Identification of Novel Regulators of Fruit Sugar Accumulation Based on Transcriptome and WGCNA in Citrus sinensis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Fruit Morphology and Sugar Content in the Ganmi Navel Orange

2.2. Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) in the Pulps of Ganmi and Newhall Navel Oranges

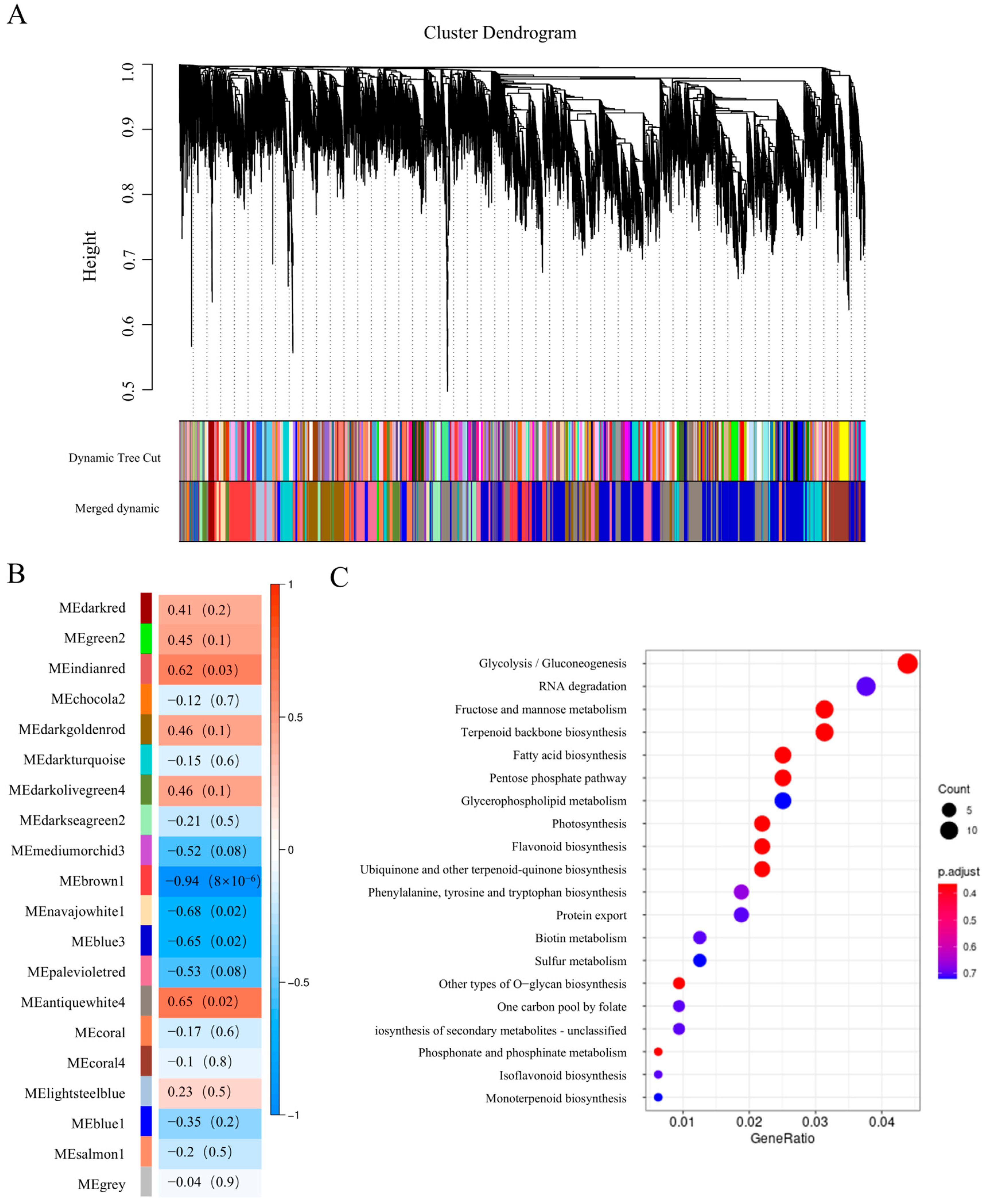

2.3. Co-Expression Network Analysis

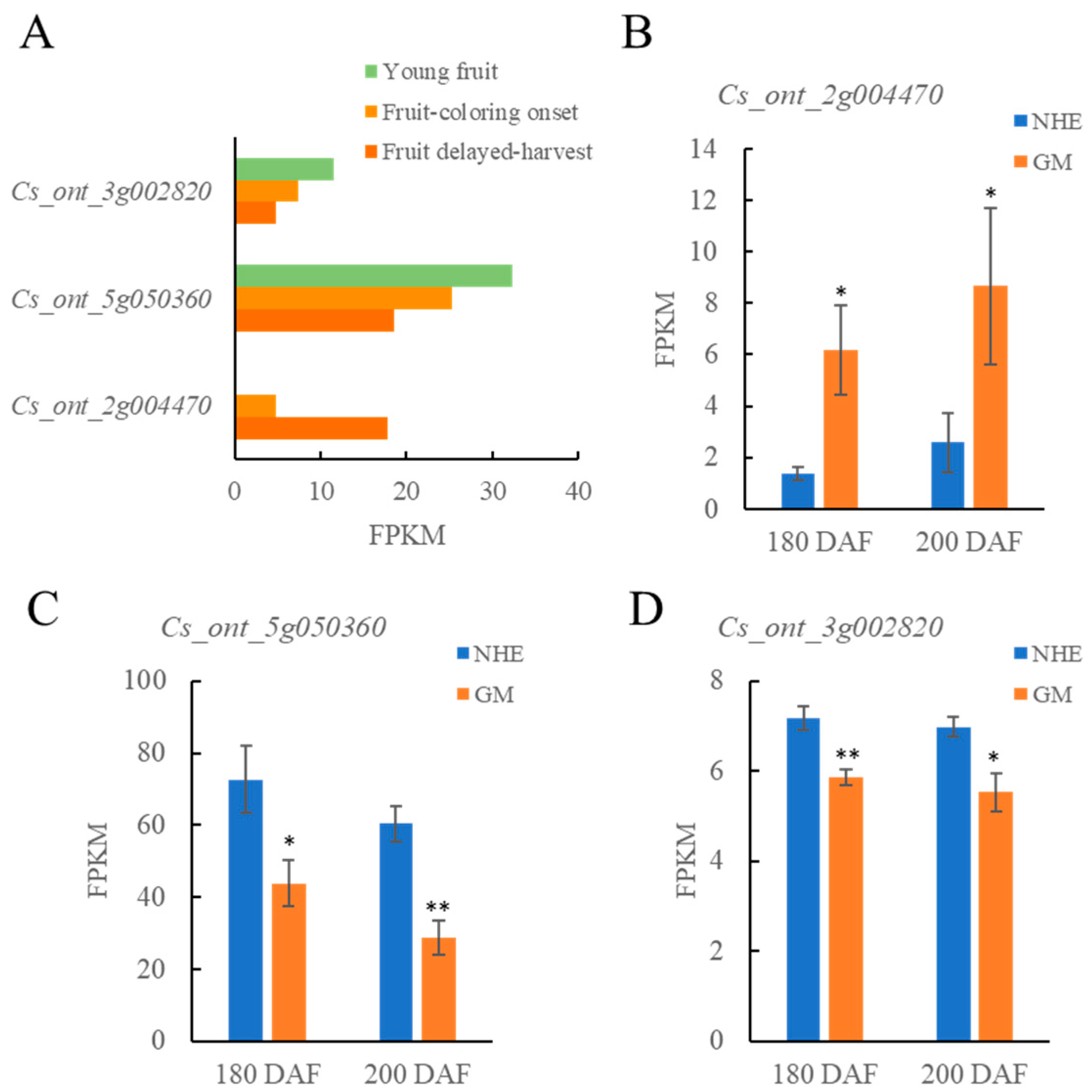

2.4. Screening of Key Genes in Relevant Modules

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials

4.2. Measurement of Flesh Soluble Solids Content

4.3. RNA Preparation

4.4. RNA-Seq Analysis

4.5. WGCNA

4.6. Expression Analysis of the Candidate Key Genes

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dia, M.; Wehner, T.C.; Perkins-Veazie, P.; Hassell, R.; Price, D.S.; Boyhan, G.E.; Olson, S.M.; King, S.R.; Davis, A.R.; Tolla, G.E.; et al. Stability of fruit quality traits in diverse watermelon cultivars tested in multiple environments. Hortic. Res. 2016, 3, 16066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.X.; Sun, H.Q.; Wang, Y.F.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.P. Effects of water stress on quality and sugar metabolism in ‘Gala’ apple fruit. Hortic. Plant J. 2023, 9, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, T.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Fang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Peng, F.; Chen, X.; Wang, N. Abscisic acid and regulation of the sugar transporter gene MdSWEET9b promote apple sugar accumulation. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 2081–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellarin, S.D.; Gambetta, G.A.; Wada, H.; Krasnow, M.N.; Cramer, G.R.; Peterlunger, E.; Shackel, K.A.; Matthews, M.A. Characterization of major ripening events during softening in grape: Turgor, sugar accumulation, abscisic acid metabolism, colour development, and their relationship with growth. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, P.; Sadeghnezhad, E.; Wang, J.; Yu, W.; Zheng, J.; Zhong, R.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, T.; Fang, J.; et al. VvSnRK1-VvSS3 regulates sugar accumulation during grape berry ripening in response to abscisic acid. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 320, 112208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.M.; Xie, L.H.; Lin, Y.; Zhong, B.L.; Wan, S.B. Transcriptome and weighted gene co-expression network analyses reveal key genes and pathways involved in early fruit ripening in Citrus sinensis. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; He, W.; Wang, K.; Ran, Y.; Li, W.; Wu, T.; Wang, P.; Cui, G.; Huang, B. Phytohormone cross-talk during fruit ripening: Linked biosynthesis and signaling. Plant Horm. 2025, 1, e010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Mei, L.; Wu, M.; Wei, W.; Shan, W.; Gong, Z.; Yang, F.; Yan, F.; Zhang, Q.; Luo, Y.; et al. SlARF10, an auxin response factor, is involved in chlorophyll and sugar accumulation during tomato fruit development. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 5507–5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alferez, F.; de Carvalho, D.U.; Boakye, D. Interplay between abscisic acid and gibberellins, as related to ethylene and sugars, in regulating maturation of non-climacteric fruit. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.-F.; Chai, Y.-M.; Li, C.-L.; Lu, D.; Luo, J.-J.; Qin, L.; Shen, Y.-Y. Abscisic acid plays an important role in the regulation of strawberry fruit ripening. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumos, J. Gene regulation in climacteric fruit ripening. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 102042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tijero, V.; Teribia, N.; Munoz, P.; Munne-Bosch, S. Implication of Abscisic acid on ripening and quality in sweet cherries: Differential effects during pre- and post-harvest. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.Y.; Neuhaus, H.E.; Cheng, J.T.; Bie, Z.L. Contributions of sugar transporters to crop yield and fruit quality. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2275–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.; Tavares, R.M.; Gerós, H. Utilization and transport of glucose in Olea europaea cell suspensions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 1510–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, C.; Grof, C.P.L. Sucrose transporters of higher plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2010, 13, 287e298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, J.-S.; Chen, L.-Q.; Sosso, D.; Julius, B.T.; Lin, I.; Qu, X.-Q.; Braun, D.M.; Frommer, W.B. Sweets, transporters for intracellular and intercellular sugar translocation. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2015, 25, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Mao, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, S.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Sheng, X.; Zhai, X.; Liu, J.H.; Li, C. CBL1/CIPK23 phosphorylates tonoplast sugar transporter TST2 to enhance sugar accumulation in sweet orange (Citrus sinensis). J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2025, 67, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lyu, H.; Chen, J.; Cao, X.; Du, R.; Ma, L.; Wang, N.; Zhu, Z.; Rao, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Releasing a sugar brake generates sweeter tomato without yield penalty. Nature 2024, 635, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Yu, X.; Mao, Z.; Li, M.; Zhao, Z.; Cai, C.; Dahro, B.; Liu, J.; Li, C. CsbHLH122/CsMYBS3-CsSUT2 contributes to the rapid accumulation of sugar in the ripening stage of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis). Plant