Improvement of Diagnostics in NSCLC Patients with MET Exon 14 Mutations Using Complementary DNA/RNA-NGS and Identification of Two Novel Exonic Splicing Mutations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification of METex14 Positive NSCLC Patients

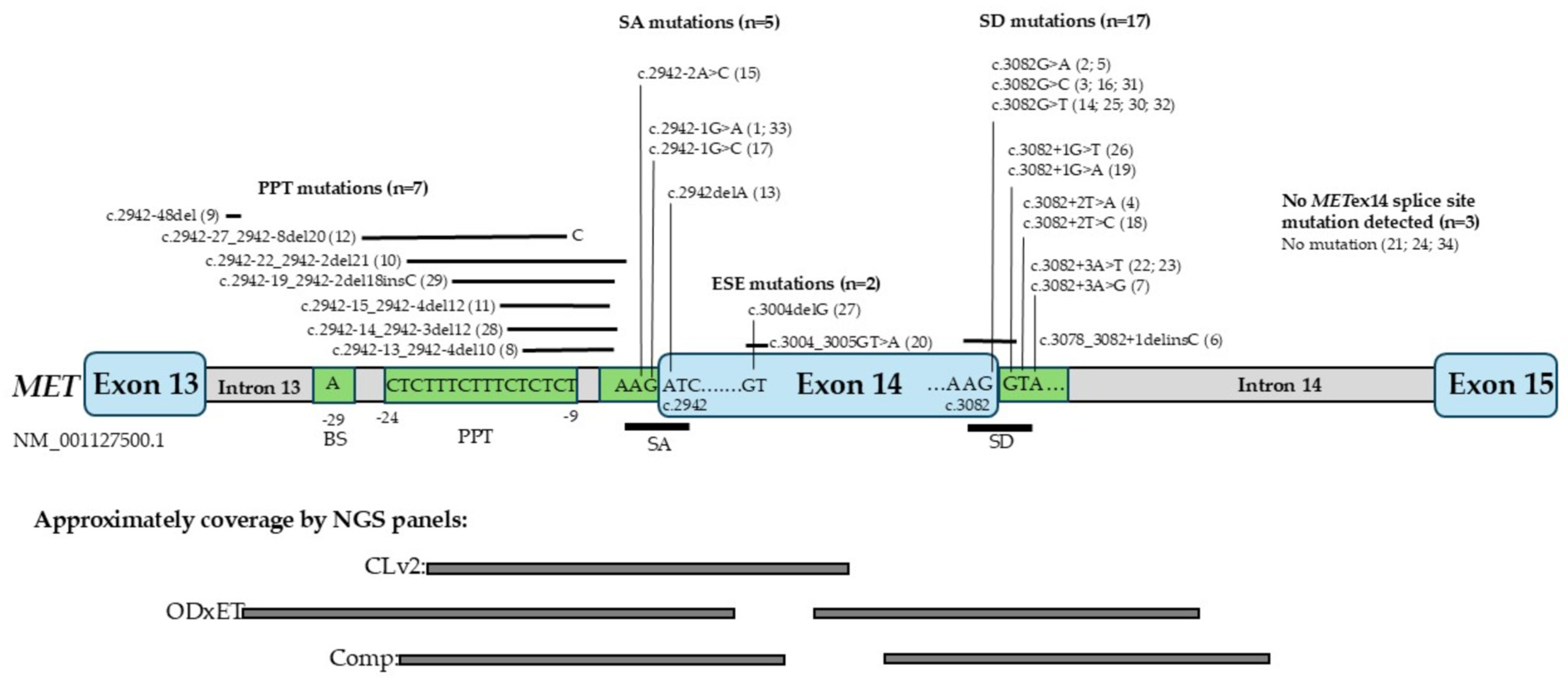

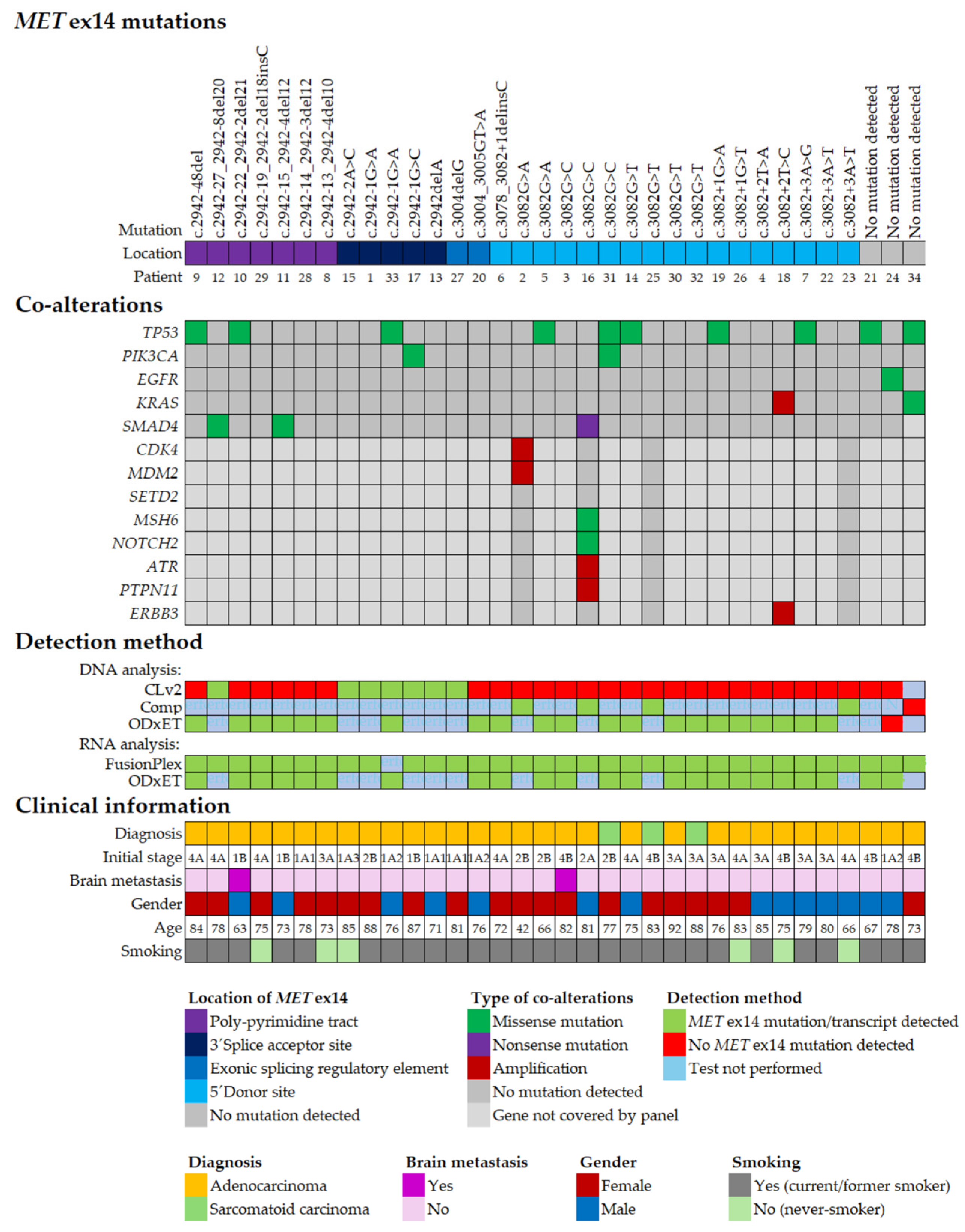

2.2. Subtypes of METex14 Mutations

2.3. Co-Occurring Genomic Alterations in METex14 Positive NSCLC

