Investigation of the Binding of the Macrolide Antibiotic Telithromycin to Human Serum Albumin by NMR Spectroscopy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

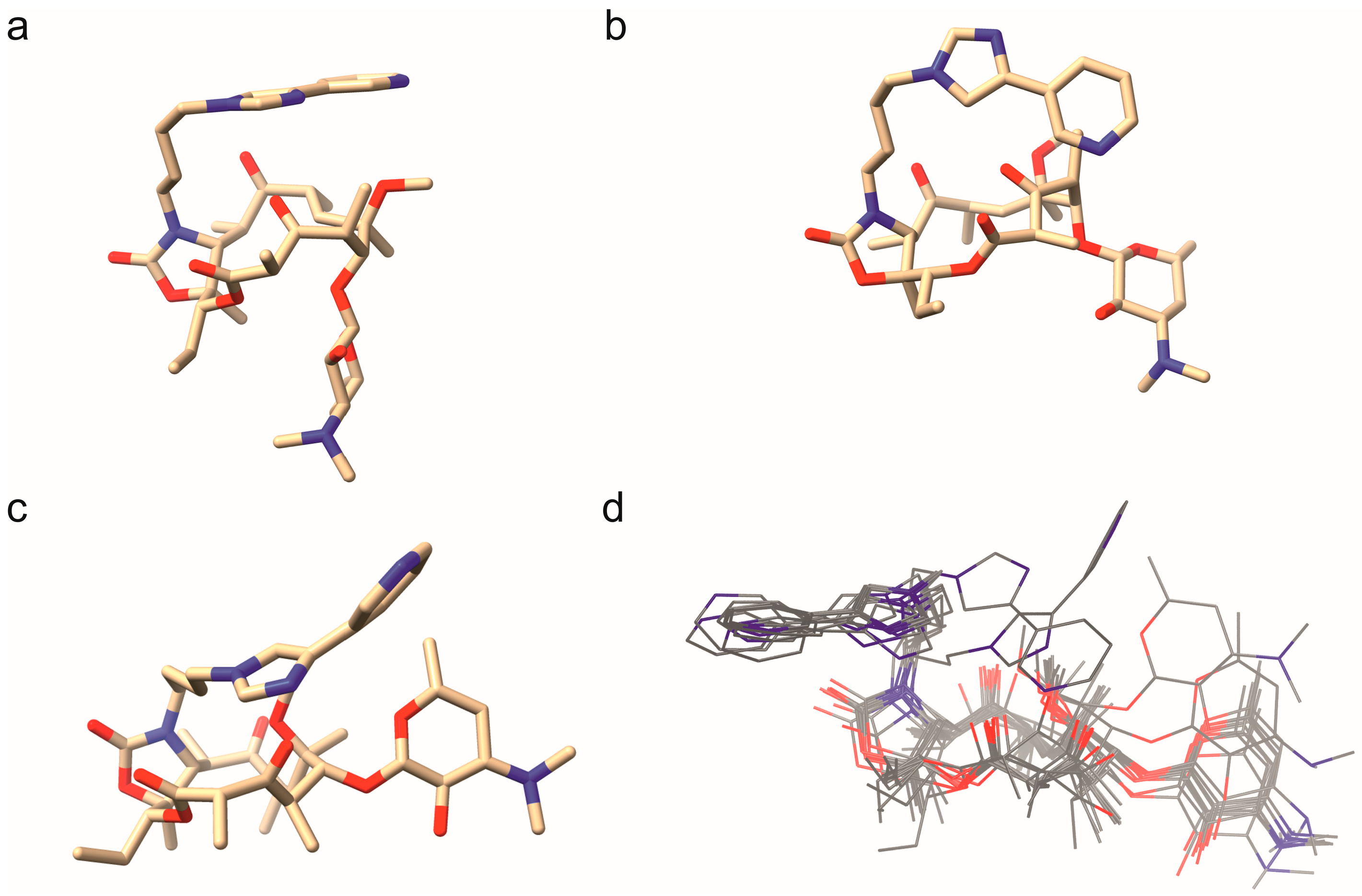

Telithromycin Adopts a Closed Conformation in the Presence of HSA

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. NMR Methods

3.2. Computational Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HSA | Human serum albumin |

| TM | Telithromycin |

| DOSY | Diffusion ordered spectroscopy |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| FA | Fatty acid |