J. 2025, 122, e70156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Delrot, S.; Fan, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, D.; Dong, F.; García-Caparros, P.; Li, S.; Dai, Z.; Liang, Z. The transcription factors ERF105 and NAC72 regulate expression of a sugar transporter gene and hexose accumulation in grape. Plant Cell 2024, 37, koae326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, W.; Nambeesan, S.U.; Li, Q.; Qiao, X.; Yang, B.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S. PbrbZIP15 promotes sugar accumulation in pear via activating the transcription of the glucose isomerase gene PbrXylA1. Plant J. 2024, 117, 1392–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zheng, J.; Wan, Q.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Q.; Wan, S.; Chen, J. Identification of key pathways and candidate genes controlling organ size through transcriptome and weighted gene Co-expression network analyses in navel orange plants (Citrus sinensis). Genes 2025, 16, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Fan, Y.; Xu, M.; Huang, Z.; Wang, D.; Sun, C.; Li, S. CitSAR-mediated coordination of sucrose and citrate metabolism in citrus fruits. Plant Physiol. 2025, 198, kiaf228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Fan, J.; Bi, X.; Tu, X.; Li, X.; Cao, M.; Liu, Z.; Lin, A.; Wang, C.; Xu, P.; et al. A NAC transcription factor and a MADS-box protein antagonistically regulate sucrose accumulation in strawberry receptacles. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiaf043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.X.; Gao, J.H.; Shen, Y.Y. Abscisic acid controls sugar accumulation essential to strawberry fruit ripening via the FaRIPK1-FaTCP7FaSTP13/FaSPT module. Plant J. 2024, 119, 1400–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.H.; Chen, S.H.; Wu, H.H.; Ho, C.W.; Ko, M.T.; Lin, C.Y. CytoHubba: Identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst. Biol. 2014, 8, S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, W.; Liu, Y.D.; Cao, Y.P.; Zhang, R.X.; Han, Y.P. A subgroup I bZIP transcription factor PpbZIP18 plays an important role in sucrose accumulation in peach. Mol. Hortic. 2025, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Li, W.; Chen, H.; Shi, J.; Zhu, H.; Chen, W.; Lu, W.; Li, X.; Zhu, X. E3 ligase SINAT5 mediates ERF113 stability and negatively governs the module of ABI5-like-ERF113 in regulating banana fruit ripening. New Phytol. 2025, 248, 70493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Wan, M.; Jia, B.; Ye, Z.; Liu, L.; Tang, X.; et al. MYB1R1 and MYC2 regulate ω-3 fatty acid desaturase involved in ABA-mediated suberization in the russet skin of a mutant of ‘Dangshansuli’ (Pyrus bretschneideri rehd.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 910938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zheng, L.; Ma, X.; Yu, T.; Gao, X.; Hou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cao, X.