Integrative Multi-Omics and Machine Learning Reveal Shared Biomarkers in Type 2 Diabetes and Atherosclerosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. WGCNA Identifies Trait-Related Modules

2.2. Identification of DEGs in T2DM and AS

2.3. T2DM–AS DEGs and Functional Enrichment

2.4. PPI Network and Hub-Gene Analysis

2.5. Machine-Learning Identification and Validation of T2DM–AS Hub DEGs

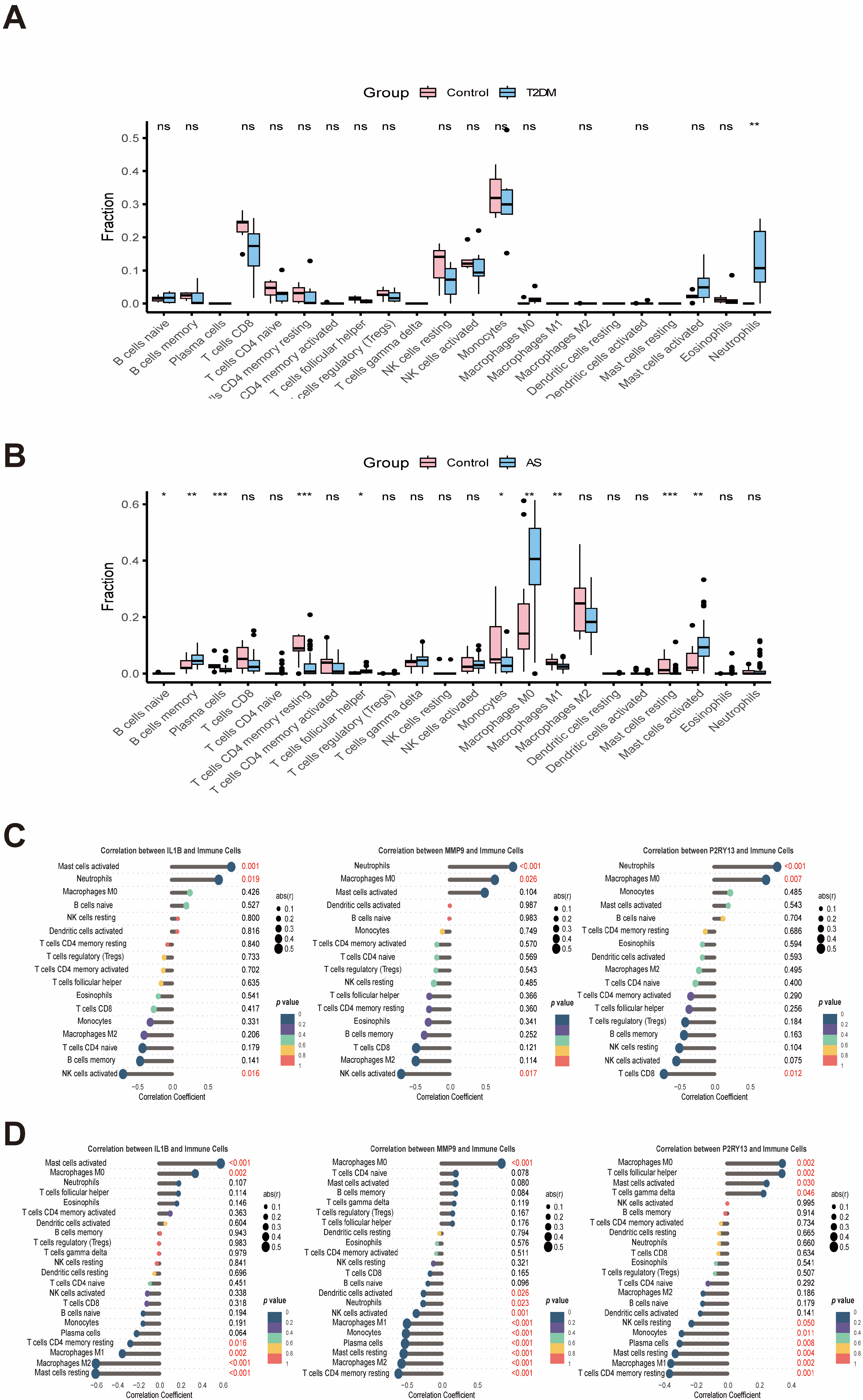

2.6. Immune Infiltration and Single-Cell Results

2.7. Evaluating the Expression of the Candidate Genes in the HAEC-SV40 Cell Line

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Sources

4.2. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

4.3. Identification of DEGs

4.4. Functional Enrichment Analysis

4.5. PPI Network Analysis

4.6. Machine Learning and Clinical-Feature Analysis

4.7. Immune Infiltration and Single-Cell Analyses

4.8. Cell Culture and Treatment

4.9. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| AS | Atherosclerosis |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| WGCNA | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LASSO | Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator |

| RF | Random forest |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| IL1B | Interleukin 1, beta |