| PDB | Protein data bank |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| RMSD | Root mean square deviation |

| DFA | Density functional approximation |

| (tr)NOE | (transferred) nuclear Overhauser effect |

References

- Kwiatkowska, B.; Maślińska, M. Macrolide Therapy in Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2012, 2012, 636157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfister, P.; Jenni, S.; Poehlsgaard, J.; Thomas, A.; Douthwaite, S.; Ban, N.; Böttger, E.C. The Structural Basis of Macrolide–Ribosome Binding Assessed Using Mutagenesis of 23S rRNA Positions 2058 and 2059. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 342, 1569–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivapalasingam, S.; Steigbigel, N.H. Macrolides, Clindamycin, and Ketolides. In Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 358–376.e6. ISBN 978-1-4557-4801-3. [Google Scholar]

- Whitman, M.S.; Tunkel, A.R. Azithromycin and Clarithromycin: Overview and Comparison with Erythromycin. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 1992, 13, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechère, J.-C. Macrolide Resistance Mechanisms in Gram-Positive Cocci. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2001, 18, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryskier, A. New Research in Macrolides and Ketolides since 1997. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 1999, 8, 1171–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barman Balfour, J.A.; Figgitt, D.P. Telithromycin. Drugs 2001, 61, 815–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryskier, A. Ketolides. In Antimicrobial Agents; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 527–569. ISBN 978-1-68367-191-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, J.M. Macrolides and Ketolides: Azithromycin, Clarithromycin, Telithromycin. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 18, 621–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namour, F.; Wessels, D.H.; Pascual, M.H.; Reynolds, D.; Sultan, E.; Lenfant, B. Pharmacokinetics of the New Ketolide Telithromycin (HMR 3647) Administered in Ascending Single and Multiple Doses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlund, C.; Alván, G.; Barkholt, L.; Vacheron, F.; Nord, C.E. Pharmacokinetics and Comparative Effects of Telithromycin (HMR 3647) and Clarithromycin on the Oropharyngeal and Intestinal Microflora. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000, 46, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berisio, R.; Harms, J.; Schluenzen, F.; Zarivach, R.; Hansen, H.A.S.; Fucini, P.; Yonath, A. Structural Insight into the Antibiotic Action of Telithromycin against Resistant Mutants. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 4276–4279, Erratum in J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, K.D.; Hanson, J.S.; Pope, S.D.; Rissmiller, R.W.; Purdum, P.P.; Banks, P.M. Brief Communication: Severe Hepatotoxicity of Telithromycin: Three Case Reports and Literature Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 144, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrot, X.; Bernard, N.; Vial, C.; Antoine, J.C.; Laurent, H.; Vial, T.; Confavreux, C.; Vukusic, S. Myasthenia Gravis Exacerbation or Unmasking Associated with Telithromycin Treatment. Neurology 2006, 67, 2256–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Pea, F.; Lipman, J. The Clinical Relevance of Plasma Protein Binding Changes. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2013, 52, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedermann, C.J. Hypoalbuminemia as Surrogate and Culprit of Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiga, R.P.; Paiva, J.-A. Pharmacokinetics–Pharmacodynamics Issues Relevant for the Clinical Use of Beta-Lactam Antibiotics in Critically Ill Patients. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Yin, Z. Characterization of Plasma Protein Binding Dissociation with Online SPE-HPLC. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, M.; Curry, S.; Terreno, E.; Galliano, M.; Fanali, G.; Narciso, P.; Notari, S.; Ascenzi, P. The Extraordinary Ligand Binding Properties of Human Serum Albumin. IUBMB Life Int. Union. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Life 2005, 57, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Gilmartin, K.; Octaviano, S.; Villar, F.; Remache, B.; Regan, J. Using Human Serum Albumin Binding Affinities as a Proactive Strategy to Affect the Pharmacodynamics and Pharmacokinetics of Preclinical Drug Candidates. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2022, 5, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.A.; Waters, N.J. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Considerations for Drugs Binding to Alpha-1-Acid Glycoprotein. Pharm. Res. 2019, 36, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, K.D.; Klosterman, K.E.; Mukundan, H.; Kubicek-Sutherland, J.Z. Macrolides: From Toxins to Therapeutics. Toxins 2021, 13, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattringer, R.; Urbauer, E.; Traunmüller, F.; Zeitlinger, M.; Dehghanyar, P.; Zeleny, P.; Graninger, W.; Müller, M.; Joukhadar, C. Pharmacokinetics of Telithromycin in Plasma and Soft Tissues after Single-Dose Administration to Healthy Volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 4650–4653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Chapel, S.; Montay, G.; Hardy, P.; Barrett, J.S.; Sica, D.; Swan, S.K.; Noveck, R.; Leroy, B.; Bhargava, V.O. Effect of Ketoconazole on the Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Telithromycin and Clarithromycin in Older Subjects with Renal Impairment. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 43, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckerman, J.M.; Qamar, F.; Bono, B.R. Review of Macrolides (Azithromycin, Clarithromycin), Ketolids (Telithromycin) and Glycylcyclines (Tigecycline). Med. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 95, 761–791, viii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskew, M.W.; Koslen, M.M.; Benight, A.S. Ligand Binding to Natural and Modified Human Serum Albumin. Anal. Biochem. 2021, 612, 113843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, G.; Di Masi, A.; Ascenzi, P. Serum Albumin: A Multifaced Enzyme. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudlow, G.; Birkett, D.J.; Wade, D.N. Spectroscopic Techniques in the Study of Protein Binding. A Fluorescence Technique for the Evaluation of the Albumin Binding and Displacement of Warfarin and Warfarin-Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1975, 2, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.X.; Recum, H.A. Affinity-Based Drug Delivery. Macromol. Biosci. 2011, 11, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyab, S.; Feroz, S.R. Serum Albumin: Clinical Significance of Drug Binding and Development as Drug Delivery Vehicle. In Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 123, pp. 193–218. ISBN 978-0-12-822087-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gossert, A.D.; Jahnke, W. NMR in Drug Discovery: A Practical Guide to Identification and Validation of Ligands Interacting with Biological Macromolecules. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2016, 97, 82–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosol, S.; Schrank, E.; Krajačić, M.B.; Wagner, G.E.; Meyer, N.H.; Göbl, C.; Rechberger, G.N.; Zangger, K.; Novak, P. Probing the Interactions of Macrolide Antibiotics with Membrane-Mimetics by NMR Spectroscopy. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 5632–5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danelius, E.; Poongavanam, V.; Peintner, S.; Wieske, L.H.E.; Erdélyi, M.; Kihlberg, J. Solution Conformations Explain the Chameleonic Behaviour of Macrocyclic Drugs. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 5231–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, P.; Tepeš, P.; Lazić, V. Epitope Mapping of Macrolide Antibiotics to Bovine Serum Albumin by Saturation Transfer Difference NMR Spectroscopy. Croat. Chem. Acta 2007, 80, 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, M.P. The Transferred NOE. In Modern Magnetic Resonance; Webb, G.A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-3-319-28275-6. [Google Scholar]

- Anglister, J.; Srivastava, G.; Naider, F. Detection of Intermolecular NOE Interactions in Large Protein Complexes. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2016, 97, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clore, G.M.; Gronenborn, A.M. Theory and Applications of the Transferred Nuclear Overhauser Effect to the Study of the Conformations of Small Ligands Bound to Proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 1982, 48, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyal, Z.; Matzov, D.; Krupkin, M.; Wekselman, I.; Paukner, S.; Zimmerman, E.; Rozenberg, H.; Bashan, A.; Yonath, A. Structural Insights into Species-Specific Features of the Ribosome from the Pathogen Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E5805–E5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxmi Pradhan, B.; Lodhi, L.; Kishor Dey, K.; Ghosh, M. Analyzing Atomic Scale Structural Details and Nuclear Spin Dynamics of Four Macrolide Antibiotics: Erythromycin, Clarithromycin, Azithromycin, and Roxithromycin. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 17733–17770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, P.; Barber, J.; Čikoš, A.; Arsic, B.; Plavec, J.; Lazarevski, G.; Tepeš, P.; Košutić-Hulita, N. Free and Bound State Structures of 6-O-Methyl Homoerythromycins and Epitope Mapping of Their Interactions with Ribosomes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 5857–5867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanzer, S.; Pulido, S.A.; Tutz, S.; Wagner, G.E.; Kriechbaum, M.; Gubensäk, N.; Trifunovic, J.; Dorn, M.; Fabian, W.M.F.; Novak, P.; et al. Structural and Functional Implications of the Interaction between Macrolide Antibiotics and Bile Acids. Chem. Weinh. Bergstr. Ger. 2015, 21, 4350–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyperchem Professional, version 8.0.8; Hypercube Inc.: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2007.

