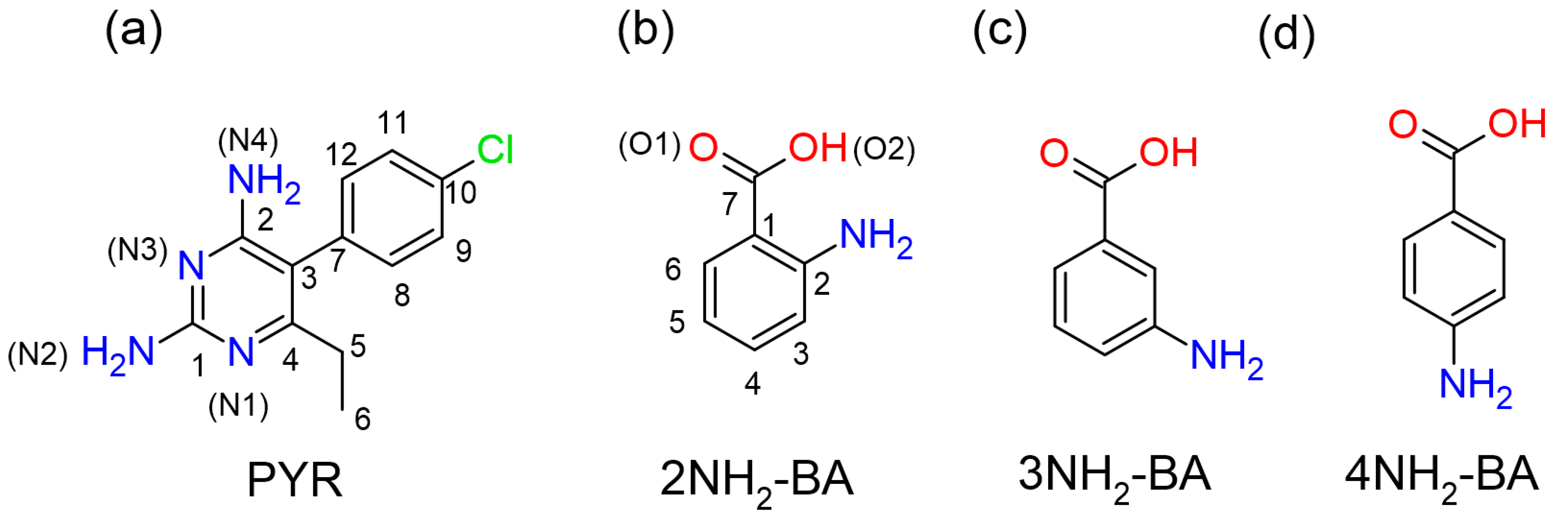

Salts of Antifolate Pyrimethamine with Isomeric Aminobenzoic Acids: Exploring Packing Interactions and Pre-Crystallization Aggregation

