The Apelinergic System in Kidney Disease: Novel Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

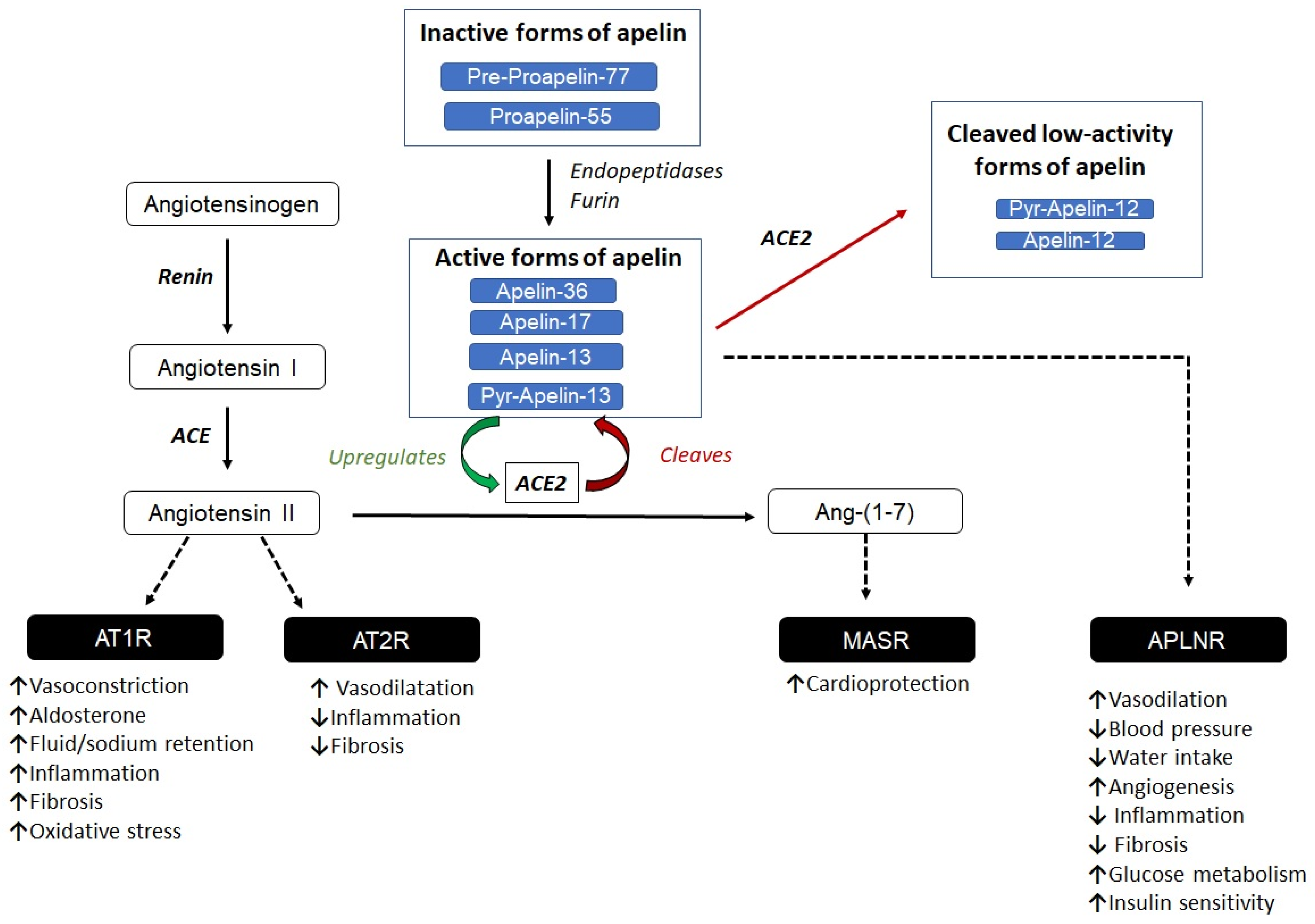

2. The Apelinergic System

3. Role of Apelin in Diseases

3.1. The Role of Apelin in Inflammatory and Fibrotic Processes

3.2. Apelin and Cancer: Role in Angiogenic Processes

3.3. Apelin and the Nervous System: Role in Neural Damage

3.4. The Role of Apelin in Cardiovascular Diseases

3.5. The Role of Apelin in Hypertension and CKD

4. The Role of Apelin in Human Diabetes and CKD

5. Apelin Analogs and Their Therapeutic Potential

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ortiz, A. RICORS2040: The Need for Collaborative Research in Chronic Kidney Disease. Clin. Kidney J. 2021, 15, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease, 1990–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020, 395, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naaman, S.C.; Bakris, G.L. Diabetic Nephropathy: Update on Pillars of Therapy Slowing Progression. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, 1574–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, A.I.; Stevens, R.J.; Manley, S.E.; Bilous, R.W.; Cull, C.A.; Holman, R.R. UKPDS GROUP Development and Progression of Nephropathy in Type 2 Diabetes: The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS 64). Kidney Int. 2003, 63, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-T.; Xu, X.; Lim, P.S.; Hung, K.-Y. Worldwide Epidemiology of Diabetes-Related End-Stage Renal Disease, 2000–2015. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alicic, R.Z.; Rooney, M.T.; Tuttle, K.R. Diabetic Kidney Disease: Challenges, Progress, and Possibilities. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2017, 12, 2032–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Hang, X.; Wei, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, L. Crosstalk among Podocytes, Glomerular Endothelial Cells and Mesangial Cells in Diabetic Kidney Disease: An Updated Review. Cell Commun. Signal 2024, 22, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viggiano, D.; Joshi, R.; Borriello, G.; Cacciola, G.; Gonnella, A.; Gigliotti, A.; Nigro, M.; Gigliotti, G. SGLT2 Inhibitors: The First Endothelial-Protector for Diabetic Nephropathy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabias, B.M.; Konstantopoulos, K. The Physical Basis of Renal Fibrosis: Effects of Altered Hydrodynamic Forces on Kidney Homeostasis. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2014, 306, F473–F485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borri, M.; Jacobs, M.E.; Carmeliet, P.; Rabelink, T.J.; Dumas, S.J. Endothelial Dysfunction in the Aging Kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2025, 328, F542–F562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg Sibony, R.; Segev, O.; Dor, S.; Raz, I. Drug Therapies for Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steven, S.; Oelze, M.; Hanf, A.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Kashani, F.; Roohani, S.; Welschof, P.; Kopp, M.; Gödtel-Armbrust, U.; Xia, N.; et al. The SGLT2 Inhibitor Empagliflozin Improves the Primary Diabetic Complications in ZDF Rats. Redox Biol. 2017, 13, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oeseburg, H.; de Boer, R.A.; Buikema, H.; van der Harst, P.; van Gilst, W.H.; Silljé, H.H.W. Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Prevents Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Endothelial Cell Senescence through the Activation of Protein Kinase A. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 1407–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigiyama, F.; Kumashiro, N.; Miyagi, M.; Ikehara, K.; Kanda, E.; Uchino, H.; Hirose, T. Effectiveness of Dapagliflozin on Vascular Endothelial Function and Glycemic Control in Patients with Early-Stage Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: DEFENCE Study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2017, 16, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatemoto, K.; Hosoya, M.; Habata, Y.; Fujii, R.; Kakegawa, T.; Zou, M.