| MMP9 | Matrix metallopeptidase 9 |

| P2RY13 | Purinergic receptor P2Y, G-protein coupled, 13 |

| OOB | Out-of-bag |

| CV | Cross-validation |

References

- Ong, K.L.; Stafford, L.K.; McLaughlin, S.A.; Boyko, E.J.; Vollset, S.E.; Smith, A.E.; Dalton, B.E.; Duprey, J.; Cruz, J.A.; Hagins, H.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with Projections of Prevalence to 2050: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2023, 402, 203–234, Correction in Lancet 2023, 402, 1132. Correction in Lancet 2025, 405, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinajero, M.G.; Malik, V.S. An Update on the Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes: A Global Perspective. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 50, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avogaro, A.; Fadini, G.P. Microvascular Complications in Diabetes: A Growing Concern for Cardiologists. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 291, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, S.; Nawroth, P.P.; Herzig, S.; Ekim Üstünel, B. Emerging Targets in Type 2 Diabetes and Diabetic Complications. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2100275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, E. Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, C7–C12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Differences in Carotid Plaques Between Symptomatic Patients with and Without Diabetes Mellitus. Available online: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/epub/10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.312092 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Patsouras, A.; Farmaki, P.; Garmpi, A.; Damaskos, C.; Garmpis, N.; Mantas, D.; Diamantis, E. Screening and Risk Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: An Updated Review. In Vivo 2019, 33, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplovitch, E.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Dyal, L.; Aboyans, V.; Abola, M.T.; Verhamme, P.; Avezum, A.; Fox, K.A.A.; Berkowitz, S.D.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; et al. Rivaroxaban and Aspirin in Patients with Symptomatic Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Gao, M.; Wang, W.; Chen, K.; Huang, L.; Liu, Y. Diabetic Vascular Diseases: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffia, P.; Mauro, C.; Case, A.; Kemper, C. Canonical and Non-Canonical Roles of Complement in Atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2024, 21, 743–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poznyak, A.V.; Grechko, A.V.; Orekhova, V.A.; Khotina, V.; Ivanova, E.A.; Orekhov, A.N. NADPH Oxidases and Their Role in Atherosclerosis. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, C.J.; Drazen, J.M. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Clinical Medicine, 2023. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 1201–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinarello, C.A.; Donath, M.Y.; Mandrup-Poulsen, T. Role of IL-1β in Type 2 Diabetes. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2010, 17, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peiró, C.; Lorenzo, Ó.; Carraro, R.; Sánchez-Ferrer, C.F. IL-1β Inhibition in Cardiovascular Complications Associated to Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikama, Y.; Aki, N.; Hata, A.; Nishimura, M.; Oyadomari, S.; Funaki, M. Palmitate-Stimulated Monocytes Induce Adhesion Molecule Expression in Endothelial Cells via IL-1 Signaling Pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2015, 230, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Everett, B.M.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Thuren, T.; Libby, P.; Glynn, R.J.; Ridker, P.M. Inhibition of Interleukin-1β and Reduction in Atherothrombotic Cardiovascular Events in the CANTOS Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 1660–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinarello, C.A. A Clinical Perspective of IL-1β as the Gatekeeper of Inflammation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011, 41, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.; Subramanian, M. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) as Drivers of Atherosclerosis: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 274, 108917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, W.; Liao, Y. Targeting IL-1β in the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 589654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijdan, S.A.; Bokhari, S.M.N.A.; Alvares, J.; Latif, V. The Role of Interleukin-1 Beta in Inflammation and the Potential of Immune-Targeted Therapies. Pharmacol. Res.—Rep. 2025, 3, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.; Patel, A.P.; Debs, L.H.; Nguyen, D.; Patel, K.; Grati, M.; Mittal, J.; Yan, D.; Chapagain, P.; Liu, X.Z. Intricate Functions of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016, 231, 2599–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Khalil, R.A. Matrix Metalloproteinases, Vascular Remodeling, and Vascular Disease. Adv. Pharmacol. 2018, 81, 241–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Kim, S.H.; Monticone, R.E.; Lakatta, E.G. Matrix Metalloproteinases Promote Arterial Remodeling in Aging, Hypertension, and Atherosclerosis. Hypertension 2015, 65, 698–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wågsäter, D.; Zhu, C.; Björkegren, J.; Skogsberg, J.; Eriksson, P. MMP-2 and MMP-9 Are Prominent Matrix Metalloproteinases during Atherosclerosis Development in the Ldlr-/-Apob100/100 Mouse. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2011, 28, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandour, F.; Kassem, S.; Simanovich, E.; Rahat, M.A. Glucose Promotes EMMPRIN/CD147 and the Secretion of Pro-Angiogenic Factors in a Co-Culture System of Endothelial Cells and Monocytes. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Su, L.; Loo, S.J.; Gao, Y.; Khin, E.; Kong, X.; Dalan, R.; Su, X.; Lee, K.-O.; Ma, J.; et al. Matrix Metallopeptidase 9 Contributes to the Beginning of Plaque and Is a Potential Biomarker for the Early Identification of Atherosclerosis in Asymptomatic Patients with Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1369369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buraczynska, M.; Wrzos, S.; Zaluska, W. MMP9 Gene Polymorphism (Rs3918242) Increases the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Type 2 Diabetes Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blankenberg, S.; Rupprecht, H.J.; Poirier, O.; Bickel, C.; Smieja, M.; Hafner, G.; Meyer, J.; Cambien, F.; Tiret, L. Plasma Concentrations and Genetic Variation of Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 and Prognosis of Patients With Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2003, 107, 1579–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, E.M.; Pearce, S.W.A.; Xiao, R.; Oo, A.Y.; Xiao, Q. Matrix Metalloproteinase in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm and Aortic Dissection. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Hussien, H.; Hanemaaijer, R.; Verheijen, J.H.; van Bockel, J.H.; Geelkerken, R.H.; Lindeman, J.H.N. Doxycycline Therapy for Abdominal Aneurysm: Improved Proteolytic Balance through Reduced Neutrophil Content. J. Vasc. Surg. 2009, 49, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sen, R.; Gómez-Villafuertes, R.; Ortega, F.; Gualix, J.; Delicado, E.G.; Miras-Portugal, M.T. An Update on P2Y13 Receptor Signalling and Function. In Protein Reviews; Atassi, M.Z., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; Volume 19, pp. 139–168. ISBN 978-981-10-7611-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Wei, S.; Chen, M.; Li, J.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, J.; Dong, W. P2RY13 Exacerbates Intestinal Inflammation by Damaging the Intestinal Mucosal Barrier via Activating IL-6/STAT3 Pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 5056–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Yang, X.; Li, H.; Li, C.; Li, C.; Chen, C.; Ye, S.; Zou, L.; Liang, S.; Liu, S. P2Y13 Receptor Involved in HIV-1 Gp120 Induced Neuropathy in Superior Cervical Ganglia through NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Neuropharmacology 2024, 245, 109818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werder, R.B.; Ullah, M.