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; et al. An ABF5b-HsfA2h/HsfC2a-NCED2b/POD4/HSP26 module integrates multiple signaling pathway to modulate heat stress tolerance in wheat. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 4735–4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.Q.; Jiang, Y.; Li, J.G.; Lin, F.; Holm, M.; Deng, X.W. BBX21, an Arabidopsis B-box protein, directly activates HY5 and is targeted by COP1 for 26S proteasome mediated degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 7655–7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.Q. COP1 and BBXs-HY5-mediated light signal transduction in plants. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 1748–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Ye, W.; Jiang, Q.; Lin, H.; Hu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Bian, Y.; Zhao, F.; Dong, J.; Xu, D. BBX9 forms feedback loops with PIFs and BBX21 to promote photomorphogenic development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1934–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-H.; Liu, J.-J.; Chen, K.-L.; Li, H.-W.; He, J.; Guan, B.; He, L. Comparative transcriptome and proteome profiling of two Citrus sinensis cultivars during fruit development and ripening. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Shi, Y.; Liu, S.; Jin, R.; Sun, J.; Grierson, D.; Li, S.; Chen, K. The transcription factor CitZAT5 modifies sugar accumulation and hexose proportion in citrus fruit. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 1858–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.J.; Xu, X.; Gong, Z.H.; Tang, Y.W.; Wu, M.B.; Yan, F.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, F.Q.; Hu, X.W.; et al. Auxin response factor 6A regulates photosynthesis, sugar accumulation, and fruit development in tomato. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, J.H.; Topping, J.F.; Liu, J.; Lindsey, K. Abscisic acid regulates root growth under osmotic stress conditions via an interacting hormonal network with cytokinin, ethylene and auxin. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Qiao, J.; Li, Y.; Quan, R.; Huang, R. Abscisic acid promotes auxin biosynthesis to inhibit primary root elongation in rice. Plant Physiol. 2023, 191, 1953–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.H.; Ni, Y.; Chen, C.J.; Xiong, W.D.; Gan, Q.Q.; Jia, X.F.; Jin, S.R.; Yang, J.F.; Guo, Y.J. Unlocking the synergy: ABA seed priming enhances drought tolerance in seedlings of sweet sorghum through ABA-IAA crosstalk. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 5952–5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Annotation | GS | MM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cs_ont_2g004470 | NAC domain-containing protein 73; NAC73 | 0.895 | −0.908 |

