Characteristics and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Complete Chloroplast Genome of Abelmoschus esculentus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

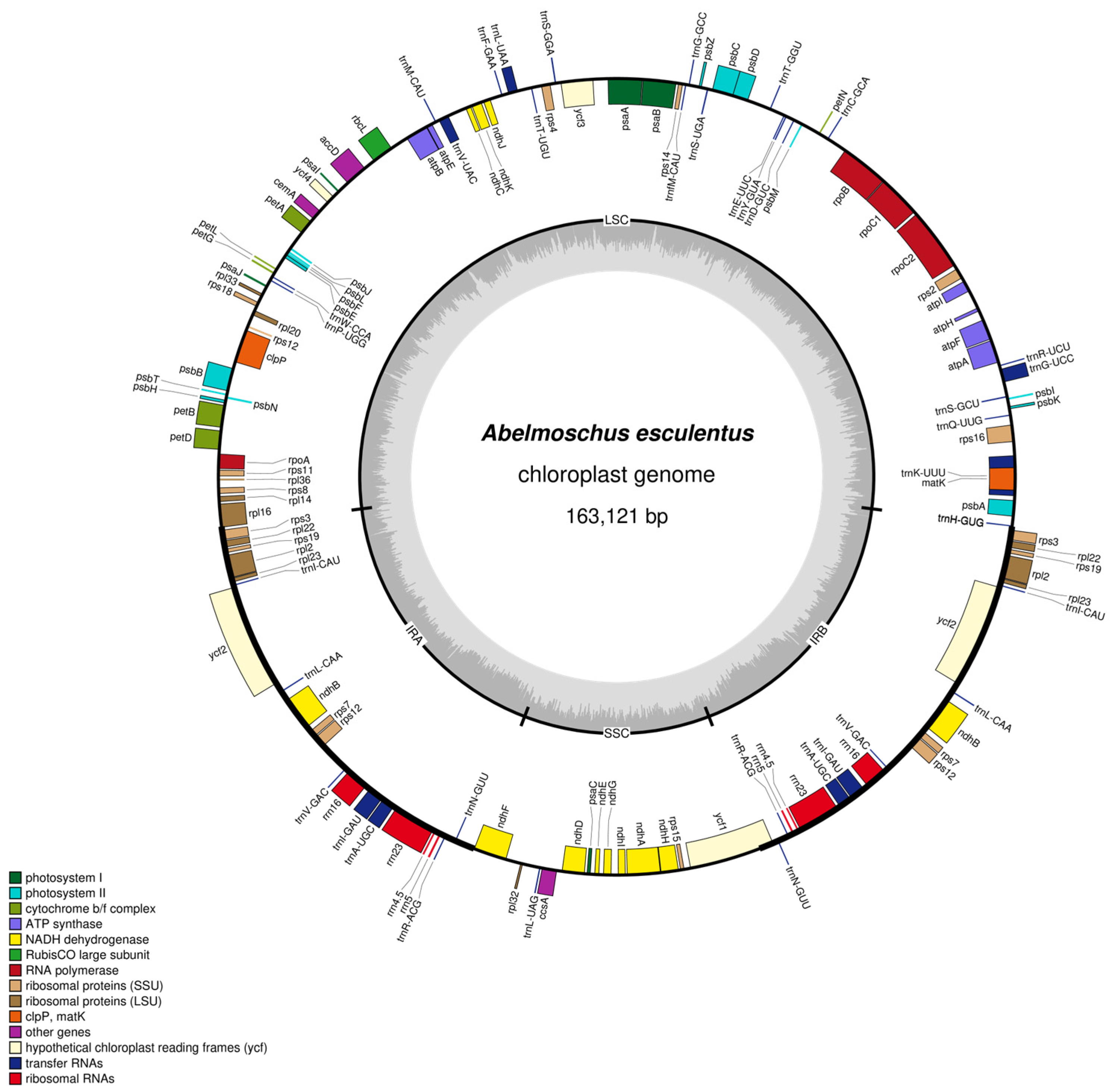

2.1. Basic Characteristics of the Chloroplast Genome of Abelmoschus esculentus

2.2. Functional Annotation of Chloroplast Genes

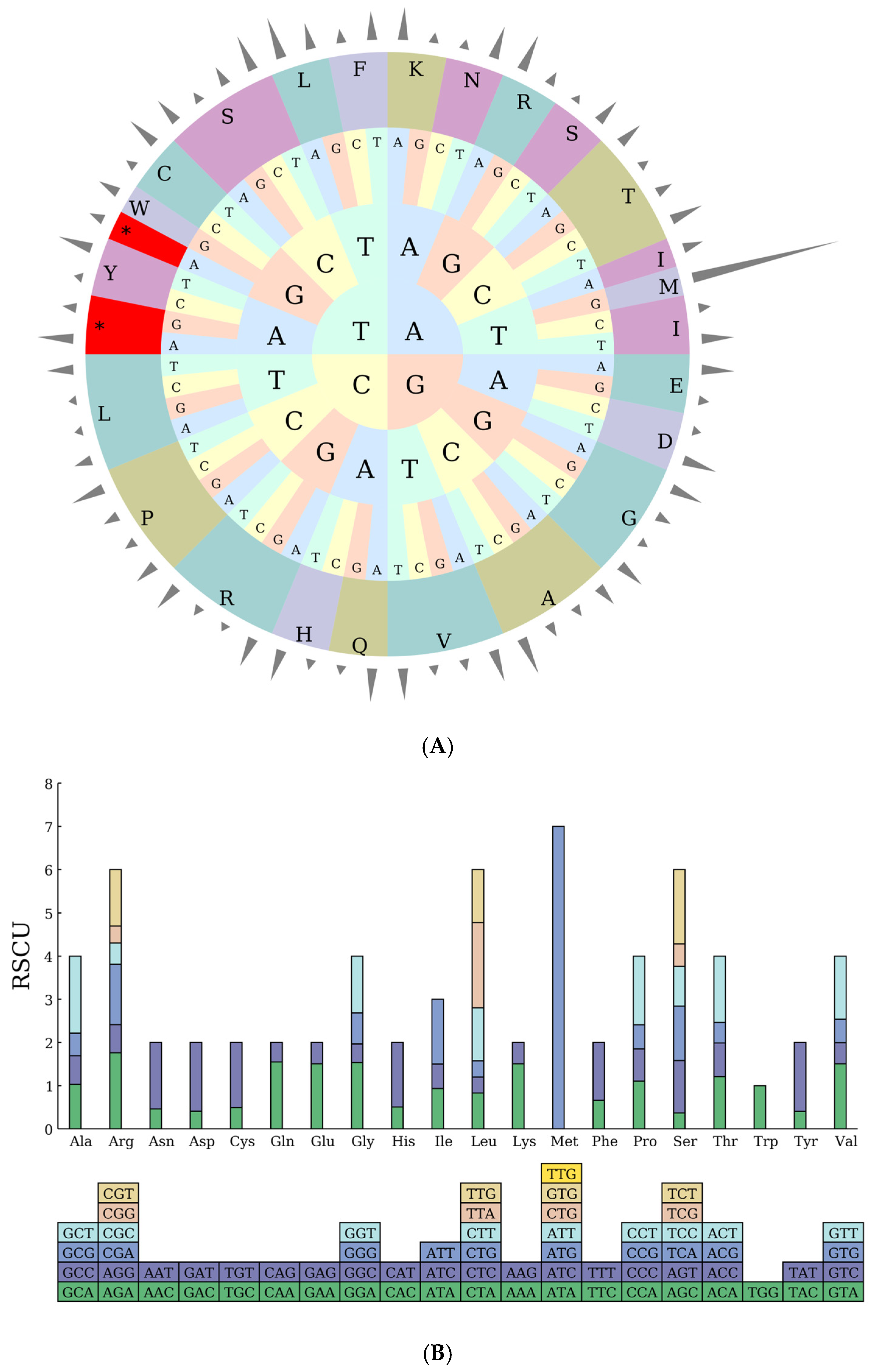

2.3. Codon Preference Analysis

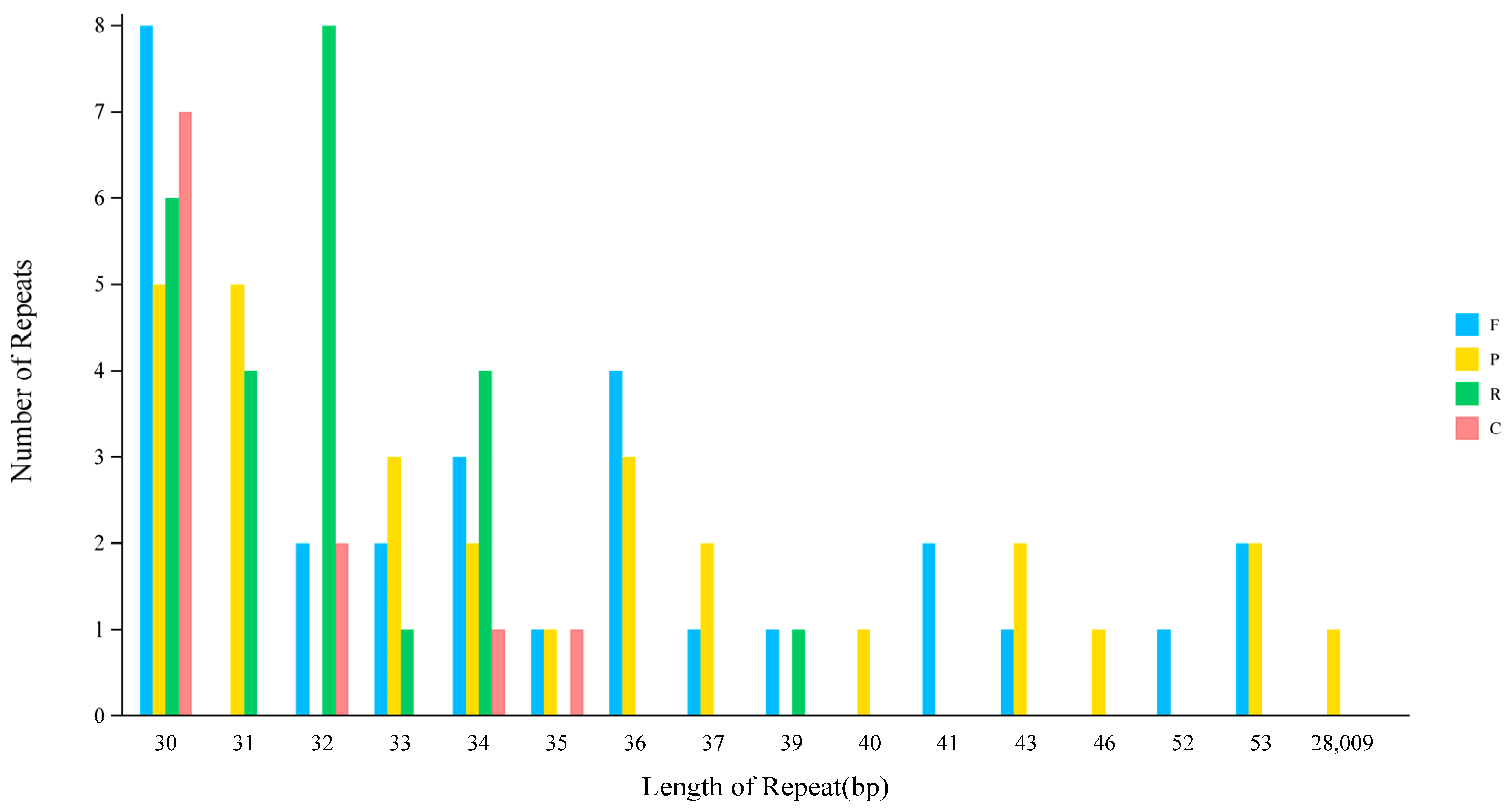

2.4. Repeat Sequence Analysis

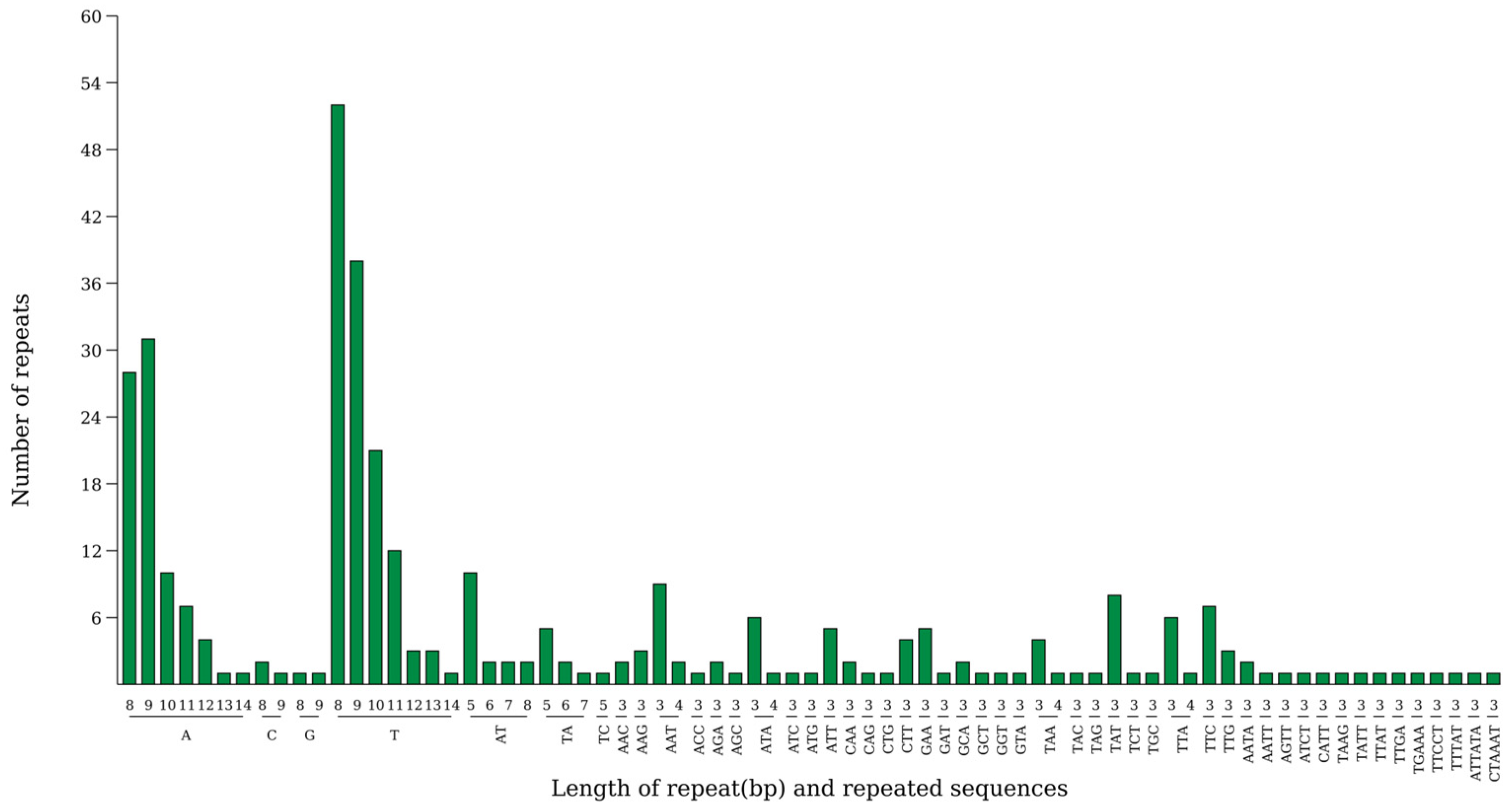

2.5. Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) Analysis

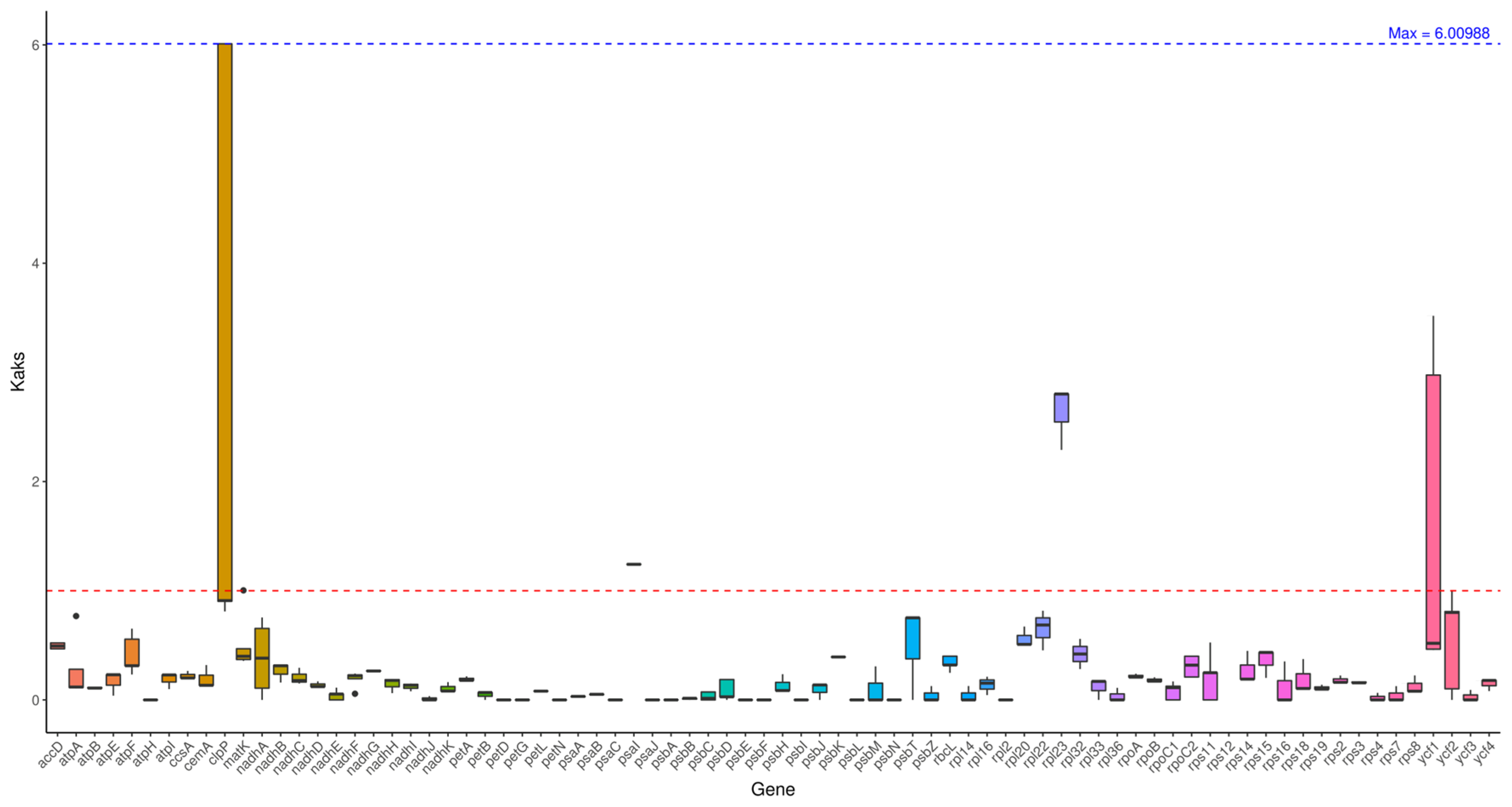