Abstract

1. Introduction

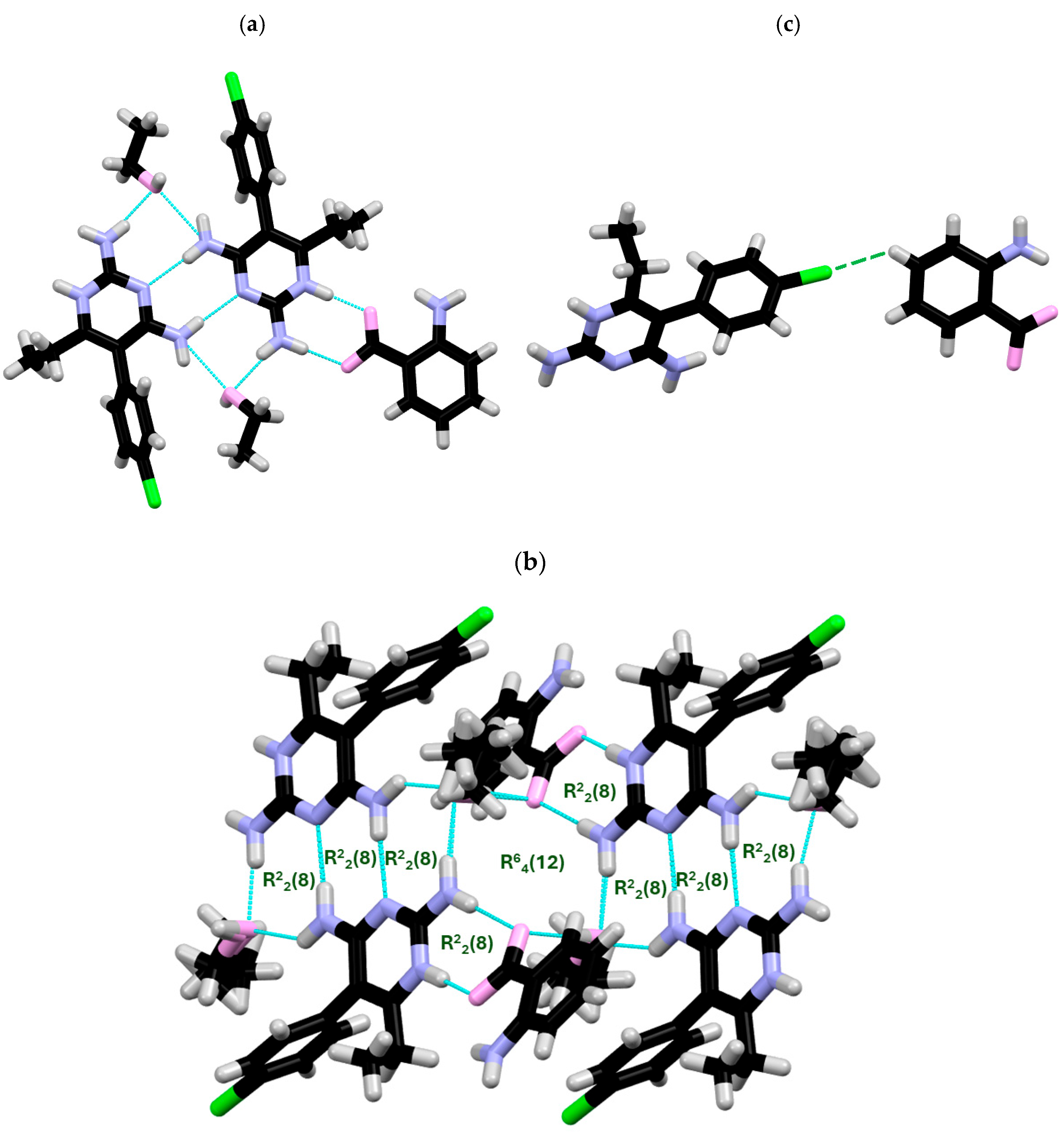

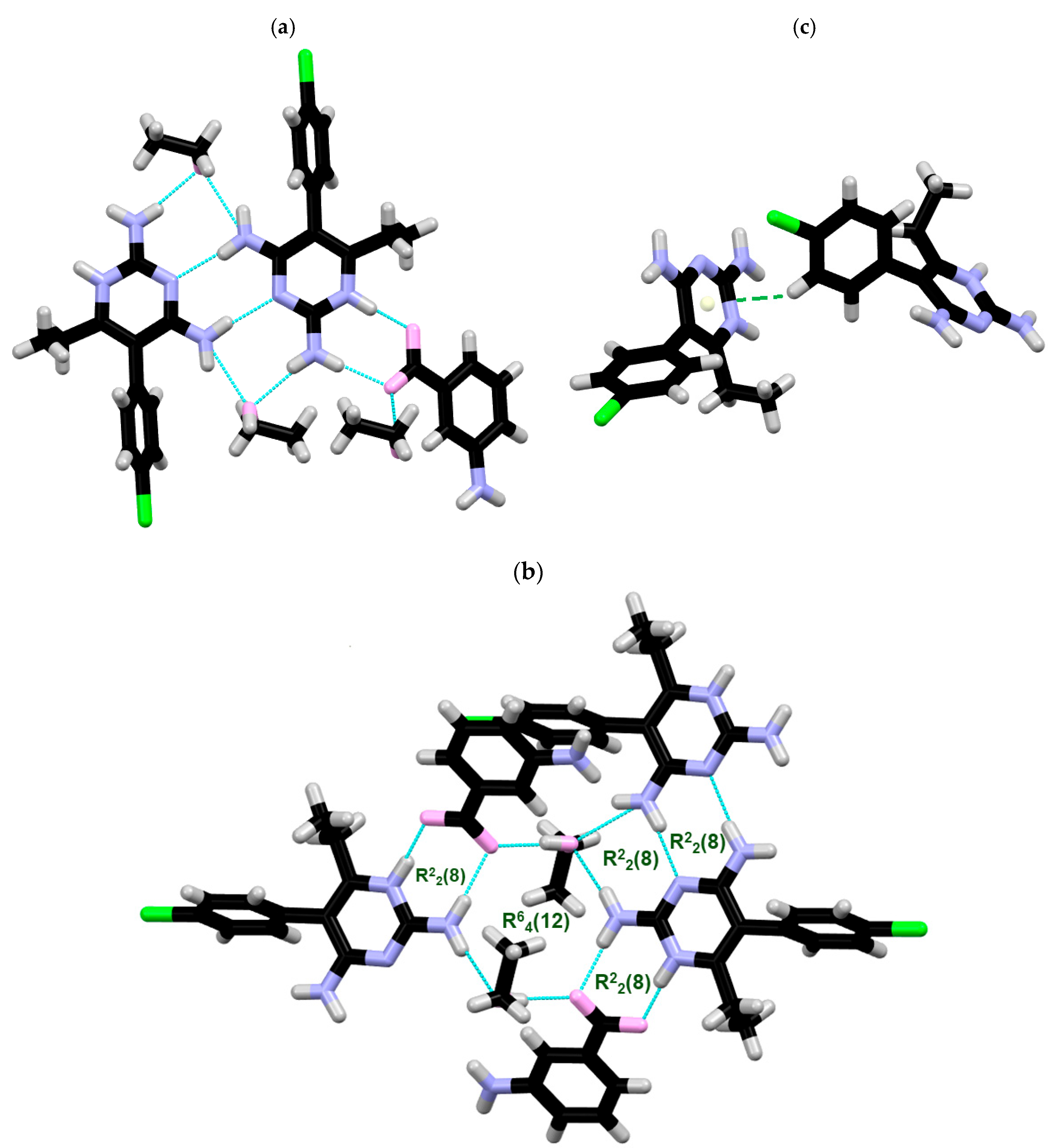

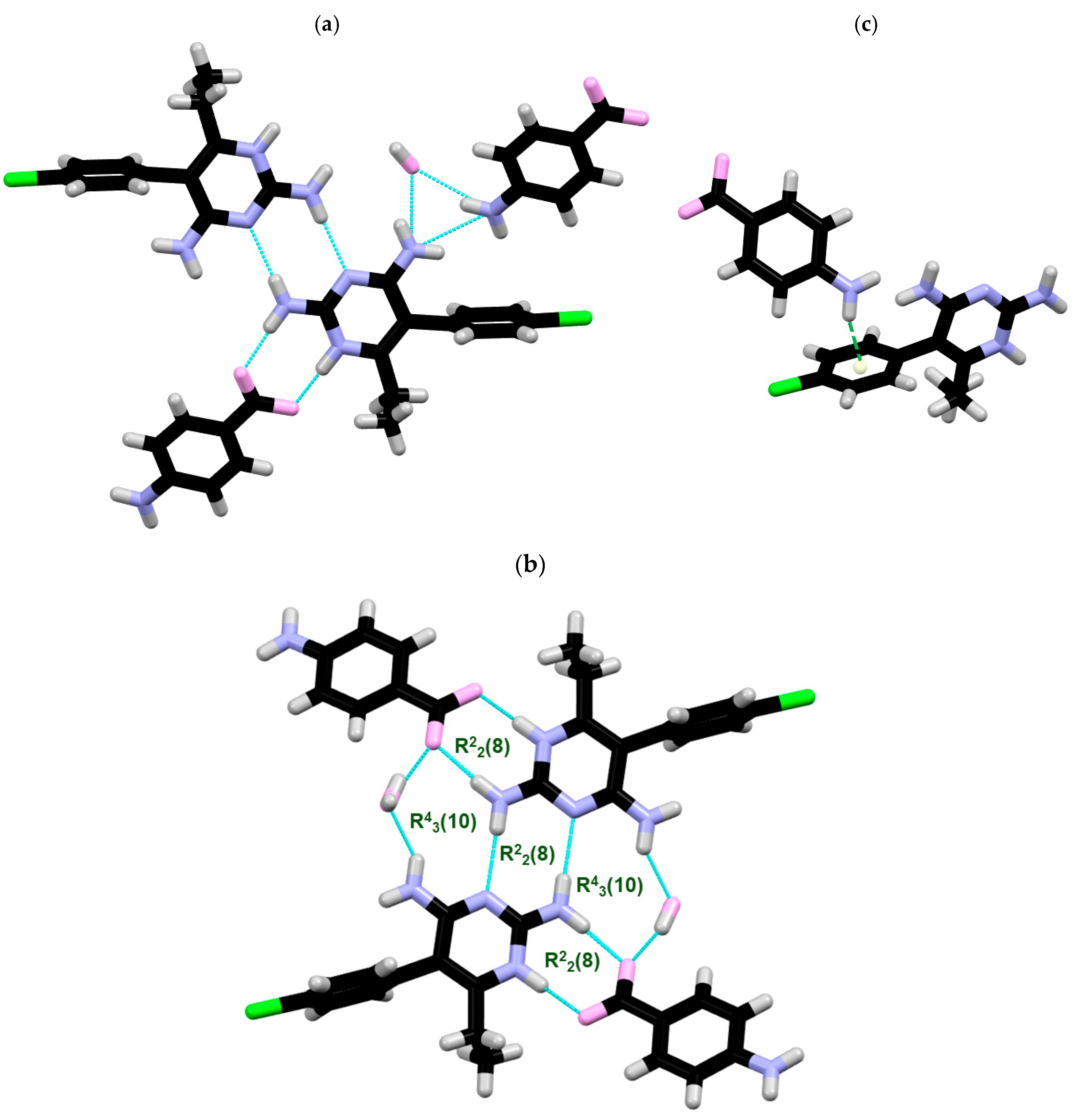

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. SCXRD

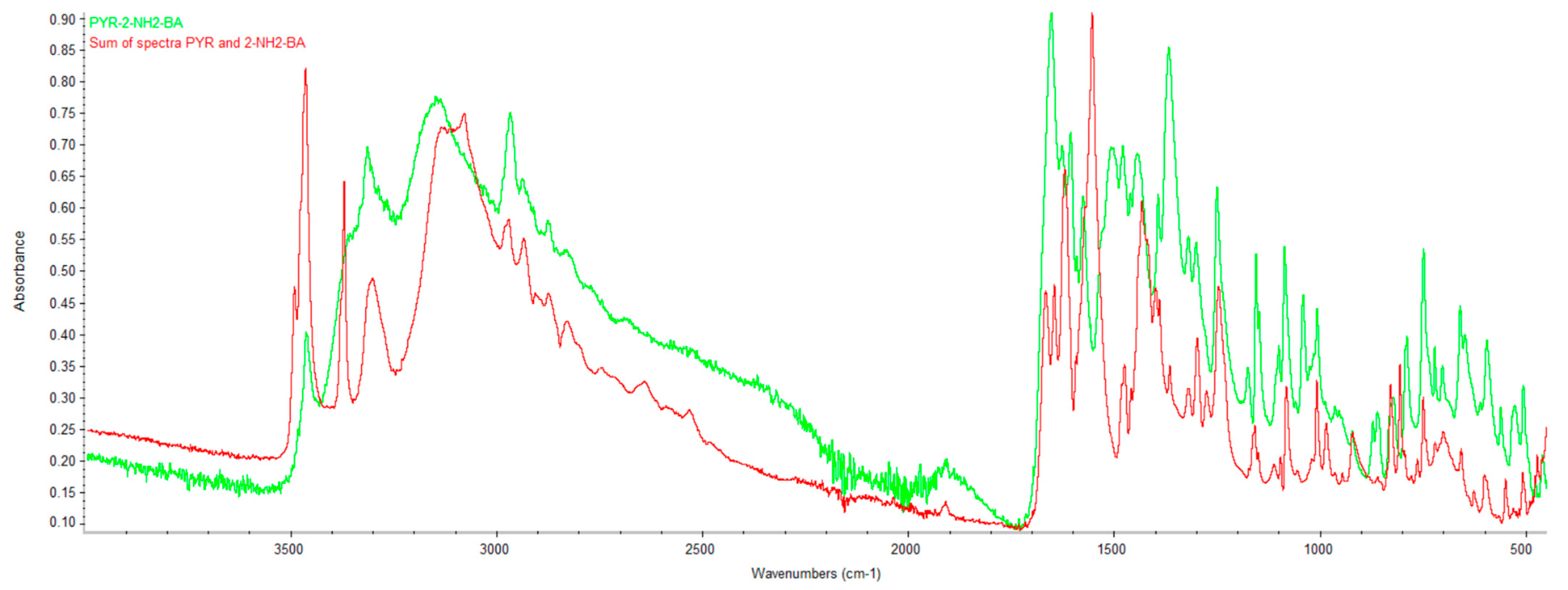

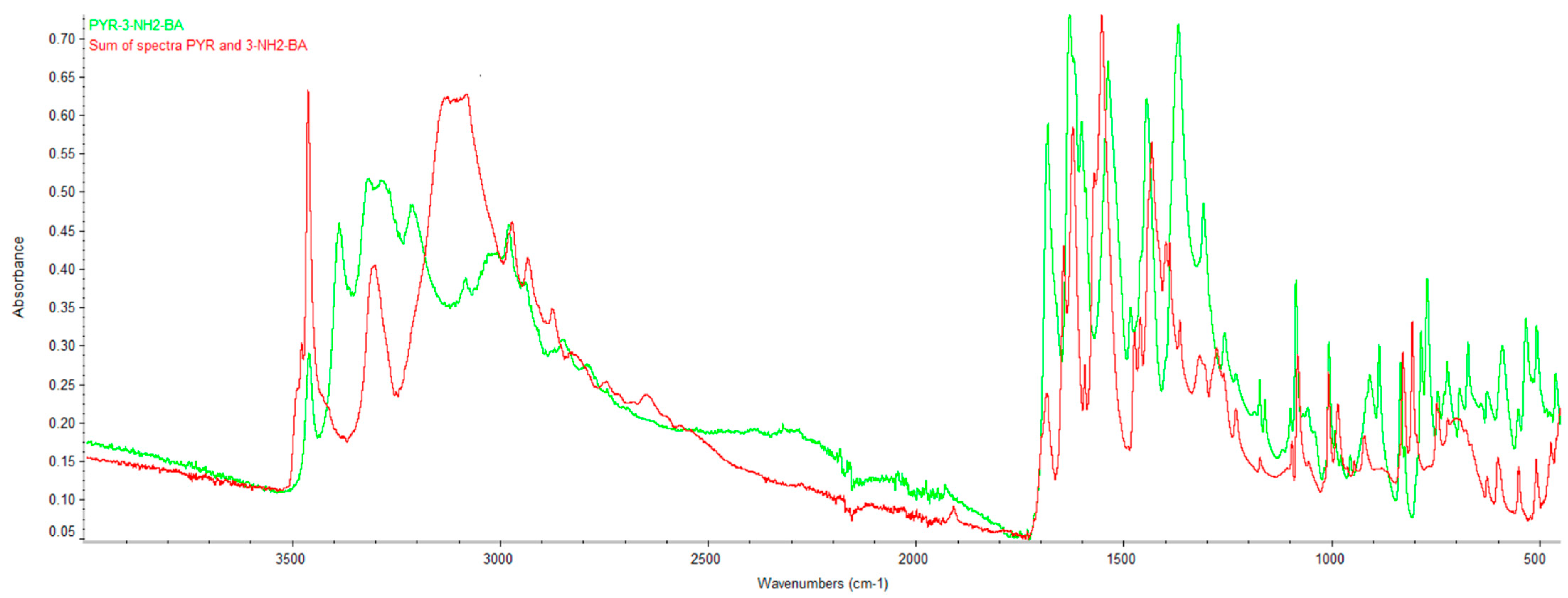

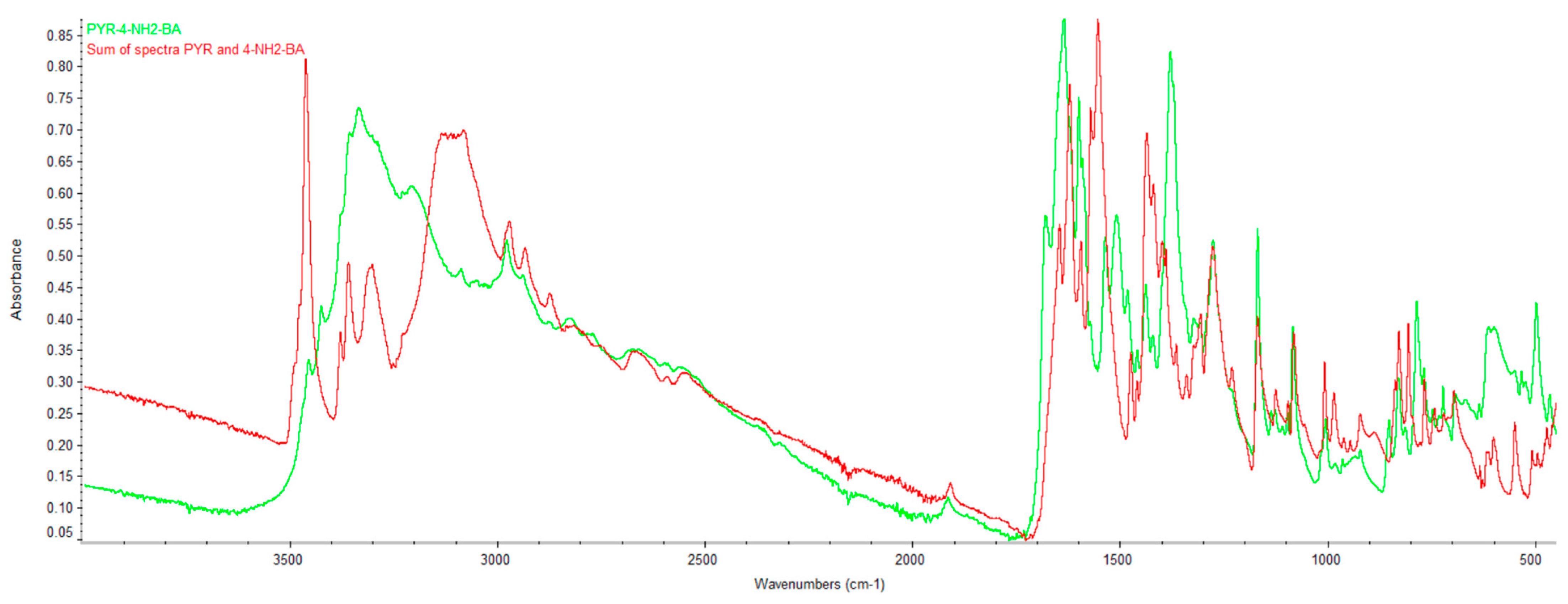

2.2. Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

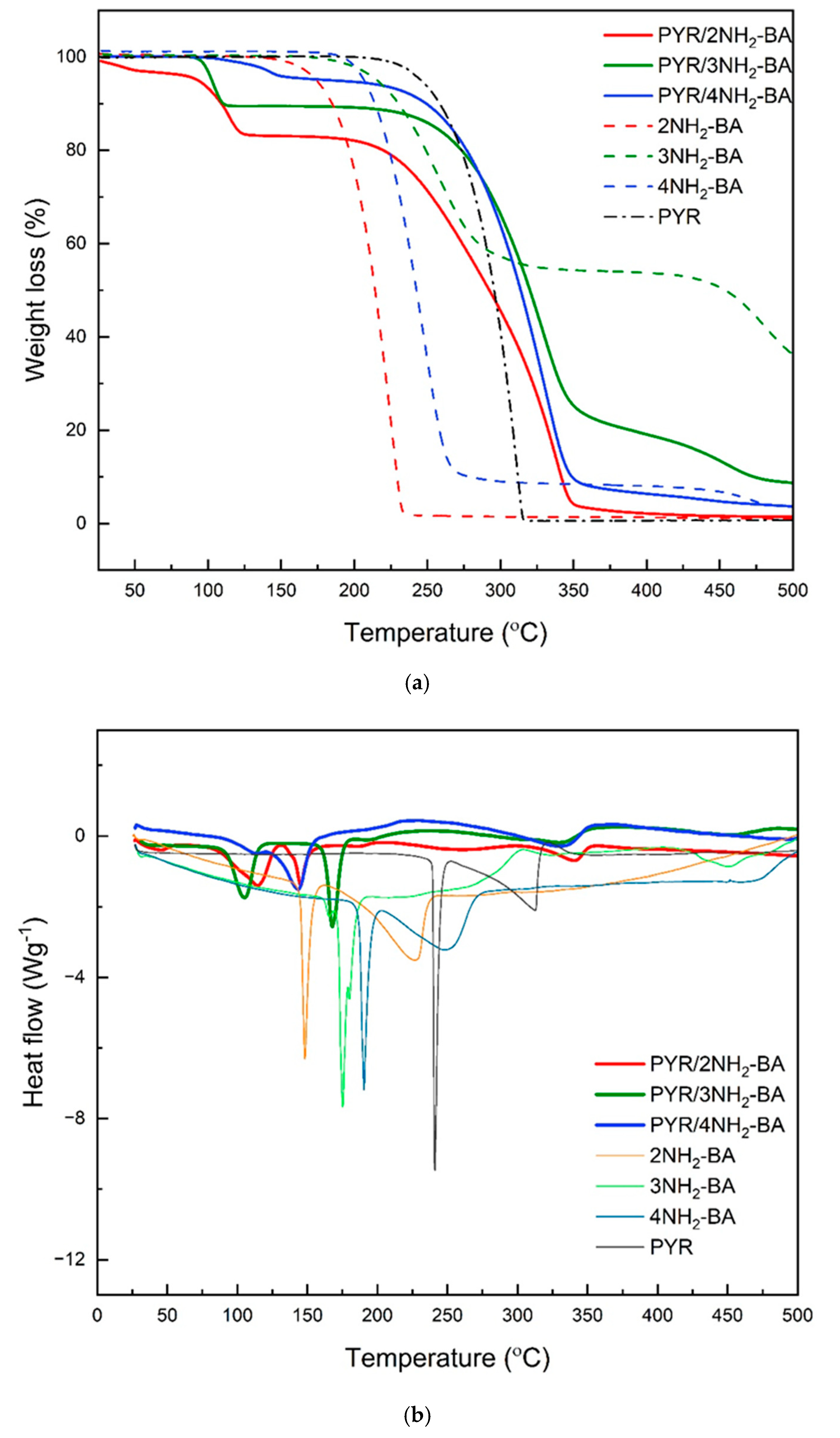

2.3. Thermal Analysis (DSC/TG)

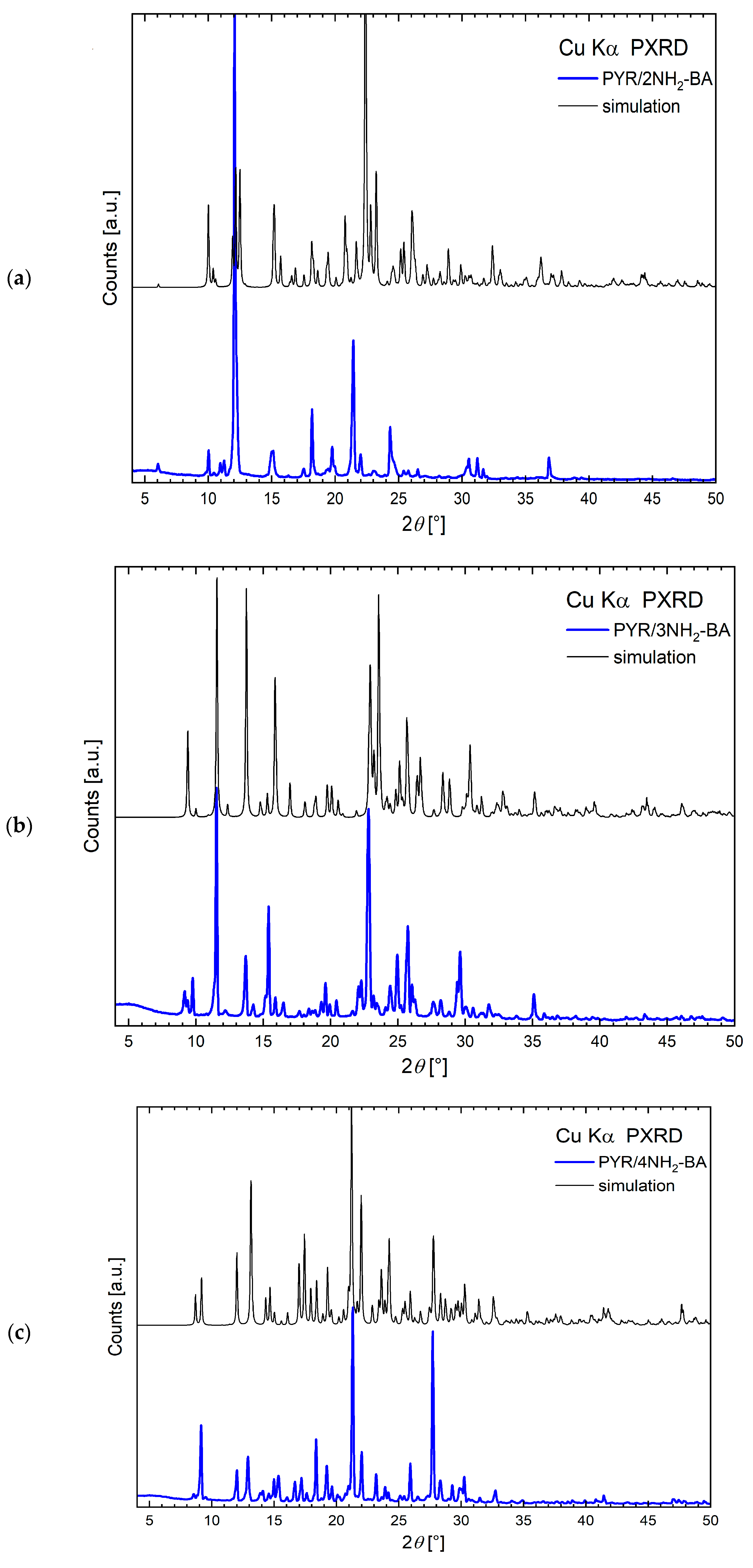

2.4. Powder X-Ray Diffraction

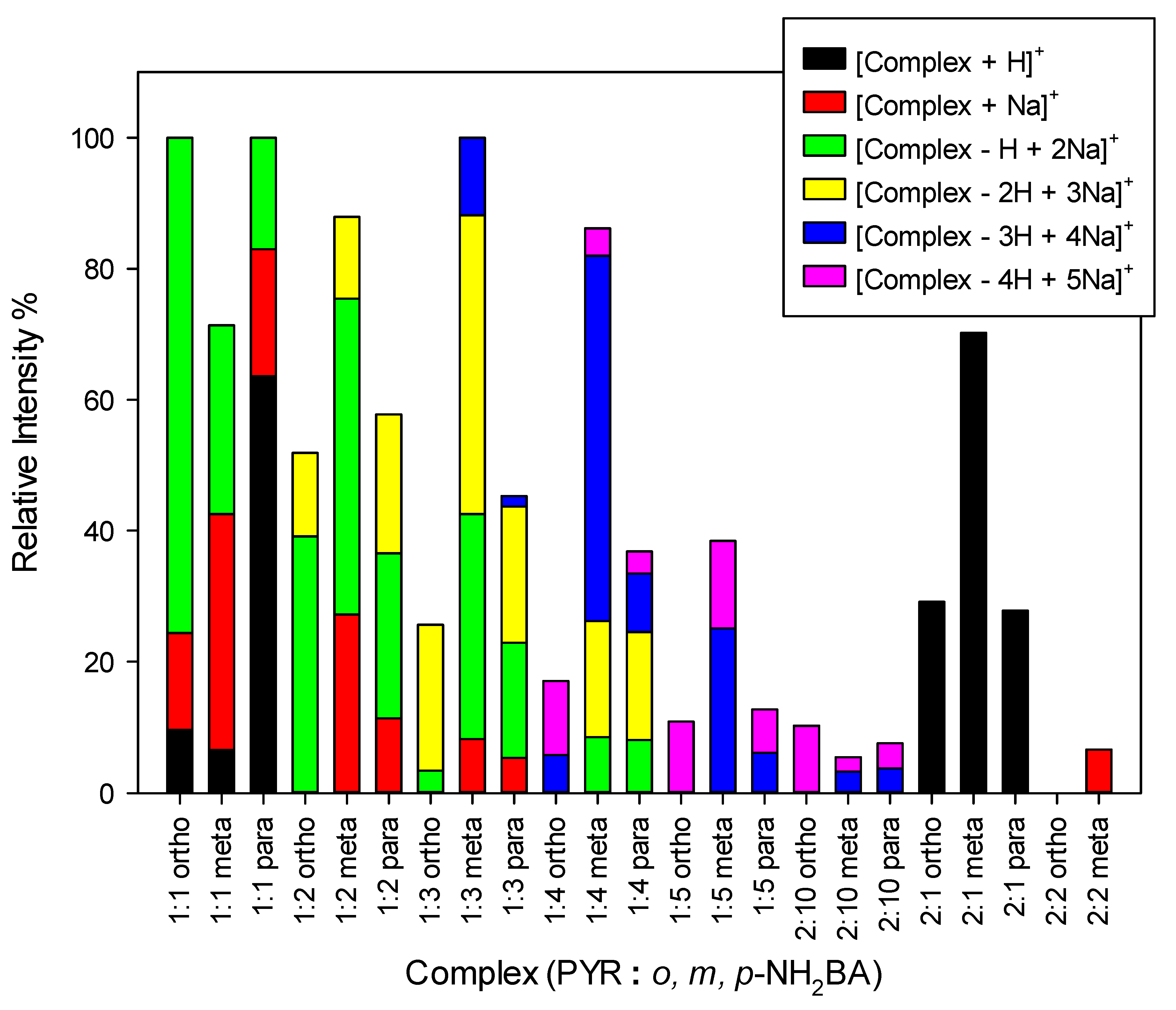

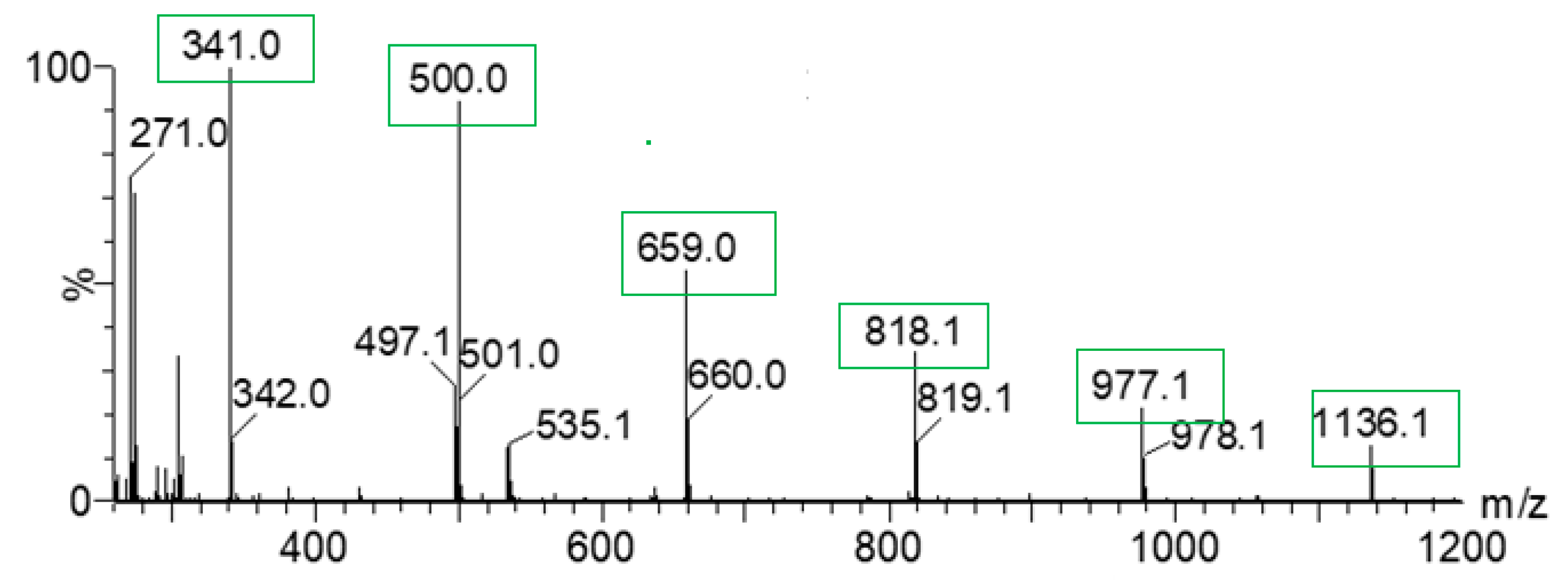

2.5. Mass Spectrometry Measurements

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Solution Crystallization

3.3. Single-Crystal X-Ray Diffraction

3.4. Infrared Spectroscopy

3.5. Thermal Analysis

3.6. Powder X-Ray Diffraction

3.7. Mass Spectrometry

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heppler, L.N.; Attarha, S.; Persaud, R.; Brown, J.I.; Wang, P.; Petrova, B.; Tošić, I.; Burton, F.B.; Flamand, Y.; Walker, S.R.; et al. The antimicrobial drug pyrimethamine inhibits STAT3 transcriptional activity by targeting the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A.C. Targeting DHFR in parasitic protozoa. Drug Discov. Today 2005, 10, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompis, I.M.; Islam, K.; Then, R.L. DNA and RNA Synthesis: Antifolates. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 593–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzila, A. The past, present and future of antifolates in the treatment of Plasmodium falciparum infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemotherap. 2006, 57, 1043–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Qin, Y.; Zhai, D.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, J.; Tang, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, K.; Yang, L.; Chen, S.; et al. Antimalarial Drug Pyrimethamine Plays a Dual Role in Antitumor Proliferation and Metastasis through Targeting DHFR and TP. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.I.; Persaud, R.; Iliev, P.; Karmacharya, U.; Attarha, S.; Sahile, H.; Olsen, J.E.; Hanke, D.; Idowu, T.; Frank, D.A.; et al. Investigating the anti-cancer potential of pyrimethamine analogues through a modern chemical biology lens. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 264, 115971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tommasino, C.; Gambardella, L.; Buoncervello, M.; Griffin, R.J.; Golding, B.T.; Alberton, M.; Macchi, D.; Spada, M.; Cerbelli, B.; d’Amati, G.; et al. New derivatives of the antimalarial drug Pyrimethamine in the control of melanoma tumor growth: An in vitro and in vivo study. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 35, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuka, P.M.; Njaria, P.; Mayoka, G.; Funjika, E. Emerging Drug Targets for Antimalarial Drug Discovery: Validation and Insights into Molecular Mechanisms of Function. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 838–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhang, J.; Lai, F.; Feng, J.; Wu, G.; Xia, J.; Zhang, W.; Han, Z.; Zhang, C.; et al. Exploration and Biological Evaluation of 1,3-Diamino-7H-pyrrol[3,2-f]quinazoline Derivatives as Dihydrofolate Reductase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 13946–13967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitipamula, S.; Banerjee, R.; Bansal, A.K.; Biradha, K.; Cheney, M.L.; Roy Choudhury, A.; Desiraju, G.R.; Dikundwar, A.G.; Dubey, R.; Duggirala, N.; et al. Polymorphs, Salts, and Cocrystals: What’s in a Name? Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 2147–2152, Erratum in Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 8, 4290–4291. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, D.J.; Steed, J.W. Pharmaceutical cocrystals, salts and multicomponent systems; intermolecular interactions and property based design. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2017, 117, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingos, S.; André, V.; Quaresma, S.; Martins, I.C.B.; Minas da Piedade, M.F.; Duarte, M.T. New forms of old drugs: Improving without changing. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 830–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, N.; Sethuraman, V.; Muthiah, P.T.; Luger, P.; Weber, M. Crystal Engineering of Organic Salts: Hydrogen-Bonded Supramolecular Motifs in Pyrimethamine Hydrogen Glutarate and Pyrimethamine Formate. Cryst. Growth Des. 2002, 2, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethuraman, V.; Stanley, N.; Muthiah, P.T.; Sheldrick, W.S.; Winter, M.; Luger, P.; Weber, M. Isomorphism and Crystal Engineering: Organic Ionic Ladders Formed by Supramolecular Motifs in Pyrimethamine Salts. Cryst. Growth Des. 2003, 3, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delori, A.; Galek, P.T.A.; Pidcock, E.; Jones, W. Quantifying Homo- and Heteromolecular Hydrogen Bonds as a Guide for Adduct Formation. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 6835–6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, P.; Muthiah, P.T.; Row, T.N.G.; Thiruvenkatam, V. Hydrogen bonding in pyrimethamine hydrogen adipate. Acta Cryst. 