Metabolic Profiling of Wheat Seedlings Under Oxygen Deficiency and Subsequent Reaeration Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

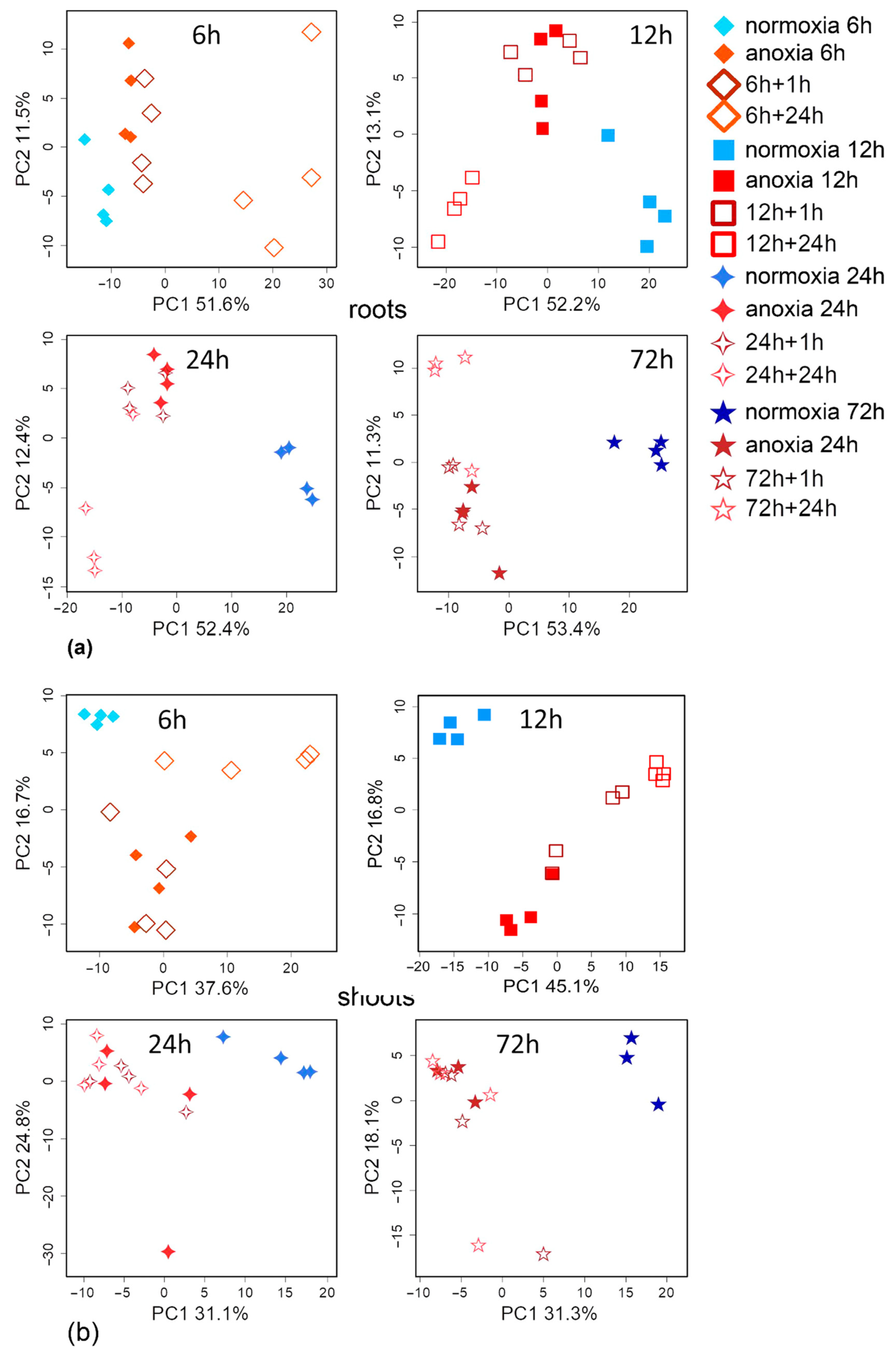

2.1. General Characteristics of Metabolic Profiles Under Anoxic Conditions

2.2. Metabolic Profiles Under Short-Term Anoxic Conditions (1–3 h)

2.3. Metabolic Profiles Under 6 h and Long-Term Anoxic Conditions (12–72 h)

2.3.1. Metabolic Profiles of Wheat Roots Under Long-Term Anoxic Conditions

2.3.2. Wheat Shoot Metabolic Profiles Under Long-Term Anoxic Conditions