2.4. Clinical Characteristics of METex14 Positive NSCLC

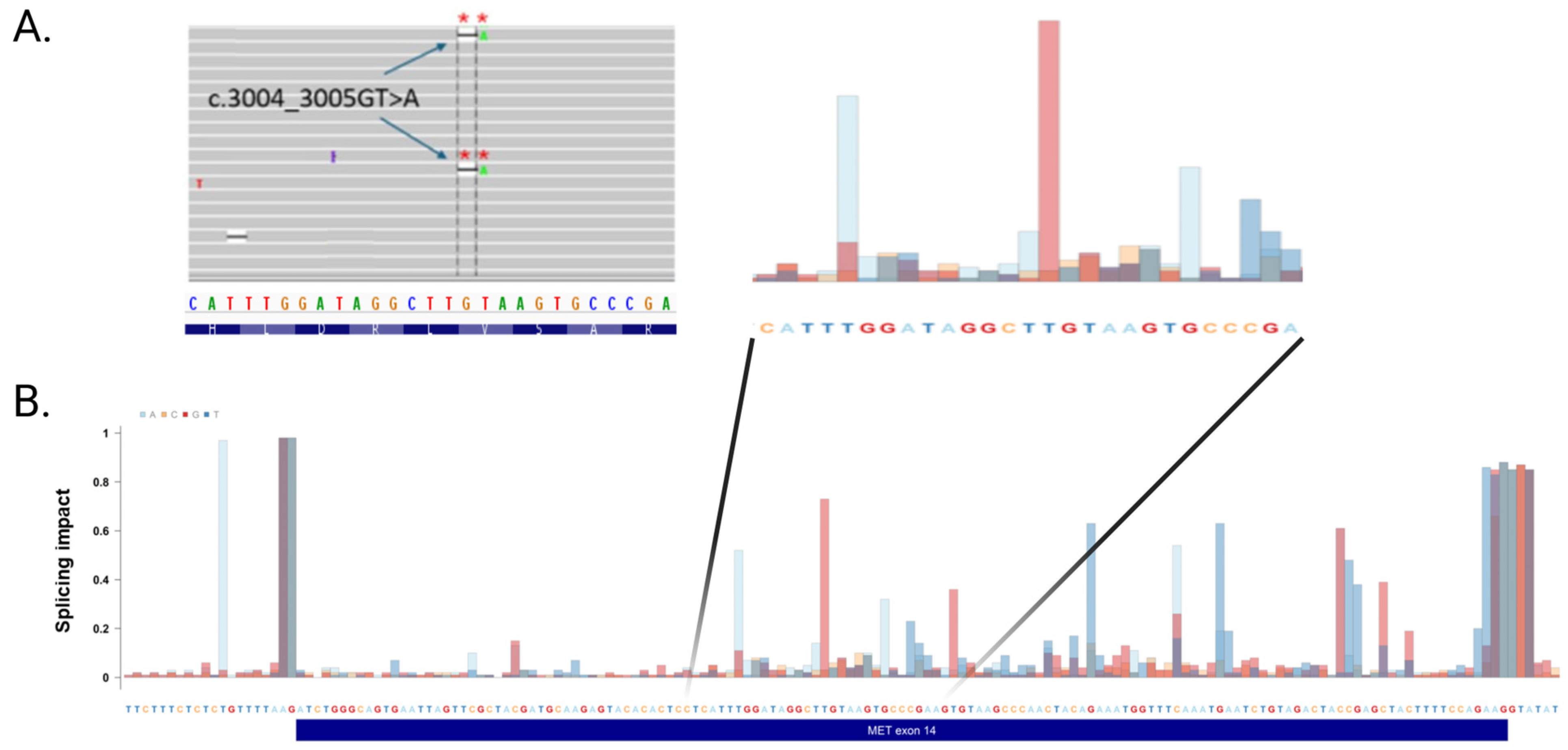

2.5. Mutations in an Exonic Splicing Enhancer in METex14 Dependent for Splicing

