The Function and Role of Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 2 in Dental Pulp Cells and Tissue

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. ICAM2 Localization in Rat Dental Pulp Tissue and ICAM2 Expression in HDPCs

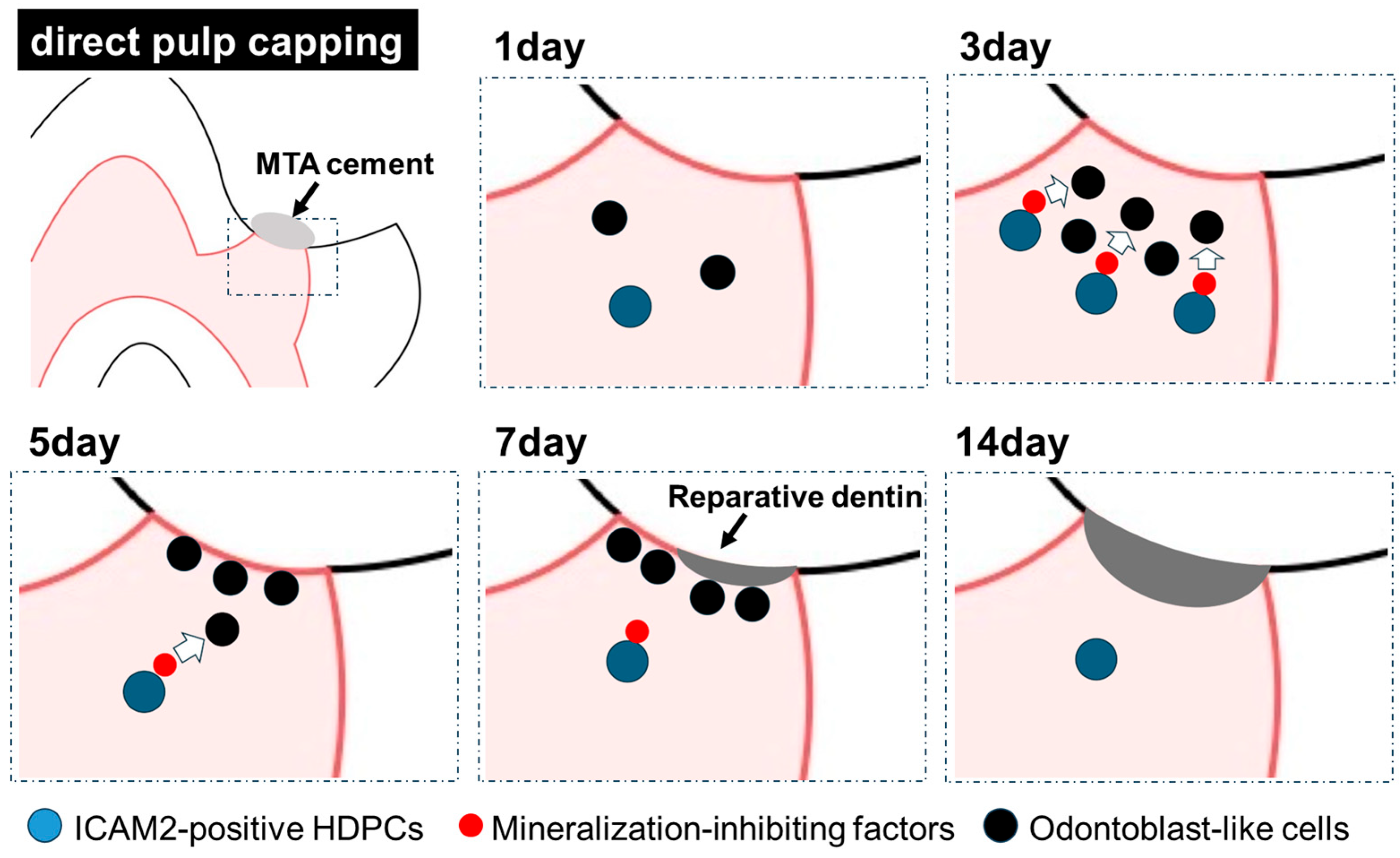

2.2. ICAM2 Expression in Rat Dental Pulp Tissue After Direct Pulp Capping

2.3. Effect of ICAM2 Knockdown on Odontoblast-like Differentiation of HDPCs

2.4. Role of ICAM2-Expressing HDPCs on Odontoblast-like Differentiation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

