Functional Coupling of Calcium-Sensing Receptor and Polycystin-2 in Renal Epithelial Cells: Physiological Role and Potential Therapeutic Target in Polycystic Kidney Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

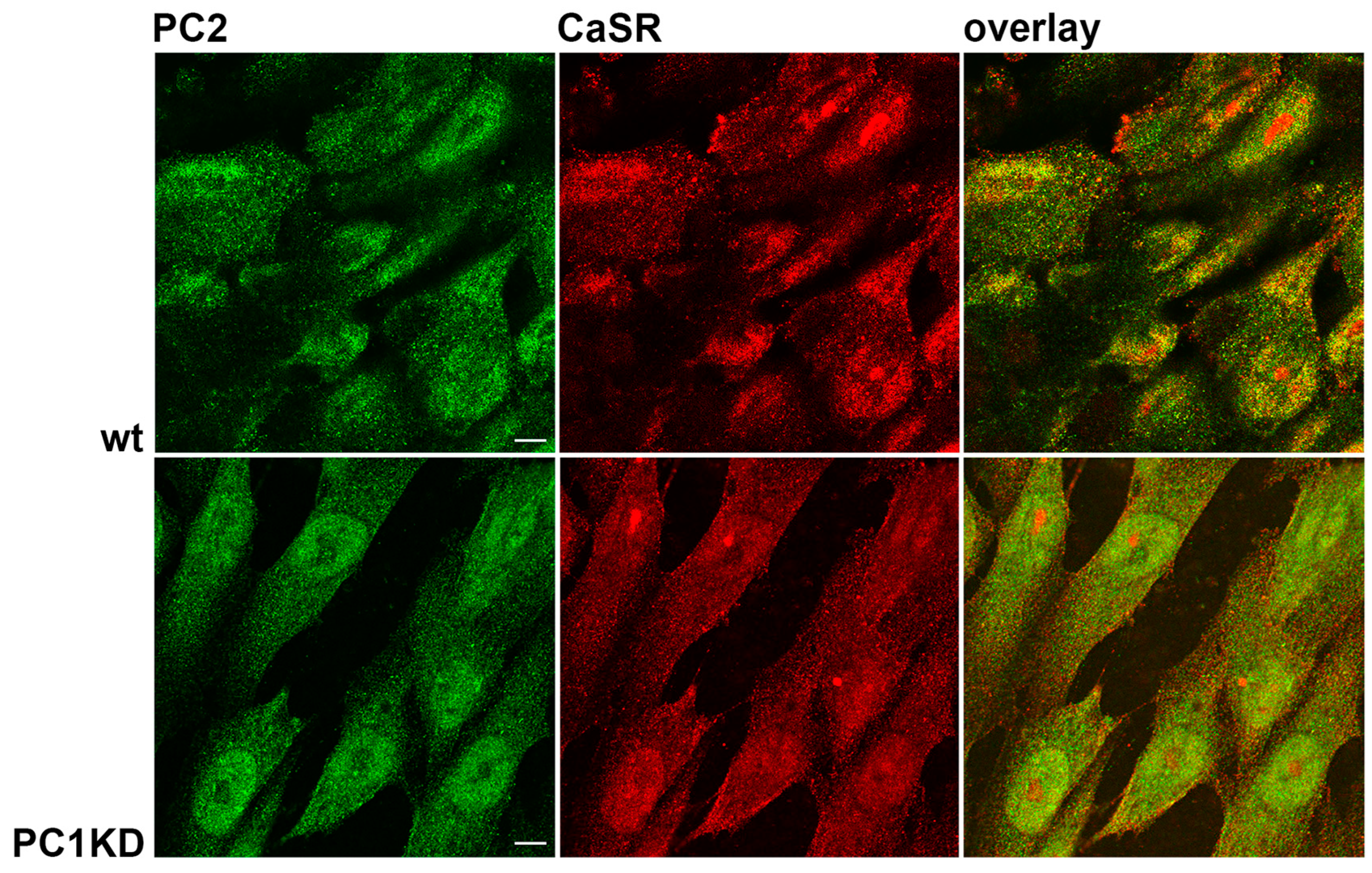

2.1. PC2 and CaSR Expression in PTEC

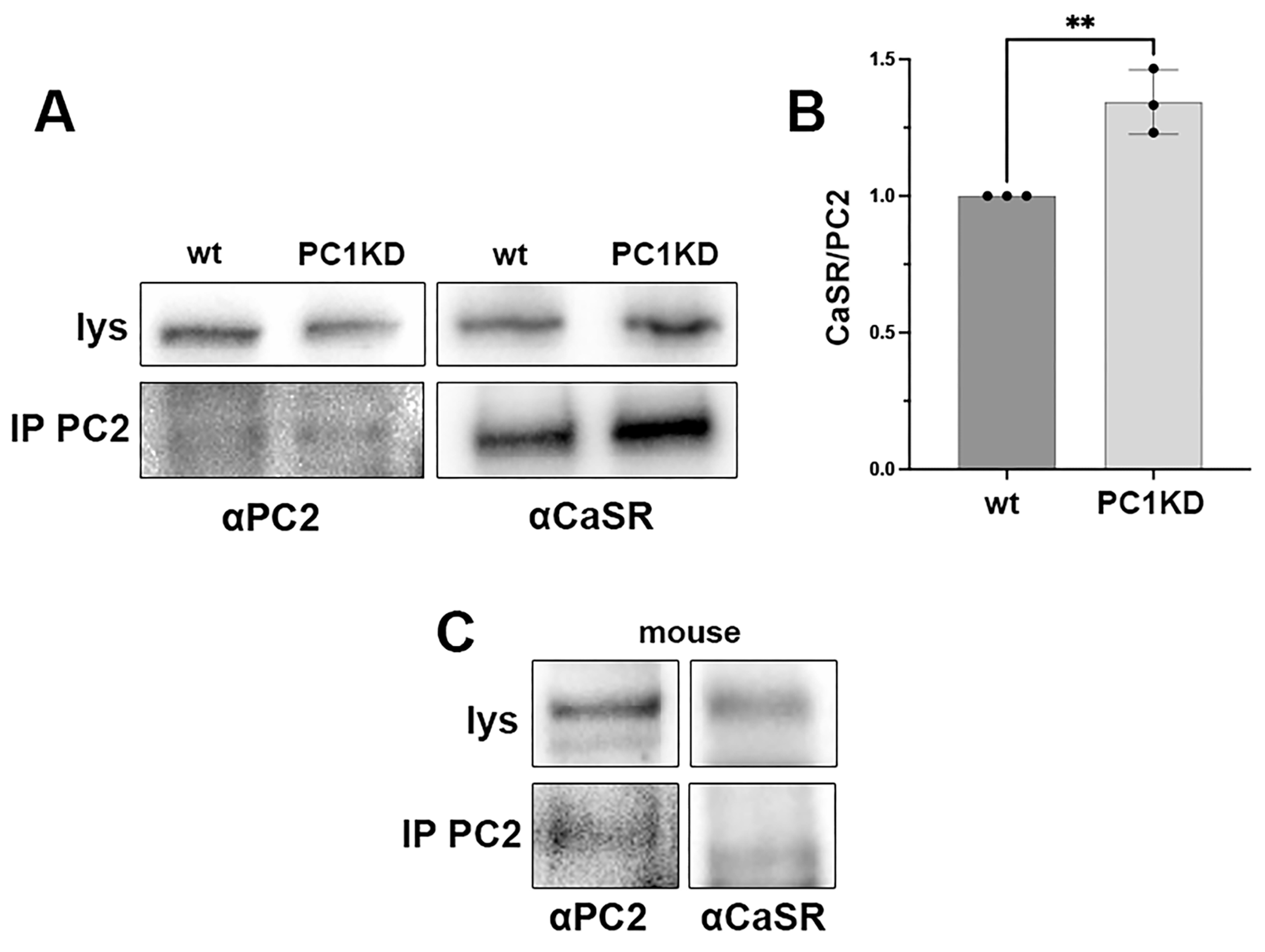

