Hillege, H.L.; et al. Association with outcomes and response to treatment of trimethylamine N-oxide in heart failure: Results from BIOSTAT-CHF. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisci, G.; Israr, M.Z.; Cittadini, A.; Bossone, E.; Suzuki, T.; Salzano, A. Heart failure and trimethylamine N-oxide: Time to transform a ‘gut feeling’ in a fact? ESC Heart Fail. 2023, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzano, A.; Cassambai, S.; Yazaki, Y.; Israr, M.Z.; Bernieh, D.; Wong, M.; Suzuki, T. The Gut Axis Involvement in Heart Failure. Cardiol. Clin. 2022, 40, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, P.; Li, S.; Gao, Y.; Xing, Y. From heart failure and kidney dysfunction to cardiorenal syndrome: TMAO may be a bridge. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1291922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lu, H.; Guo, J.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W. Gut microbiota-derived trimethylamine N-oxide is associated with the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2215542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrikopoulos, P.; Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Chakaroun, R.; Myridakis, A.; Forslund, S.K.; Nielsen, T.; Adriouch, S.; Holmes, B.; Chilloux, J.; Vieira-Silva, S.; et al. Evidence of a causal and modifiable relationship between kidney function and circulating trimethylamine N-oxide. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Meng, G.; Huang, B.; Zhou, X.; Stavrakis, S.; Wang, M.; Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; et al. A potential relationship between gut microbes and atrial fibrillation: Trimethylamine N-oxide, a gut microbe-derived metabolite, facilitates the progression of atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 255, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.-T.; Yang, R.; Zhao, Q.; Li, X.-D.; Wang, Y.-T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the gut microbiota-dependent metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide with the incidence of atrial fibrillation. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 11512–11523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendtzen, K. Are microbiomes involved in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation? Repeated clinical improvement after pivmecillinam (amdinocillin) therapy. Acad. Lett. 2021, Article 3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, G.; Zhou, X.; Wang, M.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, M.; Deng, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Gut microbe-derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide activates the cardiac autonomic nervous system and facilitates ischemia-induced ventricular arrhythmia via two different pathways. eBioMedicine 2019, 44, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fan, Z.; Cui, J.; Li, D.; Lu, J.; Cui, X.; Xie, L.; Wu, Y.; Lin, Q.; Li, Y. Trimethylamine N-Oxide in Heart Failure: A Meta-Analysis of Prognostic Value. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 817396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Tian, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, F.; Xu, J.; Qin, Z.; Liu, X.; Cao, M.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, G.; et al. Prognostic value of gut microbiota-derived metabolites in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 117, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, K.J. The inflammatory reflex. Nature 2002, 420, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Ji, C.; Gu, S.; Yin, Q.; Zuo, J. The Role of α7nAChR-Mediated Cholinergic Anti-inflammatory Pathway in Immune Cells. Inflammation 2021, 44, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.S.; Katz, D.A.; Rosas-Ballina, M.; Levine, Y.A.; Ochani, M.; Valdés-Ferrer, S.I.; Pavlov, V.A.; Tracey, K.J.; Chavan, S.S. α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor (α7nAChR) Expression in Bone Marrow-Derived Non-T Cells Is Required for the Inflammatory Reflex. Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huston, J.M.; Tracey, K.J. The pulse of inflammation: Heart rate variability, the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway and implications for therapy: Symposium: The pulse of inflammation: Implications for therapy. J. Intern. Med. 2011, 269, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alen, N.V. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway in humans: State-of-the-art review and future directions. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 136, 104622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracey, K.J. Physiology and immunology of the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlov, V.; Wang, H.; Czura, C.J.; Friedman, S.G.; Tracey, K.J. The Cholinergic Anti-inflammatory Pathway: A Missing Link in Neuroimmunomodulation. Mol. Med. 2003, 9, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.-J.; Evans, R.G.; Yang, Z.-W.; Song, S.-W.; Wang, P.; Ma, X.-J.; Liu, C.; Xi, T.; Su, D.-F.; Shen, F.-M. Dysfunction of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway mediates organ damage in hypertension. Hypertension 2011, 57, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trehan, S.; Singh, G.; Bector, G.; Jain, P.; Mehta, T.; Goswami, K.; Chawla, A.; Jain, A.; Puri, P.; Garg, N. Gut Dysbiosis and Cardiovascular Health: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Cureus 2024, 16, e67010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesci, A.; Carnuccio, C.; Ruggieri, V.; D’Alessandro, A.; Di Giorgio, A.; Santoro, L.; Gasbarrini, A.; Santoliquido, A.; Ponziani, F.R. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence on the Metabolic and Inflammatory Background of a Complex Relationship. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttiah, B.; Hanafiah, A. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Diseases: Unraveling the Role of Dysbiosis and Microbial Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, X.; Fang, Q.; Yin, X. Gut Microbe-Generated Metabolite Trimethylamine-N-Oxide and Ischemic Stroke. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, W.A. The blood-brain barrier in neuroimmunology: Tales of separation and assimilation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, M.; Rapetti, F.; Spallarossa, A.; Brullo, C. PDE4D: A Multipurpose Pharmacological Target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Cai, X.; Xie, Q.; Xiao, X.; Li, T.; Zhou, T.; Sun, H. NLRP3 inflammasome and gut microbiota–brain axis: A new perspective on white matter injury after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neural Regen. Res. 2026, 21, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buletko, A.B.; Thacker, T.; Cho, S.-M.; Mathew, J.; Thompson, N.R.; Organek, N.; Frontera, J.A.; Uchino, K. Cerebral ischemia and deterioration with lower blood pressure target in intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology 2018, 91, e1058–e1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermanns, N.; Wroblewski, V.; Bascuñana, P.; Wolf, B.; Polyak, A.; Ross, T.L.; Bengel, F.M.; Thackeray, J.T. Molecular imaging of the brain–heart axis provides insights into cardiac dysfunction after cerebral ischemia. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2022, 117, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shourav, M.M.I.; Godasi, R.R.; Anisetti, B.; English, S.W.; Lyle, M.A.; Huang, J.F.; Meschia, J.F.; Lin, M.P. Association between heart failure and cerebral collateral flow in large vessel occlusive ischemic stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2024, 33, 107999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, K.; Kornej, J.; Shantsila, E.; Lip, G.Y.H. Heart Failure and Stroke. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2018, 15, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo, L.; Gironacci, M.M.; Crotti, L.; Meroni, P.L.; Parati, G. Neuroimmune crosstalk in the pathophysiology of hypertension. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019, 16, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Wang, P.X.; Mei, X.; Yang, T.; Yu, K. Untapped potential of gut microbiome for hypertension management. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2356278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.-B.; Powley, T.L. Vagal innervation of intestines: Afferent pathways mapped with new en bloc horseradish peroxidase adaptation. Cell Tissue Res. 2007, 329, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wang, F.; Gao, L.; Wang, Y. Trimethylamine oxide promotes myocardial fibrosis through activating JAK2-STAT3 pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 750, 151390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, E.; Campbell, M.; Doyle, S. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in chronic inflammatory diseases: Current perspectives. J. Inflamm. Res. 2015, 8, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, Q.; Jiang, H. Gut microbiota in atherosclerosis: Focus on trimethylamine N-oxide. APMIS 2020, 128, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muslin, A.J. MAPK signalling in cardiovascular health and disease: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Clin. Sci. 2008, 115, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, P.; Duan, H.; Tao, C.; Niu, S.; Hu, Y.; Duan, R.; Shen, A.; Sun, Y.; Sun, W. TMAO Promotes NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation of Microglia Aggravating Neurological Injury in Ischemic Stroke Through FTO/IGF2BP2. J. Inflamm. Res. 2023, 16, 3699–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hage, R.; Al-Arawe, N.; Hinterseher, I. The Role of the Gut Microbiome and Trimethylamine Oxide in Atherosclerosis and Age-Related Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Zeng, L.; Shi, J.; Chen, Y. Trimethylamine N-oxide Promotes Atherosclerosis by Regulating Low-Density Lipoprotein-Induced Autophagy in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Through PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway. Int. Heart J. 2023, 64, 462–469, Erratum in Int. Heart J. 2023, 64, 789. https://doi.org/10.1536/ihj.64-4_Errata. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhu, X.; Ran, L.; Lang, H.; Yi, L.; Mi, M. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Induces Vascular Inflammation by Activating the NLRP3 Inflammasome Through the SIRT3-SOD2-mtROS Signaling Pathway. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e006347, Erratum in J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e002238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannenbaum, J.; Bennett, B.T. Russell and Burch’s 3Rs then and now: The need for clarity in definition and purpose. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2015, 54, 120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Puschhof, J.; Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C.; Clevers, H. Organoids and organs-on-chips: Insights into human gut-microbe interactions. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 867–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.M.; de Haan, P.; Ronaldson-Bouchard, K.; Kim, G.