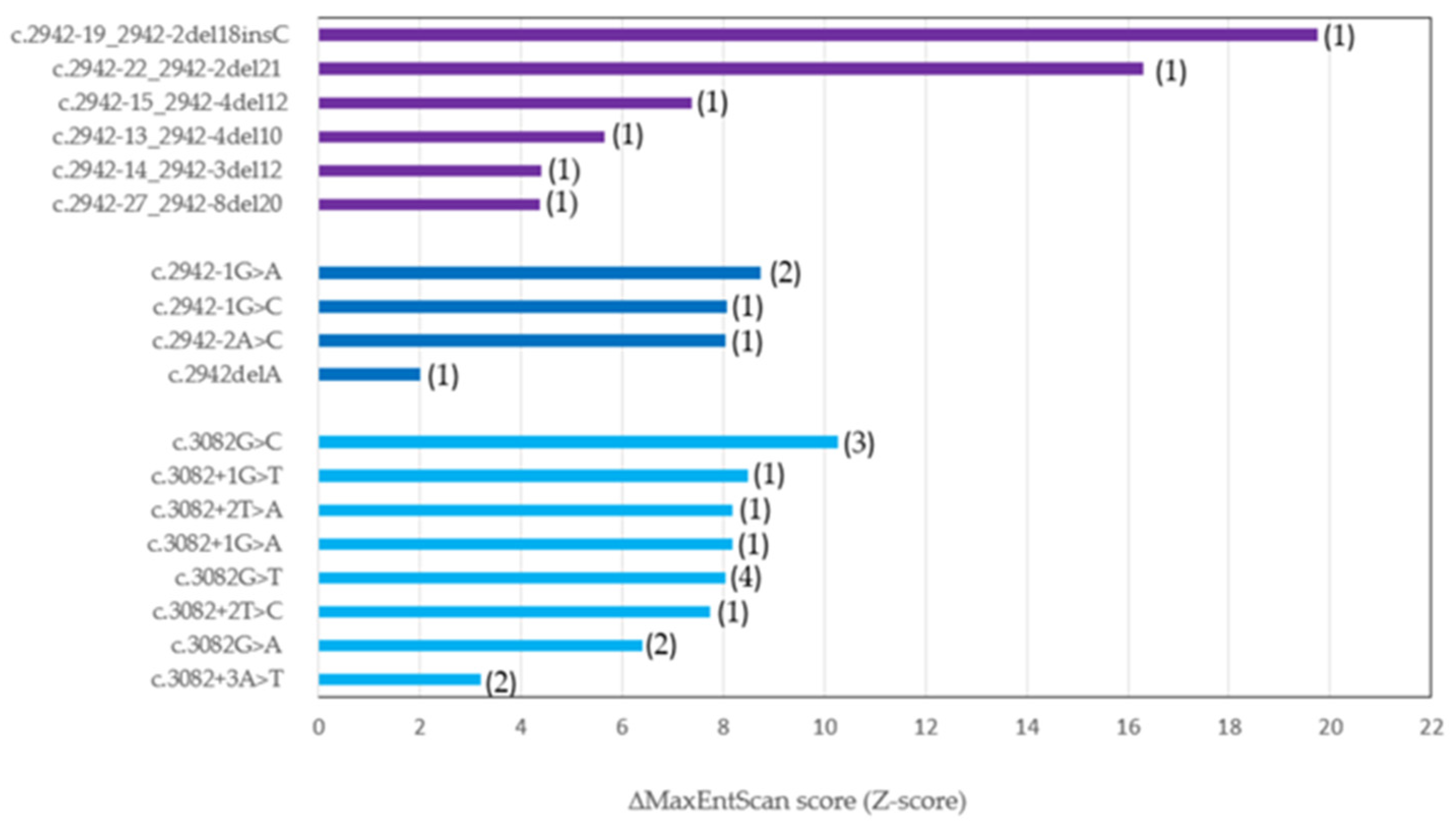

2.6. In Silico Prediction of METex14 Splice Site Mutations

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patient Cohort and Molecular Diagnostic Testing

