Current Controversies on Adequate Circulating Vitamin D Levels in CKD

Abstract

1. Introduction

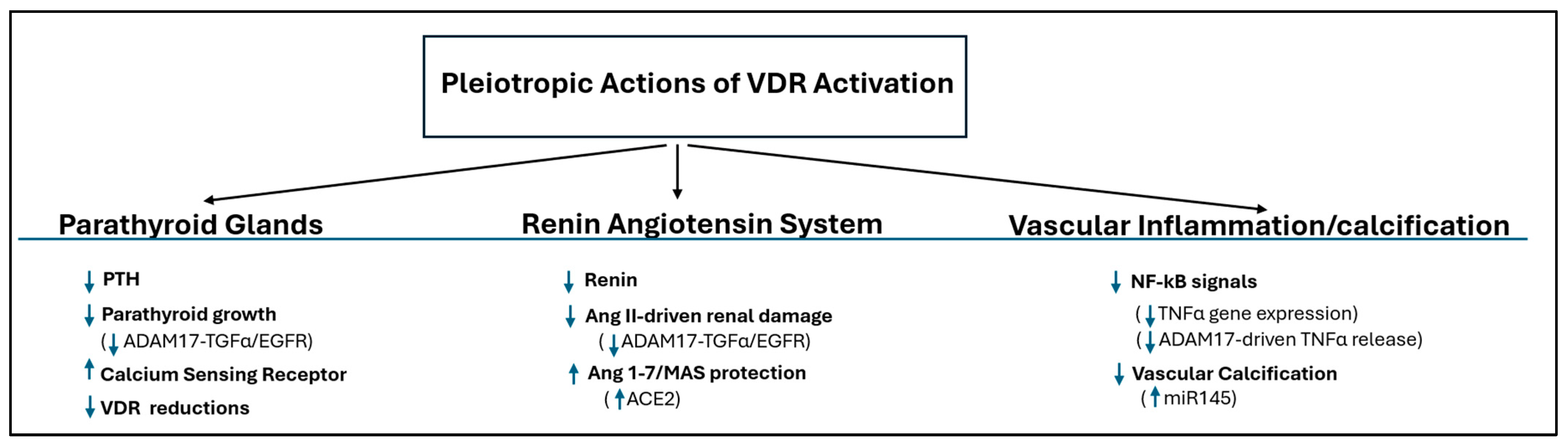

2. Paradigm Shift 1: From Simple 1,25(OH)2D Replacement to Selective VDR Activation

2.1. Pathophysiological Discoveries and Impact on CKD Progression

2.1.1. Parathyroid Glands

- (a)

- Direct Gene Suppression: The active vitamin D/Vitamin D Receptor (VDR) complex directly suppresses the transcription of the PTH gene, a foundational mechanism of control [9].

- (b)

- Sensitization to Calcium: Active vitamin D is crucial for maintaining the parathyroid’s sensitivity to calcium. It achieves this by upregulating the expression of the Calcium-Sensing Receptor (CaSR) [10,11,12]. In CKD, a lack of adequate active vitamin D leads to fewer CaSRs, making the gland resistant to PTH suppression by calcium. This is particularly important because the CaSR also functions as a phosphate sensor [13]; high phosphate levels in CKD inhibit the CaSR activity, further stimulating PTH secretion. By increasing CaSR expression, active vitamin D helps counteract this phosphate-driven stimulation.

- (c)

- Inhibition of Parathyroid Growth: Uncontrolled SHPT results from parathyroid hyperplasia. This overgrowth is driven by increases in cyclooxygenase2-prostaglandin E2 and mTOR [14], and also by a powerful autocrine growth loop involving Transforming Growth Factor-alpha (TGF-α) and its receptor, EGFR, which is potently exacerbated by the hyperphosphatemia of advanced CKD [7,15]. The active vitamin D/VDR complex directly counters this vicious cycle at its source by suppressing ADAM17 [16], the enzyme that initiates the loop through the release of TGF-α from the parathyroid cell surface.

- (d)

- Parathyroid Desensitization to VDR Actions: Critically, this enhanced ADAM17/TGF-α/EGFR axis does more than just stimulate growth; it is also the primary driver of vitamin D resistance in CKD. It achieves this by decreasing the cellular C/EBPβ/LIP ratio, which in turn leads to a marked suppression of the VDR gene itself, the cause of resistance to active vitamin D therapy in advanced CKD [7]. Therefore, by inhibiting the dominant, phosphate-driven ADAM17/TGF-α/EGFR loop, active vitamin D simultaneously controls parathyroid cell proliferation and preserves the gland’s essential sensitivity to active vitamin D. However, the pathological importance of the C/EBPβ mechanism extends beyond the parathyroid gland, driving systemic functional vitamin D deficiency. Evidence for this link comes from models demonstrating that inflammatory challenges (e.g., LPS stimulation) promote LIP synthesis [20], which then directly suppresses the VDR gene. Furthermore, LIP accumulation has been implicated in favoring ER stress-driven apoptosis [20]—a critical pathway for non-skeletal damage (e.g., vascular calcification propensity) in the CKD milieu [21].

2.1.2. Bone

2.1.3. Systemic Protection

- (a)

- Control of the Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System (RAAS)

- (b)

- Renal and Vascular Protection:

- (c)

- Anti-Inflammatory Effects:

2.2. Therapeutic Implications and Recommendations

The Active Vitamin D Therapeutic Paradox: From Promising Mechanistic Endpoints to Failed Outcome Trials