-A.; Ko, J.; Rho, H.S.; Chen, Z.; Habibovic, P.; Jeon, N.L.; Takayama, S.; et al. A guide to the organ-on-a-chip. Nat. Rev. Methods Primer 2022, 2, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, P.; Moritz, W.; Kelm, J.M.; Ullrich, N.D.; Agarkova, I.; Anson, B.D.; Suter, T.M.; Zuppinger, C. Development and Characterization of a Scaffold-Free 3D Spheroid Model of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Human Cardiomyocytes. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2015, 21, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesi, N.; Barbieri, A.; Fahmideh, F.; Govoni, S.; Ghidoni, A.; Parati, G.; Vanoli, E.; Pascale, A.; Calvillo, L. Use of dual-flow bioreactor to develop a simplified model of nervous-cardiovascular systems crosstalk: A preliminary assessment. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giusti, S.; Sbrana, T.; La Marca, M.; Di Patria, V.; Martinucci, V.; Tirella, A.; Domenici, C.; Ahluwalia, A. A novel dual-flow bioreactor simulates increased fluorescein permeability in epithelial tissue barriers. Biotechnol. J. 2014, 9, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Choi, Y.Y.; Mo, S.J.; Jeon, S.; Ha, J.H.; Park, S.D.; Shim, J.-J.; Lee, J.; Chung, B.G. Effect of gut microbiota-derived metabolites and extracellular vesicles on neurodegenerative disease in a gut-brain axis chip. Nano Converg. 2024, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, T.D.; Haidacher, S.J.; Engevik, M.A.; Luck, B.; Ruan, W.; Ihekweazu, F.; Bajaj, M.; Hoch, K.M.; Oezguen, N.; Spinler, J.K.; et al. Interrogation of the mammalian gut–brain axis using LC–MS/MS-based targeted metabolomics with in vitro bacterial and organoid cultures and in vivo gnotobiotic mouse models. Nat. Protoc. 2023, 18, 490–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, M.T.; Albani, D.; Giordano, C. An Organ-On-A-Chip Engineered Platform to Study the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis in Neurodegeneration. Trends Mol. Med. 2019, 25, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, V.; Bendtsen, K.M.S. Getting closer to modeling the gut-brain axis using induced pluripotent stem cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1146062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondi, I.; Izzo, L.; Tunesi, M.; Comar, M.; Albani, D.; Giordano, C. Organ-On-A-Chip in vitro Models of the Brain and the Blood-Brain Barrier and Their Value to Study the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Neurodegeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 7, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliari, S.; Tirella, A.; Ahluwalia, A.; Duim, S.; Goumans, M.-J.; Aoyagi, T.; Forte, G. A multistep procedure to prepare pre-vascularized cardiac tissue constructs using adult stem sells, dynamic cell cultures, and porous scaffolds. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, M.; Brandl, B.; Neuhaus, K.; Wudy, S.; Kleigrewe, K.; Hauner, H.; Skurk, T. Effect of dietary fiber on trimethylamine-N-oxide production after beef consumption and on gut microbiota: MEATMARK—A randomized cross-over study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 79, 980–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.S.; Fernandez, M.L. Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO), Diet and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2021, 23, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Gertz, E.R.; Adams, S.H.; Newman, J.W.; Pedersen, T.L.; Keim, N.L.; Bennett, B.J. Effects of a diet based on the Dietary Guidelines on vascular health and TMAO in women with cardiometabolic risk factors. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 32, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.S.; Hazen, S.L.; Tang, W.H.W. Relationship between statin use and trimethylamine N-oxide in cardiovascular risk assessment. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, A115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummen, M.; Solberg, O.G.; Storm-Larsen, C.; Holm, K.; Ragnarsson, A.; Trøseid, M.; Vestad, B.; Skårdal, R.; Yndestad, A.; Ueland, T.; et al. Rosuvastatin alters the genetic composition of the human gut microbiome. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.Y.; Wang, Z.; Jia, X.; Yan, D.; Shih, D.M.; Hazen, S.L.; Lusis, A.J.; Tang, W.H.W. Loop Diuretics Inhibit Renal Excretion of Trimethylamine N-Oxide. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2021, 6, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yi, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ran, L.; Yang, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Mi, M. Resveratrol Attenuates Trimethylamine-N-Oxide (TMAO)-Induced Atherosclerosis by Regulating TMAO Synthesis and Bile Acid Metabolism via Remodeling of the Gut Microbiota. mBio 2016, 7, e02210-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, Q.; Wang, N.; Zhang, L.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y. Quercetin inhibits hepatotoxic effects by reducing trimethylamine-N-oxide formation in C57BL/6J mice fed with a high l-carnitine diet. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, G.; Maisto, M.; Schisano, C.; Ciampaglia, R.; Narciso, V.; Tenore, G.C.; Novellino, E. Effects of Grape Pomace Polyphenolic Extract (Taurisolo®) in Reducing TMAO Serum Levels in Humans: Preliminary Results from a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-Over Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amato, B.; Novellino, E.; Morlando, D.; Vanoli, C.; Vanoli, E.; Ferrara, F.; Difruscolo, R.; Goffredo, V.M.; Compagna, R.; Tenore, G.C.; et al. Benefits of Taurisolo in Diabetic Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study/Year | Population | Setting | Follow-Up | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al., 2017 [39] | N. pts. = 530 | Acute coronary syndrome | 30 day–7 year | TMAO independently predicts MACEs and mortality |

