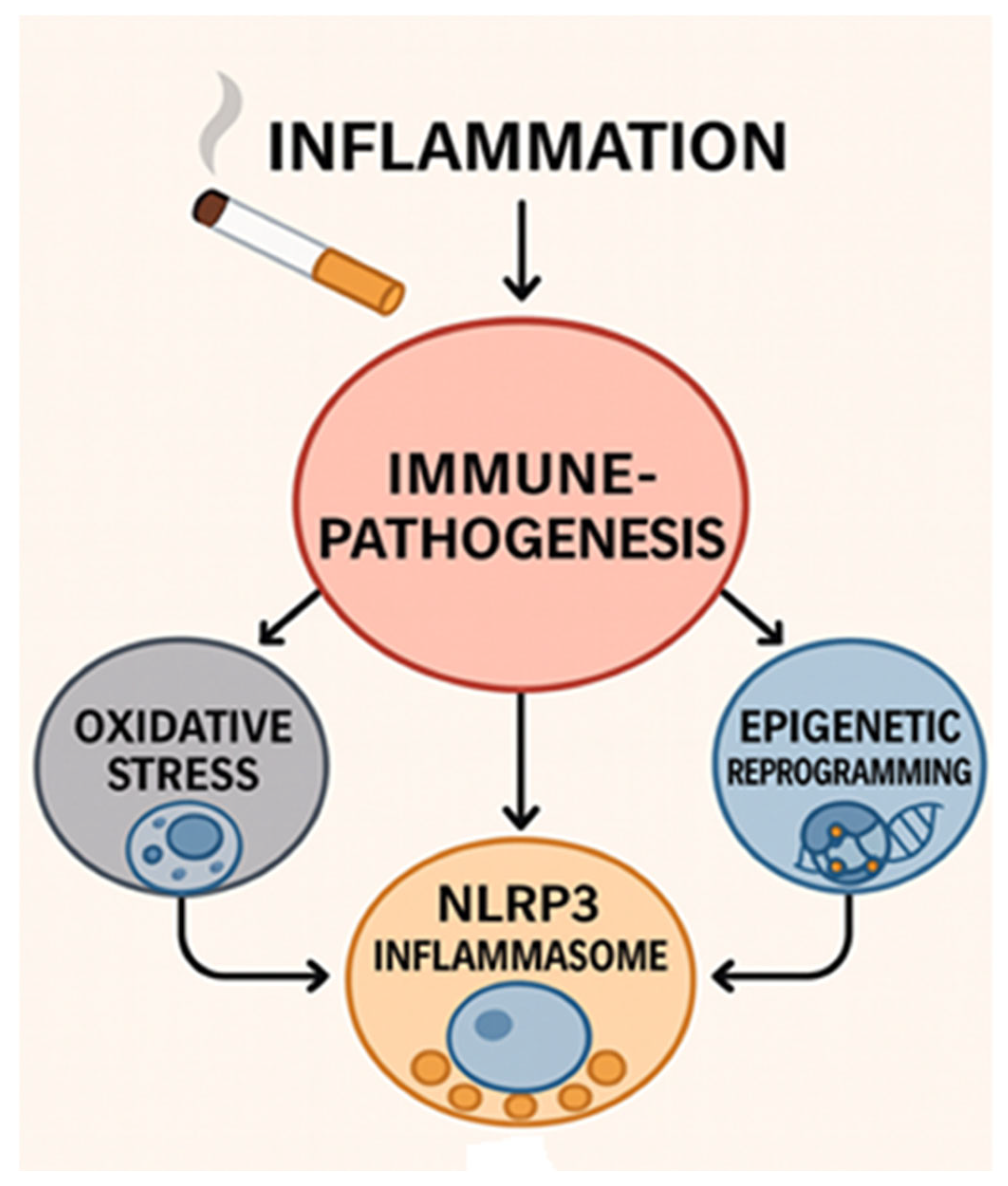

The Convergent Immunopathogenesis of Cigarette Smoke Exposure: From Oxidative Stress to Epigenetic Reprogramming in Chronic Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