4.2. Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

4.3. Semi-Quantitative RT-PCR

4.4. Flow Cytometry

4.5. Rat Direct Pulp Capping Model

4.6. Histological Analysis

4.7. Immunofluorescent Staining

4.8. Odontoblast-like Differentiation Assay

4.9. Small Interfering RNA Transfection

4.10. Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS)

4.11. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.12. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MTA | mineral trioxide aggregate |

| ICAM2 | intercellular adhesion molecule 2 |

| HDPCs | human dental pulp cells |

| MACS | magnetic cell sorting |

| DSPP | dentin sialophosphoprotein |

| TH | tyrosine hydroxylase |

| OPN | osteopontin |

| βig-h3 | transforming growth factor-β-induced gene product-h3 |

| DMP1 | dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein 1 |

| RT-PCR | reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| α-MEM | alpha minimum essential medium |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| PFA | paraformaldehyde |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| EDTA | ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| H&A | hematoxylin and eosin |

| GAPDH | glyceraldehyde3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| RT | room temperature |

| siRNA | small interfering RNA |

| CM | control medium |

| DM | differentiation medium |

| ARS | alizarin red S |

References

- Goldberg, M.; Njeh, A.; Uzunoglu, E. Is Pulp Inflammation a Prerequisite for Pulp Healing and Regeneration? Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 347649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wang, C.; Ye, L. Healing Rate and Post-obturation Pain of Single- versus Multiple-visit Endodontic Treatment for Infected Root Canals: A Systematic Review. J. Endod. 2011, 37, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; Wu, Y.; Smales, R.J. Identifying and reducing risks for potential fractures inendodontically treated teeth. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Téclès, O.; Laurent, P.; Aubut, V.; About, I. Human tooth culture: A study model for reparative dentinogenesis and direct pulp capping materials biocompatibility. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2008, 85, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Ju, B.; Ni, R. Clinical outcome of direct pulp capping with MTA or calcium hydroxide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 17055–17060. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, T.J.; Ferracane, J.L.; Mancl, L. Northwest Practice-based Research Collaborative in Evidence-based Dentistry (NWP) Comparison of CaOH with MTA for direct pulp capping: A PBRN randomized clinical trial. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92, 16S–22S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsi, N.; Alamoudi, N.; Balto, K.; Al Mushayt, A. Clinical assessment of mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) as direct pulp capping in young permanent teeth. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2006, 31, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accorinte, M.L.; Loguercio, A.D.; Reis, A.; Carneiro, E.; Grande, R.H.; Murata, S.S.; Holland, R. Response of human dental pulp capped with MTA and calcium hydroxide pow-der. Oper. Dent. 2008, 33, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, T.R.; Torabinejad, M.; Abedi, H.R.; Bakland, L.K.; Kariyawasam, S.P. Using mineral trioxide aggregate as a pulp-capping material. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1996, 127, 1491–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraco, I.M., Jr.; Holland, R. Response of the pulp of dogs to capping with mineral trioxide aggregate or a calcium hydroxide cement. Dent. Traumatol. 2001, 174, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, R.; de Souza, V.; Nery, M.J.; Otoboni Filho, J.A.; Bernabé, P.F.; Dezan Júnior, E. Reaction of rat connective tissue to implanted dentin tubes filled with miner-al trioxide aggregate or calcium hydroxide. J. Endod. 1999, 253, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahmberg, C.G. Leukocyte adhesion: CD11/CD18 integrins and intercellular adhesion molecules. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1997, 9, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahmberg, C.G.; Tolvanen, M.; Kotovuori, P. Leukocyte adhesion--structure and function of human leukocyte beta2-integrins and their cellular ligands. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 245, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Bickford, J.K.; Luther, E.; Carpenito, C.; Takei, F.; Springer, T.A. Characterization of murine intercellular adhesion molecule-2. J. Immunol. 1996, 156, 4909–4914. [Google Scholar]

