Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the ClHMGB Gene Family in Watermelon Under Abiotic Stress and Fusarium oxysporum Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Synteny Analysis of the ClHMGB Genes in Watermelon

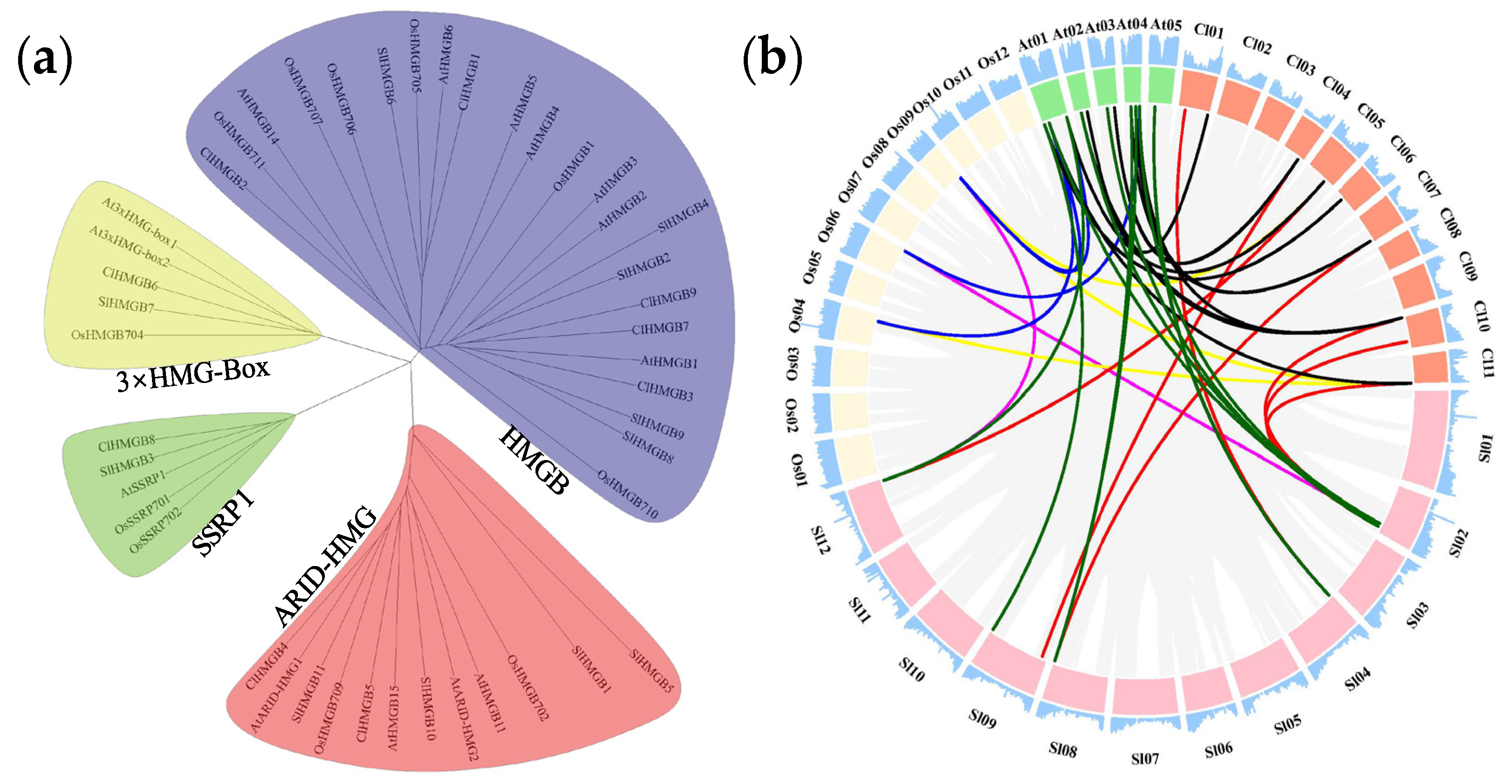

2.2. Phylogenetic and Syntenic Analyses of the ClHMGBs

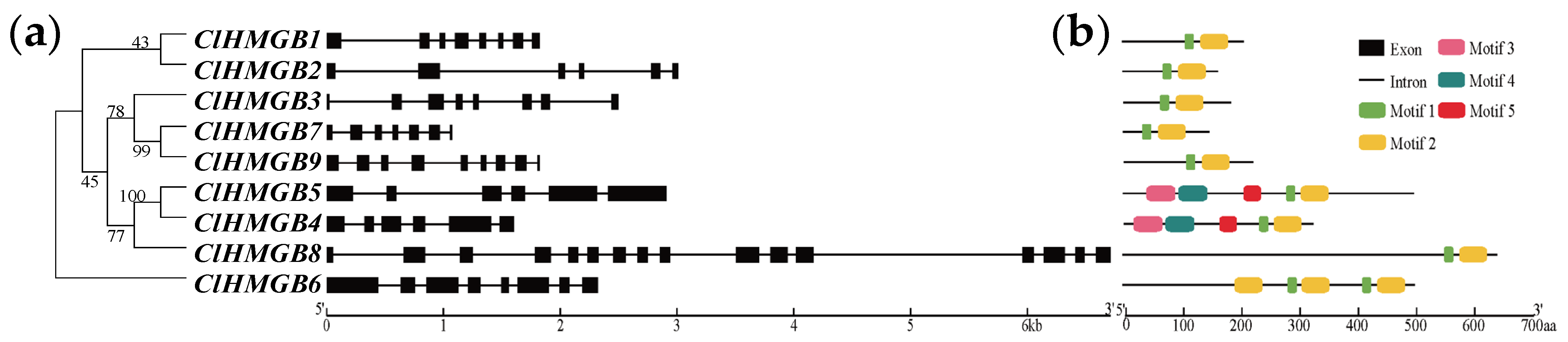

2.3. Gene Structure, Conserved Domains and Cis-Acting Regulatory Elements of the ClHMGBs

2.4. Profiles of Tissue-Specific Expression Patterns of ClHMGBs

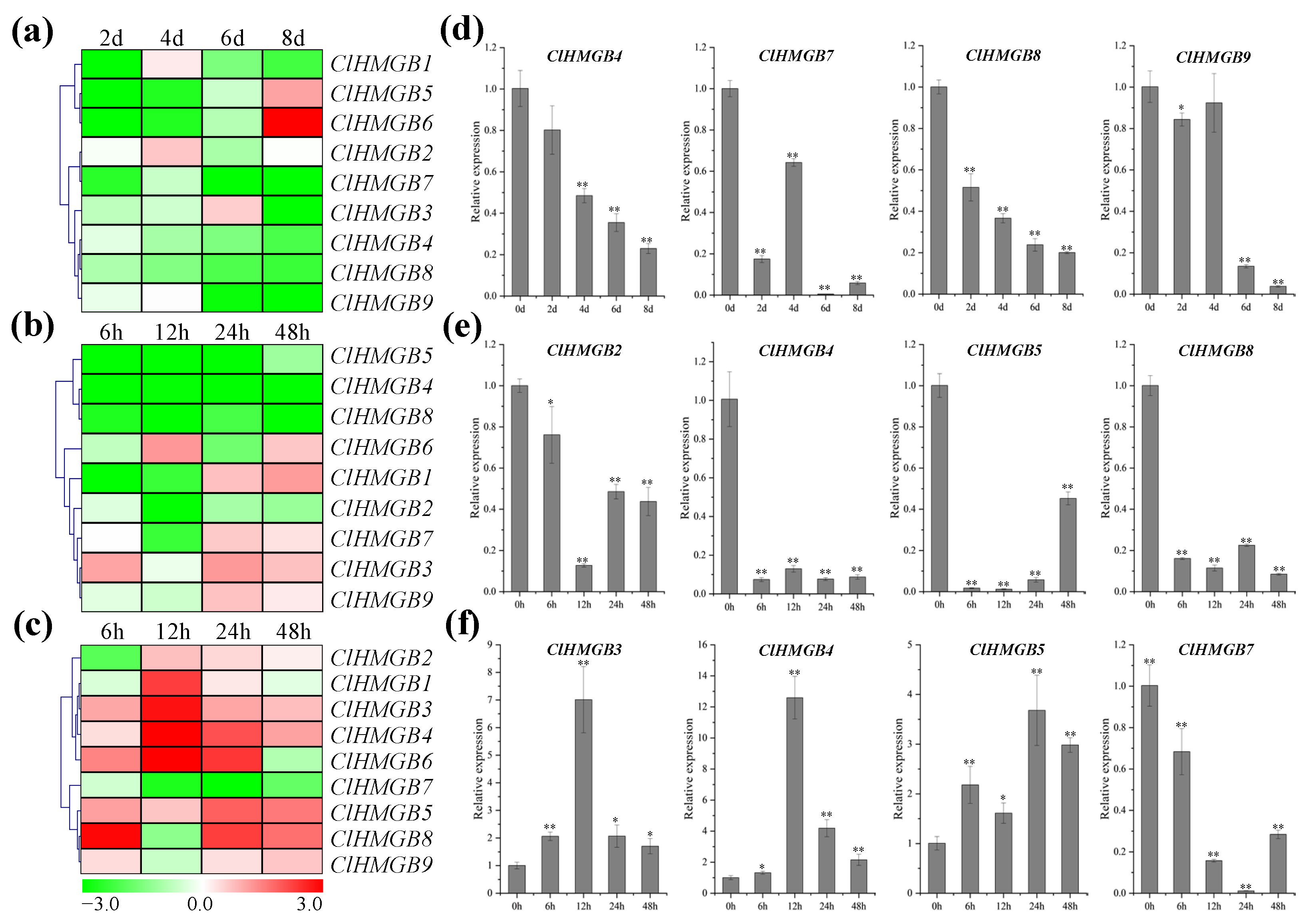

2.5. Patterns of Expression of ClHMGB Genes in Response to Drought, Low-Temperature, and Salt Stress

2.6. Expression Patterns of the ClHMGB Genes in Response to Infection with Fon

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials, as Well as Abiotic and Biotic Stress Treatments

4.2. Identification and Characterization of HMGB Genes in Watermelon

4.3. Phylogenetic, Syntenic, Gene Structure, Conserved Domain, and Cis-Acting Regulatory Element Analyses

4.4. RNA Extraction and Expression Pattern Analysis

4.5. Subcellular Localization

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HMGB | High-Mobility Group B |

| Fon | Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum |

| Pi | Phosphorus |

| PSR | Phosphate starvation response |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| DAMP | Damage-associated molecular pattern |

| Xoo | Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae |

| dpt | Days post-treatment |

| hpt | Hours post-treatment |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