3. Paradigm Shift 2: The Rise in Nutritional Vitamin D and Systemic Health

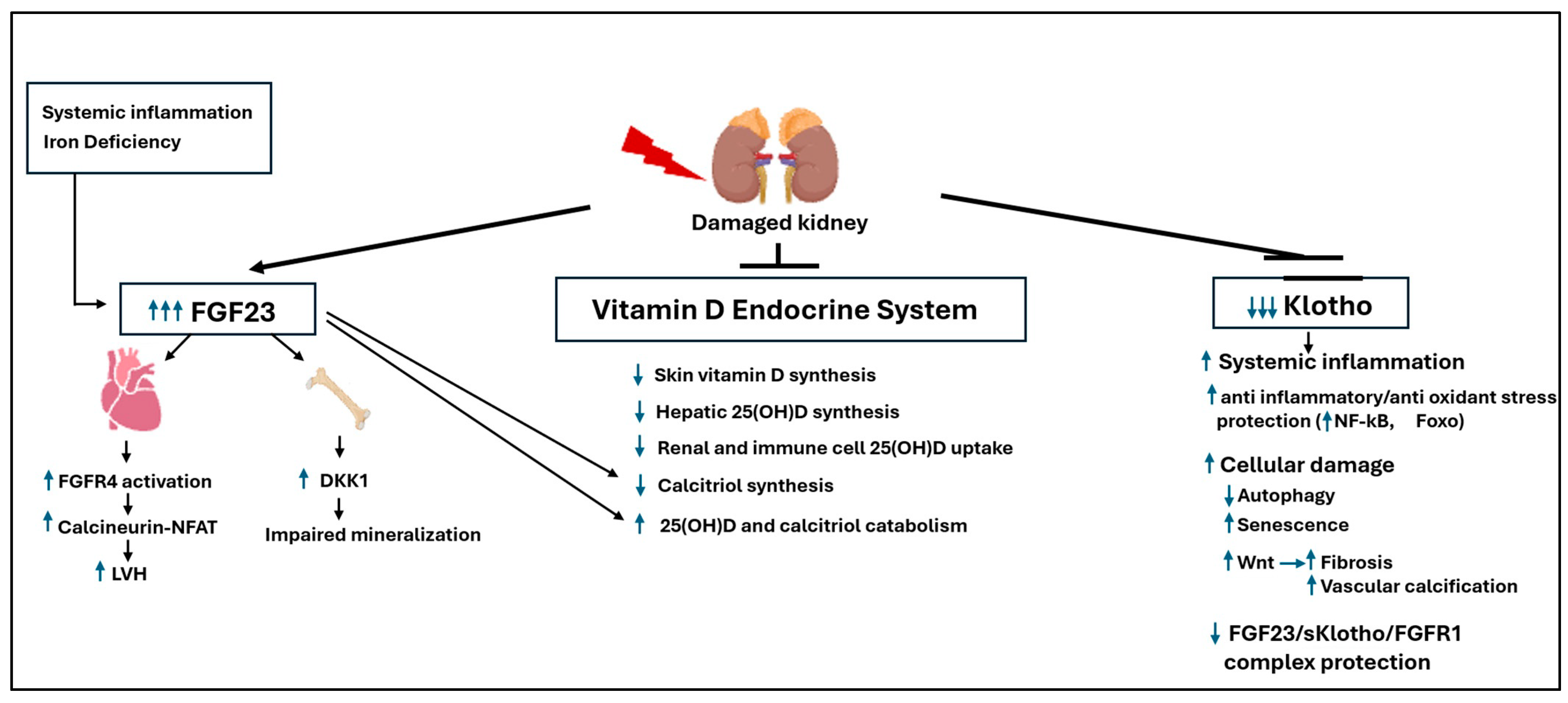

3.1. Pathophysiological Discoveries and Impact on CKD Progression

- (a)

- Impaired Initial Synthesis (Skin and Liver): CKD contributes to lower overall vitamin D levels by reducing the cutaneous synthesis of cholecalciferol (Vitamin D3) in the skin [52], which can be exacerbated by factors such as azotemia or limited sun exposure. Furthermore, there is evidence that CKD leads to abnormal hepatic conversion of cholecalciferol to 25(OH)D (25-hydroxylation), impairing the essential first step of metabolic activation.

- (b)

- Loss of Renal 25(OH)D Recycling (Megalin Failure): A critical early event in CKD is the loss of the endocytosis receptor megalin in the proximal tubules [53]. Megalin is essential for reabsorbing the filtered 25(OH)D bound to its vitamin D binding protein (DBP) [54]. Its failure has a dual consequence: it reduces the substrate available for renal calcitriol synthesis and, just as importantly, prevents the recycling of 25(OH)D back into circulation. This systemic loss of substrate starves the rest of the body’s tissues of the 25(OH)D they need, crippling their ability to perform local calcitriol synthesis and compromising the protective effects of autocrine/paracrine VDR activation.

- (c)

- Impaired Extrarenal 25(OH)D Uptake: The problem of 25(OH)D deficiency in CKD extends beyond defective renal recycling; extrarenal tissues also show a marked defect in their ability to take up the prohormone. Immune cells from dialysis patients, for example, demonstrate this impaired uptake [55]. This suggests that even if circulating 25(OH)D levels are adequate, the tissues that depend on it for local calcitriol synthesis cannot access it, thereby crippling the protective autocrine/paracrine benefits of VDR activation essential for slowing CKD progression. The critical importance of these extrarenal pathways is underscored by findings in anephric individuals: they retain the ability to produce significant amounts of calcitriol, and can even normalize circulating levels, provided they are given sufficient 25(OH)D [56].

- (d)

- Therapy-Induced Catabolism: Paradoxically, the high doses of active vitamin D/analogs used to treat SHPT can worsen nutritional vitamin D deficiency. These drugs potently induce CYP24A1 [57], the enzyme that degrades both active vitamin D and its precursor, 25(OH)D. This creates a vicious cycle where the treatment for one aspect of the disease exacerbates the underlying systemic deficiency.