-X.; Kawamata, Y.; Fukusumi, S.; Hinuma, S.; Kitada, C.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Endogenous Peptide Ligand for the Human APJ Receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1998, 251, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoya, M.; Kawamata, Y.; Fukusumi, S.; Fujii, R.; Habata, Y.; Hinuma, S.; Kitada, C.; Honda, S.; Kurokawa, T.; Onda, H.; et al. Molecular and Functional Characteristics of APJ. Tissue Distribution of mRNA and Interaction with the Endogenous Ligand Apelin. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 21061–21067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyimanu, D.; Chapman, F.A.; Gallacher, P.J.; Kuc, R.E.; Williams, T.L.; Newby, D.E.; Maguire, J.J.; Davenport, A.P.; Dhaun, N. Apelin Is Expressed throughout the Human Kidney, Is Elevated in Chronic Kidney Disease & Associates Independently with Decline in Kidney Function. Brit J. Clin. Pharma 2022, 88, 5295–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwangbo, C.; Wu, J.; Papangeli, I.; Adachi, T.; Sharma, B.; Park, S.; Zhao, L.; Ju, H.; Go, G.; Cui, G.; et al. Endothelial APLNR Regulates Tissue Fatty Acid Uptake and Is Essential for Apelin’s Glucose-Lowering Effects. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaad4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hus-Citharel, A.; Bouby, N.; Frugière, A.; Bodineau, L.; Gasc, J.-M.; Llorens-Cortes, C. Effect of Apelin on Glomerular Hemodynamic Function in the Rat Kidney. Kidney Int. 2008, 74, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habchi, M.; Duvillard, L.; Cottet, V.; Brindisi, M.-C.; Bouillet, B.; Beacco, M.; Crevisy, E.; Buffier, P.; Baillot-Rudoni, S.; Verges, B.; et al. Circulating Apelin Is Increased in Patients with Type 1 or Type 2 Diabetes and Is Associated with Better Glycaemic Control. Clin. Endocrinol. 2014, 81, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.P.; Fragoso, A.; Silva, C.; Viegas, C.; Tavares, N.; Guilherme, P.; Santos, N.; Rato, F.; Camacho, A.; Cavaco, C.; et al. What Is the Role of Apelin Regarding Cardiovascular Risk and Progression of Renal Disease in Type 2 Diabetic Patients with Diabetic Nephropathy? Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 247649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Fan, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, N.; Song, Y.; Ren, F.; Shen, C.; Shen, J.; et al. The Association between Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms of the Apelin Gene and Diabetes Mellitus in a Chinese Population. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 29, 1397–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tora, G.; Jiang, J.; Bostwick, J.S.; Gargalovic, P.S.; Onorato, J.M.; Luk, C.E.; Generaux, C.; Xu, C.; Galella, M.A.; Wang, T.; et al. Identification of 6-Hydroxy-5-Phenyl Sulfonylpyrimidin-4(1H)-One APJ Receptor Agonists. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 50, 128325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Clarke, A.; Han, Y.; Chao, H.J.; Bostwick, J.; Schumacher, W.; Wang, T.; Yan, M.; Hsu, M.-Y.; Simmons, E.; et al. Biphenyl Acid Derivatives as APJ Receptor Agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 10456–10465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.T.; Cavaglieri, R.C.; Feliers, D. Apelin Retards the Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2013, 304, F788–F800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhong, X.; Tan, Y.-X.; Liu, D. Apelin-13 Alleviates Diabetic Nephropathy by Enhancing Nitric Oxide Production and Suppressing Kidney Tissue Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 48, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, F.A.; Nyimanu, D.; Maguire, J.J.; Davenport, A.P.; Newby, D.E.; Dhaun, N. The Therapeutic Potential of Apelin in Kidney Disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2021, 17, 840–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, X. Apelin Involved in Progression of Diabetic Nephropathy by Inhibiting Autophagy in Podocytes. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.; Landsman, M.; Pelletier, S.; Alamri, B.N.; Anini, Y.; Rainey, J.K. Proapelin Is Processed Extracellularly in a Cell Line-Dependent Manner with Clear Modulation by Proprotein Convertases. Amino Acids 2019, 51, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couvineau, P.; Llorens-Cortes, C. Metabolically Stable Apelin Analogs: Development and Functional Role in Water Balance and Cardiovascular Function. Clin. Sci. 2025, 139, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, A.; O’Rourke, S.T. Vascular Effects of Apelin: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 190, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, A.A.; Vergara, A.; Wang, X.; Vederas, J.C.; Oudit, G.Y. Apelin Pathway in Cardiovascular, Kidney, and Metabolic Diseases: Therapeutic Role of Apelin Analogs and Apelin Receptor Agonists. Peptides 2022, 147, 170697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, P.; De Loor, H.; Decuypere, J.-P.; Vennekens, R.; Llorens-Cortes, C.; Mekahli, D.; Bammens, B. On Methods for the Measurement of the Apelin Receptor Ligand Apelin. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesmin, C.; Dubois, M.; Becher, F.; Fenaille, F.; Ezan, E. Liquid Chromatography/Tandem Mass Spectrometry Assay for the Absolute Quantification of the Expected Circulating Apelin Peptides in Human Plasma. Rapid Commun. Mass. Spectrom. 2010, 24, 2875–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japp, A.G.; Cruden, N.L.; Amer, D.A.B.; Li, V.K.Y.; Goudie, E.B.; Johnston, N.R.; Sharma, S.; Neilson, I.; Webb, D.J.; Megson, I.L.; et al. Vascular Effects of Apelin In Vivo in Man. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 52, 908–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, B.F.; Heiber, M.; Chan, A.; Heng, H.H.Q.; Tsui, L.-C.; Kennedy, J.L.; Shi, X.; Petronis, A.; George, S.R.; Nguyen, T. A Human Gene That Shows Identity with the Gene Encoding the Angiotensin Receptor Is Located on Chromosome 11. Gene 1993, 136, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagamajalu, S.; Rex, D.A.B.; Palollathil, A.; Shetty, R.; Bhat, G.; Cheung, L.W.T.; Prasad, T.S.K. A Pathway Map of AXL Receptor-Mediated Signaling Network. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 15, 143–148, Erratum in J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 15, 149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12079-020-00583-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, F.A.; Maguire, J.J.; Newby, D.E.; Davenport, A.P.; Dhaun, N. Targeting the Apelin System for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Diseases. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 2683–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuba, K.; Sato, T.; Imai, Y.; Yamaguchi, T. Apelin and Elabela/Toddler; Double Ligands for APJ/Apelin Receptor in Heart Development, Physiology, and Pathology. Peptides 2019, 111, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, N.A.; Dupré, D.J.; Rainey, J.K. The Apelin Receptor: Physiology, Pathology, Cell Signalling, and Ligand Modulation of a Peptide-Activated Class A GPCR. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014, 92, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, G. G Protein-Coupled Receptor Hetero-Dimerization: Contribution to Pharmacology and Function. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 158, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borroto-Escuela, D.O.; Romero-Fernandez, W.; Tarakanov, A.O.; Gómez-Soler, M.; Corrales, F.; Marcellino, D.; Narvaez, M.; Frankowska, M.; Flajolet, M.; Heintz, N.; et al. Characterization of the A2AR–D2R Interface: Focus on the Role of the C-Terminal Tail and the Transmembrane Helices. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 402, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, B.; Cai, X.; Jiang, Y.; Karteris, E.; Chen, J. Heterodimerization of Apelin Receptor and Neurotensin Receptor 1 Induces Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and Cell Proliferation via Gαq-mediated Mechanism. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014, 18, 2071–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Bai, B.; Du, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H. Heterodimerization of Human Apelin and Kappa Opioid Receptors: Roles in Signal Transduction. Cell. Signal. 2012, 24, 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Kadowaki, A.; Suzuki, T.; Ito, H.; Watanabe, H.; Imai, Y.; Kuba, K. Loss of Apelin Augments Angiotensin II-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction and Pathological Remodeling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayari, H.; Chraibi, A. Apelin-13 Decreases Epithelial Sodium Channel (ENaC) Expression and Activity in Kidney Collecting Duct Cells. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Duan, S.-B.; Wang, L.; Luo, X.-Q.; Wang, H.-S.; Deng, Y.-H.; Wu, X.; Wu, T.; Yan And, P.; Kang, Y.-X. Apelin-13 Alleviates Contrast-Induced Acute Kidney Injury by Inhibiting Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Ren. Fail. 2023, 45, 2179852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, K.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, G.; Yu, Z. Apelin-13 Inhibits the Adhesion of Monocytes to Endothelial Cells via the Gfi1/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2025, 72, 1363–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Zhang, J. RUNX3-Activated Apelin Signaling Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Fibrosis in Diabetic Nephropathy by Regulation of the SIRT1/FOXO Pathway. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2024, 16, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Feng, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Lv, X.; Yang, Y. Relationship between Apelin/APJ Signaling, Oxidative Stress, and Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 8866725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fibbi, B.; Marroncini, G.; Naldi, L.; Peri, A. The Yin and Yang Effect of the Apelinergic System in Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glassford, A.J.; Yue, P.; Sheikh, A.Y.; Chun, H.J.; Zarafshar, S.; Chan, D.A.; Reaven, G.M.; Quertermous, T.; Tsao, P.S. HIF-1 Regulates Hypoxia- and Insulin-Induced Expression of Apelin in Adipocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 293, E1590–E1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berta, J.; Hoda, M.A.; Laszlo, V.; Rozsas, A.; Garay, T.; Torok, S.; Grusch, M.; Berger, W.; Paku, S.; Renyi-Vamos, F.; et al. Apelin promotes lymphangiogenesis and lymph node metastasis. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 4426–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.-H.; Chang, S.L.-Y.; Khanh, P.M.; Trang, N.T.N.; Liu, S.-C.; Tsai, H.-C.; Chang, A.-C.; Lin, J.-Y.; Chen, P.-C.; Liu, J.-F.; et al. Apelin Promotes Prostate Cancer Metastasis by Downregulating TIMP2 via Increases in miR-106a-5p Expression. Cells 2022, 11, 3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribesalgo, I.; Hoffmann, D.; Zhang, Y.; Kavirayani, A.; Lazovic, J.; Berta, J.; Novatchkova, M.; Pai, T.-P.; Wimmer, R.A.; László, V.; et al. Apelin Inhibition Prevents Resistance and Metastasis Associated with Anti-Angiogenic Therapy. EMBO Mol. Med. 2019, 11, e9266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inukai, K.; Kise, K.; Hayashi, Y.; Jia, W.; Muramatsu, F.; Okamoto, N.; Konishi, H.; Akuta, K.; Kidoya, H.; Takakura, N. Cancer Apelin Receptor Suppresses Vascular Mimicry in Malignant Melanoma. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2023, 29, 1610867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, S.; Wu, Z.; Li, W.; Wu, R.; Wang, Z.; Liu, W. Apelin-13 Protects Neurons by Attenuating Early-Stage Postspinal Cord Injury Apoptosis In Vitro. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Zhou, J.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, L. A Reactive Oxygen Species-Responsive Hydrogel Loaded with Apelin-13 Promotes the Repair of Spinal Cord Injury by Regulating Macrophage M1/M2 Polarization and Neuroinflammation. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdinal, F.; Limanan, D.; Rini, R.D.; Alexsandro, R.; Helmi, R. Elevated Levels of Apelin-36 in Heart Failure Due to Chronic Systemic Hypoxia. Int. J. Angiol. 2019, 28, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.K.; Cheng, R.; Nguyen, T.; Fan, T.; Kariyawasam, A.P.; Liu, Y.; Osmond, D.H.; George, S.R.; O’Dowd, B.F. Characterization of Apelin, the Ligand for the APJ Receptor. J. Neurochem. 2000, 74, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gupta, R.C.; Rastogi, S.; Kohli, S.; Sabbah, M.S.; Zhang, K.; Mohyi, P.; Hogie, M.; Fischer, Y.; Sabbah, H.N. Effects of Acute Intravenous Infusion of Apelin on Left Ventricular Function in Dogs with Advanced Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2013, 19, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gargalovic, P.; Wong, P.; Onorato, J.; Finlay, H.; Wang, T.; Yan, M.; Crain, E.; St-Onge, S.; Héroux, M.; Bouvier, M.; et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of a Small-Molecule APJ (Apelin Receptor) Agonist, BMS-986224, as a Potential Treatment for Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2021, 14, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, H.J.; Ali, Z.A.; Kojima, Y.; Kundu, R.K.; Sheikh, A.Y.; Agrawal, R.; Zheng, L.; Leeper, N.J.; Pearl, N.E.; Patterson, A.J.; et al. Apelin Signaling Antagonizes Ang II Effects in Mouse Models of Atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 3343–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaydarski, L.; Dimitrova, I.N.; Stanchev, S.; Iliev, A.; Kotov, G.; Kirkov, V.; Stamenov, N.; Dikov, T.; Georgiev, G.P.; Landzhov, B. Unraveling the Complex Molecular Interplay and Vascular Adaptive Changes in Hypertension-Induced Kidney Disease. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekerci, R.; Acar, N.; Tepekoy, F.; Ustunel, I.; Keles-Celik, N. Apelin/APJ Expression in the Heart and Kidneys of Hypertensive Rats. Acta Histochem. 2018, 120, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani Hekmat, A.; Najafipour, H.; Nekooian, A.A.; Esmaeli-Mahani, S.; Javanmardi, K. Cardiovascular Responses to Apelin in Two-Kidney–One-Clip Hypertensive Rats and Its Receptor Expression in Ischemic and Non-Ischemic Kidneys. Regul. Pept. 2011, 172, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Niloy, S.I.; O’Rourke, S.T.; Sun, C. Chronic Effects of Apelin on Cardiovascular Regulation and Angiotensin II-Induced Hypertension. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, F.A.; Melville, V.; Godden, E.; Morrison, B.; Bruce, L.; Maguire, J.J.; Davenport, A.P.; Newby, D.E.; Dhaun, N. Cardiovascular and Renal Effects of Apelin in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meral, C.; Tascilar, E.; Karademir, F.; Tanju, I.A.; Cekmez, F.; Ipcioglu, O.M.; Ercin, C.N.; Gocmen, I.; Dogru, T. Elevated Plasma Levels of Apelin in Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 23, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayem, S.M.E.; Battah, A.A.; Bohy, A.E.M.E.; Yousef, R.N.; Ahmed, A.M.; Talaat, A.A. Apelin, Nitric Oxide and Vascular Affection in Adolescent Type 1 Diabetic Patients. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 5, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsehmawy, A.A.E.W.; El-Toukhy, S.E.; Seliem, N.M.A.; Moustafa, R.S.; Mohammed, D.S. Apelin and Chemerin as Promising Adipokines in Children with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. DMSO 2019, 12, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Yin, J.; Zeng, X. Promoting Effects of the Adipokine, Apelin, on Diabetic Nephropathy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhai, A.; Xu, H.; Ma, S.; Liu, Y. Expression of Apelin-13 and Its Negative Correlation with TGF-β1 in Patients with Diabetic Kidney Disease. Exp. Ther. Med. 2024, 27, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdemir, N.; Toraman, A.; Taneli, F.; Yurekli, B.S.; Hekimsoy, Z. An Evaluation of Both Serum Klotho/FGF-23 and Apelin-13 for Detection of Diabetic Nephropathy. Hormones 2023, 22, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonem, A.; Duran, C.; Unal, M.; Ipcioglu, O.M.; Ozcan, O. Plasma Apelin and Asymmetric Dimethylarginine Levels in Type 2 Diabetic Patients with Diabetic Retinopathy. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2009, 84, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- İçen, G.; Dağlıoğlu, G.; Evran, M. Evaluation of Apelin-13 Levels in Patients with Diabetic Nephropathy. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2023, 55, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, X. Low Serum Apelin Levels Are Associated with Mild Cognitive Impairment in Type 2 Diabetic Patients. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022, 22, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakran, N.A.; Cherif, S.; Algburi, F.S. The Relationship of Irisin, Apelin-13, and Immunological Markers Il-1α & Amp, Il-1β with Diabetes in Kidney Failure Patients. Cell Mol. Biol. 2025, 70, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.C.; Spielmann, G.; Yang, S.; Compton, S.L.E.; Jones, L.W.; Irwin, M.L.; Ligibel, J.A.; Meyerhardt, J.A. Effects of Exercise or Metformin on Myokine Concentrations in Patients with Breast and Colorectal Cancer: A Phase II Multi-Centre Factorial Randomized Trial. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 1520–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezin, A.A.; Fushtey, I.M.; Berezin, A.E. The Effect of SGLT2 Inhibitor Dapagliflozin on Serum Levels of Apelin in T2DM Patients with Heart Failure. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezina, T.A.; Fushtey, I.M.; Berezin, A.A.; Pavlov, S.V.; Berezin, A.E. Predictors of Kidney Function Outcomes and Their Relation to SGLT2 Inhibitor Dapagliflozin in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Who Had Chronic Heart Failure. Adv. Ther. 2024, 41, 292–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, K.X.; Fischer, C.; Vu, J.; Gheblawi, M.; Wang, W.; Gottschalk, S.; Iturrioz, X.; Llorens-Cortés, C.; Oudit, G.Y.; Vederas, J.C. Metabolically Stable Apelin-Analogues, Incorporating Cyclohexylalanine and Homoarginine, as Potent Apelin Receptor Activators. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trân, K.; Murza, A.; Sainsily, X.; Coquerel, D.; Côté, J.; Belleville, K.; Haroune, L.; Longpré, J.-M.; Dumaine, R.; Salvail, D.; et al. A Systematic Exploration of Macrocyclization in Apelin-13: Impact on Binding, Signaling, Stability, and Cardiovascular Effects. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 2266–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, C.; Lamer, T.; Fernandez, K.; Gheblawi, M.; Wang, W.; Pascoe, C.; Lambkin, G.; Iturrioz, X.; Llorens-Cortes, C.; Oudit, G.Y.; et al. Optimizing PEG-Extended Apelin Analogues as Cardioprotective Drug Leads: Importance of the KFRR Motif and Aromatic Head Group for Improved Physiological Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 12073–12082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, C.; Nyimanu, D.; Yang, P.; Kuc, R.E.; Williams, T.L.; Fitzpatrick, C.M.; Foster, R.; Glen, R.C.; Maguire, J.J.; Davenport, A.P. The G Protein Biased Small Molecule Apelin Agonist CMF-019 Is Disease Modifying in Endothelial Cell Apoptosis In Vitro and Induces Vasodilatation Without Desensitisation In Vivo. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 588669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brame, A.L.; Maguire, J.J.; Yang, P.; Dyson, A.; Torella, R.; Cheriyan, J.; Singer, M.; Glen, R.C.; Wilkinson, I.B.; Davenport, A.P. Design, Characterization, and First-In-Human Study of the Vascular Actions of a Novel Biased Apelin Receptor Agonist. Hypertension 2015, 65, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, J.; Kimura, J.; Ishida, J.; Kohda, T.; Morishita, S.; Ichihara, S.; Fukamizu, A. Evaluation of Novel Cyclic Analogues of Apelin. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2008, 22, 547–552. [Google Scholar]

