Evaluation of Cytocompatibility and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Carboxyxanthones Selected by In Silico Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

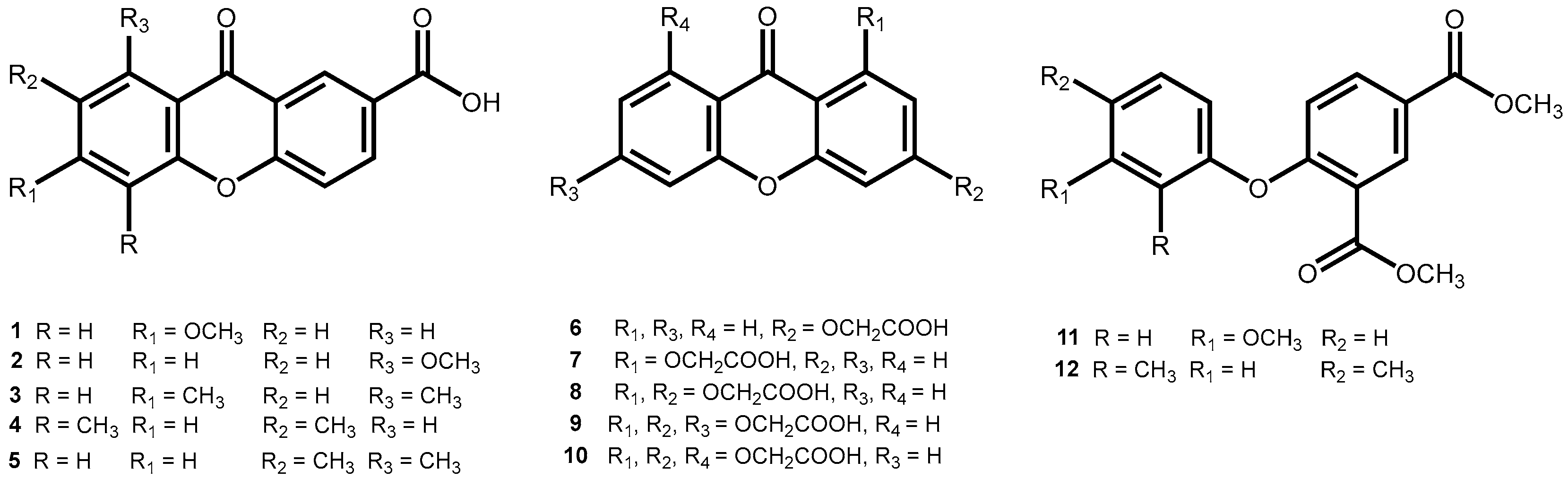

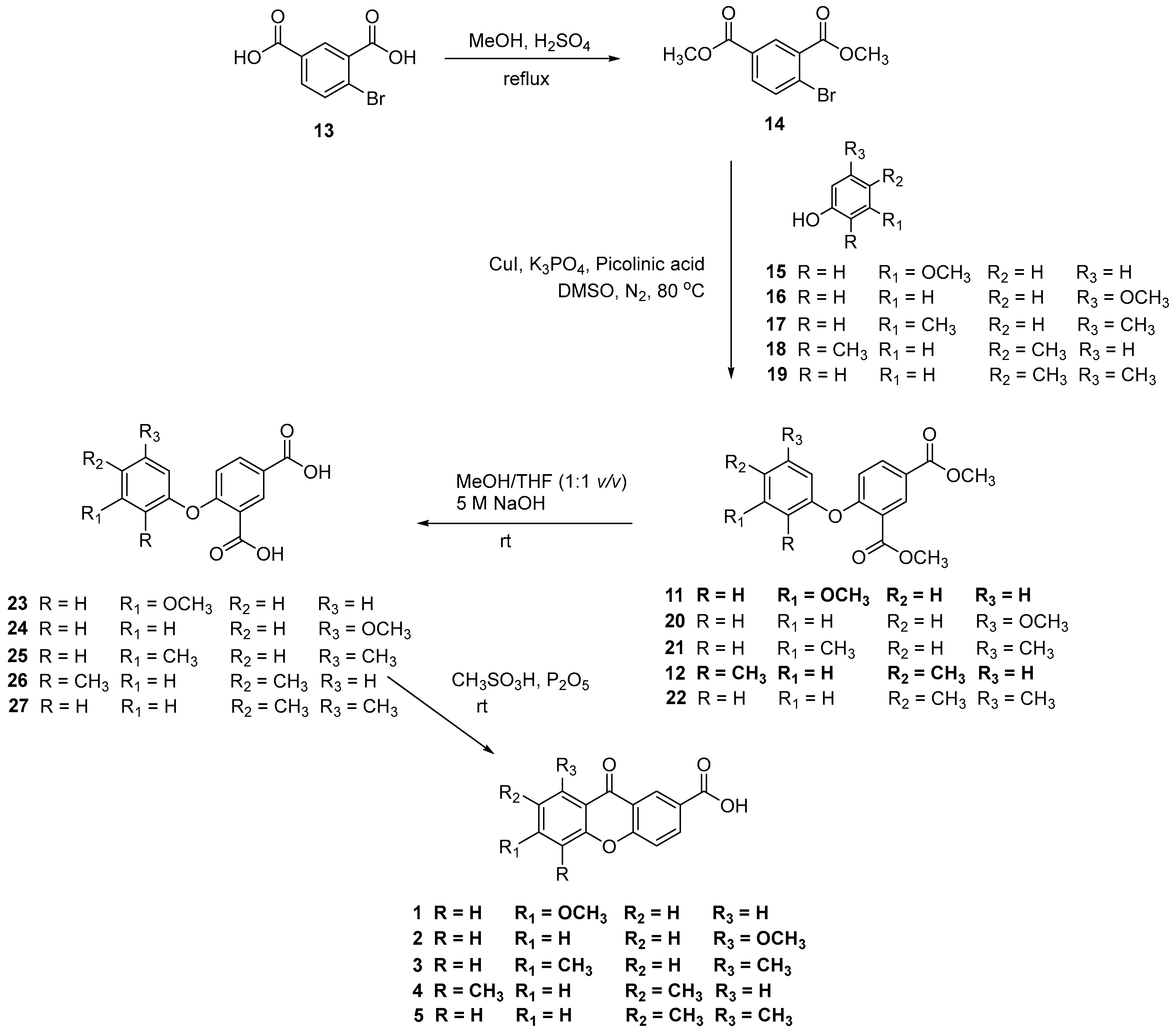

2.1. Synthesis of Carboxyxanthones

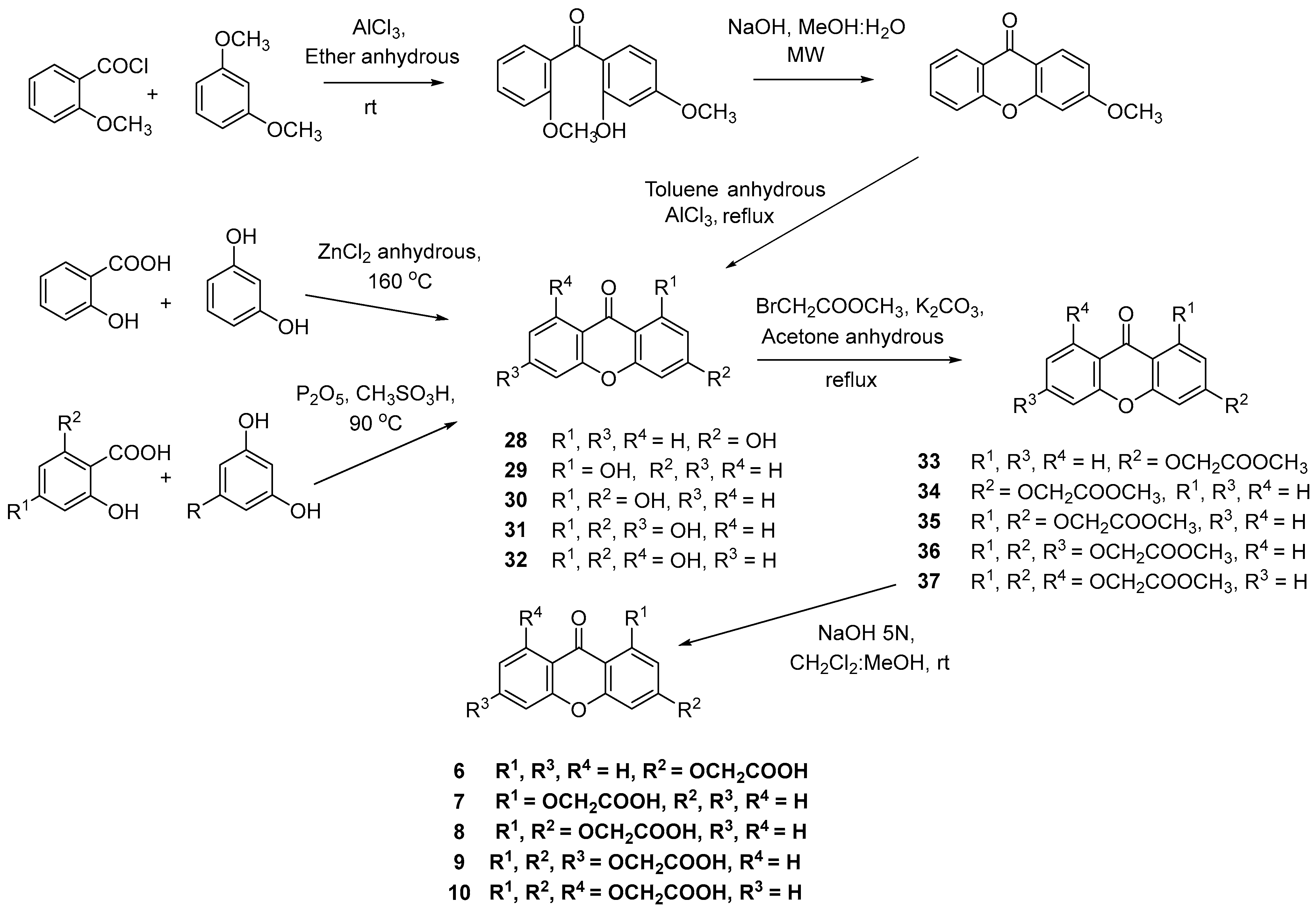

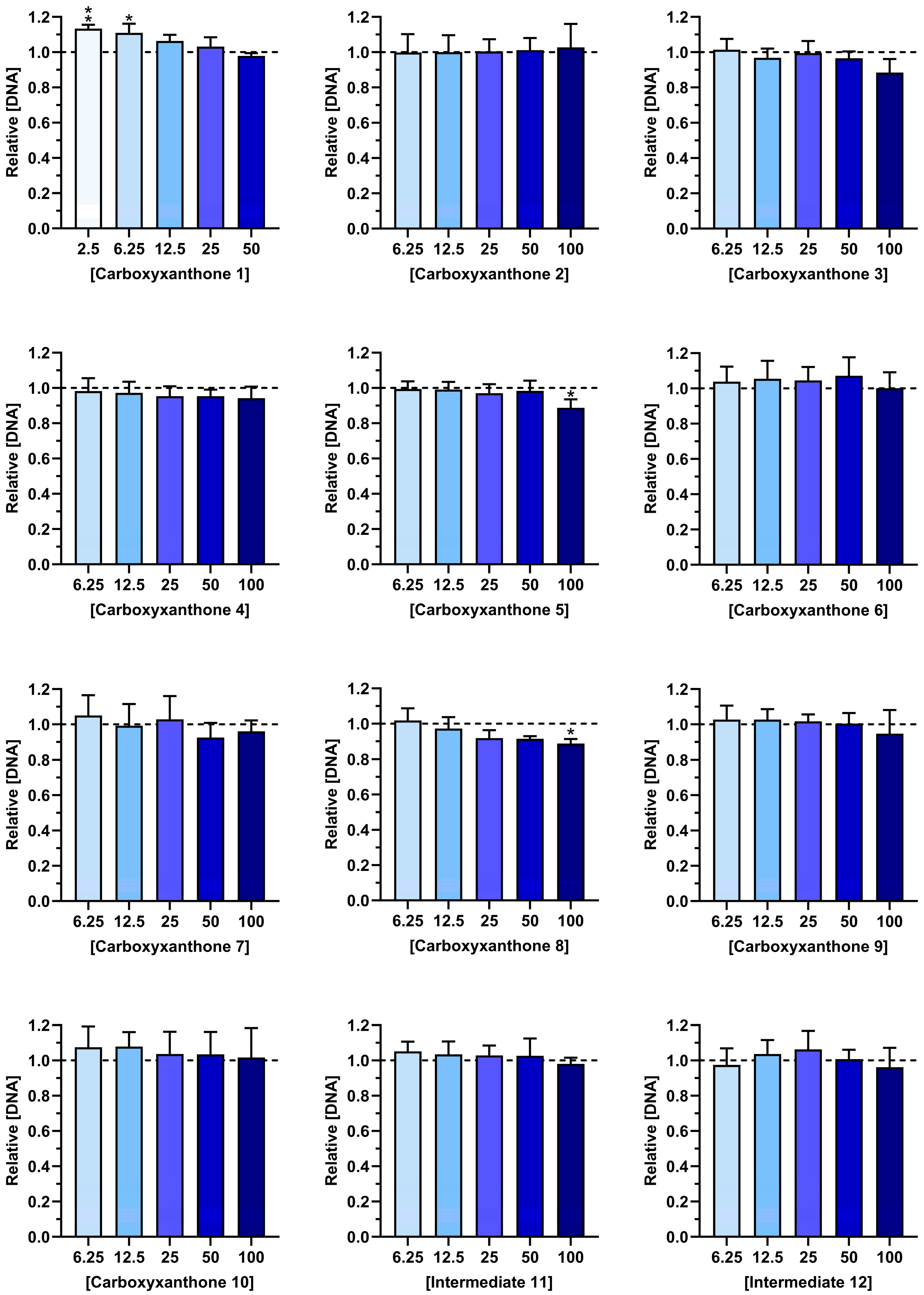

2.2. Cytocompatibility

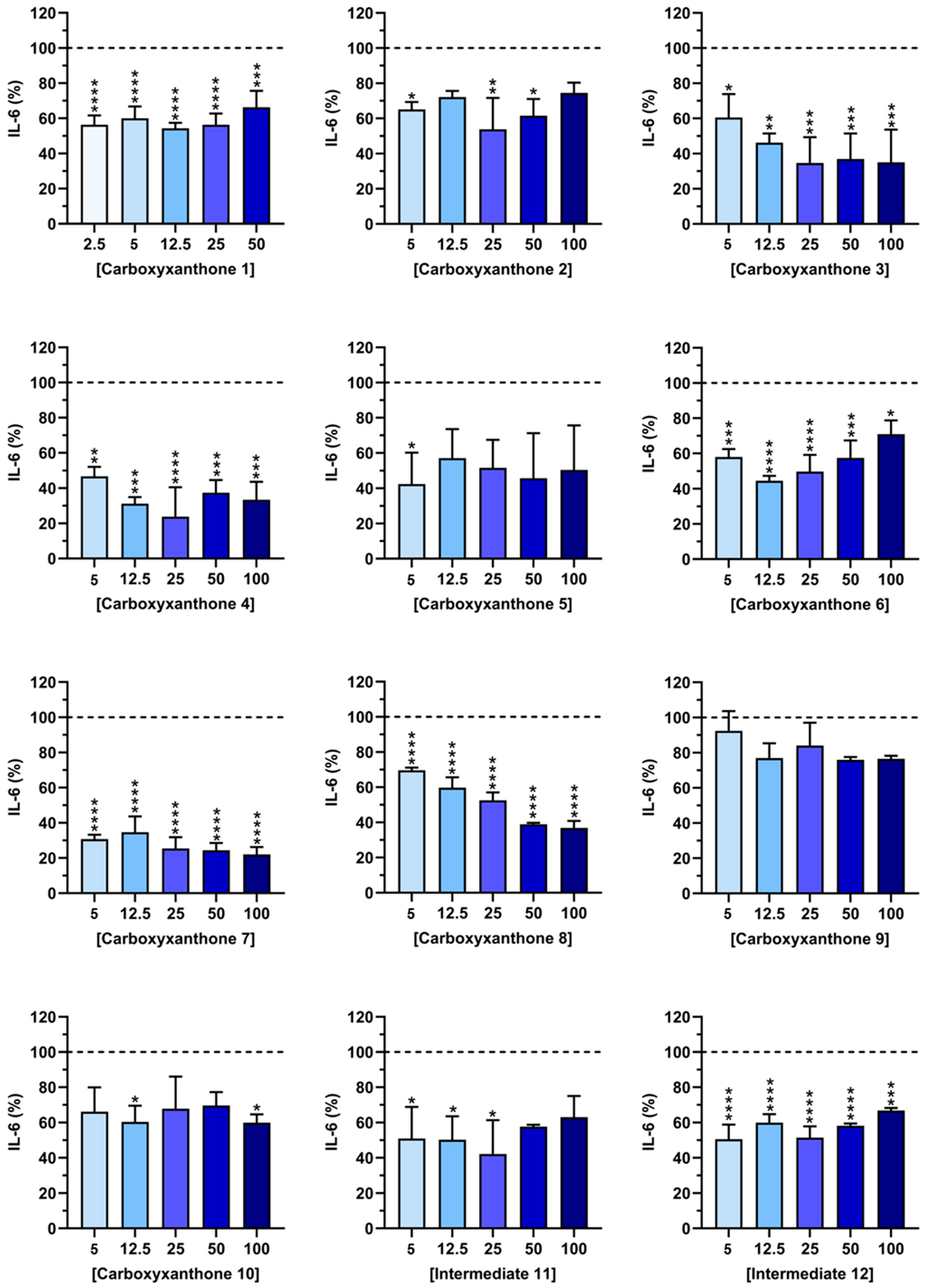

2.3. IL-6 Quantification

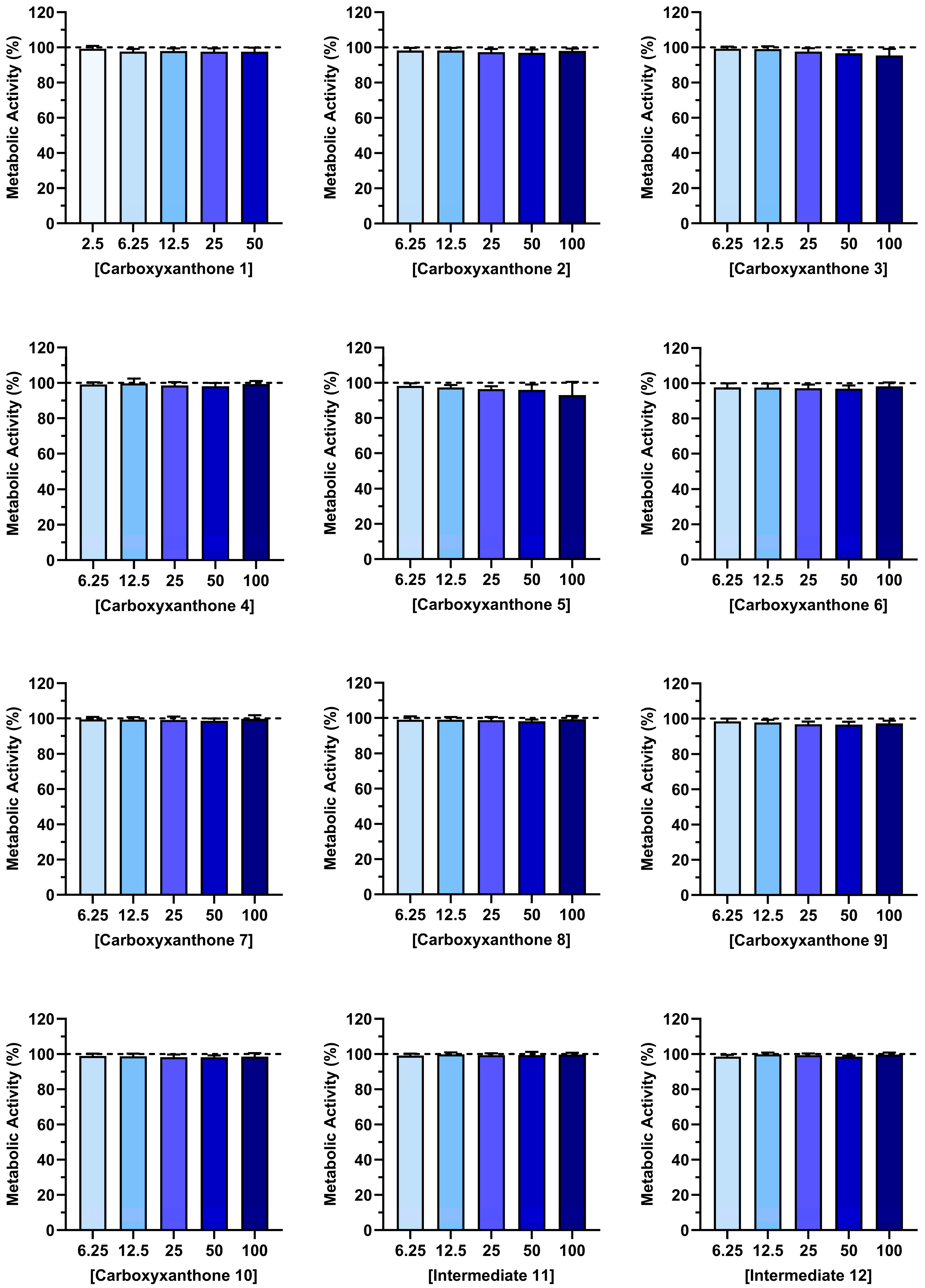

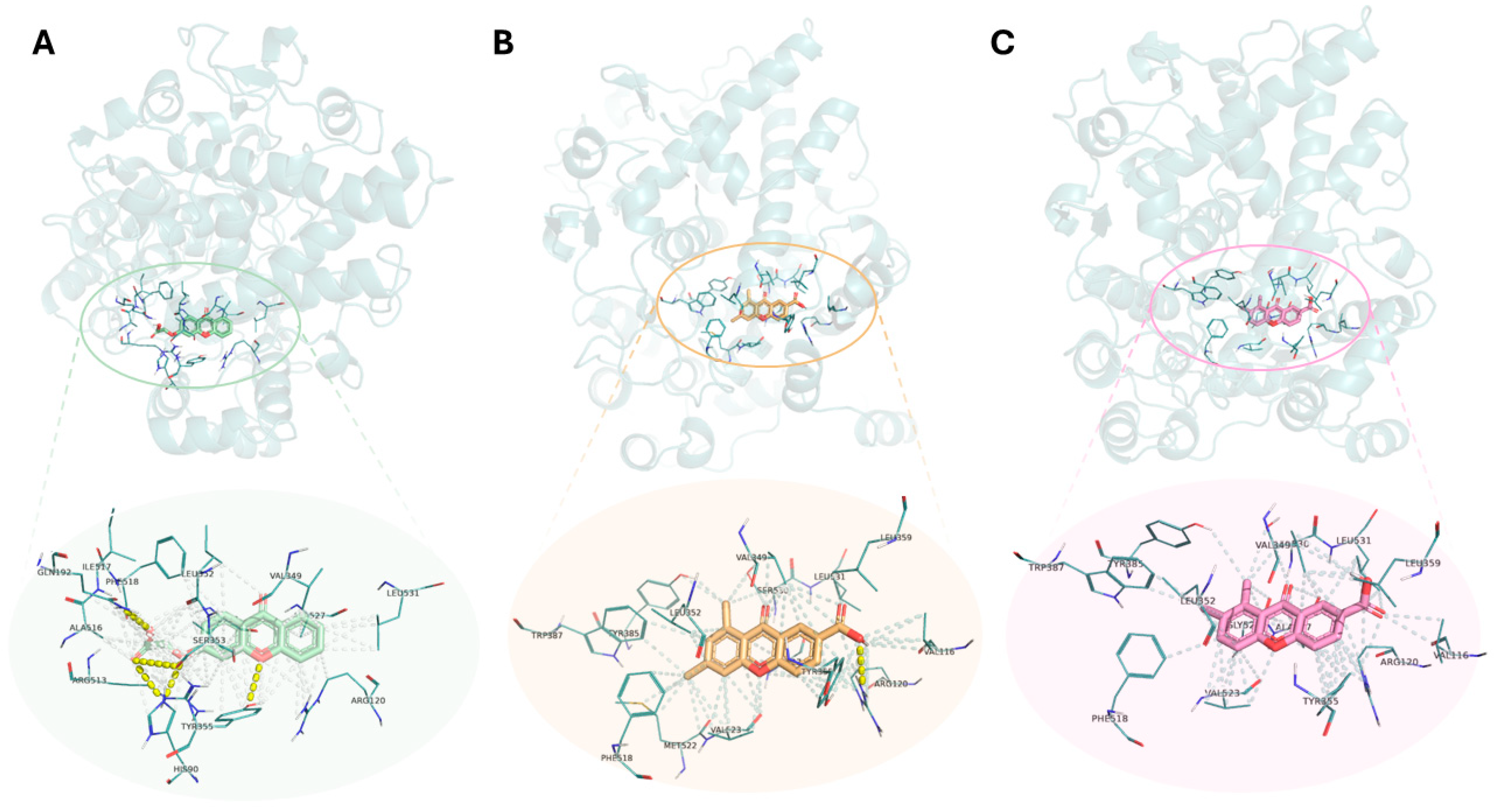

2.4. Structure-Based Virtual Screening

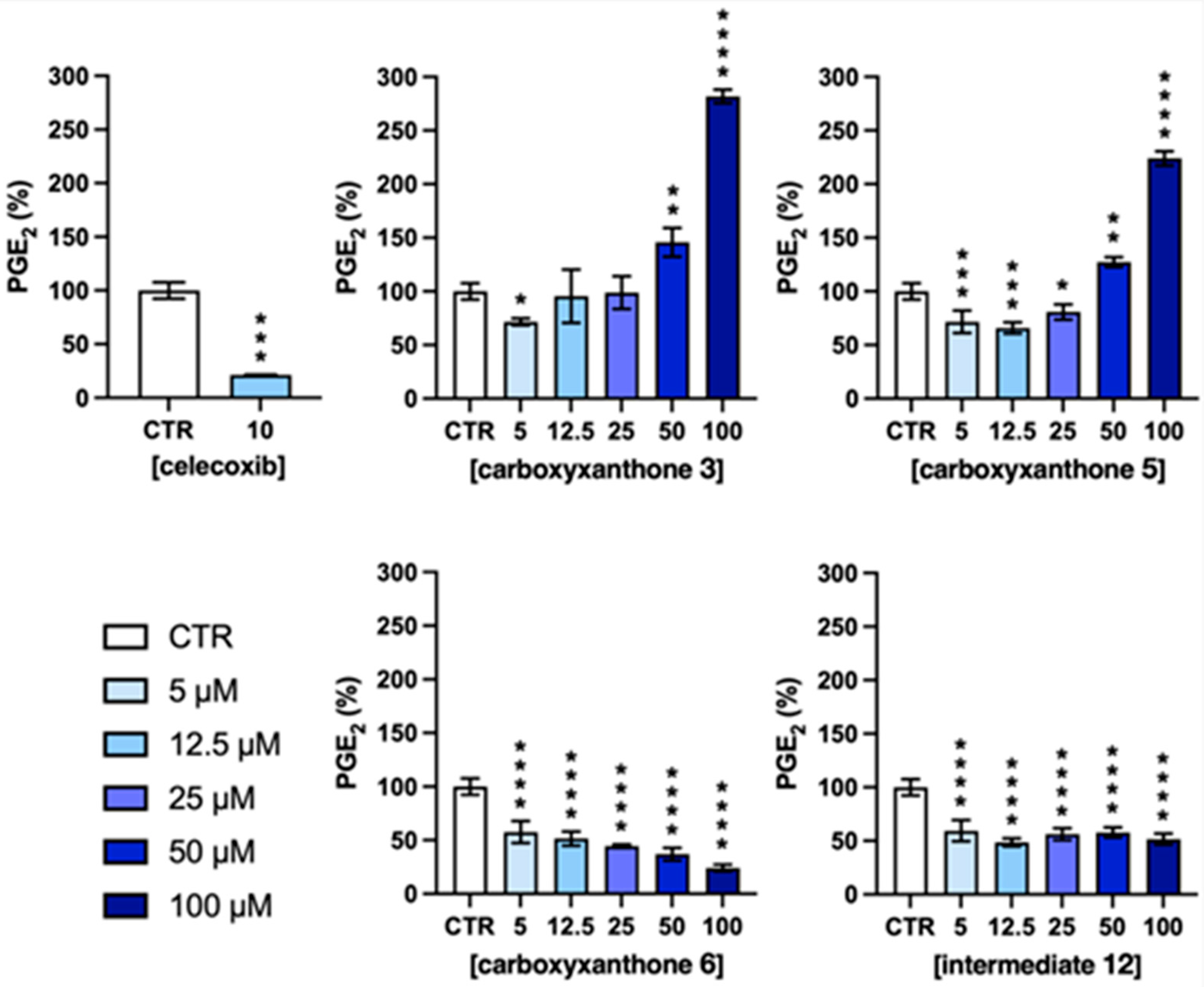