3.2. Therapeutic Implications and Recommendations

3.2.1. Current Controversies in Correcting Vitamin D Deficiency

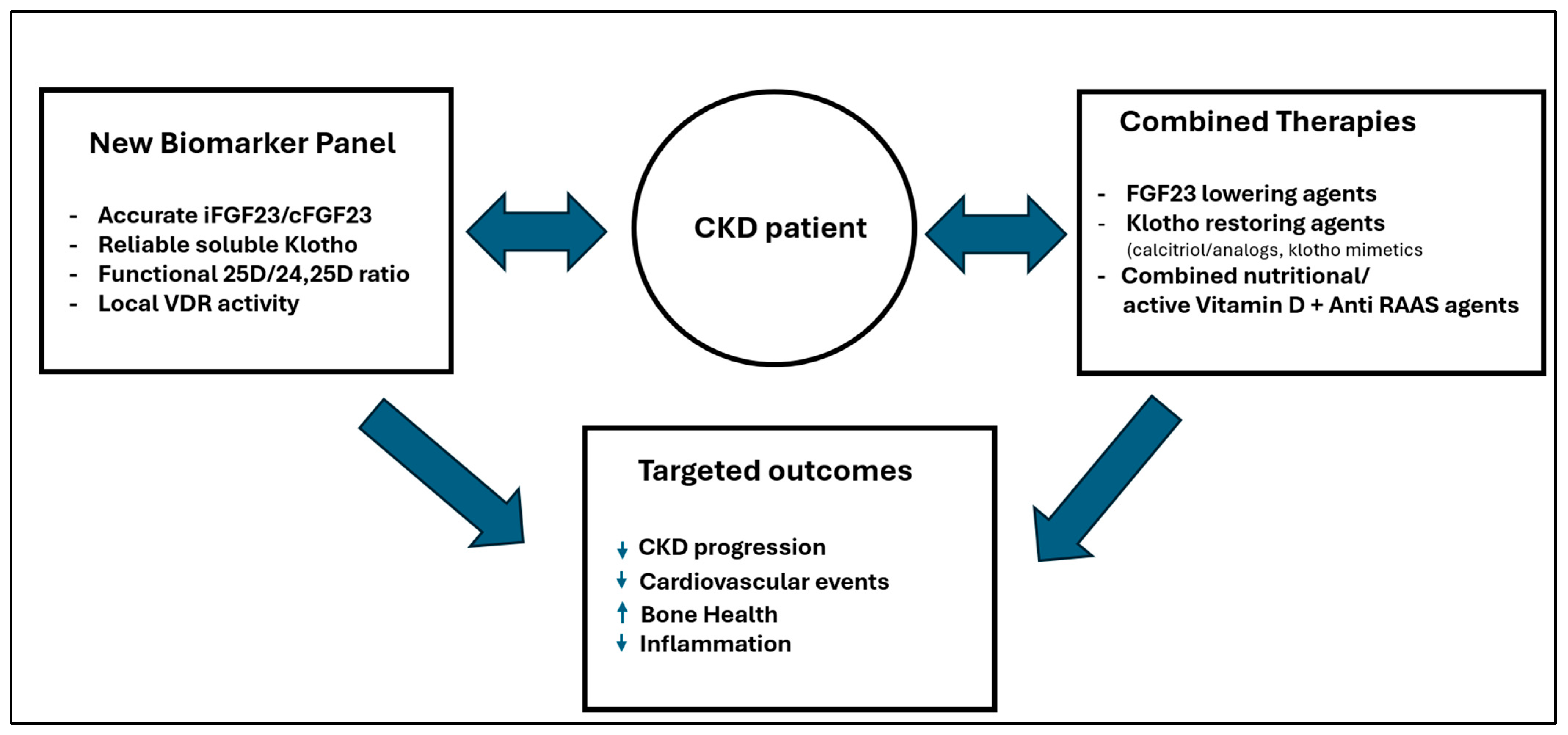

3.2.2. The Biomarker Challenge: What Are We Really Measuring?

- (a)

- Inaccurate Assays and Catabolism: Most clinical labs use assays that cannot distinguish 25(OH)D from its major catabolite, 24,25(OH)2D, leading to an overestimation of a patient’s true vitamin D level. A more accurate functional marker—the ratio of 25(OH)D to 24,25(OH)2D—can reveal the rate of vitamin D degradation, but measuring this requires liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, which is not widely available. Table 1 compares standard immunoassays and the gold standard LC-MS/MS for measurements of vitamin D metabolites.

- (b)

- The “Local Conversion” Blind Spot: Perhaps the most significant limitation is that measuring circulating 25(OH)D completely ignores local, tissue-specific vitamin D metabolism [62]. For instance, tissues like the parathyroid gland can convert cholecalciferol directly to 25(OH)D for their own use [63]. This crucial local activation does not raise systemic 25(OH)D levels and is therefore invisible to our current blood tests, yet it may be essential for local, protective VDR signaling.

3.2.3. The Dosing Paradox and Choice of Agent

- (a)

- Cholecalciferol (D3) and Ergocalciferol (D2): These are the most common nutritional vitamin D supplements. They are inexpensive and rely on hepatic 25-hydroxylation to raise serum 25(OH)D, with the goal of achieving a normal vitamin D status (>30 ng/mL). When administered in daily doses (typically up to 4000 IU), both forms are considered equally effective [67,68]. However, their pharmacokinetics differ significantly with high-dose, intermittent (bolus) administration. Ergocalciferol (D2) has a shorter circulating half-life than cholecalciferol (D3) [69]. This is primarily because its metabolite, 25(OH)D2, has a lower binding affinity for the Vitamin D Binding Protein (DBP) compared to 25(OH)D3. This weaker binding leads to faster metabolic clearance, making bolus D2 dosing less efficacious. While overall DBP concentration and genotype do influence the half-life of all vitamin D metabolites [70], this fundamental difference in affinity is the key reason for D2’s shorter duration in circulation. Furthermore, while high intermittent (bolus) doses are often prescribed to ensure patient compliance, this practice is generally discouraged for two key reasons. First, it carries a risk of potential toxicity, such as transient hypercalcemia. Second, as demonstrated by the work of Armas and co-workers, the hepatic conversion to 25(OH)D is inefficient at high single doses [48]. Their findings indicate that the 25-hydroxylation pathway becomes saturated at intakes that exceed approximately 4000 IU, limiting the effective yield of 25(OH)D from a large bolus.

- (b)

- Calcifediol (25(OH)D): Available as standard or extended-release (ER) formulations, calcifediol offers a direct path to raise serum 25(OH)D by bypassing liver activation. Its potency is a key distinction; unlike nutritional vitamin D, calcifediol can directly bind to and activate the VDR [71]. This direct VDR activation, however, increases the risks of hypercalcemia, accelerated catabolism, and the induction of FGF23 (a topic central to Paradigm Shift 3). In stark contrast, clinical trials with the more costly ER-Calcifediol have shown it can effectively raise circulating 25(OH)D and suppress PTH at very high 25(OH)D concentrations [72,73] and also increase serum calcitriol and maintain but not suppress serum PTH [74,75], while avoiding significant elevations in serum FGF23, calcium, or phosphate, presenting it as a potentially safer therapeutic option.

- (c)

- The Obesity Factor: A major confounding variable in dosing is obesity. Because vitamin D is fat-soluble, it becomes trapped or sequestered in adipose tissue (Reviewed in [76]). This leads to lower circulating 25(OH)D levels for a given dose, effectively limiting the substrate available for local activation to calcitriol and VDR pleiotropic protective actions in key targets like the cardiovascular system. This is a critical consideration in managing patients with type 2 diabetes and diabetic nephropathy, who are frequently obese and at the highest risk for progressive renal and cardiovascular damage.