| Cs_ont_7g025420 | MYB1R1 | 0.840 | −0.877 |

| Cs_ont_2g025530 | ERF113 | −0.810 | 0.882 |

| Cs_ont_2g014800 | Heat stress transcription factor A-4; Hsf A-4 | −0.884 | 0.907 |

| Cs_ont_9g006370 | Heat stress transcription factor A-6b; Hsf A-6b | −0.818 | 0.925 |

| Cs_ont_5g050360 | MYC2 | −0.916 | 0.929 |

| Cs_ont_3g002820 | B-box zinc finger protein 21; BBX21 | −0.923 | 0.937 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Xu, C.; Chen, Z.; Pei, Q.; Huang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Wan, S. Identification of Novel Regulators of Fruit Sugar Accumulation Based on Transcriptome and WGCNA in Citrus sinensis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412161

Chen J, Xu C, Chen Z, Pei Q, Huang Z, Chen Q, Wan S. Identification of Novel Regulators of Fruit Sugar Accumulation Based on Transcriptome and WGCNA in Citrus sinensis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412161

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jianmei, Chunli Xu, Zhenmin Chen, Qingyu Pei, Zixin Huang, Qiong Chen, and Shubei Wan. 2025. "Identification of Novel Regulators of Fruit Sugar Accumulation Based on Transcriptome and WGCNA in Citrus sinensis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412161

APA StyleChen, J., Xu, C., Chen, Z., Pei, Q., Huang, Z., Chen, Q., & Wan, S. (2025). Identification of Novel Regulators of Fruit Sugar Accumulation Based on Transcriptome and WGCNA in Citrus sinensis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412161