2.4. Dynamics of Metabolites During Anoxia

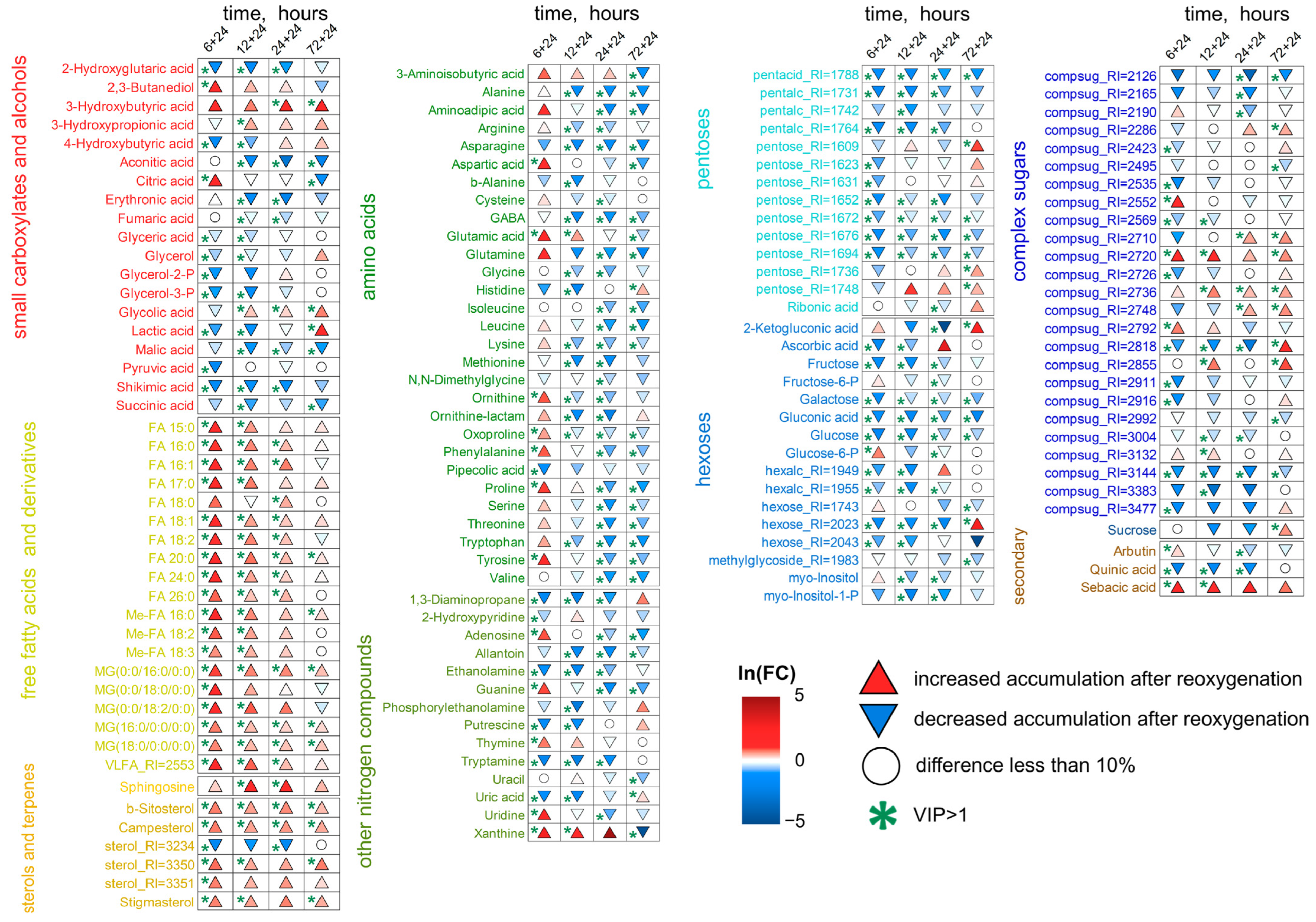

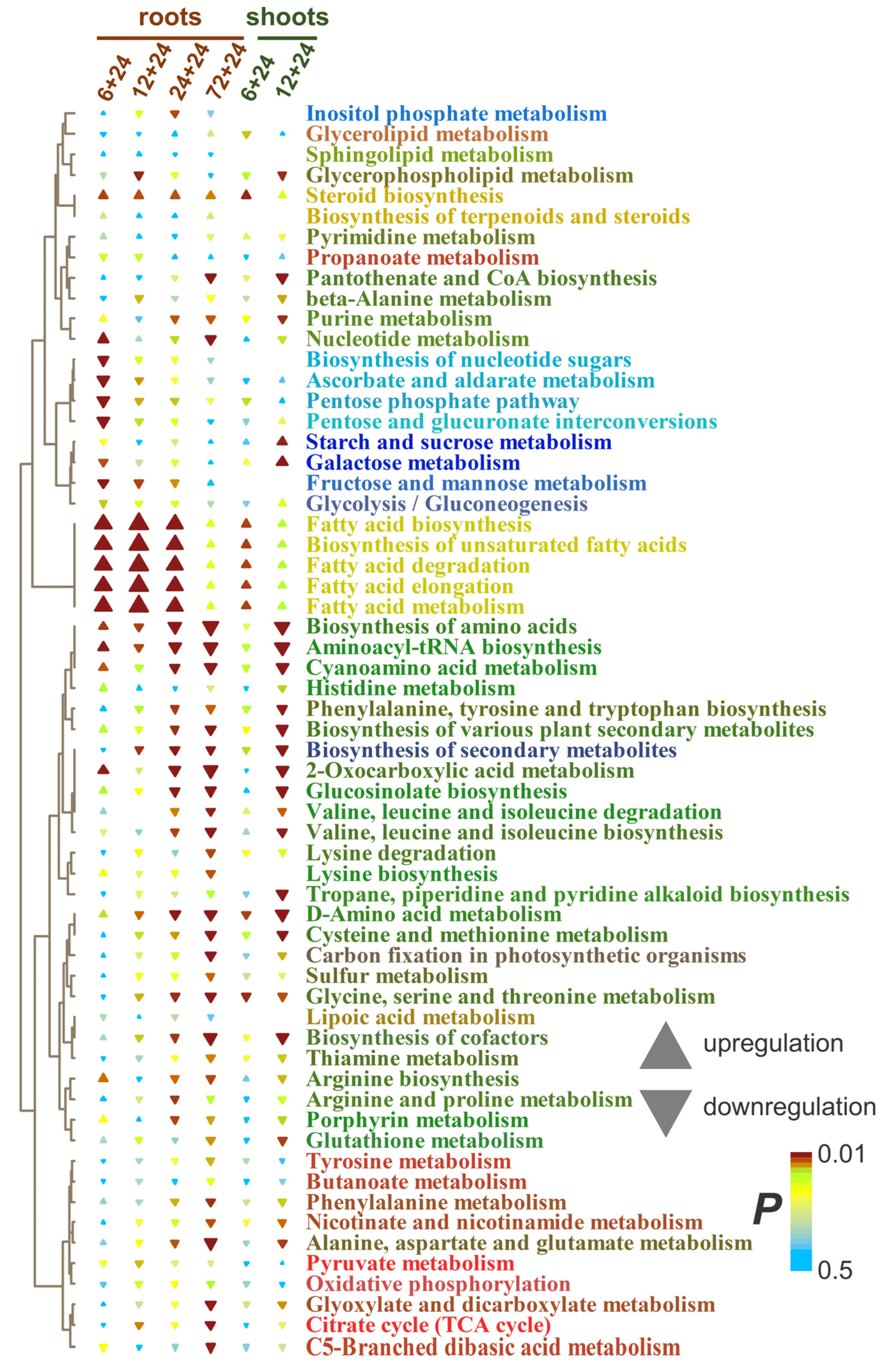

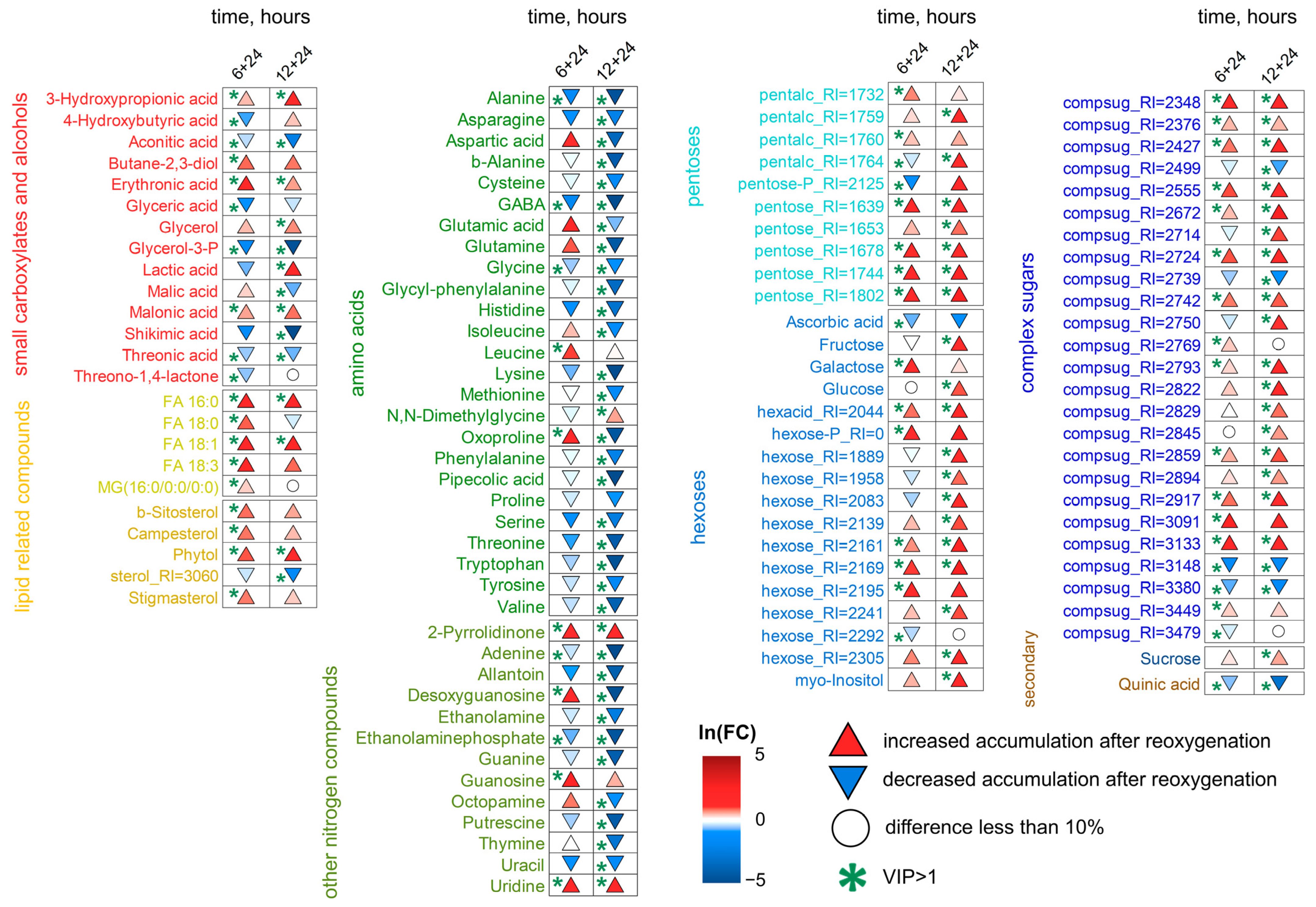

2.5. Wheat Metabolic Profiles Under Reoxygenation Conditions

3. Discussion

3.1. Metabolomes of Wheat Seedlings Under Short-Term Anoxic Conditions

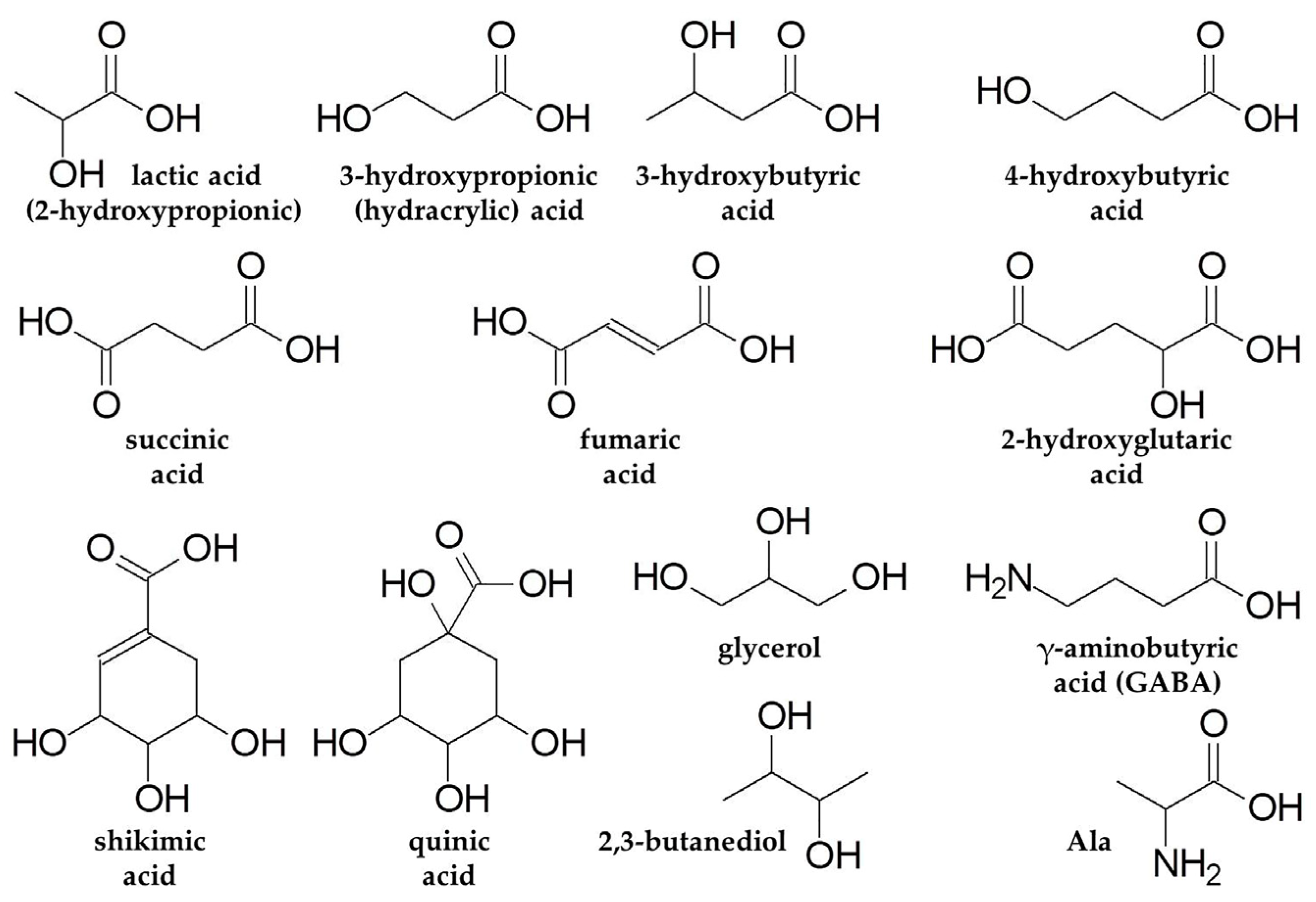

3.1.1. GABA Shunt

3.1.2. Hydroxyl Carboxylic Acids

3.2. Metabolomes of Wheat Seedlings Under Prolonged Anoxic Conditions

3.2.1. Carbohydrates

3.2.2. Amino Acids and Nucleotides

3.2.3. Carboxylic Acids

3.2.4. Lipids and Related Compounds

3.2.5. Main Directions of Metabolome Alterations

3.3. Wheat Metabolomes Under Reoxygenation Conditions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material, Growing Conditions and Imposition of Anoxia and Post-Anoxia

4.2. Sample Preparation for Metabolic Profiling

4.3. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

4.4. Interpretation of GC-MS Results

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GABA | γ-Aminobutyric Acid |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry |

| HCA | Hierarchical Cluster Analysis |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LOES | Low-Oxygen Escape Syndrome |

| LOQS | Low-Oxygen Quiescence Syndrome |

| MSEA | Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| OPLS-DA | Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures Discriminant Analysis |

| PC | Principal Component |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| RI | Retention Index |