3.2.4. A Novel Strategy: 25(OH)D and Calcitriol Synergy

3.2.5. Corollary: A Shift Toward Functional Dosing

4. Paradigm Shift 3: The FGF23-Klotho Axis as the Central Driver of Cardiovascular and Renal Risk

4.1. Pathophysiological Discoveries and Impact on CKD Progression

4.1.1. The Core Imbalance: FGF23 Resistance and Klotho Deficiency

4.1.2. The Vicious Cycle: Drivers of Pathological FGF23 Levels

4.1.3. FGF23 Toxicity: Klotho-Independent Cardiac and Skeletal Damage

4.1.4. FGF23 Toxicity: Dismantling the Vitamin D Endocrine System

4.1.5. The Role of C-Terminal FGF23 Fragments

4.1.6. The Protective Role of Klotho: A Systemic Anti-Aging Defense

4.2. Therapeutic Implications and Recommendations

4.2.1. The Dilemma (Calcimimetics vs. Vitamin D)

4.2.2. The Diagnostic Challenge

4.2.3. The Call to Action

4.2.4. Precision Medicine and Vitamin D in CKD

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ortiz, A.; Covic, A.; Fliser, D.; Fouque, D.; Goldsmith, D.; Kanbay, M.; Mallamaci, F.; Massy, Z.A.; Rossignol, P.; Vanholder, R.; et al. Epidemiology, contributors to, and clinical trials of mortality risk in chronic kidney failure. Lancet 2014, 383, 1831–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- London, G.M.; Guerin, A.P.; Marchais, S.J.; Metivier, F.; Pannier, B.; Adda, H. Arterial media calcification in end-stage renal disease: Impact on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2003, 18, 1731–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronco, C.; Cozzolino, M. Mineral metabolism abnormalities and vitamin D receptor activation in cardiorenal syndromes. Heart Fail. Rev. 2012, 17, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, D.E.; Fraser, D.R.; Kodicek, E.; Morris, H.R.; Williams, D.H. Identification of 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, a new kidney hormone controlling calcium metabolism. Nature 1971, 230, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slatopolsky, E.; Weerts, C.; Thielan, J.; Horst, R.; Harter, H.; Martin, K.J. Marked suppression of secondary hyperparathyroidism by intravenous administration of 1,25-dihydroxy-cholecalciferol in uremic patients. J. Clin. Investig. 1984, 74, 2136–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, N.; Tanaka, H.; Tominaga, Y.; Fukagawa, M.; Kurokawa, K.; Seino, Y. Decreased 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor density is associated with a more severe form of parathyroid hyperplasia in chronic uremic patients. J. Clin. Investig. 1993, 92, 1436–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, M.V.; Sato, T.; Alvarez-Hernandez, D.; Yang, J.; Tokumoto, M.; Gonzalez-Suarez, I.; Lu, Y.; Tominaga, Y.; Cannata-Andia, J.; Slatopolsky, E.; et al. EGFR activation increases parathyroid hyperplasia and calcitriol resistance in kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 19, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, M.; Wolf, M.; Lowrie, E.; Ofsthun, N.; Lazarus, J.M.; Thadhani, R. Survival of patients undergoing hemodialysis with paricalcitol or calcitriol therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritter, C.S.; Armbrecht, H.J.; Slatopolsky, E.; Brown, A.J. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 suppresses PTH synthesis and secretion by bovine parathyroid cells. Kidney Int. 2006, 70, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kifor, O.; Moore, F.D., Jr.; Wang, P.; Goldstein, M.; Vassilev, P.; Kifor, I.; Hebert, S.C.; Brown, E.M. Reduced immunostaining for the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor in primary and uremic secondary hyperparathyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1996, 81, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.J.; Zhong, M.; Finch, J.; Ritter, C.; McCracken, R.; Morrissey, J.; Slatopolsky, E. Rat calcium-sensing receptor is regulated by vitamin D but not by calcium. Am. J. Physiol. 1996, 270, F454–F460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaff, L.; Hendy, G.N. Human calcium-sensing receptor gene. Vitamin D response elements in promoters P1 and P2 confer transcriptional responsiveness to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 30337–30350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centeno, P.P.; Herberger, A.; Mun, H.C.; Tu, C.; Nemeth, E.F.; Chang, W.; Conigrave, A.D.; Ward, D.T. Phosphate acts directly on the calcium-sensing receptor to stimulate parathyroid hormone secretion. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, A.; Khalaily, N.; Kilav-Levin, R.; Nechama, M.; Volovelsky, O.; Silver, J.; Naveh-Many, T. Molecular Mechanisms of Parathyroid Disorders in Chronic Kidney Disease. Metabolites 2022, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, M.V.; Yang, J.; Fernandez, E.; Dusso, A. Parathyroid-specific epidermal growth factor-receptor inactivation prevents uremia-induced parathyroid hyperplasia in mice. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, M.V.; Yang, J.; Fernandez, E.; Dusso, A. The induction of C/EBPβ contributes to vitamin D inhibition of ADAM17 expression and parathyroid hyperplasia in kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, M.; Lu, Y.; Finch, J.; Slatopolsky, E.; Dusso, A.S. p21WAF1 and TGF-α mediate parathyroid growth arrest by vitamin D and high calcium. Kidney Int. 2001, 60, 2109–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokumoto, M.; Tsuruya, K.; Fukuda, K.; Kanai, H.; Kuroki, S.; Hirakata, H. Reduced p21, p27 and vitamin D receptor in the nodular hyperplasia in patients with advanced secondary hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int. 2002, 62, 1196–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawa, S.; Nikaido, T.; Aoki, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Kumagai, T.; Furihata, K.; Fujii, S.; Kiyosawa, K. Vitamin D analogues up-regulate p21 and p27 during growth inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Br. J. Cancer 1997, 76, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, M.R.; Hsieh, C.C.; Reisner, P.D.; Rabek, J.P.; Scott, S.G.; Kuninger, D.T.; Papaconstantinou, J. Evidence for posttranscriptional regulation of C/EBPα and C/EBPβ isoform expression during the lipopolysaccharide-mediated acute-phase response. Mol. Cell Biol. 1996, 16, 2295–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot, D.; Skepper, J.N.; Hegyi, L.; Farzaneh-Far, A.; Shanahan, C.M.; Weissberg, P.L. The role of apoptosis in the initiation of vascular calcification. Z. Kardiol. 2001, 90, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakos, S.; Barletta, F.; Huening, M.; Dhawan, P.; Liu, Y.; Porta, A.; Peng, X. Vitamin D target proteins: Function and regulation. J. Cell Biochem. 2003, 88, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haussler, M.R.; Whitfield, G.K.; Kaneko, I.; Haussler, C.A.; Hsieh, D.; Hsieh, J.C.; Jurutka, P.W. Molecular mechanisms of vitamin D action. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2013, 92, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.C.; Kong, J.; Wei, M.; Chen, Z.F.; Liu, S.Q.; Cao, L.P. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a negative endocrine regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 110, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera, M.; Anguiano, L.; Clotet, S.; Roca-Ho, H.; Rebull, M.; Pascual, J.; Soler, M.J. Paricalcitol modulates ACE2 shedding and renal ADAM17 in NOD mice beyond proteinuria. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2016, 310, F534–F546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, C.; Hales, P.; Kaushik, V.; Dick, L.; Gavin, J.; Tang, J.; Godbout, K.; Parsons, T.; Baronas, E.; Hsieh, F.; et al. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 14838–14843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.A.; Simoes e Silva, A.C.; Maric, C.; Silva, D.M.; Machado, R.P.; de Buhr, I.; Heringer-Walther, S.; Pinheiro, S.V.; Lopes, M.T.; Bader, M.; et al. Angiotensin-(1-7) is an endogenous ligand for the G protein-coupled receptor Mas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8258–8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anguiano, L.; Riera, M.; Pascual, J.; Valdivielso, J.M.; Barrios, C.; Betriu, A.; Mojal, S.; Fernandez, E.; Soler, M.J.; NEFRONA Study. Circulating angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 activity in patients with chronic kidney disease without previous history of cardiovascular disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, 1176–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamming, I.; Cooper, M.E.; Haagmans, B.L.; Hooper, N.M.; Korstanje, R.; Osterhaus, A.D.; Timens, W.; Turner, A.J.; Navis, G.; van Goor, H. The emerging role of ACE2 in physiology and disease. J. Pathol. 