2.5. PGE2 Quantification

3. Methods and Materials

3.1. Synthesis

3.1.1. General

3.1.2. Synthesis of the carboxyxanthones 6-methoxy-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-2-carboxylic acid (1) and 8-methoxy-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-2-carboxylic acid (2), and intermediate dimethyl 4-(3-methoxyphenoxy)isophthalate (11)

3.1.3. Synthesis of the carboxyxanthone 6,8-dimethyl-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-2-carboxylic acid (3)

Synthesis of dimethyl 4-bromoisophthalate (14)

Synthesis of dimethyl 4-(3,5-dimethylphenoxy)isophthalate (21)

Synthesis of 4-(3,5-dimethylyphenoxy)isophthalic acid (25)

Intramolecular acylation: synthesis of 6,8-dimethyl-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-2-carboxylic acid (3)

Synthesis of the carboxyxanthone 5,7-dimethyl-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-2-carboxylic acid (4) and intermediate dimethyl 4-(2,4-dimethylphenoxy)isophthalate (12)

Synthesis of the carboxyxanthone 7,8-dimethyl-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-2-carboxylic acid (5)

Synthesis of dimethyl 4-(3,4-dimethylphenoxy)isophthalate (22)

Synthesis of 4-(3,4-dimethylphenoxy)isophthalic acid (27)