- Iturrioz, X.; Alvear-Perez, R.; De Mota, N.; Franchet, C.; Guillier, F.; Leroux, V.; Dabire, H.; Le Jouan, M.; Chabane, H.; Gerbier, R.; et al. Identification and Pharmacological Properties of E339–3D6, the First Nonpeptidic Apelin Receptor Agonist. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 1506–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, P.; Maloney, P.R.; Hedrick, M.; Gosalia, P.; Milewski, M.; Li, L.; Roth, G.P.; Sergienko, E.; Suyama, E.; Sugarman, E.; et al. Probe Report Title: Functional Agonists of the Apelin J (APJ) Receptor; NIH: Bethesda, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ason, B.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Q.; Hoagland, K.M.; Chui, R.W.; Fielden, M.; Sutherland, W.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Y.; Mihardja, S.; et al. Cardiovascular Response to Small-Molecule APJ Activation. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 5, 132898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, C.; Nyimanu, D.; Williams, T.L.; Huggins, D.J.; Sulentic, P.; Macrae, R.G.C.; Yang, P.; Glen, R.C.; Maguire, J.J.; Davenport, A.P. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. CVII. Structure and Pharmacology of the Apelin Receptor with a Recommendation That Elabela/Toddler Is a Second Endogenous Peptide Ligand. Pharmacol. Rev. 2019, 71, 467–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowes, J.; Brown, A.J.; Hamon, J.; Jarolimek, W.; Sridhar, A.; Waldron, G.; Whitebread, S. Reducing Safety-Related Drug Attrition: The Use of in Vitro Pharmacological Profiling. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macaluso, N.J.M.; Pitkin, S.L.; Maguire, J.J.; Davenport, A.P.; Glen, R.C. Discovery of a Competitive Apelin Receptor (APJ) Antagonist. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, N.; Fang, J.; Acheampong, E.; Mukhtar, M.; Pomerantz, R.J. Binding of ALX40-4C to APJ, a CNS-Based Receptor, Inhibits Its Utilization as a Co-Receptor by HIV-1. Virology 2003, 312, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Gonidec, S.; Chaves-Almagro, C.; Bai, Y.; Kang, H.J.; Smith, A.; Wanecq, E.; Huang, X.; Prats, H.; Knibiehler, B.; Roth, B.L.; et al. Protamine Is an Antagonist of Apelin Receptor, and Its Activity Is Reversed by Heparin. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 2507–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, P.R.; Khan, P.; Hedrick, M.; Gosalia, P.; Milewski, M.; Li, L.; Roth, G.P.; Sergienko, E.; Suyama, E.; Sugarman, E.; et al. Discovery of 4-Oxo-6-((Pyrimidin-2-Ylthio)Methyl)-4H-Pyran-3-Yl 4-Nitrobenzoate (ML221) as a Functional Antagonist of the Apelin (APJ) Receptor. Bioorg Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 6656–6660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAnally, D.; Siddiquee, K.; Gomaa, A.; Szabo, A.; Vasile, S.; Maloney, P.R.; Divlianska, D.B.; Peddibhotla, S.; Morfa, C.J.; Hershberger, P.; et al. Repurposing Antimalarial Aminoquinolines and Related Compounds for Treatment of Retinal Neovascularization. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, Y.; Sharma, R. The Role of Apelin in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1683865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berta, J.; Kenessey, I.; Dobos, J.; Tovari, J.; Klepetko, W.; Jan Ankersmit, H.; Hegedus, B.; Renyi-Vamos, F.; Varga, J.; Lorincz, Z.; et al. Apelin Expression in Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Role in Angiogenesis and Prognosis. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010, 5, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, A.; Kälin, S.; Monk, R.; Radke, J.; Heppner, F.L.; Kälin, R.E. Apelin Controls Angiogenesis-Dependent Glioblastoma Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Hayashi, Y.; Kidoya, H.; Takakura, N. Endothelial Cell-Derived Apelin Inhibits Tumor Growth by Altering Immune Cell Localization. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ligand | Action | Binding Affinity | Units | Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYCLO APELIN-12 (1–12) | Full agonist | 6.3 | pEC50 | Inhibit cAMP accumulation, increase Akt and ERK phosphorylation | Hamada et al., 2008 [87] |

