A Visual and Rapid PCR Test Strip Method for the Authentication of Sika Deer Meat (Cervus nippon)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

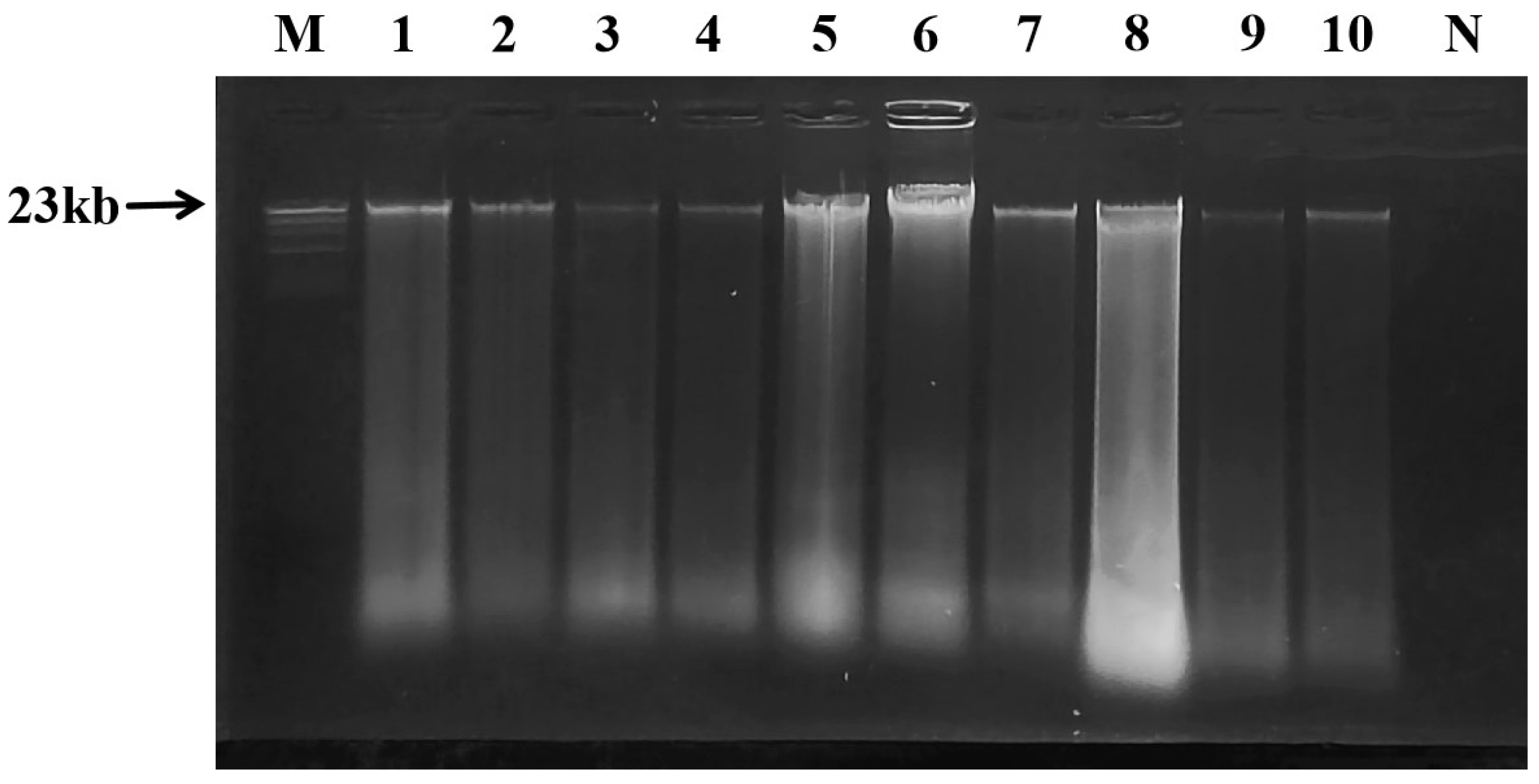

2.1. Genomic DNA Extraction and Quality Verification

2.2. Design and In Silico Analysis of Species-Specific Primers

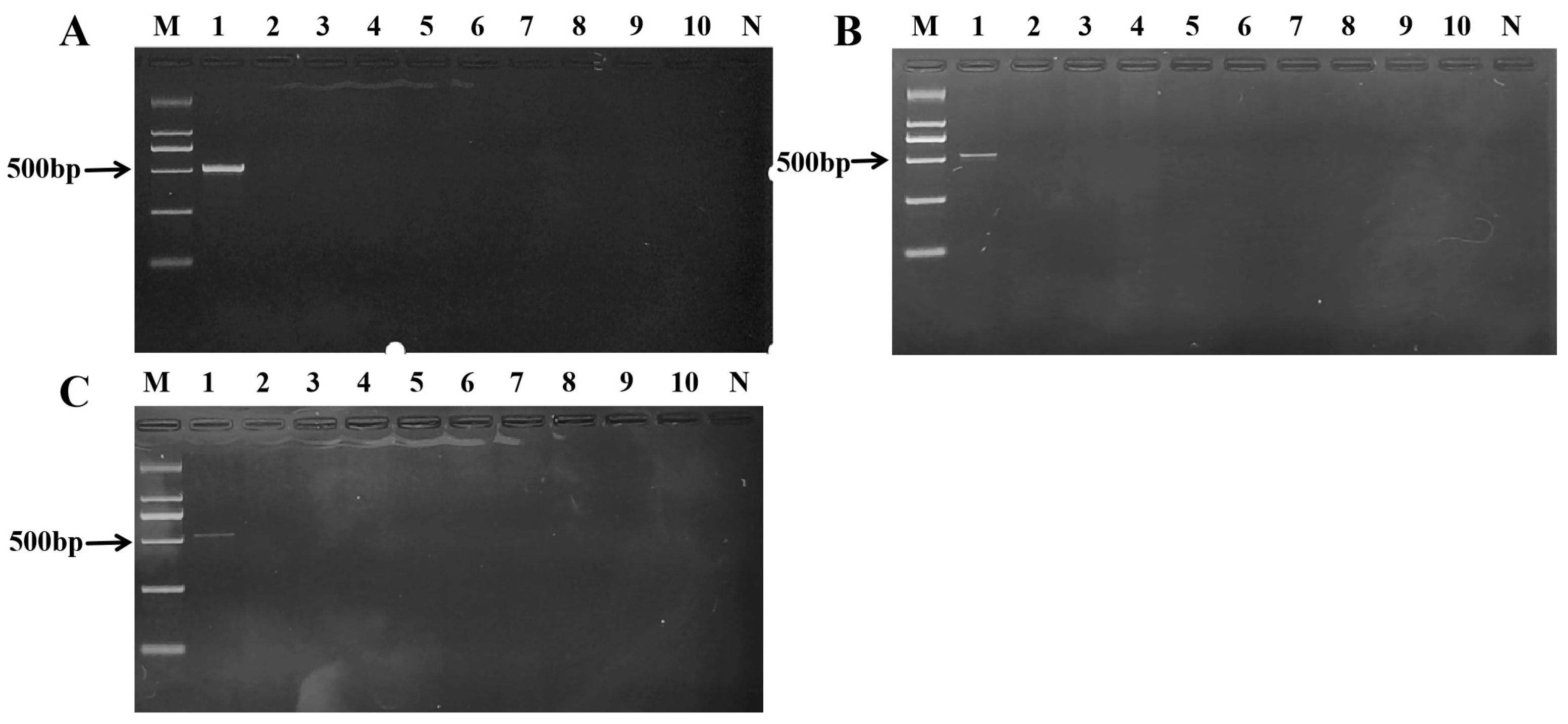

2.3. Determination of Optimal Primer Concentration and Assay Specificity