2007, 212, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautrette, A.; Li, S.; Alili, R.; Sunnarborg, S.W.; Burtin, M.; Lee, D.C.; Friedlander, G.; Terzi, F. Angiotensin II and EGF receptor cross-talk in chronic kidney diseases: A new therapeutic approach. Nat. Med. 2005, 11, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Gao, L.; Yang, Y.; Tong, D.; Guo, B.; Liu, L.; Li, Z.; Song, T.; Huang, C. miR-145 mediates the antiproliferative and gene regulatory effects of vitamin D3 by directly targeting E2F3 in gastric cancer cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 7675–7685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, K.R.; Sheehy, N.T.; White, M.P.; Berry, E.C.; Morton, S.U.; Muth, A.N.; Lee, T.H.; Miano, J.M.; Ivey, K.N.; Srivastava, D. miR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature 2009, 460, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, J.; Lin, Y.; Xu, D.Z.; Lu, Q.; Deitch, E.A.; Huo, Y.; Delphin, E.S.; Zhang, C. MicroRNA-145, a novel smooth muscle cell phenotypic marker and modulator, controls vascular neointimal lesion formation. Circ. Res. 2009, 105, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doberstein, K.; Steinmeyer, N.; Hartmetz, A.K.; Eberhardt, W.; Mittelbronn, M.; Harter, P.N.; Juengel, E.; Blaheta, R.; Pfeilschifter, J.; Gutwein, P. MicroRNA-145 targets the metalloprotease ADAM17 and is suppressed in renal cell carcinoma patients. Neoplasia 2013, 15, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Lopez, N.; Panizo, S.; Arcidiacono, M.V.; de la Fuente, S.; Martinez-Arias, L.; Ottaviano, E.; Ulloa, C.; Ruiz-Torres, M.P.; Rodriguez, I.; Cannata-Andia, J.B.; et al. Vitamin D Treatment Prevents Uremia-Induced Reductions in Aortic microRNA-145 Attenuating Osteogenic Differentiation despite Hyperphosphatemia. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, R.; Carmeliet, G.; Verlinden, L.; van Etten, E.; Verstuyf, A.; Luderer, H.F.; Lieben, L.; Mathieu, C.; Demay, M. Vitamin D and human health: Lessons from vitamin D receptor null mice. Endocr. Rev. 2008, 29, 726–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, P.J.; Gysemans, C.; Verstuyf, A.; Mathieu, A.C. Vitamin D’s Effect on Immune Function. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, L.; Noyola-Martinez, N.; Barrera, D.; Hernandez, G.; Avila, E.; Halhali, A.; Larrea, F. Calcitriol inhibits TNF-α-induced inflammatory cytokines in human trophoblasts. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2009, 81, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charbonneau, M.; Harper, K.; Grondin, F.; Pelmus, M.; McDonald, P.P.; Dubois, C.M. Hypoxia-inducible factor mediates hypoxic and tumor necrosis factor α-induced increases in tumor necrosis factor-α converting enzyme/ADAM17 expression by synovial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 33714–33724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andress, D.L. Vitamin D in chronic kidney disease: A systemic role for selective vitamin D receptor activation. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Acharya, M.; Tian, J.; Hippensteel, R.L.; Melnick, J.Z.; Qiu, P.; Williams, L.; Batlle, D. Antiproteinuric effect of oral paricalcitol in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2005, 68, 2823–2828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alborzi, P.; Patel, N.A.; Peterson, C.; Bills, J.E.; Bekele, D.M.; Bunaye, Z.; Light, R.P.; Agarwal, R. Paricalcitol reduces albuminuria and inflammation in chronic kidney disease: A randomized double-blind pilot trial. Hypertension 2008, 52, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimaleswaran, K.S.; Cavadino, A.; Berry, D.J.; LifeLines Cohort Study Investigators; Jorde, R.; Dieffenbach, A.K.; Lu, C.; Alves, A.C.; Heerspink, H.J.; Tikkanen, E.; et al. Association of vitamin D status with arterial blood pressure and hypertension risk: A mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014, 2, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, J.P.; Zhou, A.; Hypponen, E. Vitamin D Deficiency Increases Mortality Risk in the UK Biobank: A Nonlinear Mendelian Randomization Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 1552–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thadhani, R.; Tamez, H.; Solomon, S.D. Vitamin D Therapy and Cardiac Function in Chronic Kidney Disease-Reply. JAMA 2012, 307, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Investigators, J.D.; Shoji, T.; Inaba, M.; Fukagawa, M.; Ando, R.; Emoto, M.; Fujii, H.; Fujimori, A.; Fukui, M.; Hase, H.; et al. Effect of Oral Alfacalcidol on Clinical Outcomes in Patients Without Secondary Hyperparathyroidism Receiving Maintenance Hemodialysis: The J-DAVID Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 320, 2325–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervloet, M.G.; Hsu, S.; de Boer, I.H. Vitamin D supplementation in people with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2023, 104, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, R.P. Vitamin D: Criteria for safety and efficacy. Nutr. Rev. 2008, 66, S178–S181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaClair, R.E.; Hellman, R.N.; Karp, S.L.; Kraus, M.; Ofner, S.; Li, Q.; Graves, K.L.; Moe, S.M. Prevalence of calcidiol deficiency in CKD: A cross-sectional study across latitudes in the United States. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2005, 45, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melamed, M.L.; Astor, B.; Michos, E.D.; Hostetter, T.H.; Powe, N.R.; Muntner, P. 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, race, and the progression of kidney disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 2631–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, C.; Hamano, T.; Fujii, N.; Matsui, I.; Tomida, K.; Mikami, S.; Inoue, K.; Obi, Y.; Okada, N.; Tsubakihara, Y.; et al. Combined use of vitamin D status and FGF23 for risk stratification of renal outcome. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, A.I.; Sallman, A.; Santiz, Z.; Hollis, B.W. Defective photoproduction of cholecalciferol in normal and uremic humans. J. Nutr. 1984, 114, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemoto, F.; Shinki, T.; Yokoyama, K.; Inokami, T.; Hara, S.; Yamada, A.; Kurokawa, K.; Uchida, S. Gene expression of vitamin D hydroxylase and megalin in the remnant kidney of nephrectomized rats. Kidney Int. 2003, 64, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nykjaer, A.; Dragun, D.; Walther, D.; Vorum, H.; Jacobsen, C.; Herz, J.; Melsen, F.; Christensen, E.I.; Willnow, T.E. An endocytic pathway essential for renal uptake and activation of the steroid 25-(OH) vitamin D3. Cell 1999, 96, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallieni, M.; Kamimura, S.; Ahmed, A.; Bravo, E.; Delmez, J.; Slatopolsky, E.; Dusso, A. Kinetics of monocyte 1 alpha-hydroxylase in renal failure. Am. J. Physiol. 1995, 268, F746–F753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusso, A.; Lopez-Hilker, S.; Rapp, N.; Slatopolsky, E. Extra-renal production of calcitriol in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 1988, 34, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zierold, C.; Reinholz, G.G.; Mings, J.A.; Prahl, J.M.; DeLuca, H.F. Regulation of the procine 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-24-hydroxylase (CYP24) by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and parathyroid hormone in AOK-B50 cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000, 381, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketteler, M.; Block, G.A.; Evenepoel, P.; Fukagawa, M.; Herzog, C.A.; McCann, L.; Moe, S.M.; Shroff, R.; Tonelli, M.A.; Toussaint, N.D.; et al. Executive summary of the 2017 KDIGO Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD) Guideline Update: What’s changed and why it matters. Kidney Int. 2017, 92, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demay, M.B.; Pittas, A.G.; Bikle, D.D.; Diab, D.L.; Kiely, M.E.; Lazaretti-Castro, M.; Lips, P.; Mitchell, D.M.; Murad, M.H.; Powers, S.; et al. Vitamin D for the Prevention of Disease: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, 1907–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melamed, M.L.; Chonchol, M.; Gutierrez, O.M.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kendrick, J.; Norris, K.; Scialla, J.J.; Thadhani, R. The Role of Vitamin D in CKD Stages 3 to 4: Report of a Scientific Workshop Sponsored by the National Kidney Foundation. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2018, 72, 834–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, H.S.; Vervloet, M.; Cavalier, E.; Bacchetta, J.; de Borst, M.H.; Bover, J.; Cozzolino, M.; Ferreira, A.C.; Hansen, D.; Herrmann, M.; et al. The role of nutritional vitamin D in chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder in children and adults with chronic kidney disease, on dialysis, and after kidney transplantation-a European consensus statement. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2025, 40, 797–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergada, L.; Pallares, J.; Maria Vittoria, A.; Cardus, A.; Santacana, M.; Valls, J.; Cao, G.; Fernandez, E.; Dolcet, X.; Dusso, A.S.; et al. Role of local bioactivation of vitamin D by CYP27A1 and CYP2R1 in the control of cell growth in normal endometrium and endometrial carcinoma. Lab. Investig. 2014, 94, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.J.; Ritter, C.S.; Knutson, J.C.; Strugnell, S.A. The vitamin D prodrugs 1α(OH)D2, 1α(OH)D3 and BCI-210 suppress PTH secretion by bovine parathyroid cells. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2006, 21, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shroff, R.; Wan, M.; Gullett, A.; Ledermann, S.; Shute, R.; Knott, C.; Wells, D.; Aitkenhead, H.; Manickavasagar, B.; van’t Hoff, W.; et al. Ergocalciferol supplementation in children with CKD delays the onset of secondary hyperparathyroidism: A randomized trial. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandula, P.; Dobre, M.; Schold, J.D.; Schreiber, M.J., Jr.; Mehrotra, R.; Navaneethan, S.D. Vitamin D supplementation in chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Orav, E.J.; Staehelin, H.B.; Meyer, O.W.; Theiler, R.; Dick, W.; Willett, W.C.; Egli, A. Monthly High-Dose Vitamin D Treatment for the Prevention of Functional Decline: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaney, R.P.; Armas, L.A.; Shary, J.R.; Bell, N.H.; Binkley, N.; Hollis, B.W. 25-Hydroxylation of vitamin D3: Relation to circulating vitamin D3 under various input conditions. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1738–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F.; Biancuzzo, R.M.; Chen, T.C.; Klein, E.K.; Young, A.; Bibuld, D.; Reitz, R.; Salameh, W.; Ameri, A.; Tannenbaum, A.D. Vitamin D2 is as effective as vitamin D3 in maintaining circulating concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armas, L.A.; Hollis, B.W.; Heaney, R.P. Vitamin D2 is much less effective than vitamin D3 in humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 89, 5387–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, T.O.; Zhang, J.H.; Parra, E.; Ellis, B.K.; Simpson, C.; Lee, W.M.; Balko, J.; Fu, L.; Wong, B.Y.; Cole, D.E. Vitamin D binding protein is a key determinant of 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in infants and toddlers. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.R.; Molnar, F.; Perakyla, M.; Qiao, S.; Kalueff, A.V.; St-Arnaud, R.; Carlberg, C.; Tuohimaa, P. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 is an agonistic vitamin D receptor ligand. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010, 118, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprague, S.M.; Crawford, P.W.; Melnick, J.Z.; Strugnell, S.A.; Ali, S.; Mangoo-Karim, R.; Lee, S.; Petkovich, P.M.; Bishop, C.W. Use of Extended-Release Calcifediol to Treat Secondary Hyperparathyroidism in Stages 3 and 4 Chronic Kidney Disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 2016, 44, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strugnell, S.A.; Sprague, S.M.; Ashfaq, A.; Petkovich, M.; Bishop, C.W. Rationale for Raising Current Clinical Practice Guideline Target for Serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D in Chronic Kidney Disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 2019, 49, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.W.; Ashfaq, A.; Choe, J.; Strugnell, S.A.; Johnson, L.L.; Norris, K.C.; Sprague, S.M. Extended-Release Calcifediol Normalized 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D and Prevented Progression of Secondary Hyperparathyroidism in Hemodialysis Patients in a Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Nephrol. 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Q.; Hou, Y.C.; Zheng, C.M.; Lu, C.L.; Liu, W.C.; Wu, C.C.; Huang, M.T.; Lin, Y.F.; Lu, K.C. Cholecalciferol Additively Reduces Serum Parathyroid Hormone and Increases Vitamin D and Cathelicidin Levels in Paricalcitol-Treated Secondary Hyperparathyroid Hemodialysis Patients. Nutrients 2016, 8, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J. Vitamin D Enhancement of Adipose Biology: Implications on Obesity-Associated Cardiometabolic Diseases. Nutrients 2025, 17, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoenderop, J.G.; Chon, H.; Gkika, D.; Bluyssen, H.A.; Holstege, F.C.; St-Arnaud, R.; Braam, B.; Bindels, R.J. Regulation of gene expression by dietary Ca2+ in kidneys of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1 α-hydroxylase knockout mice. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haussler, M.R.; Whitfield, G.K.; Kaneko, I.; Forster, R.; Saini, R.; Hsieh, J.C.; Haussler, C.A.; Jurutka, P.W. The role of vitamin D in the FGF23, klotho, and phosphate bone-kidney endocrine axis. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2012, 13, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urakawa, I.; Yamazaki, Y.; Shimada, T.; Iijima, K.; Hasegawa, H.; Okawa, K.; Fujita, T.; Fukumoto, S.; Yamashita, T. Klotho converts canonical FGF receptor into a specific receptor for FGF23. Nature 2006, 444, 770–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.C.; Shi, M.; Zhang, J.; Quinones, H.; Kuro-o, M.; Moe, O.W. Klotho deficiency is an early biomarker of renal ischemia-reperfusion injury and its replacement is protective. Kidney Int. 2010, 78, 1240–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindberg, K.; Amin, R.; Moe, O.W.; Hu, M.C.; Erben, R.G.; Ostman Wernerson, A.; Lanske, B.; Olauson, H.; Larsson, T.E. The kidney is the principal organ mediating klotho effects. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 2169–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babitt, J.L.; Sitara, D. Crosstalk between fibroblast growth factor 23, iron, erythropoietin, and inflammation in kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2019, 28, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.; White, K.E. Coupling fibroblast growth factor 23 production and cleavage: Iron deficiency, rickets, and kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2014, 23, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolek, O.I.; Hines, E.R.; Jones, M.D.; LeSueur, L.K.; Lipko, M.A.; Kiela, P.R.; Collins, J.F.; Haussler, M.R.; Ghishan, F.K. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 upregulates FGF23 gene expression in bone: The final link in a renal-gastrointestinal-skeletal axis that controls phosphate transport. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2005, 289, G1036–G1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, C.; Amaral, A.P.; Oskouei, B.; Hu, M.C.; Sloan, A.; Isakova, T.; Gutierrez, O.M.; Aguillon-Prada, R.; Lincoln, J.; Hare, J.M.; et al. FGF23 induces left ventricular hypertrophy. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 4393–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.E.; Beck, L.; Hill Gallant, K.M.; Chen, Y.; Moe, O.W.; Kuro, O.M.; Moe, S.M.; Aikawa, E. Phosphate in Cardiovascular Disease: From New Insights Into Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Implications. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 584–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.W.; Wang, Y.K.; Li, S.J.; Yin, G.T.; Li, D. Elevated Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 Impairs Endothelial Function through the NF-κB Signaling Pathway. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2023, 30, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wungu, C.D.K.; Susilo, H.; Alsagaff, M.Y.; Witarto, B.S.; Witarto, A.P.; Pakpahan, C.; Gusnanto, A. Role of klotho and fibroblast growth factor 23 in arterial calcification, thickness, and stiffness: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Lopez, N.; Panizo, S.; Alonso-Montes, C.; Roman-Garcia, P.; Rodriguez, I.; Martinez-Salgado, C.; Dusso, A.S.; Naves, M.; Cannata-Andia, J.B. Direct inhibition of osteoblastic Wnt pathway by fibroblast growth factor 23 contributes to bone loss in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2016, 90, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetta, J.; Sea, J.L.; Chun, R.F.; Lisse, T.S.; Wesseling-Perry, K.; Gales, B.; Adams, J.S.; Salusky, I.B.; Hewison, M. Fibroblast growth factor 23 inhibits extrarenal synthesis of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in human monocytes. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajisnik, T.; Bjorklund, P.; Marsell, R.; Ljunggren, O.; Akerstrom, G.; Jonsson, K.B.; Westin, G.; Larsson, T.E. Fibroblast growth factor-23 regulates parathyroid hormone and 1α-hydroxylase expression in cultured bovine parathyroid cells. J. Endocrinol. 2007, 195, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, T.; Hasegawa, H.; Yamazaki, Y.; Muto, T.; Hino, R.; Takeuchi, Y.; Fujita, T.; Nakahara, K.; Fukumoto, S.; Yamashita, T. FGF-23 is a potent regulator of vitamin D metabolism and phosphate homeostasis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004, 19, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.H.; Wu, C.H.; Chou, N.K.; Tseng, L.J.; Huang, I.P.; Wang, C.H.; Wu, V.C.; Chu, T.S. High plasma C-terminal FGF-23 levels predict poor outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease superimposed with acute kidney injury. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2020, 11, 2040622320964161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuro-o, M.; Matsumura, Y.; Aizawa, H.; Kawaguchi, H.; Suga, T.; Utsugi, T.; Ohyama, Y.; Kurabayashi, M.; Kaname, T.; Kume, E.; et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature 1997, 390, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyra, J.A.; Hu, M.C.; Moe, O.W. Klotho in Clinical Nephrology: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tan, H.; Xu, J.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Chen, Q.; Hong, X.; Fu, H.; Hou, F.F.; et al. Klotho-derived peptide 6 ameliorates diabetic kidney disease by targeting Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Kidney Int. 2022, 102, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Flores, B.; Gillings, N.; Bian, A.; Cho, H.J.; Yan, S.; Liu, Y.; Levine, B.; Moe, O.W.; Hu, M.C. αKlotho Mitigates Progression of AKI to CKD through Activation of Autophagy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 2331–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanucil, C.; Kentrup, D.; Campos, I.; Czaya, B.; Heitman, K.; Westbrook, D.; Osis, G.; Grabner, A.; Wende, A.R.; Vallejo, J.; et al. Soluble α-klotho and heparin modulate the pathologic cardiac actions of fibroblast growth factor 23 in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2022, 102, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorr, K.; Kammer, M.; Reindl-Schwaighofer, R.; Lorenz, M.; Prikoszovich, T.; Marculescu, R.; Beitzke, D.; Wielandner, A.; Erben, R.G.; Oberbauer, R. Randomized Trial of Etelcalcetide for Cardiac Hypertrophy in Hemodialysis. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1616–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbueken, D.; Moe, O.W. Strategies to lower fibroblast growth factor 23 bioactivity. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2022, 37, 1800–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalhoub, V.; Shatzen, E.M.; Ward, S.C.; Davis, J.; Stevens, J.; Bi, V.; Renshaw, L.; Hawkins, N.; Wang, W.; Chen, C.; et al. FGF23 neutralization improves chronic kidney disease-associated hyperparathyroidism yet increases mortality. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 2543–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, R.E.; Jurutka, P.W.; Hsieh, J.C.; Haussler, C.A.; Lowmiller, C.L.; Kaneko, I.; Haussler, M.R.; Kerr Whitfield, G. Vitamin D receptor controls expression of the anti-aging klotho gene in mouse and human renal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 414, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifheit-Nestler, M.; Grabner, A.; Hermann, L.; Richter, B.; Schmitz, K.; Fischer, D.C.; Yanucil, C.; Faul, C.; Haffner, D. Vitamin D treatment attenuates cardiac FGF23/FGFR4 signaling and hypertrophy in uremic rats. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 1493–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanbay, M.; Demiray, A.; Afsar, B.; Covic, A.; Tapoi, L.; Ureche, C.; Ortiz, A. Role of Klotho in the Development of Essential Hypertension. Hypertension 2021, 77, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Qian, J.R.; Li, S.S.; Liu, Q.F. Inflammation-Induced Klotho Deficiency: A Possible Key Driver of Chronic Kidney Disease Progression. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2025, 18, 2507–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drew, D.A.; Katz, R.; Kritchevsky, S.; Ix, J.H.; Shlipak, M.G.; Newman, A.B.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Fried, L.F.; Sarnak, M.; Gutierrez, O.M.; et al. Soluble Klotho and Incident Hypertension. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 16, 1502–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Chang, Z.Y.; Tsai, F.J.; Chen, S.Y. Resveratrol Pretreatment Ameliorates Concanavalin A-Induced Advanced Renal Glomerulosclerosis in Aged Mice through Upregulation of Sirtuin 1-Mediated Klotho Expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, Y.O.; Ibrahim, S.M.; Zaki, H.F.; Elshazly, S.M.; Badawi, G.A. Targeting α-Klotho Protein by Agmatine and Pioglitazone Is a New Avenue against Diabetic Nephropathy. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2025, 8, 2493–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nincevic, V.; Omanovic Kolaric, T.; Roguljic, H.; Kizivat, T.; Smolic, M.; Bilic Curcic, I. Renal Benefits of SGLT 2 Inhibitors and GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: Evidence Supporting a Paradigm Shift in the Medical Management of Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Katz, R.; Bullen, A.L.; Chaves, P.H.M.; de Leeuw, P.W.; Kroon, A.A.; Houben, A.; Shlipak, M.G.; Ix, J.H. Intact and C-Terminal FGF23 Assays-Do Kidney Function, Inflammation, and Low Iron Influence Relationships with Outcomes? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, e4875–e4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, B.B.; Bergwitz, C. FGF23 signalling and physiology. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2021, 66, R23–R32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.C.; Reneau, J.A.; Shi, M.; Takahashi, M.; Chen, G.; Mohammadi, M.; Moe, O.W. C-terminal fragment of fibroblast growth factor 23 improves heart function in murine models of high intact fibroblast growth factor 23. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2024, 326, F584–F599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzaman, N.S.; Dawson-Hughes, B.; Nelson, J.; D’Alessio, D.; Pittas, A.G. Vitamin D status of black and white Americans and changes in vitamin D metabolites after varied doses of vitamin D supplementation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.A.; Vande Vord, P.J.; Wooley, P.H. Polymorphism in the vitamin D receptor gene and bone mass in African-American and white mothers and children: A preliminary report. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2000, 59, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powe, C.E.; Evans, M.K.; Wenger, J.; Zonderman, A.B.; Berg, A.H.; Nalls, M.; Tamez, H.; Zhang, D.; Bhan, I.; Karumanchi, S.A.; et al. Vitamin D-binding protein and vitamin D status of black Americans and white Americans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1991–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, S.; Theiler-Schwetz, V.; Pludowski, P.; Zelzer, S.; Meinitzer, A.; Karras, S.N.; Misiorowski, W.; Zittermann, A.; Marz, W.; Trummer, C. Hypercalcemia in Pregnancy Due to CYP24A1 Mutations: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derose, S.F.; Rutkowski, M.P.; Levin, N.W.; Liu, I.L.; Shi, J.M.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Crooks, P.W. Incidence of end-stage renal disease and death among insured African Americans with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2009, 76, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Feature | Standard Immunoassays (e.g., ELISA, Chemiluminescence) | LC-MS/MS (Gold Standard) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Relies on antibodies binding to 25(OH)D. | Relies on separating and identifying molecules by mass and charge. |