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Simpson, J.; Lynch, J.P.; Collinson, N.; Rittchen, S.; Rashid, R.B.; Sikder, M.A.A.; Handoko, H.Y.; et al. Targeting the P2Y13 Receptor Suppresses IL-33 and HMGB1 Release and Ameliorates Experimental Asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duparc, T.; Gore, E.; Combes, G.; Beuzelin, D.; Pires Da Silva, J.; Bouguetoch, V.; Marquès, M.-A.; Velazquez, A.; Viguerie, N.; Tavernier, G.; et al. P2Y13 Receptor Deficiency Favors Adipose Tissue Lipolysis and Worsens Insulin Resistance and Fatty Liver Disease. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e175623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabre, A.C.; Malaval, C.; Ben Addi, A.; Verdier, C.; Pons, V.; Serhan, N.; Lichtenstein, L.; Combes, G.; Huby, T.; Briand, F.; et al. P2Y13 Receptor Is Critical for Reverse Cholesterol Transport. Hepatology 2010, 52, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenstein, L.; Serhan, N.; Annema, W.; Combes, G.; Robaye, B.; Boeynaems, J.-M.; Perret, B.; Tietge, U.J.F.; Laffargue, M.; Martinez, L.O. Lack of P2Y13 in Mice Fed a High Cholesterol Diet Results in Decreased Hepatic Cholesterol Content, Biliary Lipid Secretion and Reverse Cholesterol Transport. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, L.; Serhan, N.; Espinosa-Delgado, S.; Fabre, A.; Annema, W.; Tietge, U.J.F.; Robaye, B.; Boeynaems, J.-M.; Laffargue, M.; Perret, B.; et al. Increased Atherosclerosis in P2Y13/Apolipoprotein E Double-Knockout Mice: Contribution of P2Y13 to Reverse Cholesterol Transport. Cardiovasc. Res. 2015, 106, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pons, V.; Serhan, N.; Gayral, S.; Malaval, C.; Nauze, M.; Malet, N.; Laffargue, M.; Galés, C.; Martinez, L.O. Role of the Ubiquitin–Proteasome System in the Regulation of P2Y13 Receptor Expression: Impact on Hepatic HDL Uptake. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 71, 1775–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, T.; Collado, A.; Mahdi, A.; Jurga, J.; Tengbom, J.; Saleh, N.; Verouhis, D.; Böhm, F.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, J.; et al. Erythrocytes from Patients with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Induce Cardioprotection through the Purinergic P2Y13 Receptor and Nitric Oxide Signaling. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2022, 117, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafuse, W.P.; Wozniak, D.J.; Rajaram, M.V.S. Role of Cardiac Macrophages on Cardiac Inflammation, Fibrosis and Tissue Repair. Cells 2020, 10, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, N.; Ebrahimian, T.; Gloaguen, C.; Kereselidze, D.; Christelle, E.; Brizais, C.; Bachelot, F.; Riazi, G.; Monceau, V.; Demarquay, C.; et al. Low to Moderate Dose 137Cs (γ) Radiation Promotes M2 Type Macrophage Skewing and Reduces Atherosclerotic Plaque CD68+ Cell Content in ApoE(−/−) Mice. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khallou-Laschet, J.; Varthaman, A.; Fornasa, G.; Compain, C.; Gaston, A.-T.; Clement, M.; Dussiot, M.; Levillain, O.; Graff-Dubois, S.; Nicoletti, A.; et al. Macrophage Plasticity in Experimental Atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Zhou, W.-H.; Cai, J.-J.; Feng, M.; Zhou, M.; Hu, S.-P.; Xu, J.; Ji, L.-D. Gene Expression Profiling Identifies Downregulation of the Neurotrophin-MAPK Signaling Pathway in Female Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy Patients. J. Diabetes Res. 2017, 2017, 8103904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenman, M.; Espitia, O.; Maurel, B.; Guyomarch, B.; Heymann, M.-F.; Pistorius, M.-A.; Ory, B.; Heymann, D.; Houlgatte, R.; Gouëffic, Y.; et al. Identification of Genomic Differences among Peripheral Arterial Beds in Atherosclerotic and Healthy Arteries. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Y.; Xiong, S.; Li, L.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, W.; Cai, H.; Feng, G.; Wang, X.; Yao, H.; et al. Spatial Multiomics Atlas Reveals Smooth Muscle Phenotypic Transformation and Metabolic Reprogramming in Diabetic Macroangiopathy. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | Description | MCC | MNC | Degree | EPC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALOX5 | arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase | 5880 | 9 | 9 | 19.533 |