| Li et al., 2022 [55] | Meta-analysis 13,425 pts. | HF | Varied | Higher TMAO predicts MACEs and all-cause mortality |

| Tang et al., 2014 [44] | N. pts. = 720 | Chronic HF | 5 year | High TMAO predicts long-term mortality |

| Suzuki et al., 2016 [43] | N. pts. = 972 | Acute HF | 1 year | TMAO predicts in-hospital and 1 year mortality/HF readmission |

| Zhao et al., 2023 [56] | N. pts. = 1004 | ST-elevation myocardial infarction–percutaneous coronary intervention | 1 year | TMAO predicts MACEs independent of risk factors |

| Therapeutic Area | Intervention/Key Concept | Mechanism or Clinical Relevance | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary Interventions | Diet composition (fiber, animal proteins, dietary patterns) | Diet modulates TMAO production; fiber reduces postprandial TMAO peaks. | Haas et al. 2025 [99] Thomas et al. 2021 [100] Krishnan et al. 2022 [101] |

| Statins | Atorvastatin, Atorvastatin + Ezetimibe, Rosuvastatin | Statins reduce TMAO levels; improved CV risk stratification. | Li DY et al. 2018 [102] Kummen et al. 2020 [103] |

| Loop Diuretics | Furosemide and other loop diuretics | Compete with renal TMAO excretion → increased circulating TMAO → higher CV risk. | Li D.Y. et al. 2021 [104] |

| Nutraceuticals—Resveratrol | Resveratrol | Reduces TMAO; enhances bile acid synthesis; modulates microbiota; activates SIRT pathways. | Chen M et al. 2016 [105] |

| Nutraceuticals—Catechins | Catechin polyphenols | Exert antioxidant and vasoprotective effects. | Chen M et al. 2016 [105] Annunziata et al. [107] Amato et al. 2024 [108] |

| Nutraceuticals—Quercetin | Quercetin | Lowers TMAO; reduces hepatotoxicity; exerts anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. | Zhang et al. 2023 [106] |

| Nutraceuticals—Taurisolo® | Aglianico grape extract | Exert neuroprotective and endothelial-protective effects; reduces TMAO in preclinical studies. | Annunziata et al. [107] Amato et al. 2024 [108] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Calvillo, L.; Vanoli, E.; Ferrara, F.; Caradonna, E. Interplay Among Gut Microbiota-Derived TMAO, Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction, and Heart Failure Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010203

Calvillo L, Vanoli E, Ferrara F, Caradonna E. Interplay Among Gut Microbiota-Derived TMAO, Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction, and Heart Failure Progression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010203

Chicago/Turabian StyleCalvillo, Laura, Emilio Vanoli, Fulvio Ferrara, and Eugenio Caradonna. 2026. "Interplay Among Gut Microbiota-Derived TMAO, Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction, and Heart Failure Progression" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010203

APA StyleCalvillo, L., Vanoli, E., Ferrara, F., & Caradonna, E. (2026). Interplay Among Gut Microbiota-Derived TMAO, Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction, and Heart Failure Progression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010203