4.2. Genomic Profiling by Next-Generation Sequencing

4.3. Bioinformatic Analysis

5. Conclusions

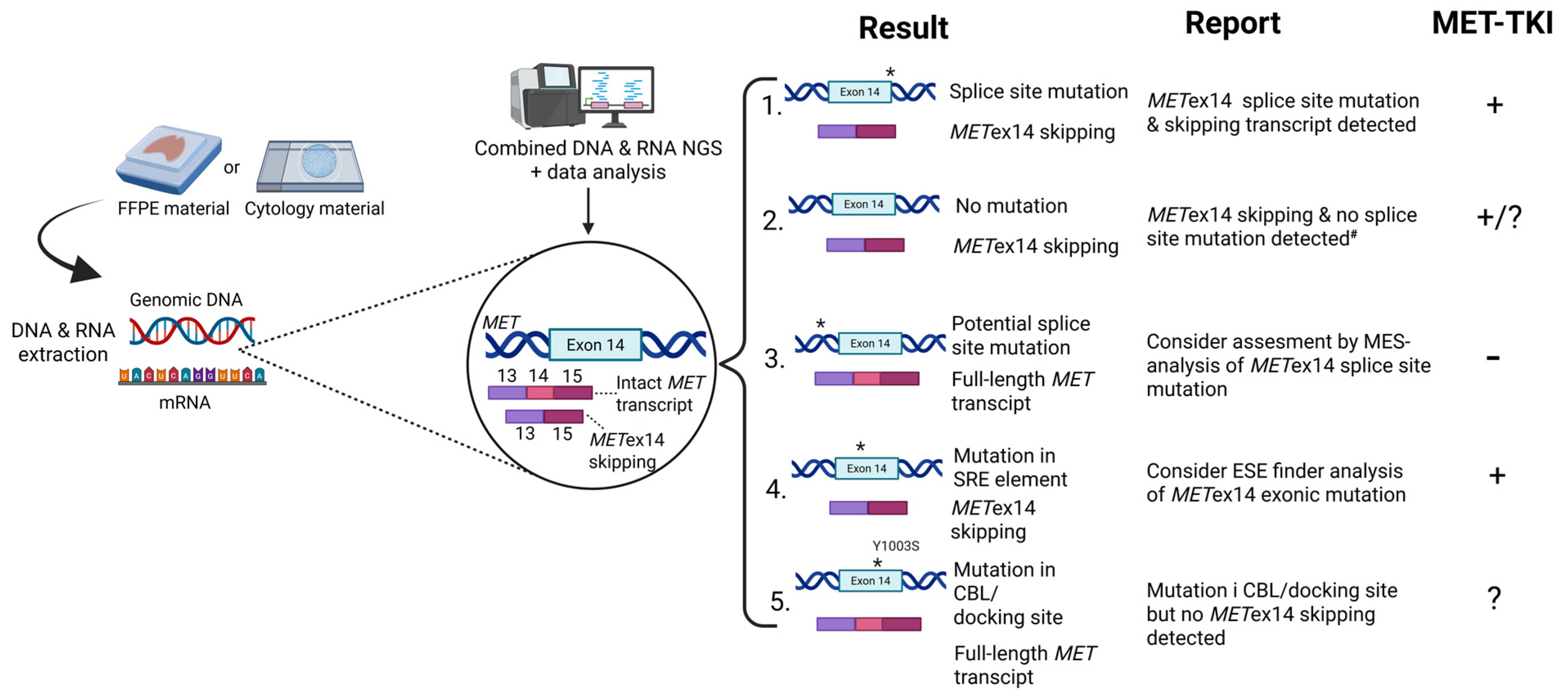

- When using DNA-NGS technology to detect METex14 skipping variants, it is important to note that different panels, such as CLv2, ODxET, and Comp, are designed to capture splice sites mutations in specific regions of exon 14.

- Complementary DNA- and RNG-NGS are needed for optimal detection of METex14 skipping in real-world NSCLC patients.

- The presence of the aberrant MET transcript is the most predictive biomarker for using MET-TKIs.

- Bioinformatics tools such as MES and SpTransformer provide additional information regarding impact of each METex14 mutation on aberrant splicing and the altered binding site, respectively.

