Significance of EVs in Prostate Cancer Bone Metastases

Abstract

1. Introduction

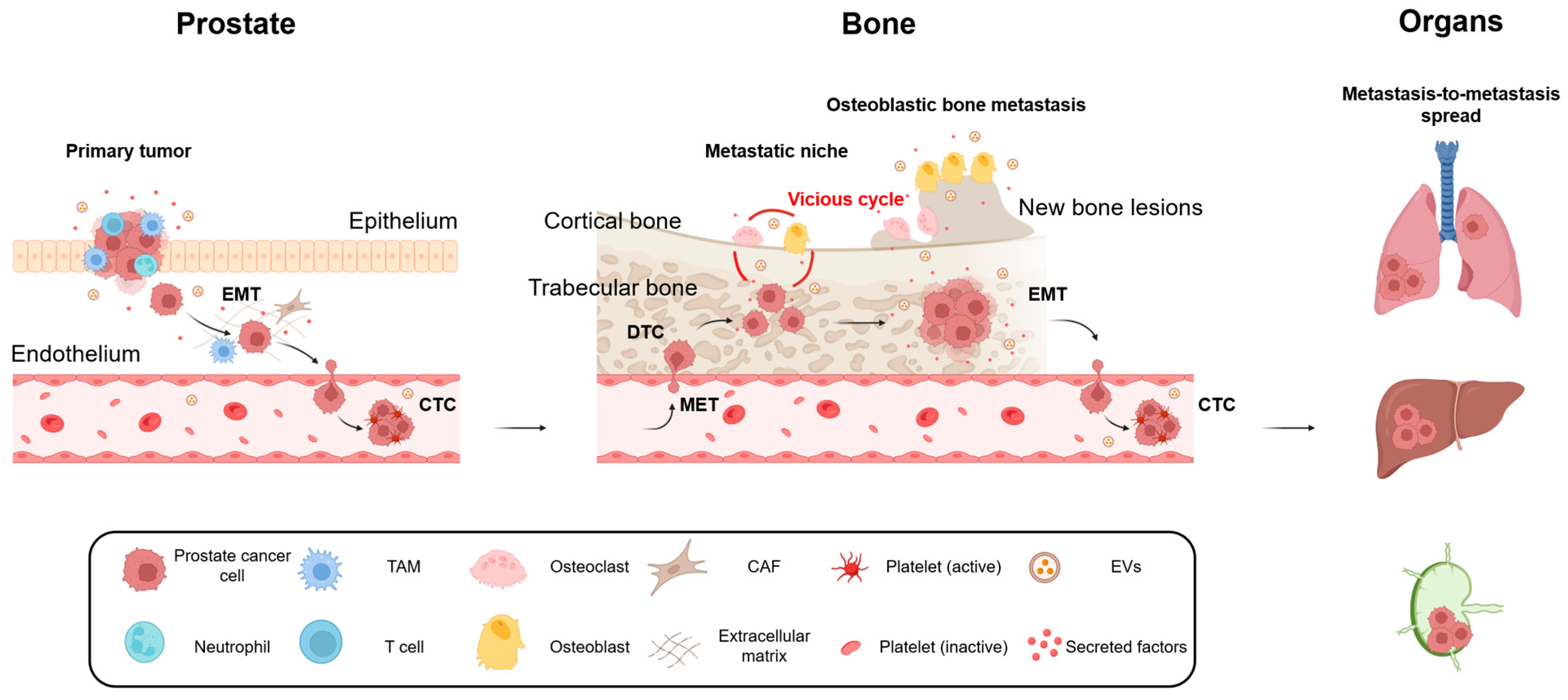

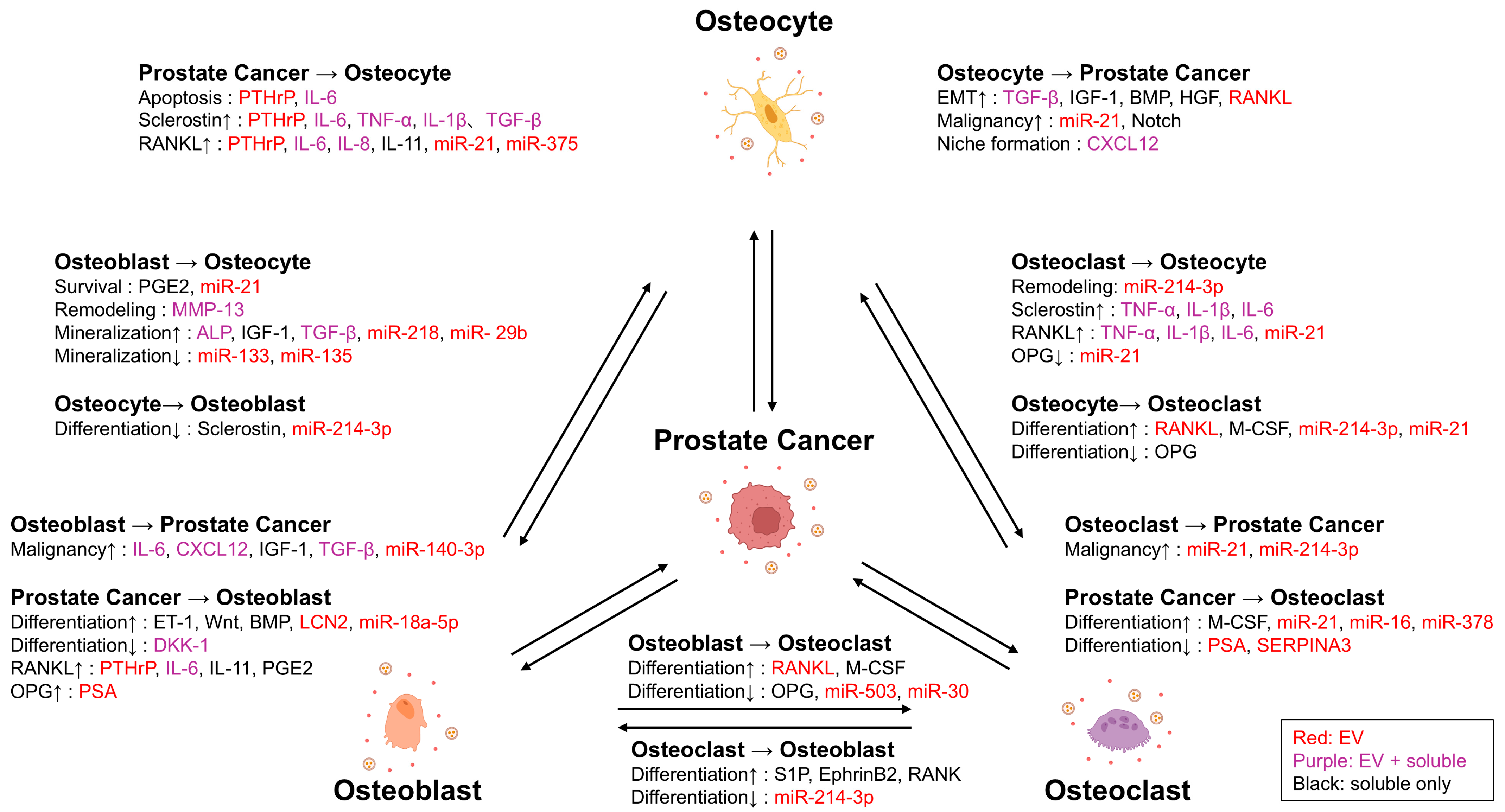

2. Molecular and Cellular Insights into Prostate Cancer Bone Metastasis

3. The Role of Osteoclast in Bone Metastasis

4. The Role of Osteoblast in Bone Metastasis

5. The Direction of EV Research for Developing Novel Therapeutic Approach Toward Bone Metastasis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, C.; Stahl, P. Transferrin recycling in reticulocytes: pH and iron are important determinants of ligand binding and processing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1983, 113, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, R.M.; Adam, M.; Hammond, J.R.; Orr, L.; Turbide, C. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes). J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 9412–9420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, B.T.; Teng, K.; Wu, C.; Adam, M.; Johnstone, R.M. Electron microscopic evidence for externalization of the transferrin receptor in vesicular form in sheep reticulocytes. J. Cell Biol. 1985, 101, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, G.; Nijman, H.W.; Stoorvogel, W.; Liejendekker, R.; Harding, C.V.; Melief, C.J.; Geuze, H.J. B lymphocytes secrete antigen-presenting vesicles. J. Exp. Med. 1996, 183, 1161–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lötvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegtel, D.M.; Cosmopoulos, K.; Thorley-Lawson, D.A.; van Eijndhoven, M.A.; Hopmans, E.S.; Lindenberg, J.L.; de Gruijl, T.D.; Würdinger, T.; Middeldorp, J.M. Functional delivery of viral miRNAs via exosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6328–6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, J.C.; Gonda, D.; Kim, R.; Carter, B.S.; Chen, C.C. Biogenesis of extracellular vesicles (EV): Exosomes, microvesicles, retrovirus-like vesicles, and apoptotic bodies. J. Neuro-Oncol. 2013, 113, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R. The biology and function of exosomes in cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoshino, A.; Costa-Silva, B.; Shen, T.L.; Rodrigues, G.; Hashimoto, A.; Tesic Mark, M.; Molina, H.; Kohsaka, S.; Di Giannatale, A.; Ceder, S.; et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 2015, 527, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404, Erratum in J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12451. https://doi.org/10.1002/jev2.12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Luo, Y.; He, W.; Zhao, Y.; Kong, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhong, G.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, J.; et al. Exosomal long noncoding RNA LNMAT2 promotes lymphatic metastasis in bladder cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dejima, H.; Iinuma, H.; Kanaoka, R.; Matsutani, N.; Kawamura, M. Exosomal microRNA in plasma as a non-invasive biomarker for the recurrence of non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 13, 1256–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, P.S.; Parkin, R.K.; Kroh, E.M.; Fritz, B.R.; Wyman, S.K.; Pogosova-Agadjanyan, E.L.; Peterson, A.; Noteboom, J.; O’Briant, K.C.; Allen, A.; et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 10513–10518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, T.; Sugimachi, K.; Iinuma, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Kurashige, J.; Sawada, G.; Ueda, M.; Uchi, R.; Ueo, H.; Takano, Y.; et