2.2. PC2 and CaSR Co-Immunoprecipitation in PTEC and Mouse

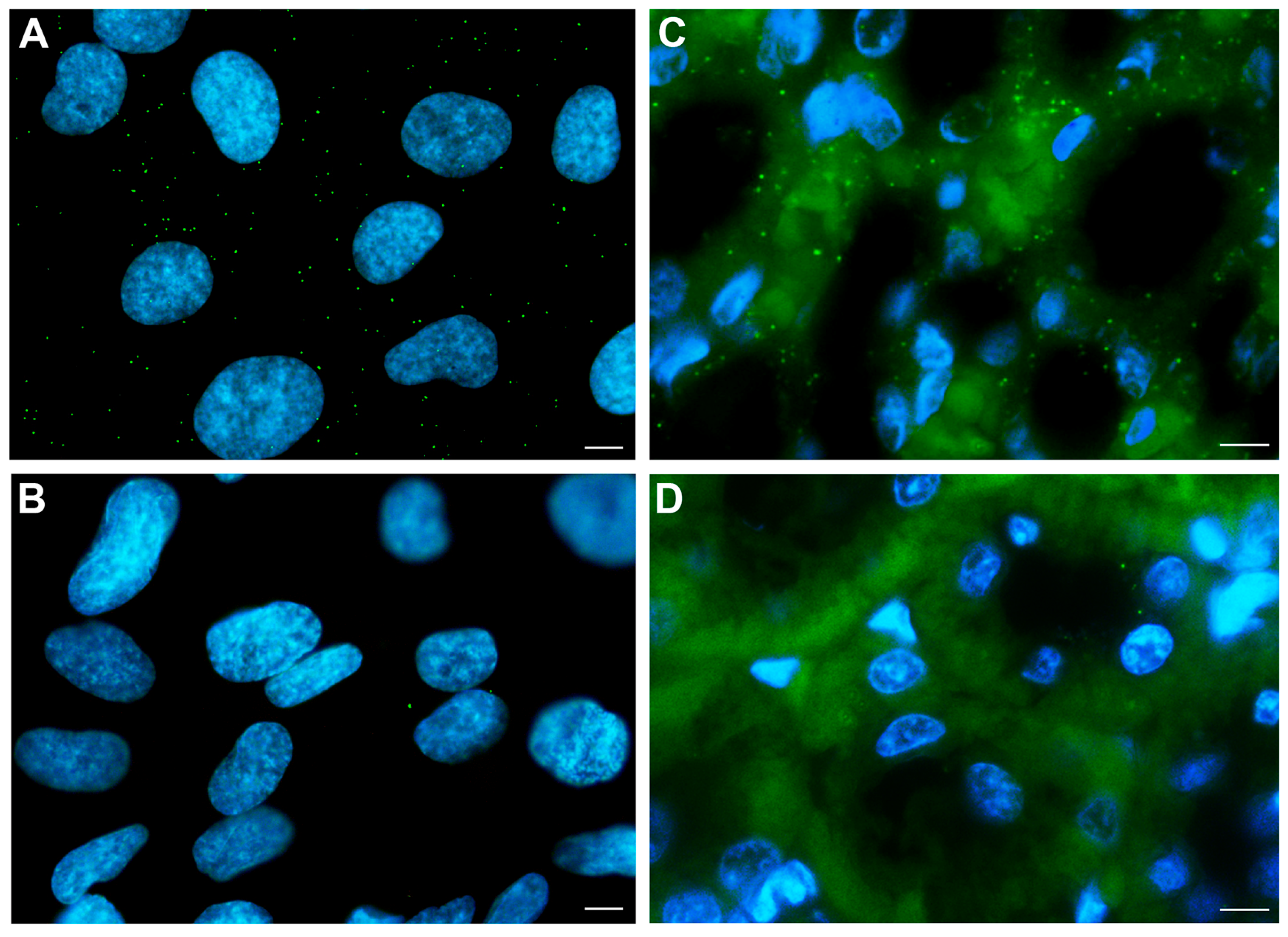

2.3. PC2 and CaSR Interaction

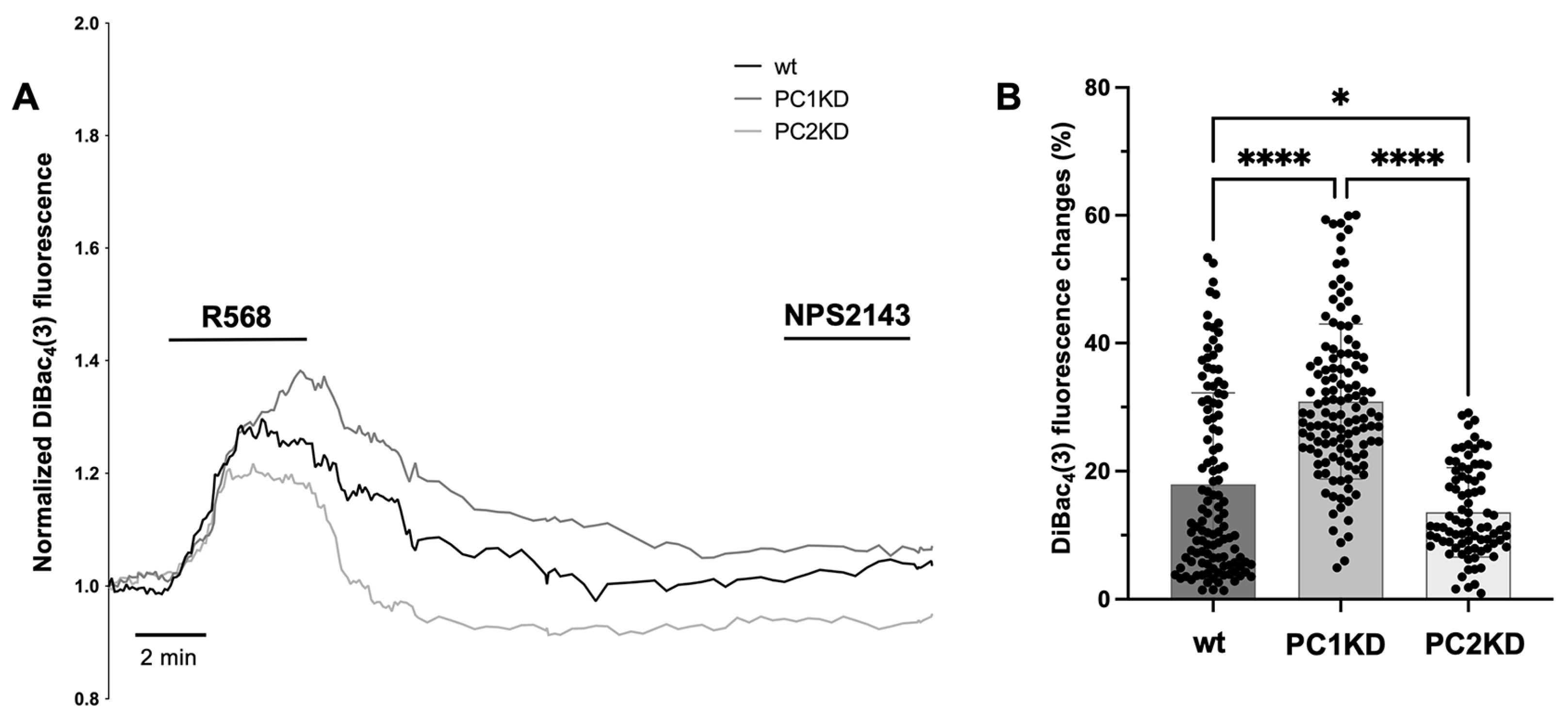