| SUS | Shared and Unique Structure |

| VIP | Variable Importance in the Projection |

References

- Voesenek, L.A.C.J.; Bailey-Serres, J. Flood adaptive traits and processes: An overview. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirkova, T.; Yemelyanov, V. The study of plant adaptation to oxygen deficiency in Saint Petersburg University. Biol. Commun. 2018, 63, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukao, T.; Barrera-Figueroa, B.E.; Juntawong, P.; Peña-Castro, J.M. Submergence and waterlogging stress in plants: A review highlighting research opportunities and understudied aspects. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vartapetian, B.B.; Jackson, M.B. Plant adaptations to anaerobic stress. Ann. Bot. 1997, 79, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey-Serres, J.; Voesenek, L.A.C.J. Flooding stress: Acclimations and genetic diversity. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 313–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, B.G.; Fukao, T. Plant adaptation to multiple stresses during submergence and following desubmergence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 30164–30180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemelyanov, V.V.; Shishova, M.F. The role of phytohormones in the control of plant adaptation to oxygen depletion. In Phytohormones and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Plants; Khan, N.A., Nazar, R., Iqbal, N., Anjum, N.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kende, H.; van der Knaap, E.; Cho, H.-T. Deepwater rice: A model plant to study stem elongation. Plant Physiol. 1998, 118, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey-Serres, J.; Lee, S.C.; Brinton, E. Waterproofing crops: Effective flooding survival strategies. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 1698–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen, H.; Akman, M.; Jamar, D.C.L.; Vreugdenhil, D.; Kooiker, M.; van Tienderen, P.; Voesenek, L.A.C.J.; Schranz, M.E.; Sasidharan, R. Group VII Ethylene Response Factor diversification and regulation in four species from flood-prone environments. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 2421–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.B.; Bögemann, G.M.; van de Steeg, H.M.; Rijnders, J.G.H.M.; Voesenek, L.A.C.J.; Blom, C.W.P.M. Survival tactics of Ranunculus species in river floodplains. Oecologia 1999, 118, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, S.; Sasidharan, R.; Voesenek, L.A.C.J. The role of ethylene in metabolic acclimations to low oxygen. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey-Serres, J.; Fukao, T.; Gibbs, D.J.; Holdsworth, M.J.; Lee, S.C.; Licausi, F.; Perata, P.; Voesenek, L.A.C.J.; van Dongen, J.T. Making sense of low oxygen sensing. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreuzwieser, J.; Hauberg, J.; Howell, K.A.; Carroll, A.; Rennenberg, H.; Harvey Millar, A.; Whelan, J. Differential response of gray poplar leaves and roots underpins stress adaptation during hypoxia. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dongen, J.T.; Frohlich, A.; Ramirez-Aguilar, S.J.; Schauer, N.; Fernie, A.R.; Erban, A.; Kopka, J.; Clark, J.; Langer, A.; Geigenberger, P. Transcript and metabolite profiling of the adaptive response to mild decreases in oxygen concentration in the roots of arabidopsis plants. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shingaki-Wells, R.N.; Huang, S.; Taylor, N.L.; Carroll, A.J.; Zhou, W.; Harvey Millar, A. Differential molecular responses of rice and wheat coleoptiles to anoxia reveal novel metabolic adaptations in amino acid metabolism for tissue tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1706–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustroph, A.; Barding, G.A., Jr.; Kaiser, K.A.; Larive, C.K.; Bailey-Serres, J. Characterization of distinct root and shoot responses to low-oxygen stress in Arabidopsis with a focus on primary C- and N-metabolism. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 2366–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, A.M.; Barding, G.A., Jr.; Sathnur, S.; Larive, C.K.; Bailey-Serres, J. Rice SUB1A constrains remodelling of the transcriptome and metabolome during submergence to facilitate postsubmergence recovery. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, M.; Miyagi, A.; Kawai-Yamada, M.; Rashid, M.H.; Asaeda, T. Metabolic and biochemical responses of Potamogeton anguillanus Koidz. (Potamogetonaceae) to low oxygen conditions. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, 232, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yemelyanov, V.V.; Puzanskiy, R.K.; Bogdanova, E.M.; Vanisov, S.A.; Kirpichnikova, A.A.; Biktasheva, M.O.; Mukhina, Z.M.; Shavarda, A.L.; Shishova, M.F. Alterations in the rice coleoptile metabolome during elongation under submergence stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.; Licausi, F.; Araujo, W.L.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Sodek, L.; Fernie, A.R.; van Dongen, J.T. Glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid cycle are linked by alanine aminotransferase during hypoxia induced by waterlogging of Lotus japonicus. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1501–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- António, C.; Päpke, C.; Rocha, M.; Diab, H.; Limami, A.M.; Obata, T.; Fernie, A.R.; van Dongen, J.T. Regulation of primary metabolism in response to low oxygen availability as revealed by carbon and nitrogen isotope redistribution. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jethva, J.; Schmidt, R.R.; Sauter, M.; Selinski, J. Try or die: Dynamics of plant respiration and how to survive low oxygen conditions. Plants 2022, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Fu, X. Reprogramming of plant central metabolism in response to abiotic stresses: A metabolomics view. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemelyanov, V.V.; Puzanskiy, R.K.; Shishova, M.F. Plant life with and without oxygen: A metabolomics approach. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasler-Sheetal, H.; Fragner, L.; Holmer, M.; Weckwerth, W. Diurnal effects of anoxia on the metabolome of the seagrass Zostera marina. Metabolomics 2015, 11, 1208–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzanskiy, R.K.; Smirnov, P.D.; Vanisov, S.A.; Dubrovskiy, M.D.; Shavarda, A.L.; Shishova, M.F.; Yemelyanov, V.V. Metabolite profiling of leaves of three Epilobium species. Ecol. Genet. 2022, 20, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, P.D.; Puzanskiy, R.K.; Vanisov, S.A.; Dubrovskiy, M.D.; Shavarda, A.L.; Shishova, M.F.; Yemelyanov, V.V. Metabolic profiling of leaves of four Ranunculus species. Ecol. Genet. 2023, 21, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielminetti, L.; Yamaguchi, J.; Perata, P.; Alpi, A. Amylolytic activities in cereal seeds under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Plant Physiol. 