2007, E63, o4065–o4066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramani, K.; Muthiah, P.T. Hydrogen-bonding Patterns in Pyrimethaminium Picolinate. Anal. Sci. 2008, 24, x251–x252, Erratum in Anal. Sci. 2008, 24, x309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramani, K.; Muthiah, P.T.; Bocelli, G.; Cantoni, A. Pyrimethaminium nicotinate monohydrate. Acta Cryst. 2007, E63, o4452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faroque, M.U.; Mehmood, A.; Noureen, S.; Ahmed, M. Crystal engineering and electrostatic properties of co-crystals of pyrimethamine with benzoic acid and gallic acid. J. Mol. Struc. 2020, 1214, 128183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceborska, M.; Kędra-Królik, K.; Narodowiec, J.; Dąbrowa, K. Influence of Hydroxyl Group Position and Substitution Pattern of Hydroxybenzoic Acid on the Formation of Molecular Salts with the Antifolate Pyrimethamine. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021, 21, 6714–6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, C.; Bouchet, C.; Manyara, G.; Walsh, N.; McArdle, P.; Erxleben, A. Salts, Binary and Ternary Cocrystals of Pyrimethamine: Mechanosynthesis, Solution Crystallization, and Crystallization from the Gas Phase. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021, 21, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delori, A.; Galek, P.T.A.; Pidcock, E.; Patniac, M.; Jones, W. Knowledge-based hydrogen bond prediction and the synthesis of salts and cocrystals of the anti-malarial drug pyrimethamine with various drug and GRAS molecules. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 2916–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darious, S.R.; Muthiah, P.T.; Perdih, F. Supramolecular hydrogen-bonding patterns in salts of the antifolate drugs trimethoprim and pyrimethamine. Acta Cryst. 2018, C74, 487–503. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, N.; Muthiah, P.T.; Geib, S.J.; Luger, P.; Weber, M.; Messerschmidt, M. The novel hydrogen bonding motifs and supramolecular patterns in 2,4-diaminopyrimidine–nitrobenzoate complexes. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 7201–7210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanigaimani, K.; Muthiah, P.T.; Lynch, D.E. Hydrogen-bonding patterns in the cocrystal 2-amino-4,6-dimethoxypyrimidine–anthranilic acid (1/1). Acta Cryst. 