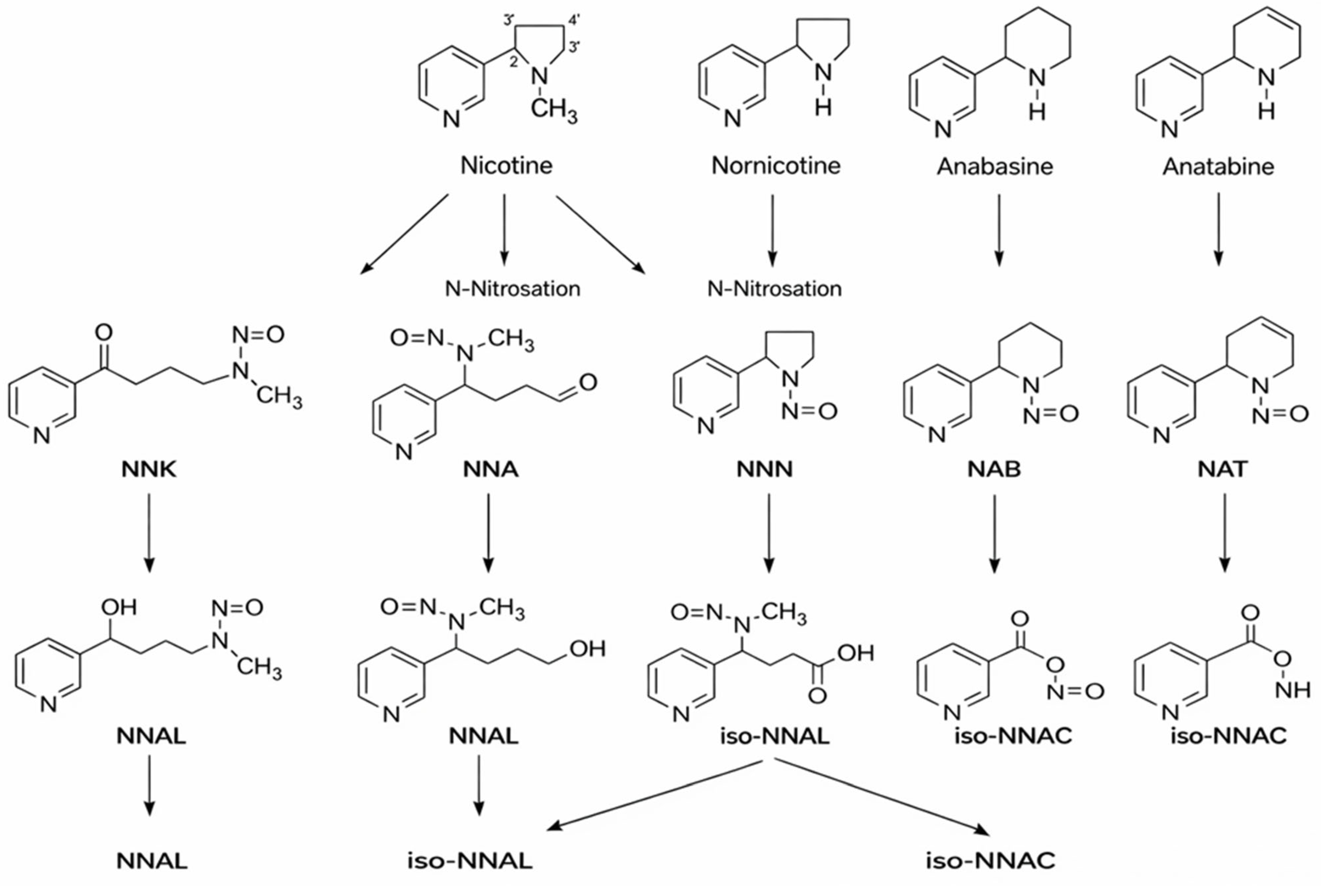

2. Hazardous Compounds in Cigarette Smoke

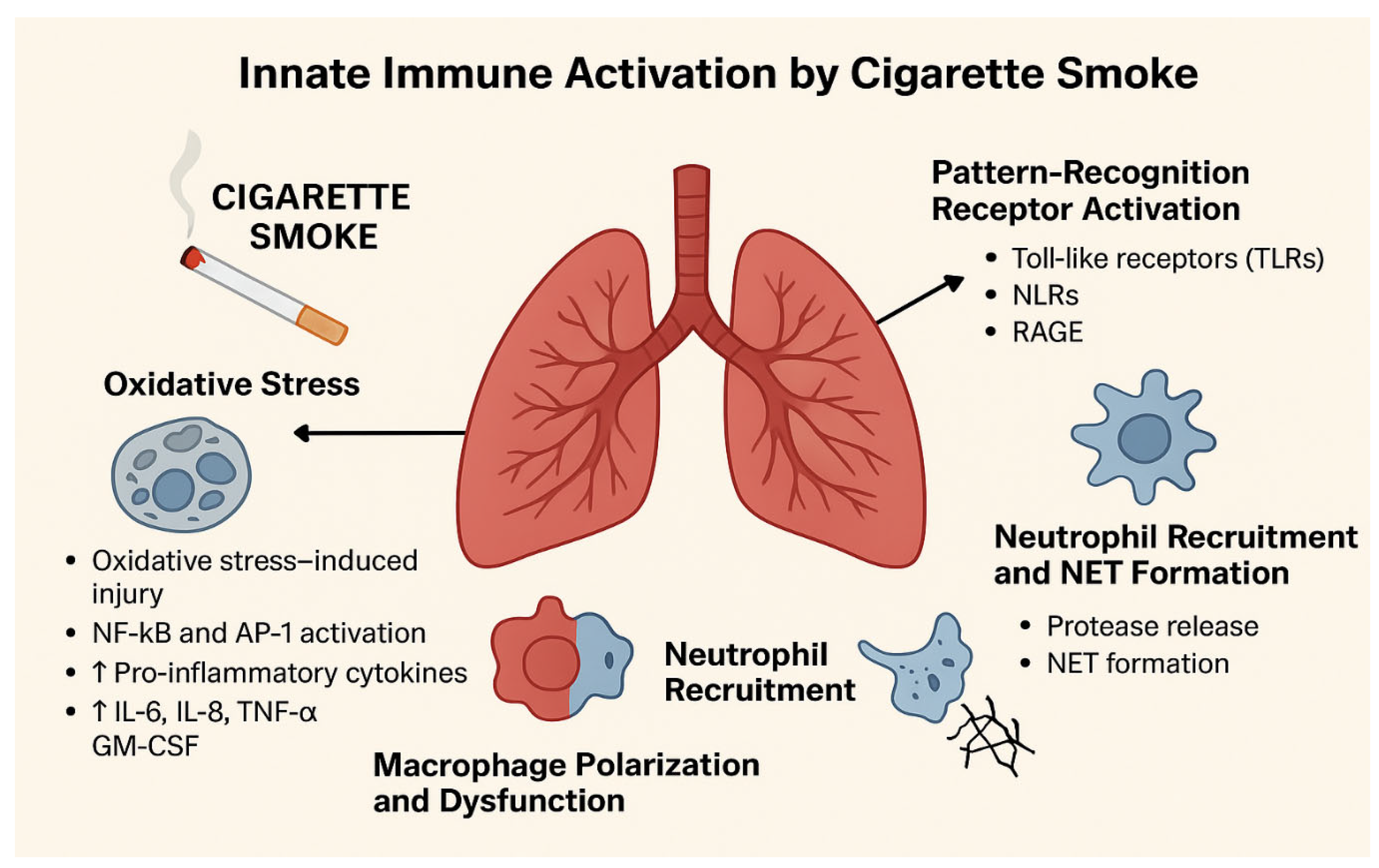

3. Oxidative Stress and Activation of Inflammatory Pathways

4. Innate Immune Dysregulation

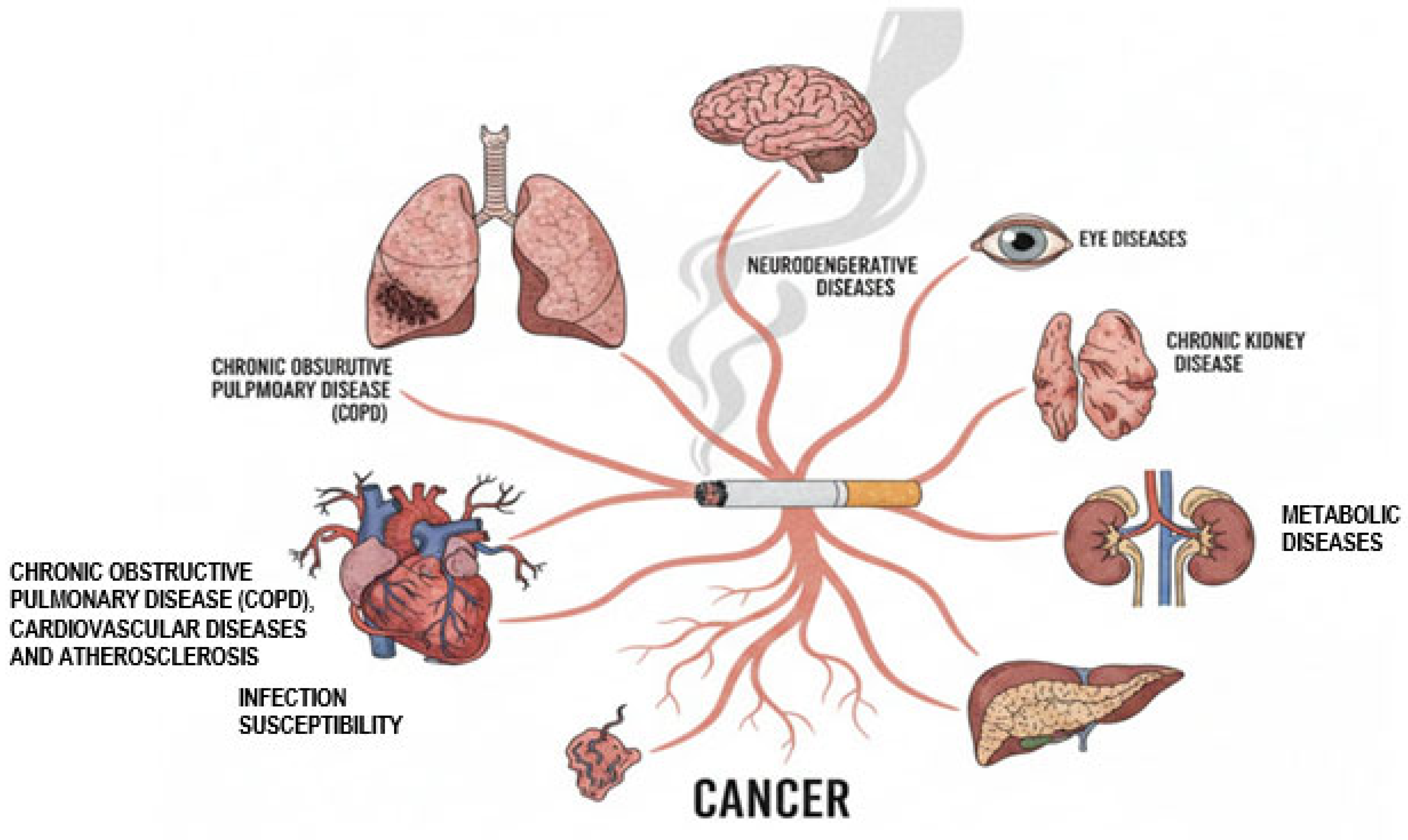

4.1. Airway Epithelial and Alveolar Responses

4.2. Neutrophil Activation

4.3. Impairment of Other Innate Cells

5. Adaptive Immune Responses and Epigenetic Alterations

6. Systemic Immune Dysregulation and Disease Manifestations

6.1. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

6.2. Cardiovascular Diseases and Atherosclerosis

6.3. Infection Susceptibility

6.4. Cancer

6.5. Metabolic Diseases

6.6. Chronic Kidney Disease

6.7. Neurodegenerative Diseases

6.8. Eye Diseases

6.9. Therapeutic Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2021: Addressing New and Emerging Products; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Taneja, V.; Vassallo, R. Cigarette smoking and inflammation: Cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, M.; Sakai, C.; Kobayashi, Y.; Ishida, T. Cigarette Smoking and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2024, 31, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlyarov, S. The Role of Smoking in the Mechanisms of Development of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, F.; Dobaradaran, S.; De-la-Torre, G.E.; Schmidt, T.C.; Saeedi, R. Content of toxic components of cigarette, cigarette smoke vs cigarette butts: A comprehensive systematic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 813, 152667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doz, E.; Noulin, N.; Boichot, E.; Guénon, I.; Fick, L.; Le Bert, M.; Lagente, V.; Ryffel, B.; Schnyder, B.; Quesniaux, V.F.; et al. Cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary inflammation is TLR4/MyD88 and IL-1R1/MyD88 signaling dependent. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US); National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US); Office on Smoking and Health (US). How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General; Publications and Reports of the Surgeon General; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, X.; Chang, C.Y.; You, R.; Shan, M.; Gu, B.H.; Madison, M.C.; Diehl, G.; Perusich, S.; Song, L.Z.; Cornwell, L.; et al. Cigarette smoke-induced reduction of C1q promotes emphysema. JCI Insight 2019, 5, e124317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Q.; Mei, W.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, J. Effects of cigarette smoking on metabolic activity of lung cancer on baseline F-FDG PET/CT. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Ni, X.; Chen, R.; Hou, X. Smoking contribution to the global burden of metabolic disorder: A cluster analysis. Med. Clin. 2024, 163, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, A.; Guo, X.; Li, G.; Zhang, M.; Pu, H. Disease burden of lung cancer attributable to metabolic and behavioral risks in China and globally from 1990 to 2021. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Hou, L.; Lei, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, G. The causal relationship of cigarette smoking to metabolic disease risk and the possible mediating role of gut microbiota. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 290, 117522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.C.; Li, C.I.; Liu, C.S.; Lin, C.H.; Yang, S.Y.; Li, T.C. Relationship between tobacco smoking and metabolic syndrome: A Mendelian randomization analysis. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2025, 25, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhout, R.; Schulz, T.; Florek, E.; van Benthem, J.; Wester, P.; Opperhuizen, A. Hazardous Compounds in Tobacco Smoke. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinou, E.; Fotopoulou, F.; Drosos, A.; Zagoriti, Z.; Niarchos, A.; Makrynioti, D.; Kouretas, D.; Farsalinos, K.; Lagoumintzis, G.; Poulas, K. Tobacco-specific nitrosamines: A literature review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 118, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ortuño, R.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.M.; Fu, M.; Ballbè, M.; Quirós, N.; Fernández, E.; Pascual, J.A. Assessment of tobacco specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) in oral fluid as biomarkers of cancer risk: A population-based study. Environ. Res. 2016, 151, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, L.A.; Stanfill, S.B.; Hecht, S.S. An update on the formation in tobacco, toxicity and carcinogenicity of N’-nitrosonornicotine and 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone. Carcinogenesis 2024, 45, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.; Simonavičius, E.; McNeill, A.; Brose, L.S.; East, K.; Marczylo, T.; Robson, D. Exposure to Tobacco-Specific Nitrosamines Among People Who Vape, Smoke, or do Neither: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2024, 26, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addissouky, T.A.; El Sayed, I.T.E.; Ali, M.M.A.; Wang, Y.; El Baz, A.; Elarabany, N.; Khalil, A.A. Oxidative stress and inflammation: Elucidating mechanisms of smoking-attributable pathology for therapeutic targeting. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2024, 48, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.R.; Jang, J.; Park, S.M.; Ryu, S.M.; Cho, S.J.; Yang, S.R. Cigarette Smoke-Induced Respiratory Response: Insights into Cellular Processes and Biomarkers. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; He, F.; Sergakis, G.G.; Koozehchian, M.S.; Stimpfl, J.N.; Rong, Y.; Diaz, P.T.; Best, T.M. Interrelated role of cigarette smoking, oxidative stress, and immune response in COPD and corresponding treatments. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2014, 307, L205–L218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rom, O.; Avezov, K.; Aizenbud, D.; Reznick, A.Z. Cigarette smoking and inflammation revisited. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2013, 187, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khudhur, Z.O.; Smail, S.W.; Awla, H.K.; Ahmed, G.B.; Khdhir, Y.O.; Amin, K.; Janson, C. The effects of heavy smoking on oxidative stress, inflammatory biomarkers, vascular dysfunction, and hematological indices. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 18251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadkhaniha, R.; Yousefian, F.; Rastkari, N. Impact of smoking on oxidant/antioxidant status and oxidative stress index levels in serum of the university students. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2021, 19, 1043–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.-S.; Park, K.-H.; Park, J.-M.; Jeong, H.; Kim, B.; Jeon, J.S.; Yu, J.; Kim, S.K.; Lee, K.; Lee, M.-Y. Short-term inhalation exposure to cigarette smoke induces oxidative stress and inflammation in lungs without systemic oxidative stress in mice. Toxicol. Res. 2024, 40, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starke, R.M.; Thompson, J.W.; Ali, M.S.; Pascale, C.L.; Martinez Lege, A.; Ding, D.; Chalouhi, N.; Hasan, D.M.; Jabbour, P.; Owens, G.K.; et al. Cigarette Smoke Initiates Oxidative Stress-Induced Cellular Phenotypic Modulation Leading to Cerebral Aneurysm Pathogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijink, I.H.; Brandenburg, S.M.; Postma, D.S.; van Oosterhout, A.J.M. Cigarette smoke impairs airway epithelial barrier function and cell–cell contact recovery. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 39, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghapour, M.; Raee, P.; Moghaddam, S.J.; Hiemstra, P.S.; Heijink, I.H. Airway Epithelial Barrier Dysfunction in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Role of Cigarette Smoke Exposure. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2017, 58, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spira, A.; Beane, J.; Shah, V.; Liu, G.; Schembri, F.; Yang, X.; Palma, J.; Brody, J.S. Effects of cigarette smoke on the human airway epithelial cell transcriptome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 10143–10148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballweg, K.; Mutze, K.; Königshoff, M.; Eickelberg, O.; Meiners, S. Cigarette smoke extract affects mitochondrial function in alveolar epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2014, 307, L895–L907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoshiba, K.; Nagai, A. Oxidative stress, cell death, and other damage to alveolar epithelial cells induced by cigarette smoke. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2003, 1, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussell, T.; Bell, T.J. Alveolar macrophages: Plasticity in a tissue-specific context. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugg, S.T.; Scott, A.; Parekh, D.; Naidu, B.; Thickett, D.R. Cigarette smoke exposure and alveolar macrophages: Mechanisms for lung disease. Thorax 2022, 77, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilliams, M.; De Kleer, I.; Henri, S.; Post, S.; Vanhoutte, L.; De Prijck, S.; Deswarte, K.; Malissen, B.; Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.N. Alveolar macrophages develop from fetal monocytes that differentiate into long-lived cells in the first week of life via GM-CSF. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 1977–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisia, I.; Lam, V.; Cho, B.; Hay, M.; Li, M.Y.; Yeung, M.; Bu, L.; Jia, W.; Norton, N.; Lam, S.; et al. The effect of smoking on chronic inflammation, immune function and blood cell composition. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Chen, Q.; Xie, M. Smoking increases the risk of infectious diseases: A narrative review. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2020, 18, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, M.; Kakemizu, N.; Ito, T.; Kudo, M.; Kaneko, T.; Suzuki, M.; Udaka, N.; Ikeda, H.; Okubo, T. Superoxide mediates cigarette smoke-induced infiltration of neutrophils into the airways through nuclear factor-kappaB activation and IL-8 mRNA expression in guinea pigs in vivo. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1999, 20, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahdah, A.; Jaggers, R.M.; Sreejit, G.; Johnson, J.; Kanuri, B.; Murphy, A.J.; Nagareddy, P.R. Immunological Insights into Cigarette Smoking-Induced Cardiovascular Disease Risk. Cells 2022, 11, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stämpfli, M.R.; Anderson, G.P. How cigarette smoke skews immune responses to promote infection, lung disease and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, O.J.; Foley, J.; Bolognese, B.J.; Long, E., 3rd; Podolin, P.L.; Walsh, P.T. Airway infiltration of CD4+ CCR6+ Th17 type cells associated with chronic cigarette smoke induced airspace enlargement. Immunol. Lett. 2008, 121, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavitz, C.C.; Gaschler, G.J.; Robbins, C.S.; Botelho, F.M.; Cox, P.G.; Stampfli, M.R. Impact of cigarette smoke on T and B cell responsiveness. Cell. Immunol. 2008, 253, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, L.; Yang, H.; Wu, X.; Luo, X.; Shen, J.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Du, F.; Chen, Y.; et al. Dysregulation of immunity by cigarette smoking promotes inflammation and cancer: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 339, 122730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-André, V.; Charbit, B.; Biton, A.; Rouilly, V.; Possémé, C.; Bertrand, A.; Rotival, M.; Bergstedt, J.; Patin, E.; Albert, M.L.; et al. Smoking changes adaptive immunity with persistent effects. Nature 2024, 626, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, B.; Chen, Q.; Dai, Z.; Jiang, C.; Chen, X. Progesterone (P4) ameliorates cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Guan, S.; Ge, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, J. Cigarette smoke promotes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) through the miR-130a/Wnt1 axis. Toxicol. Vitr. 2020, 65, 104770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvi, S. Tobacco smoking and environmental risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin. Chest Med. 2014, 35, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, G.B. Guiding policy to reduce the burden of COPD: The role of epidemiological research. Thorax 2018, 73, 405–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schayck, O.C.P.; Williams, S.; Barchilon, V.; Baxter, N.; Jawad, M.; Katsaounou, P.A.; Kirenga, B.J.; Panaitescu, C.; Tsiligianni, I.G.; Zwar, N.; et al. Treating tobacco dependence: Guidance for primary care on life-saving interventions. Position statement of the IPCRG. NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2017, 27, 38, Erratum in NPJ Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2017, 27, 52. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-017-0048-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamprecht, B.; Soriano, J.B.; Studnicka, M.; Kaiser, B.; Vanfleteren, L.E.; Gnatiuc, L.; Burney, P.; Miravitlles, M.; García-Rio, F.; Akbari, K.; et al. BOLD Collaborative Research Group, the EPI-SCAN Team, the PLATINO Team, and the PREPOCOL Study Group. Determinants of underdiagnosis of COPD in national and international surveys. Chest 2015, 148, 971–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troosters, T.; Blondeel, A.; Janssens, W.; Demeyer, H. The past, present and future of pulmonary rehabilitation. Respirology 2019, 24, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauler, M.; McDonough, J.E.; Adams, T.S.; Kothapalli, N.; Barnthaler, T.; Werder, R.B.; Schupp, J.C.; Nouws, J.; Robertson, M.J.; Coarfa, C.; et al. Characterization of the COPD alveolar niche using single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Cai, W.; Tang, H.