Intramolecular acylation: synthesis of 7,8-dimethyl-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-2-carboxylic acid (5)

Synthesis of the carboxyxanthone 2-((9-oxo-9H-xanthen-3-yl)oxy)acetic acid (6)

Synthesis of the carboxyxanthones 2-((9-oxo-9H-xanthen-1-yl)oxy)acetic acid (7), 2-((3-ethoxy-9-oxo-9H-xanthen-1-yl)oxy)acetic acid (8), 2,2′-((3-ethoxy-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-1,6-diyl)bis(oxy))diacetic acid (9) and 2-((8-((carboxyoxy)methyl)-3-ethoxy-9-oxo-9H-xanthen-1-yl)oxy)acetic acid (10)

3.2. Computational

3.2.1. Preparation of Ligands and Macromolecules

3.2.2. Docking

3.3. Biological Activity

3.3.1. Reagents

3.3.2. Compound Stock Solutions

3.3.3. Cytocompatibility and Anti-Inflammatory Activity

Cell Metabolic Activity and DNA Concentration

IL-6 and PGE2 Quantification

Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADMET | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity |

| bDMARDs | Biologic DMARDs |

| COX | Cyclooxigenase |

| csDMARDs | Conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte chemoattractant protein |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| RNS | Reactive Nitrogen Species |

| ROS | Reactive Oxigen Species |

| SAR | Structure-activity relationship |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor α |

