Assessment of the Effect of Phosphorus in the Structure of Epoxy Resin Synthesized from Natural Phenol–Eugenol on Thermal Resistance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.2. TGA with FTIR

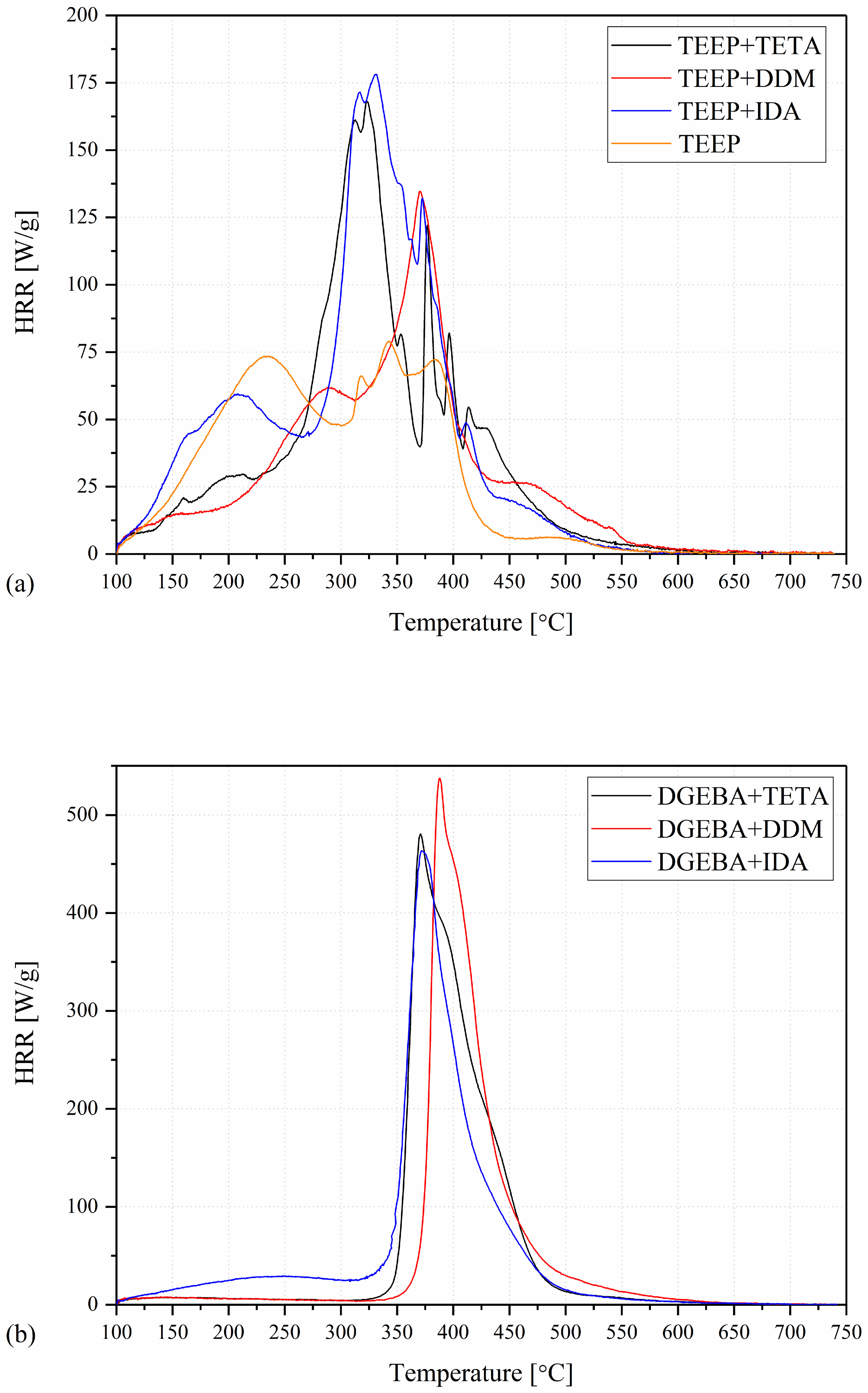

2.3. Pyrolysis and Combustion Flow Calorimeter (PCFC)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

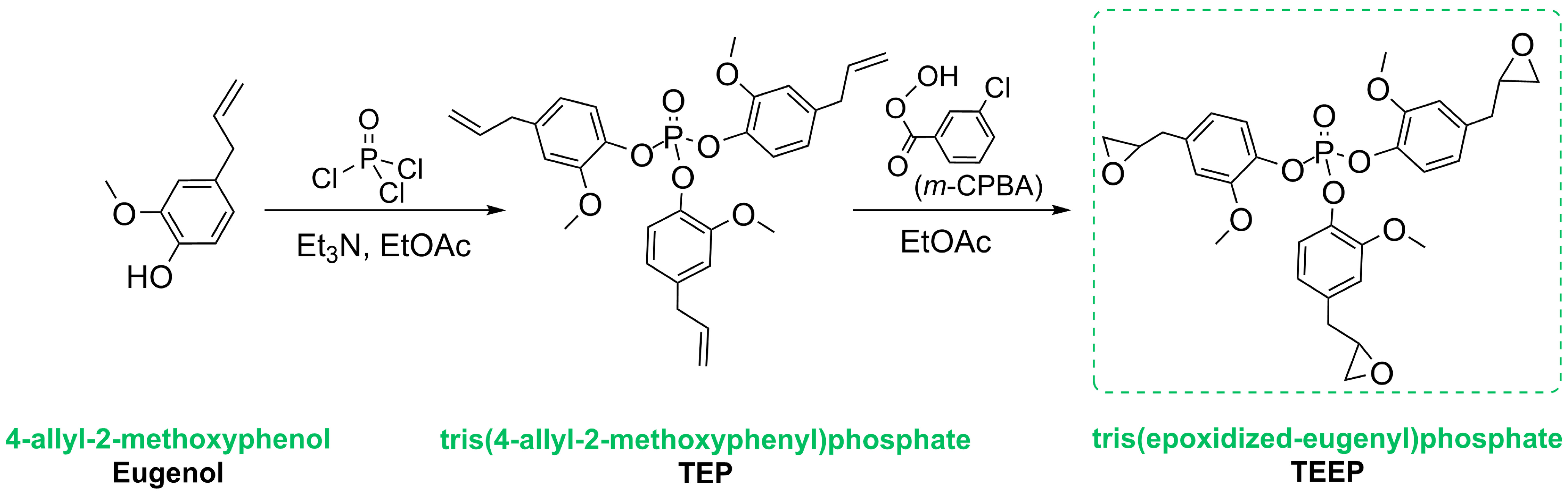

3.2. Synthetic Route to Obtain Tris(2-Methoxy-4-(2,3-Epoxypropyl)Phenyl Phosphate) (TEEP)

3.3. Sample Preparation

3.4. Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhi, M.; Yang, X.; Fan, R.; Yue, S.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Q.; He, Y. A Comprehensive Review of Reactive Flame-Retardant Epoxy Resin: Fundamentals, Recent Developments, and Perspectives. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 201, 109976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, H.; Senanayake, R.B.; Nunna, S.; Zhang, J.; Basnayake, A.P.; Heitzmann, M.T.; Varley, R.J. A DOPO-Eugenol Linear Siloxane as a Highly Effective Liquid Flame Retardant Also Imparting Improved Mechanical Properties to an Epoxy Amine Network. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan Hoang, A.; Viet Pham, V. 2-Methylfuran (MF) as a Potential Biofuel: A Thorough Review on the Production Pathway from Biomass, Combustion Progress, and Application in Engines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 148, 111265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P.; Yi, D.; Hao, J.; Ye, X.; Gao, M.; Song, T. Fabrication of Melamine Trimetaphosphate 2D Supermolecule and Its Superior Performance on Flame Retardancy, Mechanical and Dielectric Properties of Epoxy Resin. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 225, 109269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Qin, J.; He, J. Preparation of Intercalated Organic Montmorillonite DOPO-MMT by Melting Method and Its Effect on Flame Retardancy to Epoxy Resin. Polymers 2021, 13, 3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, S.; Zhou, Z.; Jiang, J.; Sai, T.; Ran, S.; Fang, Z.; Song, P.; Wang, H. Flame-Retardant, Transparent, Mechanically-Strong and Tough Epoxy Resin Enabled by High-Efficiency Multifunctional Boron-Based Polyphosphonamide. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 131578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, S.; Song, P.; Yu, B.; Ran, S.; Chevali, V.S.; Liu, L.; Fang, Z.; Wang, H. Phosphorus-Containing Flame Retardant Epoxy Thermosets: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2021, 114, 101366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Song, L.; Bihe, Y.; Yu, B.; Shi, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yuen, R.K.K. Organic/Inorganic Flame Retardants Containing Phosphorus, Nitrogen and Silicon: Preparation and Their Performance on the Flame Retardancy of Epoxy Resins as a Novel Intumescent Flame Retardant System. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2014, 143, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.-H.; Li, X.-L.; Shi, H.; Liu, Q.-Y.; Xie, W.-M.; Wu, S.-J.; Zhao, N.; Wang, D.