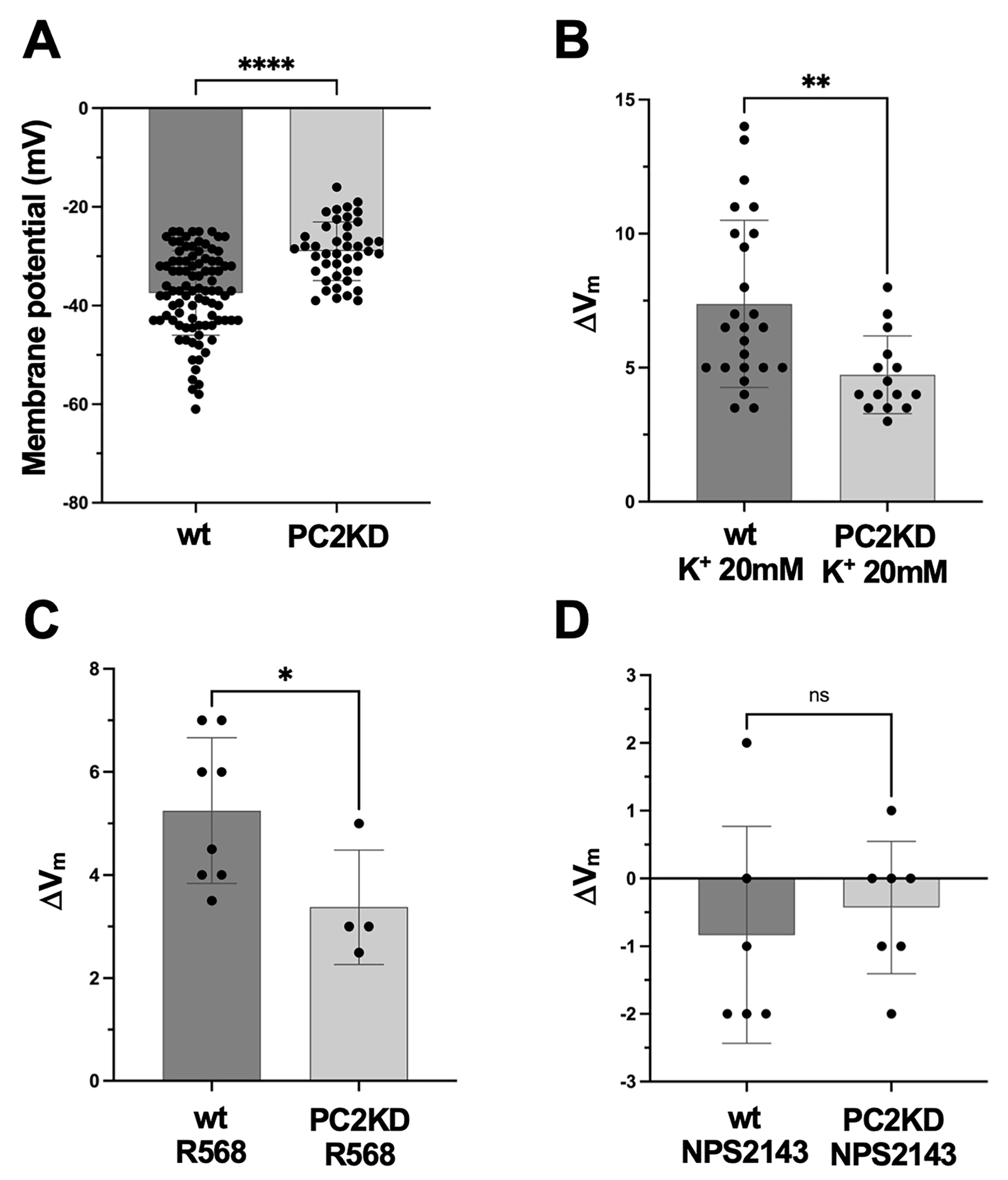

2.4. Membrane Potential Measurements

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Antibodies

4.3. Cell Culture

4.4. Immunofluorescence Microscopy

4.5. Immunoprecipitation

4.6. Gel Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting

4.7. Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA)