References

- Chen, J.; Li, H.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Q. The role of high mobility group proteins in cellular senescence mechanisms. Front. Aging 2024, 5, 1486281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmanabhan, S.; Monera-Girona, A.J.; Pérez-Castaño, R.; Bastida-Martínez, E.; Pajares-Martínez, E.; Bernal-Bernal, D.; Galbis-Martínez, M.L.; Polanco, M.C.; Iniesta, A.A.; Fontes, M.; et al. Light-Triggered Carotenogenesis in Myxococcus xanthus: New Paradigms in Photosensory Signaling, Transduction and Gene Regulation. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Xi, Y.; Kim, J.; Sung, S. Chromatin architectural proteins regulate flowering time by precluding gene looping. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papantonis, A. HMGs as rheostats of chromosomal structure and cell proliferation. Trends Genet. 2021, 37, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, P.I.; Martin Vazquez, E.; López-Noriega, L.; Fuente-Martín, E.; Mellado-Gil, J.M.; Franco, J.M.; Cobo-Vuilleumier, N.; Guerrero Martínez, J.A.; Romero-Zerbo, S.Y.; Perez-Cabello, J.A.; et al. The metabesity factor HMG20A potentiates astrocyte survival and reactive astrogliosis preserving neuronal integrity. Theranostics 2021, 11, 6983–7004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, D.K.; Hegde, C.; Bhattacharyya, M.K. Identification of multiple novel genetic mechanisms that regulate chilling tolerance in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1094462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garabedian, A.; Jeanne Dit Fouque, K.; Chapagain, P.P.; Leng, F.; Fernandez-Lima, F. AT-hook peptides bind the major and minor groove of AT-rich DNA duplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 2431–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Kram, V.; Furusawa, T.; Duverger, O.; Chu, E.Y.; Nanduri, R.; Ishikawa, M.; Zhang, P.; Amendt, B.A.; Lee, J.S.; et al. Epigenetic Regulation of Ameloblast Differentiation by HMGN Proteins. J. Dent. Res. 2023, 103, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, R.; Kundu, A.; Chaudhuri, S. High mobility group proteins: The multifaceted regulators of chromatin dynamics. Nucleus 2018, 61, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D.J.; Hein, A.E.; Wuttke, D.S.; Batey, R.T. The DNA binding high mobility group box protein family functionally binds RNA. WIREs RNA 2023, 14, e1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfab, A.; Grønlund, J.T.; Holzinger, P.; Längst, G.; Grasser, K.D. The Arabidopsis Histone Chaperone FACT: Role of the HMG-Box Domain of SSRP1. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 2747–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Han, P.; Han, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, G.; Leng, X. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of VviYABs Family Reveal Its Potential Functions in the Developmental Switch and Stresses Response During Grapevine Development. Front. Genet. 2022, 12, 762221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinpongpanich, A.; Phean-O-Pas, S.; Thongchuang, M.; Qu, L.-J.; Buaboocha, T. C-terminal extension of calmodulin-like 3 protein from Oryza sativa L.: Interaction with a high mobility group target protein. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2015, 47, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudreau-Lapierre, A.; Klonisch, T.; Nicolas, H.; Thanasupawat, T.; Trinkle-Mulcahy, L.; Hombach-Klonisch, S. Nuclear High Mobility Group A2 (HMGA2) Interactome Revealed by Biotin Proximity Labeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.Y.; Kwak, K.J.; Kang, H. Expression of a High Mobility Group Protein Isolated from Cucumis sativus Affects the Germination of Arabidopsis thaliana under Abiotic Stress Conditions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2008, 50, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasser, K.D. The FACT Histone Chaperone: Tuning Gene Transcription in the Chromatin Context to Modulate Plant Growth and Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Tan, B.; Wu, J.; Gao, C. Screening and functional identification of salt tolerance HMG genes in Betula platyphylla. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 181, 104235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pi, Y.; Fan, J.; Yang, X.; Zhai, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, F.; Ding, J.; Gu, T.; Li, Y.; et al. High mobility group A3 enhances transcription of the DNA demethylase gene SlDML2 to promote tomato fruit ripening. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, Z.; Wang, N.; Tian, X.; Chai, L.; Xie, Z.; Ye, J.; Deng, X. Genome-wide identification of ARID-HMG related genes in citrus and functional analysis of FhARID1 in apomixis and axillary bud development. Hortic. Plant J. 2025, 11, 999–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Tang, H.