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhou, D.; Wang, R.; Ye, M.; et al. A unified single-cell atlas of human lung provides insights into pulmonary diseases. eBioMedicine 2025, 122, 106025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelgrim, C.E.; Peterson, J.D.; Gosker, H.R.; Schols, A.M.W.J.; van Helvoort, A.; Garssen, J.; Folkerts, G.; Kraneveld, A.D. Psychological co-morbidities in COPD: Targeting systemic inflammation, a benefit for both? Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 842, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messner, B.; Bernhard, D. Smoking and cardiovascular disease: Mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction and early atherogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2014, 34, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kjerulff, B.; Kaspersen, K.A.; Dinh, K.M.; Boldsen, J.; Mikkelsen, S.; Erikstrup, L.T.; Sørensen, E.; Nielsen, K.R.; Bruun, M.T.; Hjalgrim, H.; et al. Smoking is associated with infection risk in healthy blood donors. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 29, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.F.; Danchuk, S.; Wang, Y.; Xu, B.; Rando, R.J.; Brody, A.R.; Shan, B.; Sullivan, D.E. Cigarette smoke represses the innate immune response to asbestos. Physiol. Rep. 2015, 3, e12652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, T.; Hirata, T.; Ishikawa, S.; Ito, S.; Ishimori, K.; Matsumura, K.; Muraki, K. Regulation of NRF2, AP-1 and NF-κB by cigarette smoke exposure in three-dimensional human bronchial epithelial cells. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2019, 39, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Li, J.; Song, Q.; Cheng, W.; Chen, P. The role of HMGB1/RAGE/TLR4 signaling pathways in cigarette smoke-induced inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2022, 10, e711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Wu, S.; Huang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Yu, H.; Bai, X.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Z.; Li, L.; Mei, Y.; et al. Smoking promotes the progression of bladder cancer through FOXM1/CKAP2L axis. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Park, H.S.; Chiang, A.C. Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Review. JAMA 2025, 333, 1906–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Li, G.; Xu, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, T.; Han, T.; Sun, C.; Ma, J.; et al. Impact of maternal and offspring smoking and breastfeeding on oesophageal cancer in adult offspring. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.; Lee, G.; Kim, S.; Chen, Q.Y.; Park, Y.; Keum, N. Meta-analysis of smoking and breast cancer risk: By age of smoking initiation. Breast Cancer 2025, 32, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.Y.; Liu, K.; Wallar, G.; Zhou, J.Y.; Mu, L.N.; Liu, X.; Li, L.M.; He, N.; Wu, M.; Zhao, J.K.; et al. Environmental tobacco smoking (ETS) and esophageal cancer: A population-based case-control study in Jiangsu Province, China. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 156, 1552–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, L.; Xu, R.; Ren, Y.; Meng, C.; Wang, P.; Wu, Q.; Song, L.; Du, Z. Smoking exposure and cervical cancer risk: Integrating observational and genetic evidence. J. Int. Med. Res. 2025, 53, 3000605251383687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Gao, X.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Hu, B.; Gao, Q.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; et al. Plasma Metabolomic Signatures of H. pylori Infection, Alcohol Drinking, Smoking, and Risk of Gastric Cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 2025, 64, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, P. Cancer, cigarette smoking and premature death in Europe: A review including the Recommendations of European Cancer Experts Consensus Meeting, Helsinki, October 1996. Lung Cancer 1997, 17, 1–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwar, N.; Gao, P.; Seshasai, S.R.; Gobin, R.; Kaptoge, S.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Ingelsson, E.; Lawlor, D.A.; Selvin, E.; Stampfer, M.; et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: A collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet 2010, 375, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease—A global public health perspective. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Repositioning of the global epicentre of non-optimal cholesterol. Nature 2020, 582, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okunogbe, A.; Nugent, R.; Spencer, G.; Powis, J.; Ralston, J.; Wilding, J. Economic impacts of overweight and obesity: Current and future estimates for 161 countries. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e009773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, N.W.S.; Ng, C.H.; Tan, D.J.H.; Kong, G.; Lin, C.; Chin, Y.H.; Lim, W.H.; Huang, D.Q.; Quek, J.; Fu, C.E.; et al. The global burden of metabolic disease: Data from 2000 to 2019. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 414–428.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.H.; Jung, Y.S.; Hong, H.P.; Park, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Park, D.I.; Cho, Y.K.; Sohn, C.I.; Jeon, W.K.; Kim, B.I. Association between cotinine-verified smoking status and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Liver Int. 2018, 38, 1487–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddatu, J.; Anderson-Baucum, E.; Evans-Molina, C. Smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes. Transl. Res. 2017, 184, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, C.; Li, J.; Guo, X.; Lv, Y.; Yu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Jin, L. The associations between smoking and obesity in northeast China: A quantile regression analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titova, O.E.; Baron, J.A.; Fall, T.; Michaëlsson, K.; Larsson, S.C. Swedish Snuff (Snus), Cigarette Smoking, and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2023, 65, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Bidulescu, A. The association between e-cigarette use or dual use of e-cigarette and combustible cigarette and prediabetes, diabetes, or insulin resistance: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2023, 251, 110948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reaven, G.; Tsao, P.S. Insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia: The key player between cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 1044–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Zhou, Z.; Yun, H.; Park, S.; Choi, S.J.; Lee, S.H.; Lim, C.W.; Lee, K.; Kim, B. Cigarette smoking differentially regulates inflammatory responses in a mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis depending on exposure time point. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 135, 110930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.; Kolci, K.; Bahcivan, İ.; Coskun, G.P.; Sipahi, H. Alpha-Lipoic Acid Modulates the Oxidative and Inflammatory Responses Induced by Traditional and Novel Tobacco Products in Human Liver Epithelial Cells. Chem. Biodivers. 2023, 20, e202200928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Chaudhry, Z.; Lee, C.C.; Bone, R.N.; Kanojia, S.; Maddatu, J.; Sohn, P.; Weaver, S.A.; Robertson, M.A.; Petrache, I.; et al. Cigarette smoke exposure impairs β-cell function through activation of oxidative stress and ceramide accumulation. Mol. Metab. 2020, 37, 100975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlach, V.; Vergès, B.; Al-Salameh, A.; Bahougne, T.; Benzerouk, F.; Berlin, I.; Clair, C.; Mansourati, J.; Rouland, A.; Thomas, D.; et al. Smoking and diabetes interplay: A comprehensive review and joint statement. Diabetes Metab. 2022, 48, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözmen, K.; Unal, B.; Capewell, S.; Critchley, J.; O’Flaherty, M. Estimating diabetes prevalence in Turkey in 2025 with and without possible interventions to reduce obesity and smoking prevalence, using a modelling approach. Int. J. Public Health 2015, 60 (Suppl. S1), S13–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, C.; Anderson, R. Smoking, Alcohol Use, Diabetes Mellitus, and Metabolic Syndrome as Risk Factors for Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Clin. Chest Med. 2025, 46, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambaro, G.; Verlato, F.; Budakovic, A.; Casara, D.; Saladini, G.; Del Prete, D.; Bertaglia, G.; Masiero, M.; Checchetto, S.; Baggio, B. Renal impairment in chronic cigarette smokers. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1998, 9, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, H.T.; Xu, Q.Q.; Zhuo, L.; Li, W.G. Smoking as a causative factor in chronic kidney disease: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Ren. Fail. 2025, 47, 2453014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orth, S.R.; Schroeder, T.; Ritz, E.; Ferrari, P. Effects of smoking on renal function in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2005, 20, 2414–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hovind, P.; Rossing, P.; Tarnow, L.; Parving, H.H. Smoking and progression of diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Sietsma, S.J.; Mulder, J.; Janssen, W.M.; Hillege, H.L.; de Zeeuw, D.; de Jong, P.E. Smoking is related to albuminuria and abnormal renal function in nondiabetic persons. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000, 133, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Chronic diseases and aging. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayyas, F.; Alzoubi, K.H. Impact of cigarette smoking on kidney inflammation and fibrosis in diabetic rats. Inhal. Toxicol. 2019, 31, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albillos, A.; McIntosh, J.M. Human nicotinic receptors in chromaffin cells: Characterization and pharmacology. Pflug. Arch. 2018, 470, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cora, N.; Ghandour, J.; Pollard, C.M.; Desimine, V.L.; Ferraino, K.E.; Pereyra, J.M.; Valiente, R.; Lymperopoulos, A. Nicotine-induced adrenal beta-arrestin1 upregulation mediates tobacco-related hyperaldosteronism leading to cardiac dysfunction. World J. Cardiol. 2020, 12, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejerblad, E.; Fored, C.M.; Lindblad, P.; Fryzek, J.; Dickman, P.W.; Elinder, C.G.; McLaughlin, J.K.; Nyrén, O. Association between smoking and chronic renal failure in a nationwide population-based case-control study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 2178–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnello, L.; Gambino, C.M.; Lo Sasso, B.; Bivona, G.; Milano, S.; Ciaccio, A.M.; Piccoli, T.; La Bella, V.; Ciaccio, M. Neurogranin as a Novel Biomarker in Alzheimer’s Disease. Lab. Med. 2021, 52, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Hecht, S.S. Carcinogenic components of tobacco and tobacco smoke: A 2022 update. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 165, 113179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zhu, S.; Zheng, Z.; Ding, X.; Shi, W.; Xia, T.; Gu, X. A Genome-wide study on the genetic and causal effects of smoking in neurodegeneration. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, T.; Arnds, J.; Mohr, S.; Schreiner, L.; Helbig, H. Rauchen und Augenerkrankungen [Smoking and eye diseases]. Die Ophthalmol. 2025, 122, 753–762. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, T.; Yang, L.; Qian, W.; Fang, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Yu, B.; Sun, J.; et al. Cigarette Smoking Drives Thyroid Eye Disease Progression via RAGE Signaling Activation. Thyroid 2025, 35, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Dong, X.; Yang, T.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; He, J.; Wu, M.; Wei-Zhang, S.; Kaysar, P.; Cui, B.; et al. Smoking aggravates neovascular age-related macular degeneration via Sema4D-PlexinB1 axis-mediated activation of pericytes. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, J.; Shi, L.; Huang, J. Causal associations between smoking and ocular diseases: A Mendelian randomization study. Adv. Ophthalmol. Pract. Res. 2025, 5, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiamah, R.; Ampo, E.; Ampiah, E.E.; Nketia, M.O.; Kyei, S. Impact of smoking on ocular health: A systematic review and meta-meta-analysis. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 35, 1506–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.P.; Rabe, K.F.; Hanania, N.A.; Vogelmeier, C.F.; Cole, J.; Bafadhel, M.; Christenson, S.A.; Papi, A.; Singh, D.; Laws, E.; et al. Dupilumab for COPD with Type 2 Inflammation Indicated by Eosinophil Counts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.P.; Rabe, K.F.; Hanania, N.A.; Vogelmeier, C.F.; Bafadhel, M.; Christenson, S.A.; Papi, A.; Singh, D.; Laws, E.; Patel, N.; et al. Dupilumab for COPD with Blood Eosinophil Evidence of Type 2 Inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 390, 2274–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzueto, A.; Barjaktarevic, I.Z.; Siler, T.M.; Rheault, T.; Bengtsson, T.; Rickard, K.; Sciurba, F. Ensifentrine, a Novel Phosphodiesterase 3 and 4 Inhibitor for the Treatment of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-controlled, Multicenter Phase III Trials (the ENHANCE Trials). Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 208, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otake, S.; Chubachi, S.; Miyamoto, J.; Haneishi, Y.; Arai, T.; Iizuka, H.; Shimada, T.; Sakurai, K.; Okuzumi, S.; Kabata, H.; et al. Impact of smoking on gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids in human and mice: Implications for COPD. Mucosal Immunol. 2025, 18, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiman, V.; Chuang, H.C.; Lo, Y.C.; Yuan, T.H.; Chen, Y.Y.; Heriyanto, D.S.; Yuliani, F.S.; Chung, K.F.; Chang, J.H. Cigarette smoke-induced dysbiosis: Comparative analysis of lung and intestinal microbiomes in COPD mice and patients. Respir. Res. 2024, 25, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