4.8. Fluorescence-Based Membrane Potential Measurements

4.9. Microelectrode Measurements of Plasma Membrane Potential

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clapham, D.E.; Julius, D.; Montell, C.; Schultz, G. International Union of Pharmacology. XLIX. Nomenclature and Structure-Function Relationships of Transient Receptor Potential Channels. Pharmacol. Rev. 2005, 57, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, A.L.; Ehrlich, B.E. Polycystin 2: A Calcium Channel, Channel Partner, and Regulator of Calcium Homeostasis in ADPKD. Cell. Signal. 2020, 66, 109490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, S.; Consugar, M.B.; Chapman, A.B.; Torres, V.E.; Guay-Woodford, L.M.; Grantham, J.J.; Bennett, W.M.; Meyers, C.M.; Walker, D.L.; Bae, K.; et al. Comprehensive Molecular Diagnostics in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 2143–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahboob, M.; Rout, P.; Leslie, S.W.; Bokhari, S.R.A. Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev, P.M.; Guo, L.; Chen, X.Z.; Segal, Y.; Peng, J.B.; Basora, N.; Babakhanlou, H.; Cruger, G.; Kanazirska, M.; Ye, C.-P.; et al. Polycystin-2 Is a Novel Cation Channel Implicated in Defective Intracellular Ca2+ Homeostasis in Polycystic Kidney Disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001, 282, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanaoka, K.; Qian, F.; Boletta, A.; Bhunia, A.K.; Piontek, K.; Tsiokas, L.; Sukhatme, V.P.; Guggino, W.B.; Germino, G.G. Co-Assembly of Polycystin-1 and -2 Produces Unique Cation-Permeable Currents. Nature 2000, 408, 990–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anyatonwu, G.I.; Ehrlich, B.E. Calcium Signaling and Polycystin-2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 322, 1364–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mangolini, A.; de Stephanis, L.; Aguiari, G. Role of Calcium in Polycystic Kidney Disease: From Signaling to Pathology. World J. Nephrol. 2016, 5, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Hu, F.; Ge, X.; Lei, J.; Yu, S.; Wang, T.; Zhou, Q.; Mei, C.; Shi, Y. Structure of the Human PKD1-PKD2 Complex. Science 2018, 361, eaat9819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauli, S.M.; Alenghat, F.J.; Luo, Y.; Williams, E.; Vassilev, P.; Li, X.; Elia, A.E.H.; Lu, W.; Brown, E.M.; Quinn, S.J.; et al. Polycystins 1 and 2 Mediate Mechanosensation in the Primary Cilium of Kidney Cells. Nat. Genet. 2003, 33, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif-Naeini, R.; Folgering, J.H.A.; Bichet, D.; Duprat, F.; Lauritzen, I.; Arhatte, M.; Jodar, M.; Dedman, A.; Chatelain, F.C.; Schulte, U.; et al. Polycystin-1 and -2 Dosage Regulates Pressure Sensing. Cell 2009, 139, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, P.; Nauli, S.M.; Li, X.; Coste, B.; Osorio, N.; Crest, M.; Brown, D.A.; Zhou, J. Gating of the Polycystin Ion Channel Signaling Complex in Neurons and Kidney Cells. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 740–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Vien, T.; Duan, J.; Sheu, S.-H.; DeCaen, P.G.; Clapham, D.E. Polycystin-2 Is an Essential Ion Channel Subunit in the Primary Cilium of the Renal Collecting Duct Epithelium. eLife 2018, 7, e33183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantero, M.D.R.; Cantiello, H.F. Polycystin-2 (TRPP2): Ion Channel Properties and Regulation. Gene 2022, 827, 146313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.Q.; Perez, P.L.; Soria, G.; Scarinci, N.; Smoler, M.; Morsucci, D.C.; Suzuki, K.; Cantero, M.D.R.; Cantiello, H.F. External Ca2+ Regulates Polycystin-2 (TRPP2) Cation Currents in LLC-PK1 Renal Epithelial Cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 350, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, D.; Valenti, G. Localization and Function of the Renal Calcium-Sensing Receptor. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mise, A.; Tamma, G.; Ranieri, M.; Svelto, M.; van den Heuvel, B.; Levtchenko, E.N.; Valenti, G. Conditionally Immortalized Human Proximal Tubular Epithelial Cells Isolated from the Urine of a Healthy Subject Express Functional Calcium-Sensing Receptor. Am. J. Physiol.-Ren. Physiol. 2015, 308, F1200–F1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mise, A.; Ranieri, M.; Centrone, M.; Venneri, M.; Tamma, G.; Valenti, D.; Valenti, G. Activation of the Calcium-Sensing Receptor Corrects the Impaired Mitochondrial Energy Status Observed in Renal Polycystin-1 Knockdown Cells Modeling Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2018, 5, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Mise, A.; Tamma, G.; Ranieri, M.; Centrone, M.; van den Heuvel, L.; Mekahli, D.; Levtchenko, E.N.; Valenti, G. Activation of Calcium-Sensing Receptor Increases Intracellular Calcium and Decreases cAMP and mTOR in PKD1 Deficient Cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söderberg, O.; Gullberg, M.; Jarvius, M.; Ridderstråle, K.; Leuchowius, K.-J.; Jarvius, J.; Wester, K.; Hydbring, P.; Bahram, F.; Larsson, L.-G.; et al. Direct Observation of Individual Endogenous Protein Complexes in Situ by Proximity Ligation. Nat. Methods 2006, 3, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredriksson, S.; Gullberg, M.; Jarvius, J.; Olsson, C.; Pietras, K.; Gústafsdóttir, S.M.; Ostman, A.; Landegren, U. Protein Detection Using Proximity-Dependent DNA Ligation Assays. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002, 20, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Perrett, S.; Kim, K.; Ibarra, C.; Damiano, A.E.; Zotta, E.; Batelli, M.; Harris, P.C.; Reisin, I.L.; Arnaout, M.A.; Cantiello, H.F. Polycystin-2, the Protein Mutated in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD), Is a Ca2+-Permeable Nonselective Cation Channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 1182–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.-F.; Sun, M.-M.; Hu, X.-Y.; Du, J.; He, W. TRPP2 Ion Channels: The Roles in Various Subcellular Locations. Biochimie 2022, 201, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yottasan, P.; Chu, T.; Chhetri, P.D.; Cil, O. Repurposing Calcium-Sensing Receptor Activator Drug Cinacalcet for ADPKD Treatment. Transl. Res. 2024, 265, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, S.; Nishide, K.; Okuno, S.; Ishimura, E.; Kabata, D.; Morioka, F.; Machiba, Y.; Uedono, H.; Tsuda, A.; Shoji, S.; et al. Cinacalcet May Suppress Kidney Enlargement in Hemodialysis Patients with Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmer, M.J.; Saleem, M.A.; Masereeuw, R.; Ni, L.; van der Velden, T.J.; Russel, F.G.; Mathieson, P.W.; Monnens, L.A.; van den Heuvel, L.P.; Levtchenko, E.N. Novel Conditionally Immortalized Human Proximal Tubule Cell Line Expressing Functional Influx and Efflux Transporters. Cell Tissue Res. 2010, 339, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekahli, D.; Sammels, E.; Luyten, T.; Welkenhuyzen, K.; van den Heuvel, L.P.; Levtchenko, E.N.; Gijsbers, R.; Bultynck, G.; Parys, J.B.; De Smedt, H.; et al. Polycystin-1 and Polycystin-2 Are Both Required to Amplify Inositol-Trisphosphate-Induced Ca2+ Release. Cell Calcium 2012, 51, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, J.; Schophuizen, C.M.S.; Wilmer, M.J.; Lahham, S.H.M.; Mutsaers, H.A.M.; Wetzels, J.F.M.; Bank, R.A.; van den Heuvel, L.P.; Hoenderop, J.G.; Masereeuw, R. A Morphological and Functional Comparison of Proximal Tubule Cell Lines Established from Human Urine and Kidney Tissue. Exp. Cell Res. 2014, 323, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamma, G.; Lasorsa, D.; Trimpert, C.; Ranieri, M.; Di Mise, A.; Mola, M.G.; Mastrofrancesco, L.; Devuyst, O.; Svelto, M.; Deen, P.M.T.; et al. A Protein Kinase A-Independent Pathway Controlling Aquaporin 2 Trafficking as a Possible Cause for the Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuresis Associated with Polycystic Kidney Disease 1 Haploinsufficiency. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2014, 25, 2241–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Zio, R.; Gerbino, A.; Forleo, C.; Pepe, M.; Milano, S.; Favale, S.; Procino, G.; Svelto, M.; Carmosino, M. Functional Study of a KCNH2 Mutant: Novel Insights on the Pathogenesis of the LQT2 Syndrome. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 6331–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranieri, M.; Venneri, M.; Pellegrino, T.; Centrone, M.; Di Mise, A.; Cotecchia, S.; Tamma, G.; Valenti, G. The Vasopressin Receptor 2 Mutant R137L Linked to the Nephrogenic Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuresis (NSIAD) Signals through an Alternative Pathway That Increases AQP2 Membrane Targeting Independently of S256 Phosphorylation. Cells 2020, 9, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerbino, A.; Ranieri, M.; Lupo, S.; Caroppo, R.; Debellis, L.; Maiellaro, I.; Caratozzolo, M.F.; Lopez, F.; Colella, M. Ca2+-Dependent K+ Efflux Regulates Deoxycholate-Induced Apoptosis of BHK-21 and Caco-2 Cells. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 955–964.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Mise, A.; Ferrulli, A.; Centrone, M.; Venneri, M.; Ranieri, M.; Tamma, G.; Caroppo, R.; Valenti, G. Functional Coupling of Calcium-Sensing Receptor and Polycystin-2 in Renal Epithelial Cells: Physiological Role and Potential Therapeutic Target in Polycystic Kidney Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 12004. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412004

Di Mise A, Ferrulli A, Centrone M, Venneri M, Ranieri M, Tamma G, Caroppo R, Valenti G. Functional Coupling of Calcium-Sensing Receptor and Polycystin-2 in Renal Epithelial Cells: Physiological Role and Potential Therapeutic Target in Polycystic Kidney Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):12004. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412004

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Mise, Annarita, Angela Ferrulli, Mariangela Centrone, Maria Venneri, Marianna Ranieri, Grazia Tamma, Rosa Caroppo, and Giovanna Valenti. 2025. "Functional Coupling of Calcium-Sensing Receptor and Polycystin-2 in Renal Epithelial Cells: Physiological Role and Potential Therapeutic Target in Polycystic Kidney Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 12004. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412004

APA StyleDi Mise, A., Ferrulli, A., Centrone, M., Venneri, M., Ranieri, M., Tamma, G., Caroppo, R., & Valenti, G. (2025). Functional Coupling of Calcium-Sensing Receptor and Polycystin-2 in Renal Epithelial Cells: Physiological Role and Potential Therapeutic Target in Polycystic Kidney Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 12004. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262412004