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced Basis Sets of Split Valence, Triple Zeta Valence and Quadruple Zeta Valence Quality for H to Rn: Design and Assessment of Accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimme, S.; Antony, J.; Ehrlich, S.; Krieg, H. A Consistent and Accurate Ab Initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S.; Ehrlich, S.; Goerigk, L. Effect of the Damping Function in Dispersion Corrected Density Functional Theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-Functional Exchange-Energy Approximation with Correct Asymptotic Behavior. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional Thermochemistry. III. The Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Yang, W.; Parr, R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti Correlation-Energy Formula into a Functional of the Electron Density. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COSMOconf, version 4.3; COSMOlogic GmbH & Co. KG: Leverkusen, Germany, 2018.

- Vainio, M.J.; Johnson, M.S. Generating Conformer Ensembles Using a Multiobjective Genetic Algorithm. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 47, 2462–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868, Erratum in Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 1396–1396. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klamt, A.; Schüürmann, G. COSMO: A New Approach to Dielectric Screening in Solvents with Explicit Expressions for the Screening Energy and Its Gradient. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1993, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Karlsruhe and Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH. TURBOMOLE, version 7.9; University of Karlsruhe and Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2024.

- Von Arnim, M.; Ahlrichs, R. Performance of Parallel TURBOMOLE for Density Functional Calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 1746–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treutler, O.; Ahlrichs, R. Efficient Molecular Numerical Integration Schemes. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 102, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-Fitting Basis Sets for H to Rn. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2006, 8, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichkorn, K.; Treutler, O.; Öhm, H.; Häser, M.; Ahlrichs, R. Auxiliary Basis Sets to Approximate Coulomb Potentials. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995, 240, 283–290, Erratum in Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995, 242, 652–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2614(95)00838-U. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichkorn, K.; Weigend, F.; Treutler, O.; Ahlrichs, R. Auxiliary Basis Sets for Main Row Atoms and Transition Metals and Their Use to Approximate Coulomb Potentials. Theor. Chem. Acc. 1997, 97, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F. A Fully Direct RI-HF Algorithm: Implementation, Optimised Auxiliary Basis Sets, Demonstration of Accuracy and Efficiency. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2002, 4, 4285–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rotzinger, M.; Hartmann, P.; Muhry, B.; Stadler, K.; Boese, A.D.; Novak, P.; Zangger, K. Investigation of the Binding of the Macrolide Antibiotic Telithromycin to Human Serum Albumin by NMR Spectroscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12005. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412005

Rotzinger M, Hartmann P, Muhry B, Stadler K, Boese AD, Novak P, Zangger K. Investigation of the Binding of the Macrolide Antibiotic Telithromycin to Human Serum Albumin by NMR Spectroscopy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12005. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412005

Chicago/Turabian StyleRotzinger, Markus, Peter Hartmann, Barbara Muhry, Karina Stadler, A. Daniel Boese, Predrag Novak, and Klaus Zangger. 2025. "Investigation of the Binding of the Macrolide Antibiotic Telithromycin to Human Serum Albumin by NMR Spectroscopy" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12005. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412005

APA StyleRotzinger, M., Hartmann, P., Muhry, B., Stadler, K., Boese, A. D., Novak, P., & Zangger, K. (2025). Investigation of the Binding of the Macrolide Antibiotic Telithromycin to Human Serum Albumin by NMR Spectroscopy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12005. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412005