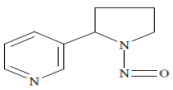

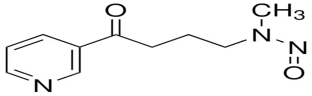

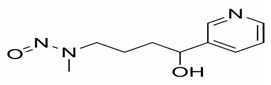

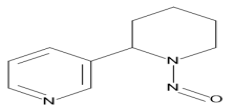

| TSNAs | Structure | Effects |

|---|---|---|

| N′-nitrosonornicotine (NNN) |  | Esophageal cancer, Nasal and oral cavity cancer |

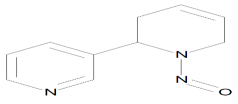

| 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK) |  | Lung cancer, Pancreas cancer, Liver cancer, Nasal and oral cavity cancer |

| 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol (NNAL) |  | Lung cancer, Pancreas cancer, Liver cancer, Nasal and oral cavity cancer |

| N′-nitrosoanabasine (NAB) |  | Esophageal cancer, Nasal cavity cancer |

| N′-nitrosoanatabine (NAT) |  | Esophageal cancer, Nasal cavity cancer |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fenercioglu, A.K.; Uzun, H.; Unal, D.O. The Convergent Immunopathogenesis of Cigarette Smoke Exposure: From Oxidative Stress to Epigenetic Reprogramming in Chronic Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010187

Fenercioglu AK, Uzun H, Unal DO. The Convergent Immunopathogenesis of Cigarette Smoke Exposure: From Oxidative Stress to Epigenetic Reprogramming in Chronic Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010187

Chicago/Turabian StyleFenercioglu, Aysen Kutan, Hafize Uzun, and Durisehvar Ozer Unal. 2026. "The Convergent Immunopathogenesis of Cigarette Smoke Exposure: From Oxidative Stress to Epigenetic Reprogramming in Chronic Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010187

APA StyleFenercioglu, A. K., Uzun, H., & Unal, D. O. (2026). The Convergent Immunopathogenesis of Cigarette Smoke Exposure: From Oxidative Stress to Epigenetic Reprogramming in Chronic Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010187