1995, 109, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, M.; Fukao, T.; Winkel, A.; Konnerup, D.; Lamichhane, S.; Alpuerto, J.B.; Hasler-Sheetal, H.; Pedersen, O. Physiology, gene expression, and metabolome of two wheat cultivars with contrasting submergence tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 1632–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Shingaki-Wells, R.N.; Petereit, J.; Alexova, R.; Harvey Millar, A. Temperature-dependent metabolic adaptation of Triticum aestivum seedlings to anoxia. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallet, R.T.; Manukhina, E.B.; Ruelas, S.S.; Caffrey, J.L.; Downey, H.F. Cardioprotection by intermittent hypoxia conditioning: Evidence, mechanisms, and therapeutic potential. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2018, 315, H216–H232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikov, A.E.; Chirkova, T.V.; Yemelyanov, V.V. Post-anoxia in plants: Reasons, consequences, and possible mechanisms. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 67, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, J.; Castillo, M.C.; Gayubas, B. The hypoxia–reoxygenation stress in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 5841–5856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.I.; Colmer, T.D.; Lambers, H.; Setter, T.L.; Schortemeyer, M. Short-term waterlogging has long-term effects on the growth and physiology of wheat. New Phytol. 2002, 153, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, C.A.F.; Sodek, L. Alanine metabolism and alanine aminotransferase activity in soybean (Glycine max) during hypoxia of the root system and subsequent return to normoxia. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2003, 50, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelp, B.J.; Bown, A.W.; McLean, M.D. Metabolism and functions of gamma-aminobutyric acid. Trends Plant Sci. 1999, 4, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brikis, C.J.; Zarei, A.; Chiu, G.Z.; Deyman, K.L.; Liu, J.; Trobacher, C.P.; Hoover, G.J.; Subedi, S.; DeEll, J.R.; Bozzo, G.G.; et al. Targeted quantitative profiling of metabolites and gene transcripts associated with 4-aminobutyrate (GABA) in apple fruit stored under multiple abiotic stresses. Hortic. Res. 2018, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batushansky, A.; Kirma, M.; Grillich, N.; Toubiana, D.; Pham, P.A.; Balbo, I.; Fromm, H.; Galili, G.; Fernie, A.R.; Fait, A. Combined transcriptomics and metabolomics of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings exposed to exogenous GABA suggest its role in plants is predominantly metabolic. Mol. Plant. 2014, 7, 1065–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, W.L.; Simpson, J.P.; Clark, S.M.; Shelp, B.J. γ-Hydroxybutyrate accumulation in Arabidopsis and tobacco plants is a general response to abiotic stress: Putative regulation by redox balance and glyoxylate reductase isoforms. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 2555–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Ruiz, R.; Martinez, F.; Knauf-Beiter, G. The effects of GABA in plants. Cogent Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1670553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Dias, B.H.; Jung, S.-H.; Castro Oliveira, J.V.d.; Ryu, C.-M. C4 bacterial volatiles improve plant health. Pathogens 2021, 10, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaeli, S.; Fromm, H. Closing the loop on the GABA shunt in plants: Are GABA metabolism and signaling entwined? Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbaiah, C.; Bush, D.S.; Sachs, M. Elevation of cytosolic calcium precedes anoxic gene expression in maize suspension cultured cells. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 1747–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemelyanov, V.V.; Shishova, M.F.; Chirkova, T.V.; Lindberg, S.M. Anoxia-induced elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration depends on different Ca2+ sources in rice and wheat protoplasts. Planta 2011, 234, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah; Wani, K.I.; Naeem, M.; Aftab, T. From neurotransmitter to plant protector: The intricate world of GABA signaling and its diverse functions in stress mitigation. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, Y.; Pantazopoulou, C.K.; Prompers, J.J.; Pieterse, C.M.J.; Pol, H.H.; Kajala, K. Why did glutamate, GABA, and melatonin become intercellular signalling molecules in plants? eLife 2023, 12, e83361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramesh, S.; Tyerman, S.; Xu, B.; Bose, J.; Kaur, S.; Conn, V.; Domingos, P.; Ullah, S.; Wege, S.; Shabala, S.; et al. GABA signalling modulates plant growth by directly regulating the activity of plant-specific anion transporters. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beuve, N.; Rispail, N.; Laine, P.; Cliquet, J.-B.; Ourry, A.; Le Deunff, E. Putative role of γ -aminobutyric acid (GABA) as a long-distance signal in up-regulation of nitrate uptake in Brassica napus L. Plant Cell Environ. 2004, 27, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierziak, J.; Burgberger, M.; Wojtasik, W. 3-Hydroxybutyrate as a metabolite and a signal molecule regulating processes of living organisms. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schertl, P.; Danne, L.; Braun, H.P. 3-Hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase is involved in both, valine and isoleucine degradation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.S.; Broadbelt, L.J.; Hatzimanikatis, V. Discovery and analysis of novel metabolic pathways for the biosynthesis of industrial chemicals: 3-Hydroxypropanoate. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2010, 106, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xiang, S.; Zhao, G.; Wang, B.; Ma, Y.; Liu, W.; Tao, Y. Efficient production of 3-hydroxypropionate from fatty acids feedstock in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 2019, 51, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intlekofer, A.M.; Dematteo, R.G.; Venneti, S.; Finley, L.W.S.; Lu, C.; Judkins, A.R.; Rustenburg, A.S.; Grinaway, P.B.; Chodera, J.D.; Cross, J.R.; et al. Hypoxia induces production of L-2-hydroxyglutarate. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Hu, H. The roles of 2-hydroxyglutarate. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 651317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurino, V.G.; Engqvist, M.K.M. 2-Hydroxy acids in plant metabolism. Arab. Book 2015, 13, e0182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, M.V.; Pereira Júnior, A.A.; Medeiros, D.B.; Daloso, D.M.; Pham, P.A.; Barros, K.A.; Engqvist, M.K.M.; Florian, A.; Krahnert, I.; Maurino, V.G.; et al. The influence of alternative pathways of respiration that utilize branched-chain amino acids following water shortage in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1304–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brito, D.S.; Quinhones, C.G.S.; Neri-Silva, R.; Heinemann, B.; Schertl, P.; Cavalcanti, J.H.F.; Eubel, H.; Hildebrandt, T.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Braun, H.