-Y. Insight into the Flame-Retardant Mechanism of Different Organic-Modified Layered Double Hydroxide for Epoxy Resin. Appl. Clay Sci. 2024, 248, 107233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, T.; Wang, C. Synergistic Effect of a Phosphorus–Nitrogen Flame Retardant on Engineering Plastics. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 92, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passauer, L. Thermal Characterization of Ammonium Starch Phosphate Carbamates for Potential Applications as Bio-Based Flame-Retardants. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 211, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, S.; Guo, W.-W.; Wang, P.-L.; Xing, W.; Song, L.; Hu, Y. Renewable Cardanol-Based Phosphate as a Flame Retardant Toughening Agent for Epoxy Resins. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 3409–3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebke, S.; Thümmler, K.; Sonnier, R.; Tech, S.; Wagenführ, A.; Fischer, S. Suitability and Modification of Different Renewable Materials as Feedstock for Sustainable Flame Retardants. Molecules 2020, 25, 5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, L.D.; Capricho, J.C.; Peerzada, M.; Salim, N.V.; Parameswaranpillai, J.; Hameed, N. Recent Progress and Multifunctional Applications of Fire-Retardant Epoxy Resins. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xie, Q.; Lin, J.; Huang, J.; Xie, K.; Liu, J.; Li, X.; Wei, W. A Phosphorus/Silicon-containing Flame Retardant Based on Eugenol for Improving Flame Retardancy and Smoke Suppression of Epoxy Resin. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e54474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Qian, L.; Feng, H.; Jin, S.; Hao, J. Toughening Effect and Flame-Retardant Behaviors of Phosphaphenanthrene/Phenylsiloxane Bigroup Macromolecules in Epoxy Thermoset. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 9992–10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecochard, Y.; Decostanzi, M.; Negrell, C.; Sonnier, R.; Caillol, S. Cardanol and Eugenol Based Flame Retardant Epoxy Monomers for Thermostable Networks. Molecules 2019, 24, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; He, Z.; Wu, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, C.; Lei, C. Synthesis of a Novel Nonflammable Eugenol-Based Phosphazene Epoxy Resin with Unique Burned Intumescent Char. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 390, 124620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Zhang, T.; Li, J.; Tan, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, X. Facile Synthesis of Eugenol-Based Phosphorus/Silicon-Containing Flame Retardant and Its Performance on Fire Retardancy of Epoxy Resin. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 1794–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhou, W.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, S.; Yang, W.; Ma, P. Preparation and Properties of Eugenol Based Flame-Retarding Epoxy Resin. React. Funct. Polym. 2024, 201, 105940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Duan, H.; Zou, J.; Zhang, J.; Ma, H. A Bio-Based Phosphorus-Containing Co-Curing Agent towards Excellent Flame Retardance and Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Resin. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2021, 187, 109548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Dai, J.; Wang, S.; Peng, Y.; Cao, L.; Liu, X. Facile Synthesis of Bio-Based Reactive Flame Retardant from Vanillin and Guaiacol for Epoxy Resin. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 190, 107926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Zhang, P.; Song, Z.; Guo, F.; Hua, Z.; You, T.; Li, S.; Cui, C.; Liu, L. Preparation of Eugenol-Based Flame Retardant Epoxy Resin with an Ultrahigh Glass Transition Temperature via a Dual-Curing Mechanism. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2025, 231, 111092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Hou, Y.; Hu, Y.; Hu, W. Effect of Additive Phosphorus-Nitrogen Containing Flame Retardant on Char Formation and Flame Retardancy of Epoxy Resin. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018, 214, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, X. Synthesis, Characterization, Thermal Properties and Flame Retardancy of a Novel Nonflammable Phosphazene-Based Epoxy Resin. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2009, 94, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, J.; Peng, H.; Liao, J.; Wang, X. Synthesis of a Novel PEPA-Substituted Polyphosphoramide with High Char Residues and Its Performance as an Intumescent Flame Retardant for Epoxy Resins. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 118, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Das, O.; Zhao, S.-N.; Sun, T.-S.; Xu, Q.; Jiang, L. Pyrolysis Kinetic Study and Reaction Mechanism of Epoxy Glass Fiber Reinforced Plastic by Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TG) and TG–FTIR (Fourier-Transform Infrared) Techniques. Polymers 2020, 12, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kök, M.V.; Varfolomeev, M.A.; Nurgaliev, D.K. Crude Oil Characterization Using TGA-DTA, TGA-FTIR and TGA-MS Techniques. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 154, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B.; Kandola, B.K.; Horrocks, A.R.; Price, D. A Quantitative Study of Carbon Monoxide and Carbon Dioxide Evolution during Thermal Degradation of Flame Retarded Epoxy Resins. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2007, 92, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, S.; Wang, S.; Xia, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, J.; Guo, Z.; Fang, Z.; Li, J. Roles of Multi-Hierarchical Char in Flame Retardancy for Epoxy Composites Induced by Modified Thermal Conductive Fillers and Flame-Retardant Assembly. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 292, 112092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lv, C.; Shen, R.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Q. Comparison of Thermal and Fire Properties of Carbon/Epoxy Laminate Composites Manufactured Using Two Forming Processes. Polym. Compos. 2020, 41, 3778–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard, R.; Negrell, C.; Fache, M.; Ferry, L.; Sonnier, R.; David, G. From a Bio-Based Phosphorus-Containing Epoxy Monomer to Fully Bio-Based Flame-Retardant Thermosets. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 70856–70867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battig, A.; Müller, P.; Bertin, A.; Schartel, B. Hyperbranched Rigid Aromatic Phosphorus—Containing Flame Retardants for Epoxy Resins. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2021, 306, 2000731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ma, S.; Xu, C.; Liu, Y.; Dai, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Shen, X.; Wei, J.; et al. Vanillin-Derived High-Performance Flame Retardant Epoxy Resins: Facile Synthesis and Properties. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 1892–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, M.; Jiang, L. Bio–Resourced Eugenol Derived Phthalonitrile Resin for High Temperature Composite. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 50721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Krevelen, D. Some Basic Aspects of Flame Resistance of Polymeric Materials. Polymer 1975, 16, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visakh, P.M.; Nazarenko, O.B.; Amelkovich, Y.A.; Melnikova, T.V. Effect of Zeolite and Boric Acid on Epoxy-Based Composites. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2016, 27, 1098–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liang, G.; Gu, A.; Yuan, L. Flame Retardancy and Mechanism of Bismaleimide Resins Based on a Unique Inorganic–Organic Hybridized Intumescent Flame Retardant. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 15075–15087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babrauskas, V.; Peacock, R.D. Heat Release Rate: The Single Most Important Variable in Fire Hazard. Fire Saf. J. 1992, 18, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouritz, A.P.; Mathys, Z.; Gibson, A.G. Heat Release of Polymer Composites in Fire. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2006, 37, 1040–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, M.H.; Dashtizadeh, A.; Motamedoshariati, H.; Soury, H. A Simple Model for Reliable Prediction of the Specific Heat Release Capacity of Polymers as an Important Characteristic of Their Flammability. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 128, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Agumba, D.O.; Pham, D.H.; Kim, H.C.; Kim, J. Recent Progress in Bio—Based Eugenol Resins: From Synthetic Strategies to Structural Properties and Coating Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faye, I.; Decostanzi, M.; Ecochard, Y.; Caillol, S. Eugenol Bio-Based Epoxy Thermosets: From Cloves to Applied Materials. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 5236–5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matykiewicz, D.; Dudziec, B. Curing and Degradation Kinetics of Phosphorus-Modified Eugenol-Based Epoxy Resin. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 4353–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | T5% (°C) | T10% (°C) | Residual Mass (%) | DTG Peak (°C)/max. Rate (%/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEEP+TETA | 224.5 | 271.6 | 9.47 | 338.7/6.1 |