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Ge, L.; Liu, G.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, Y. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the High-Mobility Group B (HMGB) Gene Family in Plant Response to Abiotic Stress in Tomato. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agresti, A.; Bianchi, M.E. HMGB proteins and gene expression. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2003, 13, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, K.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, Y.O.; Kang, H. Characterization of Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants Overexpressing High Mobility Group B Proteins under High Salinity, Drought or Cold Stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007, 48, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichota, J.; Ritt, C.; Grasser, K.D. Ectopic expression of the maize chromosomal HMGB1 protein causes defects in root development of tobacco seedlings. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 318, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Lu, H.; Lin, R.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, M.; et al. Rice chromatin protein OsHMGB1 is involved in phosphate homeostasis and plant growth by affecting chromatin accessibility. New Phytol. 2023, 240, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michl-Holzinger, P.; Mortensen, S.A.; Grasser, K.D. The SSRP1 subunit of the histone chaperone FACT is required for seed dormancy in Arabidopsis. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, 236, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, K.; Pan, M.; Wen, H.; He, H.; Cai, R.; Pan, J.; et al. FS2 encodes an ARID-HMG transcription factor that regulates fruit spine density in cucumber. J. Integr. Agric. 2025, 24, 1080–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lijsebettens, M.; Grasser, K.D. The role of the transcript elongation factors FACT and HUB1 in leaf growth and the induction of flowering. Plant Signal. Behav. 2014, 5, 715–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wu, X.; Zhu, Z.; Li, T.; Tang, G.; Liu, L.; Wu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Han, Y.; Liu, K.; et al. Bioinformatic and Phenotypic Analysis of AtPCP-Ba Crucial for Silique Development in Arabidopsis. Plants 2024, 13, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Wang, Y.J.; Liang, Y.; Niu, Q.K.; Tan, X.Y.; Chu, L.C.; Chen, L.Q.; Zhang, X.Q.; Ye, D. The ARID-HMG DNA-binding protein AtHMGB15 is required for pollen tube growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2014, 79, 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, R.; Dai, J.; Kong, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J. The transcription factor LpWRKY65 enhances embryogenic capacity through reactive oxygen species scavenging during somatic embryogenesis of larch. Plant Physiol. 2025, 198, kiaf286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Chen, S.; Li, T.; Yu, S.; Zhao, H.; Liu, H.; Luo, L. Overexpression of OsHMGB707, a High Mobility Group Protein, Enhances Rice Drought Tolerance by Promoting Stress-Related Gene Expression. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 711271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Xin, M.; Luan, J.; Liu, D.; Wang, C.; Liu, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, X.; Qin, Z. Overexpression of CsHMGB Alleviates Phytotoxicity and Propamocarb Residues in Cucumber. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chikhirzhina, E.; Tsimokha, A.; Tomilin, A.N.; Polyanichko, A. Structure and Functions of HMGB3 Protein. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xie, Z. Cullin-Conciliated Regulation of Plant Immune Responses: Implications for Sustainable Crop Protection. Plants 2024, 13, 2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, C.; Jiang, S.; Sun, L. Japanese Flounder HMGB1: A DAMP Molecule That Promotes Antimicrobial Immunity by Interacting with Immune Cells and Bacterial Pathogen. Genes 2022, 13, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinesh-Kumar, S.P.; Choi, H.W.; Manohar, M.; Manosalva, P.; Tian, M.; Moreau, M.; Klessig, D.F. Activation of Plant Innate Immunity by Extracellular High Mobility Group Box 3 and Its Inhibition by Salicylic Acid. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ju, Y.; Wu, T.; Kong, L.; Yuan, M.; Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Chu, Z. The clade III subfamily of OsSWEETs directly suppresses rice immunity by interacting with OsHMGB1 and OsHsp20L. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2186–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Y.; Su, W.; Li, W.; Wang, B.; Peng, D.; Gheysen, G.; Peng, H.; Dai, L. The nematode effector calreticulin competes with the high mobility group protein OsHMGB1 for binding to the rice calmodulin-like protein OsCML31 to enhance rice susceptibility to Meloidogyne graminicola. Plant Cell Environ. 