2008, E64, o107–o108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arman, H.D.; Kaulgud, T.; Miller, T.; Tiekink, E.R.T. Persistence of the {…HOCO…HCN} heterosynthon in the co-crystals formed between anthranilic acid and three bipyridine-containing molecules. Z. Krist. 2012, 227, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madusanka, N.; Eddleston, M.D.; Arhangelskis, M.; Jones, M. Polymorphs, hydrates and solvates of a co-crystal of caffeine with anthranilic acid. Acta Cryst. 2014, B70, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, F.; Joester, M.; Rademann, K.; Emmerling, F. Survival of the Fittest: Competitive Co-crystal Reactions in the Ball Mill. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 14969–14974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaló, M.; Cunha, A.E.S.; Luís, J.P.; Quaresma, S.; Fernandes, A.; André, V.; Duarte, M.T. Sparfloxacin Multicomponent Crystals: Targeting the Solubility of Problematic Antibiotics. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021, 21, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.-L.; Li, S.; Chen, J.-M.; Lu, T.-B. Improving the Membrane Permeability of 5-Fluorouracil via Cocrystallization. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 4430–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangala, V.R.; Chow, P.S.; Tan, R.B.H. Co-Crystals and Co-Crystal Hydrates of the Antibiotic Nitrofurantoin: Structural Studies and Physicochemical Properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 2012, 12, 85925–85938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Anthal, S.; Srijana, P.J.; Narayana, B.; Sarojini, B.; Likhitha, K.; Kamal, U.; Kant, R. Novel supramolecular co-crystal of 3-aminobenzoic acid with 4-acetyl-pyridine: Synthesis, X-ray structure, DFT and Hirshfeld surface analysis. J. Mol. Struc. 2022, 1262, 133061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Gong, L.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, L.; Yang, S.; Yang, D.; Lu, Y.; Du, G. New Cocrystals of Ligustrazine: Enhancing Hygroscopicity and Stability. Molecules 2024, 29, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, A.; Khan, E.; Srivastava, K.; Sinha, K.; Tandon, P.; Vangala, V.R. Study of molecular interactions and chemical reactivity of the nitrofurantoin–3-aminobenzoic acid cocrystal using quantum chemical and spectroscopic (IR, Raman, 13C SS-NMR) approaches. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 3921–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harriss, B.I.; Vella-Zarb, L.; Wilson, C.; Radosavljevic Evans, I. Furosemide Cocrystals: Structures, Hydrogen Bonding, and Implications. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddileti, D.; Jayabun, S.K.; Nangia, A. Soluble Cocrystals of the Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitor Febuxostat. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 3188–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandaru, J.S.; Malothu, N.; Akkinepally, R.R. Characterization and Solubility Studies of Pharmaceutical Cocrystals of Eprosartan Mesylate. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, K.; Minkov, V.S.; Kumar Namila, K.; Derevyannikova, E.; Losev, E.; Nangia, A.; Boldyreva, E.V. Novel Synthons in Sulfamethizole Cocrystals: Structure–Property Relations and Solubility. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 3498–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.A.; Sardo, M.; Mafra, L.; Choquesillo-Lazarte, D.; Masciocchi, N. X-Ray and NMR Crystallography Studies of Novel Theophylline Cocrystals Prepared by Liquid Assisted Grinding. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 3674–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singaraju, A.B.; Nguyen, K.; Gawędzki, P.; Herald, F.; Meyer, G.; Wentworth, D.; Swenson, D.C.; Stevens, L.L. Combining Crystal Structure and Interaction Topology for Interpreting Functional Molecular Solids: A Study of Theophylline Cocrystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 6741–6751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, R.; Qiu, S.; Chen, Z.; Rao, W.; Chen, S.; You, Y.; Lü, J.; Xu, L.; et al. Cocrystal of Sulfamethazine and p-Aminobenzoic Acid: Structural Establishment and Enhanced Antibacterial Properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 2455–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandiño, O.E.; Reviglio, L.; Linck, Y.G.; Monti, G.A.; Marcos Valdez, M.M.; Faudone, S.N.; Caira, M.R.; Sperandeo, N.R. Novel Cocrystals and Eutectics of the Antiprotozoal Tinidazole: Mechanochemical Synthesis, Cocrystallization, and Characterization. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20, 2930–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Pop, M.; Kacso, I.; Grosu, I.G.; Miclăuş, M.; Vodnar, D.; Lung, I.; Filip, G.A.; Olteanu, E.D.; Moldovan, R.; et al. Ketoconazole-p-aminobenzoic Acid Cocrystal: Revival of an Old Drug by Crystal Engineering. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deka, P.; Gogoi, D.; Althubeiti, K.; Rao, D.R.; Thakuria, R. Mechanosynthesis, Characterization, and Physicochemical Property Investigation of a Favipiravir Cocrystal with Theophylline and GRAS Coformers. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021, 21, 4417–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, T.; Shankland, K.; Al-Obaidi, H. Preparation and formulation of progesterone para-aminobenzoic acid co-crystals with improved dissolution and stability. Europ. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2024, 196, 114202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, N.; He, B.; Jia, Y.; Yang, C.; Wang, J.; Li, M. The mechanism of binding with the α-glucosidase in vitro and the evaluation on hypoglycemic effect in vivo: Cocrystals involving synergism of gallic acid and conformer. Europ. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 156, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Gülbakan, B.; Weidmann, S.; Fagerer, S.R.; Ibáñez, A.J.; Zenobi, R. Applying mass spectrometry to study non-covalent biomolecule complexes. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2016, 35, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas-Hinestroza, J.L.; Bueno, M.; Ibáñez, E.; Cifuentes, A. Recent advances in mass spectrometry studies of non-covalent complexes of macrocycles—A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1081, 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.H.; Kennard, O.; Watson, D.G.; Brammer, L.; Orpen, A.G.; Taylor, R. Tables of Bond Lengths determined by X-Ray and Neutron Diffraction. Part I. Bond Lengths in Organic Compounds. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1987, 12, S1–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrysAlisPRO, 1.171.40.84a, Oxford Diffraction/Agilent Technologies UK Ltd.: Yarnton, UK, 2020.

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. A 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Cryst. 2015, C71, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Macrae, C.F.; Sovago, I.; Cottrell, S.J.; Galek, P.T.A.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Platings, M.; Shields, G.P.; Stevens, J.S.; Towler, M.; et al. Mercury 4.0: From visualization to analysis, design and prediction. J. Appl. Cryst. 2020, 53, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spek, A.L. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003, 36, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DC(7)–O(1) (Å) | DC(7)–O(2) (Å) | ΔDC–O (Å) | Proton Transfer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PYR/2NH2-BA | 1.253 (2) | 1.270 (2) | 0.017 | yes |

| PYR/3NH2-BA | 1.256 (2) | 1.258 (2) | 0.002 | yes |

| PYR/4NH2-BA | 1.260 (2) | 1.268 (2) | 0.008 | yes |

| D—H⋯A | d(D—H) Å | d(H⋯A) Å | d(D⋯A) Å | <(D—H⋯A) o | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | O1–H1S⋯O1B (a) | 0.82 | 2.00 | 2.811 (7) | 171 |