| TEEP+DDM | 216.8 | 258.2 | 16.33 | 350.7/3.1 |

| TEEP+IDA | 178.2 | 264.6 | 9.61 | 304.7/5.3 |

| DGEBA+ TETA | 343.4 | 352.6 | 0.41 | 336.1/12.8 |

| Name | pcHRR (W/g) | TpcHRR (°C) | THR (kJ/g) | HRC (J/g∙K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEEP | 59.7 ± 2.9 | 205 ± 8 | 17.2 ± 0.5 | 84 ± 3 |

| TEEP+TETA | 165.3 ± 7 | 317 ± 5 | 20.6 ± 0.7 | 182 ± 5 |

| TEEP+DDM | 132.2 ± 4.1 | 369 ± 2 | 17.5 ± 0.3 | 144 ± 4 |

| TEEP+IDA | 185 ± 20.0 | 320 ± 5 | 24.0 ± 0.7 | 203 ± 9 |

| DGEBA+TETA | 461.5 ± 34.1 | 373 ± 2 | 31.5 ± 1.4 | 501 ± 32 |

| DGEBA+DDM | 548.5 ± 22.5 | 391 ± 2 | 29.6 ± 0.2 | 597 ± 29 |

| DGEBA+IDA | 461.4 ± 24.4 | 373 ± 2 | 32.1 ± 1.3 | 518 ± 32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Matykiewicz, D.; Dudziec, B.; Piasecki, A. Assessment of the Effect of Phosphorus in the Structure of Epoxy Resin Synthesized from Natural Phenol–Eugenol on Thermal Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010112

Matykiewicz D, Dudziec B, Piasecki A. Assessment of the Effect of Phosphorus in the Structure of Epoxy Resin Synthesized from Natural Phenol–Eugenol on Thermal Resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010112

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatykiewicz, Danuta, Beata Dudziec, and Adam Piasecki. 2026. "Assessment of the Effect of Phosphorus in the Structure of Epoxy Resin Synthesized from Natural Phenol–Eugenol on Thermal Resistance" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010112

APA StyleMatykiewicz, D., Dudziec, B., & Piasecki, A. (2026). Assessment of the Effect of Phosphorus in the Structure of Epoxy Resin Synthesized from Natural Phenol–Eugenol on Thermal Resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010112