al. Exosomal microRNA in serum is a novel biomarker of recurrence in human colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 113, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Müller, V.; Milde-Langosch, K.; Trillsch, F.; Pantel, K.; Schwarzenbach, H. Diagnostic and prognostic relevance of circulating exosomal miR-373, miR-200a, miR-200b and miR-200c in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 16923–16935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.S.; Ho, J.Y.; Chiang, J.H.; Yu, C.P.; Yu, D.S. Exosome-Derived LINC00960 and LINC02470 Promote the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Aggressiveness of Bladder Cancer Cells. Cells 2020, 9, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zheng, H.; Luo, Y.; Kong, Y.; An, M.; Li, Y.; He, W.; Gao, B.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, H.; et al. SUMOylation promotes extracellular vesicle-mediated transmission of lncRNA ELNAT1 and lymph node metastasis in bladder cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e146431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liang, C.; Chen, X. Exosomal LINC00355 derived from cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes bladder cancer cell resistance to cisplatin by regulating miR-34b-5p/ABCB1 axis. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2021, 53, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 17–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgstrand, J.T.; Røder, M.A.; Klemann, N.; Toft, B.G.; Lichtensztajn, D.Y.; Brooks, J.D.; Brasso, K.; Vainer, B.; Iversen, P. Trends in incidence and 5-year mortality in men with newly diagnosed, metastatic prostate cancer-A population-based analysis of 2 national cohorts. Cancer 2018, 124, 2931–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, C.J.; Chen, Y.H.; Carducci, M.; Liu, G.; Jarrard, D.F.; Eisenberger, M.; Wong, Y.N.; Hahn, N.; Kohli, M.; Cooney, M.M.; et al. Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannock, I.F.; de Wit, R.; Berry, W.R.; Horti, J.; Pluzanska, A.; Chi, K.N.; Oudard, S.; Théodore, C.; James, N.D.; Turesson, I.; et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1502–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menges, D.; Yebyo, H.G.; Sivec-Muniz, S.; Haile, S.R.; Barbier, M.C.; Tomonaga, Y.; Schwenkglenks, M.; Puhan, M.A. Treatments for Metastatic Hormone-sensitive Prostate Cancer: Systematic Review, Network Meta-analysis, and Benefit-harm assessment. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2022, 5, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bono, J.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, R.E. Metastatic bone disease: Clinical features, pathophysiology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2001, 27, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probert, C.; Dottorini, T.; Speakman, A.; Hunt, S.; Nafee, T.; Fazeli, A.; Wood, S.; Brown, J.E.; James, V. Communication of prostate cancer cells with bone cells via extracellular vesicle RNA; a potential mechanism of metastasis. Oncogene 2019, 38, 1751–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logothetis, C.J.; Lin, S.H. Osteoblasts in prostate cancer metastasis to bone. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2005, 5, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, M.Y.; Rathkopf, D.E.; Kantoff, P. Treatment of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Annu. Rev. Med. 2019, 70, 479–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.E. Clinical features of metastatic bone disease and risk of skeletal morbidity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 6243s–6249s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.D.; Nogueira, L.; Devasia, T.; Mariotto, A.B.; Yabroff, K.R.; Jemal, A.; Kramer, J.; Siegel, R.L. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 409–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaggi, G.; Scagliotti, G.V. Management of bone metastases in cancer: A review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2005, 56, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronquist, G.; Brody, I. The prostasome: Its secretion and function in man. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1985, 822, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zijlstra, C.; Stoorvogel, W. Prostasomes as a source of diagnostic biomarkers for prostate cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weilbaecher, K.N.; Guise, T.A.; McCauley, L.K. Cancer to bone: A fatal attraction. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazaki, J.; Higa, T.; Akimoto, S.; Masai, M.; Isaka, S. Clinical course of bone metastasis from prostatic cancer following endocrine therapy: Examination with bone x-ray. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1992, 324, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roudier, M.P.; Morrissey, C.; True, L.D.; Higano, C.S.; Vessella, R.L.; Ott, S.M. Histopathological assessment of prostate cancer bone osteoblastic metastases. J. Urol. 2008, 180, 1154–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonou, H.; Ochiai, A.; Goya, M.; Kanomata, N.; Hokama, S.; Morozumi, M.; Sugaya, K.; Hatano, T.; Ogawa, Y. Intraosseous growth of human prostate cancer in implanted adult human bone: Relationship of prostate cancer cells to osteoclasts in osteoblastic metastatic lesions. Prostate 2004, 58, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubendorf, L.; Schöpfer, A.; Wagner, U.; Sauter, G.; Moch, H.; Willi, N.; Gasser, T.C.; Mihatsch, M.J. Metastatic patterns of prostate cancer: An autopsy study of 1589 patients. Hum. Pathol. 2000, 31, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guise, T.A.; Mundy, G.R. Cancer and bone. Endocr. Rev. 1998, 19, 18–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundy, G.R. Metastasis to bone: Causes, consequences and therapeutic opportunities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2002, 2, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewing, J. Neoplastic Diseases; WB Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, O.V. The function of the vertebral veins and their role in the spread of metastases. Ann. Surg. 1940, 112, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paget, S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. Lancet 1889, 133, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, G.D. Mechanisms of bone metastasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.X.; Bos, P.D.; Massagué, J. Metastasis: From dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, J.P.; Acloque, H.; Huang, R.Y.; Nieto, M.A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell 2009, 139, 871–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alix-Panabières, C.; Riethdorf, S.; Pantel, K. Circulating Tumor Cells and Bone Marrow Micrometastasis. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 5013–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, B.Z.; Pollard, J.W. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell 2010, 141, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.M.; Gaur, A.B.; Lengyel, E.; Peter, M.E. The miR-200 family determines the epithelial phenotype of cancer cells by targeting the E-cadherin repressors ZEB1 and ZEB2. Genes. Dev. 2008, 22, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, P.A.; Bert, A.G.; Paterson, E.L.; Barry, S.C.; Tsykin, A.; Farshid, G.; Vadas, M.A.; Khew-Goodall, Y.; Goodall, G.J. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosaka, N.; Iguchi, H.; Hagiwara, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Takeshita, F.; Ochiya, T. Neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2)-dependent exosomal transfer of angiogenic microRNAs regulate cancer cell metastasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 10849–10859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.X.; Schneider, A.; Jung, Y.; Wang, J.; Dai, J.; Wang, J.; Cook, K.; Osman, N.I.; Koh-Paige, A.J.; Shim, H.; et al. Skeletal localization and neutralization of the SDF-1(CXCL12)/CXCR4 axis blocks prostate cancer metastasis and growth in bone. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiozawa, Y.; Pedersen, E.A.; Havens, A.M.; Jung, Y.; Mishra, A.; Joseph, J.; Kim, J.K.; Patel, L.R.; Ying, C.; Ziegler, A.M.; et al. Human prostate cancer metastases target the hematopoietic stem cell niche to establish footholds in mouse bone marrow. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 1298–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, P. Bone and the hematopoietic niche: A tale of two stem cells. Blood 2011, 117, 5281–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymaekers, K.; Stegen, S.; Van Gastel, N.; Carmeliet, G. The vasculature: A vessel for bone metastasis. Bonekey Rep. 2015, 4, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.N.; Riba, R.D.; Zacharoulis, S.; Bramley, A.H.; Vincent, L.; Costa, C.; MacDonald, D.D.; Jin, D.K.; Shido, K.; Kerns, S.A.; et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature 2005, 438, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guise, T.A.; Yin, J.J.; Taylor, S.D.; Kumagai, Y.; Dallas, M.; Boyce, B.F.; Yoneda, T.; Mundy, G.R. Evidence for a causal role of parathyroid hormone-related protein in the pathogenesis of human breast cancer-mediated osteolysis. J. Clin. Investig. 1996, 98, 1544–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guise, T.A. Breaking down bone: New insight into sites of bone metastasis and how to prevent them. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.J.; Pollock, C.B.; Kelly, K. Mechanisms of cancer metastasis to the bone. Cell Res. 2005, 15, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, E.T.; Brown, J. Prostate cancer bone metastases promote both osteolytic and osteoblastic activity. J. Cell Biochem. 2004, 91, 718–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guise, T.A. The vicious cycle of bone metastases. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2002, 2, 570–572. [Google Scholar]