- Staunton, D.E.; Dustin, M.L.; Springer, T.A. Functional cloning of ICAM-2, a cell adhesion ligand for LFA-1 homologous to ICAM-1. Nature 1989, 339, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Fougerolles, A.R.; Stacker, S.A.; Schwarting, R.; Springer, T.A. Characterization of ICAM-2 and evidence for a third counter-receptor for LFA-1. J. Exp. Med. 1991, 174, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; Li, R.; Kotovuori, P.; Vermot-Desroches, C.; Wijdenes, J.; Arnaout, M.A.; Nortamo, P.; Gahmberget, C.G. Intercellular adhesion molecule-2 (CD102) binds to the leukocyte integrin CD11b/CD18 through the A domain. J. Immunol. 1995, 155, 3619–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.S.; Alon, R.; Klickstein, L.B. Sialylation of ICAM-2 on platelets impairs adhesion of leukocytes via LFA-1 and DC-SIGN. Inflammation 2004, 28, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Colmegna, I.; He, X.; Weyand, C.M.; Goronzy, J.J. Synoviocyte stimulation by the LFA-1-intercellular adhesion molecule-2-Ezrin-Akt pathway in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 1971–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Akiyama, M.; Nakahama, K.; Koshiishi, T.; Takeda, S.; Morita, I. Role of intercellular adhesion molecule-2 in osteoclastogenesis. Genes Cells 2012, 17, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Wada, N.; Hasegawa, D.; Miyaji, H.; Mitarai, H.; Tomokiyo, A.; Hamano, S.; Maeda, H. Semaphorin 3A induces odontoblastic phenotype in dental pulp stem cells. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 1282–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadowaki, M.; Yoshida, S.; Itoyama, T.; Tomokiyo, A.; Hamano, S.; Hasegawa, D.; Sugii, H.; Kaneko, H.; Sugiura, R.; Maeda, H. Involvement of M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization in Reparative Dentin Formation. Life 2022, 12, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serita, S.; Tomokiyo, A.; Hasegawa, D.; Hamano, S.; Sugii, H.; Yoshida, S.; Mizumachi, H.; Mitarai, H.; Monnouchi, S.; Wada, N.; et al. Transforming growth factor-β-induced gene product-h3 inhibits odontoblastic differentiation of dental pulp cells. Arch. Oral Biol. 2017, 78, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, D.; Wada, N.; Yoshida, S.; Mitarai, H.; Arima, M.; Tomokiyo, A.; Hamano, S.; Sugii, H.; Maeda, H. Wnt5a suppresses osteoblastic differentiation of human periodontal ligament stem cell-like cells via Ror2/JNK signaling. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 1752–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma-Martínez, E.; Mendoza-Núñez, V.M.; Santiago-Osorio, E. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from dental pulp: A review. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 4709572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.R.; Berdal, A.; Cooper, P.R.; Lumley, P.J.; Tomson, P.L.; Smith, A.J. Dentin-pulp complex regeneration: From lab to clinic. Adv. Dent. Res. 2011, 23, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronthos, S.; Mankani, M.; Brahim, J.; Robey, P.G.; Shi, S. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 13625–13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronthos, S.; Brahim, J.; Li, W.; Fisher, L.W.; Cherman, N.; Boyde, A.; DenBesten, P.; Gehron, R.P.; Shi, S. Stem cell properties of human dental pulp stem cells. J. Dent. Res. 2002, 81, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuratate, M.; Yoshiba, K.; Shigetani, Y.; Yoshiba, N.; Ohshima, H.; Okiji, T. Immunohistochemical analysis of nestin, osteopontin, and proliferating cells in the reparative process of exposed dental pulp capped with mineral trioxide aggregate. J. Endod. 