2024, 47, 1732–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonmez, C.; Toia, B.; Eickhoff, P.; Matei, A.M.; El Beyrouthy, M.; Wallner, B.; Douglas, M.E.; de Lange, T.; Lottersberger, F. DNA-PK controls Apollo’s access to leading-end telomeres. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 4313–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antosch, M.; Mortensen, S.A.; Grasser, K.D. Plant Proteins Containing High Mobility Group Box DNA-Binding Domains Modulate Different Nuclear Processes. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, T.; Broholm, S.; Becker, A. CRABS CLAW Acts as a Bifunctional Transcription Factor in Flower Development. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; Sawettalake, N.; Li, P.; Fan, S.; Shen, L. DNA methylation variations underlie lettuce domestication and divergence. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdev, S.; Biswas, R.; Roy, A.; Nandi, A.; Roy, V.; Basu, S.; Chaudhuri, S. The Arabidopsis ARID–HMG DNA-BINDING PROTEIN 15 modulates jasmonic acid signaling by regulating MYC2 during pollen development. Plant Physiol. 2024, 196, 996–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Chen, H.; Dang, J.; Shi, Z.; Shao, Y.; Liu, C.; Fan, L.; Wu, Q. Single-cell transcriptome of Nepeta tenuifolia leaves reveal differentiation trajectories in glandular trichomes. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 988594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chang, X.; Wang, X.; Li, G.; Chen, S.; Jin, S. Overexpression of LpCPC from Lilium pumilum confers saline-alkali stress (NaHCO3) resistance. Plant Signal. Behav. 2022, 17, e2057723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, R.; Prasad, P.; Kundu, A.; Sachdev, S.; Biswas, R.; Dutta, A.; Roy, A.; Mukhopadhyay, J.; Bag, S.K.; Chaudhuri, S. Identification of genome-wide targets and DNA recognition sequence of the Arabidopsis HMG-box protein AtHMGB15 during cold stress response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Gene Regul. Mech. 2020, 1863, 194644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villano, C.; D’Amelia, V.; Esposito, S.; Adelfi, M.G.; Contaldi, F.; Ferracane, R.; Vitaglione, P.; Aversano, R.; Carputo, D. Genome-Wide HMG Family Investigation and Its Role in Glycoalkaloid Accumulation in Wild Tuber-Bearing Solanum commersonii. Life 2020, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.X.; Li, S.S.; Yue, Q.Y.; Li, H.L.; Lu, J.; Li, W.C.; Wang, Y.N.; Liu, J.X.; Guo, X.L.; Wu, X.; et al. MdHMGB15-MdXERICO-MdNRP module mediates salt tolerance of apple by regulating the expression of salt stress-related genes. J. Adv. Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, C.; Feng, M.; Li, X.; Hou, Y.; Wei, C.; Zhang, X. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of Chitinase Genes in Watermelon under Abiotic Stimuli and Fusarium oxysporum Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.Z.; Ahmad, K.; Bashir Kutawa, A.; Siddiqui, Y.; Saad, N.; Geok Hun, T.; Hata, E.M.; Hossain, M.I. Biology, Diversity, Detection and Management of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum Causing Vascular Wilt Disease of Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus): A Review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, C.; Lan, G.; Si, F.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, C.; Yadav, V.; Wei, C.; Zhang, X. Systematic Genome-Wide Study and Expression Analysis of SWEET Gene Family: Sugar Transporter Family Contributes to Biotic and Abiotic Stimuli in Watermelon. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, E.S.; Black, K.; Feng, Z.; Liu, W.; Shan, N.; Zhang, X.; Wu, L.; Bailey, L.; Zhu, N.; Qi, C.; et al. Comprehensive Analysis of the Chitinase Gene Family in Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.): From Gene Identification and Evolution to Expression in Response to Fusarium oxysporum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Yan, Z.; Guan, J.; Huo, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, T.; Cui, Z.; Ma, W.; Wang, X.; Chen, W. Two interacting basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors control flowering time in rice. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, S.; Ntoukakis, V.; Ohmido, N.; Pendle, A.; Abranches, R.; Shaw, P. Cell Differentiation and Development in Arabidopsis Are Associated with Changes in Histone Dynamics at the Single-Cell Level. Plant Cell 2014, 26, 4821–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Name | Gene ID | Arabidopsis Ortholog Locus | E-Value | Genomic Sequence (bp) | CDS(bp) 1 | Protein Length (aa) | MW (kDa) 2 | pI 3 | Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ClHMGB1 | Cla97C01G008330.1 | AT5G23420.1/AtHMGB6 | 2.0 × 10−44 | 1822 (−) | 624 | 208 | 22.91 | 6.69 | N |