2.6. Ka/Ks Analysis

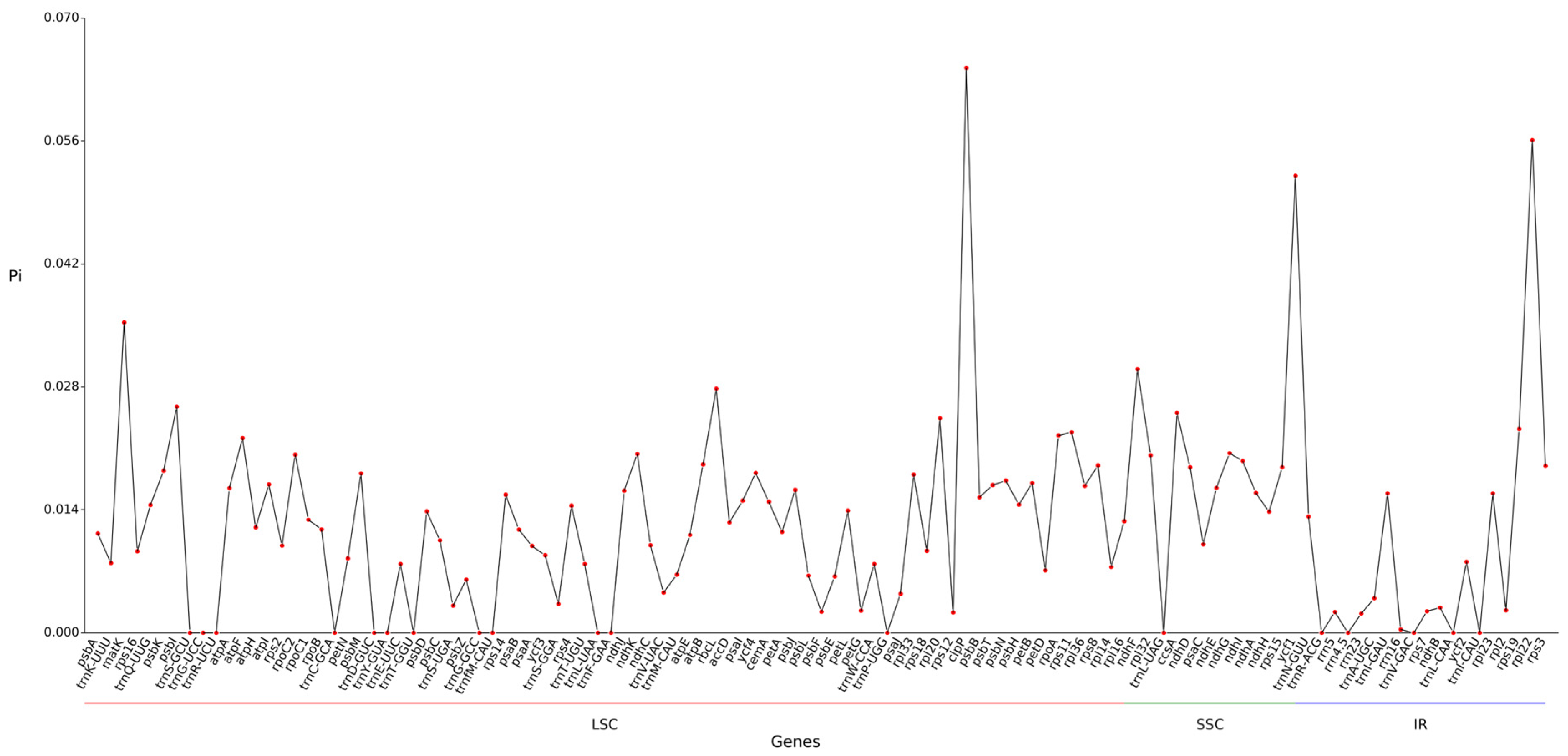

2.7. Nucleic Acid Diversity Pi Analysis

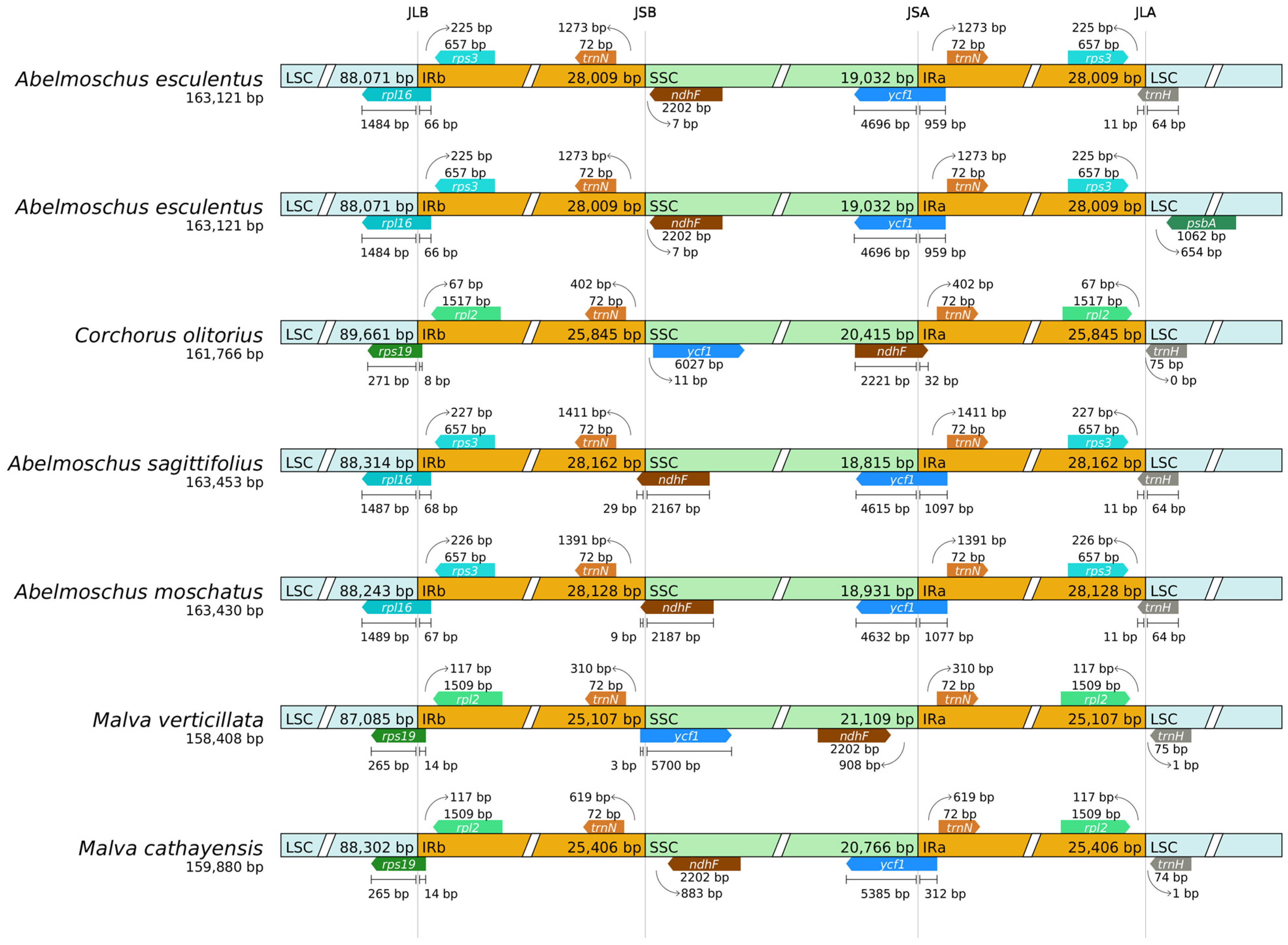

2.8. Boundary Analysis

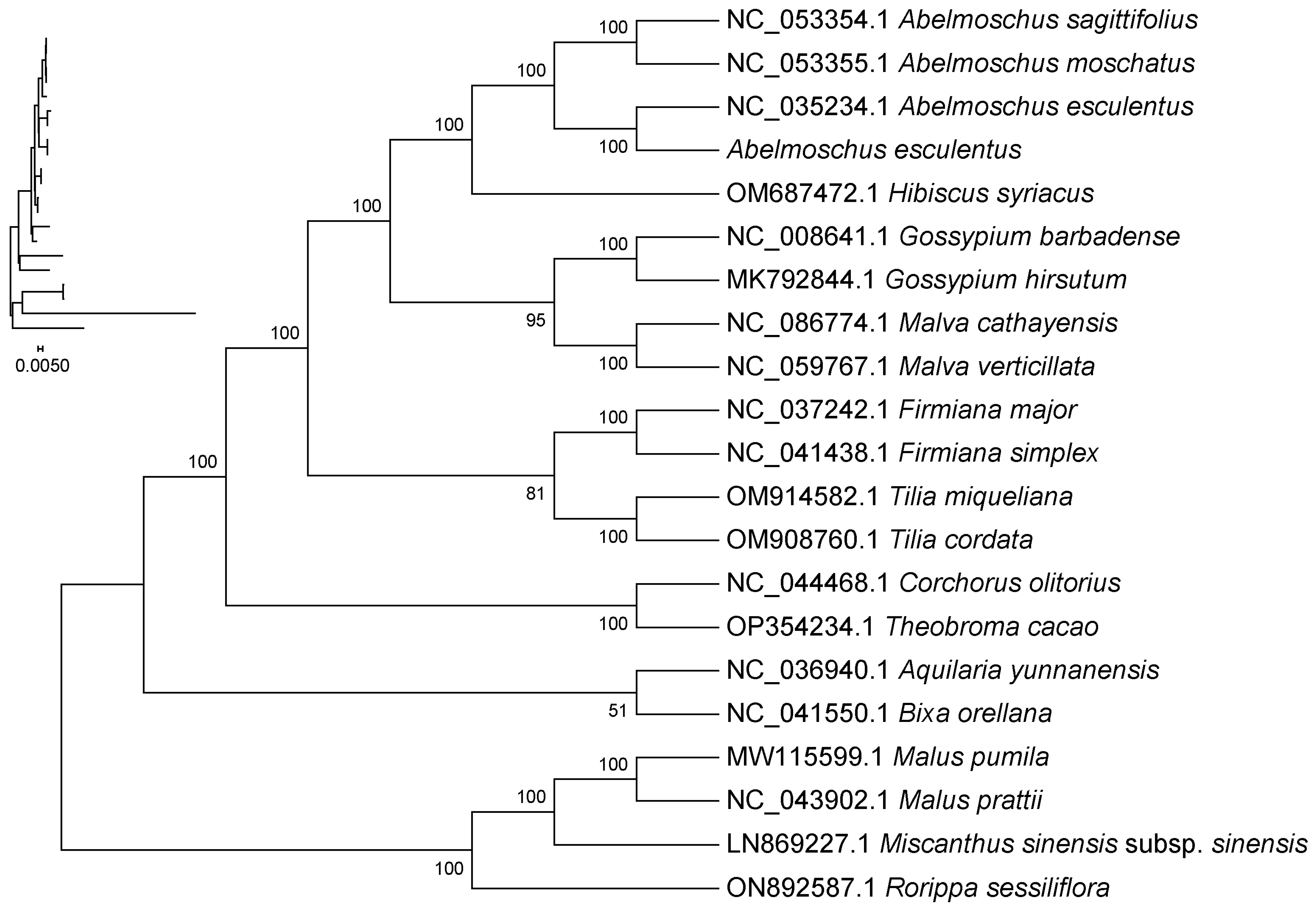

2.9. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Discussion

3.1. Conservation and Uniqueness of Genomic Structure

3.2. Biological Interpretation of Function-Related Traits

3.3. Distribution Characteristics of Repetitive Sequences

3.4. Gene Dialogue and Evolutionary Dynamics Among Organelles

3.5. The Taxonomic Significance of Phylogenetic Results

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Sequencing