| COMPOUND 15/ANALOG 15 | Full agonist | 0.15 | Ki | Activate Gαi1 and recruit β-arrestin2 | Trân et al., 2018 [83] |

| PEG-17A2 | Full agonist | 6.3 | EC50 | Calcium release, lower blood pressure | Fischer et al., 2020 [84] |

| E339-3D6 | Agonist | 6.4 | pKi | Vasorelaxation, reduce vasopressin release | Iturrioz et al., 2010 [88] |

| ML-233 | Full agonist | 3.7 | EC50 | Reduce cAMP, increase APJ internalization | Khan et al., 2011 [89] |

| CMF-019 | Full agonist | 8.58 | pKi | Prevent apoptosis, reduce artery pressure, increase cardiac contractility | Read et al., 2021 [85] |

| MM07 | Full agonist | 9.5 | pEC50 | Increase cardiac output (rat) and forearm blood flow (human) | Brame et al., 2015 [86] |

| AMG986 | Agonist | 9.5 | pEC50 | Increase stroke volume, ejection fraction, and heart rate; decrease cardiac afterload | Ason et al., 2020 [90] |

| BMS-986224 | Agonist | 9.5 | pKd | Increase stroke volume and cardiac output; decrease arterial pressure | Gargalovic et al., 2021 [62] |

| Ligand | Action | Binding Affinity | Units | Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM54 | Antagonist | 8.2 | pKi | Inhibit cAMP accumulation | Macaluso et al., 2011 [93] |

| ALX40-4C | Antagonist | 5.5 | pIC50 | Block cell membrane fusion | Zhou et al., 2003 [94] |

| PROTAMINE | Antagonist | 6.4 | pKi | Antagonize G-protein- and β-arrestin-dependent pathways | Le Gonidec, et al. [95] |

| ML221 | Antagonist | 0.70 | pIC50 | Inhibit cAMP production and β-arrestin recruitment | Maloney et al., 2012 [96] |

| 4-AMINOQUINOLINE | Selective antagonist | 0.556 | pIC50 | Suppress endothelial tube formation and neovascularization | McAnally et al., 2018 [97] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Saladich-Cavallé, S.; Núñez-Delgado, S.; Huo, L.; Pons-Pellicer, F.; Martínez-Díaz, I.; Jacobs-Cachá, C.; Bermejo, S.; Vilardell-Vilà, J.; Soler, M.J. The Apelinergic System in Kidney Disease: Novel Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010111

Saladich-Cavallé S, Núñez-Delgado S, Huo L, Pons-Pellicer F, Martínez-Díaz I, Jacobs-Cachá C, Bermejo S, Vilardell-Vilà J, Soler MJ. The Apelinergic System in Kidney Disease: Novel Perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010111

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaladich-Cavallé, Sara, Sara Núñez-Delgado, Linhui Huo, Frederic Pons-Pellicer, Irene Martínez-Díaz, Conxita Jacobs-Cachá, Sheila Bermejo, Jordi Vilardell-Vilà, and Maria José Soler. 2026. "The Apelinergic System in Kidney Disease: Novel Perspectives" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010111

APA StyleSaladich-Cavallé, S., Núñez-Delgado, S., Huo, L., Pons-Pellicer, F., Martínez-Díaz, I., Jacobs-Cachá, C., Bermejo, S., Vilardell-Vilà, J., & Soler, M. J. (2026). The Apelinergic System in Kidney Disease: Novel Perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010111