-P.; et al. The role of the electron-transfer flavoprotein: Ubiquinone oxidoreductase following carbohydrate starvation in Arabidopsis cell cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudig, M.; Maier, A.; Scherrers, I.; Seidel, L.; Jansen, E.E.W.; Mettler-Altmann, T.; Engqvist, M.K.M.; Maurino, V.G. Plants possess a cyclic mitochondrial metabolic pathway similar to the mammalian metabolic repair mechanism involving malate dehydrogenase and L-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 1820–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, G.A.; Francioli, D.; Kolb, S.; Tandron Moya, Y.A.; von Wirén, N.; Hajirezaei, M.R. Transcriptomic and metabolomic approaches elucidate the systemic response of wheat plants under waterlogging. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 1510–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T.J.; Reznick, J.; Peterson, B.L.; Blass, G.; Omerbašić, D.; Bennett, N.C.; Kuich, P.H.J.L.; Zasada, C.; Browe, B.M.; Hamann, W.; et al. Fructose-driven glycolysis supports anoxia resistance in the naked mole-rat. Science 2017, 356, 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peuke, A.D.; Gessler, A.; Trumbore, S.; Windt, C.W.; Homan, N.; Gerkema, E.; Van As, H. Phloem flow and sugar transport in Ricinus communis L. is inhibited under anoxic conditions of shoot or roots. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, T.E.; Smucker, A.J.M. Carbon transport and root respiration of split root systems of Phaseolus vulgaris subjected to short term localized anoxia. Plant Physiol. 1985, 78, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saglio, P.H. Effect of path or sink anoxia on sugar translocation in roots of maize seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1985, 77, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lothier, J.; Diab, H.; Cukier, C.; Limami, A.M.; Tcherkez, G. Metabolic responses to waterlogging differ between roots and shoots and reflect phloem transport alteration in Medicago truncatula. Plants 2020, 9, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig, J.G.; Ruilope, L.M. Uric acid as a cardiovascular risk factor in arterial hypertension. J. Hypertens. 1999, 17, 869–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magneschi, L.; Perata, P. Rice germination and seedling growth in the absence of oxygen. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matysik, J.; Alia Bhalu, B.; Mohanty, P. Molecular mechanisms of quenching of reactive oxygen species by proline under stress in plants. Curr. Sci. 2002, 82, 525–532. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, W.L.; Peiris, C.; Bown, A.W.; Shelp, B.J. Gamma-hydroxybutyrate accumulates in green tea and soybean sprouts in response to oxygen deficiency. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2003, 83, 951–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K.B.; Boldingh, H.L.; Shilton, R.S.; Laing, W.A. Changes in quinic acid metabolism during fruit development in three kiwifruit species. Funct. Plant Biol. 2009, 36, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weits, D.A.; van Dongen, J.; Francesco, L. Molecular oxygen as a signaling component in plant development. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkilä, E.; Hermant, A.; Thevenet, J.; Bermont, F.; Kulkarni, S.S.; Ratajczak, J.; Santo-Domingo, J.; Dioum, E.H.; Canto, C.; Barron, D.; et al. The plant product quinic acid activates Ca2+-dependent mitochondrial function and promotes insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 3250–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Q.F.; Xiao, S. New insights into the role of lipids in plant hypoxia responses. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021, 81, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.A.; Rumpho, M.E.; Fox, T.C. Anaerobic metabolism in plants. Plant Physiol. 1992, 100, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacek, L.; Dvorak, A.; Bechynska, K.; Kosek, V.; Elkalaf, M.; Trinh, M.D.; Fiserova, I.; Pospisilova, K.; Slovakova, L.; Vitek, L.; et al. Hypoxia induces saturated fatty acids accumulation and reduces unsaturated fatty acids independently of reverse tricarboxylic acid cycle in L6 myotubes. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 663625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brose, S.A.; Marquardt, A.L.; Golovko, M.Y. Fatty acid biosynthesis from glutamate and glutamine is specifically induced in neuronal cells under hypoxia. J. Neurochem. 2014, 129, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striesow, J.; Welle, M.; Busch, L.M.; Bekeschus, S.; Wende, K.; Stöhr, C. Hypoxia increases triacylglycerol levels and unsaturation in tomato roots. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini Tafreshi, A.; Shariati, M. Dunaliella biotechnology: Methods and applications. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahed, K.R.; Saini, A.K.; Sherif, S.M. Coping with the cold: Unveiling cryoprotectants, molecular signaling pathways, and strategies for cold stress resilience. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1246093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, W.; Zhang, L.; Cao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Kang, Z.; Guo, S.; Xu, P.; Ma, C.; et al. 2,3-Butanediol synthesis from glucose supplies NADH for elimination of toxic acetate produced during overflow metabolism. Cell Discov. 2021, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidnia, K.; Faghih-Mirzaei, E.; Miri, R.; Attarroshan, M.; Zomorodian, K. Biotransformation of acetoin to 2,3-butanediol: Assessment of plant and microbial biocatalysts. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 11, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.Y.; Ye, C.; Zhang, Y.J.; Zhang, J.X.; Yang, M.; He, X.H.; Mei, X.Y.; Liu, Y.X.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Huang, H.C.; et al. 2,3-Butanediol from the leachates of pine needles induces the resistance of Panax notoginseng to the leaf pathogen Alternaria panax. Plant Divers. 2022, 45, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, H.G.; Shin, T.S.; Kim, T.H.; Ryu, C.-M. Stereoisomers of the bacterial volatile compound 2,3-butanediol differently elicit systemic defense responses of pepper against multiple viruses in the field. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranea-Robles, P.; Houten, S.M. The biochemistry and physiology of long-chain dicarboxylic acid metabolism. Biochem. J. 2023, 480, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Sala, P.; Peña-Quintana, L. Biochemical markers for the diagnosis of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanath, S.J.; Delude, C.; Domergue, F.; Rowland, O. Suberin: Biosynthesis, regulation, and polymer assembly of a protective extracellular barrier. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Wu, Q.; Jin, S.; Liu, J.; Qin, M.; Deng, L.; Wang, F. Biocatalytic cascade of sebacic acid production with in situ co-factor regeneration enabled by engineering of an alcohol dehydrogenase. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, D.; de la Fuente, A.; Mendes, P. The origin of correlations in metabolomics data. Metabolomics 2005, 1, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuer, R. Review: On the analysis and interpretation of correlations in metabolomic data. Brief Bioinform. 