4.2. Chloroplast Genome Assembly and Annotation

4.3. Codon Usage and Repeat Sequence Analysis

4.4. Selective Pressure and Nucleotide Diversity Analysis

4.5. IR Boundary and Comparative Genomics Analysis

4.6. Methods for Constructing Phylogenetic Trees and Parameter Settings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sorapong, B. Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench) as a Valuable Vegetable of the World. Ratar. Povrt. 2012, 49, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemede, H.F.; Ratta, N.; Haki, G.D.; Ashagrie, Z.W. Nutritional quality and health benefits of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus): A review. J. Food Process. Technol. 2015, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, P.; Chauhana, V.; Tiwaria, B.K.; Chauhan, S.S.; Simonb, S.; Bilalc, S.; Abidia, A.B. An overview on okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) and it’s importance as a nutritive vegetable in the world. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 2014, 4, 227–233. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Qi, J.; Luo, J.; Qin, W.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, D.; Lin, D.; Li, S.; Dong, H.; et al. Okra in Food Field: Nutritional Value, Health Benefits and Effects of Processing Methods on Quality. Food Rev. Int. 2021, 37, 67–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrogojski, J.; Adamiec, M.; Luciński, R. The Chloroplast Genome: A Review. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2020, 42, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, C.J.; Barbrook, A.C.; Koumandou, V.L.; Nisbet, R.E.R.; Symington, H.A.; Wightman, T.F. Evolution of the Chloroplast Genome. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2003, 358, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniell, H.; Lin, C.-S.; Yu, M.; Chang, W.-J. Chloroplast Genomes: Diversity, Evolution, and Applications in Genetic Engineering. Genome. Biol. 2016, 17, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, W.-B.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Shahzad, K.; Li, Z.-H. Comparative Chloroplast Genomics of Dipsacales Species: Insights Into Sequence Variation, Adaptive Evolution, and Phylogenetic Relationships. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfeil, B.E.; Brubaker, C.L.; Craven, L.A.; Crisp, M.D. Phylogeny of Hibiscus and the Tribe Hibisceae (Malvaceae) Using Chloroplast DNA Sequences of ndhF and the Rpl16 Intron. Syst. Bot. 2002, 27, 333–350. [Google Scholar]