| 2. | N2A–H2A1⋯O1S (b) | 0.86 | 2.00 | 2.846 (6) | 168 |

| 3. | N2A–H2A1⋯O1S’ (b) | 0.86 | 2.19 | 3.03 (1) | 165 |

| 4. | N2A–H2A2⋯O1B9 (c) | 0.86 | 1.94 | 2.790 (4) | 171 |

| 5. | N4A–H4A1⋯N3A (d) | 0.86 | 2.16 | 3.015 (3) | 175 |

| 6. | N4A–H4A2⋯O1S (e) | 0.86 | 2.18 | 2.844 (7) | 134 |

| 7. | N4A–H4A2⋯O1S’ (e) | 0.86 | 2.27 | 2.96 (1) | 138 |

| 8. | N1B–H1B2⋯O2B | 0.86 | 2.05 | 2.682 (3) | 130 |

| 9. | C1S–H1S2⋯O2W | 0.97 | 1.97 | 2.825 (9) | 145 |

| 10. | C4B–H4A⋯Cl1 (a) | 0.93 | 2.75 | 3.466 (3) | 135 |

| 11. | C12A–H12A⋯O2W (d) | 0.93 | 2.58 | 3.499 (6) | 172 |

| D—H⋯A | d(D—H) Å | d(H⋯A) Å | d(D⋯A) Å | <(D—H⋯A) o | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | O1E–H1E⋯O2B | 0.84 | 1.84 | 2.665 (2) | 167 |

| 2. | N1A–H1W⋯O1B (a) | 0.91 (2) | 1.72 (2) | 2.619 (2) | 168 (2) |

| 3. | N1B–H1X⋯O2B (b) | 0.98 (3) | 2.59 (3) | 3.563 (2) | 174 (2) |

| 4. | N2A–H2X⋯O2B(a) | 0.88 (2) | 2.01 (2) | 2.881 (2) | 174 (2) |

| 5. | N2A–H2Z⋯O1E (c) | 0.87 (2) | 2.11 (2) | 2.963 (2) | 168 (2) |

| 6. | N4A–H4X⋯O1E | 0.88 (2) | 2.09 (2) | 2.833 (2) | 142 (2) |

| 7. | N4A–H4Z⋯N3A (c) | 0.90 (2) | 2.08 (2) | 2.971 (2) | 171 (2) |

| 8. | C11A–H11A⋯Cg(a) (b) | 0.95 | 2.985 | 3.819 | 147 |

| D—H ⋯A | d(D—H) Å | d(H⋯A) Å | d(D⋯A) Å | <(D—H⋯A) o | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | N1A–H1N⋯O2B (a) | 0.94 (2) | 1.81 (2) | 2.738 (2) | 171 (2) |

| 2. | O1W–H1V⋯O1B (b) | 0.86 (3) | 1.83 (3) | 2.662 (2) | 164 (2) |

| 3. | O1W–H1W⋯O2B | 0.90 (3) | 1.88 (3) | 2.730 (2) | 156 (3) |

| 4. | N2A–H2Y⋯N3A (c) | 0.88 | 2.21 | 3.084 (2) | 173 |

| 5. | N2A–H2X⋯O1B (a) | 0.88 | 1.88 | 2.761 (2) | 174 |

| 6. | N4A–H4Y⋯O1W | 0.88 | 2.11 | 2.818 (2) | 137 |

| 7. | N4A–H4X⋯N1B (d) | 0.88 | 2.33 | 3.039 (2) | 138 |

| 8. | N1B–H1R⋯O1W (a) | 0.88 | 2.23 | 3.069 (2) | 158 |

| 9. | N1B–H1R⋯N4A (a) | 0.88 | 2.43 | 3.039 (2) | 127 |

| 10. | C9B–H9A⋯O1B (e) | 0.95 | 2.59 | 3.340 (2) | 137 |

| 11. | C11A–H11A⋯N4A (f) | 0.95 | 2.55 | 3.579 (2) | 164 |

| 12 | N1B(H1P)⋯Cg(a)) (g) | 0.88 | 3.086 | 3.722 | 131 |

| TGA Curves | Desolvation Step (up to 160 °C) Weight (%) | Salt Decomposition Weight (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrates | ||||

| PYR | - | 99.5 | ||

| 2NH2-BA | - | 99.5 | ||

| 3NH2-BA | - | 46.2 | ||

| 4NH2-BA | - | 92.8 | ||

| Salts | ||||

| PYR/2NH2-BA | 2.4 | 13.7 | 31.2 | 50.5 |

| PYR/3NH2-BA | 10.7 | 69.1 | 12.4 | |

| PYR/4NH2-BA | 1.1 | 3.5 | 88.6 | 3.8 |

| PYR/2NH2-BA | PYR/3NH2-BA | PYR/4NH2-BA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCDC | 2271560 | 2271562 | 2271563 |

| Chem formula | C12H14N4Cl × C7H6NO2 × C2H6O × H2O | C12H14N4Cl × C7H6NO2 × C2H6O | C12H14N4Cl × C7H6NO2 × H2O |

| Formula Wt | 449.93 | 431.92 | 403.86 |

| Cryst syst | triclinic | monoclinic | monoclinic |

| Space group | P-1 | P21/n | P21/c |

| a (Å) | 8.7493 (6) | 11.9619 (2) | 9.7247 (3) |

| b (Å) | 9.5143 (7) | 15.3108 (3) | 15.5035 (5) |

| c (Å) | 15.110 (1) | 12.0383 (2) | 13.6052 (4) |

| α (o) | 74.650 (6) | ||

| β (o) | 82.736 (6) | 94.977 (2) | 97.473 (3) |

| γ (o) | 73.208 (6) | ||

| V (Å3) | 1160.3 (2) | 2196.46 (7) | 2033.79 (11) |

| Z | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| D (g × cm−3) | 1.288 | 1.306 | 1.319 |

| T (K) | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| μ (mm−1) | 1.763 | 1.807 | 1.916 |

| No. of reflections measured | 10932 | 8478 | 7675 |

| No. of independent reflections | 4380 | 4100 | 3775 |

| Rint | 0.023 | 0.021 | 0.02 |

| Final R indices (I > 2s(I)) | R = 0.0646 wR = 0.1780 | R = 0.036 wR = 0.092 | R = 0.036 wR = 0.094 |

| Final R indices (all data) | R = 0.0686 wR = 0.1822 | R = 0.042 wR = 0.097 | R = 0.040 wR = 0.097 |

| GOF | 1.052 | 1.035 | 1.027 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cichocka, K.; Zimnicka, M.; Kędra, K.; Gajek, A.; Ceborska, M. Salts of Antifolate Pyrimethamine with Isomeric Aminobenzoic Acids: Exploring Packing Interactions and Pre-Crystallization Aggregation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010180

Cichocka K, Zimnicka M, Kędra K, Gajek A, Ceborska M. Salts of Antifolate Pyrimethamine with Isomeric Aminobenzoic Acids: Exploring Packing Interactions and Pre-Crystallization Aggregation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010180

Chicago/Turabian StyleCichocka, Karolina, Magdalena Zimnicka, Karolina Kędra, Arkadiusz Gajek, and Magdalena Ceborska. 2026. "Salts of Antifolate Pyrimethamine with Isomeric Aminobenzoic Acids: Exploring Packing Interactions and Pre-Crystallization Aggregation" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010180

APA StyleCichocka, K., Zimnicka, M., Kędra, K., Gajek, A., & Ceborska, M. (2026). Salts of Antifolate Pyrimethamine with Isomeric Aminobenzoic Acids: Exploring Packing Interactions and Pre-Crystallization Aggregation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010180