2008, 34, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigetani, Y.; Yoshiba, K.; Kuratate, M.; Takei, E.; Yoshiba, N.; Yamanaka, Y.; Ohshima, H.; Okiji, T. Temporospatial localization of dentine matrix protein 1 following direct pulp capping with calcium hydroxide in rat molars. Int. Endod. J. 2015, 48, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujino, S.; Hamano, S.; Tomokiyo, A.; Sugiura, R.; Yamashita, D.; Hasegawa, D.; Sugii, H.; Fujii, S.; Itoyama, T.; Miyaji, H.; et al. Dopamine is involved in reparative dentin formation through odontoblastic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, J.; Montesin, F.E.; Brady, K.; Sweeney, R.; Curtis, R.V.; Ford, T.R. The constitution of mineral trioxide aggregate. Dent. Mater 2005, 21, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, K.; Tomokiyo, A.; Ono, T.; Ipposhi, K.; Alhasan, M.A.; Tsuchiya, A.; Hamano, S.; Sugii, H.; Yoshida, S.; Itoyama, T.; et al. Mineral trioxide aggregate immersed in sodium hypochlorite reduce the osteoblastic differentiation of human periodontal ligament stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Cao, L.; Fan, M.; Xu, Q. Direct Pulp Capping with Calcium Hydroxide or Mineral Trioxide Aggregate: A Meta-analysis. J. Endod. 2015, 41, 1412–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunert, M.; Lukomska-Szymanska, M. Bio-Inductive Materials in Direct and Indirect Pulp Capping—A Review Article. Materials 2020, 13, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chicarelli, L.P.G.; Webber, M.B.F.; Amorim, J.P.A.; Rangel, A.; Camilotti, V.; Sinhoreti, M.A.C.; Mendonça, M.J. Effect of Tricalcium Silicate on Direct Pulp Capping: Experimental Study in Rats. Eur. J. Dent. 2021, 15, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipposhi, K.; Tomokiyo, A.; Ono, T.; Yamashita, K.; Alhasan, M.A.; Hasegawa, D.; Hamano, S.; Yoshida, S.; Sugii, H.; Itoyama, T.; et al. Secreted Frizzled-Related Protein 1 Promotes Odontoblastic Differentiation and Reparative Dentin Formation in Dental Pulp Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombouts, C.; Jeanneau, C.; Bakopoulou, A.; About, I. Dental Pulp Stem Cell Recruitment Signals within Injured Dental Pulp Tissue. Dent. J. 2016, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couve, E.; Schmachtenberg, O. Schwann Cell Responses and Plasticity in Different Dental Pulp Scenarios. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eramo, S.; Natali, A.; Pinna, R.; Milia, E. Dental pulp regeneration via cell homing. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Udagawa, N.; Uehara, S.; Ishihara, A.; Mizoguchi, T.; Kikuchi, Y.; Takada, I.; Kato, S.; Kani, S.; et al. Wnt5a-Ror2 signaling between osteoblast-lineage cells and osteoclast precursors enhances osteoclastogenesis. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, A.; Iwata, T.; Yamato, M.; Okano, T.; Izumi, Y. Diverse functions of secreted frizzled-related proteins in the osteoblastogenesis of human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 3270–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, N.; Maeda, H.; Tanabe, K.; Tsuda, E.; Yano, K.; Nakamuta, H.; Akamine, A. Periodontal ligament cells secrete the factor that inhibits osteoclastic differentiation and function: The factor is osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor. J. Periodontal. Res. 2001, 36, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizumachi, H.; Yoshida, S.; Tomokiyo, A.; Hasegawa, D.; Hamano, S.; Yuda, A.; Sugii, H.; Serita, S.; Mitarai, H.; Koori, K.; et al. Calcium-sensing receptor-ERK signaling promotes odontoblastic differentiation of human dental pulp cells. Bone 2017, 101, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, N.; Maeda, H.; Hasegawa, D.; Gronthos, S.; Bartold, P.M.; Menicanin, D.; Fujii, S.; Yoshida, S.; Tomokiyo, A.; Monnouchi, S.; et al. Semaphorin3A induces mesenchymal-stem-like properties in human periodontal ligament cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2014, 23, 2225–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomczynslci, P.; Sacchi, N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol chloroform extraction. Anal. Biochem. 1987, 162, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Annealing Temperature | Semi-Quantitative RT-PCR | Size of Amplified Products | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | ||||