| Specificity | Low to Moderate. Antibodies often cross-react with other vitamin D metabolites (24,25(OH)2D and 25(OH)D2), leading to overestimation of true 25(OH)D levels. | High. Precisely measures individual metabolites separately, providing true concentrations of 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2. |

| Matrix Effects | High. Susceptible to interference from lipids or other serum components. | Low. Pre-separation via LC minimizes matrix interference. |

| Cost/Throughput | Lower cost, high throughput (suitable for large labs) | Higher initial cost, requires specialized equipment and expertise. |

| Clinical Standard | Use frequently, but results may lack accuracy for diagnosis | Preferred Standard for accurate diagnosis and clinical trials. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dusso, A.S.; Porta, D.J.; Bernal-Mizrachi, C. Current Controversies on Adequate Circulating Vitamin D Levels in CKD. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010108

Dusso AS, Porta DJ, Bernal-Mizrachi C. Current Controversies on Adequate Circulating Vitamin D Levels in CKD. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010108

Chicago/Turabian StyleDusso, Adriana S., Daniela J. Porta, and Carlos Bernal-Mizrachi. 2026. "Current Controversies on Adequate Circulating Vitamin D Levels in CKD" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010108

APA StyleDusso, A. S., Porta, D. J., & Bernal-Mizrachi, C. (2026). Current Controversies on Adequate Circulating Vitamin D Levels in CKD. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010108