2006, 7, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yemelyanov, V.V.; Lastochkin, V.V.; Chirkova, T.V.; Lindberg, S.M.; Shishova, M.F. Indoleacetic acid levels in wheat and rice seedlings under oxygen deficiency and subsequent reoxygenation. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManmon, M.; Crawford, R.M.M. A metabolic theory of flooding tolerance: The significance of enzyme distribution and behavior. New Phytol. 1971, 70, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menegus, F.; Cattaruzza, L.; Chersi, A.; Fronza, G. Differences in the anaerobic lactate-succinate production and in the changes of cell sap pH for plants with high and low resistance to anoxia. Plant Physiol. 1989, 90, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, R.M.M. Oxygen availability as an ecological limit to plant distribution. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1992, 23, 93–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikov, A.E.; Shost, V.I.; Chirkova, T.V.; Shishova, M.F.; Yemelyanov, V.V. Forewarned is forearmed: Rice plants develop tolerance to post-anoxia during anoxic conditions by proteomic changes. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1647411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yemelyanov, V.V.; Prikaziuk, E.G.; Lastochkin, V.V.; Aresheva, O.M.; Chirkova, T.V. Ascorbate-glutathione cycle in wheat and rice seedlings under anoxia and subsequent reaeration. Vavilov J. Genet. Breed. 2024, 28, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirkova, T.V.; Novitskaya, L.O.; Blokhina, O.B. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant systems under anoxia in plants differing in their tolerance to oxygen deficiency. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 1998, 45, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Blokhina, O.B.; Fagerstedt, K.V.; Chirkova, T.V. Relationships between lipid peroxidation and anoxia tolerance in a range of species during post-anoxic reaeration. Physiol. Plant 1999, 105, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikov, A.E.; Lastochkin, V.V.; Chirkova, T.V.; Mukhina, Z.M.; Yemelyanov, V.V. Post-anoxic oxidative injury is more severe than oxidative stress induced by chemical agents in wheat and rice plants. Acta Physiol. Plant 2022, 44, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Xu, Y. Dynamic metabolic changes in arabidopsis seedlings under hypoxia stress and subsequent reoxygenation recovery. Stresses 2023, 3, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.-J.; Lin, C.-Y.; Ting, C.-Y.; Shih, M.-C. Ethylene-regulated glutamate dehydrogenase fine-tunes metabolism during anoxia-reoxygenation. Plant Physiol. 2016, 172, 1548–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emel’yanov, V.V.; Kirchikhina, N.A.; Lastochkin, V.V.; Chirkova, T.V. Hormonal balance of wheat and rice seedlings under anoxia. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 50, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzanskiy, R.K.; Yemelyanov, V.V.; Kliukova, M.S.; Shavarda, A.L.; Shtark, O.Y.; Yurkov, A.P.; Shishova, M.F. Optimization of metabolite profiling for black medick (Medicago lupulina) and peas (Pisum sativum). Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2018, 54, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, L.G.; Skou, P.B.; Khakimov, B.; Bro, R. Gas chromatography—Mass spectrometry data processing made easy. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1503, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, J.; Selbig, J.; Walther, D.; Kopka, J. The Golm Metabolome Database: A Database for GC-MS based metabolite profiling. In Metabolomics. Topics in Current Genetics; Nielsen, J., Jewett, M.C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 18, pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Komsta, L. Outliers: Tests for Outliers. R Package Version 0.15. 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=outliers (accessed on 1 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Narasimhan, B.; Chu, G. impute: Impute: Imputation for Microarray Data. R Package Version 1.70.0. 2022. Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/impute.html (accessed on 1 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Stacklies, W.; Redestig, H.; Scholz, M.; Walther, D.; Selbig, J. pcaMethods—A Bioconductor package providing PCA methods for incomplete data. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 1164–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevenot, E.A.; Roux, A.; Xu, Y.; Ezan, E.; Junot, C. Analysis of the human adult urinary metabolome variations with age, body mass index and gender by implementing a comprehensive workflow for univariate and OPLS statistical analyses. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 3322–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brereton, R.G.; Lloyd, G.R. Partial least squares discriminant analysis: Taking the magic away. J. Chemom. 2013, 28, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Eils, R.; Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2847–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korotkevich, G.; Sukhov, V.; Sergushichev, A. Fast gene set enrichment analysis. bioRxiv 2019, 060012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenbaum, D.; Maintainer, B. KEGGREST: Client-Side REST Access to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). 2022. R package Version 1.36.2. Available online: https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/KEGGREST.html (accessed on 1 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yemelyanov, V.V.; Puzanskiy, R.K.; Bogdanova, E.M.; Vanisov, S.A.; Dubrovskiy, M.D.; Lastochkin, V.V.; Kirpichnikova, A.A.; Brykova, A.N.; Shavarda, A.L.; Shishova, M.F. Metabolic Profiling of Wheat Seedlings Under Oxygen Deficiency and Subsequent Reaeration Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311610

Yemelyanov VV, Puzanskiy RK, Bogdanova EM, Vanisov SA, Dubrovskiy MD, Lastochkin VV, Kirpichnikova AA, Brykova AN, Shavarda AL, Shishova MF. Metabolic Profiling of Wheat Seedlings Under Oxygen Deficiency and Subsequent Reaeration Conditions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311610

Chicago/Turabian StyleYemelyanov, Vladislav V., Roman K. Puzanskiy, Ekaterina M. Bogdanova, Sergey A. Vanisov, Maksim D. Dubrovskiy, Victor V. Lastochkin, Anastasia A. Kirpichnikova, Alla N. Brykova, Alexey L. Shavarda, and Maria F. Shishova. 2025. "Metabolic Profiling of Wheat Seedlings Under Oxygen Deficiency and Subsequent Reaeration Conditions" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311610

APA StyleYemelyanov, V. V., Puzanskiy, R. K., Bogdanova, E. M., Vanisov, S. A., Dubrovskiy, M. D., Lastochkin, V. V., Kirpichnikova, A. A., Brykova, A. N., Shavarda, A. L., & Shishova, M. F. (2025). Metabolic Profiling of Wheat Seedlings Under Oxygen Deficiency and Subsequent Reaeration Conditions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11610. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311610