| tsDMARDs | Targeted synthetic DMARDs |

| TXA2 | Thromboxane |

References

- Fioranelli, M.; Roccia, M.G.; Flavin, D.; Cota, L. Regulation of Inflammatory Reaction in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medzhitov, R. Origin and Physiological Roles of Inflammation. Nature 2008, 454, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.F.; Reis, R.L.; Ferreira, H.; Neves, N.M. Plant-Derived Bioactive Compounds as Key Players in the Modulation of Immune-Related Conditions. Phytochem. Rev. 2025, 24, 343–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, S.; Acuña, V.; Ceriani, R.; Cavieres, M.F.; Weinstein-Oppenheimer, C.R.; Campos-Estrada, C. Involvement of Inflammation and Its Resolution in Disease and Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, E.C.; Tareq, H.S.; Suggs, L.J. Inflammation: A Matter of Immune Cell Life and Death. npj Biomed. Innov. 2025, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netea, M.G.; Balkwill, F.; Chonchol, M.; Cominelli, F.; Donath, M.Y.; Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J.; Golenbock, D.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Heneka, M.T.; Hoffman, H.M.; et al. A Guiding Map for Inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 826–831, Correction in Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 254. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-020-00846-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chovatiya, R.; Medzhitov, R. Stress, Inflammation, and Defense of Homeostasis. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haley, R.M.; von Recum, H.A. Localized and Targeted Delivery of NSAIDs for Treatment of Inflammation: A Review. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019, 244, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iezzi, A.; Ferri, C.; Mezzetti, A.; Cipollone, F. COX-2: Friend or Foe? Curr. Pharm. Des. 2007, 13, 1715–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, N.A.; Ahmed, E.M.; Tharwat, T.; Mahmoud, Z. NSAIDs between Past and Present; a Long Journey towards an Ideal COX-2 Inhibitor Lead. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 30647–30661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, C.-O.; Hjemdahl, P. Lessons from 20 Years with COX-2 Inhibitors: Importance of Dose–Response Considerations and Fair Play in Comparative Trials. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 292, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, T.; Lafforgue, P.; Pham, T. NSAID: Current Limits to Prescription. Joint Bone Spine 2024, 91, 105685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarberg, B.; Gibofsky, A. Need to Develop New Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Formulations. Clin. Ther. 2012, 34, 1954–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shagufta; Ahmad, I. Recent Insight into the Biological Activities of Synthetic Xanthone Derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 116, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Palmeira, A.; Ramos, I.I.; Carneiro, C.; Afonso, C.; Tiritan, M.E.; Cidade, H.; Pinto, P.C.A.G.; Saraiva, M.L.M.F.S.; Reis, S.; et al. Chiral Derivatives of Xanthones: Investigation of the Effect of Enantioselectivity on Inhibition of Cyclooxygenases (COX-1 and COX-2) and Binding Interaction with Human Serum Albumin. Pharmaceuticals 2017, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos Miguel Goncalves, A.; Carlos Manuel Magalhaes, A.; Madalena Maria Magalhaes, P. Routes to Xanthones: An Update on the Synthetic Approaches. Curr. Org. Chem. 2012, 16, 2818–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.M.M.; Palmeira, A.; Fernandes, C.; Resende, D.I.S.P.; Sousa, E.; Cidade, H.; Tiritan, M.E.; Correia-da-Silva, M.; Cravo, S. From Natural Products to New Synthetic Small Molecules: A Journey through the World of Xanthones. Molecules 2021, 26, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Lu, X.; Gan, L.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, L. Xanthones, a Promising Anti-Inflammatory Scaffold: Structure, Activity, and Drug Likeness Analysis. Molecules 2020, 25, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunakaran, T.; Ee, G.C.L.; Ismail, I.S.; Nor, S.M.M.; Zamakshshari, N.H. Acetyl- and O-Alkyl- Derivatives of β-Mangostin from Garcinia Mangostana and Their Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 1390–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, Q.; Sun, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lin, L. 1,3,6,7-Tetrahydroxy-8-Prenylxanthone Ameliorates Inflammatory Responses Resulting from the Paracrine Interaction of Adipocytes and Macrophages. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 1590–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Li, D.; Wang, A.; Dong, Z.; Yin, S.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, Y.; Li, L.; Lin, L. Nitric Oxide Inhibitory Xanthones from the Pericarps of Garcinia Mangostana. Phytochemistry 2016, 131, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, G.S.; Lee, D.S.; Kim, Y.C. Cudratricusxanthone A from Cudrania Tricuspidata Suppresses Pro-Inflammatory Mediators through Expression of Anti-Inflammatory Heme Oxygenase-1 in RAW264.7 Macrophages. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2009, 9, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crockett, S.L.; Poller, B.; Tabanca, N.; Pferschy-Wenzig, E.M.; Kunert, O.; Wedge, D.E.; Bucar, F. Bioactive Xanthones from the Roots of Hypericum Perforatum (Common St John’s Wort). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenfeld, E.M.; Kong, Y.; Langenfeld, J. Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 Stimulation of Tumor Growth Involves the Activation of Smad-1/5. Oncogene 2006, 25, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asirvatham, S.; Dhokchawle, B.V.; Tauro, S.J. Quantitative Structure Activity Relationships Studies of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: A Review. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 3948–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.; Veloso, C.; Fernandes, C.; Tiritan, M.E.; Pinto, M.M.M. Carboxyxanthones: Bioactive Agents and Molecular Scaffold for Synthesis of Analogues and Derivatives. Molecules 2019, 24, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, D.R.P.; Magalhães, Á.F.; Soares, J.X.; Pinto, J.; Azevedo, C.M.G.; Vieira, S.; Henriques, A.; Ferreira, H.; Neves, N.; Bousbaa, H.; et al. Yicathins B and C and Analogues: Total Synthesis, Lipophilicity and Biological Activities. ChemMedChem 2020, 15, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.F.; Araújo, J.; Gonçalves, V.M.F.; Fernandes, C.; Pinto, M.; Ferreira, H.; Neves, N.M.; Tiritan, M.E. Synthesis and Anti-Inflammatory Evaluation of a Library of Chiral Derivatives of Xanthones Conjugated with Proteinogenic Amino Acids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, T. IL-6 in Inflammation, Autoimmunity and Cancer. Int. Immunol. 2021, 33, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phyo, Y.Z.; Teixeira, J.; Tiritan, M.E.; Cravo, S.; Palmeira, A.; Gales, L.; Silva, A.M.S.; Pinto, M.M.M.; Kijjoa, A.; Fernandes, C. New Chiral Stationary Phases for Liquid Chromatography Based on Small Molecules: Development, Enantioresolution Evaluation and Chiral Recognition Mechanisms. Chirality 2020, 32, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Masawang, K.; Tiritan, M.E.; Sousa, E.; de Lima, V.; Afonso, C.; Bousbaa, H.; Sudprasert, W.; Pedro, M.; Pinto, M.M. New Chiral Derivatives of Xanthones: Synthesis and Investigation of Enantioselectivity as Inhibitors of Growth of Human Tumor Cell Lines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 1049–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, M.L.; Marques, S.; Silva, A.S.; Freitas, B.; Silva, P.M.A.; Pedrosa, J.; De Marco, P.; Bousbaa, H.; Fernandes, C.; Tiritan, M.E.; et al. Synthesis of New Chiral Derivatives of Xanthones with Enantioselective Effect on Tumor Cell Growth and DNA Crosslinking. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 10285–10291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Oliveira, L.; Tiritan, M.E.; Leitao, L.; Pozzi, A.; Noronha-Matos, J.B.; Correia-de-Sá, P.; Pinto, M.M. Synthesis of New Chiral Xanthone Derivatives Acting as Nerve Conduction Blockers in the Rat Sciatic Nerve. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, D.; Buchwald, S.L. Cu-Catalyzed Arylation of Phenols: Synthesis of Sterically Hindered and Heteroaryl Diaryl Ethers. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 1791–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, E.; Paiva, A.; Nazareth, N.; Gales, L.; Damas, A.M.; Nascimento, M.S.J.; Pinto, M. Bromoalkoxyxanthones as Promising Antitumor Agents: Synthesis, Crystal Structure and Effect on Human Tumor Cell Lines. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 3830–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, R.K.M.; Naiksatam, P.; Johnson, F.; Rajagopalan, R.; Watts, P.C.; Cricchio, R.; Borras, S. Thermorubin II. 1,3-Dihydroxy-9H-Xanthones and 1,3-Dihydroxy-9H-Xanthenes. New Methods of Synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 1986, 51, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, I.; Puthongking, P.; Cravo, S.; Palmeira, A.; Cidade, H.; Pinto, M.; Sousa, E. Xanthone and Flavone Derivatives as Dual Agents with Acetylcholinesterase Inhibition and Antioxidant Activity as Potential Anti-Alzheimer Agents. J. Chem. 2017, 2017, 8587260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.K.; Tho, L.-Y.; Lim, Y.M.; Shah, S.A.A.; Weber, J.-F.F. Synthesis of 1,3,6-Trioxygenated Prenylated Xanthone Derivatives as Potential Antitumor Agents. Lett. Org. Chem. 2012, 9, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiloglu, S.; Sari, G.; Ozdal, T.; Capanoglu, E. Guidelines for Cell Viability Assays. Food Front. 2020, 1, 332–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10993-5; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices—Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Turner, M.D.; Nedjai, B.; Hurst, T.; Pennington, D.J. Cytokines and Chemokines: At the Crossroads of Cell Signalling and Inflammatory Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2014, 1843, 2563–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Seukep, A.J.; Guo, M. Recent Advances in Molecular Docking for the Research and Discovery of Potential Marine Drugs. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinzi, L.; Rastelli, G. Molecular Docking: Shifting Paradigms in Drug Discovery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atukorala, I.; Hunter, D.J. Valdecoxib: The Rise and Fall of a COX-2 Inhibitor. Expert. Opin. Pharmacother. 2013, 14, 1077–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantsar, T.; Poso, A. Binding Affinity via Docking: Fact and Fiction. Molecules 2018, 23, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ryn, J.; Trummlitz, G.; Pairet, M. COX-2 Selectivity and Inflammatory Processes. Curr. Med. Chem. 2000, 7, 1145–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.L.; Dewitt, D.L.; Garavito, R.M. Cyclooxygenases: Structural, Cellular, and Molecular Biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000, 69, 145–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurumbail, R.G.; Stevens, A.M.; Gierse, J.K.; McDonald, J.J.; Stegeman, R.A.; Pak, J.Y.; Gildehaus, D.; Iyashiro, J.M.; Penning, T.D.; Seibert, K.; et al. Structural Basis for Selective Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase-2 by Anti-Inflammatory Agents. Nature 1996, 384, 644–648, Erratum in Nature 1997, 6, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed, M.A.-A.; Abdel-Aziz, N.I.; Abdel-Aziz, A.A.-M.; El-Azab, A.S.; ElTahir, K.E.H. Synthesis, Biological Evaluation and Molecular Modeling Study of Pyrazole and Pyrazoline Derivatives as Selective COX-2 Inhibitors and Anti-Inflammatory Agents. Part 2. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 3306–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichai, V.; Suyarnsesthakorn, C.; Pittayakhajonwut, D.; Sriklung, K.; Kirtikara, K. Positive Feedback Regulation of COX-2 Expression by Prostaglandin Metabolites. Inflamm. Res. 2005, 54, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowda, R.; Kardos, G.; Sharma, A.; Singh, S.; Robertson, G.P. Nanoparticle-Based Celecoxib and Plumbagin for the Synergistic Treatment of Melanoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Muñoz, M.D.; Osma-García, I.C.; Fresno, M.; Íñiguez, M.A.; De Biología Molecular, C.; Ochoa, S.; Cabrera, N. Involvement of PGE 2 and Cyclic AMP Signaling Pathway in the Up-Regulation of COX-2 and MPGES-1 Expression in LPS-Activated Macrophages. Running Title: Regulation of COX-2 and MPGES-1 by PGE 2. Biochem. J. 2012, 443, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mura, C.; Beharka, A.A.; Nim Han, S.; Eric Paulson, K.; Hwang, D.; Nikbin Meydani, S. Age-Associated Increase in PGE 2 Synthesis and COX Activity in Murine Macrophages Is Reversed by Vitamin E. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 1998, 275, C661–C668. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, S.J.; Prickril, B.; Rasooly, A. Mechanisms of Phytonutrient Modulation of Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and Inflammation Related to Cancer. Nutr. Cancer 2018, 70, 350–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.P.; Peng, Y.B.; Zhang, Y.F.; Wang, Y.; Yu, W.R.; Yao, M.; Fu, X.J. Reactive Oxygen Species Mediated Prostaglandin E2 Contributes to Acute Response of Epithelial Injury. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 4123854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tithof, P.K.; Roberts, M.P.; Guan, W.; Elgayyar, M.; Godkin, J.D. Distinct Phospholipase A2 Enzymes Regulate Prostaglandin E2 and F2alpha Production by Bovine Endometrial Epithelial Cells. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2007, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, F.; Suzuki, T.; Gordon, O.N.; Golding, D.; Okuno, T.; Giménez-Bastida, J.A.; Yokomizo, T.; Schneider, C. Biosynthetic Crossover of 5-Lipoxygenase and Cyclooxygenase-2 Yields 5-Hydroxy-PGE2and 5-Hydroxy-PGD2. JACS Au 2021, 1, 1380–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Qian, C.; Lin, J.; Liu, B. Cyclooxygenase-2-Prostaglandin E2 Pathway: A Key Player in Tumor-Associated Immune Cells. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1099811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casewit, C.J.; Colwell, K.S.; Rappe, A.K. Application of a Universal Force Field to Main Group Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 10046–10053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, P.W.; Prlić, A.; Bi, C.; Bluhm, W.F.; Christie, C.H.; Dutta, S.; Green, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Westbrook, J.D.; Woo, J.; et al. The RCSB Protein Data Bank: Views of Structural Biology for Basic and Applied Research and Education. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D345–D356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeliger, D.; de Groot, B.L. Ligand Docking and Binding Site Analysis with PyMOL and Autodock/Vina. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2010, 24, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compounds | Number of Polar Interactions | Interacting Groups | Amino Acids/ Bond Length (Å) | Binding Energy Score (kcal/mol) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COX-1 | COX-2 | COX-1 | COX-2 | COX-1 | COX-2 | COX-1 | COX-2 | |