| (Abbreviation) | Primer Sequence Forward/Reverse | (°C) | Cycles | (bp) |

| ICAM1 | 5′-CTTGAGGGCACCTACCTCTG-3′/5′-TTCCGCTGGCGGTTATAGAG-3′ | 60 | 40 | 173 |

| ICAM2 | 5′-CCCTCTTCACCCTGATCTGC-3′/5′-TTCCACTGAGCCTGTTCGTC-3′ | 60 | 40 | 193 |

| ICAM3 | 5′-GGAGATCGTCTGCAACGTGA-3′/5′-CATGCAACTCACGGTCACTG-3′ | 60 | 40 | 142 |

| ICAM4 | 5′-CTCGGCACCCATTACACTGA-3′/5′-CATTTGCATAGGTACGCAGC-3′ | 60 | 40 | 120 |

| ICAM5 | 5′-CCCAGAGAGCTCCGAACCTT-3′/5′-TCGAGGGTGACATCAGGACT-3′ | 60 | 40 | 182 |

| DSPP | 5′-ATATTGAGGGCTGGAATGGGGA-3′/5′-TTTGTGGCTCCAGCATTGTCA-3′ | 60 | 40 | 136 |

| Nestin | 5′-TGGCCACGTACAGGACCCTCC-3′/5′-AGATCCAAGACGCCGGCCCT-3′ | 60 | 40 | 143 |

| TH | 5′-ATGCCGGTACTGGTTCTTCC-3′/5′-TGCCGAAAGGAAATGGGTCA-3′ | 60 | 40 | 90 |

| OPN | 5′-ACACATATGATGGCCGAGGTGA-3′/5′-TGTGAGGTGATGTCCTCGTCTGT-3′ | 60 | 40 | 115 |

| βig-h3 | 5′-TCCTGAAATACCACATTGGTGATGA-3′/5′-GACATGGACCACGCCATTTG-3′ | 60 | 40 | 160 |

| Wnt5a | 5′-CTGCAGCCAACTGGCAGGACT-3′/5′-CGCGGCTGCCTATCTGCATCA-3′ | 60 | 40 | 197 |

| β-actin | 5′-ATTGCCGACAGGATGCAGA-3′/5′-GAGTACTTGCGCTCAGGAGGA-3′ | 60 | 40 | 89 |

| Annealing Temperature | Semi-Quantitative RT-PCR | Size of Amplified Products | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | ||||

| (Abbreviation) | Primer Sequence Forward/Reverse | (°C) | Cycles | (bp) |

| ICAM2 | 5′-CCCTCTTCACCCTGATCTGC-3′/5′-TTCCACTGAGCCTGTTCGTC-3′ | 60 | 30 | 193 |

| GAPDH | 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCCAC-3′/5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′ | 60 | 20 | 452 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tashita, K.; Hasegawa, D.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Maeda, H. The Function and Role of Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 2 in Dental Pulp Cells and Tissue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412006

Tashita K, Hasegawa D, Huang Y, Zhao H, Maeda H. The Function and Role of Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 2 in Dental Pulp Cells and Tissue. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412006

Chicago/Turabian StyleTashita, Koudai, Daigaku Hasegawa, Yuxin Huang, He Zhao, and Hidefumi Maeda. 2025. "The Function and Role of Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 2 in Dental Pulp Cells and Tissue" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412006

APA StyleTashita, K., Hasegawa, D., Huang, Y., Zhao, H., & Maeda, H. (2025). The Function and Role of Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 2 in Dental Pulp Cells and Tissue. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412006