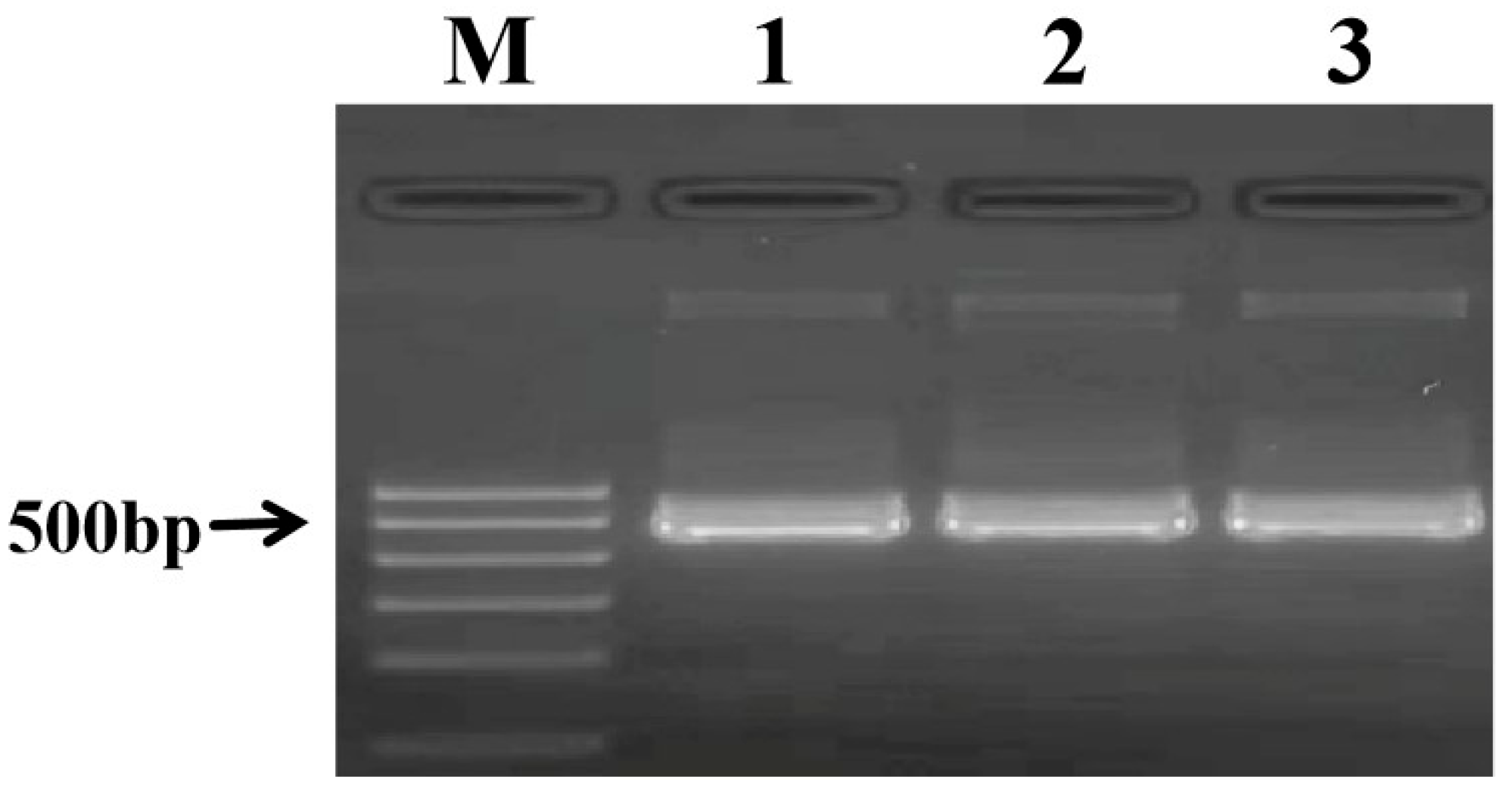

2.4. Construction of a DNA Standard Plasmid for Quality Control

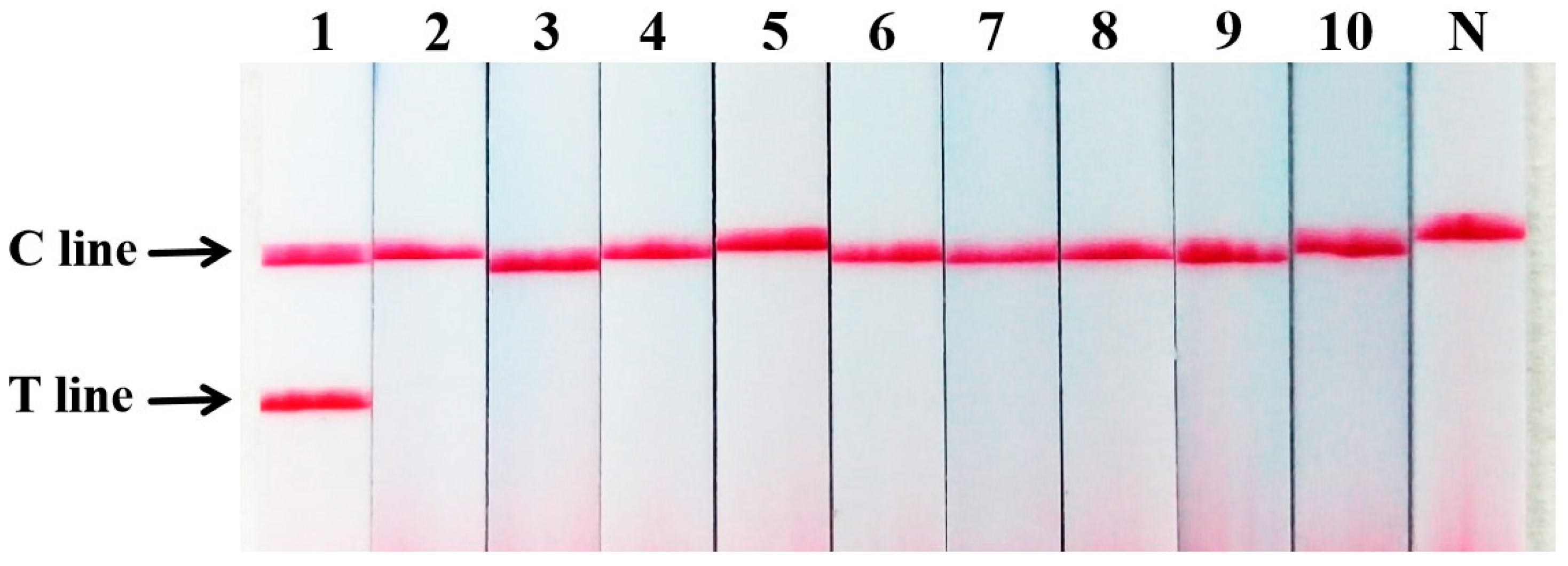

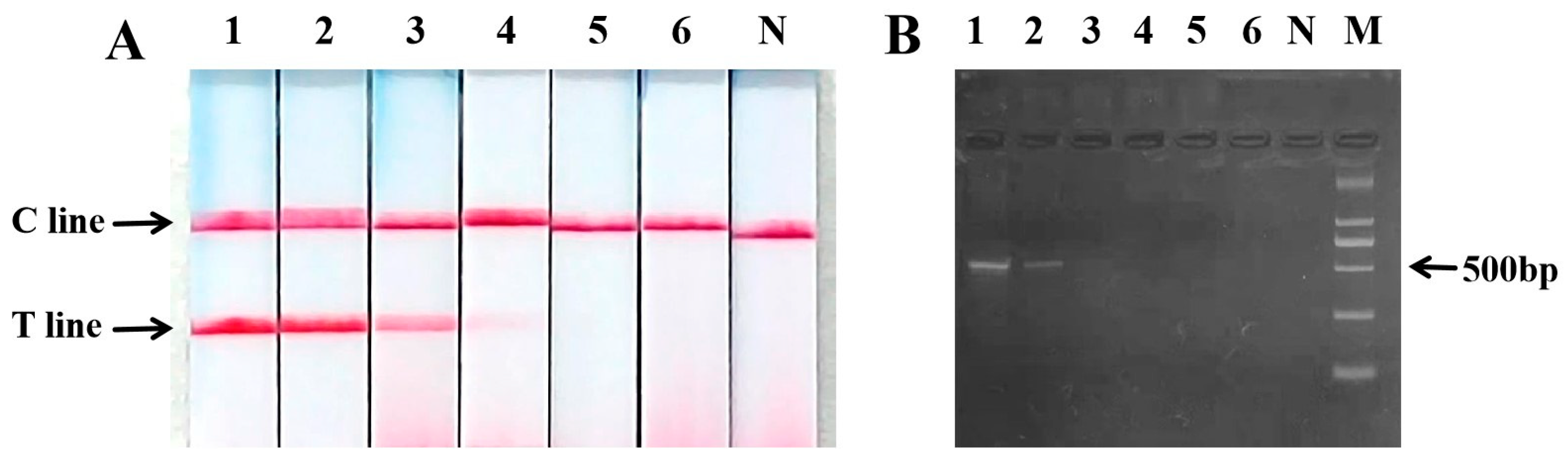

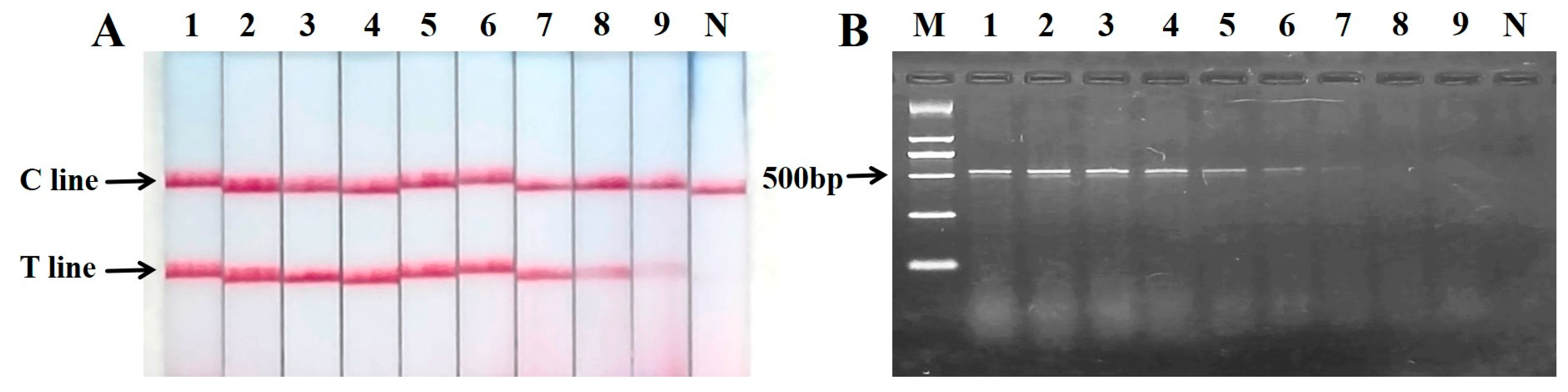

2.5. Sensitivity of PCR Nucleic Acid Test Strip for the Detection of Sika Deer Meat

2.6. Sensitivity of PCR Nucleic Acid Test Strip for the Detection of Mixed Meat Samples

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials, Reagents and Instruments

4.2. Genomic DNA Extraction and Quality Identification of Animal Meats

4.3. Template DNA Amplification and Result Detection

4.3.1. Primer Design

4.3.2. In Silico Specificity Analysis

4.3.3. PCR Amplification and Optimization of Reaction Conditions

4.3.4. PCR Product Detection and Result Interpretation

4.4. Plasmid Construction and Sequencing

4.5. Sensitivity Testing

4.6. Testing of Mixed Meat Samples

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COI | Cytochrome C oxidase subunit I |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PCV2 | Porcine circovirus type 2 |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| Cytc | Cytochrome c |