| ALOX5AP | arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein | 10,114 | 11 | 11 | 20.409 |

| AQP9 | aquaporin 9 | 1664 | 12 | 12 | 20.771 |

| C3AR1 | complement component 3a receptor 1 | 422 | 12 | 12 | 20.26 |

| CSF3R | colony-stimulating factor 3 receptor (granulocyte) | 7514 | 14 | 16 | 22.092 |

| CXCL1 | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (melanoma growth-stimulating activity, alpha) | 262 | 11 | 11 | 19.792 |

| FGR | FGR proto-oncogene, Src family tyrosine kinase | 11,741 | 16 | 17 | 21.855 |

| FPR1 | formyl peptide receptor 1 | 13,618 | 18 | 18 | 22.985 |

| IGSF6 | immunoglobulin superfamily, member 6 | 104 | 9 | 9 | 18.533 |

| IL1B | interleukin 1, beta | 13,641 | 24 | 25 | 22.966 |

| MMP9 | matrix metallopeptidase 9 | 1614 | 15 | 15 | 21.094 |

| MYO1F | myosin IF | 29 | 6 | 7 | 15.35 |

| NCF2 | neutrophil cytosolic factor 2 | 12,754 | 16 | 16 | 22.511 |

| NCF4 | neutrophil cytosolic factor 4, 40kDa | 11,575 | 12 | 13 | 21.048 |

| P2RY13 | purinergic receptor P2Y, G-protein coupled, 13 | 33 | 6 | 7 | 16.029 |

| PTAFR | platelet-activating factor receptor | 151 | 9 | 10 | 19.155 |

| SLC11A1 | solute carrier family 11 (proton-coupled divalent metal ion transporter), member 1 | 722 | 7 | 7 | 17.813 |

| TLR2 | toll-like receptor 2 | 13,724 | 22 | 22 | 22.831 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Fan, M.; Hao, L.; Chen, J.; Wu, C.; Gao, B. Integrative Multi-Omics and Machine Learning Reveal Shared Biomarkers in Type 2 Diabetes and Atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010136

Wu Q, Wang Z, Fan M, Hao L, Chen J, Wu C, Gao B. Integrative Multi-Omics and Machine Learning Reveal Shared Biomarkers in Type 2 Diabetes and Atherosclerosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010136

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Qingjie, Zhaochu Wang, Mengzhen Fan, Linglun Hao, Jicheng Chen, Changwen Wu, and Bizhen Gao. 2026. "Integrative Multi-Omics and Machine Learning Reveal Shared Biomarkers in Type 2 Diabetes and Atherosclerosis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010136

APA StyleWu, Q., Wang, Z., Fan, M., Hao, L., Chen, J., Wu, C., & Gao, B. (2026). Integrative Multi-Omics and Machine Learning Reveal Shared Biomarkers in Type 2 Diabetes and Atherosclerosis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010136