- Ramya, P.; Bhat, K.V. Analysis of phylogenetic relationships in Abelmoschus species (Malvaceae) using ribosomal and chloroplast intergenic spacers. Indian J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2012, 72, 445–453. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Ye, G.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z. Complete Chloroplast Genomes of Three Important Species, Abelmoschus moschatus, A. Manihot and A. Sagittifolius: Genome Structures, Mutational Hotspots, Comparative and Phylogenetic Analysis in Malvaceae. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, T.; Shi, D.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, L.; Ye, L. The Whole Chloroplast Genome in Abelmoschus esculentus L. Moench. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2023, 51, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, W.; He, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Du, C.; Du, H.; et al. The Genome of Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) Provides Insights into Its Genome Evolution and High Nutrient Content. Hortic. Res. 2023, 10, uhad120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Oh, Y.J.; Han, K.Y.; Kim, G.H.; Ko, J.; Park, J. The Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of Hibiscus Syriacus L. ‘Mamonde’ (Malvaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2019, 4, 558–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.I.H.; Azuma, J.-I.; Sakamoto, M. Complete Nucleotide Sequence of the Cotton (Gossypium barbadense L.) Chloroplast Genome with a Comparative Analysis of Sequences among 9 Dicot Plants. Genes Genet. Syst. 2006, 81, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, J.O.; Yerramsetty, P.; Zielinski, A.M.; Mure, C.M. Photosynthetic Gene Expression in Higher Plants. Photosynth. Res. 2013, 117, 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, J.D.; Stein, D.B. Conservation of Chloroplast Genome Structure among Vascular Plants. Curr. Genet. 1986, 10, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yang, B.; Zhu, W.; Sun, L.; Tian, J.; Wang, X. The Complete Chloroplast Genome Sequence of Mahonia bealei (Berberidaceae) Reveals a Significant Expansion of the Inverted Repeat and Phylogenetic Relationship with Other Angiosperms. Gene 2013, 528, 120–131, Erratum in Gene 2014, 533, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.I.; Soreng, R.J. Migration of Endpoints of Two Genes Relative to Boundaries between Regions of the Plastid Genome in the Grass Family (Poaceae). Am. J Bot. 2010, 97, 874–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-Y.; Yang, J.-X.; Bai, M.-Z.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Liu, Z.-J. The Chloroplast Genome Evolution of Venus Slipper (Paphiopedilum): IR Expansion, SSC Contraction, and Highly Rearranged SSC Regions. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Yang, D.-G.; Li, W.; Zhou, X.-J.; Pei, X.-Y.; Liu, Y.-G.; He, K.-L.; Zhang, W.-S.; Ren, Z.-Y.; et al. Comparative Chloroplast Genomics of Gossypium Species: Insights Into Repeat Sequence Variations and Phylogeny. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashi, Y.; King, D. Simple Sequence Repeats as Advantageous Mutators in Evolution. Trends Genet. 2006, 22, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, D.A. Complete Chloroplast Genome of Abutilon fruticosum: Genome Structure, Comparative and Phylogenetic Analysis. Plants 2021, 10, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Du, F. Different Natural Selection Pressures on the atpF Gene in Evergreen Sclerophyllous and Deciduous Oak Species: Evidence from Comparative Analysis of the Complete Chloroplast Genome of Quercus aquifolioides with Other Oak Species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruster, U.; Correa Galvis, V.; Kunz, H.-H.; Strand, D.D. The Regulation of the Chloroplast Proton Motive Force Plays a Key Role for Photosynthesis in Fluctuating Light. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 37, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christin, P.-A.; Salamin, N.; Muasya, A.M.; Roalson, E.H.; Russier, F.; Besnard, G. Evolutionary Switch and Genetic Convergence on rbcL Following the Evolution of C4 Photosynthesis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008, 25, 2361–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, E.E.; Lotzer, J.; Eberle, M. Codon Usage in Plant Genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989, 17, 477–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandivier, L.E.; Anderson, S.J.; Foley, S.W.; Gregory, B.D. The Conservation and Function of RNA Secondary Structure in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2016, 67, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, D.P.; Herbeck, J.T. Evolutionary Patterns of Codon Usage in the Chloroplast Gene Rbc L. J. Mol. Evol. 2003, 56, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgante, M.; Hanafey, M.; Powell, W. Microsatellites Are Preferentially Associated with Nonrepetitive DNA in Plant Genomes. Nat. Genet. 2002, 30, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velayudha Vimala Kumar, K.; Srikakulam, N.; Padbhanabhan, P.; Pandi, G. Deciphering microRNAs and Their Associated Hairpin Precursors in a Non-Model Plant, Abelmoschus esculentus. Non-Coding RNA 2017, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Kou, L.; Wei, J.; Wang, W. The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus): Using Nanopore Long Reads to Investigate Gene Transfer from Chloroplast Genomes and Rearrangements of Mitochondrial DNA Molecules. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillis, D.M.; Bull, J.J. An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Syst. Biol. 1993, 42, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.; Sutar, S.; Joseph, J.K.; Malik, S.; Rao, S.; Yadav, S.; Bhat, K.V. A systematic review of the genus Abelmoschus (Malvaceae). Rheedea 2015, 25, 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boetzer, M.; Henkel, C.V.; Jansen, H.J.; Butler, D.; Pirovano, W. Scaffolding Pre-Assembled Contigs Using SSPACE. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 578–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boetzer, M.; Pirovano, W. Toward almost closed genomes with GapFiller. Genome Biol. 2012, 13, R56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, D.; Chen, G.-L.; LoCascio, P.F.; Land, M.L.; Larimer, F.W.; Hauser, L.J. Prodigal: Prokaryotic Gene Recognition and Translation Initiation Site Identification. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J.; Finn, R.D.; Eddy, S.R.; Bateman, A.; Punta, M. Challenges in Homology Search: HMMER3 and Convergent Evolution of Coiled-Coil Regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laslett, D. ARAGORN, a Program to Detect tRNA Genes and tmRNA Genes in Nucleotide Sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, S.; Lehwark, P.; Bock, R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) Version 1.3.1: Expanded Toolkit for the Graphical Visualization of Organellar Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W59–W64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S. The Vmatch Large Scale Sequence Analysis Software. Available online: http://vmatch.de/vmweb.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Katoh, K. MAFFT Version 5: Improvement in Accuracy of Multiple Sequence Alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: A Toolkit Incorporating Gamma-Series Methods and Sliding Window Strategies. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2010, 8, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: A Software for Comprehensive Analysis of DNA Polymorphism Data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.R.; Stothard, P. The CGView Server: A Comparative Genomics Tool for Circular Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, W181–W184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling, A.C.E.; Mau, B.; Blattner, F.R.; Perna, N.T. Mauve: Multiple Alignment of Conserved Genomic Sequence With Rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1394–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestro, D.; Michalak, I. raxmlGUI: A Graphical Front-End for RAxML. Org. Divers. Evol. 2012, 12, 335–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | A Content/% | C Content/% | G Content/% | T Content/% | GC Content/% | Base Length/bp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSC | 32.08 | 17.78 | 16.77 | 33.37 | 34.55 | 88,071 |

| SSC | 33.87 | 16.36 | 15.12 | 34.64 | 31.48 | 19,032 |

| IRa | 29.53 | 21.66 | 20.30 | 28.51 | 41.97 | 28,009 |

| IRb | 28.51 | 20.30 | 21.66 | 29.53 | 41.97 | 28,009 |

| Total volume | 31.24 | 18.71 | 18.02 | 32.02 | 36.74 | 163,121 |

| Category | Gene Group | Gene Name |

|---|---|---|

| Photosynthesis | Subunits of photosystem I | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ |

| Subunits of photosystem II | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, psbZ | |

| Subunits of NADH dehydrogenase | ndhA*, ndhB*(2), ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK | |

| Subunits of cytochrome b/f complex | petA, petB*, petD*, petG, petL, petN | |

| Subunits of ATP synthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF*, atpH, atpI | |

| Large subunit of rubisco | rbcL | |

| Subunits photochlorophyllide reductase | - | |

| Self-replication | Proteins of the large ribosomal subunit | rpl14, rpl16*, rpl2*(2), rpl20, rpl22(2), rpl23(2), rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 |

| Proteins of the small ribosomal subunit | rps11, rps12**(2), rps14, rps15, rps16*, rps18, rps19(2), rps2, rps3(2), rps4, rps7(2), rps8 | |