| ClHMGB2 | Cla97C01G024440.1 | AT2G34450.1/AtHMGB14 | 1.0 × 10−39 | 3011 (−) | 489 | 163 | 18.94 | 9.39 | N |

| ClHMGB3 | Cla97C04G073670.1 | AT3G51880.4/AtHMGB1 | 2 × 10−26 | 2496 (−) | 552 | 184 | 20.78 | 6.07 | N |

| ClHMGB4 | Cla97C05G096410.1 | AT1G76110.1/AtARID-HMG1 | 1.0 × 10−123 | 1604 (+) | 975 | 325 | 37.37 | 9.55 | N |

| ClHMGB5 | Cla97C06G117510.1 | AT1G04880.1/AtHMGB15 | 1.0 × 10−132 | 2909 (+) | 1497 | 499 | 55.92 | 4.88 | N |

| ClHMGB6 | Cla97C07G141850.1 | AT4G23800.2/At3xHMG-box2 | 1.0 × 10−113 | 2324 (+) | 1503 | 501 | 58.6 | 9.19 | N |

| ClHMGB7 | Cla97C10G184790.1 | AT1G20696.2/AtHMGB3 | 1.0 × 10−32 | 1073 (+) | 441 | 147 | 16.11 | 8.51 | N |

| ClHMGB8 | Cla97C10G197730.1 | AT3G28730.1/AtSSRP1 | 0 | 6714 (−) | 1929 | 643 | 71.61 | 5.73 | N |

| ClHMGB9 | Cla97C11G224900.1 | AT1G20693.3/AtHMGB2 | 2.0 × 10−44 | 1823 (+) | 663 | 221 | 23.93 | 9.08 | N |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xuan, C.; Yang, M.; Ma, Y.; Dai, X.; Liang, S.; Chang, G.; Zhang, X. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the ClHMGB Gene Family in Watermelon Under Abiotic Stress and Fusarium oxysporum Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010157

Xuan C, Yang M, Ma Y, Dai X, Liang S, Chang G, Zhang X. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the ClHMGB Gene Family in Watermelon Under Abiotic Stress and Fusarium oxysporum Infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010157

Chicago/Turabian StyleXuan, Changqing, Mengli Yang, Yufan Ma, Xue Dai, Shen Liang, Gaozheng Chang, and Xian Zhang. 2026. "Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the ClHMGB Gene Family in Watermelon Under Abiotic Stress and Fusarium oxysporum Infection" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010157

APA StyleXuan, C., Yang, M., Ma, Y., Dai, X., Liang, S., Chang, G., & Zhang, X. (2026). Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the ClHMGB Gene Family in Watermelon Under Abiotic Stress and Fusarium oxysporum Infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 157. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010157