- Two novel exonic mutations are also capable of causing abnormal splicing of METex14, in addition to variants localized in canonical splice sites.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cooper, C.S.; Park, M.; Blair, D.G.; Tainsky, M.A.; Huebner, K.; Croce, C.M.; Vande Woude, G.F. Molecular cloning of a new transforming gene from a chemically transformed human cell line. Nature 1984, 311, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, G.M.; Ali, S.M.; Rosenzweig, M.; Chmielecki, J.; Lu, X.; Bauer, T.M.; Akimov, M.; Bufill, J.A.; Lee, C.; Jentz, D.; et al. Activation of MET via diverse exon 14 splicing alterations occurs in multiple tumor types and confers clinical sensitivity to MET inhibitors. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 850–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serna-Blasco, R.; Mediavilla-Medel, P.; Medina, K.; Sala, M.Á.; Aguiar, D.; Díaz-Serrano, A.; Antoñanzas, M.; Ocaña, J.; Mielgo, X.; Fernández, I.; et al. Comprehensive molecular profiling of advanced NSCLC using NGS: Prevalence of druggable mutations and clinical trial opportunities in the ATLAS study. Lung Cancer 2025, 204, 108550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Non-Small Lung Cancer (Version 1.2026). Guidelines Detail (nccn.org). Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Hendriks, L.E.; Kerr, K.M.; Menis, J.; Mok, T.S.; Nestle, U.; Passaro, A.; Peters, S.; Planchard, D.; Smit, E.F.; Solomon, B.J.; et al. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Oncogene-addicted metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, J.; Tawfik, O. Detection of MET exon 14 skipping mutations in non-small cell lung cancer: Overview and community perspective. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2021, 21, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peschard, P.; Fournier, T.M.; Lamorte, L.; Naujokas, M.A.; Band, H.; Langdon, W.Y.; Park, M. Mutation of the c-Cbl TKB-domain binding site on the Met receptor tyrosine kinase converts it into a transforming protein. Mol. Cell 2001, 8, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recondo, G.; Che, J.; Jänne, P.A.; Awad, M.M. Targeting MET Dysregulation in Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotto, S.; Gkountakos, A.; Carbognin, L.; Scarpa, A.; Tortora, G.; Bria, E. MET exon 14 juxtamembrane splicing mutations: Clinical and therapeutical perspectives for cancer therapy. Ann. Transl. Med. 2017, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.; Paget, S.; Kherrouche, Z.; Truong, M.J.; Vinchent, A.; Meneboo, J.P.; Sebda, S.; Werkmeister, E.; Descarpentries, C.; Figeac, M.; et al. Transforming properties of MET receptor exon 14 skipping can be recapitulated by loss of the CBL ubiquitin ligase binding site. FEBS Lett. 2023, 597, 2301–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqua, M.; Botti, O.; Arigoni, M.; Gioelli, N.; Serini, G.; Calogero, R.; Boccaccio, C.; Comoglio, P.M.; Altintas, D.M. MET∆14 promotes a ligand-dependent, AKT-driven invasive growth. Life Sci. Alliance 2022, 5, e202201409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Hu, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Yu, M.; Wang, H.; Zhao, B. MET exon 14 skipping mutation drives cancer progression and recurrence via activation of SMAD2 signalling. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 130, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, M.J.; Pawlak, G.; Meneboo, J.P.; Sebda, S.; Fernandes, M.; Figeac, M.; Elati, M.; Tulasne, D. Comprehensive map of the regulatory network triggered by MET exon 14 skipping reveals important involvement of the RAS-ERK signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, R.K.; Anczuków, O. RNA splicing dysregulation and the hallmarks of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2023, 23, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tang, J.; Xiang, J. Alternative Splicing in Tumorigenesis and Cancer Therapy. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, R.F.; Abdel-Wahab, O. Dysregulation and therapeutic targeting of RNA splicing in cancer. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, B.S.; Krainer, A.R. When the genetic code is not enough—How sequence variations can affect pre-mRNA splicing and cause (complex) disease. In Genetics of Complex Human Diseases; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2009; Chapter 15; pp. 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Roca, X.; Sachidanandam, R.; Krainer, A.R. Determinants of the inherent strength of human 5′ splice sites. RNA 2005, 11, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baten, A.K.; Chang, B.C.; Halgamuge, S.K.; Li, J. Splice site identification using probabilistic parameters and SVM classification. BMC Bioinform. 2006, 7, S15, Erratum in BMC Bioinform. 2007, 8, 241. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-7-S5-S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Sun, X.; Gao, Y.; Song, X.; Hu, X.; Gong, L.; Han, L.; He, M.; Wei, M. Targeting RNA splicing modulation: New perspectives for anticancer strategy? J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, L.L.; Doktor, T.K.; Flugt, K.K.; Petersen, U.S.S.; Petersen, R.; Andresen, B.S. All exons are not created equal-exon vulnerability determines the effect of exonic mutations on splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 4588–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Yin, J.; Bohlman, S.; Walker, P.; Dacic, S.; Kim, C.; Khan, H.; Liu, S.V.; Ma, P.C.; Nagasaka, M.; et al. Characterization of MET Exon 14 Skipping Alterations (in NSCLC) and Identification of Potential Therapeutic Targets Using Whole Transcriptome Sequencing. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2022, 3, 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, G.; Burge, C.B. Maximum entropy modeling of short sequence motifs with applications to RNA splicing signals. J. Comput. Biol. 2004, 11, 377–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.M.; Lee, J.K.; Madison, R.; Classon, A.; Kmak, J.; Frampton, G.M.; Alexander, B.M.; Venstrom, J.; Schrock, A.B. Characterization of 1,387 NSCLCs with MET exon 14 (METex14) skipping alterations (SA) and potential acquired resistance (AR) mechanisms. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 9511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Madison, R.; Classon, A.; Gjoerup, O.; Rosenzweig, M.; Frampton, G.M.; Alexander, B.M.; Oxnard, G.R.; Venstrom, J.M.; Awad, M.M.; et al. Characterization of Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancers with MET Exon 14 Skipping Alterations Detected in Tissue or Liquid: Clinicogenomics and Real-World Treatment Patterns. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5, 1354–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, N.; Liu, C.; Gu, Y.; Wang, R.; Jia, H.; Zhang, T.; Jiang, S.; Shi, J.; Chen, M.; Guan, M.X.; et al. SpliceTransformer predicts tissue-specific splicing linked to human diseases. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.L.; Vega-Warner, V.; Gillies, C.; Sampson, M.G.; Kher, V.; Sethi, S.K.; Otto, E.A. Whole Exome Sequencing Reveals Novel PHEX Splice Site Mutations in Patients with Hypophosphatemic Rickets. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, P.; Christopoulos, P.; D’Haene, N.; Gosney, J.; Normanno, N.; Schuuring, E.; Tsao, M.S.; Quinn, C.; Russell, J.; Keating, K.E.; et al. Proposal of real-world solutions for the implementation of predictive biomarker testing in patients with operable non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2025, 201, 108107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Yamada, K.M. Identification of a novel type of alternative splicing of a tyrosine kinase receptor. Juxtamembrane deletion of the c-met protein kinase C serine phosphorylation regulatory site. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 19457–19461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.C.; Jagadeeswaran, R.; Jagadeesh, S.; Tretiakova, M.S.; Nallasura, V.; Fox, E.A.; Hansen, M.; Schaefer, E.; Naoki, K.; Lader, A.; et al. Functional expression and mutations of c-Met and it’s therapeutic inhibition with SU11274 and small interfering RNA in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 1479–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COSMIC—Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Available online: https://www.cosmickb.org/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Chakravarty, D.; Gao, J.; Phillips, S.M.; Kundra, R.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Rudolph, J.E.; Yaeger, R.; Soumerai, T.; Nissan, M.H.; et al. OncoKB: A Precision Oncology Knowledge Base. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2017, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerami, E.; Gao, J.; Dogrusoz, U.; Gross, B.E.; Sumer, S.O.; Aksoy, B.A.; Jacobsen, A.; Byrne, C.J.; Heuer, M.; Larsson, E.; et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: An open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 401–404, Erratum in Cancer Discov. 2012, 2, 960. https://doi.org/10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Descarpentries, C.; Leprêtre, F.; Escande, F.; Kherrouche, Z.; Figeac, M.; Sebda, S.; Baldacci, S.; Grégoire, V.; Jamme, P.; Copin, M.C.; et al. Optimization of Routine Testing for MET Exon 14 Splice Site Mutations in NSCLC Patients. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018, 13, 1873–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, D.; Ben-Shachar, R.; Feliciano, J.; Gai, L.; Beauchamp, K.A.; Rivers, Z.; Hockenberry, A.J.; Harrison, G.; Guittar, J.; Catela, C.; et al. Actionable Structural Variant Detection via RNA-NGS-and DNA-NGS in Patients With Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2442970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayed, R.; Offin, M.; Mullaney, K.; Sukhadia, P.; Rios, K.; Desmeules, P.; Ptashkin, R.; Won, H.; Chang, J.; Halpenny, D.; et al. High Yield of RNA Sequencing for Targetable Kinase Fusions in Lung Adenocarcinomas with No Mitogenic Driver Alteration Detected by DNA Sequencing and Low Tumor Mutation Burden. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 4712–4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Ren, P.; Ma, J.; Guo, Y. Optimized Detection of Unknown MET Exon 14 Skipping Mutations in Routine Testing for Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2023, 7, e2200482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, S.; Sepúlveda, R.V.; Tapia, I.; Estay, C.; Soto, V.; Blanco, A.; González, E.; Armisen, R. MET Exon 14 Skipping and Novel Actionable Variants: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications in Latin American Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirot, B.; Doucet, L.; Benhenda, S.; Champ, J.; Meignin, V.; Lehmann-Che, J. MET Exon 14 Alterations and New Resistance Mutations to Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: Risk of Inadequate Detection with Current Amplicon-Based NGS Panels. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017, 12, 1582–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkiewicz, M.; Yeh, R.; Shu, C.A.; Hsiao, S.J.; Mansukhani, M.M.; Saqi, A.; Fernandes, H. Challenges in Amplicon-Based DNA NGS Identification of MET Exon 14 Skipping Events in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancers. J. Mol. Pathol. 2025, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.C.; Richardson, D.R. The c-MET oncoprotein: Function, mechanisms of degradation and its targeting by novel anti-cancer agents. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2020, 1864, 129650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.C.; Mirzapoiazova, T.; Won, B.M.; Zhu, L.; Srivastava, M.K.; Vokes, E.E.; Husain, A.N.; Batra, S.K.; Sharma, S.; Salgia, R. Differential responsiveness of MET inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer with altered CBL. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Zeng, R. Case Report: A 91-Year-Old Patient with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Harboring MET Y1003S Point Mutation. Front. Med. 2022, 8, 772998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.L.; Xu, Q.Q. MET Y1003S point mutation shows sensitivity to crizotinib in a patient with lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 2019, 130, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, M.; Salgia, R. The expanding role of the receptor tyrosine kinase MET as a therapeutic target in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 101983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Yu, Y.; Miao, D.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, J.; Shao, Z.; Jin, R.; Le, X.; Li, W.; Xia, Y. Targeting MET in NSCLC: An Ever-Expanding Territory. JTO Clin. Res. Rep. 2024, 5, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, P.K.; Felip, E.; Veillon, R.; Sakai, H.; Cortot, A.B.; Garassino, M.C.; Mazieres, J.; Viteri, S.; Senellart, H.; Van Meerbeeck, J.; et al. Tepotinib in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer with MET Exon 14 Skipping Mutations. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 931–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, U.; Singh, A.K.; Nathany, S.; Dewan, A.; Sharma, M.; Amrith, B.P.; Mehta, A.; Batra, V.; Noronha, V.; Prabhash, K. Real world experience with MET inhibitors in MET exon 14 skipping mutated non-small cell lung cancer: Largest Indian perspective. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolfo, C.; Malapelle, U.; Russo, A. Skipping or Not Skipping? That’s the Question! An Algorithm to Classify Novel MET Exon 14 Variants in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2023, 7, e2200674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, K.; Kyriazopoulou Panagiotopoulou, S.; McRae, J.F.; Darbandi, S.F.; Knowles, D.; Li, Y.I.; Kosmicki, J.A.; Arbelaez, J.; Cui, W.; Schwartz, G.B.; et al. Predicting Splicing from Primary Sequence with Deep Learning. Cell 2019, 176, 535–548.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosi, V.; Luca, A.; Milan, M.; Arigoni, M.; Benvenuti, S.; Cacchiarelli, D.; Cesana, M.; Riccardo, S.; Di Filippo, L.; Cordero, F.; et al. MET Exon 14 Skipping: A Case Study for the Detection of Genetic Variants in Cancer Driver Genes by Deep Learning. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Jakubowski, M.A.; Spildener, J.; Cheng, Y.W. Identification of Novel MET Exon 14 Skipping Variants in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients: A Prototype Workflow Involving in Silico Prediction and RT-PCR. Cancers 2022, 14, 4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanesyan, L.; Steenkamer, M.J.; Horstman, A.; Moelans, C.B.; Schouten, J.P.; Savola, S.P. Optimal Fixation Conditions and DNA Extraction Methods for MLPA Analysis on FFPE Tissue-Derived DNA. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2017, 147, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raponi, M.; Kralovicova, J.; Copson, E.; Divina, P.; Eccles, D.; Johnson, P.; Baralle, D.; Vorechovsky, I. Prediction of single-nucleotide substitutions that result in exon skipping: Identification of a splicing silencer in BRCA1 exon 6. Hum. Mutat. 2011, 32, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Urbanska, E.M.; Doktor, T.K.; Melchior, L.C.; Petersson, E.S.; Sørensen, J.B.; Santoni-Rugiu, E.; Andresen, B.S.; Grauslund, M. Improvement of Diagnostics in NSCLC Patients with MET Exon 14 Mutations Using Complementary DNA/RNA-NGS and Identification of Two Novel Exonic Splicing Mutations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010106

Urbanska EM, Doktor TK, Melchior LC, Petersson ES, Sørensen JB, Santoni-Rugiu E, Andresen BS, Grauslund M. Improvement of Diagnostics in NSCLC Patients with MET Exon 14 Mutations Using Complementary DNA/RNA-NGS and Identification of Two Novel Exonic Splicing Mutations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010106

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrbanska, Edyta Maria, Thomas Koed Doktor, Linea Cecilie Melchior, Eva Stampe Petersson, Jens Benn Sørensen, Eric Santoni-Rugiu, Brage Storstein Andresen, and Morten Grauslund. 2026. "Improvement of Diagnostics in NSCLC Patients with MET Exon 14 Mutations Using Complementary DNA/RNA-NGS and Identification of Two Novel Exonic Splicing Mutations" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010106

APA StyleUrbanska, E. M., Doktor, T. K., Melchior, L. C., Petersson, E. S., Sørensen, J. B., Santoni-Rugiu, E., Andresen, B. S., & Grauslund, M. (2026). Improvement of Diagnostics in NSCLC Patients with MET Exon 14 Mutations Using Complementary DNA/RNA-NGS and Identification of Two Novel Exonic Splicing Mutations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010106