| Amp | Ampicillin |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry |

References

- An, L.P.; Shi, L.Q.; Ye, Y.J.; Wu, D.K.; Ren, G.K.; Han, X.; Xu, G.Y.; Yuan, G.X.; Du, P.G. Protective effect of Sika Deer bone polypeptide extract on dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in rats. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 52, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Cui, S.; Lu, Y.; Li, Z.; Huo, X.; Wang, Y.; Sha, J.; Sun, Y. Nutritional Processing Quality of Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) Venison in Different Muscles. Foods 2024, 13, 3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, K.; Yang, Y.; Zong, Y.; He, Z.; Chen, W.; Li, J.; Du, R. Effects of sika deer antler protein on immune regulation and intestinal microbiota in mice. J. Funct. Foods 2025, 124, 106637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Q.; Li, Y.D.; Yang, Y.C.; Zhao, S.B.; Shi, H.L.; Yang, C.K.; Wu, M.; Zhang, A.W. Comparison of the composition, immunological activity and anti-fatigue effects of different parts in sika deer antler. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1468237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhao, H.; Luo, J.; Sun, H.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, T. Characteristics of Meat from Farmed Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) and the Effects of Age and Sex on Meat Quality. Foods 2024, 13, 3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, T.; Jang, G.-S.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.; Lim, S.-J.; Park, Y.-C.; Lee, D.-H. Habitat utilization distribution of sika deer (Cervus nippon). Heliyon 2023, 9, e20793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Si, D.; Sabier, M.; Liu, J.J.; Si, J.P.; Zhang, X.F. Guideline for screening antioxidant against lipid-peroxidation by spectrophotometer. eFood 2023, 4, e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulinowski, L.; Luca, S.V.; Skalicka-Wozniak, K. Liquid-liquid chromatography as a promising technology in the separation of food compounds. eFood 2023, 4, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, A.K.; Shrestha, L.; Pokhrel, B.R.; Joshi, B.; Lamichhane, G.; Vidovic, B.; Koirala, N. LC-MS based metabolite profiling, in-vitro antioxidant and in-vivo antihyperlipidemic activity of Nigella sativa extract. eFood 2023, 4, e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Guan, Y.; Men, L.; Sun, J.; Yuan, G. To establish a new quality assessment method based on the regulation of intestinal microbiota in type 2 diabetes by lignans of Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 348, 119822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.X.; Wei, M.; Zhang, Y.X.; Tao, X.L. Analysis of Volatile Organic Compounds of Different Types of Peppers (Capsicum annuum L.) Using Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography With Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. eFood 2024, 5, e70027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Liu, M.Y.; Wang, S.W.; Kang, C.D.; Zhang, M.Y.; Li, Y.Y. Identification and quantification of fox meat in meat products by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2022, 372, 131336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.C.R.; Folli, G.S.; Santos, L.P.; Barros, I.; Oliveira, B.G.; Borghi, F.T.; dos Santos, F.D.; Filgueiras, P.R.; Romao, W. Quantification of beef, pork, and chicken in ground meat using a portable NIR spectrometer. Vib. Spectrosc. 2020, 111, 103158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.H.; Yue, T.L.; Yuan, Y.H.; Shi, Y.H. Unlabeled fluorescence ELISA using yellow emission carbon dots for the detection of Alicyclobacillus acidoterrestris in apple juice. eFood 2023, 4, e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.M.; Ran, D.; Zeng, L.; Xin, M.G. Immunoassay of cooked wild rat meat by ELISA with a highly specific antibody targeting rat heat-resistant proteins. Food Agric. Immunol. 2020, 31, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, N. Comparison of dietary diversity and niche overlap of sympatric sika deer and roe deer based on DNA barcoding in Northeast China. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2023, 69, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Luo, J.; Xu, W.; Li, C.; Guo, L. A novel triplex real-time PCR method for the simultaneous authentication of meats and antlers from sika deer (Cervus nippon) and red deer (Cervus elaphus). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 121, 105390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Yuan, G.X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.H. Establishment of a multiplex-PCR detection method and development of a detection kit for five animal-derived components in edible meat. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.J.; Du, B.Y.; Ma, Q.H.; Ma, Y.H.; Yu, W.Y.; Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, G.X. Multiplex-PCR method application to identify duck blood and its adulterated varieties. Food Chem. 2024, 444, 138673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.S.; Zhang, L.H.; Ai, J.X. Establishment of deer heart identification method and development of the detection kit based on mitochondrial cytochrome B gene. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 66, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.R.; Yu, X.L. Research hotspots and evolution trends of food safety risk assessment techniques and methods. eFood 2024, 5, e70025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetiz, M.V.; Yagi, S.; Kurt, U.; Koyuncu, I.; Yuksekdag, O.; Caprioli, G.; Acquaticci, L.; Angeloni, S.; Senkardes, I.; Zengin, G. Bridging HPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis and in vitro biological activity assay through molecular docking and network pharmacology: The example of European nettle tree (Celtis australis L.). eFood 2024, 5, e70026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, G.; Sakarya, F.B.; Akdas, A.; Atalar, M.N.; Aydogan, C.; Yurt, B.; Capanoglu, E. Comprehensive LC-MS/MS phenolic profiling of Arum elongatum plant and bioaccessibility of phenolics in their infusions. eFood 2024, 5, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Niu, H.M.; Ma, Y.; Yuan, G.X. Isolation, Purification, Fractionation, and Hepatoprotective Activity of Polygonatum Polysaccharides. Molecules 2024, 29, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.-M.; Cui, L.; Ai, J.-X.; Yuan, G.-X.; Sun, L.-Y.; Gao, L.-J.; Li, M.-C. Establishment of a PCR Method for the Identification of Mink-Derived Components in Common Edible Meats. J. Anal. Test. 2021, 6, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, G.X. Development of a species-specific PCR assay for authentication of Agkistrodon acutus based on mitochondrial cytochrome b gene. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 49, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.T.; Sun, J.Y.; Ai, J.X.; Li, Y.N.; Li, M.C.; Zhang, L.H.; Yuan, G.X. Development of Zaocys dhumnades (Cantor) DNA test kit and its application in quality inspection of commercial products. Biomed. Res.-India 2017, 28, 6295–6299. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.C.; Gao, L.J.; Qu, L.; Sun, J.Y.; Yuan, G.X.; Xia, W.; Niu, J.M.; Fu, G.L.; Zhang, L.H. Characteristics of PCR-SSCP and RAPD-HPCE methods for identifying authentication of Penis et testis cervi in Traditional Chinese Medicine based on cytochrome b gene. Mitochondrial DNA Part A 2016, 27, 2757–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.C.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Y.Q.; Li, Z.T.; Yuan, G.X.; Wang, X.S.; Xia, W.; Chen, J.Y. Identification and characteristics of Testudinis Carapax et Plustrum based on fingerprint profiles of mitochondrial DNA constructed by species-specific PCR and random amplified polymorphic DNA. Mitochondrial DNA Part B-Resour. 2018, 3, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Zhou, T.T.; Yu, W.J.; Ai, J.X.; Wang, X.S.; Gao, L.J.; Yuan, G.X.; Li, M.C. Development and evaluation of a PCR-based assay kit for authentication of Zaocys dhumnades in traditional Chinese medicine. Mitochondrial DNA Part A 2018, 29, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | Concentration (ng·mL−1) | Purity (OD A260/A280) |