| Diclofenac | 1 | 0 | OH (carboxylic acid) | - | Arg 120 (3.15) | - | −7.1 | −8.3 |

| Indomethacin | 2 | 4 | O (amide) | O (carboxylic acid) | Arg 120 (2.86) | His 90 (3.34) | −8.0 | −8.3 |

| OH (hydroxyl) | OH (carboxylic acid) | Leu 352 (2.98) | Leu 352 (3.07) | |||||

| O (amide) | Tyr 355 (2.61) | |||||||

| O (carboxylic acid) | Arg 513 (3.11) | |||||||

| Naproxen | 1 | 2 | OH (carboxylic acid) | O (ether) | Arg 120 (3.03) | Arg 120 (3.06) | −8.2 | −8.1 |

| OH (carboxylic acid) | Gly 526 (3.13) | |||||||

| Piroxicam | 3 | 1 | O (amide) | O (sulfate) | Val 349 (3.16) | Ser 530 (2.64) | −7.1 | −8.0 |

| O (sulfonyl) | Ile 523 (2.46) | |||||||

| O (sulfonyl) | Ala 527 (2.70) | |||||||

| Celecoxib | - | 4 | - | O (sulfonamine) | - | His 90 (3.18) | - | −10.0 |

| O (sulfonamine) | His 90 (3.50) | |||||||

| N (sulfonamine) | Leu 352 (3.06) | |||||||

| O (sulfonamine) | Arg 513 (3.27) | |||||||

| Valdecoxib | - | 2 | - | O (sulfonamine) | - | Tyr 355 (2.90) | - | −9.0 |

| O (isoxazole) | Tyr 385 (2.71) | |||||||

| (S)-Ibuprofen | 1 | 0 | OH (carboxylic acid) | - | Arg 120 (3.11) | - | −7.7 | −7.4 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | O (diaryl ether) | O (carboxylic acid) | Tyr 355 (2.91) | Arg 120 (3.26) | −8.1 | −8.4 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | - | O (diaryl ether) | - | Ser 530 (3.41) | −8.3 | −8.6 |

| 3 | 0 | 1 | - | OH (carboxylic acid) | - | Arg 120 (3.26) | −8.4 | −9.0 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | O (ketone) | - | Ser 530 (2.92) | - | −8.7 | −8.5 |

| 5 | 2 | 0 | O (carboxylic acid) | - | Tyr 385 (2.92) | - | −8.2 | −9.0 |

| O (ketone) | Ser 530 (2.93) | |||||||

| 6 | 1 | 5 | O (carboxylic acid) | OH (carboxylic acid) | His 90 (3.14) | His 90 (2.97) | −8.6 | −9.4 |

| O (carboxylic acid) | His 90 (3.24) | |||||||

| O (ether) | Gln 192 (3.00) | |||||||

| O (carboxylic acid) | Ser 533 (3.49) | |||||||

| O (diaryl ether) | Tyr 355 (2.93) | |||||||

| 7 | 1 | 0 | O (ketone) | - | Ser 530 (3.20) | - | −8.8 | −8.7 |

| 8 | 1 | 6 | O (ketone) | O (carboxylic acid) | Tyr 355 (3.17) | His 90 (3.10) | −8.6 | −8.9 |

| OH (carboxylic acid) | Gln 192 (2.98) | |||||||

| OH (carboxylic acid) | Leu 352 (3.08) | |||||||

| O (ether) | Leu 352 (3.10) | |||||||

| O (carboxylic acid) | Ser 353 (3.37) | |||||||

| O (diaryl ether) | Tyr 355 (3.07) | |||||||

| 9 | 1 | 3 | O (ketone) | O (ether) | Tyr 355 (3.21) | His 90 (2.73) | −7.4 | −8.3 |

| OH (carboxylic acid) | Leu 352 (2.90) | |||||||

| O (diaryl ether) | Tyr 355 (2.74) | |||||||

| 10 | 5 | 5 | OH (carboxylic acid) | O (carboxylic acid) | His 90 (2.93) | His 90 (3.07) | −6.1 | −8.7 |

| O (ketone) | O (ether) | Arg 120 (3.06) | His 90 (3.20) | |||||

| O (carboxylic acid) | O (carboxylic acid) | Tyr 385 (2.73) | Gln 192 (2.99) | |||||

| O (ether) | O (carboxylic acid) | Tyr 385 (2.80) | Ser 353 (3.47) | |||||

| O (carboxylic acid) | O (diaryl ether) | Ser 530 (3.01) | Tyr 355 (2.94) | |||||

| 11 | 1 | 3 | O (ester) | O (ester) | Arg 120 (2.77) | His 90 (3.07) | −8.8 | −8.9 |

| O (ester) | Arg 120 (2.97) | |||||||

| O (ether) | Leu 352 (3.17) | |||||||

| 12 | 2 | 2 | O (ester) | O (ester) | Arg 120 (2.80) | His 90 (3.33) | −7.6 | −9.1 |

| O (ester) | O (ester) | Tyr 355 (3.24) | Arg 120 (2.97) | |||||

| Celecoxib | Carboxyxanthone 3 | Carboxyxanthone 5 | Carboxyxanthone 6 | Intermediate 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| His 90 | - | - | His 90 | His 90 |

| Val 116 | Val 116 | Val 116 | - | - |

| Arg 120 | Arg 120 | Arg 120 | Arg 120 | Arg 120 |

| Gln 192 | - | - | Gln 192 | - |

| Val 349 | Val 349 | Val 349 | Val 349 | Val 349 |

| Leu 352 | Leu 352 | Leu 352 | Leu 352 | Leu 352 |

| Ser 353 | - | - | Ser 353 | Ser 353 |

| Tyr 355 | Tyr 355 | Tyr 355 | Tyr 355 | Tyr 355 |

| - | Leu 359 | Leu 359 | - | - |

| Phe 381 | - | - | - | - |

| Leu 384 | ||||

| Tyr 385 | Tyr 385 | Tyr 385 | - | Tyr 385 |

| Trp 387 | Trp 387 | Trp 387 | - | Trp 387 |

| Arg 513 * | - | - | Arg 513 * | Arg 513 * |

| Ala 516 * | - | - | Ala 516 * | - |

| Ile 517 | - | - | Ile 517 | - |

| Phe 518 | Phe 518 | Phe 518 | Phe 518 | - |

| Val 523 * | Val 523 * | Val 523 * | Val 523 * | Val 523 * |

| Gly 526 | - | Gly 526 | - | Gly 526 |

| Ala 527 | Ala 527 | Ala 527 | Ala 527 | 527 |

| Ser 530 | Ser 530 | Ser 530 | - | Ser 530 |

| Leu 531 | Leu 531 | Leu 531 | Leu 531 | Leu 531 |

—H-bond;

—H-bond;  —Permanent dipole interaction;

—Permanent dipole interaction;  —Hydrophobic interaction.

—Hydrophobic interaction.Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pereira, R.F.; Amoedo-Leite, C.; Gimondi, S.; Vieira, S.F.; Handel, J.; Palmeira, A.; Tiritan, M.E.; Pinto, M.M.M.; Neves, N.M.; Ferreira, H.; et al. Evaluation of Cytocompatibility and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Carboxyxanthones Selected by In Silico Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010110

Pereira RF, Amoedo-Leite C, Gimondi S, Vieira SF, Handel J, Palmeira A, Tiritan ME, Pinto MMM, Neves NM, Ferreira H, et al. Evaluation of Cytocompatibility and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Carboxyxanthones Selected by In Silico Studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010110

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira, Ricardo F., Catarina Amoedo-Leite, Sara Gimondi, Sara F. Vieira, João Handel, Andreia Palmeira, Maria Elizabeth Tiritan, Madalena M. M. Pinto, Nuno M. Neves, Helena Ferreira, and et al. 2026. "Evaluation of Cytocompatibility and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Carboxyxanthones Selected by In Silico Studies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010110

APA StylePereira, R. F., Amoedo-Leite, C., Gimondi, S., Vieira, S. F., Handel, J., Palmeira, A., Tiritan, M. E., Pinto, M. M. M., Neves, N. M., Ferreira, H., & Fernandes, C. (2026). Evaluation of Cytocompatibility and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Carboxyxanthones Selected by In Silico Studies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010110

_Kim.png)