| Subunits of RNA polymerase | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1*, rpoC2 | |

| Ribosomal RNAs | rrn16(2), rrn23(2), rrn4.5(2), rrn5(2) | |

| Transfer RNAs | trnA-UGC*(2), trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnE-UUC, trnF-GAA, trnG-GCC, trnG-UCC*, trnH-GUG, trnI-CAU(2), trnI-GAU*(2), trnK-UUU*, trnL-CAA(2), trnL-UAA*, trnL-UAG, trnM-CAU, trnN-GUU(2), trnP-UGG, trnQ-UUG, trnR-ACG(2), trnR-UCU, trnS-GCU, trnS-GGA, trnS-UGA, trnT-GGU, trnT-UGU, trnV-GAC(2), trnV-UAC*, trnW-CCA, trnY-GUA, trnfM-CAU | |

| Other genes | Maturase | matK |

| Protease | clpP** | |

| Envelope membrane protein | cemA | |

| Acetyl-CoA carboxylase | accD | |

| c-type cytochrome synthesis gene | ccsA | |

| Translation initiation factor | - | |

| other | - | |

| Genes of unknown function | Conserved hypothetical chloroplast ORF | ycf1, ycf2(2), ycf3**, ycf4 |

| Symbol | Codon | No. | RSCU | Symbol | Codon | No. | RSCU | Symbol | Codon | No. | RSCU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ter | UAA | 43 | 1.6539 | Lys | AAA | 897 | 1.5088 | Arg | AGA | 399 | 1.7616 |

| Ter | UAG | 17 | 0.6537 | Lys | AAG | 292 | 0.4912 | Arg | AGG | 148 | 0.6534 |

| Ter | UGA | 18 | 0.6924 | Leu | CUA | 332 | 0.8286 | Arg | CGA | 317 | 1.3998 |

| Ala | GCA | 332 | 1.0312 | Leu | CUC | 148 | 0.3696 | Arg | CGC | 111 | 0.4902 |

| Ala | GCC | 213 | 0.6616 | Leu | CUG | 152 | 0.3792 | Arg | CGG | 89 | 0.393 |

| Ala | GCG | 169 | 0.5248 | Leu | CUU | 492 | 1.2282 | Arg | CGU | 295 | 1.3026 |

| Ala | GCU | 574 | 1.7828 | Leu | UUA | 789 | 1.9692 | Ser | AGC | 103 | 0.3654 |

| Cys | UGC | 63 | 0.496 | Leu | UUG | 491 | 1.2252 | Ser | AGU | 343 | 1.2168 |

| Cys | UGU | 191 | 1.504 | Met | AUA | 0 | 0 | Ser | UCA | 356 | 1.263 |

| Asp | GAC | 185 | 0.4062 | Met | AUC | 0 | 0 | Ser | UCC | 259 | 0.9192 |

| Asp | GAU | 726 | 1.5938 | Met | AUG | 526 | 7 | Ser | UCG | 147 | 0.5214 |

| Glu | GAA | 898 | 1.508 | Met | AUU | 0 | 0 | Ser | UCU | 483 | 1.7136 |

| Glu | GAG | 293 | 0.492 | Met | CUG | 0 | 0 | Thr | ACA | 353 | 1.2108 |

| Phe | UUC | 424 | 0.6578 | Met | GUG | 0 | 0 | Thr | ACC | 227 | 0.7788 |

| Phe | UUU | 865 | 1.3422 | Met | UUG | 0 | 0 | Thr | ACG | 138 | 0.4736 |

| Gly | GGA | 619 | 1.5368 | Asn | AAC | 250 | 0.4638 | Thr | ACU | 448 | 1.5368 |

| Gly | GGC | 173 | 0.4296 | Asn | AAU | 828 | 1.5362 | Val | GUA | 470 | 1.5088 |

| Gly | GGG | 290 | 0.72 | Pro | CCA | 258 | 1.1048 | Val | GUC | 151 | 0.4848 |

| Gly | GGU | 529 | 1.3136 | Pro | CCC | 174 | 0.7452 | Val | GUG | 170 | 0.5456 |

| His | CAC | 139 | 0.5054 | Pro | CCG | 131 | 0.5612 | Val | GUU | 455 | 1.4608 |

| His | CAU | 411 | 1.4946 | Pro | CCU | 371 | 1.5888 | Trp | UGG | 403 | 1 |

| Ile | AUA | 613 | 0.9354 | Gln | CAA | 625 | 1.549 | Tyr | UAC | 172 | 0.4018 |

| Ile | AUC | 371 | 0.5661 | Gln | CAG | 182 | 0.451 | Tyr | UAU | 684 | 1.5982 |

| Ile | AUU | 982 | 1.4985 |

| Length | F | P | R | C | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 26 |

| 31 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 9 |

| 32 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 12 |

| 33 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| 34 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 10 |

| 35 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| 36 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 37 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 39 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 40 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 41 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 43 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 46 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 52 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 53 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 28,009 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 28 | 28 | 24 | 11 | 91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dong, J.; Du, G.; Ji, Q.; An, X.; Zhu, Z.; Tang, S.; Luo, X.; Chen, C.; Liu, T.; Zou, L.; et al. Characteristics and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Complete Chloroplast Genome of Abelmoschus esculentus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010118

Dong J, Du G, Ji Q, An X, Zhu Z, Tang S, Luo X, Chen C, Liu T, Zou L, et al. Characteristics and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Complete Chloroplast Genome of Abelmoschus esculentus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010118

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Junyuan, Guanghui Du, Qingqing Ji, Xingcai An, Ziyi Zhu, Shenyue Tang, Xiahong Luo, Changli Chen, Tingting Liu, Lina Zou, and et al. 2026. "Characteristics and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Complete Chloroplast Genome of Abelmoschus esculentus" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010118

APA StyleDong, J., Du, G., Ji, Q., An, X., Zhu, Z., Tang, S., Luo, X., Chen, C., Liu, T., Zou, L., Li, S., Chen, J., & An, X. (2026). Characteristics and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Complete Chloroplast Genome of Abelmoschus esculentus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010118