- Urabe, F.; Kosaka, N.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ito, K.; Otsuka, K.; Soekmadji, C.; Egawa, S.; Kimura, T.; Ochiya, T. Metastatic prostate cancer-derived extracellular vesicles facilitate osteoclastogenesis by transferring the CDCP1 protein. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2023, 12, 12312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Dai, L.; Li, J.; Dong, C. Lung adenocarcinoma cell-derived exosomal miR-21 facilitates osteoclastogenesis. Gene 2018, 666, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagiya, T.; Nakamura, S. Expression profiling of microRNAs in RAW264.7 cells treated with a combination of tumor necrosis factor alpha and RANKL during osteoclast differentiation. J. Periodontal Res. 2013, 48, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, M.; Battafarano, G.; D’Agostini, M.; Del Fattore, A. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Bone Metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.B.; Chan-Tack, K.; Hedican, S.P.; Magnuson, S.R.; Opgenorth, T.J.; Steven Bova, G.; Simons, J.W. Endothelin-1 Production and Decreased Endothelin B Receptor Expression in Advanced Prostate Cancer1. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.J.; Mohammad, K.S.; Käkönen, S.M.; Harris, S.; Wu-Wong, J.R.; Wessale, J.L.; Padley, R.J.; Garrett, I.R.; Chirgwin, J.M.; Guise, T.A. A causal role for endothelin-1 in the pathogenesis of osteoblastic bone metastases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 10954–10959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.L.; Keller, E.T. The role of Wnts in bone metastases. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006, 25, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Keller, J.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; Yao, Z.; Keller, E.T. Bone morphogenetic protein-6 promotes osteoblastic prostate cancer bone metastases through a dual mechanism. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 8274–8285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonou, H.; Horiguchi, Y.; Ohno, Y.; Namiki, K.; Yoshioka, K.; Ohori, M.; Hatano, T.; Tachibana, M. Prostate-specific antigen stimulates osteoprotegerin production and inhibits receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand expression by human osteoblasts. Prostate 2007, 67, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borel, M.; Lollo, G.; Magne, D.; Buchet, R.; Brizuela, L.; Mebarek, S. Prostate cancer-derived exosomes promote osteoblast differentiation and activity through phospholipase D2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.; Zhao, C.; Wang, R.; Ren, L.; Qiu, H.; Zou, Z.; Ding, H.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Dong, S. Antagonizing exosomal miR-18a-5p derived from prostate cancer cells ameliorates metastasis-induced osteoblastic lesions by targeting Hist1h2bc and activating Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Genes Dis. 2023, 10, 1626–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Li, Z.; Wang, D.; Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Cao, J.; Wang, Z. Role of exosomes in prostate cancer bone metastasis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2023, 748, 109784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Yuan, H.; Xu, H.; Fong, C.; Wang, X.; Proia, D.; Snyder, L.A.; Damek-Poprawa, M.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Prostate cancer cell-stromal cell cross-talk via FGFR1 mediates prostate cancer progression in bone. Oncogene 2013, 32, 2874–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancotti, F.G. Mechanisms governing metastatic dormancy and reactivation. Cell 2013, 155, 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Hayashi, Y.; Sato, S.; Nakayama, J.; Urabe, F.; Shimasaki, T.; Nakamura, E.; Matui, Y.; Fujimoto, H.; et al. Osteoblast-derived extracellular vesicles exert osteoblastic and tumor-suppressive functions via SERPINA3 and LCN2 in prostate cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2023, 17, 2147–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiya, N.; Suzuki, H.; Yano, M.; Endo, T.; Takano, M.; Komaru, A.; Kawamura, K.; Sekita, N.; Imamoto, T.; Ichikawa, T. Implications of serum bone turnover markers in prostate cancer patients with bone metastasis. Urology 2010, 75, 1446–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, J.X.; Shao, Z.Q. miR-21 targets and inhibits tumor suppressor gene PTEN to promote prostate cancer cell proliferation and invasion: An experimental study. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2017, 10, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagle, P.; Smith, N.; Adekoya, T.O.; Li, Y.; Kim, S.; Rios-Colon, L.; Deep, G.; Niture, S.; Albanese, C.; Suy, S.; et al. Knockdown of microRNA-214-3p Promotes Tumor Growth and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.; Takahashi, N.; Jimi, E.; Udagawa, N.; Takami, M.; Kotake, S.; Nakagawa, N.; Kinosaki, M.; Yamaguchi, K.; Shima, N.; et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates osteoclast differentiation by a mechanism independent of the ODF/RANKL-RANK interaction. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 191, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C.A.; Nakashima, T.; Takayanagi, H. Osteocyte control of osteoclastogenesis. Bone 2013, 54, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, J.; Guo, B.; Liang, C.; Dang, L.; Lu, C.; He, X.; Cheung, H.Y.; Xu, L.; Lu, C.; et al. Osteoclast-derived exosomal miR-214-3p inhibits osteoblastic bone formation. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.-H.; Sui, B.-D.; Du, F.-Y.; Shuai, Y.; Zheng, C.-X.; Zhao, P.; Yu, X.-R.; Jin, Y. miR-21 deficiency inhibits osteoclast function and prevents bone loss in mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guise, T.A. Parathyroid hormone-related protein and bone metastases. Cancer 1997, 80, 1572–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Siegel, P.M.; Shu, W.; Drobnjak, M.; Kakonen, S.M.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; Guise, T.A.; Massague, J. A multigenic program mediating breast cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer Cell 2003, 3, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Zhao, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Nie, G.; Peng, J.; Wang, A.; Zhang, P.; Tian, W.; Li, Q.; et al. Osteoclast-derived microRNA-containing exosomes selectively inhibit osteoblast activity. Cell Discov. 2016, 2, 16015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Guo, B.; Li, Q.; Peng, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, A.; Li, D.; Hou, Z.; Lv, K.; Kan, G.; et al. miR-214 targets ATF4 to inhibit bone formation. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Sun, W.; Zhang, P.; Ling, S.; Li, Y.; Zhao, D.; Peng, J.; Wang, A.; Li, Q.; Song, J.; et al. miR-214 promotes osteoclastogenesis by targeting Pten/PI3k/Akt pathway. RNA Biol. 2015, 12, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikebuchi, Y.; Aoki, S.; Honma, M.; Hayashi, M.; Sugamori, Y.; Khan, M.; Kariya, Y.; Kato, G.; Tabata, Y.; Penninger, J.M.; et al. Coupling of bone resorption and formation by RANKL reverse signalling. Nature 2018, 561, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Kogure, A.; Yoshioka, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sakamoto, S.; Ichikawa, T.; Ochiya, T. Extracellular Vesicles From Prostate Cancer-Corrupted Osteoclasts Drive a Chain Reaction of Inflammatory Osteolysis and Tumour Progression at the Bone Metastatic Site. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2025, 14, e70091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Liang, M.; Wu, Y.; Luo, F.; Ma, Z.; Dong, S.; Xu, J.; Dou, C. Osteoclast-derived apoptotic bodies couple bone resorption and formation in bone remodeling. Bone Res. 2021, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, S.S.; Li, X.; Miranti, C.K. The host microenvironment influences prostate cancer invasion, systemic spread, bone colonization, and osteoblastic metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.; Kneissel, M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: From human mutations to treatments. Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Guo, K.; Ma, S.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Yan, R.; Huang, Y.; Li, T.; He, S.; et al. Osteoblast-derived exosomal miR-140-3p targets ACER2 and increases the progression of prostate cancer via the AKT/mTOR pathway-mediated inhibition of autophagy. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e70206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonet, W.S.; Lacey, D.L.; Dunstan, C.R.; Kelley, M.; Chang, M.S.; Lüthy, R.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Wooden, S.; Bennett, L.; Boone, T.; et al. Osteoprotegerin: A novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Nature 1997, 389, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappariello, A.; Loftus, A.; Muraca, M.; Maurizi, A.; Rucci, N.; Teti, A. Osteoblast-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Are Biological Tools for the Delivery of Active Molecules to Bone. J. Bone Miner. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Miner. Res. 2018, 33, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, H.C. Vesicles associated with calcification in the matrix of epiphyseal cartilage. J. Cell Biol. 1969, 41, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, E.E. Biomineralization and matrix vesicles in biology and pathology. Semin. Immunopathol. 2011, 33, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vietri, M.; Radulovic, M.; Stenmark, H. The many functions of ESCRTs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Siljander, P.R.; Andreu, Z.; Zavec, A.B.; Borràs, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Carvalho, J.; et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocucci, E.; Meldolesi, J. Ectosomes and exosomes: Shedding the confusion between extracellular vesicles. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Osaki, F.; Hiragi, S.; Sakamaki, Y.; Fukuda, M. ALIX and ceramide differentially control polarized small extracellular vesicle release from epithelial cells. EMBO Rep. 2021, 22, e51475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkovic, K.; Hsu, C.; Chiantia, S.; Rajendran, L.; Wenzel, D.; Wieland, F.; Schwille, P.; Brügger, B.; Simons, M. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science 2008, 319, 1244–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urabe, F.; Kosaka, N.; Sawa, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ito, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Kimura, T.; Egawa, S.; Ochiya, T. miR-26a regulates extracellular vesicle secretion from prostate cancer cells via targeting SHC4, PFDN4, and CHORDC1. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, T.; Nakayama, J.; Urabe, F.; Ito, K.; Nishida-Aoki, N.; Kitagawa, M.; Yokoi, A.; Kuroda, M.; Hattori, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; et al. Aberrant regulation of serine metabolism drives extracellular vesicle release and cancer progression. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marleau, A.M.; Chen, C.-S.; Joyce, J.A.; Tullis, R.H. Exosome removal as a therapeutic adjuvant in cancer. J. Transl. Med. 2012, 10, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciravolo, V.; Huber, V.; Ghedini, G.C.; Venturelli, E.; Bianchi, F.; Campiglio, M.; Morelli, D.; Villa, A.; Della Mina, P.; Menard, S.; et al. Potential role of HER2-overexpressing exosomes in countering trastuzumab-based therapy. J. Cell. Physiol. 2012, 227, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida-Aoki, N.; Tominaga, N.; Takeshita, F.; Sonoda, H.; Yoshioka, Y.; Ochiya, T. Disruption of Circulating Extracellular Vesicles as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy against Cancer Metastasis. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2017, 25, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severic, M.; Ma, G.; Pereira, S.G.T.; Ruiz, A.; Cheung, C.C.L.; Al-Jamal, W.T. Genetically-engineered anti-PSMA exosome mimetics targeting advanced prostate cancer in vitro and in vivo. J. Control. Release Off. J. Control. Release Soc. 2021, 330, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, J.R.; Kim, Y.; Horjeti, E.; Arafa, A.; Gunn, H.; De Bruycker, A.; Phillips, R.; Song, D.; Childs, D.S.; Sartor, O.A.; et al. PSMA+ Extracellular Vesicles Are a Biomarker for SABR in Oligorecurrent Prostate Cancer: Analysis from the STOMP-like and ORIOLE Trial Cohorts. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 31, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Xi, W.; Ni, J.; Jiang, J.; Lei, Y.; Li, L.; Chu, J.; Li, R.; An, Y.; Ouyang, Y.; et al. Genetically modified extracellular vesicles loaded with activated gasdermin D potentially inhibit prostate-specific membrane antigen-positive prostate carcinoma growth and enhance immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2025, 315, 122894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vader, P.; Mol, E.A.; Pasterkamp, G.; Schiffelers, R.M. Extracellular vesicles for drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 106, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Li, S.; Song, J.; Ji, T.; Zhu, M.; Anderson, G.J.; Wei, J.; Nie, G. A doxorubicin delivery platform using engineered natural membrane vesicle exosomes for targeted tumor therapy. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 2383–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ito, K.; Tamura, T.; Urabe, F.; Sakamoto, S.; Kimura, T.; Egawa, S.; Ochiya, T. Significance of EVs in Prostate Cancer Bone Metastases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412160

Ito K, Tamura T, Urabe F, Sakamoto S, Kimura T, Egawa S, Ochiya T. Significance of EVs in Prostate Cancer Bone Metastases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412160

Chicago/Turabian StyleIto, Kagenori, Takaaki Tamura, Fumihiko Urabe, Shinichi Sakamoto, Takahiro Kimura, Shin Egawa, and Takahiro Ochiya. 2025. "Significance of EVs in Prostate Cancer Bone Metastases" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412160

APA StyleIto, K., Tamura, T., Urabe, F., Sakamoto, S., Kimura, T., Egawa, S., & Ochiya, T. (2025). Significance of EVs in Prostate Cancer Bone Metastases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12160. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412160