|---|---|---|

| Blank | 0.300 | 1.000 |

| Sika deer (Cervus nippon) | 256.673 ± 5.046 | 1.850 ± 0.014 |

| Pork (Sus scrofa domesticus) | 163.820 ± 2.851 | 1.827 ± 0.012 |

| Beef (Bos taurus) | 172.907 ± 5.537 | 1.967 ± 0.025 |

| Donkey (Equus asinus) | 153.246 ± 2.740 | 1.813 ± 0.019 |

| Dog (Canis lupus familiaris) | 218.239 ± 2.671 | 1.803 ± 0.005 |

| Lamb (Ovis aries) | 359.711 ± 7.479 | 1.940 ± 0.036 |

| Chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) | 112.372 ± 1.055 | 1.940 ± 0.022 |

| Duck (Anas platyrhynchos domesticus) | 108.324 ± 8.124 | 1.873 ± 0.009 |

| Rat (Rattus norvegicus) | 127.332 ± 0.902 | 1.833 ± 0.026 |

| Mink (Neovison vison) | 147.929 ± 2.101 | 1.976 ± 0.019 |

| Serial No. | Reagents | Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 × Taq PCR Master Mix | Trace Nucleic Acid UV Analyzer |

| (Nanjing Nuoweizan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) | (Q6000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) | |

| 2 | 100 bp DNA Marker | ETC 811 PCR gene amplification instrument |

| (Shanghai Bioengineering Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) | (Suzhou Dongsheng Xingye Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China) | |

| 3 | DNA/HindIII, DH5α competent cells | DYY-8B Double Stable Electrophoresis Instrument |

| (Beijing Dingguo Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) | (Beijing Liuyi Instrument Factory, Beijing, China) | |

| 4 | Agarose | High-speed refrigerated centrifuge |

| (Agrose, Barcelona, Spain) | (Changsha Xiangyi Centrifuge Instrument Co., Ltd., Changsha, China) | |

| 5 | Agarose gel recovery kit | UV WHITE2020D gel imaging analysis system |

| (Nanjing Nuoweizan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) | (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) | |

| 6 | T-vector ligation kit and plasmid extraction kit | GeneAmp R PCR System2700 applied biosystem |

| (Tiangen Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) | (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) | |

| 7 | Ampicillin (Amp) | |

| 8 | 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-galactoside | |

| (X-Gal) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) | ||

| 9 | Isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactopyranoside, | |

| (IPTG) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) | ||

| 10 | Disposable nucleic acid testing strip | |

| (Hangzhou Yousida Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, L.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, G.; Xia, W. A Visual and Rapid PCR Test Strip Method for the Authentication of Sika Deer Meat (Cervus nippon). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010191

Gao L, Xie Y, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Yuan G, Xia W. A Visual and Rapid PCR Test Strip Method for the Authentication of Sika Deer Meat (Cervus nippon). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010191

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Lijun, Yuxin Xie, Yating Zhang, Yi Yang, Guangxin Yuan, and Wei Xia. 2026. "A Visual and Rapid PCR Test Strip Method for the Authentication of Sika Deer Meat (Cervus nippon)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010191

APA StyleGao, L., Xie, Y., Zhang, Y., Yang, Y., Yuan, G., & Xia, W. (2026). A Visual and Rapid PCR Test Strip Method for the Authentication of Sika Deer Meat (Cervus nippon). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010191